Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:09

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Cultural Effects on Business Students’ Ethical

Decisions: A Chinese Versus American Comparison

Sherry F. Li & Obeua S. Persons

To cite this article: Sherry F. Li & Obeua S. Persons (2011) Cultural Effects on Business Students’ Ethical Decisions: A Chinese Versus American Comparison, Journal of Education for Business, 86:1, 10-16, DOI: 10.1080/08832321003663330

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832321003663330

Published online: 20 Oct 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 193

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832321003663330

Cultural Effects on Business Students’ Ethical

Decisions: A Chinese Versus American Comparison

Sherry F. Li and Obeua S. Persons

Rider University, Lawrenceville, New Jersey, USA

The authors used a corporate code of ethics to create 18 scenarios for examining cultural effects on ethical decisions of Chinese versus American business students. Four cultural differences were hypothesized to contribute to overall less ethical decisions of Chinese students. The results support the hypothesis and indicate strong cultural effects on 5 areas of the code: (a) accurate accounting records, (b) proper use of company assets, (c) compliance with laws, (d) trading on inside information, and (e) reporting unethical behavior. Business educators and corporate ethics trainers should be aware of these cultural effects, and provide more coverage and special emphasis on these areas when they have Chinese students or entry-level personnel.

Keywords: Chinese, code of ethics, cultural differences, cultural effects, ethical decisions

In recent years, a growing body of research has been dedi-cated to documenting and understanding the effects of cul-tural differences on ethical decision making (e.g., Ahmed, Chung & Eichenseher, 2003; Ge & Thomas, 2008; Hoivik, 2007; Phau & Kea, 2007). Among these cross-cultural stud-ies, China not surprisingly has received considerable atten-tion, as it is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Since the 1978 economic reform, which led to the transition from the centrally planned economy to the market-oriented economy, China has taken many steps to attract foreign investments. However, practitioners, researchers, and regulators have consistently expressed a great deal of concern on the issue of business ethics in China, which does not seem to keep pace with the development of its market-oriented economy.

In the United States, the recent financial crises and busi-ness scandals such as the Enron, WorldCom, and Madoff fraud have also made business ethics a highly important issue to both the academia and the investment community. To pre-vent financial malpractices and encourage ethical business conduct, in 2002 the U.S. Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which is considered to be the most far-reaching securities law in the past decades. Section 406 of the Act

Correspondence should be addressed to Sherry F. Li, Rider Univer-sity, Accounting Department, 2083 Lawrenceville Road, Lawrenceville, NJ 08648, USA. E-mail: fanli@rider.edu

requires both U.S. and foreign listed companies to disclose their code of ethics.1

In the present study we used a real-world corporate code of ethics as a roadmap to create 18 scenarios for exam-ining cultural effects on the ethical decisions of Chinese and American business students. Such examination pro-vides business-setting evidence consistent with Hofstede and Hofstede (2005)’s finding that the Chinese businesses sub-stantially differ from American businesses in certain cultural dimensions. This cross-cultural comparison of ethical de-cision making is important because the Chinese economy is becoming tightly integrated into the global economy and relies on Western capital, technology, and demand. Such re-liance is likely to push Chinese firms to adopt Western or-ganizational patterns and conform to Western ways of doing business. As a result, although the Chinese government has not required Chinese public companies to adopt or disclose a code of ethics, and not all Chinese companies have vol-untarily adopted an ethics code, the aforementioned reasons, such as demand for more foreign capital, would eventually motivate Chinese companies to adopt a code similar to that of U.S. companies. Foreign investors would likely perceive such adoption as a positive signal of the company’s commitment to ethical business conduct, which could help lower its cost of capital and enhance its ability to attract foreign capital. No prior studies (e.g., Hoivik, 2007; Phau & Kea, 2007; Shafer, Fukukawa, & Lee, 2007) examining the cultural effects on ethical decision making have used a real-world corporate code of ethics for developing questions or scenarios.

CULTURAL EFFECTS ON STUDENTS’ ETHICAL DECISIONS 11

A logit regression analysis shows that cultural differences seem to contribute to less ethical decisions of Chinese stu-dents compared to American stustu-dents across all 18 scenarios combined. An additional analysis indicates strong cultural effects on five areas of an ethics code: (a) accurate account-ing records, (b) proper use of company assets, (c) compliance with laws, (d) trading on inside information, and (e) reporting unethical behavior. We acknowledge that these 18 ethics sce-narios inherently reflect Western cultural values, and there-fore American students may have an advantage in identifying the correct ethical choices relative to their Chinese coun-terparts. However, the Chinese students in this study were global business majors who had taken core business courses taught by American professors as a curriculum requirement. Consequently, they were likely aware of the Chinese com-panies’ globalization efforts as well as the Western business practices and cultural values. Moreover, at the time of study, the majority of the Chinese participants had already been accepted into or were applying for a business program at a university in the United States or had indicated desires to pursue a graduate degree in Western countries. There-fore, this sample likely resembles Chinese students studying in the United States. This means that the findings of this study could have an important implication not only for U.S. business schools that have operations in China but also for business educators in the United States and corporate ethics trainers of U.S. firms that provide internships for Chinese students. In particular, they should be aware of the cultural differences, and adjust their ethics course-coverage or train-ing programs to emphasize the code-of-ethics areas signifi-cantly affected by culture when they have Chinese students, interns or entry-level personnel. This is especially important as many U.S. higher education institutions have recruited and admitted more international students especially the Chinese.

Corporate Code of Ethics and Questionnaire Development

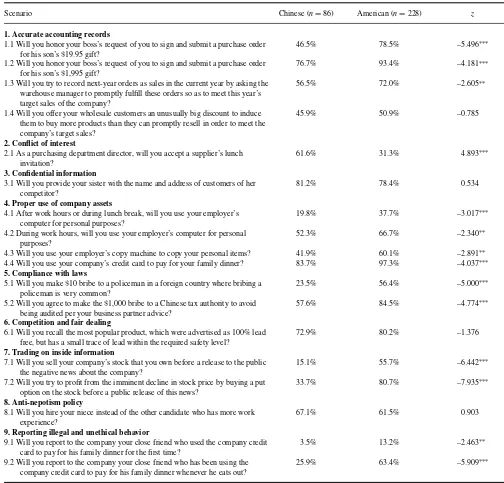

A corporate code of ethics typically covers nine common areas. These nine areas together with their description came from a real-world company’s code of ethics.2 Short ethics

scenario(s), each with a question requiring a yes or a no answer, is (are) presented under each area of the code in Table 1. A yes–no methodology is used because from a cor-porate viewpoint an employee’s conduct is either in com-pliance with the code (being ethical) or in violation of the code (being unethical). These scenarios are based on counting issues discussed in textbooks, suggested by ac-counting alumni who are certified public accountants or cer-tified internal auditors, or adapted from real-world articles published in business periodicals. An Accounting Depart-ment’s Advisory Board members, who were corporate exec-utives or partners of public accounting firms, reviewed these

scenarios, and their comments were incorporated into the questionnaire.

1. Accurate accounting records: All business records must be clear, truthful and accurate. This includes such data as quality, safety, personnel, and all financial records. Misrepresenting facts or falsifying company records is a serious offense.

2. Conflict of interest: Employees must make business decisions and actions based on the best interests of the company and its stakeholders, and must not be motivated by personal considerations or relationships. For example, relationships with prospective or exist-ing suppliers, contractors, customers, competitors, or regulators must not affect employees’ independent and sound judgment.

3. Confidential information: Except in connection with the performance of their duties, employees are prohib-ited from disclosing or using confidential or proprietary information outside the company, either during or after employment, without company authorization. 4. Proper use of company assets: Protecting company

assets against loss, theft, and misuse is every em-ployee’s responsibility. The company’s equipment, ve-hicles, tools, and supplies are to be used for conducting company business. They may not be used for personal benefit.

5. Compliance with laws: Employees must comply with laws and regulations wherever company does business. Foreign Corrupt Practice Act prohibits U.S. firms and their workers or agents from bribing foreign officials. 6. Competition and fair dealing: Employees must not use

any illegal or unethical methods to gather competi-tive information. The Federal Trade Commission Act prohibits misrepresentations of all sorts that are made in connection with sales including false or misleading advertisement.

7. Trading on inside information: Using inside material information, which is not available to the public, for trading or tipping others to trade is both unethical and illegal.

8. Anti-nepotism policy: To reduce favoritism or the ap-pearance of favoritism and to prevent family conflict from affecting the workplace, an employee’s relative is not permitted to work as a supervisor or a subordinate of the employee.

9. Reporting illegal and unethical behavior: Employees have a duty to promptly report violations of a corporate code of ethics via an anonymous phone hotline or to an appropriate company representative (e.g., Chief Com-pliance Officer or Chairman of an Audit Committee). In addition, a company usually requires employees to certify that they have complied with all areas of the code.

TABLE 1

Percentage of Students’ Ethical Responses to the 18 Scenarios Under the Nine Common Areas of a Corporate Code of Ethics

Scenario Chinese (n=86) American (n=228) z

1. Accurate accounting records

1.1 Will you honor your boss’s request of you to sign and submit a purchase order for his son’s$19.95 gift?

46.5% 78.5% –5.496∗∗∗

1.2 Will you honor your boss’s request of you to sign and submit a purchase order for his son’s$1,995 gift?

76.7% 93.4% –4.181∗∗∗

1.3 Will you try to record next-year orders as sales in the current year by asking the warehouse manager to promptly fulfill these orders so as to meet this year’s target sales of the company?

56.5% 72.0% –2.605∗∗

1.4 Will you offer your wholesale customers an unusually big discount to induce them to buy more products than they can promptly resell in order to meet the company’s target sales?

45.9% 50.9% –0.785

2. Conflict of interest

2.1 As a purchasing department director, will you accept a supplier’s lunch invitation?

61.6% 31.3% 4.893∗∗∗

3. Confidential information

3.1 Will you provide your sister with the name and address of customers of her competitor?

81.2% 78.4% 0.534

4. Proper use of company assets

4.1 After work hours or during lunch break, will you use your employer’s computer for personal purposes?

19.8% 37.7% –3.017∗∗∗

4.2 During work hours, will you use your employer’s computer for personal purposes?

52.3% 66.7% –2.340∗∗

4.3 Will you use your employer’s copy machine to copy your personal items? 41.9% 60.1% –2.891∗∗

4.4 Will you use your company’s credit card to pay for your family dinner? 83.7% 97.3% –4.037∗∗∗

5. Compliance with laws

5.1 Will you make$10 bribe to a policeman in a foreign country where bribing a policeman is very common?

23.5% 56.4% –5.000∗∗∗

5.2 Will you agree to make the$1,000 bribe to a Chinese tax authority to avoid being audited per your business partner advice?

57.6% 84.5% –4.774∗∗∗

6. Competition and fair dealing

6.1 Will you recall the most popular product, which were advertised as 100% lead free, but has a small trace of lead within the required safety level?

72.9% 80.2% –1.376

7. Trading on inside information

7.1 Will you sell your company’s stock that you own before a release to the public the negative news about the company?

15.1% 55.7% –6.442∗∗∗

7.2 Will you try to profit from the imminent decline in stock price by buying a put option on the stock before a public release of this news?

33.7% 80.7% –7.935∗∗∗

8. Anti-nepotism policy

8.1 Will you hire your niece instead of the other candidate who has more work experience?

67.1% 61.5% 0.903

9. Reporting illegal and unethical behavior

9.1 Will you report to the company your close friend who used the company credit card to pay for his family dinner for the first time?

3.5% 13.2% –2.463∗∗

9.2 Will you report to the company your close friend who has been using the company credit card to pay for his family dinner whenever he eats out?

25.9% 63.4% –5.909∗∗∗

Note.A “no” answer was deemed ethical for all scenarios except for 6.1, 9.1, and 9.2, where a “yes” answer was ethical.

∗p<.05.∗∗p<.01.∗∗∗p<.001.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

As suggested by many previous cross-cultural studies (e.g., Hofstede, 2006; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005; Hung, 2008; Rothlin, 2008; Shafer et al., 2007; Tam, 2002), four cultural dimensions are expected to affect students’ ethical decisions: (a) power distance, (b) individualism versus collectivism, (c) difference in socioeconomic values, and (d) rule of men versus rule of law. The effect of each dimension on students’

ethical decision making in specific scenarios is discussed subsequently.

Small power distance versus large power distance.

Power distance measures “the extent to which the less power-ful members of institutions and organizations within a coun-try expect and accept that power is distributed unequally” (Hofstede, 1991, p. 28). In small power distance societies,

CULTURAL EFFECTS ON STUDENTS’ ETHICAL DECISIONS 13

organizations are fairly decentralized. Superiors treat subor-dinates as equals and tend to consult them before making a work-related decision. Employees are usually not afraid of confronting their bosses when disagreement arises. In large power distance countries, more powerful people are supposed to be privileged and respected. Organizations are rather centralized. Subordinates are more tolerant of hier-archy and inequality, less likely to question and challenge authority, and tend to act in their superiors’ interest when disagreement arises (Ge & Thomas, 2008; Hofstede, 2006; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

English-speaking Western countries are generally con-sidered to have small power distance whereas Asian coun-tries typically have large power distance. Hofstede and Hofstede (2005) reported that the United States scored 40 on the Power Distance Index, much lower than the world av-erage of 60 and China’s score of 80.3Cohen, Pant, and Sharp (1993) suggested that the unwillingness to accept power and inequality in small power distance countries, such as the United States, may prevent subordinates’ obedience to supe-riors when told to conduct unethical behaviors. This cultural dimension likely contributes to less ethical responses among Chinese students in scenarios involving superior-subordinate relationship, specifically, Scenarios 1.1 and 1.2 in Table 1.

Individualism versus collectivism. Individualism, as opposed to collectivism, describes the degree to which in-dividuals are integrated into groups. In individualistic soci-eties, people are bonded loosely with others and tend to think and judge in terms ofIinstead of we. Individual goals and achievement are valued. In business, recruiting and promo-tion decisions are supposed to be solely based on capabil-ity and skills (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). Nepotism and discrimination in favor of friends or in-group members are discouraged and prohibited. On the other hand, the collective cultures greatly emphasize the ties with in-group members.

Weis more important thanI. People should share resources with relatives and friends and be loyal to the social groups that they belong to (Ge & Thomas, 2008; Hofstede & Hofstede; Shafer et al., 2007; Tsui & Windsor, 2001). At workplaces, employees are expected to give priority to organizational goals and interests (Hofstede & Hofstede; Hofstede, 2006). In general, Western cultures are considered to be highly in-dividualistic whereas Eastern societies are more collective. The United States has an individualism score of 91, ranking as No. 1 among all the 74 countries and regions, whereas China’s score is 20, which is far below the world average of 44 and the United States’ score.

Research has shown that the individualism dimension has a strong influence on people’s ethical value (Cohen et al., 1993; Ge & Thomas, 2008; Shafer et al., 2007). Addition-ally, Dunfee and Warren (2001) and Woodbine (2004) sug-gested that some features of collective Chinese culture such as guanxi, which creates obligations for the continued ex-change of favors, could foster unethical business practices

such as corruption and bribery. This cultural dimension likely contributes to less ethical decisions among Chinese students in Scenarios 1.3 and 1.4 (meeting corporate goals), 2.1 (con-flict of interest), 3.1 (relationship with family member), 5.1 and 5.2 (bribery), 8.1 (nepotism), and 9.1 and 9.2 (reporting unethical behaviors of close friend).

Difference in socioeconomic values. Before the 1978 economic reform, the Chinese government had direct control over all resources regarding how they are distributed and used. People lived in commune-like organizations where everybody had an iron rice bowl and enjoyed cradle-to-grave welfare. In such organizations, there was no concept of privately owned assets because all assets were collectively owned and used by its members. Although the privatization since 1978 has greatly improved the decision-making effi-ciency, it has also resulted in management corruption due to the socioeconomic value of no clear distinction between organizational and private assets, and the lack of monitor-ing mechanisms. Hung (2008) stated, “As many Chinese economists point out, the problem of management corrup-tion is tied to the way the assets of privatized enterprises can be transformed, through various means, into private assets” (p. 74).

Unlike China, the United States has never adopted a highly centralized economic system. Company assets are distinct and legally separated from personal assets under the U.S. market-oriented economy. U.S. companies have established a code of ethics and an internal control to protect company assets from personal use. Even though Chinese student par-ticipants in this study were born after 1978, it is plausible that they may have inherited from their parents the socioeco-nomic value of no clear distinction between organizational and private assets. This difference can potentially affect sce-narios about the proper use of company assets (Scesce-narios 4.1–4) in a way that it leads to less ethical answers among Chinese students.

Rule of men versus rule of law. Hundreds of years of Confucian heritage has established China as a country ruled by men instead of laws because Confucius and his follow-ers trust and rely on innate human goodness for governance rather than written laws that are too inflexible to handle var-ious human activities (Iqbal, 2002). Although in the past two decades the Chinese government has tried to establish a fair legal system, the public awareness of law is still weaker than in the Western countries where the rule of law is firmly rooted. Although China has laws in many areas against un-desirable business conduct, the enforcement mechanisms are not strong enough to deter such conduct. For example, the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission can only sug-gest the companies to remove illegal insider traders from their positions, usually only profitable insiders are charged with a monetary penalty and an imprisonment term of up to 5 years (Shen, 2007).

Many researchers have expressed considerable concerns that the weak legal environment in China would lead to unethical and irresponsible business practices (e.g., Shafer et al. 2007; Tam, 2002). Rothlin (2008) noted that,

More than in any other circumstances, business people op-erating in China seem to move on a lawless ground where corruption and nepotism, as well as all kinds of fraud and abuses seem to be unavoidable in order to obtain the desired business success, deeply rooted in a culture where relation-ships take precedence over any ethical consideration and law. (p. 8)

This cultural dimension likely contributes to less ethical responses by Chinese students in Scenarios 6.1 (product re-call) and 7.1 and 7.2 (insider trading).

In sum, the discussions above suggest less ethical deci-sions of Chinese students compared to their American peers across all 18 scenarios. This leads to the hypothesis that cultural differences likely contribute to overall less ethical decisions of Chinese students.

METHOD

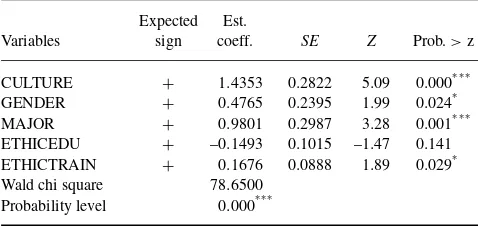

The hypothesis was tested by using the following ordered-logit regression model with five explanatory variables, one of which is culture, with the others being control variables.

ETHIC=a+b1CULTURE+b2GENDER+b3MAJOR+

b4ETHICEDU+b5ETHICTRAIN

ETHIC=Total number of ethical responses of each student to the 18 scenarios

CULTURE=1 for an American student (born and raised in the United States), and 0 for a Chinese student (born and raised in China)

GENDER=1 for female participant and 0 for male partici-pant

MAJOR=1 for an accounting major and 0 otherwise ETHICEDU=Number of college-level ethics courses taken ETHICTRAIN=Number of workplace ethics training

The hypothesis was supported if the coefficient of CUL-TURE was significantly positive. The other four control vari-ables were also expected to have a positive coefficient. Re-garding GENDER, prior studies (e.g., Albaum & Peterson, 2006; Cohen, Pant, & Sharp, 1998; Libby & Agnello, 2000) found that female students are more ethical than male dents. This gender difference is also documented among stu-dents in foreign countries (Roxas & Stoneback, 2004). With respect to MAJOR, Cohen et al. and Manley, Russell, and Buckley (2001) suggested that accounting majors may be more ethical than other business majors because the public and the regulators, such as the SEC, demand that the ac-counting profession abides by rules and standards. Arlow and Ulrich (1983) attributed the higher ethicality of account-ing majors to the fact that accountaccount-ing majors receive

addi-tional training in accounting ethics within the accounting cur-riculum. Regarding ETHICEDU, the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business has suggested that ethics be taught in business schools because ethics education can have a positive influence on students’ ethicality as documented by Luthar, DiBattista, and Gautschi (1997) and Steven, Harris, and Willianson (1993). With respect to ETHICTRAIN, Beu, Buckley, and Harvey (2003) stated that training could be used to increase cognitive moral development and decrease inappropriate competitive desire to win at any cost. Results from a large-scale survey by Delaney and Sockell (1992) suggest that workplace ethics training has a positive effect on managers because the training educates managers on how to react when confronted with workplace dilemmas.

The American participants in this study were undergradu-ate business students from a privundergradu-ate Mid-Atlantic university with which the authors were affiliated. The Chinese par-ticipants were undergraduate business students from a pri-vate university in Shanghai, which has been in educational partnership with the authors’ university for several years. Business students were the focus because they soon would enter the business world and collectively constitute the fu-ture corporate leaders who will regularly face a number of ethical dilemmas. The participants completed scenario ques-tionnaires anonymously. There were a total of 314 stu-dent participants: 86 (27.4%) Chinese participants and 228 (72.6%) American participants.4The differential sample size

of Chinese and American participants reflects a difference in the raw number of students to whom the questionnaire was administered. A total of 64 (74.4%) of the 86 Chinese students women, whereas 94 (41.2%) of the 228 American students were women. No Chinese student was an accounting major, whereas 54 American students (23.7%) were account-ing majors. A total of 62 Chinese students (72.1%) versus 87 American students (38.2%) had at least one college-level ethics course. Fourteen Chinese students (16.3%) versus 95 American students (41.7%) had at least one workplace ethics training.

RESULTS

Table 2 reports regression results of the cultural effects on stu-dents’ overall ethical decisions, ETHIC, which for Chinese students had a minimum value of 3, a mean value of 8.63, and a maximum value of 13 out of 18 (SD=2.51). On the other hand, ETHIC for American students had a minimum value of 4, a mean value of 11.93, and a maximum value of 18 out of 18 (SD=3.41). The univariate Wilcoxon signed-rank test with a sizable zstatistic of –7.1 clearly indicated that, overall, Chinese students were significantly less ethical than American students. The logit regression analysis in Ta-ble 2, which controls for four variaTa-bles, also confirmed this univariate result. In particular, the results in Table 2 suggest that although three control variables, MAJOR, GENDER, and ETHICTRAIN, were significantly positive, CULTURE

CULTURAL EFFECTS ON STUDENTS’ ETHICAL DECISIONS 15

TABLE 2

Ordered-Logit Regression Results of the Five Explanatory Variables on the Chinese and American

Students’ Overall Ethical Decisions (ETHIC)

Variables

Wald chi square 78.6500

Probability level 0.000∗ ∗ ∗

Note.There were 314 student participants. ETHIC represents a total number of ethical responses of each student to the 18 scenarios. For CUL-TURE, 1=born in the United States or came to the United States before 10 years of age, and 0 otherwise. For GENDER, 1=women and 0=men. For MAJOR, 1=an accounting major and 0 otherwise. ETHICEDU represents the number of college-level ethics courses taken. ETHICTRAIN represents the number of workplace ethics training.

∗p<.05.∗∗∗p<.001.

had the most positive and most significant coefficient. These results strongly support the hypothesis that cultural differ-ences contribute to overall less ethical decisions of Chinese students.5

To provide further insight into the regression results, Table 1 presents percentage of students’ ethical responses to each of the 18 scenarios grouped by the nine common areas of a corporate code of ethics. Results indicate that Chinese stu-dents made significantly fewer ethical decisions than Ameri-can students in 13 scenarios related to five areas of an ethics code. These five areas were (a) accurate accounting records, (b) proper use of company assets, (c) compliance with laws, (d) trading on inside information, and (e) reporting unethical behavior. For the first area, accurate accounting records, Chi-nese students were more likely to (a) honor a boss’s request to sign and submit a purchase order for his son’s gift regard-less of a trivial or a substantial gift value, and (b) record sales in the present year by asking the warehouse manager to promptly fulfill next-year orders to meet this year’s target sales. The results are consistent with the small versus large power distance and the individualism versus collectivism ar-guments.

For the second area, proper use of company assets, Chi-nese students were more likely to use an employer’s com-puter, copy machine, and credit card for personal purposes. Although only 16.3% (14) Chinese students (vs. 2.7% [6] American students) would use a company’s credit card to pay for family dinner, educators and business ethics trainers should emphasize that such conduct is an outright stealing of a company’s fund, which is not only unethical but also illegal. This result is consistent with the argument regarding the difference in socioeconomic values between the Chinese and the American participants.

For the third significant area, compliance with laws, Chi-nese students were much more likely to make bribe to a po-liceman and to a tax authority than American students. The results support the individualism versus collectivism argu-ment and theguanxiculture. The weaker law enforcement in China relative to the United States may also explain these re-sults. For the fourth area, trading on inside information, 85% of Chinese students versus 44% of American students would sell the company’s stock that they own before a public release of the negative news, and 66% of Chinese students versus only 19% of American students would try to profit from the inside information. These results are consistent with the rule of men versus rule of law argument. The high percentage of unethical responses among Chinese students suggests that educators and corporate ethics trainers should greatly em-phasize to these students that trading on inside information is not only unethical but also illegal, and the insider trading law is strongly enforced in the United States.

For the fifth significant area, reporting illegal and un-ethical behavior, Chinese students were much less likely to report a close friend who uses the company credit card to pay for family dinner. This result is in line with the individual-ism versus collectivindividual-ism and theguanxiarguments. Educators and corporate ethics trainers should be particularly concerned that only 25.9% of Chinese students versus 63.4% of Ameri-can students would report the friend who misuses a company credit card all the time.

DISCUSSION

We used a real-world corporate code of ethics as a roadmap to create 18 scenarios for assessing cultural effects on the ethical decisions of Chinese versus American business stu-dents. We hypothesized that, overall, Chinese students would be more likely to make less ethical decisions than their Amer-ican peers due to the differences in four cultural dimensions: (a) small versus large power distance, (b) individualism ver-sus collectivism, (c) difference in socioeconomic values, and (d) rule of men versus rule of law. The logit regression re-sults strongly support the hypothesis, and indicate significant cultural effects on five areas of an ethics code: (a) accurate accounting records, (b) proper use of company assets, (c) compliance with laws, (d) trading on inside information, and (e) reporting unethical behavior. These findings suggest that business educators and corporate ethics trainers should in-crease coverage and place a greater emphasis on these areas of the code when they have Chinese students or entry-level personnel in their classes so as to make them aware of po-tentially negative consequences of unethical behavior.

A limitation of this study is that it did not have a large sample, and the participants were from only one university in the United States and one university in China. Such a limitation might have affected the generalizability of the re-sults. However, the study serves as a starting point for future researchers, who may want to use a corporate code of ethics to

further explore cultural effects on an individual’s ethical deci-sions. Future researchers should include a direct examination of the relationships between the students’ ethical decisions and the four cultural variables, as the associations indicated by the present study may be speculative and indirect. Other interesting areas for future researchers could be exploring the stability or persistence of cultural values by comparing the ethical decisions made by Chinese students, Chinese Amer-ican students, and non-Chinese AmerAmer-ican students all in the United States, or to examine a different culture other than Chinese culture.

NOTES

1. A publicly traded company may disclose the code in its annual report, on its website, or state that the code is available upon request. A company that has not adopted the code of ethics is required to provide an explanation.

2. These areas are in accordance with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the NYSE and the NASDAQ ethics requirements.

3. The world average for each Hofstede cultural dimen-sion is calculated by this study as the mean score of the 74 countries and regions reported in Hofstede and Hofstede (2005).

4. At the time the surveys were filled out, 30 out of the 86 Chinese students had accepted the offer to continue their undergraduate study at the authors’ university, and came to the United States a few months later. One student had ac-cepted a similar offer from another university in the United States. More than 10 students were in the process of ap-plying for graduate programs in the United States and other Western countries. The majority of the rest of the students indicated that they had planned to pursue an advanced degree in Western countries after graduation.

5. To explore whether the differential sample sizes (86 Chinese participants vs. 228 American participants) affected the study results, we randomly selected 86 out of the 228 American participants and repeated the logit regression anal-ysis. Results based on the same sample size of 86 American and 86 Chinese students also strongly supported the hypoth-esis (i.e., CULTURE had azstatistic of 4.91 and Prob.>z was .000).

REFERENCES

Ahmed, M. M., Chung, K. Y., & Eichenseher, J. W. (2003). Business stu-dents’ perception of ethics and moral judgment: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Business Ethics,43(1/2), 89–102.

Albaum, G., & Peterson, R. A. (2006). Ethical attitudes of future business leaders: Do they vary by gender and religiosity?Business and Society, 45, 300–321.

Arlow, P., & Ulrich, T. A. (1983). Can ethics be taught to business students? College Forum,14(Spring), 17.

Beu, D. S., Buckley, M. R., & Harvey, M. G. (2003). Ethical decision-making: A multidimensional construct.Business Ethics: A European Re-view,12, 88–107.

Cohen, J. R., Pant, L. W., & Sharp, D. J. (1993). Culture-based ethical con-flicts confronting multinational accounting firms.Accounting Horizons, 7(3), 1–13.

Cohen, J. R., Pant, L. W., & Sharp, D. J. (1998). The effect of gender and academic discipline diversity on the ethical evaluations, ethical intentions and ethical orientation of potential public accounting recruits.Accounting Horizons,12, 250–270.

Delaney, J. T., & Sockell, D. (1992). Do company ethics training program make a difference? An empirical analysis.Journal of Business Ethics,11, 719–727.

Dunfee, T. W., & Warren, D. E. (2001). Is guanxi ethical? A normative anal-ysis of doing business in China.Journal of Business Ethics,32, 191–204. Ge, L., & Thomas, S. (2008). A cross-cultural comparison of the delibera-tive reasoning of Canadian and Chinese accounting students.Journal of Business Ethics,82, 189–211.

Hofstede, G. (1991).Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2006). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context.Online readings in psychology and culture, unit 2: Conceptual, methodological and ethical issues in psychology and culture. Bellingham, WA: Center for Cross-Cultural Research, Western Washington University. Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005).Cultures and organizations: Software

of the mind. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hoivik, H. (2007). East meets west: Tacit messages about business ethics in stories told by Chinese managers.Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 457–469.

Hung, H. (2008). Normalized collective corruption in a transitional econ-omy: Small treasuries in large Chinese enterprises.Journal of Business Ethics,79(1–2), 69–83.

Iqbal, M. Z. (2002).International accounting: A global perspective. Cincin-nati, OH: South-Western.

Libby, B., & Agnello, V. (2000). Ethical decision making and the law. Journal of Business Ethics,26, 223–232.

Luthar, H., DiBattista, R., & Gautschi, T. (1997). Perception of what ethical climate is and what it should be.Journal of Business Ethics,16, 205–217. Manley, G., Russell, C., & Buckley, M. R. (2001). Self-enhancement in perception of unethical behavior.Journal of Education for Business,77, 21–28.

Phau, I., & Kea, G. (2007). Attitudes of university students toward business ethics: A cross-national investigation of Australia, Singapore and Hong Kong.Journal of Business Ethics,72, 61–75.

Rothlin, S. (2008). The chance of international business ethics in the Chinese context.Chinese Cross Currents,5(1), 8–17.

Roxas, M. L., & Stoneback, J. Y. (2004). The importance of gender across cultures in ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 50, 149–165.

Shafer, W., Fukukawa, K., & Lee, G. (2007). Values and the perceived importance of ethics and social responsibility: The U.S. versus China. Journal of Business Ethics,70, 265–284.

Shen, H. (2007).A comparative study of enforcement of insider trading regu-lation between the U.S. and China. Working paper, New York University, New York, NY.

Steven, R., Harris, O., & Williamson, S. (1993). A comparison of ethical evaluations of business school faculty and students: A pilot study.Journal of Business Ethics,12, 611–619.

Tam, O. K. (2002). Ethical issues in the evolution of corporate governance in China.Journal of Business Ethics,37, 303–320.

Tsui, J., & Windsor, C. (2001). Some cross-cultural evidence on ethical reasoning.Journal of Business Ethics,31, 143–150.

Woodbine, G. F. (2004). Moral choice and the declining influence of tradi-tional value orientations within the financial sector of a rapidly developing region of the People’s Republic of China.Journal of Business Ethics,55, 43–60.