Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI

TANJUNGPINANG, KEPULAUAN RIAU] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:55

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Active Versus Passive Course Designs: The Impact

on Student Outcomes

Sue Stewart Wingfield & Gregory S. Black

To cite this article: Sue Stewart Wingfield & Gregory S. Black (2005) Active Versus Passive Course Designs: The Impact on Student Outcomes, Journal of Education for Business, 81:2, 119-123, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.2.119-128

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.2.119-128

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 131

View related articles

ABSTRACT. The objective of this

study was to investigate the impact of

course design on both actual and

self-reported student outcomes. The authors

examined data gathered from three courses,

each with a different design, during one

semester at a major university in the

South-west. One passive design was used and was

patterned after the traditional method of

lecture, notetaking, and multiple-choice

exams. Two active designs were used. One

active design was a participative course

where students helped plan the course by

developing the syllabus and deciding what

criteria should be graded. The other active

design was experiential in nature where

stu-dents were exposed to assignments and

activities designed to simulate real-world

tasks and experiences. Results indicated

that students perceived active course

designs to be more useful to their future

than passive designs. However, course

design appeared to have no impact on

stu-dent grades, satisfaction, or perceptions of

how a course was conducted.

Copyright © 2005 Heldref Publications

The Impact of Teaching

Today’s changing environment requires employees who can analyze and synthe-size information from multiple sources, make a decision, and implement a course of action. These employees must possess strong communication skills; be flexible, yet decisive; and be prepared to apply knowledge in diverse situations. Therefore, business schools today must accept the responsibility for providing students with these necessary skills. Faculty must concern themselves with a dual purpose: (a) imparting knowledge and (b) developing the skills required in today’s dynamic business environment. As a result, identifying characteristics or styles of education that can have the greatest and most permanent impact on business students is becoming an increasingly crucial issue. This leads to a key question: Are we, as faculty, employing teaching styles that have a positive impact on student learning and thereby creating desirable employees?

Methods of Instruction

A review of the existing literature on teaching styles indicates that a clear dis-tinction exists between active and pas-sive types of teaching styles. Active course design, in all its forms, incorpo-rates increased student involvement in the classroom, whereas passive designs are more instructor-centered. Active

course designs are based on the assump-tion that an active learner, or one who is more engaged in the learning process, learns much more effectively and the learning experience is more intense and permanent than for passive learners enrolled in a traditional lecture-style class (Labinowicz, 1980).

Experiential learning is a type of active course design. It can be defined as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (Kolb, 1984, p. 38). Kolb indicates that the crucial first step in experiential learning is to provide the experience from which the learning comes. Experiential educators are gen-erally aware that experiences alone are not inherently good for learning. The experiences have to be relevant to the learning goals and then the learners must have time and opportunity to reflect on the experience. Kolb’s defini-tion is based on six assumpdefini-tions: “Learning (a) is a process, not an out-come; (b) derives from experience; (c) requires an individual to resolve dialec-tically opposed demands; (d) is holistic and integrative; (e) requires interplay between a person and the environment; and (f) results in knowledge creation” (Kayes, 2002, pp. 139–140). These assumptions intimate that learners will be required to respond “to diverse per-sonal and environmental demands that arise from the interaction between

expe-Active Versus Passive Course Designs:

The Impact on Student Outcomes

SUE STEWART WINGFIELD GREGORY S. BLACK

TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY–CORPUS CHRISTI CORPUS CHRISTI, TEXAS

rience, concept, reflection, and action in a cyclical … fashion” (Kayes, p.140).

Keeping these assumptions in mind, experiential learning can encompass a wide array of methodologies spanning from outdoor, adventure-based learning, such as Outward Bound, to other forms that are more conducive to a classroom setting. Case studies are commonly used in many business classes. In addition, giving students self-learning instruments also provides them with experiential learning opportunities. Many universities offer business credit for internships and these internships are also effective expe-riential learning experiences. Also, many in-class activities are experiential in nature. In addition, assignments can be experiential if they require students to apply concepts learned in the classroom to things they will be expected to do in the “real world” after they graduate. For example, professors may require students to write a marketing plan, create an actu-al advertisement, or develop a perfor-mance appraisal system or a compensa-tion plan. Experiential methods rely heavily on discussion and practice, emphasizing personal application of material and encouraging students to develop belief systems, to understand how they feel about an area of study, and to take appropriate actions given a specif-ic environment (Jones & Jones, 1998).

Participative learning is also a form of active learning. It can be defined as engaging the learner in the learning process (Mills-Jones, 1999). Participa-tive learning has been confused with a similar term known as cooperative learning. Cooperative learning is a mode of learning that requires students to work together in groups and class dis-cussions. By contrast, participative learning gives students the opportunity to take an active part in determining the types of activities or assignments they perceive will best help their learning. Methods that can be used in the class-room to assure participative learning include the following: (a) student partic-ipation in the syllabus design, (b) stu-dents writing potential exam questions, and (c) student participation in the grad-ing scheme for the course. By involvgrad-ing students in these decisions, participative learning theory suggests that the stu-dents will feel more accountability for

completing assignments and for study-ing for exams (Mills-Jones).

Traditional lecture classes are a form of passive learning. Passive learning

emphasizes learning conceptual knowl-edge by focusing on facts and theoreti-cal principles (Jones & Jones, 1998; Thornton & Cleveland, 1990; Whetten & Clark, 1996). The conceptual empha-sis of this design can be important to development of a strong theoretical foundation upon which students can build in future courses. This design typ-ically involves few opportunities for students to learn experientially or to participate in the decisions in the class-room. Professors or instructors basical-ly provide a syllabus and class schedule, they deliver daily lectures, and the majority of grades are based on exams, especially exams made of multiple-choice, true-false, and matching items. See Appendix A for a summary of the three course designs and the types of classroom activities each employs.

Researchers have suggested that stu-dents learn more effectively when they are able to experience learning through active participation in the learning process (Allen & Young, 1997). Active learning has also been linked to critical thinking (Paul, 1990), experiential learning (Kolb, 1984), and reflective judgment (King & Kitchener, 1994; Kitchener & King, 1981), which are all important educational concepts (Allen & Young, 1997). Some researchers also have suggested that experiential learn-ing leads to higher levels of retention for student learning (e.g., Van Eynde & Spencer, 1988), whereas others have suggested that there are no significant differences exhibited by students on measures of comprehension or satisfac-tion when different teaching styles are used (Miner, Das, & Gale, 1984).

This mixed evidence leaves questions that are not yet fully answered. Is active learning more effective? Does it create the skilled managers for which employ-ers are looking? Unfortunately, no method has emerged as superior in all areas of student outcomes. Despite the mixed evidence, it is still generally accepted that active learning methods are more effective, but their use in business classes appears to be modest at best (Whetten, Windes, May, & Bookstaver,

1991). The use of active learning in the business classroom should be important in assessing the effectiveness of business classes in assuring the maximum impact of students’ education when they enter the business world. Our objective in this study was to investigate the impact of course design on both actual and self-reported student outcomes. We examined data gathered during one semester at a major university in the Southwest by pro-fessors who have used the three types of active and passive course design: (a) experiential, (b) participative, and (c) passive. Each design was used in one class during the semester.

Hypotheses

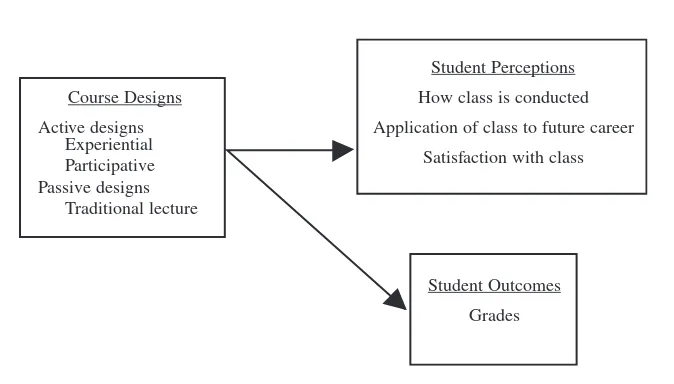

On the basis of the previous discus-sion, one might suppose that the active course designs, both participative and experiential, examined in this research would prove to be more effective than the traditional lecture design. In an effort to add support to this suggestion, we attempted to isolate the actual impact that three course designs have on student perceptions and outcomes. The dependent variables under investigation included the following: (a) students’ actual grades in the class, (b) students’ perceptions of how well the class was conducted, (c) students’ perceptions of how useful the learning they received in the course would be to their future careers, and (d) students’ satisfaction with the course. A general model of this study and the hypotheses examined are presented in Figure 1.

The primary emphasis of active course design, in all its forms, is an increased student involvement in the classroom, whereas passive designs are more instructor-centered. This inherent focus on the student should prove to be more effective in the classroom than the traditional, passive lecture style. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis.

H1: Active course designs will result in more positive student outcomes in grades, overall satisfaction with a course, student perceptions of how well a class was con-ducted, and student perceptions of the usefulness of a course to their future careers than passive course designs.

An experiential course design focuses on providing students with practical knowledge, activities, assignments, and

experiences they can apply to their futures. Researchers have suggested that active learning results in more intense and more permanent learning. In contrast, a lecture design tends to emphasize theory over application. Therefore, an experiential design should provide more favorable outcomes for the student in terms of grades, percep-tions about the class, perceppercep-tions about the usefulness of the course, and satis-faction with the course than a lecture design, which led us to form the follow-ing hypothesis.

H2: An experiential course design will result in more positive student outcomes in grades, overall satisfaction with a course, student perceptions of how well a class was conducted, and student percep-tions of the usefulness of a course to their future careers than will a lecture design.

Participative learning is an active course design and therefore results in heightened student involvement. Any class design that facilitates more active learning should be superior to a tradi-tional lecture design on most outcomes. Participative learning has been shown to result in students feeling more involved and taking more ownership in a class. By helping to determine what types of assignments and classroom activities on which they will be judged, students should feel more satisfaction with a par-ticipative course design than with the lecture design. Therefore, a

participa-tive course design should provide more favorable outcomes for the student in terms of grades, perceptions about the class, perceptions about the usefulness of the course, and satisfaction with the course than will the lecture design. Because participative learning is a form of active learning, we postulated the fol-lowing relationship.

H3: A participative course design will result in more positive student outcomes in grades, overall satisfaction with a course, student perceptions of how well a class was conducted, and student percep-tions of the usefulness of a course to their future careers than will a lecture design.

The main emphasis of an experiential design is to provide students with prac-tical knowledge, activities, assignments, and experience that they can apply to their futures. The participative design does not have this same emphasis. Although both experiential and partici-pative course designs are active designs, they do not apply the same principles of learning. Students should be more satis-fied with a participative course design because they are partially responsible for developing the activities the course will pursue. However, the participative design does not include opportunities for students to actively practice the material they are learning; therefore, students should experience more nega-tive outcomes in terms of perceptions about the usefulness of the class.

Because of the nature of active learning and the fact that both experiential course designs and participative course designs are types of active learning, there is no theoretical or empirical evi-dence suggesting differences between the impact of these designs on student grades and student perceptions of how well the class was conducted. There-fore, we hypothesized the following.

H4: A participative design will result in higher levels of student satisfaction with a course than will an experiential design, but will result in more negative student perceptions of the usefulness of a course to their future careers. There will be no differences between participative and experiential designs on student grades and student perceptions of how well a class was conducted.

METHOD

We designed and delivered three courses, each using one of the designs being investigated in this study (Appen-dix B). Elements were infused into each course design to assure that students could differentiate between the designs and to insure that each design provided the appropriate type of learning experi-ence. The traditional lecture course was designed to present knowledge to the student through lectures given by the instructor. Evaluation of student perfor-mance in this class was based on read-ing the textbook, takread-ing notes durread-ing lectures, and performing well on the exams and assignments based on the textbook and lecture material.

The experiential course provided stu-dents with practical experience that they could use in an occupation related to the course. In this course, students com-pleted exercises and assignments that helped them understand how to apply the knowledge they gained during the semester. Students studied the actions of different companies through case stud-ies and tried to apply their responses to similar situations. They also completed exercises and assignments that gave them insights about themselves and “hands on” experiences in the class.

The participative course allowed stu-dents to have a great deal of control over how they would be evaluated by includ-ing them in the decisions of how the class would be conducted and the key FIGURE 1. Model of the impact of course design on student perceptions

and outcomes. Course Designs

Active designs Experiential Participative Passive designs

Traditional lecture

Student Perceptions

How class is conducted

Application of class to future career

Satisfaction with class

Student Outcomes

Grades

elements that would be included in the course requirements. Students partici-pated in syllabus design and decisions concerning grading options, voting on the course activities that would be grad-ed. In addition, about two-thirds through the semester, the instructors came up with three alternative grading options to help students focus on the last part of the semester and to reinforce their participation. Students could then choose one of these options instead of the design originally voted on at the beginning of the semester and were evaluated based on their chosen option. Finally, instructors used group work, presentations, in-class discussions, and in-class exercises, providing opportuni-ties for students to contribute informa-tion to each other in the classroom.

Toward the end of the semester in each of the targeted classes, we admin-istered a survey designed to measure the variables described in the hypotheses. We studied three classes, each of which used a different design (one lecture, one experiential, and one participative); we received 111 useable surveys. There were 60 students enrolled in the class with the traditional lecture design, 31 students enrolled in the class with an experiential design, and 20 students enrolled in the class with a participative design. Forty-seven students were male and 64 were female. Sixty-three percent (n= 70) of the students were Caucasian

and 33% (n= 37) were Hispanic, leav-ing 4% (n= 4) from other ethnic back-grounds. The average age of the student respondents was 23.77 years; 71% (n= 79) were aged 23 years or younger whereas 29% were aged older than 23 years, with the oldest student being 42 years old. Of the different majors in the classes, 42% (n = 47) were marketing majors, 36% (n= 40) were management majors, and 22% (n= 24) were majors in other business disciplines. Nearly all students were juniors (n= 48, 43%) or seniors (n = 55, 50%), but 2 students were sophomores and 6 were master’s students in business administration. The majority of the students were employed at least part time (n= 90, 81%) and most had several years of work experience (M

= 6.09).

The questionnaire also included a manipulation check designed to assess whether students experienced the key characteristics associated with each of the three course designs. Results of the manipulation check indicated that stu-dents perceived the three course designs differently, on the basis of the specific characteristics of each design. The questionnaire also included multiple-item measures for each of the self-reported outcomes (see Appendix C). We checked reliabilities for each of the three multiple-item measures using Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951). We converted the fourth outcome, a

stu-dent’s actual grade in a course, to its number equivalent. We then analyzed the hypothesized relationships using both regression analysis (ordinary least squares) and t tests (Table 1).

RESULTS

Results of the reliability analyses are as follows. Four items were designed to measure student percep-tions of how the class was conducted and this measure was reliable (Cron-bach’s α = .92). Six items were

designed to measure student percep-tions of the usefulness of the class to their future careers. This measure was also reliable (Cronbach’s α = .92).

Finally, nine items were designed to measure student satisfaction with the class. This measure was also found to be reliable (Cronbach’s α= .96).

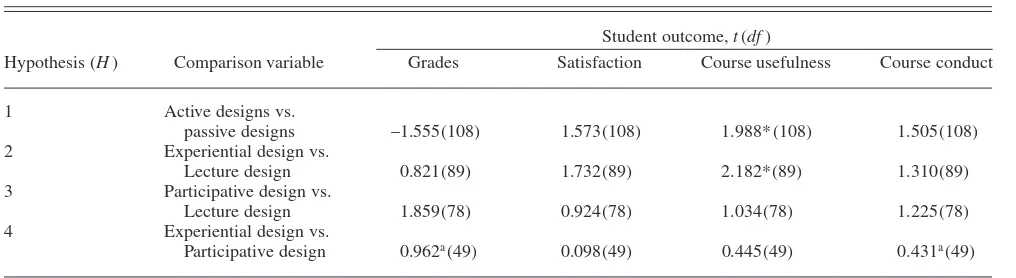

Regression analyses suggested that course design had no statistically signif-icant impact on the student outcome variables. However, to actually test the hypotheses, we performed t tests to compare the three course designs.

We combined active and passive designs and tested them against each other. Students perceived a course to be more useful to their future careers when the faculty member used an active course design as opposed to a passive course design,t(108) = 1.988,p< .05; however, the use of an active course

TABLE 1. Results of tTests of Hypotheses

Student outcome,t(df)

Hypothesis (H) Comparison variable Grades Satisfaction Course usefulness Course conduct

1 Active designs vs.

passive designs –1.555(108) 1.573(108) 1.988* (108) 1.505(108) 2 Experiential design vs.

Lecture design 0.821(89) 1.732(89) 2.182*(89) 1.310(89) 3 Participative design vs.

Lecture design 1.859(78) 0.924(78) 1.034(78) 1.225(78) 4 Experiential design vs.

Participative design 0.962a(49) 0.098(49) 0.445(49) 0.431a(49)

Note. H1= In all areas, active course designs will result in more positive student outcomes than passive course designs; H2= in all areas, an experiential course design will result in more positive student outcomes than a lecture design; H3= in all areas, a participative course design will result in more posi-tive student outcomes than a lecture design; H4= a participative design will result in higher levels of student satisfaction with a course than an experien-tial design, but will result in more negative student perceptions of the usefulness of a course to their future careers. For student grades and student per-ceptions of how well a class was conducted, there will be no differences between participative and experiential designs.

aNot significant as predicted.

*p< .05.

design did not impact student grades, student satisfaction with the course, or student perceptions about how well the class was conducted. Therefore,H1was only partially supported.

To better understand the differences between active and passive course designs, we used ttests to compare the specific course designs with each other. First, we compared an experien-tial design with a lecture design. Stu-dents perceived the experiential design to be significantly more useful to their future careers than was the lecture design,t(89) = 2.182,p< .05. Howev-er, as with the active versus passive results, we observed no significant dif-ferences with regard to student grades, student satisfaction with the course, nor student perceptions about how well the class was conducted. Therefore,H2

was only partially supported.

Contrary to predictions, when we compared the participative course design with the lecture design, we observed no significant differences with regard to any of the student outcome measures. There-fore,H3was not supported.

Finally, we compared the two active methods, experiential and participa-tive. We had expected the use of par-ticipative course design to result in higher levels of student satisfaction; however, results indicated no differ-ences in the level of student satisfac-tion between these two designs. We had also anticipated that the experien-tial course design would result in more positive perceptions of the usefulness of the course. We observed no differ-ences on this outcome variable. As expected, we observed no differences with regard to student grades or stu-dent perceptions of how well a class was conducted. Therefore, H4 was only partially supported.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study, though not entirely as predicted, provide valuable information for business educators on course design and the impact of

vari-ous types of designs on varivari-ous student outcomes. The results indicate that active course designs, specifically, an experiential design, result in students perceiving their learning to be more meaningful to their future jobs. The active designs did not result in higher grades, higher student satisfaction with a course, or more positive perceptions of how a course was conducted, which we did not expect. However, in no case was the traditional lecture design superior to the designs used to facili-tate active learning.

The nonsignificant findings in this study are also interesting. The most notable among these is the failure to find differences between a participative course design and the lecture design. The results indicated that there seems to be no reward for including students in the deci-sion process when designing a course. Also of note is the absence of differences observed in student outcomes when the two active designs are compared. The two forms of active course design used in this study resulted in no significant dif-ferences. The findings seem to indicate that instructors should incorporate active learning into their course designs if they wish students to see the relevance of the course to future careers.

This analysis was conducted using a small sample size and only one class for each type of course design. To be able to make stronger and more gener-al conclusions, the impact of a greater number of courses on a larger sample of students should be examined. In addition, many student characteristics, such as learning style or personality, might interact with the course designs to confound the findings. Further research should be conducted to attempt to identify the factors that might influence how meaningful and long lasting a business student’s edu-cation will be.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Dr. Sue Stewart Wingfield, Col-lege of Business, Texas A & M University–Corpus

Christi, 6300 Ocean Drive, FC 121, Corpus Christi, Texas 78412. E-mail: swingfield@cob. tamucc.edu

REFERENCES

Allen, D., & Young, M. (1997). From tour guide to teacher: Deepening cross-cultural competence through international experience-based educa-tion. Journal of Management Education, 21, 168–189.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–335.

Jones, V. F., & Jones, L. S. (1998). Comprehensive classroom management: Creating communities of support and solving problems.Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Kayes, D. C. (2002). Experiential learning and its critics: Preserving the role of experience in management learning and education. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1, 137–149.

King, P. M, & Kitchener, K. S. (1994). Develop-ing reflective judgment: UnderstandDevelop-ing and promoting intellectual growth and critical thinking in adolescents and adults. San Fran-cisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kitchener, K. S., & King, P. M. (1981). Reflective judgment: Concepts of justification and their relationship to age and education. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology,2, 89–116. Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning. Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Labinowicz, E., (1980). The Piaget primer: Think-ing, learnThink-ing, teaching. Menlo Park, CA: Addi-son-Wesley.

Mills-Jones, A. (1999, December). Active learn-ing in IS education: Chooslearn-ing effective strate-gies for teaching large classes in higher educa-tion. Proceedings of the 10th Australasian Conference on Information Systems(pp. 5–9). Wellington, New Zealand.

Miner, F. C., Jr., Das, H., & Gale, J. (1984). An investigation of the relative effectiveness of three diverse teaching methodologies. Organi-zational Behavior Teaching Review, 9(2), 49–59.

Paul, R. (1990). Critical thinking: What every per-son needs to survive in a rapidly changing world. Rohnert Park, CA: Sonoma State University, Center for Critical Thinking and Moral Critique. Thornton, G. C., III, & Cleveland, J. N. (1990).

Developing managerial talent through simula-tion. American Psychologist,45, 190–199. Van Eynde, D. F., & Spencer, R.W. (1988).

Lec-ture versus experiential learning: Their differ-ential effects on long-term memory. Organiza-tional Behavior and Teaching Review, 12(4), 52–58.

Whetten, D. A., & Clark, S. C. (1996). An inte-grated model for teaching management skills.

Journal of Management Education, 20, 152–181.

Whetten, D. A., Windes, D. L., May, D. R., & Bookstaver, D. (1991). Bringing management education into the mainstream. In J. D. Bigelow (Ed.),Managerial skills: Explorations in prac-tical knowledge (pp. 23–40). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.