Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ubes20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:57

Journal of Business & Economic Statistics

ISSN: 0735-0015 (Print) 1537-2707 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ubes20

Consumer Search Behavior in the Changing Credit

Card Market

Sougata Kerr & Lucia Dunn

To cite this article: Sougata Kerr & Lucia Dunn (2008) Consumer Search Behavior in the Changing Credit Card Market, Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 26:3, 345-353, DOI: 10.1198/073500107000000133

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1198/073500107000000133

Published online: 01 Jan 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 100

Consumer Search Behavior in the Changing

Credit Card Market

Sougata K

ERRConsumer Risk Modeling and Analytics, JP Morgan and Chase Co., Columbus, OH 43240 (sougata.kerr@chase.com)

Lucia D

UNNDepartment of Economics, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210 (Dunn.4@osu.edu)

This article investigates whether search costs inhibit consumers from searching for lower credit card in-terest rates. The results provide evidence that the credit card search environment has changed since the mid-1990s. Using the2001 Survey of Consumer Finances, we model consumers’ propensity to search and their probability of being denied credit simultaneously and find that larger credit card balances induce cardholders to search more even though they face a higher probability of rejection. This result may be re-lated to the high volume of direct solicitation, combined with disclosure requirements, which has lowered the cost of search to find lower interest rates.

KEY WORDS: Revolving credit; Search costs; Switch costs.

1. INTRODUCTION

Credit card balance switching and the consumer search in-volved in this process have become important issues in the banking community as more cardholders seek to move their revolving credit to lower cost lenders. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, research in this area tended to focus on con-sumers’ lack of interest rate sensitivity and the inhibiting effect of high search costs in this market. These were among the main reasons put forward to explain the lack of interest rate com-petition in the credit card market and persistent high rates in this period. We find that consumer behavior has changed since the early 1990s. Consumers now display more willingness to shop around for lower rates. Easy access to rate information on the Internet and in the large volume of mailed solicitations, as well as disclosure requirements such as those in the Truth in Lending Act (officially the “Fair Credit and Charge Card Dis-closure Act” of 1988), have contributed to this changing envi-ronment by providing easier access to interest rate information and thus facilitating the “search and switch” behavior of con-sumers. These and other factors may be partially responsible for the more competitive environment in the 1990s credit card market.

Here we will examine the determinants of consumer search propensities with particular emphasis on those cardholders who carry a high balance. High-balance cardholders are of special interest because they potentially have the most to gain from search; and at the same time, they face a higher probability of rejection. Previous researchers have argued that a greater like-lihood of rejection is likely to deter the search propensity of the high-balance-carrying consumer due to substantial search costs in this market. We will analyze (a) the effect of large bal-ances on the consumer’s probability of credit application rejec-tion, and (b) how these factors—large balances and rejection probability—affect consumers’ search propensities. In testing the search-cost hypothesis, we deal with the issue of endogene-ity between consumers’ search and the likelihood of rejection with a simultaneous equations model.

Our results show that consumers in the current credit card market are interest-rate sensitive. Furthermore, we find no evi-dence that search costs deter consumer search for lower rates.

Whereas credit application rejection is found to have a damp-ening effect on search, the possible interest savings from a suf-ficient amount of balances is found to overcome the effect of the rejection. In the next section we review the relevant litera-ture on this market and recent changes in the market environ-ment. Section 3 discusses our methodology and improvements in available data. Section 4 presents our empirical results, and Section 5 summarizes our findings and conclusions.

2. BACKGROUND AND PREVIOUS LITERATURE ON

THE CREDIT CARD MARKET

Consumer revolving credit, which includes credit card debt as its principal component, has been the fastest growing seg-ment of the U.S. consumer loan market in recent years (Durkin 2000). In the 1980s a peculiar feature of this market was the lack of price competition between issuers, as credit card rates remained high (around 18%) and downwardly sticky. This be-havior was puzzling given the fact that the market was func-tionally deregulated by 1982 and saw the entry of nearly 4,000 firms during the ensuing decade.

Early work on credit card markets presented consumer search, or the lack of it, as an important factor in the high and sticky interest rates of that period. Ausubel (1991) argued that many consumers underestimated their borrowing potential, which made them less sensitive to interest rates. In addition to interest rate insensitivity, he cited the inhibiting nature of high search costs, which prevented consumer search for lower rates and allowed issuers to keep rates high in this market. (For other developments in search models, see Mortensen and Pissarides 1999.)

Other researchers explained the observed high levels of in-terest rates by pointing to various unique features of credit card debt such as the noncollaterized characteristic of credit cards (Mester 1994); open-ended revolving credit lines (Park 1997);

© 2008 American Statistical Association Journal of Business & Economic Statistics July 2008, Vol. 26, No. 3 DOI 10.1198/073500107000000133

345

346 Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, July 2008

and the liquidity services offered by credit cards under con-sumption uncertainty (Brito and Hartley 1995). However, the lack of price competition was considered the dominant factor in this literature.

The major empirical article on credit card search by Calem and Mester (1995) used 1989 Survey of Consumer Finances

(SCF) data and found results that were consistent with con-sumers’ reluctance to search for lower rates due to high search costs in this market. That research did not model consumer search explicitly but reached this conclusion by examining the determinants of credit card balances, one of which was con-sumer search. They found (a) that credit rejection is posi-tively related to the level of balances because large outstand-ing balances send a signal of high risk to banks. More im-portantly, they found (b) that the level of credit card balances is negatively related to search, indicating that high-balance-carrying consumers are less willing to search for lower rates. Together these results were indicative of both consumer in-sensitivity to interest rates and high search costs in this mar-ket. According to the search-cost hypothesis, the impact of past rejections on the search propensity of the consumer would depend crucially on the magnitude of search costs prevailing in the market. If search costs are negligible, then a higher likelihood of rejection is unlikely to have a major impact on consumers’ search behavior. On the other hand, if these costs are high, then a high probability of rejection will ad-versely affect the search propensities of balance-carrying sumers. The negative relation between card balances and con-sumer search led Calem and Mester to conclude by inference that higher balance cardholders, facing a greater risk of rejec-tion, will have higher expected search costs and will search less.

Other research that suggested search costs are an issue to consumers in this period is that of Stango (2002). He used data from the Card Industry Directory (listing data for the 250 largest card issuers) for the period from 1989 to 1994 and found that switching costs explain over one-quarter of the within-firm variation in credit card interest rates for commercial banks.

2.1 Relevant Changes in the Credit Card Market

Beginning in 1991, credit card interest rates started to decline after remaining stable at around 18% for the previous 20 years. According to the Federal Reserve Board’s 2001 Annual Re-port, rates declined gradually until 1994, and thereafter the average rate has fluctuated in accordance with the prime rate (reflecting the marginal cost of funds). This decline in credit card interest rates during the 1990s was in part a result of price competition as banks pursued a strategy to attract cus-tomers by offering introductory low rates on easily imple-mented balance transfers, thereby encouraging customers to roll over balances from competing firms. The number of di-rect solicitations reached 5 billion annually by the year 2001, almost four solicitations per month per American household (see Federal Reserve Board Annual Report, 2001). This in-creased competition among banks may have been responsi-ble for a somewhat reduced differential between the prime rate and the average credit card rate over the decade of the 1990s. Credit card rates had been stuck around the 18% level

throughout the 1980s up to 1991. The year 1991 makes for an easy comparison since the prime rate (cost of funds) in 1998 was about the same as in 1991, around 8.5%. However, the credit card rate was 4 percentage points lower in 1998 compared to 1991, from 18% to 14%. Hence the spread be-tween credit card rates and the prime rate decreased over that decade.

At the same time, consumerrevolvingcredit outstanding be-came the fastest growing component of the consumer loan mar-ket, doubling between 1991 and 1997, from $247 billion to $514 billion (Yoo 1998). Black and Morgan (1998) and Yoo (1998) showed that democratization of credit, and later an in-crease in overall indebtedness of U.S. households, were re-sponsible for this growth. This prompted a growing literature on the issue of obtaining and utilizing credit limits and the question of consumers being credit-constrained. Research in this area includes work by Jappelli (1990), Jappelli, Pischke, and Souleles (1998), Dunn and Kim (1999), Gross and Soule-les (2002a,b), Haliassos and Reiter (2003), and Castronova and Hagstrom (2004). In addition to providing evidence that consumers are credit-constrained, some of these studies have also found indications that consumers have target utilization rates.

With these new factors in the credit card market, researchers have begun to re-examine the search and switch cost issue. Crook (2002) modeled the effect of (a) credit rejection on bal-ances and (b) balbal-ances on search behavior separately, repeat-ing Calem and Mester’s test usrepeat-ing the 1998SCF, and he did not find a significant relationship between high balances and search. Furthermore, based on results from a search model, he concluded that the problem of adverse selection in the credit card market may have abated in recent years, as the search propensities of consumers with poor payment histories are not different from the search propensities of consumers with bet-ter payment histories. The current article differs from earlier work by modeling search behavior explicitly on both past re-jections and card balances, as well as exploring the possible endogeneity that may exist between shopping behavior and fre-quency of credit rejections. This specification allows us to test the countereffects of balance-carrying and credit rejection and checks whether the indirect effect of large balances through credit rejection is sufficient to deter the direct benefit achieved from search. Kim, Dunn, and Mumy (2005) used a new set of credit card data from a monthly household survey taken from 1996 to 2002 to examine the equilibrium interest rates result-ing from the different search motives of convenience-users and borrowers in this market. They found that borrowers end up with lower interest rates than convenience-users. Berlin and Mester (2004) examined a variety of consumer search mod-els with 1981–1986 bank data to see if, in the time period when search costs were presumably higher, such theoretical models could explain the distribution of credit card interest rates that prevailed. Berlin and Mester concluded that a drop in switching costs may not be the main explanation for the decline in credit card interest rates in the 1990s. Calem, Gordy, and Mester (2006) looked at adverse selection and switching costs in the credit card market using more recent SCF data and the following novel treatments: (a) controls for the possi-bility that households that are temporarily liquidity-constrained

will run up larger balances, and (b) incorporation of a “pseudo credit score” which the authors themselves constructed for sam-ple members. Their findings suggested that some information-based barriers to switching may still exist, but that the level of credit card balances at which they become effective may have increased.

In the current article, we use the 2001SCFdata to simulta-neously model search propensity and likelihood of credit card rejection. We hypothesize that there is a trade-off for consumers between the cost of search and likelihood of rejection on the one hand and the potential savings from lower finance charges on the other hand. Past turndown and high credit card balances should have a significant negative impact on shopping behav-ior, as it raises the likelihood of future rejection; but high credit card balances, although also potentially signaling risk, should not deter shopping behavior if the expected savings from lower finance charges are sufficiently high. We thus directly test the issue of how the factors of balance-carrying and credit rejection affect search. We find that in recent years the balance-carrying consumers search for better credit terms in spite of the dampen-ing effect of past credit card denials. These results are probably related to the large volume of solicitations and federal disclo-sure requirements, which forced issuers to report upfront their most important contract terms. These phenomena have made comparison shopping for credit card terms much easier and less costly. This also suggests that a factor in the increased price competition in the last decade may have been a change in con-sumer behavior, with greater concon-sumer sensitivity to credit card interest rates and more interest rate search by debt-carrying credit card users. Our results are consistent with the results of Gross and Souleles (2002a) who found that credit card debt has become increasingly interest-elastic and, more importantly, ap-proximately half of the effect is the result of balance switch-ing.

3. THE EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION

3.1 Data

Here we use data from the 2001 Survey of Consumer Fi-nances, a more recent round of theSCFthan was used in some of the earlier work cited here. These data used theSCF sam-ple weights, and all results are based upon the average of the fiveSCFimplicates. See Montalto and Sung (1996), and Ken-nickell (1998). This dataset contains improved variables specif-ically formulated for the credit card market. The proxy for con-sumer search used in this paper,Shop, is constructed from the question that collects information on consumers’ propensity to search before making decisions related to credit and borrow-ing only. The responses to the shoppborrow-ing question range from “almost no shopping” through “moderate level of shopping” to “a great deal of shopping.” Shop is assigned the value 1 for “moderate to high level of shopping” and 0 for all other cat-egories. Prior rounds of theSCF lumped search for credit or loan products together with search for deposit products (sav-ings/investments), and this inability to distinguish between the two types of search in the data created unavoidable measure-ment error in earlier research on credit card search behavior.

The response to the currentShopquestion could apply to sev-eral types of credit products, but we assume that the propen-sities to shop in different credit markets should be correlated. Although one might argue that the likely gains from shopping would be greater for a mortgage (making them more likely to be a target for shopping), the transactions costs associated with shopping for mortgages are also correspondingly much higher than for credit cards in the current environment of un-solicited mail offers. This cost factor would work against this argument. Also, in our empirical analysis, we control for other types of credit instruments through a Monthly Payment to In-comevariable which includes mortgage payments and auto pay-ments.

Another importantSCFvariable used here is credit card re-jection, Turndown. This credit card-specific variable is also available only in recent rounds of theSCF,whereas a variable that referred to rejection for all credit products was used in ear-lier works.Turndownequals 1 if a credit card application has been rejected and 0 otherwise.

Detailed information on a broad array of assets and liabilities held by consumers, such as forms of account ownership, mini-mum required payments on loans, frequency of these payments, and so on, allows us to construct the relevant variables that cap-ture the income and expendicap-ture stream of each consumer along with their search propensities, credit access, and demographic information. The sample used here focuses only on those house-holds that have at least one bank credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Amex, and Discover).

3.2 Methodology

The approval of credit depends on a lender’s a priori estimate of the default thresholds of consumers based on various signals of credit risk. Therefore, the lender’s rejection of a credit appli-cation is modeled using an index function of creditworthiness for consumer ‘i,’Ci(X1i), that depends on a vector capturing an individual’s credit characteristics,X1i. A credit application

is rejected whenCi(X1i) <C¯, whereC¯ is the threshold level for granting credit. WritingCi(X1i)as a first-order approximation of the variables and normal error, we get the following probit model forTurndown:

Ti∗= ¯C−C(X1i)=δ1·X1i+ε1i, (1) whereTi∗>0 results in rejection and Ti∗≤0 results in credit approval.

On the other hand, a consumer searches for better credit terms if the utility derived from search through lower finance charges (after adjusting for search costs) outweighs his util-ity from not searching. The search behavior of consumeri is therefore modeled using the latent variableS∗i =Vsi(X2i, φi)−

Vnsi(X2i,0), whereVsiandVnsidenote the utility derived from searching and not searching, respectively. The utility from search depends on a vector of individual specific characteris-tics X2i and also on φi, which represents both pecuniary and nonpecuniary costs of search and in itself depends onX2i.

Writ-ing the utilities as a linear approximation of the individual spe-cific characteristics and a normal error, the determinants of con-sumer search can then be analyzed with the following probit equation:

S∗i =Vsi(X2i, φi)−Vnsi(X2i,0)=δ2·X2i+ε2i, (2)

348 Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, July 2008

where individual i engages in search if S∗i >0 and does not search whenS∗i ≤0.

Since outstanding card balances and a consumer’s past re-jections,Turndowni, are included inX2i, (2) provides a direct test for the hypothesis that consumers with large balances, who are more subject to rejection, will be inhibited from shopping around for credit terms because of their higher expected cost of search.

3.3 Endogeneity

It can be argued that because the underlying hypothesis is that a higher probability of rejection makes high-balance con-sumers reluctant to comparison shop, then (2) should include the latent variableTi∗ rather than the indicator variable for re-jectionTurndown. Also, it might be argued that consumers with a higher search propensity subject themselves to more rejection. To account for this latter possibility, we explore the endogene-ity betweenShopandTurndown. RewritingX1i=(S∗i,Z1i)and

X2i=(Ti∗,Z2i), we estimate the following two probit equations simultaneously using a two-step maximum likelihood proce-dure (Mallar 1977):

Ti∗=α1·S∗i +β1·Z1i+ε1i,

(3)

S∗i =α2·Ti∗+β2·Z2i+ε2i.

We follow Murphy and Topel (1985) to calculate the as-ymptotic variance–covariance matrix of the second-stage co-efficients. This accounts for the interdependence of the error terms and the fact that the unobservable regressors have been estimated in calculating the second-step coefficients (see App. A for details).

4. RESULTS

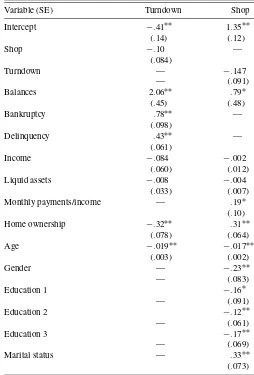

Table 1 presents the results of the separate probits in (1) and (2). Column 1 is the fit of the credit card rejection vari-ableTurndown(1) to the search variableShopand outstanding balances. Column 2 presents the fit of Shop(2) to Turndown

and outstanding balances.TurndownandShopare both binary variables taking the value 1 for having incurred credit appli-cation rejection and engaging in search behavior, respectively. We also include control variables for income, bankruptcy and delinquency histories, average monthly payments on consumer loans and monthly rents to income, liquid assets, homeowner-ship, and socioeconomic characteristics. A detailed description of variables is presented in Appendix B, Table B.1, and the cor-relations between regressors are presented in Appendix B, Ta-ble B.2.

We see from Table 1 that the level of outstanding balances has a positive and highly significant effect on credit card re-jection, consistent with the hypothesis that banks regard high-balance consumers as high risks. (Note that the variable rep-resenting consumer search—Shop—is not significant in the fit for credit card rejection.) Also, column 2 shows that credit re-jection has a negative effect on search (although not quite at the 10% significance level). Nevertheless, the level of outstanding

Balancesstill has a positive and significant effect on consumer search even in the face of rejection. Also, it is important to con-sider the relative magnitude of the effects. The coefficients on

Table 1. Independent probit estimates forTurndownandShop

Variable (SE) Turndown Shop

Monthly payments/income — .19∗

(.10)

NOTE: ∗∗Significant at 5% level of confidence.∗Significant at 10% level of confidence. N=3,193.

BalancesandTurndownimply that the negative impact from each one-percentage point increase in the expected probabil-ity of turndown is offset by an extra $190 in credit card bal-ances. (The average credit card balance among revolvers was $9,205 in 2004 according to Bankrate.com.) Thus, even though rejection is a factor in the credit card market, our results are in contrast to the earlier hypotheses that balance-carrying con-sumers (a) are insensitive to interest rates, and (b) are impeded by costs from searching in this market. In today’s environment, finance charge considerations appear to offset the search and switch costs that might exist for high-balance consumers. Even though high-balance consumers are more likely to be denied credit, this does not deter them from searching for lower inter-est rates.

4.1 Two-Stage Estimates

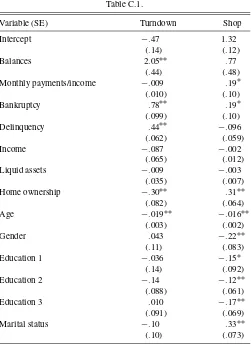

We now explore the link betweenTurndownandShop fur-ther by estimating the equations accounting for endogeneity be-tween consumers’ search and the likelihood of rejection, since greater search is also likely to expose a consumer to more rejec-tion. For identification purposes, bankruptcy and delinquency are used as instruments for Turndown and omitted from the

Shopequation. Clearly, consumers with a past record of bank-ruptcies and delinquencies are more likely to get rejected by credit issuers. On the other hand, there is no theory or solid em-pirical evidence suggesting that past bankruptcy filings or delin-quency actually affect shopping behavior of individuals. Even if there is a discouraging effect, it should be through the Turn-downvariable. The strength of bankruptcy and delinquency in theTurndownreduced-form equation (App. C) supports their use as instruments forTurndown.

Likewise, the consumer’s average monthly payments to come, along with gender, education, and marital status, are in-cluded as instruments in theShopequation and are omitted from theTurndownequation. Consumers having to make high aver-age monthly payments relative to income will be sensitive to the price portion of any credit contract and will be more likely to search for lower interest rates. On the other hand, average monthly payments to income need not convey a signal of credit risk to banks—especially since reliable income data are not available to credit card banks—and hence are excluded from theTurndownequation. Likewise, there is no evidence suggest-ing that the socioeconomic variables should affectTurndown. (Age is not used as an instrument forShopbecause it can af-fectTurndown.Unlike other demographic characteristics, Fair Lending Laws are explicit against discrimination toolder appli-cants, but this does not prevent lenders from rejecting younger applicants.) The reduced-form results, which are presented in Appendix C, show that all instruments forShopare significant in theShopequation but not significant in theTurndown equa-tion.

Finally, it has been suggested to us that those with a history of delinquency in the last 12 months (as ascertained in theSCF) may have a different attitude toward credit card search than those without this history. We have therefore reestimated the

Shopequation with the latent variableTurndowndecomposed into two components: one that reflects the effect of a history of delinquency and holds all other factors constant; and one that holds delinquency constant at zero and considers all other factors. These results, which are equivalent to removing delin-quency as an instrument, are presented in Appendix D for those who would like to further examine the effect of delinquency.

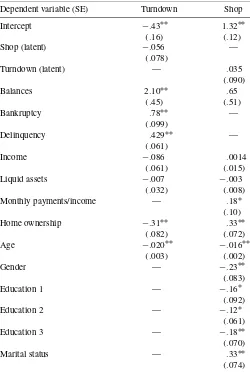

The maximum likelihood estimates of the simultaneous two-equation probit model are reported in Table 2. The results do not indicate the presence of endogeneity.

5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Credit card debt has been the fastest growing segment of the U.S. consumer loan market in the last two decades. One line of research on credit cards has focused on cardholder search behavior as a primary factor behind the lack of price compe-tition in this market until the early 1990s. Since that period, a large volume of direct solicitations featuring full disclosure of rate and other contract terms, as required by the Truth in Lend-ing Act of 1988, has become common; and this has contributed to a change in consumer behavior. Here we examine consumer search behavior using the more recent data of the2001 Survey of Consumer Financeand a direct model specification for con-sumer search. We also investigate the possible endogeneity of

Table 2. Structural ML estimates ofShopandTurndown

Dependent variable (SE) Turndown Shop Intercept −.43∗∗ 1.32∗∗

(.16) (.12)

Shop (latent) −.056 —

(.078)

Turndown (latent) — .035

(.090)

Monthly payments/income — .18∗

(.10)

NOTE: ∗∗Significant at 5% level of confidence.∗Significant at 10% level of Confidence. N=3,193.

consumer search and the probability of rejection for the high-balance cardholders.

We find that in the current market, high-balance-carrying consumers search for lower credit card rates in spite of their higher likelihood of rejection. Our results show that the nega-tive impact from each one-percentage-point increase in the ex-pected probability of turndown is offset by an extra $190 in bal-ances. Thus, interest savings on large credit card balances can outweigh the discouraging effect of credit rejection on search in this market.

APPENDIX A: CORRECTED ASYMPTOTIC VARIANCE–COVARIANCE MATRIX

FOR TWO–STEP MLE

The reduced-form equations of the model in (3) are as fol-lows:

Ti∗=1·Zi+e1i, (3a)

S∗i =2·Zi+e2i, (3b) whereZi=(Z1i,Z2i). First, consistent estimates of the reduced-form parameters are obtained by maximizing the marginal like-lihood functions constructed from (3a) and (3b) separately. Let

350 Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, July 2008

L1 be the likelihood function for the first-stage reduced-form

equation forTurndowni,

L1= n

i=1

Ti·log{F(1·Zi)} +(1−Ti)·log{1−F(1·Zi)}.

MaximizingL1givesTˆi∗(ˆ1·Zi). Second, this estimated prob-ability is substituted for its unobserved counterpart in the struc-tural equation, and the likelihood function for the strucstruc-tural equation is then maximized with respect to its parameters. IfL2

is the likelihood function for the second-stage structural equa-tion forShop, then substitutingTˆi∗(ˆ1·Zi)forTurndowniinL2

gives

L2=

n

i=1

Si·logF(α2· ˆTi∗(1·Zi)+β2·Z2i)

+(1−Si)·log1−F(α2· ˆTi∗(1·Zi)+β2·Z2i). MaximizingL2gives consistent estimates(αˆ2,βˆ2).

Writing θ2 =(α2, β2), the correct asymptotic variance–

covariance matrix for the second-stage parameters (Murphy and Topel 1985) is given as

var(θ2)=V2−1+V −1 2 [CV

−1

1 C/−RV −1 1 C

′

−CV1−1R]V2−1,

where

V1= −E

∂2L1

∂1∂′1

,

V2=E

∂L2

∂θ2

∂L

2

∂θ2

′

,

C=E∂L2

∂1

∂L

2

∂θ2

′

,

R=E∂L1

∂1

∂L

2

∂θ2

′

.

These matrices are replaced by their estimated counterparts in the calculation of the standard errors. The above procedure is followed for the structural equationTurndownalso.

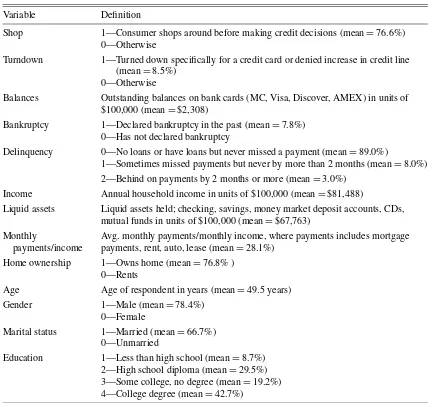

APPENDIX B: VARIABLE DEFINITIONS AND CORRELATIONS

Table B.1. Definitions of variables

Variable Definition

Shop 1—Consumer shops around before making credit decisions (mean=76.6%) 0—Otherwise

Turndown 1—Turned down specifically for a credit card or denied increase in credit line (mean=8.5%)

0—Otherwise

Balances Outstanding balances on bank cards (MC, Visa, Discover, AMEX) in units of $100,000 (mean=$2,308)

Bankruptcy 1—Declared bankruptcy in the past (mean=7.8%) 0—Has not declared bankruptcy

Delinquency 0—No loans or have loans but never missed a payment (mean=89.0%)

1—Sometimes missed payments but never by more than 2 months (mean=8.0%) 2—Behind on payments by 2 months or more (mean=3.0%)

Income Annual household income in units of $100,000 (mean=$81,488)

Liquid assets Liquid assets held; checking, savings, money market deposit accounts, CDs, mutual funds in units of $100,000 (mean=$67,763)

Monthly Avg. monthly payments/monthly income, where payments includes mortgage payments/income payments, rent, auto, lease (mean=28.1%)

Home ownership 1—Owns home (mean=76.8% ) 0—Rents

Age Age of respondent in years (mean=49.5 years)

Gender 1—Male (mean=78.4%)

0—Female

Marital status 1—Married (mean=66.7%) 0—Unmarried

Education 1—Less than high school (mean=8.7%) 2—High school diploma (mean=29.5%) 3—Some college, no degree (mean=19.2%) 4—College degree (mean=42.7%)

K

err

and

Dunn:

Consumer

Search

Beha

vior

351

Table B.2. Correlations between regressors for both equations

Weighted Correlation matrix

Monthly

Liquid payments/ Home Marital

_NAME_ Balances Income assets income ownership Age Gender status Education Bankruptcy Delinquency

Balances 1.000 .021 −.048 .005 −.035 −.094 .022 .016 .038 .007 .068

Income .021 1.000 .331 −.017 .105 .004 .108 .114 .155 −.042 −.052

Liquid assets −.048 .331 1.000 −.009 .073 .104 .034 .044 .090 −.043 −.040

Monthly .005 −.017 −.009 1.000 −.055 −.038 .000 −.041 −.004 −.002 .095

Payments/ Income

Home −.035 .105 .073 −.055 1.000 .279 .209 .289 .019 −.054 −.143

ownership

Age −.094 .004 .104 −.038 .279 1.000 −.055 −.005 −.126 −.026 −.133

Gender .022 .108 .034 .000 .209 −.055 1.000 .710 .067 −.044 −.061

Marital status .016 .114 .044 −.041 .289 −.005 .710 1.000 .038 −.019 −.039

Education .038 .155 .090 −.004 .019 −.126 .067 .038 1.000 −.077 −.075

Bankruptcy .007 −.042 −.043 −.002 −.054 −.026 −.044 −.019 −.077 1.000 .032

Delinquency .068 −.052 −.040 .095 −.143 −.133 −.061 −.039 −.075 .032 1.000

352 Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, July 2008

APPENDIX: C: FIRST–STEP REDUCED-FORM ESTIMATES FOR TWO–STEP ML ESTIMATES OF Shop AND Turndown

Table C.1.

Monthly payments/income −.009 .19∗

(.010) (.10)

NOTE: ∗∗Significant at 5% level of confidence.∗Significant at 10% level of confidence. N=3,193.

[Received February 2004. Revised January 2007.]

REFERENCES

Ausubel, L. M. (1991), “The Failure of Competition in the Credit Card Market,”

American Economic Review, 81, 50–81.

Berlin, M., and Mester, L. J. (2004), “Credit Card Rates and Consumer Search,”

Review of Financial Economics13, 179–198.

Black, S., and Morgan, D. P. (1998), “Risk and the Democratization of Credit Cards,” Research Paper 9815, Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Brito, D. L., and Hartley, P. R. (1995), “Consumer Rationality and Credit

Cards,”Journal of Political Economy, 103, 400–433.

Calem, P. S., Gordy, M. B., and Mester, L. J. (2006), “Switching Costs and Adverse Selection in the Market for Credit Cards: New Evidence,”Journal of Banking and Finance, 30, 1653–1685.

Calem, P. S., and Mester, L. J. (1995), “Consumer Behavior and Stickiness of Credit Card Interest Rates,”American Economic Review, 85, 1327–1336. Castronova, E., and Hagstrom, P. (2004), “The Demand for Credit Cards:

Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finances,”Economic Inquiry42, 304–318.

Crook, J. (2002), “Adverse Selection and Search in the Bank Credit Card Mar-ket,” working paper, Credit Research Centre, University of Edinburgh. Dunn, L. F., and Kim, T. H. (1999), “An Empirical Investigation of Credit Card

Default: Ponzi Schemes and Other Behavior,” Working Paper 99-13, Ohio State University, Dep. of Economics.

Durkin, T. A. (2000), “Credit Cards: Use and Consumer Attitudes,”Federal Reserve Bulletin, 86, 623–634.

Federal Reserve Board (2001), “88th Annual Report 2001,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

APPENDIX D: ALTERNATIVE STRUCTURAL ML ESTIMATES OF Shop USING TWO COMPONENTS

FOR TURNDOWN—WITH AND WITHOUT

Turndown (latent)—with delinquency history −.22

(.14)

Turndown (latent)—without delinquency history .24∗

(.12)

Balances .28

(.54)

Monthly payments/income .19∗

(.10)

Income .019

(.017)

Liquid assets −.001

(.008)

Home ownership .38∗∗

(.076)

Marital status .35∗∗

(.074)

NOTE: ∗∗Significant at 5% level of confidence.∗Significant at 10% level of confidence. N=3,193. Table suggests that consumers who have been turned down because of past delinquency are discouraged from shopping, whereas those turned down because of other credit risk factors, including high balances, are not.

Gross, D. B., and Souleles, N. S. (2002a), “Do Liquidity Constraints and Inter-est Rates Matter for Consumer Behavior? Evidence From Credit Card Data,”

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 149–185.

(2002b), “An Empirical Analysis of Personal Bankruptcy and Delin-quency,”Review of Financial Studies, 15, 319–347.

Haliassos, M., and Reiter, M. (2003), “Credit Card Debt Puzzles,” working pa-per, University of Cyprus and Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Jappelli, T. (1990), “Who Is Credit Constrained in the U.S. Economy,” Quar-terly Journal of Economics, 105, 219–234.

Jappelli, T., Pischke, J.-S., and Souleles, N. S. (1998), “Testing for Liquidity Constraints in Euler Equations With Complementary Data Sources,”Review of Economics and Statistics, 80, 251–262.

Kennickell, A. B. (1998), “Multiple Imputation in the Survey of Con-sumer Finances,” Federal Reserve BoardSCF Bibliography, available at

www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/oss/oss2/papers/impute98.pdf.

Kim, T. H., Dunn, L. F., and Mumy, G. E. (2005), “Bank Price Competition and Asymmetric Consumer Responses to Credit Card Interest Rates,”Economic Inquiry, 43, 344–353.

Mallar, Ch. D. (1977), “The Estimation of Simultaneous Probability Models,”

Econometrica, 45, 1717–1722.

Mester, L. J. (1994), “Why Are Credit Card Rates Sticky?”Economic Theory, 4, 505–530.

Montalto, C. P., and Sung, J. (1996), “Multiple Imputation in the 1992 Survey of Consumer Finance,”Financial Counseling and Planning, 7, 133–146.

Mortensen, D. T., and Pissarides, C. (1999), “New Developments in Models of Search in the Labor Market,” inHandbook for Labor Economics (3B), eds. O. Ashenfelter and D. Card, Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Murphy, K. M., and Topel, R. H. (1985), “Estimation and Inference in Two-Step Econometric Models,”Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 3, 370–379.

Park, S. (1997), “Option Value of Credit Lines as an Explanation of High Credit Card Rates,” Research Paper 9702, Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Stango, V. (2002), “Pricing With Consumer Switching Costs: Evidence From

the Credit Card Market,”Journal of Industrial Economics, 50, 475–492. Yoo, P. S. (1998), “Still Charging: The Growth of Credit Card Debt Between

1992 and 1995,” business review, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.