Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Building Context-Based Library Instruction

Malu Roldan & Yuhfen Diana Wu

To cite this article: Malu Roldan & Yuhfen Diana Wu (2004) Building Context-Based Library Instruction, Journal of Education for Business, 79:6, 323-327, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.79.6.323-327 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.79.6.323-327

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 45

View related articles

he dawn of the information age and the knowledge-based economy was widely recognized decades ago by many scholars and business leaders. A decade ago, Davis and Botkin (1994) remarked that “the next wave of economic growth is going to come from knowledge-based businesses—smart products and services will turn companies into educators, and customers into lifelong learners” (p. 165). According to business manage-ment guru Peter Drucker (1995, p. 58), “enterprises are paid to create wealth” and executives need information to make informed decisions. Four types of information are generally required: foundation information, productivity information, competence information, and information about scarce resources. Drucker coined the term “knowledge worker” to identify this newly emerging dominant group, which comprises more than one third of the workforce in the United States. These workers need to build the ability to identify, locate, eval-uate, and use information effectively, legally, and ethically. Above all, knowl-edge workers need to develop a habit of continual learning.

Pronouncements and predictions regarding the information age have cre-ated much soul searching among educa-tors, who are pondering questions such as the following: Are today’s students well prepared for the challenges of this

information age? Do they possess the skills and motivation required for life-long, continual learning? How can edu-cators help students to better prepare and improve students’ information liter-acy skills? Do institutions identify and evaluate accountability and learning outcomes for students?

In this article, we address the following question: Does context-based library instruction result in an improvement of team-based research and writing, key skills of the information age? To answer this question, we conducted a study to assess the effectiveness of context-based library instruction sessions in teaching students the skills required for effective use and evaluation of information. The design of the sessions was the result of close collaboration between faculty

members and a librarian whose focus was on management information systems education. The library instruction ses-sions included material on the following areas:

• Where to find information beyond commonly available Web resources such as Google and Yahoo;

• How to build search strategies, including the use of Boolean operators, keywords, and control language to nar-row the search, and how to improve pre-cision and hit rates;

• How to evaluate retrieved informa-tion for relevancy and accuracy; and

• How to cite information to recognize authors and use of information properly.

We selected library resources demon-strated during the session to match the unique research needs of the students in the course. Furthermore, faculty mem-bers and librarians reinforced the use of the resources as they were assisting stu-dents with their research over the course of the semester. We used pre- and posttests to assess the effects of these library instruction sessions on undergrad-uate students’ research and writing skills.

Information Literacy Guidelines and Policies

As early as 1992, the U.S. Department of Labor identified five competencies

Building Context-Based

Library Instruction

MALU ROLDAN YUHFEN DIANA WU San Jose State University

San Jose, California

T

ABSTRACT. Information overload and rapid technology changes are among the most significant challenges to all professions, particularly infor-mation technology workers and librar-ians. Little is known about the effec-tiveness of partnerships among librarians and faculty members that result in context-based library instruc-tion. In this study, the authors evaluat-ed one particular partnership focusevaluat-ed on improving the information compe-tence of management information sys-tems undergraduates. A comparison of pre- and postlibrary-instruction sur-veys showed that students developed greater confidence with course activi-ties and higher standards in research.

necessary for meeting the challenges of today’s workforce: the ability “to man-age resources, the ability to work amica-bly and productively with others, the ability to acquire and use information, the ability to master complex systems, and the ability to work with a variety of technologies” (Copple et al., 1992, pp. 3–4, 22–23).

Although we found no systematic studies on how information literacy will affect workplace productivity, in its 1998 progress report the National Forum on Information Literacy (1998) pointed out that in the information age “the workplace is going through cata-clysmic changes that very few will be prepared to participate in successfully and productively unless they are infor-mation literate” (National Forum, 1998). Cheuk (2002) further elaborated that today’s workers are expected to carry out multiple tasks by using vari-ous sources of information to make crit-ical decisions. Many American corpo-rate leaders, realizing the strong influence and demands of the informa-tion age, incorporated and implemented information literacy training to help employees translate information into knowledge to inform vital decisions. Such training, implemented at organi-zations such as Dow Chemical, Pacific Bell, and Hewlett-Packard, among oth-ers, proved that employees are more productive if they are information liter-ate. In the business world, productivity means profitability.

Public education institutions con-stantly evaluate their curricula and pro-grams to meet the needs of today’s stu-dents. In 1995, under the instruction of the Commission on Learning Resources and Instructional Technology, the Cali-fornia State University (CSU) Informa-tion Competency Work Group, which consists of librarians and teaching facul-ty members, was formed. The group stated that “the institution will have to determine competencies that students must achieve at three different stages: when they arrive at the university, early enough in their university experience, and when they graduate” (Curzon, 1995). In the final report, the group rec-ommended that information competen-cy be embedded at general education areas and by majors.

The CSU Board of Trustees approved the “Accountability Process” in 1999. They identified thirteen fundamental institutional performance areas of responsibility and defined “quality” at all program levels—baccalaureate, gradu-ate, and postbaccalaureate. The final report defined the institution’s account-ability and students’ learning outcomes, employability upon graduation, and abil-ity for lifelong learning (CSU, 2001).

Furthermore, the Association of Col-lege and Research Libraries (2000) has published “Information Literacy Stan-dards for Higher Education.” These standards were endorsed by the Ameri-can Association for Higher Education (AAHE) in spring 2000, only the sec-ond time that AAHE has endorsed a pol-icy position. The Board approved the AAHE Statement on Diversity in April, 1999 (Breivik, 2000).

The Power of the Internet

Having been exposed to computers often even before kindergarten, most students today are familiar with them and use the Internet as part of their daily lives. A recent survey (UCLA, 2003) showed that the percentage of students at school who use the Internet increased from 59.9% in 2000 to 73.7% in 2002. The percentage was as high as 97% for students between 12 and 18 years of age and 87% for those between 19 and 24.

In 1998, the Sales & Field Force Automationeditorial team surveyed 434 subscribers on their views regarding their use of the Internet. According to the survey (Tuck, 1999, p. 44), the fol-lowing percentages of subscribers listed five top reasons for using the Internet and communication services: e-mail, 91%; research, 74%; downloading soft-ware, 73%; market intelligence, 71%; and news/industry information, 68%.

Clearly, the Internet is here to stay and can be a powerful tool if used wisely. We suggest that guidelines regarding effec-tive use of the Internet generally incor-porate the following criteria in conduct-ing searches and information use:

1. Five As: authority, author, accuracy, accountability, and authenticity 2. Five Ws: what, who, why, where,

and when

Students’ Information Literacy Skills

Abell (2000), of the Record Manage-ment Society of Great Britain, defined three levels of working on information: gathering and maintaining, checking and analyzing, and using information to analyze a business. National initiatives in Australia and other industrialized countries proved that information liter-acy competency requires a national effort to keep students competitive upon graduation and beyond.

Littlejohn and Benson-Talley’s 1990 survey of CSU Long Beach business stu-dents showed that only 39% of the respondents had received formal library instruction. These researchers concluded that “not only do the students not know a great deal about business resources, they still don’t know that they don’t know—an apparent reason continues to be lack of formal instruction in the use of business resources and lack of faculty participation and support in helping stu-dents achieve a higher degree of library skills” (Littlejohn & Benson-Talley, 1990, p. 76). Four years later, Hawes (1994) undertook a literature review to investigate what business schools are currently doing and came up with a sim-ilar conclusion: “Some business schools are making some effort to teach infor-mation literacy skills . . . but still not nearly enough” (p. 76). Hawes attributed these findings to “a lack of serious atten-tion to this issue by the business school accreditation organizations.” When he contacted the director at the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Busi-ness (AACSB) in 1992 to inquire on the AACSB’s interest in information liter-acy, he was told that “it is not on a par with that on computer literacy of a few years ago” (p. 76).

This dearth of attention given to library instruction is unfortunate, partic-ularly in light of findings regarding its effectiveness. Lombardo and Miree (2003) proved that library instruction could be effective in teaching informa-tion literacy to improve library research skills of business students. Those authors found that students were more aware than before of research resources other than the World Wide Web. The sampled students’ use of preferred

resources—those typically used first to complete projects on the Web—dropped from 83.3% to 70%, and, yet, their use of library databases increased from 15.6% to 17.8%, with the most signifi-cant change being the sharp increase in use of print materials, which climbed from 1.1% to 11.1%.

“Although business professors agree that information literacy is an important goal for their students, many assume that students are already well versed in business research tools and methods” (Lombardo & Miree, 2003, p. 20). Yet, recent studies (Kraus, 2002; Roig, 1997, 1999) indicate that business students do not have adequate information literacy and library skills to perform compre-hensive research and cannot tell whether their own writing is plagiarized until their professors or librarians point this out for them. It seems that we are faced with an interesting paradox: Stu-dents today are familiar with computers even before entering kindergarten, but their information literacy and library skills are not sophisticated enough to keep up with 21st-century information demands.

The revolution and evolution of the Internet makes access to information fast, easy, and affordable. Quite often, users take this information for granted and assume that all information retrieved is accurate and complete. Information comes from a broad spectrum in various sources and formats. Oman (2001) reminded us, “One thing is certain—be sure not to equate information literacy with just the Internet! The glamour of the technology has blinded end users to the fact that information does exist in other formats and may not even be avail-able on the Web” (p. 38).

Study and Method

To better assess students’ information literacy levels and how librarian and classroom teaching faculty members can collaborate effectively to improve information literacy and library research skills, we (a management information systems professor and a librarian from San Jose State University) initiated this study in fall 2002 and administered information literacy surveys in spring 2003.

We administered pre- and posttest surveys to all students in six sections of a capstone MIS Strategy class. The cap-stone course required students to work in teams of three to conduct secondary research and write a term paper on the strategic implications of an emerging technology for an industry and a com-pany in that industry. The course includ-ed an introductory session, which lastinclud-ed an hour and 15 minutes, on resources available at the library to support research on technologies, industries, and companies. In all classes, the refer-ence librarian who specializes in MIS research taught the session. The session was structured to provide the students with an overview of the research resources available to them at the uni-versity library and with hands-on expe-rience with the use of these resources. The session included a tour of the library services available through the university Web site and an introduction to business- and technology-oriented databases such as ABI/Global, EBSCO Business Source Premier, Factiva, Safari Tech Books Online, and Standard and Poor’s. Throughout the semester,

we reiterated the importance of using reliable resources, such as those acces-sible via the university library. The ref-erence librarian who conducted the introductory session was available for student consultations at the library, by phone, via e-mail, and via online chat.

The pre- and posttest questionnaires administered to the students were iden-tical. The questionnaires included two sections pertinent to this study: (a) an assessment of the students’ knowledge of, access to, and use of business research sources and practices and (b) an assessment of students’ perceptions of self-efficacy regarding the research and writing required for developing an MIS strategy.

We used complete sets of data from 135 student respondents. The data show that the sample of students in this study’s data set varies from that of the entire student body (see Table 1). One hundred percent of the students came from the MIS department, and the data show that this set of students tended to be slightly older than the entire student body. The percentages of men and Asian Americans in the study were higher than

TABLE 1. Demographics: Total Student Body (as of Fall 2002) Versus Students Who Provided Complete Data for Both Pre- and Posttest Questionnaires

Study Student Demographic item participants bodya

Age (years) 27.51 26.2

Gender (%)

Male 68 49

Female 31 51

No answer 1

Ethnicity (%)

African American 1 4

Asian 66 42

Caucasian 13 23

Latino 5 15

Native American 0 .5

Other 10

No answer 4 15

Years in school 4.57

Major (%)

MIS 100

GPA 3.00 2.83

Hours spent per week on

Work 15.69

Nonacademic, school-related activities 3.60 Nonschool-related volunteer work 1.16

aSource:SJSU Institutional Planning and Academic Resources, Fall 2002.

the corresponding percentages in the entire student body. Conversely, there were lower percentages of Caucasians, African Americans, and Latinos in this study compared with the entire student body.

Students in our study had an average grade point average of 3.0, which is slightly higher than that of the entire stu-dent body (2.83). Stustu-dents in the study averaged 15.69 hours of work per week, 3.6 hours of nonacademic school-related activities, and 1.16 hours of nonschool-related volunteer work.

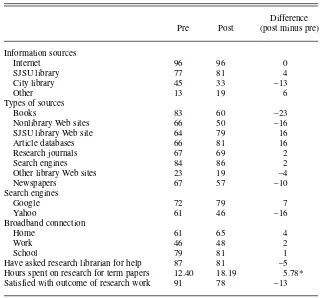

We conducted ttests on paired sam-ples for means to assess the significance of the differences between students’ pre- and posttest perceptions of the time required to complete a term paper and of their self-efficacy regarding MIS strategic analysis. We provide results of these ttests in Tables 2 and 3.

Findings

The student reports indicate that there was strong assimilation and application

of the techniques that were taught by the reference librarian and reinforced throughout the semester. The results show a shift away from city library use toward increased use of the university library between the pre- and posttest measurements (see Table 2). Students reported a 4% increase in use of the uni-versity library and a 13% decrease in use of city libraries. In contrast with the findings of Lombardo and Miree (2003), we found a shift away from the use of print material—a 23% decrease in the use of books and a 10% decrease in the use of newspapers. These findings are attributable to the fact that our stu-dents were conducting research on emerging technologies, which are cov-ered most extensively in the journals and periodicals indexed in online article databases.

In students’ use of online sources, there was a marked shift toward the rec-ommended University Library Website and Article Databases (retrievable from http://sjlibrary.org/research/databases/in dex.htm). Students reported a 16%

decrease in the use of nonlibrary Web sites and a 4% decrease in the use of other library Web sites, coupled with a 16% increase in use of the university’s library Web site and databases. Addi-tionally, there was a noticeable shift toward the reported use of the search engine Google, whose advanced fea-tures were showcased in the introduc-tory session. Google use increased by 7%, and, reflecting a shift away from use of a search engine not recommend-ed during the introductory session, Yahoo use decreased by 16%.

The most intriguing finding was a sta-tistically significant increase in the num-ber of reported hours that students expected to spend on a term paper— these hours increased from 12.4 to 18.19. Furthermore, there was a 13% decrease in the number of students reporting that they were satisfied with the results of their research efforts. These findings suggest that as the stu-dents gained greater knowledge of research sources and processes, they also developed higher standards regarding their research work. They realized that completing a term paper required more hours than they expected at the begin-ning of the semester, before they embarked on their semester-long project. The students also reported that they were less satisfied than they used to be with the products of their efforts.

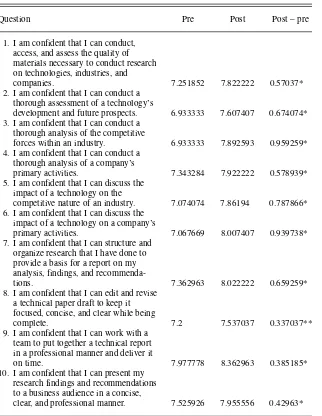

This interpretation is supported by our analysis of students’ answers re-garding their self-efficacy with strate-gic analysis. For all items, students reported greater confidence with vari-ous activities involved in strategic analysis. Of particular relevance to our interest in improving information liter-acy is the finding that students reported greater confidence in (a) their ability to assess the quality of materials that they needed to conduct their research and (b) their ability to structure and orga-nize the information collected in their research.

Conclusions

This study’s findings show that intensive interweaving of course con-tent and library instruction is an effec-tive means of improving students’ information literacy. The results show

TABLE 2. Summary of the Results of the Pre- and Posttest

Questionnaires on Research Sources and Practices, in Percentages

Difference Pre Post (post minus pre)

Information sources

Internet 96 96 0

SJSU library 77 81 4

City library 45 33 –13

Other 13 19 6

Types of sources

Books 83 60 –23

Nonlibrary Web sites 66 50 –16

SJSU library Web site 64 79 16

Article databases 66 81 16

Research journals 67 69 2

Search engines 84 86 2

Other library Web sites 23 19 –4

Newspapers 67 57 –10

Search engines

Have asked research librarian for help 87 81 –5 Hours spent on research for term papers 12.40 18.19 5.78* Satisfied with outcome of research work 91 78 –13

*Significant at the .01 level.

that this method increased students’ use of high-quality resources available to them in the library. The students’ high-er standards with respect to their research and writing is evident in their reports of lower satisfaction with their research efforts and in their increased estimates of the amount of time that they expect to spend on preparation of research papers. This finding is rein-forced by the consistent and significant improvement in students’ confidence regarding the various class activities with greatest relevance to information literacy—business research, strategic analysis, and research paper prepara-tion and presentaprepara-tion.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Malu Roldan, Department of Management Information Systems, San Jose State University, San Jose, California 95192-0244. E-mail: roldan_m@cob.sjsu.edu; and Yuhfen Diana Wu, University Library, San Jose State Uni-versity, San Jose, California 95192-0028. E-mail: Diana.Wu@sjsu.edu.

REFERENCES

Abell, A. (2000). Corporate information literacy:

An essential competence or an acquired skill, Bulletin 99. Retrieved April 16, 2001, from Record Management Society of Great Britain Web site: http://www.rms-gb.org.uk/99%20 Abell.html

Association of College and Research Libraries.

(2000). Information Literacy Competency

Stan-dards for Higher Education. Retrieved July 31,

2003, from http://www.ala.org/Content/

NavigationMenu/ACRL/Standards_and_ guidelines/Information_Literacy_Competency_ Standards_for_Higher_Education.htm#useofst Breivik, P. S. (2000). Information literacy and the

engaged campus: Giving students and commun-ity members the skills to take on (and not be taken in by) the Internet. AAHE Bulletin, 53(3), 3–6.

Cheuk, B. W. (2002). Information literacy in the

workplace context: Issues, best practices and challenges. White paper prepared for UNESCO, the U.S. National Commission on Libraries and Information Science, and the National Forum on Information Literacy, for use at the Information Literacy Meeting of Experts, Prague, the Czech Republic. Retrieved from http://www.nclis.gov/libinter/infolitconf &meet/papers/cheuk-fullpaper.pdf

Copple, C. E., Kane, M., Matheson, K., Meltzer, A. S., Packer, A., & White, T. (1992). The Sec-retary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills: SCANS in the schools. Prepared for Secretary’s Commission, U.S. Department of Labor. Washington, DC: Pelavin Associates.

CSU Board of Trustees. (2001, February). The

CSU accountability process. Retrieved July 31, 2003, from California State University Chan-cellor Office Web site: http://www.calstate. edu/Cornerstones/reports/ProAcctProcess.html

Curzon, S. C. (1995, December). Information

competence in the CSU: A report submitted to the Commission on Learning Resources and Instructional Technology Work Group on Infor-mation Competence, CLRIT Task 6.1. Retrieved August 1, 2003, from http://www.calstate.edu/ LS/Archive/info_comp_report.shtml

Davis, S., & Botkin, J. (1994). The coming of

knowledge-based business. Harvard Business

Review, 72(5), 165–170.

Drucker, P. F. (1995). The information executives

truly need. Harvard Business Review, 73(1),

54–62.

Hawes, D. K. (1994). Information literacy and the

business schools. Journal of Education for

Business, 70(1), 54–61.

Kraus, J. (2002). Rethinking plagiarism: What our

students are telling us when they cheat. Issues

in Writing, 13(1), 80–95.

Littlejohn, A. C., & Benson-Talley, L. (1990). Business students and the academic library: A

second look. Journal of Business & Finance

Librarianship, 1(1), 65–88.

Lombardo, S. V., & Miree, C. E. (2003). Caught in the Web: The impact of library instruction on business students’ perceptions and use of print

and online resources. College & Research

Libraries, 64(1), 6–22.

National Forum on Information Literacy. (1998,

March). A progress report on information

liter-acy: An update on the American Literacy Asso-ciation Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final report. Retrieved September 20, 2003, from http://www.infolit.org/documents/ progress.html

Oman, J. (2001). Information literacy in the

work-place. Information Outlook, 5(6), 33–43.

Roig, M. (1997). Can undergraduate students determine whether text has been plagiarized?

Psychological Reports, 47,113–122.

Tuck, L. (1999, February). 1998 Sales & Field Force Automation Reader Survey Part 2: The

Internet. Sales & Field Force Automation,

40–46.

UCLA Center for Communication Policy. (2003,

February). The UCLA Internet Report:

Survey-ing the digital future, year three. Retrieved August 1, 2003, from http://www.ccp.ucla.edu

TABLE 3. Comparison of Pre- and Posttest Student-Reported Self-Efficacy With Strategic Analysis

Question Pre Post Post – pre

1. I am confident that I can conduct, access, and assess the quality of materials necessary to conduct research on technologies, industries, and

companies. 7.251852 7.822222 0.57037* 2. I am confident that I can conduct a

thorough assessment of a technology’s

development and future prospects. 6.933333 7.607407 0.674074* 3. I am confident that I can conduct a

thorough analysis of the competitive

forces within an industry. 6.933333 7.892593 0.959259* 4. I am confident that I can conduct a

thorough analysis of a company’s

primary activities. 7.343284 7.922222 0.578939* 5. I am confident that I can discuss the

impact of a technology on the

competitive nature of an industry. 7.074074 7.86194 0.787866* 6. I am confident that I can discuss the

impact of a technology on a company’s

primary activities. 7.067669 8.007407 0.939738* 7. I am confident that I can structure and

organize research that I have done to provide a basis for a report on my analysis, findings, and

recommenda-tions. 7.362963 8.022222 0.659259* 8. I am confident that I can edit and revise

a technical paper draft to keep it focused, concise, and clear while being

complete. 7.2 7.537037 0.337037**

9. I am confident that I can work with a team to put together a technical report in a professional manner and deliver it

on time. 7.977778 8.362963 0.385185* 10. I am confident that I can present my

research findings and recommendations to a business audience in a concise,

clear, and professional manner. 7.525926 7.955556 0.42963*

*Significant at the .01 level. **Significant at the .05 level.