A DISCOURSE-GROUNDED APPROACH TO IMPROVING STUDENT WRITING

A Thesis Presented to

The Faculty of the Department of Linguistics

Northeastern Illinois University

In Partial Fulfillment

Of the Requirements for the Degree

Master of Arts

In Linguistics

iii Abstract

This thesis integrates insights from linguistics and rhetoric/ composition studies to

create and test the effectiveness of a writing guide, designed for independent use by

composition students, that is aimed at improving the global text quality of argumentative

essays by helping students consider the “rhetorical situation” (Bitzer 1968) as a

communicative context that motivates the deployment of features of well-formed written

discourse (Berman 2008). The guide attempts to make pedagogical use of Berman’s

descriptive framework of facets of discourse—global level principles, categories of

referential content […] and overall discourse stance” which stem from a large scale

cross-linguistic research project on the development of discourse abilities (Berman 2008:

735). The student writing guide, created by building this discourse framework upon the

groundwork of rhetoric and composition theory, was tested for its effectiveness to

improve drafts of writing by using online data collection methods.

A group of advanced-placed ELL students wrote first drafts of argumentative

essays. After reading and understanding the writing guide, participants then used it to

write second drafts by revising their first drafts. Quantitative and qualitative data were

analyzed to ascertain the extent to which the second drafts showed improvement in global

text quality. While most of the second drafts showed little change in their levels of global

text quality, all of the revised drafts indicated an increase in the usage of discourse

features involved in global text quality and rhetorical effectiveness. Despite minor

difficulties participants had with some the content of the guide, participants overall

understood and were able to use the writing guide to revise their drafts and imagine a

iv

Acknowledgements

I would like to express the sincerest gratitude to the faculty of the department of

Linguistics at Northeastern Illinois University, particularly to Dr. Shahrzad Mahootian,

my graduate thesis advisor, as well as to thesis committee members Dr. Judith

Kaplan-Weinger and Dr. Lewis Gebhardt, for the invaluable direction, instruction, and inspiration

they have provided, not only for the completion of this thesis, but also for a substantial

amount of my academic and professional formation. Dr. Bridget O’Rourke, of the

department of English at Elmhurst College, who sparked my interest in composition

studies, allowed me to collaborate with her in composition research and pedagogy, and

sponsored my first conference presentation on composition, is acknowledged with the

most heartfelt appreciation for how she mentored, supported, and believed in me. My

enthusiastic, supportive, and good-humored wife, Mercy Turner, who has borne with me

through the innumerable hours of the preparation of this manuscript, was an invaluable

source of encouragement. The highest gratitude is ultimately and exceedingly directed to

God, who not only gave me life, breath and time to complete the present work, but also

v

Table of contents

ABSTRACT ... III

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... V

LIST OF TABLES ... VII

1.INTRODUCTION:COMPOSITION THEORY, LINGUISTICS, AND IMPROVING STUDENT WRITING ... 1

2.REVIEW OF APPROACHES IN COMPOSITION STUDIES ... 6

2.1THE COGNITIVIST APPROACH ... 7

2.2THE EXPRESSIONIST APPROACH ... 9

2.3THE SOCIAL-EPISTEMIC APPROACH ... 10

2.4MULTICULTURALISM, THE CONTACT ZONE, AND BAKHTIN’S HETEROGENEITY OF VOICES.12 2.5THE CONTEXT OF WRITTEN DISCOURSE:THE RHETORICAL SITUATION ... 15

1.EXIGENCE:THE OCCASION AND MOTIVATION FOR SPEAKING/WRITING ... 18

2.AUDIENCE:WHO ARE YOU SPEAKING-WRITING TO? ... 20

3.SPEAKER-WRITER:WHAT ARE YOUR ROLES, IDENTITIES, VOICES, AND ATTITUDES? ... 27

2.6BERMAN AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF DISCOURSE ... 30

2.7DISCOURSE STANCE, REFERENTIAL CONTENT, AND GLOBAL TEXT ORGANIZATION ... 33

1.GLOBAL TEXT ORGANIZATION:TOP-DOWN (EXPOSITORY)/ BOTTOM-UP (NARRATIVE) ... 34

2.CATEGORIES OF REFERENTIAL CONTENT ... 39

3.DISCOURSE STANCE: ORIENTATION, ATTITUDE, GENERALITY ... 41

3.METHODOLOGY ... 46

3.1CREATING A STUDENT WRITING GUIDE: STRUCTURE, AIMS, AND INTENDED USE ... 46

vi

2.SWG,INTRODUCTION AND RECAP ... 49

3.SWGPARTS 1-3, OCCASION, AUDIENCE, AND SPEAKER-VOICE ... 50

4.SWGPARTS 4-5, INFORMATION UNITS, AND STRUCTURE/ OVERALL ORGANIZATION ... 52

3.2PARTICIPANTS IN THE STUDY ... 52

3.3DATA COLLECTION ... 54

1.STEP 1:WRITING A FIRST DRAFT OF AN ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY ... 54

2.STEP 2:READING THE SWG AND FILLING OUT THE FIRST QUESTIONNAIRE ... 55

3.STEP 3:(RE)WRITING A SECOND DRAFT AND FILLING OUT THE SECOND QUESTIONNAIRE 56 3.4DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS: THE EFFECT OF THE SWG ON REVISION OF DRAFTS ... 57

1.A QUANTITATIVE ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK AND QUALITATIVE MEASUREMENTS ... 57

2.DETERMINING THE PRESENCE AND NUMBER OF THE NINE FEATURES ... 58

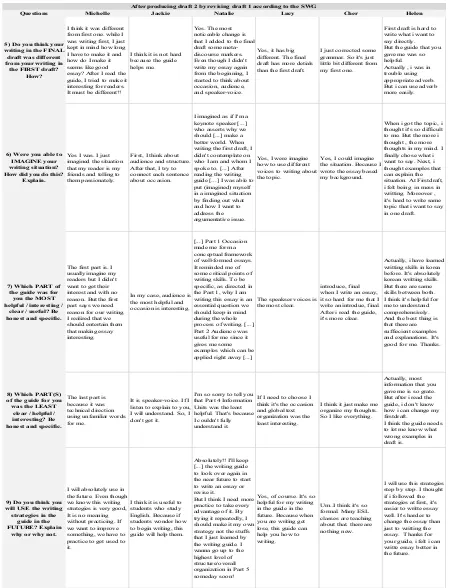

3.DETERMINING THE PARTICIPANTS’ ATTITUDE TOWARD THE SWG AND REVISION ... 65

4.FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION ... 68

5.OUTLOOK FOR FUTURE STUDIES ... 74

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 75

APPENDIX I:THE STUDENT WRITING GUIDE ... 79

APPENDIX II:ANNOTATED DRAFTS AND UNABRIDGED QUESTIONNAIRE RESPONSES ... 101

APPENDIX III:SCREENSHOTS OF THE ONLINE RESOURCES INVOLVED IN THE STUDY ... 115

vii List of tables

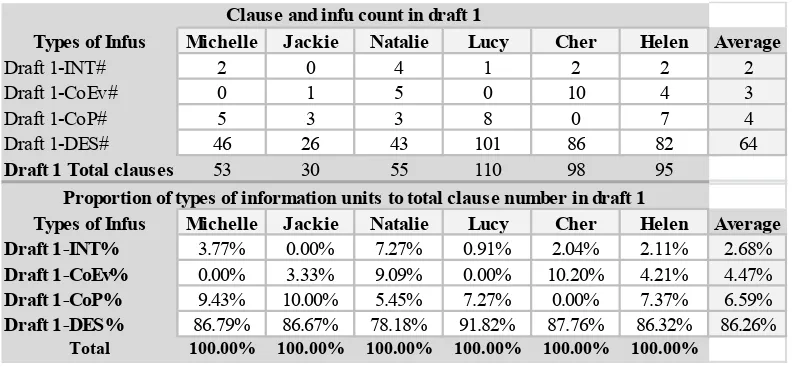

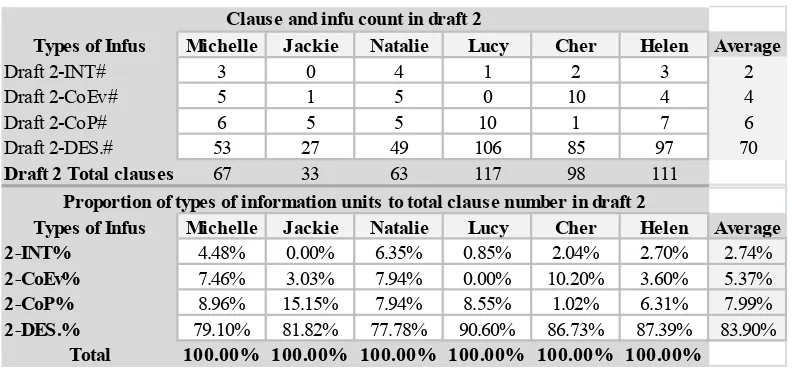

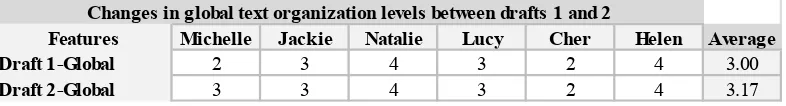

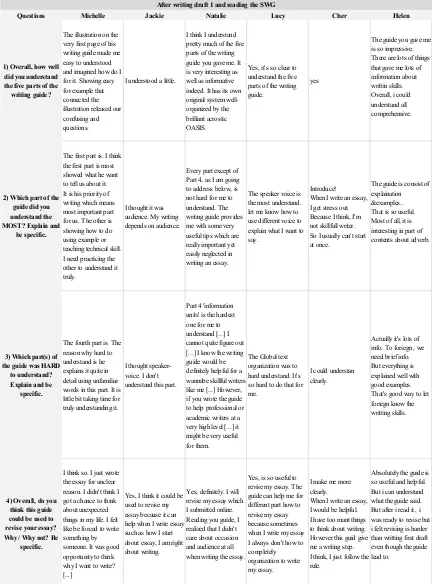

TABLEI:INFORMATION UNITS IN DRAFT 1 ... 59 TABLEII:INFORMATION UNITS IN DRAFT 1 ... 60 TABLEIII:DISCOURSE FEATURES IN DRAFTS 1-2 ... 61 TABLEIV:PERCENTAGE OF INCREASE OF DISCOURSE FEATURES FROM DRAFT 1 TO DRAFT 2 ... 64 TABLEV:LEVELS OF GLOBAL TEXT QUALITY IN DRAFTS 1-2 ... 64 TABLEVI:PARTICIPANTS’ RESPONSES TO QUESTIONNAIRE 1 ... 66 TABLEVII:PARTICIPANTS’ RESPONSES TO QUESTIONNAIRE 2 ... 67

1. Introduction: Composition theory, linguistics, and improving student writing

This thesis, in integrating theory from rhetoric/composition and linguistics,

attempts to merge insights from two fields that, surprisingly, are not often intermingled.

A field that is devoted to the study of written communication ought to be closely

associated with a field that attempts to answer the most fundamental questions about the

forms and functions of human language. Granted, it seems that the fields of linguistics

and composition have been gradually benefiting mutually from one another, as evident by

the creation of Linguistics, Composition and Rhetoric departments in some universities,

but composition studies and linguistics have often been in “complementary distribution,”

as it were, in the literature. This was not always the situation, Faigley (1989) points out,

as “in earlier decades of the CCCC” (the major conference for composition studies),

linguists had been seriously involved in composition studies, and that, “in the 1950s,

linguists published articles frequently in CCC and held major offices in the organization”

(1989: 241). “In the 1960s,” Faigley continues, “when rhetoric and composition

blossomed as a discipline, [some] saw English teachers' awareness of linguistics as the

most important development of the first two decades of the CCCC, and [others] proposed

linguistics as the basis of a modern theory of rhetoric” causing the 1960’s to be known as

“the decade of language study and rhetorical theory” (1989: 241).

However, the 1970’s saw a gradual decline of linguists working in the field of

composition and rhetoric that was attributable to a movement in the social sciences called

the cognitive turn. The cognitive turn took shape in composition studies in the form of a

new approach to writing—process theory—that re-envisioned writing as a structured

the 1970s became the decade of process theory so that by “1980 studies of writers'

processes had clearly become ascendant over studies of writers' language” (1989: 241).

Moreover, “language studies declined in importance” because of a linguistic turn in the

field of linguistics, spawned by Chomsky’s theory of generative grammar, which

diverged from the then dominant linguistic approaches in both aims and assumptions

(1989: 241). Faigley recounts how the linguistic turn saw linguists re-prioritizing the

formal aspects of language over and above the pedagogical, rhetorical and literary aspects

of language:

“Chomsky's theory of transformational-generative grammar influenced the study of language in North America as no other theory had in the past […] Language could be orderly only if it were idealized. If actual language was used as data, the orderliness of language predicted by generative grammar soon disintegrated. Chomsky insisted that language be viewed as abstract, formal, intuitive, and acontextual. His goal for a theory of language was describing a human's innate capacity for language, not how people actually use language. When asked what relevance the study of linguistics had for education, Chomsky answered

absolutely none. Gradually, those interested in studying discourse came to heed Chomsky's warnings” (1989: 241-42).

Chomsky’s influence, Faigley suggests, was detrimental for those wishing to study

discourse as it “accelerated the formation and growth of separate linguistics departments

committed to the theoretical study of formal structure in language,” and up until now,

theoretical linguists “have tended to dismiss as ‘uninteresting’ any applied questions

about language, such as the educational implications of language theory,” asking only

“‘interesting’ questions about abstract universals underlying language” (1989: 242).

Faigley speculates that “had Chomsky's influence been restricted to language theory,

admitting, however, that “to blame Chomsky, […] for the decline of linguistics within

compositions studies is not merely simplistic; it is wrong” (1989: 242).

Constructing a student writing guide grounded in findings on discourse

development and built upon the foundation of principles of rhetoric/composition

demonstrates how linguistics and composition theory can work harmoniously in concert.

Linguistic findings on discourse and rhetoric/ composition theories can be mutually

forged into a pedagogically-aimed tool to address the difficulties developing

student-writers face when they sit down to write. To bring together insights from both of these

fields in a useful way, constructing a guide for developing student-writers, is covertly

aimed at satisfying this stark lacuna that demands filling.

Another aim underlying this thesis is to give writing-students a perspective and a

grasp on their own written communication that traditional composition pedagogy has

often denied them. Composition is a difficult exercise because it is “a highly abstract

cognitive process” and an awkward communicative exercise because communication

across the medium of paper seems to be heavily decontextualized from the rhetorical

situation, stripped of the components that usually accompany real-life communication

(Cheng & Steffensen 1996: 150). The challenge of composition may lie in the fact that

discourse abstracted away form the contexts that gave it birth is less-readily meaningful

and coherent to its speaker-writers. A piece of notebook paper, the screen of a computer,

or whatever other silent medium a writer happens to use, de-contextualizes the

communicative moves that student writers are one the one hand used to deploying in real

communicative (social) contexts, but on the other hand must now make in an artificial,

real-life exigence (occasion) that usually gives it birth. The argumentation engaged in by

able-students in public contexts, among colleagues, must, in composition, take place on a

piece of paper. When “we hear naturally spoken language […] the music of prosody

enacts some of the meaning so that we ‘hear’ it […] as though the meaning comes to us

rather than us having to go after it” (Elbow 2006: 643). Audibility, which “tends to draw

[an audience] into and through the words, increasing our experience of energy,” is often

stripped away during the writing process (Elbow 2006: 643). This lack of audible,

real-life context in writing diminishes the communicative energy that is so essential to verbal

thought, creating roadblocks for students in the brainstorming and composing process.

Despite the good intentions of many teachers of composition, traditional writing

pedagogy seems often to stifle rather than to evoke the kind of dialogue that fosters a

sense of the rhetorical situation used in writing. It seems that much of traditional writing

pedagogy has not helped student-writers breathe communicative energy from real-life

social contexts back into their writing.

Cheng & Steffensen (1996) aptly point out that many students of writing are often

unable to consider a rhetorical audience in their writing because “most composition

classrooms” fail “to develop into forums or discourse communities” which can “evoke a

sense of audience in student writers” (1996: 152). Writing without consideration of the

rhetorical situation results in a kind of artificial discourse produced in response to no

other exigence, or set of motivating factors, than to produce a written product for the sake

of producing a written product. This kind of artificial discourse is aimed at and motivated

by satisfying the demands of a writing teacher. Bartholomae (1985) calls such discourse a

with academic tasks by developing a knowledge-telling strategy [that] undermines

educational efforts to extend the variety of discourse schemata available to students”

(1985: 633).

Part of the solution to this problem may lie in the use of the imagination to

compensate for the absence of the audibility of real discourse contexts, to essentially

re-imagine a rhetorical or discourse situation, to breathe context back into (re-inspire)

student writing. The artificiality that characterizes many developing writers’ essays

seems to be largely due to a lack of a sense of context that their written discourse ought to

be couched in: the situation out of which their writing ought to flow and to which their

writing ought to respond. Therefore, the final aim of this thesis it to produce and test a

student writing guide to help students re-imagine a discourse (writing) situation and to

deploy facets of well-formed discourse toward the (imagined) communicative ends in

their (imagined) writing situations. After constructing the SWG by integrating insight

from rhetoric/ composition studies and findings from empirical research on the

development of well-formed discourse, the SWG will be assessed for its effect on drafts

of argumentative essays that student-writers used to revise them.

In the following sections, I first provide a review of literature (section 2) in which

I outline major trends in the field of composition studies (2.1-2.3), highlight relevant

background material from literary and rhetorical studies (2.4-2.5), and then review

findings from Berman’s cross-linguistic research about the development of discourse,

focusing on three of Berman’s five facets of discourse development (2.6-2.7). The review

composition students or advanced English language learners in the production of

well-formed expository text (argumentative essays). In section 3, methodology, I discuss the

structure and intended uses of the SWG and explain the reasons for the form it takes.

Information about the subjects who participated in the study and the steps involved in

assessing the efficacy of the SWG are also outlined. Finally, in section 4, I discuss my

findings and, in section 5, I present my ideas for future research in this area.

2. Review of approaches in composition studies

The field of rhetoric/composition studies (or, simply composition studies) is

represented by teachers and theorists who seek to study, contribute to, and enhance the

theory and practice of writing pedagogy and whose articles often appear in journals such

as College Composition and Communication and College English. Composition

studies is a highly interdisciplinary and theoretically diverse field comprised of scholars

who often represent views of writing theory and pedagogy that are based on varying

epistemologies and ideologies. To characterize this, Berlin (1988) reviewed three major,

differing approaches to composition and writing pedagogy in composition studies,

pointing out that “a way of teaching is never innocent [and] pedagogy is imbricated in

ideology, in a set of tacit assumptions about what is real, what is good, what is possible,

and how power ought to be distributed” (492). For Berlin, no discourse or practice is free

from ideology. Van Dijk’s socio-cognitive definition of ideology seems to be the most

illustrative:

“[ideologies are] basic frameworks of social cognition, shared by members of social groups, constituted by relevant selections of sociocultural values, and organized by an ideological schema that represents the self-definition of a group [that sustain] the interests of groups [and] have the cognitive function of

indirectly monitor the group-related social practices, and hence also the text and talk of members” (van Dijk, 1995: 248).

If ideology is inscribed deeply on the way composition scholars/teachers approach their

object of inquiry, then ways of teaching—including the text and talk used to deploy

teaching methods—apparently are trapped, as it were, in an inescapable ideological

circle. Certainly, even a cursory glance at the literature shows fierce, seemingly

unresolvable debates in composition studies, which rage in public discourse; one

particular instance of this is as a several-year long debate that took place about politics in

the writing classroom that intensified to the point of professional friendships becoming

"dissolved in the heat of the argument," as Hariston put it (1993: 255). The underlying

ideologies that composition teachers and theorists subscribe to are clearly a matter of

great consequence.

What follows is a brief review of three major perspectives in composition

studies—cognitive, expressionist, and social-epistemic approaches—that represent

different ideologies and epistemologies. In addition to these perspectives, the concept of

multi-voicedness, which has important applications in writing pedagogy, will be

discussed. Then, I discuss literature pertaining to the “rhetorical situation,” which

characterizes the context of written discourse. Finally, I review three of Berman’s (2008)

five facets of discourse production, focusing on features of well-formed discourse which

will later be integrated into the SWG.

2.1 The cognitivist approach

A cognitivist approach, recognized by many as the most traditional approach, is

views truth as objective, unambiguously knowable, and communicable from person to

person (Berlin 1988: 488). The well-known “process over product” idea that urges

writing pedagogy to address the writing process rather than the written product was

promoted most vocally by (but did not originate with) the cognitivists, such as Flower &

Hayes (1981), who viewed the writing process

“as a set of distinctive thinking processes which writers orchestrate or organize during the act of composing [and which] have a hierarchical, highly embedded organization in which any given process can be embedded within any other” (Flower & Hayes 1981: 366).

Cognitive rhetoric, therefore, brakes up the writing process into discrete, identifiable and

logical steps in the sequence of pre-writing (planning), writing (translating), and

rewriting (reviewing). A key assumption that cognitivists hold is that universal laws that

underlie the writing process are discoverable; that the “features of composing” are

analyzable “into discrete units” expressible in “linear, hierarchical terms;” and that a

writer’s mind is like a computer processor that moves logically through operations in

order to generate writing; and that each step of the writing process creates “a hierarchical

network of goals [which] in turn guide the writing process” (Berlin 1988: 481-82,

Faigley 1986: 533).

Thus, writing pedagogy with a cognitivist bent would not only stress mastery of

form, convention, and logical arrangement of the content of a written work, but would

also stress competence in a sequenced writing process—prewriting, writing, and

rewriting. Students might be measured against explicit, pre-set standards of each step in

include brainstorming material and first drafts to be turned in along with final drafts in

order to assess a student’s writing process.

2.2 The expressionist approach

An expressionist approach draws from a Platonic epistemology that sees truth and

reality as knowable only subjectively; that is, in order to know, the thinker must know

him- or herself. Since it is not possible to know objectively, knowledge is therefore not

communicable from person to person. Berlin (1988) notes that the psychology of

Rousseau, which considers the individual as inherently good, and the literary movement

of romanticism, are major resources for expressionist thought, which recoils from “the

urban horrors created by nineteenth century capitalism,” while promoting nature,

emotionalism, and the imagination as preeminent over rationality and modern civilization

(Berlin 1988: 484). He traces the roots of expressionist rhetoric to a reaction against the

“elitist rhetoric of liberal culture” whose scheme argued “for writing as a gift of genius,

an art accessible only to a few” (484). In expressionist rhetoric, writing is an inherent

ability of all people. This proposition is at the heart of Elbow's book of writing theory,

entitled “Everyone can write” (2000). Berlin notes that expressionists like Elbow would

view writing as a creative, artistic “paradigmatic instance” of “locating the individual’s

authentic nature” or discovering one’s true self, and drawing upon the “reality of the

material, the social, and the linguistic […] insofar as they serve the needs of the

individual” (Berlin 1988: 484).

Expressionism has been no stranger to writing pedagogy. Berlin (1988) observes

number of colleges and universities” and is “openly opposed to establishment practices”

that are hegemonic and homogenizing (1988: 487). In writing pedagogy with an

expressionist bent, instructors might lay down a few guiding writing conventions, but

largely get out of the way while students express themselves in their own unique creative

processes. Teachers might encourage students to find their true, inner selves through

writing. Indeed, the writing process is framed as a journey into the self in order to unearth

one’s position on topics and to express one’s own self-aspirations. Convention and form,

as well as error analysis, might well be secondary concerns in a more expressionistic

writing class.

2.3 The social-epistemic approach

Social-Epistemic rhetoric holds that the material world, knowledge, communities,

and even selves are all socially constructed. A wide range of scholars, such as Bruffee,

Faigley, Trimbur and Bizzel are associated with social-epistemic rhetoric (or social

constructionism). Among social-constructionists, Berlin points out, there are “as many

conflicts […] as there are harmonies [but that they] share a notion of rhetoric as a

political act involving a dialectical interaction engaging the material, the social, and the

individual writer, with language as the agency of mediation” (1988: 488). Knowledge is a

social construct, a product of a dialectical interaction between the individual, the

discourse community, and the material conditions the individual exists in, which implies

that knowledge and (versions of) reality are continually negotiable. Language

constructs/distributes versions of external reality but is itself constructed by the

language-using “observer, the discourse community, and the material conditions of existence

constructed socially, linguistically engendered by the linguistically-confined interplay

between the “individual, the community, and the material world” implying that there are

no coherent, unique individuals, but rather, all selves are products of historical and

cultural moments and—although individuals have independent agency—their freedom is

limited insofar as the ways of conformity and dissent are pre-circumscribed by socially

constructed categories (Berlin 1988: 489). For social-constructionists, therefore,

experience is prescribed by “socially-devised definitions [and] by the community in

which the subject lives”—resulting in an all-enveloping “hermeneutic circle” that limits

the possibilities of how we can even interpret the world so that no perception is free from

self-interest and ideology (Berlin 1988: 489).

Naturally, social-epistemic rhetoric would be the most difficult to implement in

the classroom because it “attempts to place the question of ideology at the center of the

teaching of writing,” offering “both a detailed analysis of dehumanizing social experience

and a self-critical and overtly historicized alternative based on democratic practices in the

economic, social, political, and cultural spheres” (Berlin 1989: 491). In social-epistemic

rhetoric, students “must be taught to identify the ways in which control over their own

lives has been denied them, and denied in such a way that they have blamed themselves

for their powerlessness” (Berlin 1989: 490). In such a classroom, students would be

encouraged to engage in critical discourse about the established social structure and to

explore the ways in which hegemonic powers has imposed itself on them and has shaped

their identity and mindsets. Instructors would engage in liberator pedagogy, to invoke

to imprison and atomize each of them in a pre-shaped epistemology that is aimed at

sustaining its economic-industrial interests.

2.4 Multiculturalism, the contact zone, and Bakhtin’s heterogeneity of voices

As Edelstein (2005) suggests, social-constructionism has also led to a revolution

in literary studies called multicultural studies—a set of critical theories that rethinks the

“Other,” the marginalized, and the oppressed and that serves as a critique of

assimilationist discourse. This literary movement (with its off-branching Postcolonial

studies) came into being largely through the political movements of the 1950s and the

subsequent civil rights movements of the late 1960s and early 70s which called for the

end of the Vietnam War and the inclusion of Ethnic and Women’s studies in universities

(Edelstein 2005: 19). In literary studies, multiculturalism promotes “an awareness of the

otherness of the self to itself […] that we are all both someone’s other and ‘strangers to

ourselves,’” an awareness that can “positively transform our relations to ‘others’”

(Kristeva 1991, in Edelstein 2005: 35). A theory that seems to have had great influence in

composition studies, and that emerged form multiculturalism, is Pratt’s (1991) notion of

the contact zone.

The concept of a contact zone theoretically captures instances of contact between

and among selves, communities, and cultures—and the conflicting values, assumptions,

and ideology that language users bring to a text. Pratt (1991) coined the term contact zone

in thinking about the “social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each

other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism,

33-40). Writing that comes out of contact zones, according to Pratt, can be both perilous,

and artistic (1991: 4). In contact situations where one ideology is imposed on another, the

perils of writing in the contact zone could be “miscomprehension, incomprehension, dead

letters, unread masterpieces, [and] absolute heterogeneity of meaning,” whereas in

situations where different cultures grapple but are equal in power, artistic production can

result, such as “Autoethnography, transculturation, critique, collaboration, bilingualism,

mediation, parody, denunciation, imaginary dialogue, [and] vernacular expression ” (Pratt

1991: 4).

The concept of the contact zone is also extendible to the individual consciousness,

where the very self is the site of conflict. Multiculturalism’s revision of theother as being

located within oneself means that the self can be a stranger to oneself. A person’s inner

life could be seen as a contact zone between competing selves—perhaps a struggle

between the three categories of selves from identity studies: the interactional, relational,

and communal selves—or between nationalized or imagined selves. Following this view,

the inner self becomes, in essence, “a heterogeneity of voices,” illuminating Bakhtin

(1981) and Vygotsky’s (1962) views of the dialogic nature of the mind. Bakhtin (1981)

holds that language in the speaker-writer’s mind is a polyphony of competing voices so

that for "any individual consciousness living in it […] language is not an abstract system

of normative forms but rather […] language for the speaker exists in the form of

particular utterances from particular others”—that is, inner verbal thought is constituted

by a “plurality of languages” (1981: 293, in Trimbur 1987: 219). Language is not “a

unified abstraction [but] an ideological field, a social horizon, a struggle of voices”

a party, a particular work, a particular person, a generation, an age group, the day and

hour” and each word “tastes of the context and contexts in which it has lived its socially

charged life" (1981: 293, in Trimbur 1987: 219). Our choice of words in a composition,

therefore, are never neutral in force, but are laden with meanings and associations that

our inner voice ascribes to them and are, as Bakhtin says, "permeated with intentions”

that carry the residual “aspirations and evaluations” of the others who spoke them

(Todorov 1984: 202; cited in Trimbur 1987: 219). A single, unified authentic voice

becomes so difficult to identify, that writing entails searching for the writer “within the

social network these voices compose” and negotiating the “conflicting claims these

voices make in the writer's inner speech” (1987: 219). Producing written discourse,

therefore, is not an individual effort, but an appropriation of all of the past and present

discourses that make up a writer’s consciousness, and engaging with and responding to

that world of discourse (Bakhtin 1981: 354-55).

Trimbur makes an application along these lines to composition, pointing out that

“the language of inner speech condenses and internalizes the language of our

conversations and relations with others” so that “the outer world of public discourse has

already entered as a constitutive element into the inner world of verbal thought” (Trimbur

1987: 215). Verbal thought that generates writing is internalized social experience and

constitutes “the language of inner speech” which is “saturated with sense [and] the sum

of all the psychological events aroused in our consciousness by the word” (Vygotsky

1962: 146, in Trimbur 1987: 217). The thoughts that eventually get transferred to paper,

therefore, are others’ voices that we have gleaned from social experience that coalesce

experience as private thought are in fact constituted through the voices of others that echo

in our verbal thought” (Trimbur, 1987: 217). Language is, therefore, already and

simultaneously inside (the imagination) and outside its users, “so that there can be no

distinction between private thought and public discourse” (1987: 219). Trimbur

concludes that the goal of the writing process should no longer be considered merely as

producing discourse (as cognitivists might say), for discourse already exists as the

writer’s inner verbal thought. Internalized discourse is the raw material, as it were, out of

which writers must “forge a voice and way of speaking from the conflicting social forces

and the polyphony of voices that converge in their mental experience [and] individuate

their verbal thought and expression” (1987: 220).

2.5 The context of written discourse: The rhetorical situation

Now that perspectives from composition and literary studies have been outlined,

relevant background material on the situation or context of (written) discourse will be

provided. The rhetorical situation is assumed to be the gene pool, as it were, for the

written composition that grows out of it. It seems useful to think in terms of a

communicative situation (context) in which communicative functions (ends) are achieved

by means of linguistic forms (means). The emphasis on communicative function I take is

positioned in the assumption that traditional writing pedagogy has largely stripped

student writing of its natural context by emphasizing conventions and forms aimed at

fabricating written products, while leaving out clear emphases on the communicative

functions of those forms. Therefore, I will outline what I take to be the context of written

discourse is driven more by the rhetorical situation or whether linguistic forms

themselves engender discourse (Flower & Hayes: 1981).

Composition theorists seem to largely agree that Bitzer’s (1968) definition of “the

rhetorical situation” is an appropriate departure point for discussion of the context of

discourse. Bitzer’s definition of the rhetorical situation as the necessary and sufficient

condition for discourse has been widely discussed in rhetoric and composition studies

(Gorrell 1997: 395). Bitzer wanted to define and characterize “the nature of those

contexts in which speakers or writers create rhetorical discourse,” and elaborate on its

components (1968: 1). It was his view that discourse does not give existence to its

situation, but rather, that “it is the situation which calls discourse into existence,”

discourse being a response to the situation (1968: 2). “Rhetorical situation” says Bitzer, is

“the very ground of rhetorical activity,” “a natural context of persons, events, objects,

relations, and an exigence which strongly invites utterance” and which amounts to “an

imperative stimulus” (1968: 5). The “three constituents of any rhetorical situation” that

Bitzer posited, are 1) an exigence, “an imperfection marked by urgency”—say, a problem

needing addressing—that motivates discourse, 2) an audience, “persons who function as

the mediators of [positive] change,” real or imagined, and 3) a set of constraints, “made

up of persons, events, objects, and relations which are parts of the situation because they

have the power to constrain decision and action needed to modify the exigence,” say, for

instance, the speaker-writer’s character, logical argument, and style (1968: 6-8).

My own model of the rhetorical situation takes Bitzer’s configuration as a

excluding “constraints” which “are the hardest of the rhetorical situation components to

define neatly because they can include so many different things” (1997: 272). For me,

therefore, the rhetorical situation includes 1) exigence, the motivating factor(s) of the

discourse, 2) hearer/audience, imagined or real, intended or unintended receptors of the

discourse, and 3) speaker-writer, the person(s) who, with authorial voice, presents the

discourse to the audience in response to the exigence. I will describe each of these

components in more detail, following Grant-Davie and, where appropriate, substantiating

each component with perspectives from influential composition theorists.

The student writing guide (SWG) must help students see the significance of the

context and situation that drives and motivates written discourse before plunging them

into analysis and production of the linguistic features of a well-formed text. That is,

writing needs to be re-characterized as communicative functions (ends) deployed by the

use of linguistic forms (means). It is no longer sufficient to speak only in terms of the

written product and the linguistic forms that comprise it. Much less is it appropriate to

reduce the writing process to an act that merely meets the goals that a writing instructor

prescribes. Rather, the act of producing written discourse is reconsidered as a reflex, a

natural outflow of a writing situation. This means that a large part of students’ writing

process involves re-imagining the writing situation of their text-in-process—not as an

assignment that must be written for a teacher—but as a(n) (imagined) set of discourse

moves that meets the ends of an imagined writing situation comprised of the exigence,

1. Exigence: The occasion and motivation for speaking/writing

Exigence is “the matter and motivation of the discourse,” the speaker-writer’s

sense “that a situation both calls for discourse and might be resolved by discourse”

(Grant-Davie, 1997: 266). According to Grant-Davie, the exigence of a discourse is

addressed by considering 1) what the discourse is about, 2) why the discourse is needed,

and 3) what the discourse should accomplish. These three considerations represent, for

Grant-Davie, a more comprehensive undertaking of discourse exigence than by solely

asking why the discourse is needed, as Bitzer (1968) does.

a. What the discourse is about

Going beyond simply asking what the topic of the discourse is, Grant-Davie

advocates a more comprehensive frame by asking what underlying fundamental issues

the topic of the discourse represents—what “larger issues, values, or principles” are

involved or at stake that “motivate people and can be invoked to lead audiences in certain

directions on more specific topics” (267). Therefore, the exigence of discourse involves

what more fundamental issues are at the heart of the specific topic being discussed—what

implications the topic being discussed has for larger, fundamental issues, sets of social

values, and so on. In other words, the exigence of discourse involves considering what

deeper, underlying issue does the obvious, superficial topic instantiate.

b. Why the discourse is needed

Exigence also considers why the discourse is needed, what prompted the

discourse at the time it was written/spoken; what caused it and why at that time, which

evokes the notion of kairos, the optimal time-conditions or finest hour to speak/write.

letter, for example, may be a reply to another letter or a response to a recent event. The

question of the value of the discourse, or of why the speaking/writing matters, is also

involved in exigence. In other words, how important are the issues and why do they need

urgent addressing? The issues may be “intrinsically important, perhaps for moral

reasons,” or the issues’ significance may lie in the implications they have for the

situation, in what potential consequences may transpire if action is not taken (1997: 268).

c. What the discourse is trying to accomplish

The exigence of discourse also involves the goals or outcomes of the

speaking/writing, e.g, how the audience should react to the discourse. Grant-Davie

includes “objectives as part of the exigence for a discourse because resolving the

exigence provides powerful motivation for the” speaker-writer (1997: 269). The

objectives of a text may be aimed at persuading an audience about one of the many topics

or components a larger issue may have, so that discourse can have multiple, hierarchical,

objectives at once. Grant-Davie gives an example of a presidential candidate’s speech

aimed (immediately) at rebutting the accusations of an opponent, while aimed

(ultimately) at persuading an audience to cast votes in the candidate’s favor (1997: 269).

d. They say/ I say

A writer’s exigence provides an urgency, purpose and occasion for the discourse,

as Graff and Birkenstein (2006) continually emphasize in their academic writing guide,

They Say/ I Say: Moves that Matter in Academic Writing. In fact, Graff and Birkenstein

base their entire tutorial of academic writing on the controlling idea that successful

writers “state [their] ideas as a response to others,” that a statement/response dynamic is

arguments without being provoked.” (3). In saying this, they implicitly pick up on the

importance of considering the exigence of the rhetorical situation, insisting that “what

you are saying may be clear to your audience, but why you are saying it won’t be

[because] it is what others are saying and thinking that motivates our writing and gives it

reason for being” (Graff and Birkenstein, 2006: 4). What Graff and Birkenstein (2006)

seem to be promoting, in essence, is a re-contextualization of written discourse as an

outflow of the larger rhetorical situation. They highlight the fact that written discourse

must not be produced as if it were merely a bundle of written form stripped of its context,

but rather that, “the best academic writing has one underlying feature: it is deeply

engaged in some way with other people’s views” and does not consist of “saying ‘true’ or

‘smart’ things in a vacuum, as if it were possible to argue effectively without being in

conversation with someone else” (3).

2. Audience: Who are you speaking-writing to?

After the exigence for writing is firmly set in place, student writers should

consider an audience to whom the exigence of the discourse is relevant. The audience of

a rhetorical situation is comprised of real or imagined persons “with whom

[speaker-writers] negotiate through discourse to achieve the rhetorical objectives” (Grant-Davie,

1997: 270). Grant-Davie takes audience to mean four different sets of people: 1) any real

people who happen incidentally to hear or read the discourse, 2) the real people that the

discourse was intended to be read by, 3) the audience that the speaker-writer has in mind,

and 4) the audience that the discourse itself suggests (Grant-Davie, 1997: 270). The roles

of speaker-writers and hearer/hearers, however, “Are dynamic and interdependent” so

are “negotiated with the [speaker-writer] through the discourse” which “may change

during the process of reading” (Grant-Davie, 1997: 271). Overall, the role(s) of

speaker-writers and hearer/readers may shift and morph as the discourse, the speaker, and the

audience exert mutual influence upon one another to create new roles and accept new

identities.

a. Imagining an audience

Bartholomae (1985) also discusses the importance of students writing “initially

with a reader in mind,” imagining a reader, anticipating possible responses (1985: 627).

For the student writer, the challenge is to imagine a rhetorical situation and to make

communicative moves within a context that (often) does not exist. The “difficulty of this

act of imagination and the burden of such conformity” to the aims of the writing

pedagogy is “so much at the heart of the problem” (1985: 627). In fictionalizing their

audience, writers “have to anticipate and acknowledge the readers’ assumptions and

biases,” and in doing so, hopefully to detect their own assumptions and biases

(Bartholomae 1985: 628).

Among the writer’s most important objectives is to imagine an audience that hears

his or her response to an exigence, and to try on a variety of voices/identities in response

to this rhetorical situation. Ong (1975) holds that, rather than responding to actual people

in writing, a skillful writer will “construct in his imagination, clearly or vaguely, an

audience cast in some sort of role, entertainment seekers, reflective sharers of research”

(1975: 60). Ong elaborates that:

Where does he find his "audience"? He has to make his readers up, fictionalize them” (Ong 1975: 59).

In case one wants to make the intuitive proposal that the writing instructor is a sufficient

audience, Ong asserts, “there is no conceivable setting in which [the student writer] could

imagine telling his teacher how he spent his summer vacation other than in writing this

paper, so that writing for the teacher does not solve his problems but only restates them”

(59). Students instead must fictionalize both their attending audiences and their

responding voices.

To aid in the fictionalization of audience, Ong (1975) points out that writing

students can draw from “what [a] book felt like, how the voice in it addressed its readers,

how the narrator hinted to his readers that they were related to him and he to them [and

can] pick up that voice and, with it, its audience” (1975: 59-60). His point is that

successful writers owe much of their coherence and vividness to the fictionalization of

their audiences that otherwise would be impossible to invoke without the model of

“earlier writers who were fictionalizing in their imagination audiences they learned to

know in still earlier writers, and so on back to the dawn of written narrative” (Ong 1975:

60). Implicit in this view is something that Berman (2008) has found in her research: that

previous literary education has a direct influence on students’ ability to produce

well-formed academic discourse (2008). The fact that previous literary education is a major

factor in whether students successfully participate in the rhetorical situation (in this case

conceiving of audiences) is connected with Bakhtin’s contention that characters in novels

readers internalize and re-deploy these voices for later use in discourse production.

Authorial voice, therefore, is an outgrowth of audience.

b. Connecting with an audience using meta‐discourse markers

Having an audience in mind is related to several communicative components

(functions) of successful writing. Cheng & Steffensen (1996) provide seven criteria for

successful writing, out of which the “text-centered standard of coherence, and the

user-centered standards of acceptability, situationality, and informativity” are “clearly related

to concepts of audience” (1996: 150-151). Audience is something that writing students

“rarely have a clear sense of”—and when students do involve a rhetorical audience, “it is

a real person who gives a perceptible response - a teacher who provides a grade, not

someone with whom to create a dialogue” (1996: 152).

The standard of coherence refers to “the knowledge that provides the conceptual

undergirding of a text” which “must be accessible to both the writer and the reader” and

calls to attention the fact that “no text is completely explicit” and that readers must “share

enough back-ground knowledge to be able to make successful inferences and fill gaps”

(Cheng & Steffensen 1996: 151). The standard of acceptability “capture[s] the fact that

[…] the reader must accept the text as cohesive, coherent, and directed toward” the

writer’s goals (1996: 151). “Situationality,” another user-centered standard for successful

writing, “refers to the match between a text and the context for which it is intended;” and

finally “informativity, […] captures the fact that “writers must be able to anticipate the

amount of information shared by their readers” (1996: 152).

According to Cheng & Steffensen (1996), teaching students the explicit use of

organize their writing more, and consider the epistemological value of their propositions

more realistically (functions). Before, touching upon these findings, I want to define

discourse markers.

There is little agreement in the literature about what to call the connective

words/phrases that are strewn throughout written discourse, which many English as a

Second Language and remedial writing publications call transition words. Fraser (1996,

2005) seems to provide a useful classification of what he calls pragmatic markers, of

which he posits four types (Fraser 2005). Although “discourse markers” appear as only

one of the four types of Fraser’s pragmatic markers, I have adapted two of Fraser’s types

of pragmatic markers for my own classification of connecting words relevant to academic

writing, labeling all of them “discourse markers”—even those which Fraser calls

“commentary pragmatic markers” (2005: 1), under the five headings below, which

integrates many of the transitions that Graff & Birkenstein (2006) posit as commonly

used in academic writing (2006: 232-234). The reason for only including two types of

Fraser’s pragmatic markers in my own classification of discourse markers is that the two

other excluded types seem to be used in conversation (or in informal writing, such as

tweets or emails), and not in academic composition, which is the focus of this study.

Discourse markers that are useful in academic composition, therefore, are considered in

this study (with subheadings and examples) to be:

1) Elaborative discourse markers: signaling an addition or refinement of a preceding statement.

more to the point, moreover, on that basis, on top of it all, or, otherwise, rather, similarly, that is (to say)

2) Contrastive discourse markers: signaling a denial, contrast, or unexpected development of a preceding statement

Examples: but, alternatively, although, contrary to expectations,

conversely, despite (this/that), even so, however, in spite of (this/that), in comparison (with this/that), in contrast (to this/that), instead (of this/that), nevertheless, nonetheless, (this/that point), on the other hand, on the contrary, regardless (of this/that), still, though, whereas, yet

3) Inferential discourse markers: signaling a conclusion from a preceding statement.

Examples:so, after all, as a conclusion, as a consequence (of this/that), as a result (of this/that), because (of this/that), consequently, for this/that reason, hence, it follows that, accordingly, in this/that/any case, then, therefore, thus

4) Temporal discourse markers: signaling a shift in time or progression related to the discourse.

Examples:then, after, as soon as, before, eventually, finally, first, in the meantime, meanwhile, originally, second, subsequently

5) Meta-discourse markers: signaling a writer’s commentary to an audience about his/her discourse.

a. Assessment markers: signal a writer’s judgment/evaluation of the wider context (state of affairs) of the statement.

Examples: fortunately, sadly, strikingly, surprisingly, amazingly, astonishingly, hopefully, ideally, importantly, incredibly,

inevitably, ironically, justifiably, oddly, predictably, prudently, refreshingly, regrettably, (un)fortunately, (un)reasonably, (un)remarkably

b. Manner-of-speaking markers: signaling the way a writer conveys the statement.

seriously, simply, strictly, truthfully, to speak candidly, roughly speaking, to be honest, and in all seriousness, worded plainly, stated quite simply, off the record, quite frankly, in the strictest confidence

c. Evidential markers: signaling a writer’s level of confidence of the truth of the statement.

Examples: conceivably, certainly, indeed, assuredly, decidedly, definitely, doubtless, evidently, incontestably, incontrovertibly, indisputably, indubitably, (most/ quite/ very) likely, obviously, patently, perhaps, possibly, presumably, seemingly, supposedly, surely, (un)arguably, undeniably, undoubtedly

d. Hearsay markers: signaling a writer’s comment about the source of information of the statement.

Examples: reportedly, allegedly, I have heard, it appears, it has been claimed, it is claimed, it is reported, it is rumored, it is said, one hears, purportedly, they allege, they say

e. Topic change markers: signaling writer’s digression or departure from a current topic.

Examples: back to my original point, before I forget, by the way, incidentally, just to update you, on a different note, parenthetically, put another way, returning to my point, speaking of X, that

reminds me

One may notice that the above discourse markers are from four syntactic categories with

significant overlap in (discourse) function: 1) coordinate conjunctions (and, but, for, yet,

so), 2) subordinate conjunctions (while, since, although), 3) preposition phrases (above

all, rather than, in fact), and 4) adverb phrases (anyway, furthermore, still, however)

(Fraser, 2005: 6).

In an empirical study, Cheng & Steffensen (1996) showed how freshman

markers, meta-discourse being a device that “comments on the text itself or which directs

comments to the reader” (150). Cheng & Steffensen reported that students “experienced a

breakthrough in their consideration of the reader and an awareness of the rhetorical

functions of composition” when the students learned about the concept of meta-discourse

and meta-discourse features in terms of their rhetorical functions in an environmental

setting” (179). Specifically, students trained to use meta-discourse markers wrote with

more explicit structure and tone, an improved topical progression, an improved revising

processes, and more attention paid to a realistic epistemology (Cheng & Steffensen 1996:

171-176).

As regards improvement of structure and tone, Cheng & Steffensen pointed out

that meta-discourse makes “structure and tone explicit, by capturing them on paper”

enabling writers to “consider what they are saying more easily and make appropriate

changes and improvements” and leading them to revise with increased “attention [paid]

to the reader's perspective” (170).

In paying more attention to meta-discourse, students became more aware of the

epistemological value of their statements, realizing that “what they wrote was being

understood by their readers as their view of reality, and they became more ethical writers,

paying more attention to the truth value of their propositional content and hedging it

when necessary” (176).

3. Speaker-writer: What are your roles, identities, voices, and attitudes?

Speaker-writers are involved in the rhetorical situation as those, real or imagined,

Though Bitzer left the speaker (rhetor) out in his definition of the rhetorical situation, the

speaker-writer is just as much a constituent of the rhetorical situation as the audience,

Grant-Davies argues. The role(s) of the speaker-writer “are partly predetermined but

usually open to definition or redefinition” so that speaker-writers “need to consider who

they are in a particular situation and be aware that their identity may vary from situation

to situation” (Grant-Davie, 1997: 269). A Speaker-writer may be the originator of the

content of the discourse, or just a designee chosen to deliver it, or neither, yet held

accountable for the validity of the content (269). Authorial identity may shift, even, from

whom the speaker-writer considers himself to be, to whom the hearer/readers infer the

author’s identity or ethos to be. So, determining whom the speaker-writer is may not be

simple, as exigence and audience exert influence on the roles, the identities, and the

audience’s perception of the speaker-writer’s ethos. Interestingly, “new rhetorical

situations change us and can lead us to add new roles to our repertoire,” which calls for

“receptivity—the ability to adapt to new situations and not rigidly play the same role in

every one” (1997: 270).

a. Trying on different voices in writing

The concept of voice in writing is widely used, discussed, and debated. Yet,

according to Peter Elbow, there is no “critical consensus about voice” and the concept

“leads us into theoretical brambles” (2000: 227). Elbow (2000) discusses the different

ways in which voice has been characterized by different literary and composition

theorists, for which space in this paper is not committed, highlighting the potential

difficulty the concept could present for its analysis. Nevertheless, Elbow holds that “there

qualities in texts” (2000: 205). To put it briefly, Elbow thinks of voice in terms of 1)

audible voice, concerned with hearing the text; 2) dramatic voice, seeing every text as

having an implied character behind the words; 3) authoritative voice, aimed at giving a

more authoritative stance to overly deferent student writing; and 4) resonant voice, the

idea of the trustworthy, genuine writer sounding present, behind the words, evoking ethos

(2000: 226-227). A concise list follows of heuristically motivated questions that writing

teachers may use to help students think about each notion of voice (adapted from Elbow,

2000: 184-221, 226):

1) Audible voice

Are you able to hear this section? How much of it can you hear?

If you are stuck, can you read the section out loud and hear the problem? Look away from the paper and speak the idea out loud. How would you say it?

2) Dramatic voice

What kind of voice(s) do you imagine are speaking in this essay? - a timid voice, an angry voice, an arrogant voice, a bureaucratic voice, a professorial voice, multiple voices

What sort of speaker or character are you speaking as here? 3) Authoritative voice

Could you rephrase this part to sound more assertive?

Speak your mind more in this section. Are you afraid of offending someone?

How would you say this if you were (some other speaker) the president? 4) Resonant voice

How much of yourself did you get behind these words? Where is the real you in this section? Does it fit you? Could you rephrase this (part) so sound more like yourself? Could you be more sincere in this section?

Though each of these views of ‘voice’ is useful, I will focus on Elbow’s resonant voice to

frame my understanding of voice presented here, a concept of voice that depends upon

the analogy of one getting more of oneself behind his or her words; more than being

“points to the relationship between discourse and the unconscious” and “comes from

getting more of ourselves behind the words,” getting “more of our unconscious into our

discourse” (2000: 206, 207). Voices are tightly bound up with selves and identities,

which tend to “evolve, change, take on new voices, and assimilate them (2000: 208). In a

typically expressionistic way, Elbow holds that writing provides a crucial setting for

“trying out parts of the self or unconscious that have been hidden or neglected or

undeveloped—to experiment and try out ‘new subject positions’” (2000: 208).

Student writers need to explore and appropriate different voices that approximate

the identities that fit within the rhetorical situation. The process, of approximating and

re-approximating one’s own multiple, shifting, and fluid voices in writing is shaped by the

also-dynamic process of audience fictionalization. It is this intentional, meta-awareness

of one’s voice and audience that characterizes mature and skillful writers—the ability to

deploy different voices to meet different communicative ends.

Bartholomae (1985) reflected that whenever a “student sits down to write, he has

to invent the university for the occasion” by trying on different voices and interpretive

frameworks. “The student has to appropriate a specialized discourse,” Bartholomae says,

“and he has to do this as though he were easily and comfortably one with his audience”

(624).

2.6 Berman and the development of discourse

From the perspective of 1st Language Acquisition, Psycholinguistics, and

Form/Function linguistics, Berman and her international team investigated how children

Swedish, and American English in a large-scale project, known as the Spencer Project, or

officially as “Developing literacy in different contexts and different languages,” which

began in 19971.

The project involved the elicitation of written/spoken personal experience

narratives and expository texts from 80 individuals from the seven countries represented

by her team, evenly divided into four groups of 20 individuals each: Grade School (4th

graders, 9-10 years old), Junior High School (7th graders, 12-13 years old), High School

(11th graders, 16-17 years old), and Adults (university graduate students in their 20’s and

30’s). As Berman and her team thoroughly analyzed the 320-text corpus for patterns of

development across the independent variables of age-level, genre/modality, and language,

dozens of studies were published on the different findings that emerged from the analysis.

Berman and her colleagues wanted to describe “the linguistic, cognitive, and

communicative resources that [speaker-writers] deploy in adapting their texts to different

circumstances”—across modality and genre—“and to detect shared or different trends

depending on the particular target language” (Berman & Katzenberger 2004: 62). These

aims are summarized under the heading of measuring speaker-writer’s development of

1

Berman and her colleagues had previously studied the different developmental and linguistic aspects of children’s narrative discourse, inspired by the work of Dan Slobin at Berkeley who conducted work on children’s construction of oral narratives (1996). Berman & Slobin’s (1994) “Relating events in narrative: a crosslinguistic developmental study,” known as the “Frog picture story book” studies, analyzed and compared the oral fictive narratives of 3‐, 4‐, 5‐, 9‐year olds and Adults in English, German, Hebrew, Turkish, and Spanish. Evident in this work, Berman expressed a view of language acquisition as an integrated, protracted process

linguistic literacy. First outlined by Ravid & Tolchinsky (2002), the notion of “linguistic

literacy” (not merely the “literacy,” of reading/writing) is characterized by

speaker-writers possessing a varied repertoire of linguistic resources, the ability to access/deploy

these resources to meet different communicative ends in different contexts, and a

meta-linguistic awareness of the effect of using these different meta-linguistic forms in different

situations. Linguistic literacy develops toward its zenith of “rhetorical flexibility or

adaptability,” which means being “rhetorically expressive” enough to “hold the attention

of their addressee” with “interesting and varied linguistic output that is attuned to

different addressees and communicative contexts” (Ravid & Tolchinsky 2002: 418). Key

to the idea of rhetorical flexibility is the ability to intermingle features from different

genres (narrative and expository) and to adapt these features to be as “rhetorically more

powerful, convincing, and precise” as possible (2002: 435). Berman evokes and reiterates

the same idea of linguistic literacy as the developmental target in the first Spencer Project

article, referring to it as “the ability to readily and effectively access and deploy a wide

range of written materials in a given target language” (Berman & Verhoeven 2002: 14).

To measure speaker-writer’s developmental stages of the achievement of

linguistic literacy, or the production of well-formed discourse, Berman eventually

developed a complex analytical framework made up of the different aspects of discourse

production abilities (Berman 2008). Berman defined five aspects of discourse

construction that were quantifiable across language, age, and genre/modality and which

younger/older speaker-writers were found to deploy with gradual mastery at different

stages of development. The five “functionally motivated” discourse features comprise an

of referential content, to (3) clause-linking complex syntax, and (4) local linguistic

expression, and ending with (5) overall discourse stance; these aspects “apply

concurrently whenever a piece of discourse is produced” and are applied “in order to

meet the challenge of connecting cognitive representation and linguistic knowledge in

developing text construction” (Berman 2008: 737-740). Berman measured these five

discourse features across the variables of genre (narrative/expository), modality

(written/spoken), age, and language. These five facets of discourse production comprise

an innovative, complex, and empirically grounded model for characterizing written and

spoken discourse at the lowest and highest stages of development.

2.7 Discourse stance, referential content, and global text organization

Of these five facets, I will review three—discourse stance, categories of

referential content, and global text organization—which directly pertain to the aims of the

student writing guide, namely to help student-writers deploy forms of well-formed

expository, argumentative discourse. The two excluded facets, clause-combining

complex syntax and local linguistic expression were found to have low, even negative,

correlations with overall global text quality. Some speaker-writers who used advanced

vocabulary/syntax were found to construct “relatively flat or juvenile texts” while other

speaker-writers who used simple forms of local-linguistic expression produced (globally)

well-formed texts (Berman 2008: 757). Some of Berman’s subjects who scored high in

local linguistic expression scored low on global text quality and vice versa. This means

that lexico-syntactic complexity does not translate directly into well-organized global

discourse structure, clarity of thinking, or interesting content. The use of advanced forms

well-formed or even beyond-well-well-formed text. Therefore, I will only review and rely on the

facets of 1) global text organization, 2) categories of referential content, and 3) discourse

stance to inform and help construct the student writing guide.

1. Global text organization: Top-down (expository)/ bottom-up (narrative)

The first facet of discourse text production, global text organization, brings into

consideration the overall “structure and content of the text” and its “rhetorical effect” as

based on type of genre (2008 p.740-741). First discussed in Berman & Nir-Sagiv (2007),

global text organization depends on the notion of “mental representations of schema and

category […] anchored in the shared cognitive ability to interrelate parts and wholes”

(2007: 91). Speaker-writers demonstrate well-formed global text quality when they

produce narratives that organize isolated events (bottom-up) within an action structure

schema (top-down). Expository texts, on the other hand, are centered around one core

proposition (top-down) that is elaborated upon by specific instances and details

(bottom-up) (2008: 741). “Structural well-formedness” in the domain of global text quality is

achieved when speaker-writers integrate “top-down and bottom-up principles of

discourse organization” (Berman 2008: 741).

As different genres instantiate different cognitive representations and

organizational principles, a text is considered well-formed that meets the genre-canonic

global organizational structure. Younger speaker-writers typically rely only on one

organizational schema: either on top-down for expository texts, or on bottom-up for

narratives. Yet, a higher, more sophisticated level of text construction ability is