Ž .

Applied Animal Behaviour Science 68 2000 93–105

www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Effects of social facilitation for locating feeding

sites by cattle in an eight-arm radial maze

Derek W. Bailey

a,), Larry D. Howery

b, Darrin L. Boss

aa

Northern Agricultural Research Center, Montana State UniÕersity, Star Route 36, Box 43, HaÕre,

MT 59501, USA

b

School of Renewable Natural Resources, UniÕersity of Arizona, PO Box 210043, Tucson,

AZ 85721-0043, USA

Accepted 5 January 2000

Abstract

A study was conducted in an eight-arm radial maze to determine if cattle with various foraging experiences could facilitate location of feeding sites by other cattle. Heifers assigned as

‘‘fol-Ž .

lowers’’ ns24 were initially trained to expect straw at the end of each arm. Initial training of

Ž . Ž .

heifers assigned as ‘‘leaders’’ ns12 differed based on the three following treatments: 1

Ž . Ž .

no-experience, 2 barley in the same two arms, and 3 barley in two arms but locations changed daily. During training, leaders with barley in fixed locations foraged more efficiently by traveling

Ž .

to fewer P-0.05 arm ends to find barley than leaders in the variable treatment. After training, two followers were placed in the maze with a leader, and barley was available in two arms. Leaders facilitated the location of barley by followers. In 61% of the occasions that followers first found barley, leaders were at the feeding site. Eighty-one percent of followers later located barley without leaders in the maze. Followers with experienced leaders did not find barley consistently more often than heifers with inexperienced leaders. Cattle can apparently learn feeding site locations from other animals, but additional research is needed to evaluate the behavioral mechanisms that influence social facilitation during foraging.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Social facilitation; Spatial memory; Cattle; Foraging; Behavior

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q1-406-265-6115; fax:q1-406-265-8288.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] D.W. Bailey .

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

( ) D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105

94

1. Introduction

Free-ranging ungulates forage in landscapes where food quality and quantity vary in

Ž .

both space and time Senft et al., 1987 . The ability to track changes in forage resources should allow large herbivores to graze more efficiently because they would know where

Ž .

and what to graze Bailey et al., 1996 . Individual learning and social learning are the Ž

most probable mechanisms for livestock to obtain this critical information Provenza et

. Ž .

al., 1988 . Instinct genetics could be used to transfer forage resource information from one generation to another, but individual and social learning should be favored more on

Ž

rangelands due to spatial and temporal variation in forage quantity and quality Provenza .

and Balph, 1988 .

Several studies have shown that cattle individually can learn the location of food and Ž

then adjust their foraging patterns to take advantage of this knowledge Bailey et al., .

1989a; Laca, 1998; Howery et al., 2000 . Cattle also can associate locations with the

Ž .

quantity and quality of food found there Bailey et al., 1989b; Bailey and Sims, 1998 . Potentially, cattle could readily learn the location of feeding areas from other animals.

Ž .

For example, Howery et al. 1998 observed that domestic calves learn where to graze from their dam. In feral cattle, the integrity of social groups is high, and individuals

Ž .

regularly interact with herd members Lazo, 1994 . If an animal located an area with high food resources, this information could be transferred to other members of the social group.

Familiarity, social ranking and experience may affect the efficiency with which

Ž .

information is exchanged Mosley, 1999 , but few studies have specifically examined Ž .

the effect of social facilitation on cattle during foraging. Howery et al. 1999 showed that pen-mates transferred foraging information to other animals more efficiently than

Ž .

non-pen-mates. In another study, Sato 1982 suggested that movements of a cattle herd during grazing was directed by active movement of cattle with high-social ranking or the independent movement of low-ranking cattle.

The role of previous foraging experience on the ability of cattle to transfer foraging Ž . information has received little examination. The objectives of this study were: 1 to

Ž .

determine if cattle followers could learn the location of a new source of food directly

Ž . Ž

from a social model and 2 to determine if the foraging experiences i.e., fixed, .

variable, or no-experience of the social models would affect the rate of learning by followers.

2. Methods

2.1. Study apparatus

Ž .

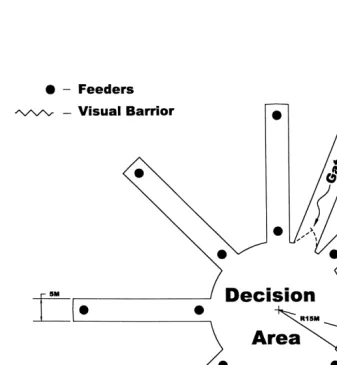

The study was conducted in an eight-arm radial maze Fig. 1 . The central decision

area was 30 m in diameter, and arms were 5=35 m. The maze was constructed from

electric fence in a level area that had been mowed to a 5-cm stubble height. Animal sorting pens were located approximately 100 m from the central decision area. Large hay stacks prevented animals in the holding and sorting pens from seeing the maze.

Ž . Ž

Opaque feed pans 0.5 m diameter and 0.2 m sides were placed at the entrance 5 m

. Ž .

( )

D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105 95

Fig. 1. Diagram of eight-arm radial maze containing eight feeders near arm entrances and eight feeders at arm ends.

Ž .

Eight-arm radial mazes have been used for several species rats, pigeons and cattle Ž

to study spatial memory Beatty and Shavalia, 1980; Roberts and Van Veldhuizen, 1985; .

Bailey et al., 1989a . This apparatus is useful for examining spatial choices of feeding sites because the distances to all feeding sites are similar, and the sequence of feeding

Ž . site selections is relatively independent of the path taken Fig. 1 .

2.2. Animals

( ) D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105

96

animals grazed in the same pastures or were fed in the same drylot for at least 6 months before the study. During the study, groups of heifers grazed in a common pasture from

Ž .

14:00 to 08:00 h interval between trials .

Within a group, three animals were randomly selected as leaders. The remaining six heifers were randomly assigned as three pairs of followers. Each pair of followers was randomly assigned to one of the leaders. For the purposes of this study, leaders refer to animals that have received different training and experience in the maze than followers. As a result of the initial training, leaders were expected to locate highly palatable feed at arm ends at different rates than followers when leaders and followers were in the maze during the same sessions.

2.3. Initial training — leaders

Ž

Treatments were based on three initial training regimes of the leaders i.e., experi-.

enced-fixed, experienced-variable, and no-experience; Table 1 . One of the three leaders within a group was not allowed to travel to the end of maze arms and consume barley

Ž .

during the 7 contiguous days of initial training no-experience treatment . Gates placed in each arm 10 m from the decision area restricted access of the no-experience treatment leaders to the end of the arms.

The ‘‘experienced-fixed’’ treatment was based on a leader that received 0.8 kg of ground barley at the end of the same two arms during each of the 7 days of initial training. Maze arms with barley were determined by first randomly selecting one of the eight arms and then randomly selecting one of the remaining five arms that were not adjacent to the arm selected first. The purpose of this restriction was to prevent heifers from selecting a specific section of the maze. After much training, cattle may adopt a

Ž .

strategy of choosing adjacent arms in radial maze studies Bailey and Sims, 1998 . The ‘‘experienced-variable’’ treatment was based on a leader that also received 0.8 kg of ground barley at the end of two maze arms, but the maze arms changed daily during the 7 days of initial training. The locations of the maze arms with barley were assigned randomly with the restrictions that arms were not adjacent and that the same arm was not used 2 days in a row.

All eight inside feeders, near arm entrances, contained 0.2 kg of whole oats during initial training of all leaders. The oats were placed at arm entrances so that animals would enter all maze arms, and failure to travel to arm ends would not be the result of animals being reluctant to enter a particular arm. For the experienced-fixed and experienced-variable leaders, 0.05 kg of straw was placed in the six feeders at the end of maze arms that did not contain barley. Heifers rarely consumed straw throughout the study.

Leaders were individually herded to the maze and released in the decision area for 20 min or until all feeders with grain had been visited. If a feeder with grain had not been

Ž .

visited after 20 min usually feeders at arm ends with barley , observers herded the heifer to the feeders containing grain, and the visit was recorded as an assisted choice.

2.4. Initial training — followers

( )

D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105 97

considered as an experimental unit. Initial training for all followers was identical. All feeders at the end of maze arms contained 0.05 kg of straw. Inside feeders contained 0.4

Ž .

kg of whole oats 0.2 kgrheifer . For the first 4 days of initial training, heifers were

herded to the end of two randomly chosen arms after 20 min in the maze. The purpose of this herding was to ensure that heifers had the opportunity to observe and expect straw at arm ends. At the end of initial training, followers usually entered all arms and consumed the oats in the inner feeders, but rarely traveled to arm ends.

2.5. Pretest — followers

Ž .

In previous maze studies, Bailey et al. 1989a showed that cattle used spatial

memory rather than olfactory cues to locate grain. The purpose of the pretest was to confirm that heifers were not using olfactory or some other cue to locate grain in this study. On day 7 after initial training, 0.8 kg of ground barley was placed at the end of two maze arms. The location of barley was randomly selected with the constraint that selected arms were not adjacent to one another. Heifers were allowed 20 min in the maze. Observers did not attempt to herd or assist heifers in any way.

2.6. Exposure to leaders and test sessions

Ž .

After initial training and the pretest Table 1 , a pair of followers were exposed in the

Ž .

maze with their associated leader for one 30-min session exposure session and then Ž evaluated without the leader for two 20-min sessions on the following 2 days test

.

sessions . This process was repeated a second time for each leader and pair of followers. During the exposure sessions, the leader and associated followers were herded into the maze together and released. During test sessions, only followers were evaluated in the maze, while leaders received the same protocol as during initial training. For both the

Ž .

exposure and test sessions, ground barley 0.8 kgrfeeder was placed at the end of two

arms in the identical locations as the follower pair received during the pretest, and whole

oats were placed in the inside feeders at a rate of 0.2 kgrheifer.

2.7. BehaÕiors obserÕed

Ž .

Prior to the study, oats and barley 0.5 kg were offered in feeders in a separate

25=25 m pen. Each heifer was observed individually for 10 min, and the number of

vocalizations, movement, the amount and type of grain consumed and a 1 to 5

Ž .

temperament rating 1scalm, 5swild and unmanageable were recorded.

During all phases of the study, the following information was observed for each individual animal: time in maze, sequence of arms entered, time that each animal

Ž

entered and exited each arm, distance traveled down each arm e.g., 1 4, 1 2, 3 4 and .

end , time spent at arm ends and whether an animal placed its muzzle in the feeders at arm ends.

2.8. Analyses

2.8.1. Leaders

The behaviors of leaders in the experienced-fixed and experienced-variable treat-ments were compared using paired t-tests to examine whether the distribution of two

Ž .

()

D.W.

Bailey

et

al.

r

Applied

Animal

Beha

Õ

iour

Science

68

2000

93

–

105

98

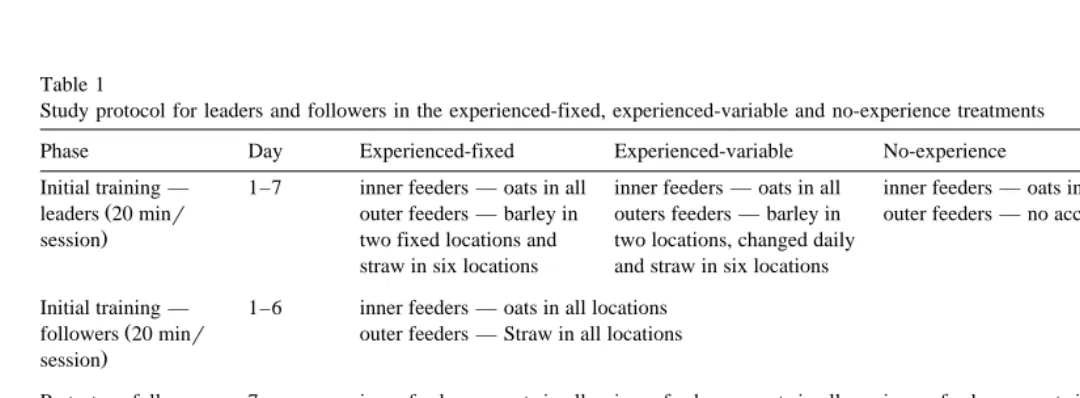

Table 1

Study protocol for leaders and followers in the experienced-fixed, experienced-variable and no-experience treatments

Phase Day Experienced-fixed Experienced-variable No-experience Purpose

Initial training — 1–7 inner feeders — oats in all inner feeders — oats in all inner feeders — oats in all train leaders to respond to

Ž

leaders 20 minr outer feeders — barley in outers feeders — barley in outer feeders — no access different spatial treatments

.

session two fixed locations and two locations, changed daily straw in six locations and straw in six locations

Initial training — 1–6 inner feeders — oats in all locations train followers to expect straw

Ž

followers 20 minr outer feeders — Straw in all locations at arm ends

.

session

Pretest — followers 7 inner feeders — oats in all inner feeders — oats in all inners feeders — oats in all confirms that followers were not

Ž20 minrsession. outer feeders — barley in outer feeders — barley in outer feeders — barley in using olfaction to locate grain two random locations and two random locations and two random locations and

straw in six locations straw in six locations straw in six locations

Exposure 1 — 8 inner feeders — oats in all inner feeders — oats in all inner feeders — oats in all facilitate information transfer leaders and followers outer feeders — barley in outer feeders — barley in outer feeders — barley in from leaders to followers

Žtogether 30 minŽ r same locations as during same locations as during same locations as during

.

session pretest and straw in six pretest and straw in six pretest and straw in

()

D.W.

Bailey

et

al.

r

Applied

Animal

Beha

Õ

iour

Science

68

2000

93

–

105

99

Test 1 — followers 9 and 10 inner feeders — oats in all inner feeders — oats in all inner feeders — oats in all test rate of information transfer

Ž20 minrsession. outer feeders — barley in outer feeders — barley in outer feeders — barley in from leaders to followers same locations as during same locations as during same locations as during

exposure 1 and straw exposure 1 and straw exposure 1 and straw in six locations in six locations in six locations

Post-exposure 9 and 10 same as initial — oats in same as initial — oats in same as initial — oats in continue training of leaders to

training — leaders inner feeders. inner feeders inner feeders respond to diffirent spatial

Ž20 minrsession. barley in two outer feeders barley in two outer feeders no access to outer feeders treatments

Žfixed location and six. Žlocations changed daily.

with straw and six with straw

Exposure 2 — 11 same as exposure 1 same as exposure 1 same as exposure 1 same as exposure 1

leaders and followers

Ž

together 30minr .

session

Test 2 — followers 13 and 14 same as test 1 same as test 1 same as test 1 same as test 1

( ) D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105

100

affected foraging strategies. Behaviors evaluated were assists, total arm entrances before 1 and 2 barley feeders were discovered, and the total number of occasions that heifers traveled to arm ends before finding one or two feeders with barley. Heifers often entered arms and consumed oats without traveling to arm ends. Thus, arm entrances were indicators of the search for oats, and travel to arm ends indicated a search for barley. Ž .

Average values from the last 2 days of initial training were evaluated. Groups ns4

were used for pairing.

2.8.2. Followers

For all three treatments, followers were treated identically during initial training and the pretest. All followers received barley in the same fixed locations during the pretest, exposure, and test sessions. For followers, the only difference among treatments occurred during the two exposure sessions when ‘‘leader’’ heifers that had previously

Ž .

received different initial training i.e., fixed, variable, no-experience were allowed to forage with the followers.

The effect of leader initial training on the behavior of heifers assigned as followers was analyzed as a randomized complete block design. Initial training regimes of leaders

Ž . Ž . Ž .

were the treatments ns3 and heifer groups nine animals were blocks ns4 .

Dependent variables analyzed were the total visits to barley feeders by followers during

Ž . Ž .

the two exposure with leader and four test sessions without leader and the total Ž number of visits to barley feeders by followers during the four test sessions without

. Ž .

leaders . Observational data obtained from leaders including exposure sessions were never included in analyses of follower data. Single degree of freedom orthogonal contrasts were used to determine if followers with experienced leaders differed from followers with inexperienced leaders. We hypothesized that followers with experienced leaders would find barley feeders sooner and visit more barley feeders than those exposed with inexperienced leaders.

A separate analysis using pooled data from all followers was used to evaluate if leaders facilitated the discovery of barley feeding sites by followers. A non-parametric binomial test was used to determine if followers visited arm ends with barley more often than expected by chance. The percentage of time spent by leaders at feeders during exposure sessions was calculated from observations to evaluate the probability that leaders were present at the time followers first found barley. Because followers had been

Ž .

trained to expect straw at arm ends and previous research Bailey and Sims, 1998 showed that cattle strongly avoided maze arms that contained straw, the timing in which

Ž .

followers visited barley feeders before, during or after a leader visit was used to evaluate if leaders facilitated the discovery of barley feeders by followers. Leaders from all three treatments could provide new information since they were not trained to avoid arm ends.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Leader behaÕior during initial training

( )

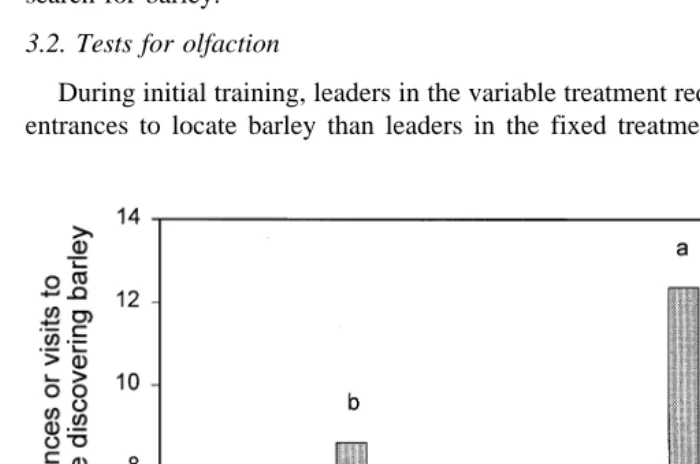

D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105 101 Ž .

experienced-variable treatment required more assists than the no-experience Ps0.03

Ž .

and experienced-fixed Ps0.08 treatments. Assistance for the experienced-fixed and

Ž .

no-experience treatments were similar Ps0.2 . Ninety percent of the assists occurred

during the first 4 days of initial training. After 5 days of training, leaders with barley in Ž .

fixed locations entered fewer Ps0.01 arms before finding barley than leaders with

Ž .

barley in variable locations Fig. 2 . Leaders with barley in variable locations traveled to the end of maze arms more frequently than the fixed location leaders before finding the

Ž . Ž .

first Ps0.08 and second Ps0.02 barley feeder.

Leaders in the two treatments appeared to use different search strategies. Leaders with barley in fixed locations usually entered an arm containing barley within their first two or three choices. As they entered an arm they usually consumed the oats in the inner feeder and then traveled to the end for barley. Leaders with barley in variable locations often consumed the oats in most of the inner feeders before traveling to arm ends to search for barley.

3.2. Tests for olfaction

Ž .

During initial training, leaders in the variable treatment required more P-0.05 arm

Ž .

entrances to locate barley than leaders in the fixed treatment Fig. 2 , which suggests

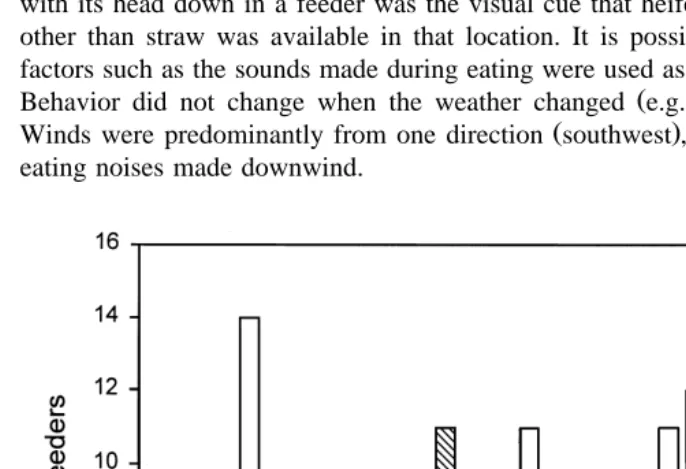

Fig. 2. Mean number of arm entrances and visits to arm ends by experienced-fixed and experienced-variable leaders before the first and second feeders with barley were discovered during the last 2 days of initial training

Ždays 6 and 7 . Entry-1 and Entry-2 refer to the total number of arm entrances before one or two barley feeders.

were found, respectively. End-1 and End-2 refer to the total number of arm ends visited before the first and second barley feeders were found, respectively. Means within each entry or end comparison that do not share a

Ž .

( ) D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105

102

that cattle did not rely on olfaction to locate food in the maze. If heifers had been using olfactory cues to locate barley, arm entrances required to find barley should have been similar for the fixed and variable location leaders. Moreover, followers did not find barley during the pretest, before exposure with leaders. Similar to other research with

Ž .

cattle Bailey et al., 1989a,b; Laca, 1998 , heifers in this study apparently did not use olfactory cues to locate grain.

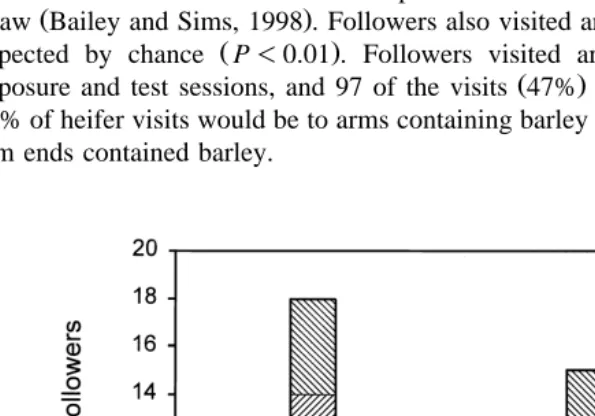

3.3. General social facilitation effects

During the study, followers had the opportunity to visit and consume barley in 24 Ž

total locations two locations per pair of followers, three pairs per group, and four .

groups . Followers visited and consumed grain at least once in 18 of the 24 locations

Ž75% . Because followers had been trained to expect straw at arm ends during initial.

training, finding 75% of the barley locations suggests that social facilitation may have occurred because heifers would be expected to avoid maze arms that were paired with

Ž .

straw Bailey and Sims, 1998 . Followers also visited arms with barley more often than Ž .

expected by chance P-0.01 . Followers visited arm ends 205 times during the

Ž .

exposure and test sessions, and 97 of the visits 47% were to arms with barley. Only 25% of heifer visits would be to arms containing barley by chance since two of the eight arm ends contained barley.

Fig. 3. Total number of barley feeders located during exposure and test sessions by followers exposed with leaders in the experienced-fixed, experienced-variable and no-experience treatments. The first bar represents the total number of barley feeders found out of a possible 24. The remaining three bars show the number of

Ž .

barley feeders visited simultaneously by both leader and a follower with leader , number of barley feeders

Ž . Ž .

( )

D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105 103 Ž .

A leader was present during 11 of the 18 occasions when a follower s first visited a Ž .

feeder with barley Fig. 3 . This is significant because leaders were only present during

Ž .

two of the seven trials that followers were exposed to barley 29% of the total time , and leaders spent less than 40% of their time in the maze within arms with barley. The probability of a leader being present at the arm end when a follower discovered a feeder with barley is less than 0.05 if one considers that leaders spent about 40% of their time in arms with barley at the end feeders. During test sessions, followers returned to feeders

Ž .

with barley a second time on 8 of the 11 occasions 83% after they first visited it when a leader was present.

Followers usually did not find a feeder with barley if the leader did not visit it first. Four of the six feeders with barley, not found by followers during the study, were in the no-experience treatment where leaders did not find the barley. We noted that followers appeared to redirect their route to the barley feeder when they noticed the leader foraging at a feeder. Our data support the hypothesis that cattle with knowledge of food locations can pass that information to its peers. It is our supposition that a conspecific with its head down in a feeder was the visual cue that heifers used to predict that food other than straw was available in that location. It is possible, but unlikely, that other factors such as the sounds made during eating were used as cues to locate feeding sites.

Ž .

Behavior did not change when the weather changed e.g., windy versus calm days .

Ž .

Winds were predominantly from one direction southwest , which would have muffled eating noises made downwind.

Fig. 4. Total number of visits to barley feeders by followers during exposure and test sessions in the

Ž

experienced-fixed, experienced-variable and no-experience treatments for the four groups experimental

.

( ) D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105

104

3.4. Effect of leader training on social learning

Initial training of leaders did not affect the total visits to barley feeders by followers

ŽPs0.4 or the visits to barley during the test sessions P. Ž s0.6 . The mean number.

Ž .

visits to barley was similar P)0.8 among groups of heifers. However, the behavior of

individual followers in the no-experience treatment of group 2 differed from those in the

Ž . Ž .

other three groups Fig. 4 . One of the followers heifer 5094 found both barley feeders Ž .

on the second day of the first test session day 10 . At that point, heifer 5094 acted as a leader and the no-experience leader and the other follower accompanied her to the barley feeders on the second exposure the next day. Based on initial observations, heifer 5094 was the least docile of the heifers used in the study. This heifer often traveled down maze arms several times during a session and appeared to be attempting to get out of the maze. After finding the barley, she consistently returned to those maze arms.

4. Conclusions

Leaders that could predict the location of more distant but greater food rewards

Žexperienced-fixed often chose those sites i.e., barley at the beginning of a foraging. Ž .

session. Leaders that could not predict the exact location of distant food rewards

Žexperienced-variable usually consumed most of the nearby, but less abundant, food.

Ži.e., oats before searching for the distant larger rewards..

Followers used leader animals as social models to locate barley feeders at the end of maze arms. Although the followers had been trained to expect straw at the end of maze arms, most followers responded to and learned from the lead animals that found and consumed barley. Animals with previous experience can function as social models and provide visual cues to other animals about the location of food.

One animal without prior experience found the barley feeders and led the no-experi-ence leader and a follower to the barley. Therefore, inexperino-experi-enced animals may also facilitate foraging of other individuals if they happen to locate a new food source. This

Ž

behavior would be adaptive under free-ranging conditions when natural e.g., fire,

. Ž .

drought or man-made e.g., road construction, food plots alterations affect forage availability across landscapes.

References

Bailey, D.W., Gross, J.E., Laca, E.A., Rittenhouse, L.R., Coughenour, M.B., Swift, D.M., Sims, P.L., 1996. Mechanisms that result in large herbivore grazing distribution patterns. J. Range Manage. 49, 386–400. Bailey, D.W., Rittenhouse, L.R., Hart, R.H., Richards, R.W., 1989a. Characteristics of spatial memory in

cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 23, 331–340.

Bailey, D.W., Rittenhouse, L.R., Hart, R.H., Swift, D.M., Richards, R.W., 1989b. Association of relative food availabilities and locations by cattle. J. Range Manage. 42, 480–482.

Bailey, D.W., Sims, P.L., 1998. Association of food quality and locations by cattle. J. Range Manage. 51, 2–8. Beatty, W.M., Shavalia, D.A., 1980. Spatial memory in rats: time course of working memory and effects of

( )

D.W. Bailey et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 68 2000 93–105 105

Howery, L.D., Bailey, D.W., Ruyle, G.B., 1999. Can food quality and location information be socially transmitted by cattle? Abstr. — Ann. Meeting. Soc. Range Manage. 52, 34–35.

Howery, L.D., Bailey, D.W., Ruyle, G.B., Renken, W.J., 2000. Cattle use visual cues to track food locations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 67, 1–14.

Howery, L.D., Provenza, F.D., Banner, R.E., 1998. Social and environmental factors influence cattle distribution. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 55, 231–244.

Laca, E.A., 1998. Spatial memory and food searching mechanisms of cattle. J. Range Manage. 51, 370–378. Lazo, A., 1994. Social segregation and the maintenance of social stability in a feral cattle population. Anim.

Behav. 48, 1133–1141.

Mosley, J.C., 1999. Influence of social dominance on habitat selection by free-ranging ungulates. In:

Ž .

Launchbaugh, K.L., Mosley, J.C., Sanders, K.D. Eds. , Grazing Behavior of Livestock and Wildlife. Idaho For. Range Exp. Stn. Bull. 70 University of Idaho, Moscow, ID.

Provenza, F.D., Balph, D.F., 1988. Development of dietary choice in livestock on rangelands and its implications for management. J. Anim. Sci. 66, 2356–2368.

Provenza, F.D, Balph, D.F., Olsen, J.D., Dwyer, D.D., Ralphs, M.H., Pfister, J.A., 1988. Toward understand-ing the behavioral responses of livestock to poisonous plants. In: James, L.F., Ralphs, M.H., Nielsen, D.B.

ŽEds. , The Ecology and Economic Impact of Poisonous Plants on Livestock Production. Westview Press,.

Boulder, CO, pp. 407–424.

Roberts, W.A., Van Velduizen, N., 1985. Spatial memory in pigeons on the radial maze. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Processes 11, 241–260.

Sato, S., 1982. Leadership during actual grazing in a small herd of cattle. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 8, 53–65. Senft, R.L., Coughenour, M.B., Bailey, D.W., Rittenhouse, L.R., Sala, O.E., Swift, D.M., 1987. Large