Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:16

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Teaching Higher Order Thinking in the

Introductory MIS Course: A Model-Directed

Approach

Shouhong Wang & Hai Wang

To cite this article: Shouhong Wang & Hai Wang (2011) Teaching Higher Order Thinking in the Introductory MIS Course: A Model-Directed Approach, Journal of Education for Business, 86:4, 208-213, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.505254

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.505254

Published online: 21 Apr 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 267

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.505254

Teaching Higher Order Thinking in the Introductory

MIS Course: A Model-Directed Approach

Shouhong Wang

University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Dartmouth, Massachusetts, USA

Hai Wang

Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

One vision of education evolution is to change the modes of thinking of students. Critical thinking, design thinking, and system thinking are higher order thinking paradigms that are specifically pertinent to business education. A model-directed approach to teaching and learn-ing higher order thinklearn-ing is proposed. An example of application of the proposed approach to teaching the introduction management information systems course is presented.

Keywords: higher order thinking, introductory MIS course, model-directed approach, peda-gogy design

Higher order thinking has been an important learning out-come in education. For instance, the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB; 2003), the global accreditation agency for business education, adopted a new set of standards for business schools accreditation. The stan-dards of Management of Curriculum suggest that skills of reflective thinking, or higher order thinking, should be an im-portant outcome of business education (AACSB). The chal-lenge of higher order thinking raises a significant research question: how to teach higher order thinking in the busi-ness curriculum (Braun, 2004; Crittenden & Woodside, 2007; McEwen, 1994). In the present article we discuss higher or-der thinking paradigms, propose a model-directed approach to teaching higher order thinking, and report an example of application of this approach to teaching the introductory MIS course.

PARADIGMS OF HIGHER ORDER THINKING

Higher order thinking is more than simple memorization and comprehension, and involves a variety of cognitive processes, such as making judgment, generating ideas, exploring

conse-Correspondence should be addressed to Shouhong Wang, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Department of Decision and Information Sci-ences, 285 Old Westport Road, Dartmouth, MA 02747, USA. E-mail: swang@umassd.edu

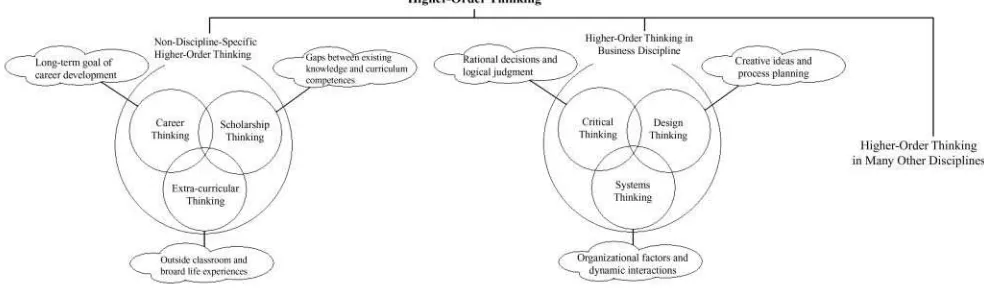

quences, reviewing options, monitoring progress, and so on (Perkins, Jay, & Tishman, 1993). Higher order thinking has been studies for a long time (Fisher, 2001). There are have been many terms for phrasing higher order thinking in the lit-erature, such as reflective thinking, integrative thinking, and deep thinking. The taxonomy of higher order thinking has not been made clear in the literature; however, higher order thinking is discussed in two streams: non-discipline-specific and discipline-specific. Typical paradigms of non-discipline-specific higher order thinking are career thinking, scholarship thinking, and extracurricular thinking (Zubizarreta, 2004). Research (Ericsson & Smith, 1991) into discipline-specific higher order thinking argues that discipline knowledge can guide sophisticated higher order thinking for the discipline. In this study, we place the focal point on the discipline of business.

In the business education literature, critical thinking, de-sign thinking, and systems thinking are three general higher order thinking paradigms that have been discussed widely. They are all related to problem solving in the business disci-pline.

Critical Thinking

Theories and practices of critical thinking have been widely disseminated (e.g., Jenkins, 1998; Page & Mukherjee, 2007; Peach, Mukherjee, & Hornvak, 2007). In this study, we defined critical thinking as the ability to explore a prob-lem, integrate all the available information about it, derive a

TEACHING HIGHER ORDER THINKING 209

decision, and justify the decision (Kida, 2006). Critical think-ing is required for solvthink-ing unstructured problems or makthink-ing unstructured decisions, and is a rational process of evalu-ating a claim or belief. Simon (1976) laid the foundation for the theory of behavioral and cognitive processes en-gaged in decision making. Critical thinking involves gather-ing appropriate information, evaluatgather-ing alternative answers pertinent to the information, and choosing the answer that is best supported by the information. In using information to evaluate alternatives based on decision-making model(s), critical thinkers recognize assumptions, biases, and uncer-tainty. Critical thinkers keep observing the outcomes of the execution of the decision and develop knowledge through internalization.

Design Thinking

Design thinking is a rigorous body of knowledge about the design process as a means of approaching managerial prob-lems (Simon, 1996). Under the design-thinking paradigm, people would be encouraged to think broadly about prob-lems and issues, develop an educated idea, and plan a pro-cess to implement the idea. Design thinking is different from critical thinking in that design thinking is process-oriented whereas critical thinking is judgment-oriented. For instance, optimization approaches emphasize more on critical think-ing, but less on design thinking. Design thinking results from the nature of design work: a project-based workflow around problems (Dunne & Martin, 2006). The major task in ex-ercising design thinking is the development of processes to achieve the identified goal.

Systems Thinking

Systems thinking paradigm originated from systems theories that the whole is more than the sum of the parts and every part has an effect on the whole system’s behavior (Gharajedaghi, 1999). The essence of systems thinking is focused attention to dynamic interaction factors of organizational networks (Checkland, 1981; Senge, 1996). The systems thinking

ap-proach allows managers to visualize a managerial problem as a system of components (structures, entities, events, and fac-tors), and understand how interdependent components (e.g., social, personal, and technological) impacted each other. Ap-plying systems thinking to management is necessary as man-agement involves multiple interdependent components.

A comparison of the thinking paradigms is illustrated in Figure 1. Clearly, the cut lines between the higher order thinking paradigms can never be sharp. Also, it is not the objective of this study to identify other less widely discussed types of higher order thinking in the business education lit-erature. The focal point of this discussion is to gain more understanding about the different paradigms of higher order thinking and to investigate how we can teach higher order thinking in these paradigms.

EMBEDDING HIGHER ORDER THINKING IN THE INTRODUCTORY MIS COURSE

Although teaching higher order thinking is still open to re-search, this study suggests using models and thinking queries for fostering higher order thinking. We explain this approach through an example of teaching higher order thinking in the introductory MIS course.

Course Overview

The introductory MIS course is a business core course for all business majors at most business schools (Ives et al., 2002). Business curricula use it to bridge the IT-user gap (Stephens & O’Hara, 2001). Because of the constraints of the AACSB curriculum structure, this course is usually the only required MIS course for business majors in most business schools. It is a common phenomenon for this course to have multiple sections taught by a mixed group of instructors. The course syllabi and assessment instruments used by individual instructors are often highly diversified. To improve the overall teaching–learning quality and coordinate multiple sections

FIGURE 1 Higher order thinking paradigms.

of this course, methodical assessment is needed to engage students in active learning.

In this course, students learn the concept of system, com-ponents of MIS, roles of MIS that influence organizational competitiveness, IT infrastructures in modern organizations, the unique economics of information and MIS, MIS-enabled business processes and decision support techniques, MIS development and acquisition, the nature of MIS manage-ment, and social and global subjects, such as ethics, cyber crime, security, and cultural issues relative to MIS. Given the breadth of the topics and how the concept of MIS has diffused throughout the business curriculum, it is natural to have a va-riety of approaches to teaching of this course. Nevertheless, lectures, technical hands-on experiences, case analysis, essay writing, and team projects are the major teaching methodolo-gies used by the instructors of this course.

Tools and Instruments for Teaching Higher Order Thinking: Models and Queries

Model is an important tool, if not the only one, that compels higher order thinking in business education (Dunne & Martin, 2006). While the ultimate models in great managers’ mind might not be available, models taught in business courses provide guidelines for higher order thinking. For instance, the decision-making model (Simon, 1976) can help students develop critical-thinking dispositions. Students should apply the model to any managerial decisions in all business subjects across the business education curriculum, and think about the decision making as well as the important roles of data and information in decision making.

Research has found that higher order thinking related questions are effective instruments for teaching and learning higher order thinking (Snapp & Glover, 1990). The teacher can use a model to raise questions, or thinking queries, for students to foster higher order thinking. For instance, the decision-making model can have thinking queries, such as the following: “How is the decision making model related to the case you analyzed?” and “Why did the decision in the case you analyzed succeed or fail from the perspec-tive of the decision making model?” Students’ work arti-facts can be linked to these queries for learning higher order thinking.

There are two types of thinking queries: typical and student-work-specific. Typical thinking queries are generic ones that are pertinent to the model and can generally be applied to all students’ work. Typical forms of questions for higher order thinking include purpose of study, content of work, format of analysis, process of learning, and evalua-tion of learning outcomes (Claywell, 2001). A student-work-specific thinking query is constructed to address a particular student’s work. For instance, when the teacher does not find a student’s reflection report adequate, the teacher might want to raise the student’s thinking to the next level by articulat-ing additional thinkarticulat-ing queries specifically for this student.

Clearly, student-work-specific thinking queries are more dy-namic and require much efforts of the teacher in facilitating higher order thinking.

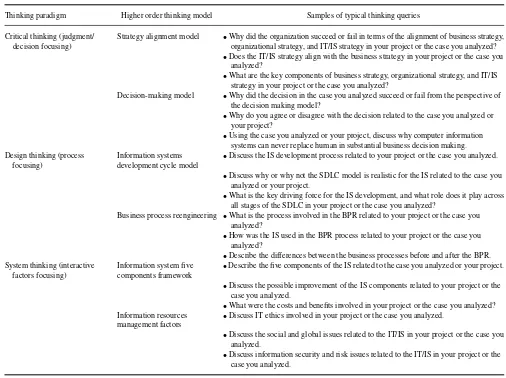

In this course, we have identified six models for the three higher order thinking paradigms, as summarized in Table 1. For critical thinking, there are the strategy alignment and decision-making models. For design thinking, there are the information systems development cycle and business pro-cess reengineering models. For systems thinking, there are the information system five components framework and in-formation resources management factors. For each model, we developed a set of queries for fostering higher order think-ing. Examples of typical thinking queries are exhibited in Table 1.

Exercise of Higher Order Thinking

The six models can be observed in almost every textbook for the introduction information systems course (e.g., Rainer & Turban, 2009). However, traditionally, instructors focus more on comprehension of the models, but less on higher order thinking through these models. Teaching higher order thinking through the use of these models is different from teaching these models per se in the following two aspects.

1. The emphasis of the present teaching approach is the three paradigms of higher order thinking. Students are given an overview of critical thinking, design thinking, and system thinking in the early stage of the course. The objective of learning these models is conducting higher order thinking through the use of these models as instruments.

2. The tactic of the present teaching approach is to inte-grate knowledge learned from the entire course or even other courses relevant to these models in the context for reflective higher order thinking. For instance, students are encouraged to apply business process reengineer-ing model to develop design thinkreengineer-ing on IT supported supply chain management.

The exercise ground for students to learn higher order thinking in this course is reflective writing. The exercise of higher order thinking helps students to articulate well focused, well organized, and well supported arguments and viewpoints through elaborate writing. We used three types of reflective writing: integrated case analysis, reflection essay, and self-evaluation of higher order thinking.

Integrated case analysis requests students to analyze a small case provided in the textbook. Most textbook cases provide case study questions, which associate the case with the course material, to guide the discussion. For teaching and learning higher order thinking, we take one step further by posing additional thinking queries for students to develop higher order thinking in the pertinent thinking paradigms.

TEACHING HIGHER ORDER THINKING 211

TABLE 1

Examples of Thinking Models and Queries for Teaching Higher Order Thinking

Thinking paradigm Higher order thinking model Samples of typical thinking queries

Critical thinking (judgment/ decision focusing)

Strategy alignment model •Why did the organization succeed or fail in terms of the alignment of business strategy, organizational strategy, and IT/IS strategy in your project or the case you analyzed?

•Does the IT/IS strategy align with the business strategy in your project or the case you analyzed?

•What are the key components of business strategy, organizational strategy, and IT/IS strategy in your project or the case you analyzed?

Decision-making model •Why did the decision in the case you analyzed succeed or fail from the perspective of the decision making model?

•Why do you agree or disagree with the decision related to the case you analyzed or your project?

•Using the case you analyzed or your project, discuss why computer information systems can never replace human in substantial business decision making. Design thinking (process

focusing)

Information systems development cycle model

•Discuss the IS development process related to your project or the case you analyzed.

•Discuss why or why not the SDLC model is realistic for the IS related to the case you analyzed or your project.

•What is the key driving force for the IS development, and what role does it play across all stages of the SDLC in your project or the case you analyzed?

Business process reengineering •What is the process involved in the BPR related to your project or the case you analyzed?

•How was the IS used in the BPR process related to your project or the case you analyzed?

•Describe the differences between the business processes before and after the BPR. System thinking (interactive

factors focusing)

Information system five components framework

•Describe the five components of the IS related to the case you analyzed or your project.

•Discuss the possible improvement of the IS components related to your project or the case you analyzed.

•What were the costs and benefits involved in your project or the case you analyzed? Information resources

management factors

•Discuss IT ethics involved in your project or the case you analyzed.

•Discuss the social and global issues related to the IT/IS in your project or the case you analyzed.

•Discuss information security and risk issues related to the IT/IS in your project or the case you analyzed.

A case analysis report should be organized by sections: instruction, analysis, thinking reflection, and conclusion or summary. In the analysis section, students discuss the text-book questions to understand the context and major issues related to the case. In the reflection section, students an-swer thinking queries. Students are encouraged to integrate other relevant cases learned from any courses or their own work experiences for the reflective thinking. Reflection es-say writing requests students to answer thinking queries for specific MIS topics covered by the course, such as ubiqui-tous computing and IS outsourcing. Thinking queries call for expression of thinking stream pertinent to the queries. An es-say should have a comprehensible introduction, paragraphs of viewpoints, and an assertive conclusion or summary. It should reflect applications of thinking models and provision of facts. Students are also encouraged to express their own experiences related to those thinking queries. References and citations must be used in the essay. Self-evaluation of higher order thinking is a free-format reflection report that provides an opportunity for a student to describe the objectives of higher order thinking and progress toward achieving the

ob-jectives, as well as her or his experience in conducting higher order thinking.

Assessment of Higher Order Thinking

An assessment process of higher order thinking in this course is characterized by measurable learning outcomes of higher order thinking and assessment instruments.

Measurable learning outcomes of higher order think-ing. Traditionally, the overall learning goals of this course emphasize course contents and lower order thinking (i.e., knowing and understanding). For the purpose of assessment of higher order thinking, the goals were specified to be the learning outcomes of higher order thinking. The measurable learning outcomes of higher order thinking for this course are represented in the following rubric.

Instruments of assessment and an example of as-sessment. The effectiveness of higher order thinking is the key criterion for evaluation of the teaching approach.

TABLE 2

Rubric of Higher Order Thinking for the Course

Performance

Higher order thinking Poor Excellent

Paradigm learning outcomes 0. . .100

Judgment •Analyzing why the IS succeeds or fails in the organization

•Assessing how the IT/IS strategies fit the business strategy of the organization

•Analyzing how the IS can be useful for decision making in the organization Planning •Planning business process re-engineering through IT

•Designing IS development process

Multiple perspectives •Evaluating cause and effect relationships between the IS components

•Identifying and evaluating social and organizational factors and their interrelationships in IS/IT applications

Although it is difficult to find a practically applicable ob-jective measure of the effectiveness of higher order thinking which involves complex human brain activities, there are two subjective measures that have been used for evaluation of this teaching approach.

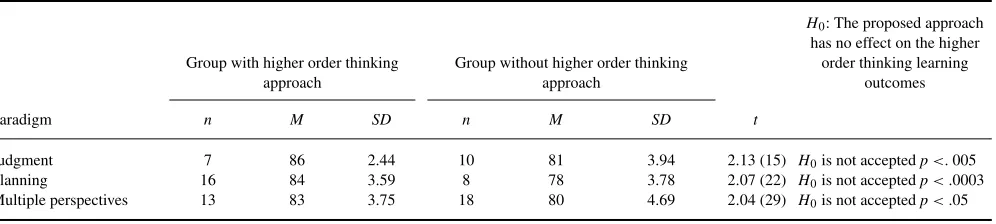

1. The teaching approach was evaluated on the basis of a comparison of the quality of case analysis reports that were written by two contrast groups of students (i.e., one group used the proposed approach and the other was not exposed to the approach). Thirty-six as-signments with the top grades in each group were ex-amined by the instructors. These case analysis reports addressed diverse cases even from different textbooks. Hence, each case analysis report was assessed against the most relevant criteria in the higher order thinking rubric in Table 2 and received average score if multiple criteria were applied. Table 3 shows that the group used the proposed higher order thinking approach outper-formed the other group in all three categories of higher order thinking learning outcomes for this course. 2. The teaching approach was also evaluated on the basis

of students’ self-evaluation reports on the approach. Fifty-two self-evaluation reports were analyzed using the manual qualitative analysis method. Overall, stu-dents’ feedback was positive. The following most com-pelling facts appeared in at least 26 of the 52 reports.

• Students did not know the difference between lower or-der thinking (e.g., memorizing) and higher oror-der thinking before learning this approach.

• Students consider that the three higher order thinking paradigms are new to them and are useful for understand-ing higher order thinkunderstand-ing in the business discipline.

• Students believe that the model-directed approach to teaching and learning higher order thinking is a good ap-proach.

• Students believe that the rubric of higher order thinking for this course is well connected with the three higher order thinking paradigms and the thinking models.

• Students recognize that the higher order thinking com-ponent of the course drive them to think more and think deeper.

While realizing that further independent evaluation stud-ies need to be done, we are convinced that this teaching method does help students develop higher order thinking skills.

DISCUSSION

It has been our experience that although the flexible nature of teaching accommodates differing approaches to higher order thinking and allows instructors to set teaching–learning strategies on their own, the model-directed method is a tool

TABLE 3

A Comparison of the Quality of Case Analysis Reports

Group with higher order thinking approach

Group without higher order thinking approach

H0: The proposed approach has no effect on the higher

order thinking learning outcomes

Paradigm n M SD n M SD t

Judgment 7 86 2.44 10 81 3.94 2.13 (15) H0is not acceptedp<. 005

Planning 16 84 3.59 8 78 3.78 2.07 (22) H0is not acceptedp<.0003

Multiple perspectives 13 83 3.75 18 80 4.69 2.04 (29) H0is not acceptedp<.05

TEACHING HIGHER ORDER THINKING 213

for teaching higher order thinking in the introductory MIS course. The following primary lessons have been learned from our practices during the past three years.

1. To avoid unsubstantiated thinking, we need instru-ments for teaching higher order thinking. We are con-vinced that the six models were instruments for foster-ing students’ higher order thinkfoster-ing in the introductory MIS course although few instruments are found in the literature. The model-directed method made multiple teaching modules (e.g., lecture, case analysis, essay writing) and assignments cohesive in terms of reflec-tion.

2. The model-directed method is also a tool for coordi-nating multiple instructors and multiple sections of this course to meet the uniform course objectives of higher order thinking.

3. Generally, teaching higher order thinking through models is a challenging task. It involves several steps of preparation, including generalization of thinking paradigms, identification of models, and design of typ-ical thinking queries. The most demanding activities on the teacher’s side include the articulation of work-specific thinking queries for individual student’s work and the intensive assessment workload. When a class size was large, time constraints could diminish work-specific thinking queries.

Some of the drawbacks of the approach to teaching and learning higher order thinking were observed as well. First, teaching higher order thinking takes more time from the instructor. Preparation of thinking queries and assessing re-flective writing are time consuming. Second, it is difficult to conduct pre- and posttests to prove that the improvement of higher order thinking has occurred in the classroom setting, although it is possible for laboratory experiments. Third, it is always a demanding task to make a balance between higher order thinking and course contents for the limited class time.

CONCLUSION

One of the most important aspects of effective business ed-ucation is to help business students to develop higher order thinking skills. Students must develop thinking skills in all higher order thinking aspects in order to meet challenges of the fast changing world. Educators need to have a greater understanding of higher order thinking schemes in order to design innovative curricula that emphasize students’ higher order thinking. We discussed major higher order thinking paradigms in general as well as in the business disciplines and proposed a model-directed method of teaching higher order thinking and presents an example of teaching higher order thinking in our introductory MIS course. Our practical

experiences have indicated that the model-directed method is useful for teaching higher order thinking. An expansion of this study should examine an expanded sample size of busi-ness courses to validate the impact of this teaching–learning approach on students’ development of higher order thinking skills.

REFERENCES

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (2003).Eligibility procedures and standards for business accreditation. Tampa, FL: Author. Braun, N. M. (2004). Critical thinking in business curriculum.Journal of

Education for Business,79, 232–236.

Checkland, P. (1981).Systems thinking, systems practice.New York, NY: Wiley.

Claywell, G. (2001).The Allyn and Bacon guide to writing portfolios. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Crittenden, V., & Woodside, A. (2007). Building skills in thinking: Toward a pedagogy in metathinking.Journal of Education for Business,82, 37– 43.

Dunne, D., & Martin, R. (2006). Design thinking and how it will change management education: An interview and discussion.Academy of Man-agement Learning & Education,5, 512–523.

Ericsson, K. A., & Smith, J. (1991).Toward a general theory of expertise: Prospects and limits. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Fisher, A. (2001).Critical thinking: An introduction. Cambridge, England:

Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Gharajedaghi, J. (1999).Systems thinking: Managing chaos and complexity. Boston, MA: Butterworth Heinemann.

Ives, B., Valacich, J. S., Watson, R. T., Zmud, R. W., Alavi, M., Baskerville, R.,. . .Whinston, A. B. (2002). What every business student needs to know about information systems.Communications of the Association for Information Systems,9, 467–477.

Jenkins, E. K. (1998). The significant role of critical thinking in predicting auditing student’s performance.Journal of Education for Business,73, 274–279.

Kida, T. (2006).Don’t believe everything you think: The 6 basic mistakes we make in thinking. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

McEwen, B. C. (1994). Teaching critical thinking skills in business educa-tion.Journal of Education for Business,70, 99–104.

Page, D., & Mukherjee, A. (2007). Promoting critical-thinking skills by using negotiation exercises.Journal of Education for Business,82, 251– 257.

Peach, B. E., Mukherjee, A., & Hornyak, M. (2007). Assessing critical thinking: A college’s journey and lessons learned.Journal of Education for Business,82, 313–320.

Perkins, D., Jay, E., & Tishman, S. (1993). Introduction: New conceptions of thinking.Educational Psychologist,28(1), 1–5.

Rainer, R. K. Jr., & Turban, E. (2009).Introduction to information systems

(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

Senge, P. M. (1996). Systems thinking.Executive excellence,13(1), 15–16. Simon, H. A. (1976).Administrative behavior(3rd ed.). New York, NY:

The Free Press.

Simon, H. A. (1996).The sciences of the artificial(3rd ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Snapp, J. C., & Glover, J. A. (1990). Advance organizers and study questions.

Journal of Educational Research,83, 266–271.

Stephens, C., & O’Hara, M. (2001). The core information technology course at AACSB schools: Consistency of chaos?Journal of Education for Busi-ness,76, 181–184.

Zubizarreta, J. (2004).The learning portfolio: Reflective practice for im-proving student learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.