3.2.1 Questionnaire ……… 90

Appendix 3.3 Guide for Interview with the Faculty’s Management (in Indonesian) ……….. 215

Appendix 3.5 Samples of the Results of Interview with the Faculty’s

Management ……….. 229 Appendix 3.6 Samples of the Fieldnotes (Observation in the Classroom) …..…

239

CURRICULUM VITAE ……….. 248

LIST OF TABLES

Page Table 2.1 Twenty Principles of Language Teaching (Nation & Macalister, 2010) ... 61 Table 2.2 Content and Sequencing Guidelines (Nation & Macalister, 2010) ……….. 65 Table 2.3 Format and Presentation Guidelines (Nation & Macalister, 2010) ……… 68 Table 2.4 Conditions and Activities for the Four Strands

Table 3.2 Distribution of Instructor’s Teaching Load ………. 87

Table 3.3 Structure of the Questionnaire ……….. 93

Table 4.1 Students’ Responses on the Syllabus ………. 112

Table 4.2 Students’ Responses on the Instructional Materials ……… 119

Table 4.3 Instructors’ Academic Qualifications ………

121

Table 4.4 Students’ Responses on the Teaching and Learning Activities ………… 124

Table 4.5 Final Grade Conversion ……….

126

Table 4.6 Objective Profile of the Students ………..

162

Table 4.7 Subjective Profile of the Students ………. 162

Table 4.8 Wants of the Students ………...

165

Table 4.9 Necessities of the Course ……….

166

Table 4.10 Learning Preferences of the Students ………. 167

Table 4.11 Lacks of the Students ……….. 168

Table 4.12 Environment Constraints and Effects ……….. 169

Table 4.13 Target Needs ………. 170

Table 4.14 Learning Needs ……….. 171

Table 4.15 Syllabus of the Proposed English Course ………... 175

LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 2.1 ESP Classification by Experience (Robinson, 1991: 3-4) ……….. 16

Figure 2.2 Simplified Tree of ELT (cf. Hutchinson & Waters, 1987: 17) ………... 17

Figure 2.3 A Synthesized Tree of ELT ………... 19

Figure 2.4 Materials Design Model (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987: 109) ………… 35

Figure 2.5 Factors Affecting ESP Course Design (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987: 22) 47

Figure 2.6 Connection between Curriculum and Syllabus (Dubin & Olshtain (1986: 43) ………. 50

Figure 2.8 Components of a Communicative Curriculum

(Dubin & Olshtain (1986: 68) ………...…… 52

Figure 2.9 Nation & Macalister’s (2010) Curriculum Design Model ………..…... 55

Figure 4.1 Classroom Setting (Reece & Walker, 2003) ……….. 115

Figure 4.2 A Summary of the Course Design Process ………. 180

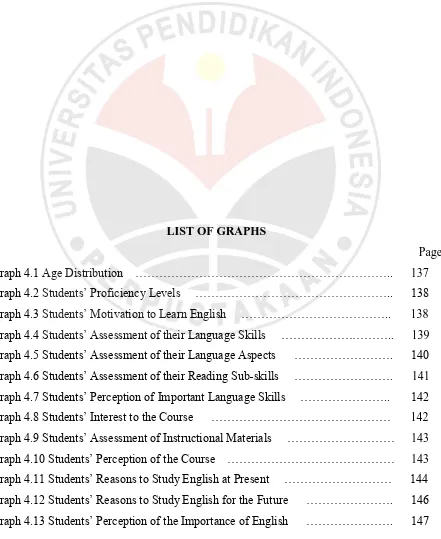

LIST OF GRAPHS Page Graph 4.1 Age Distribution ……….. 137

Graph 4.2 Students’ Proficiency Levels ……….. 138

Graph 4.3 Students’ Motivation to Learn English ………..

138

Graph 4.4 Students’ Assessment of their Language Skills ……….. 139

Graph 4.5 Students’ Assessment of their Language Aspects ………. 140

Graph 4.6 Students’ Assessment of their Reading Sub-skills ………. 141

Graph 4.7 Students’ Perception of Important Language Skills ……….. 142

Graph 4.8 Students’ Interest to the Course ……… 142

Graph 4.9 Students’ Assessment of Instructional Materials ………

143

Graph 4.10 Students’ Perception of the Course ……… 143

Graph 4.11 Students’ Reasons to Study English at Present ……… 144

Graph 4.12 Students’ Reasons to Study English for the Future ………. 146

Graph 4.14 Importance of Oral Accuracy ……….. 148

Graph 4.15 Frequency of Writing Tasks ……….. 148

Graph 4.16 Students’ Immediate Future Needs ……….. 149

Graph 4.17 Students’ Learning Places Preference ……….. 150

Graph 4.18 Students’ Learning Styles Preference ………

151

Graph 4.19 Students’ Learning Activities Preference ……….. 152

Graph 4.20 Students’ Preference of Instructors ………

153

Graph 4.21 Students’ Language Skills Preference ……… 154

Graph 4.22 Students’ Correction Preference ………

154

Graph 4.23 Students’ Learning Media Preference ………..

155

Graph 4.24 Learning Media Accessibility ……….. 156

Graph 4.25 Students’ Learning Time ……….. 156

Graph 4.26 Students’ Use of Supplementary Materials ……… 157

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

This chapter describes the background of the research, the research questions, the research purposes, and the research significance.

1.1Background

The background includes the status and functions of English in Indonesia, the teaching of English in all levels of education, and the reasons for choosing the research topic.

English is one of the languages widely spoken in the world. Graddol (1997: 10) mentions that there are three levels of English-speakers: (a) the first-language speakers to the number of 320-380 million, (b) the second-language speakers to the number of 150- 300 million, and (c) the foreign-language speakers to the number of 1 billion. Tonkin (2003: 16) assumes that the only people who think that one can conduct all of one‟s affairs in this world through the medium of a single language are speakers of English. They feel as they do because of the notable spread of the English language in modern times to almost all corners of the globe and almost all domains of human endeavor. English is also the world‟s most studied language: there are hundreds of millions of people across the world

who are studying or have studied the language.

language has not, however, been officially stated by a decree although the 1993 State Policy Guidelines explicitly asks for the improvement of foreign language mastery to meet the needs of globalization.

Determining the standing of a language in a community refers to status planning which is part of language planning. Status planning refers to the allocation of languages or language varieties to given functions, e.g. medium of instruction, official language, vehicle of mass communication (Cooper, 1989: 32). Language allocation is “authoritative decisions to maintain, extend, or restrict the range of uses (functional range) of a language in particular settings” (Gorman, 1973: 73). Stewart (1968) provides a list of language

functions as targets of status planning: official language, provincial language, national language, international language, capital language, ethnic/group language, educational language, school subject, literary language, and religious language. The Indonesian Center for Language Cultivation and Development (Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa), however, differentiates language status from language function. Language status

refers to the relative status of language as a system of cultural value symbols formulated on the basis of social values related to the language; language function refers to the role of language in the community of language users (Alwi & Sugono, 2000: 219).

90% of the Indonesian people are Moslems, and (c) Japanese, German, French, Chinese, etc. which influence certain aspects of life, such as commerce and communication.

As the primary foreign language, English has the following functions in Indonesia (Alwi & Sugono, 2000: 221):

(1) English is a language for wider communication (among nations) in all aspects of life. The decision to choose English to become the language for wider communication is based on the following reasons (Huda, 2000: 68): (a) English has a very good internal linguistic weight, (b) there is a large number of speakers of English as the first, second and foreign language, (c) English has the widest geographic distribution, (d) English is widely used in the fields of science, technology, culture, and politics, (e) English-speaking countries dominate in the world‟s economy, politics, and culture.

(2) English is a tool for making use of science and technology development to accelerate the national development. Since most of the scientific books are written in English, Indonesian people who know English could absorb, transfer, make use of, and distribute science and technology progress to improve the quality of the nation. English mastery will subsequently improve the quality of human resources. English competence, once attained, becomes a highly effective tool of intellectual discourse and learning of the world‟s knowledge (Gonzales, 2003).

1989: 134). English will help develop Indonesian to become a standardized and modern language in terms of not only lexis but also grammar. Incorrect word formation, double subordinating conjunctions, dangling structure, etc. can be avoided.

Considering the functions of English in Indonesia, the government has emphasized the importance of English language teaching in the country. The Department of National Education with regard to the Competence-Based English Curriculum states the rationale of the curriculum as follows (Departemen Pendidikan Nasional, 2001, translated into Indonesian in Emilia, 2005: 3):

As a language which is used by more than half of the world‟s population, English is ready to carry out the role as the global language. Apart from being the language for science, technology and arts, this language can become a tool to achieve the goals of economy and trade, relationship among countries, socio-cultural purposes, education and career development for people. The mastery of English can be considered as a main requirement for the success of individuals, the society and the nation of Indonesia in answering the challenges of the time in the global level. The mastery of English can be acquired through various programs, but the program of English teaching at schools seems to be the main facility for Indonesian students.

acquisition of the target language (English) need to be accorded a special importance, and (2) The facilities and human resources for the teaching of English in tertiary education need to be developed to strengthen the position of the language as an effective tool in the international constellation.

English as a foreign language in Indonesia is taught at all levels of education. The department in charge of teaching or education is the Ministry of National Education and Culture. The following are some of the English language acquisition policies in primary, secondary, and tertiary education

transactional, formal and informal, discourses in the forms of recount, narrative, procedure, descriptive, news item, report, analytical exposition, hortatory exposition, spoof, explanation, discussion, and review, in everyday life contexts; (c) the students understand written interpersonal and transactional, formal and informal, discourses in the forms of recount, narrative, procedure, descriptive, news item, report, analytical exposition, hortatory exposition, spoof, explanation, discussion, and review, in everyday life contexts; and (d) the students express written interpersonal and transactional, formal and informal, discourses in the forms of recount, narrative, procedure, descriptive, news item, report, analytical exposition, hortatory exposition, spoof, explanation, discussion, and review, in everyday life contexts.

In tertiary education, Paragraph 1 Article 7 of the Decree of the Ministry of National Education No. 232/U/2000 on the guideline for tertiary education curriculum and students‟

education for undergraduate students should include such subjects as religious education, civics education, Indonesian, and English. Therefore, English is one of the subjects taught in tertiary education.

English language teaching in tertiary education is not promising (Alwasilah, 2007: 58). Given that English at secondary schools is designed to equip students with basic knowledge and skills, college English should aim at building academic or study skills which can help students to digest textbooks and references as an integral part of developing professionalism and specialization of their choice. In other words, college English should be taught as English for Specific Purposes (ESP) or English for Academic Purposes (EAP), not English for General Purposes (EGP). From a survey, Alwasilah (2004 & 2007) found some weaknesses of the English course at the college level: (1) No needs analysis is conducted so that the course does not meet students‟ expectations, (2) The class is

relatively big and heterogeneous, (3) The course is taught by young inexperienced instructors, (4) There is a repetition of what has been taught at secondary schools, (5) There is no selection and classification based on competencies and students‟ needs, (6)

Training and Education, it is a compulsory 2-credit course for the freshmen in the first or second semester. This discouraging practice motivated the researcher to explore and improve the conditions. Therefore, he proposed to conduct a qualitative study of the English language teaching at the faculty in order to describe the conditions of the English course, to find out the students‟ needs, and ultimately to design a better course.

1.2 Research Questions

There has been a growing trend in course design with the focus shifting from teacher-centered to learner-teacher-centered activities in recent years. In this regard, a lot of attention is being given to need-based language courses. The emergence of English for Specific Purposes (ESP) contributes to this trend. ESP is “an approach to language teaching which aims to meet the needs of particular learners” (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987: 21). Since ESP is driven by learner needs, the first step for ESP curriculum design is to identify the specific needs of learners. Needs analysis, therefore, comes into the picture.

on the intuitions and experience of the teaching personnel. Atai (2000: 30) believes that curriculum development should not take “a one-way top-down approach”.

To help design a better language course, this research which took place at the Faculty of

Teacher Training and Education of a state university in South Sumatra did a needs analysis through the implementation of questionnaire, interview, observation, and review of documents. In this respect, the problems of the research could be formulated into the following questions:

(1) How is the present practice of English language teaching at the institution in terms of such aspects as institutional goals, class management, instructional materials, instructors, teaching methodology, and evaluation?

(2) What are the students‟ needs and the faculty‟s expectations of the English course? (3) What course design can be proposed for the English language teaching at the institution

on the basis of the expected goals?

1.3 Research Purposes

The goals of the research were consequential, which means that the achievement of the previous purpose would be the basis of reaching the next purpose.

The second purpose of the research was to find out the students‟ needs and the faculty‟s expectations of the English course through needs analysis. The needs analysis for the students by using a questionnaire included target situation analysis, present situation analysis, strategy analysis, means analysis, and deficiency analysis. The interview with the instructors and the faculty‟s management provided the information about the importance of the English course, the objectives of the course, the educational backgrounds of the instructors, the instructional materials, the evaluation system, and the facilitating and inhibiting factors in the implementation level.

The findings from the questionnaire and those from the interview, observation, and review of documents would become the basis of designing a better course for the students.

1.4 Research Significance

Since the institution has never evaluated the English course before, this research would be the first empirical study carried out in that course. This research would therefore contribute to the professional sources in English language teaching at the institution in particular and English language teaching in higher education in general. Several variables should be put into consideration in the language teaching, such as the status of the course, the number of credits allocated, the class size, the students‟ English proficiency levels at

present, the students‟ interests, the course objectives, the instructional materials, the

evaluation system, and the instructors.

on other faculties in the university are recommended as the conditions at other faculties may be quite different.

This research would also show the importance of needs analysis in the process of designing a language course. There was never before a formal needs analysis conducted by the university‟s language institute as the coordinator of the English course. The course was

designed on the basis of the intuitions and experience of the teaching staff. Language courses or programs developed by taking into account learner needs tend to achieve better instructional outcomes.

In relation to the needs analysis, this research would indicate the involvement of stakeholders of the English course. Besides the students and the university‟s language

institute, the stakeholders include the instructors, the heads of study programs, the heads of departments, the associate dean for academic affairs, and the dean of the faculty. The participation of the faculty‟s management (i.e. in determining the direction of the course

CHAPTER III

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This chapter discusses the research methodology which includes the research design, the data collection, the data analysis, and the limitations of the present study. The research design provides the theoretical framework on which the research is based on, the purposes of the research, and the research site and participants.

3.1 Research Design

This present study is in the domain of applied linguistics, especially in ESP. ESP is an approach to language teaching which aims to meet the needs of particular learners. Some experts, including McDonough (1984), Hutchinson and Waters (1987), Robinson (1980 & 1991), Jordan (1997), Dudley-Evans and St John (1998), agree that the key stages in ESP are needs analysis, course (and syllabus) design, materials selection (and production), teaching and learning, and evaluation. The five stages can actually be contracted into three phases: needs analysis, course design, and application. ESP therefore begins with

identifying learners‟ needs, and then designing a course on the basis of the needs, and

finally the practical application of the course design. Learners‟ needs may include objective and subjective needs (Brindley, 1989; Robinson, 1991) or perceived and felt needs (Berwick, 1989; Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998). Course design is the process by

which the raw data about learners‟ needs are interpreted in order to produce an integrated

accordance with the syllabus, to develop a methodology for teaching those materials and to establish evaluation procedures by which progress towards the specified goals will be measured. The course design is based on the principles suggested, among others, by Taba (1962), Dubin & Olshtain (1986), Hutchinson & Waters (1987), Robinson (1991), Graves (1996, 2000), Jordan (1997), Diamond (2008), and Nation & Macalister (2010).

The ultimate aim of this present study is to propose a design for the English course at the university level. To achieve the intended aim, the researcher would do three main sets of activities. First, this present study began with library research to find out the concept of ESP and to review literature on ESP and previous related studies. Second, on the basis of the theory, needs analysis was conducted in order to identify the needs of the students and other concerned parties including the language instructors, the heads of departments and study programs, the heads of the faculty, and the head of university‟s language institute. Third, the results of needs analysis would be analyzed and interpreted to produce a course design appropriate for the students.

This present study used questionnaire, interviewing, observation, and review of documents as the data collection methods, as suggested by Patton (1990), Brannen (1992), Marshall & Rossman (1995), Maxwell (1996), Bogdan & Biklen (1998), Wray et al. (1998), Glesne (1999), and Silverman (2005). The data were analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively. Descriptive statistics were used to present the data quantitatively in the form of percentage.

Faculty of Agriculture, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Faculty of Social and Political Science, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Faculty of Computer Science, and Faculty of Public Health.

Due to easy accessibility and institutional support, the researcher focused the study on the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education. The faculty has three departments with twelve study programs: Department of Language and Arts Education with two study programs (Indonesian Language and Literature Education Study Program, and English Education Study Program), Department of Social Sciences Education with three study programs (Civics Education Study Program, History Education Study Program, and Economics/Accounting Education Study Program), Department of Mathematics and Natural Sciences Education with four study programs (Mathematics Education Study Program, Physics Education Study Program, Chemistry Education Study Program, and Biology Education Study Program), and three other separate study programs (Health and Physical Education Study Program, Guidance & Counseling Education Study Program, and Mechanical Engineering Education Study Program.

faculty opens student enrollment for both campuses; therefore, each study program may have one class of students on Indralaya main campus and one or more parallel classes on Palembang campus.

At the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, English is a compulsory 2-credit course for the freshmen in the first or second semester, except for the students of English

Education Study Program; and the course is coordinated by the university‟s Language

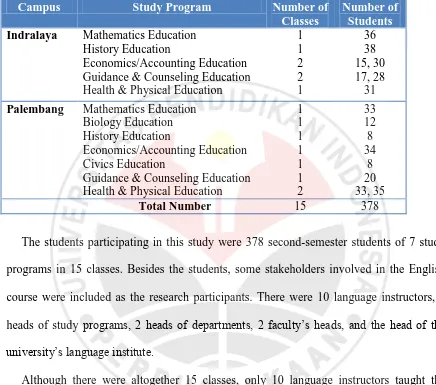

Table 3.1 Number of Classes and Students heads of study programs, 2 heads of departments, 2 faculty‟s heads, and the head of the

university‟s language institute.

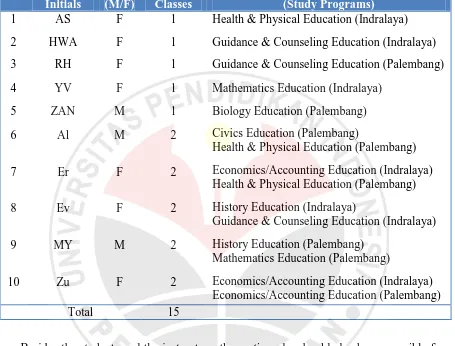

Although there were altogether 15 classes, only 10 language instructors taught the classes. Five instructors taught one class each whether in Indralaya or in Palembang. Five other instructors taught 2 classes each, whether two Indralaya classes or two Palembang classes or one Indralaya class and one Palembang class. Table 3.2 shows the distribution of

Table 3.2 Distribution of Instructor‟s Teaching Load

Besides the students and the instructors, the parties who should also be responsible for determining the objectives and designing the courses conceptually at the faculty are the

faculty‟s head, the heads of departments, the head of study programs, and the head of

language institute (in case of language courses). The persons in the faculty‟s management

included in this study as the participants are as follows:

- Dean of the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education - Associate Dean for Academic Affairs

- Head of the University‟s Language Institute - Head of Social Sciences Education Department

- Secretary of Mathematics & Natural Sciences Education Department - Head of Mathematics Education Study Program

- Head of History Education Study Program

- Head of Economics/Accounting Education Study Program - Head of Civics Education Study Program

- Head of Guidance & Counseling Education Study Program - Head of Health & Physical Education Study Program

3.2 Methods of Data Collection

Qualitative research method was selected for this study. Questionnaire, interviewing, observation, and review of documents were the research tools for data collection, as suggested by Johnson (1992), Nunan (1992), Marshall & Rossman (1995), Maxwell (1996), McDonough & McDonough (1997), Bogdan & Biklen (1998), Creswell (1998), Wray et al. (1998).

Triangulation refers to collecting information from a diverse range of individuals and settings, using a variety of methods to corroborate each other (Denzin, 1978; Patton, 1990; Glense & Peshkin, 1992; Cohen & Manion (1994); Marshall & Rossman, 1995; Mason, 1996; Bogdan & Biklen (1998). The term which originally comes from the application of trigonometry to navigation and surveying was first borrowed in the social sciences to convey the idea that to establish a fact you need more than one source of information. Typically, this process involves corroborating evidence from different sources to shed light on a theme or perspective (Creswell, 1998: 202). Many sources of data are better in a study than a single source because multiple sources lead to a fuller understanding of the phenomena being studied. According to Alwasilah (2006), triangulation of interview and observation is needed to provide a complete and accurate account of an event. Furthermore, Maxwell (1996: 76) states:

Observation often enables you to draw inferences about someone‟s meaning

data. This is particularly true of getting at tacit understandings and

theory-in-use, as well as aspects of the participants‟ perspective that they are

reluctant to state directly in interviews. … Conversely, interviewing can be a valuable way (the only way, for events that took place in the past or ones to which you cannot gain observational access) of gaining a description of actions and events. These can provide additional information that was missed in observation and can be used to check the accuracy of the observation.

In this research, the triangulation of different data-collection techniques (questionnaire, interviewing, observation, and review of documents) was used to mutually corroborate or verify the data obtained from the different instruments in order to answer the research questions. Denzin (1978) calls this type of triangulation as methodological triangulation, the use of different methods on the same object of study.

With regard to the second research question, the techniques of data collection were questionnaire and interviewing. The questionnaire was used to collect the data related to

the students‟ needs analysis which includes target situation analysis, present situation

analysis, strategy analysis, and deficiency analysis. The participants (the head of the language institute, the course coordinator, the dean of the faculty, the associate dean for academic affairs, the heads of departments, the heads of study programs, and the course instructors) were interviewed individually to find out their expectations of the course. In sum, the data were collected through (a) a questionnaire given to 378 students in 15 classes, (b) interviews with the instructors, the heads of departments/study programs, the

faculty‟s heads, the language institute head, (c) observations in the classroom, and (d)

review of the documents. The following subsections describe the research instruments in detail

3.2.1 Questionnaire

slot/box. The answers from the fixed-choice questions may lend themselves to simple tabulation. The present questionnaire is a modification from the one designed by Papageorgiou (2007) for the respondents of Hellenic Air Force Officers at the School of Foreign Languages, in the Hellenic Air Force Academy, Greece, in order to find out their English language needs. Some items in the previous questionnaire were deleted, added, and/or modified to suit the conditions of the present study. For example, the items in the previous questionnaire on nationality, English language certification, mastery of other foreign languages, social relations within occupational contexts, and briefing/debriefing of flights, were deleted in the present questionnaire. The items on the present English course were added in the present questionnaire. In some items, promotion was changed into examination requirement, understanding foreign pilots on the radio into understanding

English broadcasting in the present questionnaire.

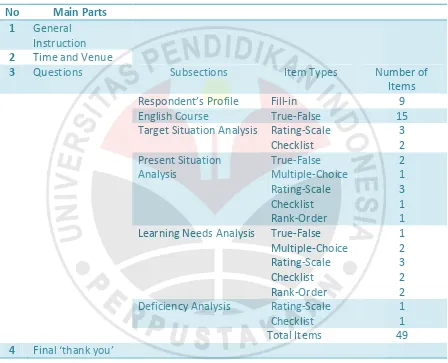

The present questionnaire (Appendix 3.1) has 4 main parts and consists of 8 pages of A4 size paper. The main parts of the questionnaire are as follows:

• General Instruction, which gives the title of the study, the purposes of the questionnaire, and the request to give brief but clear answers

• Time and Venue, which asks the respondents to fill in the day/date, time and venue, when

and where they are asked to fill out the questionnaire

• Questions, which consist of six categories: respondent‟s profile, English course, target

situation analysis, present situation analysis, learning needs analysis, deficiency analysis

• Final „thank you‟, which thanks the respondents for their time and information, and

requests the respondents to spare their time for further information if needed.

the deficiency analysis. The respondent‟s profile includes the name, age, sex, study

program, department, semester, senior high school, TOEFL prediction score, and interest to learn English. The English course subsection includes 5 items about what the instructor did at the beginning of the course, 5 items about the instructional materials, and 5 items about the teaching and learning activities. All the questions on the English course are true-false items. The target situation analysis subsection has 3 rating-scale items and 2 checklist

items, asking about the students‟ reasons to study English for the future, their perception of

the importance of English, the importance of oral accuracy, how often they need to write reports/technical documents/papers in English, and their immediate future needs. The present situation analysis subsection has 2 true-false items, 1 multiple-choice item, 3 rating-scale items, 1 checklist item, and 1 rank-order item, asking about the students‟ assessment of their language skills, language aspects, reading skills, their perception of important language skills, how they like to participate in the English course, whether the English course gives them some new knowledge, how they like the instructional materials, their reasons to study English at present. The learning needs analysis subsection has 1 true-false item, 2 multiple-choice items, 3 rating-scale items, 2 checklist items, and 2 rank-order items, asking about the students‟ learning preferences of place, activity, instructor, language skills, feedback, media, and time. The deficiency analysis subsection has 1 rating-scale item and 1 checklist item, asking about the students; learning difficulties and their needs for practice.

subsection aims at partly finding out the present practice of the course in order to answer the first research question. Table 3.3 shows the structure of the questionnaire.

Table 3.3 Structure of the Questionnaire

No Main Parts

1 General Instruction

2 Time and Venue

3 Questions Subsections Item Types Number of

Items

manager at the School of Teaching and Learning, College of Education and Human Ecology, the Ohio State University, Columbus, U.S.A.

The students filled out the questionnaire in the classroom during the class. Some instructors allowed this data collection at the beginning of the class and continued the teaching and learning activities afterwards, while the other instructors preferred to have class first and then allocated some time for this activity towards the end of the class. The time needed for the students to fill out the questionnaire was 30 minutes on the average.

3.2.2 Interview

An interview is a purposeful conversation, usually between two people but sometimes involving more, that is directed by one in order to get information from the other (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998: 93). The interview used in this study is the structured interview. In this type of interview, “the agenda is totally predetermined by the researcher, who works through a list of set questions in a predetermined order” (Nunan, 1992: 149). The data collection through questionnaire and interview was administered with a high degree of explicitness which involved the use of formal and structured types of questions formulated in advance (Seliger & Shohamy, 1989; Sommer & Sommer, 1991). Although an interview guide is employed, the interviewer has considerable latitude to pursue a range of topics and offer the subject a chance to shape the content of the interview.

by Kusni (2004) for his study. For example, the items in the previous interview guide for the instructors on technical vocabulary, language-skills focus, and instructor‟s professionalism, were deleted in the present interview guide. The items in the previous

interview guide for the faculty‟s management on syllabus preparation and student

assessment, were deleted; however, the item on whether the course should be ESP or EAP was added in the present interview guide.

The interview guide for the instructors has 4 main parts and consists of 4 pages of A4 size paper. The main parts of the interview guide for the instructors are as follows:

• Introduction, which gives the title of the study, the purpose of interview, and the request

to give clear answers

• Time and Venue, which provides the day/date, time and venue, when and where the

interview is taking place

• Questions, which consists of ten categories: respondent‟s profile, importance of the

English course, students‟ proficiency, course objectives, needs analysis, course preparation, instructional materials, teaching and learning activities, evaluation, and facilitating/inhibiting factors and suggestions

• Final „thank you‟, which thanks the respondent for the time and information, and requests

the respondent to spare his/her time for further information if needed.

The questions on several topics in the interview guide provide some information about the respondents and their knowledge and opinions of the English course. The respondent‟s profile gives the name, sex, age, field of study, educational background (undergraduate/master/doctor, place and year of graduation), experience in teaching the course, and special training. The importance of the English course includes the process and the parties in deciding the course as compulsory, and the importance of the course for the students in terms of language skills and aspects. The students‟ proficiency includes the

and aspects. The topic of course objectives provides the information of what the course objectives are, who determines the objectives, and whether 2 credit-hours is enough. The needs analysis includes, if there was one, who and how to conduct it, and what the results were. The course preparation includes who prepared the syllabus, whether the students had the syllabus at the beginning of the course, and whether the instructor reviewed or evaluated the syllabus. The topic of instructional materials includes the kinds of materials and the focus of the materials on certain language skills or aspects. The topic of teaching and learning activities gives the information of types of activities and assignments, and the

students‟ participation. The evaluation includes the students‟ assessment and course

evaluation (what aspects to evaluate, who evaluates, how to design the course). Finally, in the facilitating/inhibiting factors and suggestions, the instructors give their personal opinions and suggestions for the course at the implementation level.

The interview guide for the faculty‟s management has a similar format as that for the instructors. Similarly, the interview guide for the faculty‟s management has four main parts (Introduction, Time and Venue, Questions, and Final „thank you‟); however, some

topics and questions in the section „Questions‟ are different. The questions in the interview

guide for the faculty‟s management include nine categories: respondent‟s profile,

importance of the English course, students‟ proficiency, course objectives, needs analysis,

instructors, instructional materials, evaluation, and facilitating/inhibiting factors and

suggestions. Apart from the importance of the English course, students‟ proficiency,

also included; and the needs analysis also includes who should design the course and why.

In the respondent‟s profile, teaching experience and special training are excluded, but

employee‟s rank and position are included. In the evaluation, the students‟ assessment is

excluded as it is within the discretion of the instructors. The topic of instructors gives the information on the types and choice of instructors and the possibility of team teaching. Apart from the respondent‟s profile, there are 32 questions altogether in the interview guide for the instructors, and 30 questions in the interview guide for the faculty‟s management. However, it should be noted that not all the questions might be asked in the actual interview. For example, in some instances, when asked whether a needs analysis had been conducted for the course and the respondent answered „No‟, then the next questions

(„How was it conducted? What were the results?) would not be asked. When the

respondent answered „No‟ to the question „Has the course ever been evaluated before?‟,

then he/she would not be probed more deeply with the questions „What aspects were being

evaluated? Who were involved in the evaluation?‟. In other instances, another respondent

might answer a question at great length so that he/she would actually answer the next questions that would be asked to him/her.

The individual interviews with the respondents were usually based on an appointment. The interviews with the instructors took place outside the class in the lecturer room in

Indralaya and/or Palembang, and the interviews with the faculty‟s management took place

respondents at their ease to express themselves. The researcher took notes during the interview and completed the notes after the session. The time needed for the interview was 30 minutes on the average.

3.2.3 Observation

Observation refers to the collection of data without manipulating it; “the aim is to gather first-hand information about social processes in a naturally occurring context” (Silverman, 1993: 11); “the researcher simply observes ongoing activities, without making any attempt to control or determine them” (Wray et al., 1998: 186). Observation entails the systematic noting and recording of events, behaviors, and artifacts (objects) in the social setting chosen for study (Marshall & Rossman, 1995: 79). The observation used in this study is the non-participant observation in which the researcher makes no effort to have a

particular role, or the researcher is to be tolerated as an unobstrusive observer, „invisible‟

to the subjects. In this respect, the researcher is expected to observe or gather data without interfering in the ongoing flow of everyday events.

the researcher in the questionnaire session. All the observations took place within weeks after the students filled out the questionnaire. The researcher usually sat at the back of the classroom in a theatre-seating arrangement or at one corner in a u-shaped seating

arrangement. The researcher tried to be „invisible‟ to the instructor and students. During

the observation, the researcher took notes of what happened in the class. After the class, the researcher thanked the instructor and students, and completed the fieldnotes outside the class if necessary.

The results of observation are fieldnotes. Fieldnotes refer to the written account of what the researcher hears, sees, experiences, and thinks in the course of collecting and reflecting on the data in a qualitative study (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998: 107-108). Fieldnotes consist of two kinds of materials: descriptive and reflective. (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998; Creswell, 1998). The descriptive part of fieldnotes provides a word-picture of the setting, people, actions, and conversations as observed; the reflective part gives a more personal account of

the course of the inquiry, which captures the observer‟s frame of mind, ideas, and

concerns. The reflective part of fieldnotes is designated by the notation of “O.C.”, which stands for observer’s comment.

communicative features in Part B include the use of target language, information gap, sustained speech, reaction to code or message, incorporation of preceding utterance, discourse initiation, and relative restriction to linguistic form.

The fieldnotes, therefore, include the information about what the activity type was (lecture, discussion, roleplay, etc.), whether the teacher was working with the whole class and/or whether the students worked individually or in groups, whether the focus was on language form/function and who selected the topic, whether the students were involved in a certain language skill or a combination of skills, what types of materials were used, and what the seating arrangement was. The fieldnotes would partly answer the first research question on the present practice of the English course, especially on the aspects of teaching methodology, class management, and instructional materials. As the focus of the inquiry had been determined, the researcher would not seek to report „everything‟ in the fieldnotes. Wolcott (1990: 35) states that “the critical task in qualitative research is not to accumulate

all the data you can, but to „can‟ (get rid of) most of the data you accumulate. This requires

constant winnowing”. Winnowing the data refers to reducing the data to a small manageable set of themes to write into the final narrative.

3.2.4 Review of Documents

and documents may be analyzed to understand the participants‟ categories and to see how

these are used in concrete activities.

The documents collected in the present study include policy documents, syllabi and lesson plans, instructional materials, and tests and student test records. The documents

were obtained from the university‟s language institute as the coordinator of the English

course. All these documents could be classified as official institutional documents. There were no personal documents and popular culture documents.

Bogdan & Biklen (1998) classify documents into three main types: personal documents, official documents, and popular culture documents. Personal documents are those produced by individuals for private purposes and limited use, such as letters, diaries, autobiographies, family photo albums and other audio/visual recordings. Official documents are produced by an organization for record-keeping and dissemination purposes, such as memos, minutes of meetings, newsletters, policy documents, proposals,

students‟ records, brochures and the like. Popular culture documents are those produced for

commercial purposes to entertain, persuade, and enlighten the public, such as commercials, TV programs, news reports and audio/visual recordings.

The official institutional documents collected are as follows:

(a) the decree of the rector of the university on the organization and working hierarchy of University‟s Language Institute

(b) the decree of the rector of the university on the minimal TOEFL scores which should be achieved by the students at the faculties/programs of the university

(c) the syllabus for the students of natural sciences and the syllabus for the students of social sciences

(d) lesson plans for reading materials

(e) the two coursebooks used in the classroom

(h) the students‟ final grades for the English course in the even semester 2009/2010

3.3 Methods of Data Analysis

Data analysis is the process of bringing order, structure, and meaning to the mass of collected data (Marshall & Rossman (1995: 111). Analysis involves working with data, organizing them, breaking them into manageable units, synthesizing them, searching for patterns, discovering what is important and what is to be learned, and deciding what you will tell others (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998: 157). In general, the data of this present study were analyzed in three phases of data transformation advanced by Wolcott (1994): description, analysis, and interpretation. Wolcott (1990: 28) believes that a good starting point for writing a qualitative report is to describe the setting:

Description is the foundation upon which qualitative research is built ….

Here you become the storyteller, inviting the reader to see through your

eyes what you have seen…. Start by presenting a straightforward description of the setting and events. No footnotes, no intrusive analysis ─

just the facts, carefully presented and interestingly related at an appropriate level of detail.

The analysis procedure is the search for patterned regularities in the data. Analysis involves highlighting specific material introduced in the descriptive phase or displaying findings through tables, charts, diagrams, and figures. In the interpretation, the researcher goes beyond the database and probes “what is to be made of them” (Wolcott, 1994: 36),

and “draws inferences from the data or turns to theory to provide structure for his or her

interpretations” (Creswell, 1998: 153). Interpretive act is a process of bringing meaning to

meaning to those data and displays that meaning to the reader through the written report (Marshall & Rossman, 1995: 113).

The data analysis in this study was predominantly inductive and eclectic in nature. Inductive data analysis involves arguing from particular facts or data to a general theme or conclusion. The data analysis is eclectic in which the researcher analyzing the data employs an electric mix of the available analytical tools that best fit the data set under considerations. Teddie & Taskhakkori (2009: 252) state that researchers frequently gather information from a variety of sources; therefore, they often have to employ more than one type of analysis to accommodate the differences among the sources. Denzin & Lincoln (2005: 4) refer to qualitative researchers as bricoleurs, who employ a wide range of available data collection methodologies and analysis strategies.

The data obtained from the questionnaire were presented in tabulations. Dörnyei (2003: 14) states that the typical questionnaire, with most items either asking about very specific pieces of information or giving various response options for the respondent to choose from, will produce the data particularly suited for quantitative, statistical analysis. In this case, graphic formats such as frequency tables and graphs were used to display the descriptive statistics, as suggested by Strauss (1987), Miles & Huberman (1993 & 1994), and Creswell (1998). Marshall & Rossman (1995: 128) believe that data display could promote analysis and could also summarize the results of analysis.

observation data, and the data from documents were mutually corroborate to give a portrait of the present English course. Tables and graphs might be generated to display the data; however, the analysis would mostly be in descriptive narrative form. In the analysis, the researcher would also draw connections between the data and the theoretical framework. As for the data collected to answer the second research question on the students‟ needs, the questionnaire data were described in terms of the subcategories of needs analysis, namely the target situation analysis, the present situation analysis, the learning needs analysis, and the deficiency analysis. The needs analysis would include the interview data

from the instructors and faculty‟s management in order to find out the faculty‟s

expectations of the English course. As the interviews were structured with a list of set questions in a predetermined order, the data obtained might be presented quantitatively in numbers and/or qualitatively in narrative form.

The results of analysis and interpretation would be used as the basis of a course design proposed for the English language teaching at the faculty. The course design was based on the principles suggested, among others, by Taba (1962), Dubin & Olshtain (1986), Hutchinson & Waters (1987), Robinson (1991), Brown (1995), Graves (1996, 2000), Jordan (1997), Diamond (2008), and Nation & Macalister (2010).

3.4 Limitations of the Study

seven study programs which offer the course in the second semester, namely Mathematics Education, Biology Education, History Education, Economics/Accounting Education, Civics Education, Guidance & Counseling Education, and Health & Physical Education Study Programs. Although not all the freshmen were included in the study, the student participants of the seven study programs had represented the students of social sciences and natural sciences.

The study is also limited in terms of the research site in which the data was collected, that is the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, not including all the faculties of the university. The university has 10 faculties, namely Faculty of Economics, Faculty of Law, Faculty of Engineering, Faculty of Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Faculty of Social and Political Science , Faculty of Mathematics

and Natural Sciences, Faculty of Computer Science, and Faculty of Public Health. Besides the practical reasons of accessibility and institutional support for selecting the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, the exclusion of other faculties was based on objective reasons. Each faculty has its own characteristics and its own perspectives on the importance of English for its students. For example, the Faculty of Medicine allocates 6-credit hours for the English course and the minimal TOEFL-score requirement for its graduates is 450, while the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education provides only a 2-credit-hour English course and requires its graduates to have the minimal TOEFL-score of 400.

Lastly, the main limitation of the present study concerns the practical application of the course design as the end-product of the study. As discussed in the previous chapter, ESP

needs, and finally the application of the course design. Following the stages in ESP, this study began with identifying the specific needs of the students through needs analysis. The

needs analysis also included the faculty‟s views of the English course. Then, this study

CHAPTER V

CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS

This chapter gives the conclusions of the study and provides some suggestions to some parties responsible for planning and implementing the English course. The conclusions focus on the answers to the research questions or the purposes of the research. Suggestions are then given on the basis of the conclusions.

5.1 Conclusions

The purposes of this research are (1) to depict the existing conditions of the present English course, (2) to find out the students’ needs and the faculty’s expectations of the English course through needs analysis, and (3) to propose a better English course design based on the needs analysis. The findings of the research conducted through questionnaire, observation, interview, and documents review, give a portrait of the present English course and provide the information on the student profile, the target needs and learning needs, which becomes the basis for designing a new English course.

The following presents a summary of the main findings and then gives the conclusions of the study on the basis of the findings.

based on the students’ common cores, natural or social sciences. Assuming that the course

would improve the students’ skill to comprehend reading texts, the course should focus on the reading micro-skills, which were not found in the present teaching and learning process. In general, there are three groups of activities in the class: (a) pre-activities (warning-up, motivating students, reviewing previous lessons), (b) whilst-activities

(lecturing, explaining, students’ doing exercises), and (c) post-activities (reviewing main

points, giving assignments). The instructors tend to cover all the materials in the course

book, which could, to some extent, sacrifice the students’ understanding of the lessons.

The course has only achievement assessment which includes the mid-semester test and the semester test. The tests consist of reading comprehension, vocabulary, and structure items, which reflect the course objectives. No course evaluation is conducted to look into the worth and value of different aspects of the course.

With regard to the class arrangement, the classes are relatively big with 30 to 40 students of the same study program; therefore, the classroom setting is usually in theatre seating, where the students would sit in rows. This seating might affect the teaching and learning activities, in which the interaction would be mostly from the instructor to the students. In terms of the instructors, all have English-Education academic qualification although half of them who had only sarjana’s degrees could be considered under-qualified in accordance with the Law No.14/2005 on teachers and lecturers. The course still employs part-timers. The reluctance of full-time lecturers to teach the English course for

non-English majoring students could be related to the “prestige” of the course, which might

The results of needs analysis give the information on the student profile, the target needs and learning needs. The student profile can be described as follows: The students are mostly at the age of 18 and 19, and three fifth of them are females. The students are from various education study-programs, and have a wide range of English proficiency, from 300 to 450 on the TOEFL, but most of them are in the pre-elementary level (351-400). The

students’ motivation to learn English is average although some of them are highly

motivated. Most students devote enough time to learning English. In the process of

teaching and learning, the students prefer to learn English under the instructor’s guidance

and to work in small groups. During their study at the faculty, the students have an easy access to the library and computer laboratory.

The target needs and learning needs can be described as follows: The students need to develop their reading skill in order to be able to comprehend reading texts, to develop their speaking skill in order to be able to give an oral presentation, and to understand grammatical and vocabulary items in order to support the reading skill. The students want to study English for their future needs to work with computer, communicate in English, and read English textbooks. The students need practice in speaking and reading, grammar and vocabulary, and they prefer to have multiple-choice exercises and discussion. The students also prefer to use printed material and visual aid. In terms of feedback, they prefer to be corrected by the instructor privately after class.

The results of needs analysis become the basis for designing a new English course.

Following the process of Nation & Macalister’s (2010) model of curriculum design, in

goals and objectives, the skills syllabus, the materials, the learning activities, the monitoring and assessment, and the course evaluation.

On the basis of the findings, some conclusions can be drawn:

(1) The present English course is of General English in nature, not ESP. There was no attempt to discover the needs of learners as Hutchinson & Waters (1987) argue that the distinction between ESP and General English lies in the awareness of a need. Besides, one ESP distinct characteristic is that the course should be designed to meet specific needs of learners (Strevens, 1988; Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998).

(2) No needs analysis was conducted prior to designing the present English course. The

students’ needs and the faculty’s expectations were ignored by the language institute

which is in charge of providing the students with the language course.

(3) The prospective English course is an EAP course, more specifically EGAP (English for General Academic Purposes) (Widdowson, 1983; Blue, 1988; Jordan, 1997), because the course has a skills syllabus, which stresses on developing the reading micro-skills of the students in the context of education. This course is quite different from other ESP courses which tend to select topical syllabi and aim at developing all the four language skills.

5.2 Suggestions

On the basis of the conclusions, some suggestions can be put forward:

(1) Needs analysis is an important part in the process of designing a language course. The

university’s language institute which is in charge of designing and running the

designing a language course. The aim is to design a quality course which will meet the needs of learners and the faculty. Considering the cost and time constraints, it may not be possible to conduct the needs analysis every semester or every year, but at a certain period of time, say, in two or three years’ time.

(2) Regarding the main limitation of the study concerning the practical application of the proposed course design, it is suggested that the language institute could adopt the course design, developing the instructional materials, and put it into practice. Only after it has been implemented that the effectiveness and acceptability of the course could be evident.

(3) The findings of this research are specific to the site where the research was conducted. As every faculty has its own characteristics, a similar research conducted at different faculties will result in different findings. The language institute is, therefore, suggested not to use the proposed course design for the students of other faculties. It would be better to design different language courses for the different faculties on the basis of a different needs analysis. Similarly, this proposed course design may not be appropriate for the students of other institutions or universities.

(4) Closely related to needs analysis is the collaboration of all the stakeholders of the language course. Needs analysis will be effective only if all the stakeholders eagerly participate in the process. In the context of this research, the faculty including the departments and the study programs tended to take what the language institute has provided for granted. The faculty, the departments and the study programs should, to some degree, actively contribute to the course by, for example, voicing their needs and

REFERENCES

Abbot, G. (1978). “Motivation, materials, manpower and methods: Some fundamental problems in ESP”. In British Council, English Teaching Information Centre (1978), Individualization in Language Learning, ELT Documents 103, British Council.

Abbot, G. (1981). “Encouraging communication in English: A paradox”. ELT Journal, 35 (3), 228-230.

Alderson, J.C. (1979). “Materials evaluation”. In D.P.L. Harper (Ed.), English for Specific Purposes, papers from the 2nd Latin American Regional Conference, Cocoyoc, Mexico, March 25th-30th, 1979 (pp. 145-155). Mexico: The British Council.

Alderson, J.C. (1988). “Testing and its administration in ESP”. In D. Chamberlain and R.J. Baumgardner (Eds.), ESP in the Classroom: Practice and Evaluation, ELT Document 128 (pp. 87-97). London: Modern English Publications in association with the British Council.

Alderson, J.C., and Waters, A. (1983). “A course in testing and evaluation for ESP

teachers or „How bad were my tests?‟”. In A. Waters (Ed.), Issues in ESP, Lancaster Practical Papers in English Language Education 5, 1982 (pp. 39-61). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Allison, D., and Webber, L. (1984). “What place for performative tests?”. ELT Journal, 38 (3), 199-203.

Alwasilah, A. C. (2004). Perspektif Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris di Indonesia dalam Konteks Persaingan Global. Bandung: CV Andira.

Alwasilah, A.C. (2006). Pokoknya Kualitatif: Dasar-dasar Merancang dan Melakukan Penelitian Kualitatif. Jakarta: Pustaka Jaya.

Alwasilah, A.C. (2007). Language, Culture, and Education: A Portrait of Contemporary Indonesia. Third Edition. Bandung: CV Andira.

Alwi, H. dan Sugono, D. (Eds.). (2000). Politik Bahasa: Risalah Seminar Politik Bahasa. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional.

Aston, G. (1997). “Involving learners in developing learning methods: Exploiting text corpora in self access”. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and Independence in Language Learning (pp. 204–214). London: Longman.

Azar, B.S. (1996). Fundamentals of English Grammar. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Regents.

Basturkmen, H. (2010). Developing Courses in English for Specific Purposes. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Berwick, R. (1989). “Needs assessment in language programming: From theory to practice”. In R.K. Johnson (Ed.), The Second Language Curriculum (pp. 48-62). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biria, R., and Tahririan, M. H. (1994). “The methodology factor in teaching ESP”. English for Specific Purposes, 13, 93–101.

Block, D. (1998). “Tale of a language learner.” Language Teaching Research, 2 (2), 148-176.

Bloor, M., and St John, M.J. (1988). “Project writing: The marriage of process and product”. In P.C. Robinson (Ed.), Academic Writing: Process and Product, ELT Document 129 (pp. 85-94). London: Modern English Publications in association with the British Council.

Blue, G.M. (1988). “Individualising academic writing tuition”. In P.C. Robinson (Ed.), Academic Writing: Process and Product, ELT Documents 129 (pp. 95-99). London: Modern English Publications.

Blue, G.M. (1993). “Nothing succeeds like linguistic competence: The role of language in academic success”. In G.M. Blue (Ed.), Language, Learning and Success: Studying through English, Developments in ELT. Hemel Hempstead: Phoenix ELT.

Bogdan, R.C., and Biklen, S.K. (1998). Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Brammer, M., and Sawyer-Lauçanno, C. (1990). “Business and industry: Specific purpose language training”. In D. Crookall and R.I. Oxford (Eds.), Simulation, Gaming and Language Learning, Chapter 12 (pp. 143-150). New York: Newbury House.

Brannen, J. (Ed.). (1992). Mixing Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Research. Aldershot: Avebury.

Breen, M.P. (1985). “Authenticity in the language classroom”. Applied Linguistics, 6 (1). Brindley, G. (1989). “The role of needs analysis in adult ESL programme design”. In R.K.

British Council (1977). English for Specific Purposes: An international seminar. Proceedings of a seminar held at Bogota, Columbia on April 17th-22nd, 1977, British Council.

British Council. (1978). ESP Course Design. Report on the Dunford House Seminar in 1978, British Council/ELCD.

Britten, D., and O‟Dwyer, J. (1995). “Self-evaluation in in-service teacher training.” In P. Rea-Dickins and A. Lwaitama (Eds.), Evaluation for Development in English Language Teaching (pp. 87-106). London: Macmillan.

Brown, H. D. (1994). Teaching by Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Brown, J.D. (1995). Elements of language curriculum: A systematic approach to program development. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Brown, J.D. (2001). Using Surveys in Language Programs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brumfit, C.J. (1984). “Key issues in curriculum and syllabus design in ELT”. In Curriculum and Syllabus Design in ELT, Dunford House Seminar Report (pp. 7-12). London: the British Council.

Candlin, C.N. (1987). ”Towards task-based language learning”. In C.N. Candlin and D.F. Murphy (Eds.), Language Learning Task, Lancaster Practical Papers in English Language Education, vol. 7 (pp. 5-22). Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall.

Carver, D. (1983). “Some propositions about ESP”. The ESP Journal, 2, 131-137.

Chamber, F. 1980. “A re-evaluation of needs analysis”. ESP Journal, 1(1), 25-33.

Chan, V. (1999). “Developing student autonomy in learning at tertiary level”. Guidelines, 21: 1–18.

Chan, V. (2001). ”Determining students‟ language needs in a tertiary setting”. English Teaching Forum, 39 (3), 16-27.

Charles, D. (1984). ”The use of case studies in Business English”. In G. James (Ed.), The ESP Classroom: Methodology, Materials, Expectations, papers from the 4th Biennial Selmous Conference, Exeter, March 1983. Exeter Linguistic Studies 7 (pp. 24-33). Exeter: University of Exeter.

Christison, M.A., and Krahnke, K. (1986). “Student perceptions of academic language study”. TESOL Quarterly, 20 (1), 61-81.

Clark, E.T. (1997). Designing and implementing an integrated curriculum. Brandon: Holistic Education Press.

Clarke, D.F. (1989). “Communicative theory and its influence on materials production”. Language Teaching, 22 (2).

Coffey, B. (1984). ”ESP─English for Specific Purposes”. Language Teaching, 17 (1), 10-16. workplace courses at a leading Japanese company”. English for Specific Purposes, 26 (4), 426-442.

Crawford, J. (2004). “The role of materials in the language classroom: Finding the balance”. In J.C. Richards and W.A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in Language Teaching: An Anthology of Current Practice (pp. 80-91). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J.W. (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.