Taking Training to

Task: Sex of the

Immediate

Supervisor and Men’s

and Women’s Time

in Initial On-the-Job

Training

Karin Hallde´n

1Abstract

This study examines the effect of the sex of the immediate supervisor on the length of time men and women spend in initial on-the-job training (OJT). Using the 2000 Swedish Level of Living Survey and matched employer regis-try data, this study indicates that men have greater chances of receiving long initial OJT compared with women. In addition, for women employed in the private sector, the chances of receiving long initial OJT are higher if the immediate supervisor is male. For women with a public sector job or for men irrespective of sector, time in initial OJT is independent of the sex of the immediate supervisor.

Keywords

training, gender, supervision, skill

Work and Occupations 2015, Vol. 42(1) 73–102 !The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0730888414555583 wox.sagepub.com

1The Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI), Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Corresponding Author:

Karin Hallde´n, The Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI), Stockholm University, Stockholm, SE10691, Sweden.

In recent years, women have caught up with and even exceeded men in terms of educational attainment in industrialized countries (Buchmann & DiPrete, 2006). Nevertheless, women are still disadvantaged com-pared with men in regard to labor market rewards such as wages and labor market positions of authority (Arulampalam, Booth, & Bryan, 2007; Hallde´n, 2011; Yaish & Stier, 2009). Differentials in workplace training, also called on-the-job training (OJT), across occupations and industries as well as between men and women in the same occupation has been suggested to partially account for gender differences in labor market outcomes (Duncan & Hoffman, 1979; Evertsson, 2004; Gronau, 1988; Mincer & Polachek, 1974; Olsen & Sexton, 1996; Tam, 1997; Tomaskovic-Devey & Skaggs, 2002). To further advance the equality between men and women in the labor market, it is of central importance to increase the understanding of mechanisms reproducing labor market gender inequality. Hence, additional knowledge of the determinants of OJT is therefore essential.

Gender Differences in On-the-Job Training

OJT has been central to the debate over lifelong learning (cf., The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 1991, 2003, 2004), and it is frequently asserted that OJT is crucial for countries’ economic growth and competition in the international market. Another reason for interest in OJT stems from the potential for education in the workplace to provide a leveling effect that would enable employees with little formal education to catch up to more edu-cated workers. However, OJT could also strengthen the effects of formal education if highly educated employees receive more OJT. Hence, OJT is important both from societal and individual perspectives.

It is common to distinguish between formal OJT, informal OJT, and learning-by-doing (cf., Loewenstein & Spletzer, 1999). Formal OJT usu-ally involves a course arranged by the employer that is characterized by structured content and the presence of an instructor, whereas informal OJT implies that the employee is trained by a colleague or supervisor. Learning-by-doing is assumed to consist largely of self-learning in one’s daily work. Initial OJT is considered to be a mix of informal and formal training (with an emphasis on the former) and it also includes compo-nents of learning-by-doing. The duration of initial workplace training (i.e., the training time required at the beginning of a new job to be able to perform the job well) is the prime focus of this study. One reason for focusing attention on time in initial workplace training is that initial OJT has been shown to be more important to current wages than either formal or informal OJT (Korpi & Ta˚hlin, 2009).1In addition, findings from a recent Swedish study revealed a considerable gender gap in such training to women’s disadvantage, even after adjusting for factors such as human capital investments, overeducation in relation to the skill requirements of the job, the proportion women in the occupation, work interruptions, and household work (Gro¨nlund, 2012). Hence, it could be assumed that initial OJT is of great significance to the gap in wages between men and women (cf., Barron, Black, & Loewenstein, 1993; Duncan & Hoffman, 1979; Lynch, 1992). Consequently, it is important to identify the factors that affect time spent in initial work-place training.2

reduced pay during the training time and any training fees. The employer, in turn, is assumed to invest in OJT for an employee if the expected gain (i.e., increased productivity) will exceed the costs (i.e., lost work during the training period and any costs for courses, etc.). In human capital theory, a distinction is made between general and firm-specific human capital, wherein firm-firm-specific human capital can only be used by the employer who provides the training.3The costs and returns of specific OJT are shared by the employer and the employee; the employer pays the employee a wage above marginal productivity during the time in training, but a wage below marginal productivity after the training period. Hence, employers’ and employees’ decisions to invest in specific training are based on predicted tenure. Employers are reluctant to invest in general training for employees because the skills are transferable to other firms, and employees therefore pay accordingly for investments in general OJT. However, it has been found that most OJT, including training provided by the employer, is actually transferable to other employers (e.g., Hansson, 2001).4

A number of studies show that men receive longer and more frequent OJT (both initial and formal) than women, even after important factors related to human capital, labor market characteristics, and the presence of children are statistically controlled (Booth, 1991, 1993; Duncan & Hoffman, 1979; Evertsson, 2004; Green, 1991; Knoke & Ishio, 1998; Lynch, 1992).6 Another important factor in determining the amount of workplace training provided is the educational requirements of the job (Gronau, 1988; Korpi & Ta˚hlin, 2009). However, Gro¨nlund (2012) found that a significant gender gap in time spent in initial training remained after controlling for the educational requirements of the job, occupational sex composition, labor market intermittency, and hours of household work (among other factors). To summarize, according to theory and previous research, a net gap in workplace training that dis-advantages women is expected.

Homophily and Homosocial Reproduction

Another potential explanation for a gender difference in OJT relates to homophily or homosocial reproduction. The former concept is used in network research and implies a higher likelihood that individuals similar in certain dimensions (e.g., being of the same sex or having a similar ethnic background) will have a relationship (cf., Smith-Lovin & McPherson, 1993). For instance, “... if two whites who work within

an organization are more likely to become friends than a white and an African American, then the friendship relationship is homophilous” (p. 228).

Correspondingly, the notion of homosocial reproduction indicates that individuals tend to prefer others like themselves (Kanter, 1977; Miller McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). For example, if women are in the minority in firms, especially in higher positions, their opportunities for career advancement from lower hierarchical levels may be limited (Kanter, 1977; Miller McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). This could, among other things, be attributed to lower centrality in (or a lack of) informal networks in the workplace (given that social similarity facilitates access to such workplace networks), or a tendency for managers to promote individuals of the same sex (e.g., Elliot & Smith, 2004; Smith-Lovin & McPherson, 1993).

male managers had lower wages compared with women in establish-ments with more female managers. This conclusion is supported by Cohen and Huffman (2007), who found that the presence of women in high-status managerial positions narrowed the gender wage gap in workplaces in the United States. However, in their study of small U.S. firms, Penner and Toro-Tulla (2010) did not find any differences in the gender wage gap that could be attributed to the sex of the owner (see also, Penner, Toro-Tulla, & Huffman, 2012). In a similar vein, Hultin (1998) examined the impact of the sex of the highest workplace manager on men’s and women’s chances of reaching higher supervisory positions in the Swedish labor market; no significant effects were found (see Cohen, Broschak, & Haveman, 1998, for corresponding findings on the correlation between the proportion women at the highest manager-ial level and women’s chances of promotion in the United States). However, Kurtulus and Tomaskovic-Devey (2012) show that the pro-portion female top managers in U.S. large private sector firms increased the subsequent female representation in midlevel managerial ranks.7

To conclude: In line with theories on homophily and homosocial reproduction and findings from previous research, having a supervisor of the same sex could constitute an advantage regarding workplace training for employees, especially those in disadvantaged categories (in this case, presumably women).

Are Gender Differences More Pronounced in the

Private Sector?

collective bargaining, and the degree of centralized wage setting10(cf., Anderson & Tomaskovic-Devey, 1995; Blau & Kahn, 2003; le Grand, 1994; Rubary, Grimshaw, & Figueiredo, 2005; see also Hultin & Szulkin, 1999, who linked negative effects of the proportion male super-visors on women’s wages with a decentralized wage-setting policy).11

If we assume that (a) establishments in the public sector have poten-tially higher degrees of bureaucratization, centralization, and union coverage, implying larger restraints due to formalities, and (b) organ-izations in the private sector are possibly exposed to more competition and thus are more focused on economic profits than public sector firms (making secure investments in OJT relatively more important), it is plausible that potential gender differences in access to OJT are larger in private sector firms compared with establishments in the public sector.12For the same reasons, it could be argued that the immediate supervisor’s control over the distribution of initial OJT is greater in the private sector.

Aim of the Study

The aim of this study is to explore the potential effects of sex of the imme-diate supervisor on the length of time men and women spend in initial OJT. According to human capital theory, employers wish to securely invest in OJT, and they may believe that investments in OJT for women are less safe than for men because women tend to bear the primary respon-sibility for children and the household. This can be ascribed to the use of statistical information about women as a category (i.e., statistical discrim-ination; Phelps, 1972). If statistical discrimination were applied, women would be disadvantaged in the distribution of OJT by both male and female supervisors. In line with theories of homophily and homosocial reproduction, one might argue that supervisors may be more inclined to invest in OJT for individuals with characteristics similar to their own. Consequently, male supervisors may be less inclined to invest in OJT for female employees, whereas these gendered disadvantages might not be evident for employees with female supervisors (men may also be dis-advantaged in the latter scenario). This difference is expected to be espe-cially pronounced for employees working in the private sector.13

participate in OJT more often than men if such training took place outside of regular working hours because of women’s higher likelihood of having family responsibilities. However, because initial workplace training can be assumed to take place during regular working hours, a gender difference in the choice to participate in initial OJT is not likely to be a concern. Second, it is presumed that the immediate supervisor has influence over the subordinates’ time in initial OJT. Naturally, this influence is likely to vary depending on the size of the establishment, industry and sector, among other things. Also, it is plausible that the number of subordinates assigned to a supervisor could affect the distri-bution of time in initial OJT. These factors are taken into account, to at least some extent, by adjusting for them in the analyses.

The Swedish Context

Sweden is generally depicted as one of the most gender egalitarian coun-tries in the world alongside with the other Nordic councoun-tries (World Economic Forum, 2010). Sweden has policies that facilitate a combin-ation of work and family (e.g., publicly provided childcare)14 and the female labor force participation is high—approximately 70% in 2000 (Eurostat, 2002). However, part-time work is common (Eurostat, 2002), especially among women with young children. Although the share of employed women working part time is more than 36% (Eurostat, 2002), a large fraction works long part-time hours (i.e., 30 hours or more per week; Hallde´n, Gallie, & Zhou, 2012). Although Swedish women’s labor market activity is among the highest in Europe, the proportion of female managers was only 30.3% in 2001, which was just slightly above the European Union (EU) average (European Commission, 2009; see also Yaish & Stier, 2009). Also, the labor market sex segregation is not par-ticularly low, and in 2001, the difference in the distribution of women and men across occupations and sectors was higher in Sweden compared with the EU average (European Commission, 2009; Yaish & Stier, 2009). This feature is sometimes linked to the high female labor force participation and the large public sector (Nermo, 1999).15

Data, Variables, and Method

LNU and LOUISE

matched firm registry data from the Longitudinal Database About Education, Income and Employment (En longitudinell databas kring utbildning, inkomst och sysselsa¨ttning, LOUISE), provided by Statistics Sweden.16The 2000 LNU consists of a nationally representative sample of individuals aged 18 to 75 years with information collected through face-to-face interviews. The response rate was 76.6%, providing an effective sample consisting of 5,142 individuals (for more information on this survey, see Ga¨hler, 2004). The subsample analyzed includes 1,600 employees aged between 20 to 65 years who worked in establish-ments with 10 or more employees.

Dependent Variable and Method

Initial OJT was originally a categorical variable based on the following question: “Apart from the competence necessary to get a job such as yours, how long does it take to learn to do the job reasonably well?” Response options were as follows:1 day or less,2–5 days,1–4 weeks,1–3 months,3 months–1 year,1–2 years, andMore than 2 years. This meas-ure has frequently been used in both early and more recent training literature (e.g., Barron, Black, & Loewenstein, 1993; Duncan & Hoffman, 1979; Gro¨nlund, 2012; Korpi & Ta˚hlin, 2009; Loewenstein & Spletzer, 1999). The variable was transformed into days of training (up to 792 days), and its logarithm was used in the analyses (cf., Korpi & Ta˚hlin, 2009). Analyses were conducted using ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions.17

Independent Variables and Controls

Sex of the immediate supervisor was determined through the question: “Is your immediate supervisor/boss a man or a woman?”18A limitation of this question is that we cannot be certain that the current supervisor was also the supervisor when the initial training took place. Hence, sensitivity analyses were conducted for the final models in Table 5, using only employees with very short tenure (2 years or less). The results supported the findings presented below.

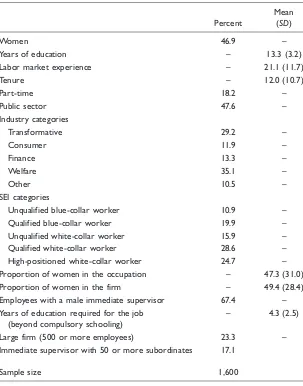

supervisor in the private sector.Number of subordinates of the immediate supervisor(given a value of 1 if the immediate supervisor had more than 50 subordinates) could potentially mediate possible effects of sex of the immediate supervisor on gender differences in the duration of initial OJT why this factor was also controlled for in the analyses. Both Swedish and international studies show that skilled workers and employees with exten-sive formal education receive more OJT relative to others (e.g., Bassanini et al., 2005; Bjo¨rklund & Regne´r, 1996; Booth, 1991; Evertsson, 2004; Jacobs et al., 1996; O’Connell & Byrne, 2012; OECD, 2003). One reason for this finding might be that the employer wants to invest securely, and an individual with extensive formal education signals the potential to assimilate the training provided. In addition, highly skilled jobs might require more training than less qualified work. Hence, the variablesyears of education,skill requirements of the job,19 andsocioeconomic position were statistically controlled in the analyses. In addition, the analyses also controlled forworking life experienceand its square term (to take into account potential curve linear effects),tenure,20and (self-defined) part-time work.21Proportion women in the occupation22andproportion women in the firm23were also statistically controlled in the analyses because trad-itionally female occupations tend to involve shorter periods of training (cf., Tam, 1997; Tomaskovic-Devey & Skaggs, 2002), and female super-visors are presumably more common in occupations and firms with a high proportion of women.24 Employees in large firms are likely to receive more OJT (e.g., Bassanini et al., 2005; Frazis et al., 2000; Lynch & Black, 1998; O’Connell & Byrne, 2012), and the discretion of the super-visor may also differ between large and small establishments. Furthermore, time in initial workplace training could be assumed to vary across branches of industry. Hence,large firm(a dichotomous meas-ure given a value of 1 if the respondent worked in a workplace with 500 or more employees), and industry25 were included in the analyses. Descriptive statistics for these variables are presented in Table 1. In this table, we see that nearly 70% of the sample has a male immediate super-visor and approximately half of the respondents work in the public sector.

Results

Contrary to what has been reported in other studies, the present findings reveal that long initial workplace training is slightly more common in the private sector than the public sector. One reason for

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for the Variables Used in the Analyses.

Percent

Mean (SD)

Women 46.9 –

Years of education – 13.3 (3.2)

Labor market experience – 21.1 (11.7)

Tenure – 12.0 (10.7)

Part-time 18.2 –

Public sector 47.6 –

Industry categories

Transformative 29.2 –

Consumer 11.9 –

Finance 13.3 –

Welfare 35.1 –

Other 10.5 –

SEI categories

Unqualified blue-collar worker 10.9 –

Qualified blue-collar worker 19.9 –

Unqualified white-collar worker 15.9 –

Qualified white-collar worker 28.6 –

High-positioned white-collar worker 24.7 –

Proportion of women in the occupation – 47.3 (31.0)

Proportion of women in the firm – 49.4 (28.4)

Employees with a male immediate supervisor 67.4 –

Years of education required for the job (beyond compulsory schooling)

– 4.3 (2.5)

Large firm (500 or more employees) 23.3 –

Immediate supervisor with 50 or more subordinates 17.1

Sample size 1,600

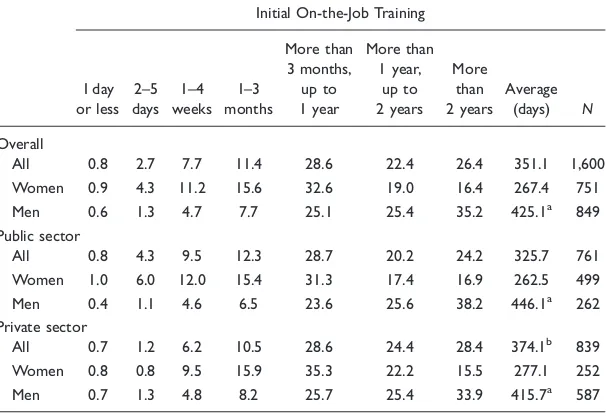

these conflicting results might be differences in the operationalization of OJT. Women in the public sector received the shortest amount of time in initial OJT, and because public sector male employees received the longest amount of initial OJT, the gender gap in initial training was largest in the public sector.

The potential influence of sex of the immediate supervisor on the gender gap in initial OJT is then analyzed using multivariate regression techniques (see Table 3).

Model 1 (Table 3) indicates that women’s considerably shorter time in initial OJT persists when a full set of control variables are introduced. Labor market experience and having a high socioeconomic position increase time spent in initial OJT. The educational requirements of the job are a stronger predictor of OJT than years of education (cf., Korpi & Ta˚hlin, 2009). As seen in Model 1 (Table 3), the latter is not

Table 2. The Duration of Initial On-the-Job Training by Sex and Sector (percentages). Women 0.9 4.3 11.2 15.6 32.6 19.0 16.4 267.4 751 Men 0.6 1.3 4.7 7.7 25.1 25.4 35.2 425.1a 849

Public sector

All 0.8 4.3 9.5 12.3 28.7 20.2 24.2 325.7 761

Women 1.0 6.0 12.0 15.4 31.3 17.4 16.9 262.5 499 Men 0.4 1.1 4.6 6.5 23.6 25.6 38.2 446.1a 262 Private sector

All 0.7 1.2 6.2 10.5 28.6 24.4 28.4 374.1b 839 Women 0.8 0.8 9.5 15.9 35.3 22.2 15.5 277.1 252 Men 0.7 1.3 4.8 8.2 25.7 25.4 33.9 415.7a 587

Note.Source material is the 2000 Swedish Level of Living Survey (LNU). Employees aged 20 to 65 years in firms with 10 or more employees.

aThe average time in initial OJT for male employees is significantly different from the average

time in initial OJT for female employees at the 0.1% level.bThe average time in initial OJT for

Table 3. The Duration of Initial On-the-Job Training (Estimates From OLS Regressions With SEs).

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

b SE b SE b SE

Woman 0.55*** 0.08 0.39*** 0.08 – –

Years of education 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 Labor market experience 0.06*** 0.01 0.06*** 0.01 0.06*** 0.01 Labor market experience squared 0.00** 0.00 0.00*** 0.00 0.00*** 0.00

Tenure 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

Public sector 0.08 0.10 0.06 0.10 0.06 0.10

Industry

Transformative sector (ref.)

Consumer industry 0.18 0.11 0.14 0.11 0.14 0.11 Finance industry 0.32** 0.11 0.28* 0.11 0.28* 0.11 Welfare sector 0.44*** 0.12 0.18 0.14 0.18 0.14 Other industries 0.05 0.14 0.02 0.14 0.01 0.14 Socioeconomic position

Unqualified blue-collar worker (ref.)

Qualified blue-collar worker 0.97*** 0.12 0.97*** 0.12 0.98*** 0.12 Unqualified white-collar worker 1.13*** 0.13 1.25*** 0.13 1.24*** 0.13 Qualified white-collar worker 1.44*** 0.12 1.48*** 0.12 1.47*** 0.12 High-positioned white-collar worker 1.62*** 0.14 1.61*** 0.14 1.61*** 0.14 Large firm (500 or more employees) 0.04 0.07 0.04 0.07 0.04 0.07 Educational requirements of the job 0.07*** 0.02 0.06*** 0.02 0.06*** 0.02

Part-time 0.11 0.09 0.03 0.09 0.03 0.09

% women in occupation 0.01*** 0.00 0.01*** 0.00

% women in firm 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

Immediate supervisor male 0.21* 0.09 – –

Immediate supervisor with 50 subordinates

0.10 0.08 0.10 0.08

WomanFemale Supervisor (ref.)

WomanMale Supervisor 0.26* 0.10

ManFemale Supervisor 0.50** 0.15

ManMale Supervisor 0.61*** 0.11

Constant 3.30*** 3.25*** 2.85***

R2 0.29 0.30 0.30

Number of cases 1,600 1,600 1,600

Note.Source material is the 2000 Swedish Level of Living Survey (LNU) and matched registry data. Employees aged 20 to 65 years in firms with 10 or more employees.

significant when the two variables are jointly included in the model. The duration of workplace training is shorter in the finance and welfare industries than the transformative industry, but the negative correlation between the welfare industry and OJT diminishes once the proportion women in the occupation is included (Model 2). Furthermore, Model 2 (Table 3) shows that having a high proportion of women in a given occupation reduces the chances of long initial OJT (cf., Gro¨nlund, 2012), although the effect is very small.26

In addition, sex of the immediate supervisor was introduced in Model 2 (Table 3). Having a male supervisor increases the duration of initial OJT. To determine whether a potential difference between the time men and women spend in initial OJT is influenced by sex of the immediate supervisor, four dummy variables were created: women with female supervisors (the reference category), women with male supervisors, men with female supervisors, and men with male visors. As Model 3 (Table 3) indicates, women working for male super-visors received longer initial workplace training compared with women working for female supervisors. For men, on the other hand, the length of the initial training did not differ significantly by the supervisor (esti-mates not shown).

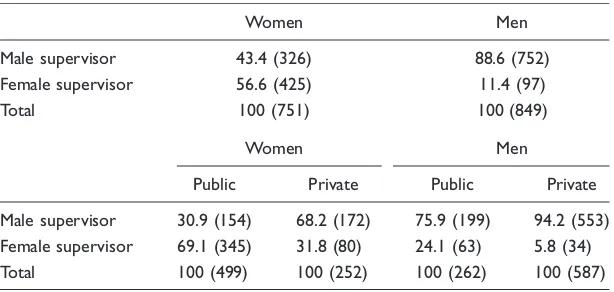

The analyses continued by examining the public and private sectors separately, as it was expected that potential effects of sex of the

Table 4. The Distribution of Men and Women by Sex of the Immediate Supervisor and Sector (Percentage With Number in Parentheses).

Women Men

Male supervisor 43.4 (326) 88.6 (752)

Female supervisor 56.6 (425) 11.4 (97)

Total 100 (751) 100 (849)

Women Men

Public Private Public Private

Male supervisor 30.9 (154) 68.2 (172) 75.9 (199) 94.2 (553) Female supervisor 69.1 (345) 31.8 (80) 24.1 (63) 5.8 (34)

Total 100 (499) 100 (252) 100 (262) 100 (587)

immediate supervisor on differences in the duration of men’s and women’s initial training would be larger in the private sector due to increased exposure to competition and less formalized organizational structures. The distribution of men and women by sex of the immediate supervisor and sector is presented in Table 4. Especially in the pri-vate sector, men were far more likely to work for other men than for women, with only 5.8% of men in the private sector and 24.1% in the public sector with female immediate supervisors. More than 50% of women worked for female supervisors, although this figure dropped to approximately one third when looking only at the private sector, whereas 69.1% of all women in the public sector had a female immedi-ate supervisor.

In Table 5, the proportion of women in the occupation and the firm, the educational requirements of the job, and the socioeconomic position were added stepwise to the analyses, as these factors were expected to be of specific importance to the association between sex of the immediate supervisor and the differences in the duration of initial training for men and women in the public and private sectors. Starting with the public sector (see Model 1a, Table 5), we observe that men (with both male and female immediate supervisors) received longer initial OJT compared with women working for women. However, the significant positive asso-ciation for men with female supervisors diminished once educational requirements of the job and socioeconomic position were controlled for, whereas the longer duration of initial OJT for men with male super-visors remained (see Model 3a, Table 5). In addition, there was no sig-nificant difference in the duration of the initial training between public sector male employees with male supervisors and male employees with female supervisors (estimates not shown). It is evident from Models 1a to 3a (Table 5) that working for a male supervisor does not increase the likelihood of long initial OJT for women in the public sector.

Table 5. The Duration of Initial On-the-Job Training by Sector (Estimates From OLS Regressions WithSEs).

Without controls for the proportion of women in the occupation, the proportion

of women in the firm, educational requirements,

and SEI category

Adding controls for the proportion of women in the occupation and the

proportion of women in the firm

Adding controls for educational requirements

of the job and SEI category

Model 1b Model 2b Model 3b

Private sector b SE b SE b SE

WomanFemale Supervisor (ref.)

WomanMale Supervisor 0.25 0.14 0.18 0.14 0.03 0.14

ManFemale Supervisor 0.54** 0.20 0.44* 0.20 0.33 0.19

ManMale Supervisor 0.68*** 0.15 0.50** 0.17 0.44** 0.16

Constant 2.60*** 2.99*** 3.29***

R2 0.21 0.23 0.32

Number of cases 761 761 761

(continued)

by guest on October 1, 2016

wox.sagepub.com

Without controls for the proportion of women in the occupation, the proportion

of women in the firm, educational requirements,

and SEI category

Adding controls for the proportion of women in the occupation and the

proportion of women in the firm

Adding controls for educational requirements

of the job and SEI category

Model 1b Model 2b Model 3b

Private sector b SE b SE b SE

WomanFemale Supervisor (ref.)

WomanMale Supervisor 0.88***a 0.17 0.84***b 0.18 0.72***a 0.17

ManFemale Supervisor 1.16*** 0.26 1.10*** 0.26 0.98*** 0.24

ManMale Supervisor 1.16*** 0.16 1.06*** 0.19 1.03*** 0.18

Constant 2.27*** 2.41*** 2.05***

R2 0.16 0.17 0.30

Number of cases 839 839 839

Note.The analyses are adjusted for education, labor market experience, and its square term, tenure, industry, firm size, part-time work, and whether the supervisor had 50 or more subordinates. SEI¼Swedish socioeconomic classification. Source material is the 2000 Swedish Level of Living Survey (LNU) and matched registry data. Employees aged 20 to 65 years in firms with 10 or more employees.

aThe estimate for private sector employees is significantly different from the corresponding estimate for the public sector at the 1% level.bThe estimate

for private sector employees is significantly different from the corresponding estimate for the public sector at the 5% level. *p5.05. **p5.01. ***p5.001.

89

by guest on October 1, 2016

wox.sagepub.com

To take into account a potential bias in the measurement of sex of the immediate supervisor at the time of the initial workplace training, the final analyses presented in Table 5 (Model 3a and Model 3b) were also conducted for employees with very short tenure (2 years or shorter). The findings of these analyses supported the results presented earlier (esti-mates not shown).27

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the potential impact of sex of the immediate supervisor on the length of time men and women spend in initial OJT in the Swedish labor market. Hypotheses were formulated based on theories of homophily, homosocial reproduction, and human capital, as well as previous research. The analyses were based on data from the 2000 Swedish Level of Living Survey and matched employer registry data.

explain why women with male supervisors in the private sector report longer initial OJT than those with female supervisors.

The measure used in this study, initial workplace training, covers only parts of what is commonly argued to constitute OJT. Another form of OJT is continuous training on the job, which can be formal or informal in nature. In exploratory analyses on formal and informal OJT, the result that private sector female employees with male imme-diate supervisors spend more time in training compared with their equivalents with female supervisors was found only for informal OJT for individuals in high-skill jobs (i.e., positions requiring 3 years or more of education beyond compulsory schooling) and not at all for formal OJT (not shown).28Hence, caution should be used when making infer-ences about other types of OJT.

Conclusion

for the private sector seems sensible if we assume that the public sector has a more bureaucratic organization, implying that the promotion and recruitment processes to managerial positions are formalized to a greater extent.32 This could be assumed to work to the advantage of women, not only implying greater proportion female managers (cf., Reskin & Branch McBrier, 2000) but also presumably leading to more women working at advanced managerial levels and being in charge of more qualified positions.

Nonetheless, this interpretation can be questioned, considering that the duration of the initial workplace training for men is independent of the immediate supervisor’s sex also in the private sector (and as the findings for informal OJT were only valid for high-skilled jobs). However, the number of private sector male employees supervised by women is low, and these female managers may constitute a compara-tively selected category given that they may be supervising relacompara-tively high-skilled positions. Hence, even if the analyses statistically control for the educational requirements of the position, we cannot eliminate the possibility of there being additional aspects of the complexity of the job that are not grasped by this measure, which could partially account for the results (see e.g., Ku, 2011, exemplifying sex segregation within the same occupation by studying gendered choice of specialty among physicians). Also, the relatively small sample size and the lack of lon-gitudinal (or retrospective) information about the immediate super-visor’s sex at the time when the initial OJT took place constitute limitations of the analyses.

Acknowledgements

I thank the participants in the seminar series on Social Stratification, Welfare and Social Policy at the Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI), especially Tomas Korpi and Ryszard Szulkin, for their valuable comments on this work. In addition, this study benefited from the suggestions of Sunnee Billingsley, David Grusky, Juho Ha¨rko¨nen, Magnus Nermo, Reinhard Pollak, Michael Ta˚hlin, and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, as well as from comments made by the anonymous reviewers. I also thank Charlotta Magnusson for providing data on the proportion women in the occupation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was sup-ported by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS 2004-1908; 2007-2127).

Notes

1. It is, however, noted by the authors that initial, formal, and informal OJT partially overlap (Korpi & Ta˚hlin, 2009).

2. Another reason for operationalizing OJT as initial workplace training is that this measure was used by Gro¨nlund (2012) and Korpi and Ta˚hlin (2009) when studying the determinants, distribution, and effects of workplace train-ing in Sweden.

3. Becker (1964/1993) notes, however, that “Much on-the-job training is neither completely specific nor completely general but increases productivity more in the firms providing it and falls within the definition of specific training” (p. 40).

4. See Acemoglu and Pischke (1999) for a discussion of the prerequisites for training in an imperfect labor market.

5. Also, Becker (1985) argues that “...housework is more effort intensive than leisure and other household activities...” (p. 55). Hence, women’s greater responsibility for children and the household would according to this argu-ment imply that they spend less effort in labor market work compared with men working the same number of hours (Becker, 1985).

7. In addition, some studies have explored the effects of the sex of the business owner and the sex composition of the management and the firm on within-firm gender integration (e.g., Bygren & Kumlin, 2005; Carrington & Troske, 1995; Huffman, Cohen, & Pearlman, 2010). In addition, Stainback and Kwon (2012) used Korea data and showed that high shares of female man-agers lowered firm sex segregation, while high shares of women in super-visory positions had the opposite effect. Also, Maume (2011) examined whether self-rated advancement opportunities were influenced by the sex of the supervisor (among other factors). He found that men with female supervisors rated their chances to advancement higher compared with men working for men. There were no significant effects for female employees. 8. Contrary to the other studies referenced, the figures from Bjo¨rklund and

Regne´r (1996) and SCB (2002) are not standardized.

9. However, in the study by Murphy et al. (2008), the public sector training advantage vanished when the sorting of employees was taken into account. 10. Sa¨ve-So¨derberg (2003) used Swedish data and showed that individual wage bargaining increased the gender wage gap because women, among other things, submit lower wage bids than men do. For a comparison of the wage setting systems in Europe and United States, see, for example, Ebbinghaus and Kittel (2005).

11. Also, Kurtulus and Tomaskovic-Devey (2012) showed that the positive effect of the proportion female top managers on the subsequent female representation in the midlevel managerial ranks in U.S. large private sector firms was more persistent in firms holding federal contracts. 12. See however Byron (2010), showing that verified cases of race and gender

discrimination varied little by sector in the United States but that the types of discrimination differed. The rate of firing discrimination was higher in the private sector while the rate of promotion discrimination was larger in the public sector.

14. Nonetheless, this does not imply that Swedish men and women do not experience work–family conflict (see e.g., Ruppanner & Huffman, 2014). 15. Sweden and the other Nordic countries have high average incidences of

workplace training compared with other European countries and the United States (Bassanini et al., 2005). For an overview of workplace train-ing in Europe, see Bassanini et al. (2005).

16. For more information about this database, see SCB (2005).

17. The analyses were also replicated using the original measure and ordered logistic regressions, which, by and large, provided similar results. Likewise, conducting the analyses with the standard errors clustered around occupa-tion gave comparable results. Because the number of individuals working in the same firm was low (1,419 different establishments were reported for the 1,600 respondents included in the selected LNU sample), there was little need to correct for potential nesting of respondents within firms.

18. Ten individuals reported having two managers (one man and one woman). These respondents were excluded.

19. This variable was measured with the questions: “Is any schooling or voca-tional training above elementary schooling necessary for your job?” and, if yes, “About how many years of education above elementary school are necessary?”

20. Tenure is included in the analyses to correct for potential recall bias (as employees with long tenure might recall their time in initial training less precisely than individuals with shorter tenure).

21. Including the variablesmarried or cohabitingandnumber of children in the householdin the analyses only affected the other estimates in a very minor way, and neither of the two variables reached significance.

22. Based on a detailed three-digit occupational classification (90 occupational categories are represented in the selected LNU sample).

23. This information is obtained through employer registry data.

24. In addition, the extent to which career opportunities might be gendered could presumably also differ with the share of women in the occupation and in the firm (see, e.g., Hultin, 2003).

measure is 0.64, although excluding the public sector from the analyses in Table 3 affected the other estimates only in a very minor way.

26. The negative effect of the proportion women on time in initial OJT is stronger though if dummy variables are used to indicate the sex composition of the occupation.

27. The exceptions were the longer duration of initial OJT for men with male supervisors in the public sector and men with female supervisors in the private sector when compared with women with female supervisors in each sector. Estimates were significant only at the 10% level.

28. The question measuring informal OJT is posed as follows: “To what extent does your work mean that you learn new things?” This variable has five response alternatives ranging fromTo a very large extenttoNot at all, and it measures the incidence rather than the time spent in informal OJT. The estimate was significant at the 5% level and differed at the 1% level from the corresponding estimate for the public sector. There was no significant difference between men with a female supervisor and men with a male supervisor in the public or private sectors. The measurement of formal OJT consists of two questions. First the respondent is asked a yes/no ques-tion on the incidence of formal OJT: “Have you in the last 12 months received any kind of education on paid worktime?” If the respondent answers yes, a question on the length of the training is posed: “How many whole working days altogether was this education?”

29. For more on the types of support a social network in the workplace com-monly provide, see, for example, McGuire (2007).

30. Only 13.6% of respondents employed in the private sector reported having a female supervisor, compared with 53.6% of individuals working in the public sector (cf., Table 4).

31. Analyses on the Swedish Level of Living Survey 2000 (not shown) confirm that female managers are indeed less likely to hold positions of high skill (measured as the skill requirements of the job) compared with male managers.

32. In addition, it should be noted that women constitute a clear majority of all public sector employees.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Pischke, J.-S. (1999). Beyond Becker: Training in imperfect labour markets.The Economic Journal,109, 112–142.

Altonji, J. G., & Spletzer, J. R. (1991). Worker characteristics, job characteris-tics, and the receipt of on-the-job training. Industrial & Labor Relations Review,45, 58–79.

Anderson, C. D., & Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (1995). Patriarchal pressures: An exploration of organizational processes that exacerbate and erode gender earnings inequality.Work and Occupations,22, 328–356.

Arulampalam, W., Booth, A. L., & Bryan, M. L. (2007). Is there a glass ceiling over Europe? Exploring the gender pay gap across the wage distribution. Industrial and Labor Relations Review,60, 163–186.

Baron, J. N., & Bielby, W. T. (1980). Bringing the firms back in: Stratification, segmentation, and the organization of work.American Sociological Review, 45, 737–765.

Barron, J. M., Black, D. A., & Loewenstein, M. A. (1993). Gender differences in training, capital, and wages.Journal of Human Resources,28, 343–346. Bassanini, A., Booth, A., Brunello, G., De Paola, M., & Leuven, E. (2005).

Workplace training in Europe(Chapter 2, IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 1640). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Becker, G. S. (1971 [1957]).The economics of discrimination(2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Becker, G. S. (1985). Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of Labor Economics,3, 33–58.

Becker, G. S. (1991 [1981]).A treatise on the family(Enlarged ed., Chapter 2, pp. 30–79). Cambridge, England: Harvard University Press.

Becker, G. S. (1993 [1964]).Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education(3rd ed., Chapter 3, pp. 29–58). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bjo¨rklund, A., & Regne´r, H. (1996). Humankapital-teorin och utbildning pa˚ arbetsplatserna [The human capital theory and training in the workplace]. In C. le Grand, R. Szulkin, & M. Ta˚hlin (Eds.), Sveriges arbetsplatser— Organisation, personalutveckling, styrning [Establishments in Sweden— Organization, personnel development, control] (Chapter 4, pp. 88–111). Stockholm, Sweden: SNS Fo¨rlag.

Blau, F. D., & Ferber, M. A. (1992 [1986]).The economics of women, men, and work(Chapter 7, 2nd ed., pp. 188–237). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2003). Understanding international differences in

the gender pay gap.Journal of Labor Economics,21, 106–144.

Booth, A. L. (1991). Job-related formal training: Who receives it and what is it worth?Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics,53, 281–294.

Booth, A. L. (1993). Private sector training and graduate earnings.Review of Economics and Statistics,75, 164–170.

Buchmann, C., & DiPrete, T. (2006). The growing female advantage in collage completion: The role of family background and academic achievement. American Sociological Review,71, 515–541.

Bygren, M., & Kumlin, J. (2005). Mechanisms of organizational sex segregation: Organizational characteristics and the sex of newly recruited employees. Work and Occupations,32, 39–65.

Byron, R. A. (2010). Discrimination, complexity, and the public/private sector question.Work and Occupations,37, 435–475.

Charles, M., & Grusky, D. B., (Eds.). (2004).Occupational ghettos. The world-wide segregation of women and men. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Cohen, L. E., Broschak, J. P., & Haveman, H. A. (1998). And then there were more? The effect of organizational sex composition on the hiring and pro-motion of managers.American Sociological Review,63, 711–727.

Cohen, N. P., & Huffman, M. L. (2007). Working for the woman? Female managers and the gender wage gap. American Sociological Review, 72, 681–704.

Dickerson, N., Schur, L., Kruse, D., & Blasi, J. (2010). Worksite segregation and performance-related attitudes.Work and Occupations,37, 45–72. Duncan, G. J., & Hoffman, S. (1979). On-the-job training and earnings

differ-ences by race and sex.The Review of Economics and Statistics,61, 594–603. Ebbinghaus, B., & Kittel, B. (2005). European rigidity versus American flexi-bility? The institutional adaptability of collective bargaining. Work and Occupations,32, 163–195.

Elliot, J. R., & Smith, R. A. (2004). Race, gender and workplace power. American Sociological Review,69, 365–386.

England, P. (2005). Gender inequality in labour markets: The role of mother-hood and segregation.Social Politics,12, 264–288.

Este´vez-Abe, M. (2005). Gender bias in skills and social policies: The varieties of capitalism perspective on sex segregation.Social Politics,12, 180–215. European Commission. (2009).Gender segregation in the labour market. Root

causes, implications and policy responses in the EU. European Commission’s Expert Group on Gender and Employment (EGGE). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurostat. (2002).Eurostat yearbook 2002. The statistical guide to Europe. Data 1990–2000. European Commission. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Evertsson, M. (2004). Formal on-the-job training: A gender-typed experience and wage-related advantage?European Sociological Review,20, 79–94. Frazis, H., Gittleman, M., & Joyce, M. (2000). Correlates of training: An

ana-lysis using both employer and employee characteristics.Industrial and Labor Relations Review,53, 443–462.

Ga¨hler, M. (2004). Levnadsniva˚underso¨kningen [The Swedish level of living survey]. In M. Bygren, M. Ga¨hler, & M. Nermo (Eds.), Familj och arbete—Vardagsliv i fo¨ra¨ndring[Family and work—Everyday life in transition] (Appendix 1, pp. 322–327). Stockholm, Sweden: SNS Fo¨rlag.

Green, F. (1991). Sex discrimination in job-related training.British Journal of Industrial Relations,29, 295–304.

Gronau, R. (1988). Sex-related wage differentials and women’s interrupted labor careers—The chicken or the egg.Journal of Labor Economics,6, 277–301. Gro¨nlund, A. (2012). On-the-job training—A mechanism for segregation?

Hallde´n, K. (2011).What’s sex got to do with it? Women and men in European labour markets(The Swedish Institute for Social Research Dissertation Series No. 85). Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University.

Hallde´n, K., Gallie, D., & Zhou, Y. (2012). The skills and autonomy of female part-time work in Britain and Sweden.Research in Social Stratification and Mobility,30(2), 187–201.

Hansson, B. (2001).Essays on human capital investments(Study 1, pp. 27–54). Stockholm, Sweden: School of Business, Stockholm University.

Huffman, M. L., Cohen, N. P., & Pearlman, J. (2010). Engendering change? Organizational dynamics and workplace gender desegregation, 1975–2005. Administrative Science Quarterly,55, 255–277.

Hultin, M. (1998). Gender differences in workplace authority: Discrimination and the role of organizational leaders.Acta Sociologica,41, 99–113. Hultin, M. (2003). Some take the glass escalator, some hit the glass ceiling?

Career consequences of occupational sex segregation. Work and Occupations,30, 30–61.

Hultin, M., & Szulkin, R. (1999). Wages and unequal access to organizational power: An empirical test of gender discrimination. Administrative Science Quarterly,44, 453–472.

Hultin, M., & Szulkin, R. (2003). Mechanisms of inequality. Unequal access to organizational power and the gender wage gap. European Sociological Review,19, 143–159.

Jacobs, J. A., Lukens, M., & Useem, M. (1996). Organizational, job and indi-vidual determinants of workplace training: Evidence from the National Organizations Survey.Social Science Quarterly,77, 159–176.

Kanter, R. M. (1977).Men and women of the corporation. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Knoke, D., & Ishio, Y. (1998). The gender gap in company job training.Work and Occupations,25, 141–167.

Korpi, T., & Ta˚hlin, M. (2009).A tale of two distinctions: The significance of job requirements and informal workplace training for the training gap. Unpublished manuscript, The Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University. Retrieved from http://www2.sofi.su.se/mta/ Ku, C. M. (2011). When does gender matter? Gender differences in speciality

choice among physicians.Work and Occupations,38, 221–262.

Kurtulus, F., & Tomaskovic-Devey, A. (2012). Do female top managers help women to advance? A panel study using EEO-1 records.The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,639, 173–197.

Loewenstein, M. A., & Spletzer, J. R. (1999). Formal and informal training: Evidence from the NLSY.Research in Labor Economics,18, 403–438. Lynch, L. M. (1992). Private-sector training and the earnings of young workers.

American Economic Review,82, 299–312.

Lynch, L. M., & Black, S. E. (1998). Beyond the incidence of employer-provided training.Industrial and Labor Relations Review,52, 64–81.

Maume, D. J. (2011). Meet the new boss... same as the old boss? Female supervisors and subordinate career prospects.Social Science Research,40, 287–298.

McGuire, G. M. (2007). Intimate work: A typology of the social support that workers provide to their network members. Work and Occupations, 34, 125–147.

Miller McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks.Annual Review of Sociology,27, 415–444. Mincer, J., & Polachek, J. (1974). Family investments in human capital:

Earnings of women.Journal of Political Economy,82, 76–108.

Murphy, P., Latreille, P. L., Jones, M., & Blackaby, D. (2008). Is there a public sector training advantage? Evidence from the workplace employment rela-tions survey.British Journal of Industrial Relations,46, 674–701.

Nermo, M. (1999). Structured by gender. Patterns of sex segregation in the Swedish labour market. Historical and cross-national comparisons (The Swedish Institute for Social Research Dissertation Series No. 41). Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University.

Neumark, D., & McLennan, M. (1995). Sex discrimination and women’s labor market outcomes.Journal of Human Resources,30, 713–740.

O’Connell, P. J., & Byrne, D. (2012). The determinants and effects of training at work: Bringing the workplace back in.European Sociological Review,28(3), 283–300.

O’Halloran, P. L. (2008). Gender differences in formal on-the-job training: Incidence, duration, and intensity.Labour,22, 629–659.

Olsen, R. N., & Sexton, E. A. (1996). Gender differences in the returns to and the acquisition of on-the-job training.Industrial Relations,35, 59–77.

Penner, A. M., & Toro-Tulla, H. J. (2010). Women in power and gender wage inequality: The case of small businesses. In C. L. Williams, & K. Dellinger, (Eds.) Gender and sexuality in the workplace. Research in the sociology of work 20(Vol. 20, pp. 83–105). Bingley, England: Emerald.

Penner, A. M., Toro-Tulla, H. J., & Huffman, M. L. (2012). Do women man-agers ameliorate gender differences in wages? Evidence from a large grocery retailer.Sociological Perspectives,55(2), 365–381.

Phelps, E. S. (1972). The statistical theory of racism and sexism. American Economic Review,62, 659–661.

Reskin, B. F., & Branch McBrier, D. (2000). Why not ascription? Organizations’ employment of male and female managers. American Sociological Review,65, 210–233.

Reskin, B. F., & Ross, C. E. (1992). Jobs, authority, and earnings among man-agers: The continuing significance of sex. Work and Occupations, 19, 342–365.

Ridgeway, C. L. (2006). Gender as an organizing force in social relations: Implications for the future of inequality. In F. D. Blau, M. C. Brinton, & D. B. Grusky (Eds.),The declining significance of gender? (Chapter 9, pp. 265–287).New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Rubary, J., Grimshaw, D. P., & Figueiredo, H. (2005). How to close the gender pay gap in Europe: Towards the gender mainstreaming of pay policy. Industrial Relations Journal,36, 184–213.

Ruppanner, L., & Huffman, M. L. (2014). Blurred boundaries: Gender and work-family interference in cross-national context.Work and Occupations, 41, 210–236.

Sa¨ve-So¨derberg, J. (2003). Essays on gender differences in economic decision-making(The Swedish Institute for Social Research Dissertation Series No. 59). Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University.

Simpson, P. A., & Stroh, L. K. (2002). Revisiting gender variation in training. Feminist Economics,8, 21–53.

Smith-Lovin, L., & McPherson, J. M. (1993). You are who you know: A net-work approach to gender. In P. England (Ed.),Theory on gender, feminism on theory(Chapter 11, pp. 223–251). New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. Stainback, K., & Kwon, S. (2012). Female leaders, organizational power, and

sex segregation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,639, 217–235.

Statistics Sweden. (2002). Personalutbildning fo¨rsta halva˚ret 2002. Utbildning och Forskning [Staff training the first half of 2002. Education and research] (UF) 39.Statistiska Meddelanden (SM) 0202. O¨rebro, Sweden: SCB Tryck. Statistics Sweden. (2005).En longitudinell databas kring utbildning, inkomst och sysselsa¨ttning[A longitudinal database about education, income and employ-ment] 1990–2002 (LOUISE). O¨rebro, Sweden: Labour Market and Education Statistics Department, Statistics Sweden.

Tam, T. (1997). Sex segregation and occupational gender inequality in the United States: Devaluation or specialized training? American Journal of Sociology,102, 1652–1692.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (1991). Employment outlook(Chapter 5). Paris: Author.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2003). Employment outlook(Chapter 5). Paris: Author.

Tomaskovic-Devey, D., & Skaggs, S. (1999). An establishment-level test of the statistical discrimination hypothesis.Work and Occupations,26, 422–445. Tomaskovic-Devey, D., & Skaggs, S. (2002). Sex segregation, labor process

organization, and gender earnings inequality. American Journal of Sociology,108, 102–128.

Tomaskovic-Devey, D., Zimmer, C., Stainback, K., Robinson, C., Taylor, T., & McTague, T. (2006). Documenting desegregation: Segregation in American workplaces by race, ethnicity, and sex, 1966–2003. American Sociological Review,71, 565–588.

Veum, J. R. (1996). Gender and race differences in company training.Industrial Relations,35, 32–44.

Wooden, M., & VandenHeuvel, A. (1997). Gender discrimination in training: A note.British Journal of Industrial Relations,35, 627–633.

World Economic Forum. (2010). Global gender gap report 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

Yaish, M., & Stier, H. (2009). Gender inequality in job authority: A cross-national comparison of 26 countries.Work and Occupations,36, 343–366.

Author Biography