Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:06

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

An Exploration of Textbook Reading Behaviors

Rusty L. Juban & Tará Burnthorne Lopez

To cite this article: Rusty L. Juban & Tará Burnthorne Lopez (2013) An Exploration of Textbook Reading Behaviors, Journal of Education for Business, 88:6, 325-331, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.721023

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.721023

Published online: 26 Aug 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 181

View related articles

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.721023

An Exploration of Textbook Reading Behaviors

Rusty L. Juban and Tar´a Burnthorne Lopez

Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, Louisiana, USA

Using data from student surveys, the authors investigated reading behaviors and attitudes regarding the perceived usefulness of an assigned text and supplemental materials. The findings suggest that even when students are satisfied with the text, they are not likely to read the text as often as suggested, nor are they likely to use the supplemental materials (i.e., break out boxes, cases, and exercises) made available to them. Students do, however, demonstrate a preference toward PowerPoint slides over textbooks for class information. The authors propose several explanations for these behaviors, including the proliferation of information technology and new teaching pedagogies.

Keywords: education, reading, students, teaching, textbooks

As educators, we believe selecting a textbook is one of the most important things we do for a course. The reason for this is obvious; the course textbook has always been viewed by faculty and students as an integral feature of instruction and assessment (Becher, 1964). In some ways, the text is viewed as the professor in absentia, the source of knowledge when the professor is not there (Lichtenberg, 1992).

For those responsible for choosing textbooks, this choice has been made easier (or more difficult, depending on the perspective) by the increasing number of textbook options. It is difficult to avoid the weekly e-mails, flyers, and sam-ples distributed by publishers announcing new texts. For courses with traditionally large enrollments, the choices are numerous considering the authors and editions from which to choose. To add to the available choices, publishers have recently tried to cash in on the proliferation of e-readers and iPads to provide another option, digital textbooks, which can be purchased and downloaded (MacMillian, 2011).

An added concern when choosing a textbook is the cost for the student (Carbaugh & Gosh, 2005). As university tuition and fees have increased, so have the costs of textbooks. It is not uncommon for college students to spend over$200 on

books for a single course and more than$1,000 per semester

for books and supplies. Because state and federal funds go to pay for textbooks through student loans and grants, gov-ernment intervention in the cost of textbooks may not be

Correspondence should be addressed to Rusty L. Juban, Southeastern Louisiana University, Department of Management and Business Adminis-tration, SLU 10350, Hammond, LA 70402, USA. E-mail: rjuban@selu.edu

far off. In 2006, Congress commissioned a study to look at the rising costs of textbooks. The Government Accounting Office (2005) found that textbook prices rose 186% in the United States between 1986 and 2004, an average of around six percent per year.

An emerging question is whether students utilize text-books over other sources of information due to the ease of accessing information through technology. Technology such as smart phones and iPads has made access to the Internet almost limitless. Students are very comfortable accessing on-line sources, such as Wikipedia, for their information. It is possible to argue that textbooks may potentially become ob-solete or at least evolve into a format very different from the textbooks we have historically selected for classes.

Given the pressure to minimize costs coupled with an ex-panding number of textbook options and students’ increased access to information through technology, it is useful to ex-plore how students use textbooks and student perceptions of textbooks as a reference tool versus other information sources. For example, how do students view the different ancillary elements, such as breakout boxes and introductory cases, that publishers and authors increasingly add to new textbooks to help students learn? While these elements may excite publishers and college professors, an important ques-tion to address is how students are using the texts and readings suggested (and required) for a course.

The need for this type of inquiry was reinforced when, several years ago while deciding on a potential textbook for a principles of management course, we informally surveyed students on their perceptions of the current text and what im-provements could be made. While there were some general

326 R. L. JUBAN AND T. B. LOPEZ

comments about content and writing style, some students honestly admitted they had never read the text. When we asked why, several students felt that the lecture, notes, and PowerPoint’s (which most of our university’s faculty provide through our course management software) were sufficient until it came time to take an exam or do assignments. On those occasions, students said they did not have time to read through the entire chapter but skimmed it for the material they needed. We were dismayed by these responses; how-ever, this was not completely unexpected having sat (and sometimes slept) through more than our fair share of college classes. This led us to a question what we really knew about the reading behavior of our students. For example, how many students actually read the textbook? When students read the textbook, what material do they actually read and are stu-dents benefiting from the supplemental material included in the textbook? The purpose of this study was to explore these questions in the hope of better understanding student be-havior as it relates to textbook usage, student perceptions of textbooks, and how students are (and are not) benefitting from an assigned text.

LITERATURE REVIEW

It is generally accepted that textbooks are important for col-lecting and disseminating the available knowledge in an aca-demic field (Davis & Marquis, 2005; Stambaugh & Trank, 2010). Considering the large number of articles on meth-ods and pedagogies in business education, we assumed that researchers would have thoroughly explored the issue of text-book effectiveness and student reading behaviors. Our liter-ature search found that the majority of academic research centered on three themes: the veracity of current textbooks, the textbook adoption process, and the recent changes in technology and the publishing industry. The literature on textbook content is an assortment of works arguing the best approach for incorporating new knowledge and methods to teaching field specific knowledge (i.e., Laksmana & Tietz, 2008). If looked at separately, these contentious papers ap-pear to give the impression that the academic community should have little faith in the theories and models presented by textbook authors. However, we believe that the critical review of textbooks by the academic community is the very feature that establishes their validity. It is the obligation of faculty to scrutinize the information presented in textbooks, the same as a journal reviewer would an academic article sub-mitted for publication (Rotfeld & Terry, 2000). If faculty did not question the efficacy and currency of the material from profit-oriented publishers, faculty would have little trust in textbooks.

With regard to the textbook selection process, several stud-ies have examined how factors like costs, content, readability, and the availability supplemental material weigh in the

pro-fessors choice of a text (Lowry & Moser, 1995). Because the textbook adoption process is a faculty decision, surveys in this area have found that content is rated as the primary factor in textbook adoption (Silver, Stevens, Tiger, & Clow, 2011). While cost is an important issue, a survey by Silver, Stevens, and Clow (2012) found that faculty may resist ef-forts by administrators to force the adoption of lower cost (or open) textbooks. Another factor in adoption process related to textbook content is text readability. These studies have applied several well-accepted measures of writing level to predict adoption decisions (Razek & Cone, 1981; Villere & Stearns, 1976).

A more recent line of research on college textbook adop-tion concerns the effectiveness and adopadop-tion of new technol-ogy, such as electronic textbooks. According to an industry report, by 2016 electronic textbooks sales will make up 18% of total textbook sales. To accomplish this, analysts predict an average yearly increase in sales growth of approximately 150–200% over the next five years. There are several factors facilitating this dramatic growth including lower pricing for electronic textbooks, the growing availability of content, and the increasing number of students with access to e-readers.

We also broadened our literature search to include teach-ing pedagogies found in most texts such as the use of case studies, group learning activities, simulations and other in-teractive learning activities. These studies have provided di-rection for increasing student interaction, retention of ma-terial and student satisfaction. The majority of principles textbooks incorporate case studies, individual exercises, and group assignments and on the balance faculty perceive sup-plements as useful (Kennett-Hensel, Sneath, & Pressley, 2007). Some textbook publishers also incorporate additional content on websites and include quizzes, interactive assign-ments, videos, current readings, and programmed scenarios. Evaluating how students use these new technologies, Jonas and Norman (2011) found the critical predictor to be if a fac-ulty had made it a condition (or assignment) for the course.

While the current research in this area does make a sub-stantial contribution to how texts are evaluated and selected, these research topics are from the professor’s perspective, not the student’s. An exception was an early article which unobtrusively examined student reading behaviors by glu-ing pages of a textbook together and checkglu-ing at the end of the semester to determine if students had tampered with the pages (Friedman & Wilson, 1975). While novel, this study did not provide much insight into explaining student be-havior. Other exceptions are several recent studies that have examined student decisions to purchase textbooks. A sur-vey by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, a nonprofit consumer-advocacy organization, found that 70% of college students had not purchased a textbook at least once in their academic career due to increasing textbook costs (Redden, 2011). The survey, which consisted of 1,905 undergradu-ates on 13 campuses, did not measure student outcomes or

attempt to determine which predict the type of student most likely to forgo buying books because of high prices. The study also reported that 78% of students who reported not buying a textbook said they expected to perform worse in that class, even though some borrowed or shared the text-book. Additionally, Toerner (2006) offered some insight into student use of accounting textbooks.

RESEARCH QUESTION

Considering the knowledge that can be gained from read-ing the text, and the financial investments made by students, it may appear that the decision to read the text is obvious. However, most faculty have at least some anecdotal evidence that supports the idea that students may cut corners in class and read only what and when it is necessary. Again, ac-cording to the premise of the professor in absentia, is the textbook providing learning opportunities for the student? While most modern textbooks go beyond the presentation of basic knowledge and include methods to increase stu-dent retention of knowledge, the question that remains is how students use the text and the chapter contents. This leads to our research question: How are students using as-signed textbooks and what are their perceptions of the text, text supplements, and of other sources of subject-related information?

METHOD

To address the research question, we administered an attitu-dinal and behavioral survey to multiple sections of principals of management courses at an Association to Advance Colle-giate Schools of Business–accredited university. The survey examined student’s general perceptions and use of the as-signed textbook. In the application of the survey, students were assured anonymity and it was stressed that the intent of the survey was not to evaluate teacher effectiveness, but the content and use of textbooks. While there are limitations with the self-report method and students may have felt pres-sured to provide positive responses to please the instructor, as an exploratory study of this topic, using self-report of perceptions was a solid methodological choice. The survey was administered to five sections of a principles of manage-ment course open to juniors and older students. The prin-ciples of management text served as the students’ reference point for the survey. As noted previously, there is evidence that many students may decide not to purchase the textbook for a course (Redden, 2011). While this would affect stu-dent survey results on textbook usage, our university’s sit-uation with textbooks is advantageous in that textbooks are made available to students at the beginning of the semester and rental fees are included as a mandatory part of their tuition.

A total of 168 surveys were collected from five course sections that had a total enrollment of 201 students. The sur-vey sections included student perceptions of the textbook, student readership of the chapters and ancillary components, frequency with which students read the textbook, and student likelihood of using various resources for subject-matter in-formation. Student perceptions of the textbook were captured using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly dis-agree) to 5 (strongly agree). Readership and use of resources were captured using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Finally, to assess frequency of use, students were asked to indicate whether they read their text-book twice (or more) a week, once a week, twice a month, once a month, or only before exams.

RESULTS

The study yielded several interesting findings. To begin to understand how students use their textbooks, the students were asked when they were most likely to read the text. Forty-seven percent responded that they read the text once or twice a week (see Table 1). On the other hand, 40% responded that they read the textbook only before exams.

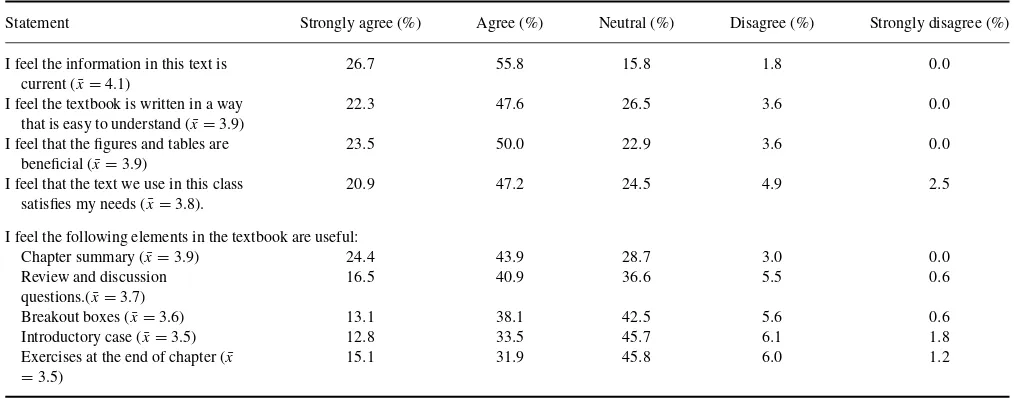

To understand if students read because they liked or dis-liked the textbook, it was important for us to understand stu-dent perceptions of the current textbook. The results showed that students held a favorable impression of the assigned textbook (see Table 2). Seventy percent of students strongly agreed or agreed that the information in the text was easy to understand ( ¯x =3.9). Eighty-two percent felt that the

infor-mation was current ( ¯x =4.1). Also, 68.1% of the students

agreed or strongly agreed that the information in the text satisfied their needs ( ¯x=.3.8).

We then divided the sample into two groups based on the frequency with which they read the textbook to determine whether the perceptions of the textbook varied between these groups. By splitting the sample into groups that read the text at least once a week (Group 1,n=76) and those that read the text less than once a week (Group 2,n=81), we found statistically significant differences between the two groups in all the satisfaction criteria based on independent samples

t-tests (see Table 3). The tests indicated that Group 1 always

TABLE 1

When Are Students Most Likely to Read the Textbook?

When are you most likely to read the textbook? %

Twice a week 8.64

Once a week 38.27

Twice a month 7.41

Once a month 5.56

Only before exams 40.12

328 R. L. JUBAN AND T. B. LOPEZ

TABLE 2

Satisfaction With Current Textbook and Usefulness of Text Supplements

Statement Strongly agree (%) Agree (%) Neutral (%) Disagree (%) Strongly disagree (%)

I feel the information in this text is current ( ¯x=4.1)

26.7 55.8 15.8 1.8 0.0

I feel the textbook is written in a way that is easy to understand ( ¯x=3.9)

22.3 47.6 26.5 3.6 0.0

I feel that the figures and tables are beneficial ( ¯x=3.9)

23.5 50.0 22.9 3.6 0.0

I feel that the text we use in this class satisfies my needs ( ¯x=3.8).

20.9 47.2 24.5 4.9 2.5

I feel the following elements in the textbook are useful:

Chapter summary ( ¯x=3.9) 24.4 43.9 28.7 3.0 0.0

Exercises at the end of chapter ( ¯x =3.5)

15.1 31.9 45.8 6.0 1.2

or often found the text to be easier to understand,t(155)=

4.21,p<.000, and more current,t(154)=2.46,p<.015,

than Group 2. Group 1 was also were more likely to say it satisfied their needs,t(152)=3.678,p<.000.

To investigate the usefulness of the supplemental sections of the text we asked students the extent to which they found introductory cases, break out boxes, the chapter summary, review and discussion questions, and exercises at the end of the chapter useful (see Table 2). These specific supplements were selected because they represented the supplements

in-TABLE 3

Satisfaction With and Usefulness of Current Textbook Based on Frequency of Reading Text

Group 1 Group 2

Statement (n=76) (n=76) t p

I feel the information in this text is current.

4.23 3.95 2.461 .015∗

I feel the textbook is written in a way that is easy to understand.

4.17 3.67 4.212 .000∗∗

I feel that the figures and tables are beneficial.

4.09 3.80 2.331 .021∗

I feel that the text we use in this class satisfies my needs.

4.08 3.56 3.678 .000∗∗

I feel the following elements in the textbook are useful:

Chapter summary 4.07 3.76 2.341 .021∗

Exercises at the end of chapter

3.72 3.33 2.837 .005∗∗

∗p≤.05.∗∗p≤.01.

cluded in the referenced principles of management textbook. The paired samplest-test suggests that students perceive the chapter summary to be a significantly more useful supple-ment to the text than the other supplesupple-ments. Review and discussion questions were deemed second in usefulness, sig-nificantly more useful than the remaining supplements.

Using the aforementioned two frequency of reading groups, we considered whether perceptions of the useful-ness of the text supplements varied between those who read the text frequently versus those who did not (Table 3). Paired samples t-tests revealed that there were significant differ-ences in perceptions of usefulness between the two groups for all supplements in the text. Students who read the text at least once a week (Group 1) perceived all supplements to be more useful than those who read less (Group 2).

When students were asked to indicate how often they read the text and the supplements in each chapter, the mean re-sponses varied from 3.4 to 2.3 on a 5-point scale (see Table 4). Of the students surveyed, 21.8% responded that they seldom or never read the main body of the chapter. Using paired samplest-test, it was found that students were more likely to read the main body of the chapter and the chapter summary, and less likely to read the other sections, such as exercises, cases, and breakout boxes. Interestingly, this supports a pre-viously discussed finding in which students indicated that the chapter summary was the most useful element of the text. Therefore, it follows that it would also be the section they are most likely to read.

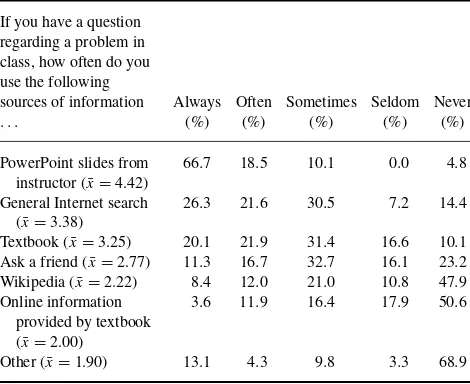

An important question in the current age of technology is whether students consider the textbook to be an important resource for class information. We asked students to indicate how often they use the textbook, PowerPoint slides from the instructor, online information from the textbook, Wikipedia, and general Internet search, a friend, or other sources when looking for information related to the class. Students

TABLE 4

Frequency Reading Textbook and Supplemental Material

Frequency Always Often Sometimes Seldom Never

reading (%) (%) (%) (%) (%)

Exercises at the end of chapter ( ¯x=2.27)

5.9 11.2 24.9 20.1 37.9

responded on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). A series of paired samples t-tests revealed several interesting findings (see Table 5). First, students were significantly more likely to use instructor-provided PowerPoint slides as a resource of finding informa-tion than the textbook,t(167)= −9.118,p<.000. Second,

students were equally likely to use the textbook as a re-source as they were to use a general Internet search,t(166)= −0.694,p<.489. They are less likely to use the remaining

sources.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Though exploratory in nature, our research to determine how students use textbooks and the supplemental material in text-books has contributed to knowledge in this area by offering

TABLE 5

Textbook as a Source for Class Information

If you have a question regarding a problem in class, how often do you use the following sources of information . . .

Always Often Sometimes Seldom Never

(%) (%) (%) (%) (%)

several relevant findings. At our university and many others, it is recommended that students spend 3 hr per week per 3-hr class studying in addition to in-class time. However, more than 50% of students in the first study stated that they read the textbook less than once a week. This led us to wonder: Do students value the text information or do students feel they already get the information in class and the text does not offer additional value? This finding may be a result of the perceived value of a rental textbook. Perhaps students who pay for texts would be more likely to value and use the textbook given the amount they paid.

Our research findings suggest that student decisions not to read the textbook are not related to negative attitudes about the textbook. In fact, the students had a generally positive attitude about the textbook. However, it is clear that students who read the textbook more frequently had a significantly more positive attitude toward the textbook as well as toward the chapter supplements. One possible explanation is that with increased exposure, students begin to appreciate the relevance and benefits of the textbook material.

The one supplemental element of the text stood out as be-ing perceived as the most useful and as most read by students was the chapter summary. Interestingly, review and discus-sion questions were rated as being second in usefulness after chapter summaries, but when we compared that with the fre-quency of use results, we found that review and discussion questions was among the least used supplements. That sug-gests that students recognize the usefulness of the review and discussion questions but avoid actually using them because of the increased effort and time required to answer the ques-tions. However, an interesting question for future research would be whether student behaviors toward the elements of the text would vary for more qualitative versus more quan-titative courses. In other words, students in a finance course may use end-of-chapter exercises more than those in a man-agement course.

Despite generally positive attitudes toward the textbook, students were more likely to use PowerPoint files as their source for class information. This is a cause for concern given that PowerPoint slides are a presentation tool, typically with an outline of the presentation content, and not a true in-depth reference source. Students who rely heavily on PowerPoint files will likely miss the details and depth necessary to truly understand most concepts. While PowerPoint files were the most common source for class information for students, the textbook and general Internet searches were the second most common. It is interesting that students are equally as likely to use each of these sources. It is possible to assume that due to the ease of access to information, students would be more likely to use the Internet to locate class information.

CONCLUSIONS

As faculty, we believe it is our responsibility to evaluate the effectiveness of our teaching and our methods. However, it

330 R. L. JUBAN AND T. B. LOPEZ

may be time to re-examine the value of textbooks if students do not utilize them or their supplements. There can be little argument that if textbooks are not regularly read by students, then they are not an effective means of communicating mate-rial to students. This does not suggest that textbooks should not be a part of college reading assignments; this research does not question that texts are still a trusted repository of tested research and knowledge in the field. In addition, many textbooks go beyond the presentation of material to include exercises and activities to help students further develop their skills and learning. However, one of the most important el-ements of the teaching equation, the willingness of students to actually read the material contained in the text, is often assumed and unmeasured.

Results from our survey show that a sizable portion of students are not regularly reading the textbook and some may never read it at all. In addition, the supplemental mate-rial that is designed to aid students in retaining information is often ignored. From the findings presented here, we be-lieve that faculty who select college textbooks for courses need to critically rethink how reading assignments are ap-proached in college courses. Today’s college students may be overloaded with all of the information sources they have available. It’s possible that students ignore the value of using a text because of all the information available to them. As our research shows, they are equally or more likely to use instructor-provided PowerPoint files and information from web searches. Another explanation may be that Generation Y students are less tolerant of textbooks that follow a structured outline and would prefer to use more condensed forms of in-formation, such as chapter summaries and PowerPoint files, or electronic media that allows them to search for key terms. The research presented here is not intended to provide faculty with an alternative approach to course assigned text-books or other reading assignments, instead we believe that it points out a potential flaw in assuming that all students diligently read course material out of some assumed sense of obligation. As the costs of textbooks continue to rise, fac-ulty may want to consider the value that a textbook brings to students (i.e. using a cost-benefit analysis for requiring a textbook). After assessing the benefit of assigning a tra-ditional text, which could cost several hundred dollars and may not generate much student interest, some faculty may be encouraged to venture into other forms of reading ma-terial. E-textbooks are less expensive than hardbound texts and offer the advantage of media searches and more interac-tive supplements, including video and audio files. But, these electronic texts may suffer from some of the same problems as other traditionally structured texts, that is, lack of student interest. Some faculty may choose to forego a text altogether and take advantage of free information available on the Inter-net. However, we should point out that information from the Internet comes in a variety of formats. This could cause prob-lems as students are forced to sift through unorganized and sometimes outdated information. Another hazard involved

when using free information for learning purposes is that it is not validated by scholars in the field and subject to change by the provider.

It is our hope that the findings presented here will create more interest in student reading behaviors. It would be ben-eficial for faculty to understand what compels some students read the text, while others ignore it. Some of these variables may be student centered or driven by the demands of the course. These questions may be rooted in the criteria that make up a good versus a poor performing student. Also, for faculty who want to move away from traditional text, there are a variety of factors that would need to be identified to in choosing the best option. Whether it is time to consider replacing textbooks with other forms of reading, or chang-ing how we give readchang-ing assignments, we believe that it is questioning the effectiveness of our methods that will make us better educators.

REFERENCES

Becher, P. (1964). Management by the textbook.Management of Personnel Quarterly,2(4), 14–19.

Carbaugh, R., & Ghosh, K. (2005). Are textbooks priced fairly?Challenge,

48(5), 95–112.

Davis, G., & Marquis, C. (2005). Prospects for organizational theory in the early twenty-first century: Institutional fields and mechanisms. Organi-zational Science,16, 332–343.

Friedman, M., & Wilson, W. (1975). Applications of unobtrusive measures to study textbook usage by college students.Journal of Applied Psychology,

60, 659–663.

Government Accounting Office. (2005).Enhanced offerings appear to drive recent price increases. Washington, DC: Author.

Jonas, G., & Norman, C. (2011). Textbook websites: User technol-ogy acceptance behavior. Behaviour & Information Technology, 30, 147–159.

Kennett-Hensel, P., Sneath, J., & Pressley, M. (2007). Powerpoint and other publisher provided supplemental materials: Oh Lord, what have we done?

Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education,10, 1–11.

Laksmana, I., & Tietz, W. (2008). Temporal, cross-sectional, and time-lag analysis of managerial and cost accounting textbooks.Accounting Education,17, 291–312.

Lichtenberg, J. (1992). The new paradox of the college textbook.Change,

24(5), 10–18.

Lowry, J., & Moser, W. (1995). Textbook selection: A multistep approach.

Marketing Education Review,5(3), 21–28.

MacMillian, B. (2011, June 16). Textbook 2.0.Business Week,28. Razek, J. R., & Cone, R. (1981). Readability of business communication

textbooks: An empirical study.Journal of Business Communication,18, 33–40.

Redden, M. (2011, August 23). 7 in 10 students have skipped buying a textbook because of its costs, survey finds.Chronicle of Higher Educa-tion.Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/7-in-10-Students-Have-Skipped/128785/

Rotfeld, H., & Terry, C. (2000). The textbook effect: Conventional wisdom, myth, and error in marketing.Journal of Marketing,64, 122–126. Silver, L., Stevens, R., & Clow, K. (2012). Marketing professors’

perspec-tives on the cost of college textbooks: A pilot study.Journal of Education for Business,87, 1–6.

Silver, L., Stevens, R., Tiger, A., & Clow, K. (2011). Quantitative methods professors’ persectives on the cost of college textbooks.Academy of Information & Management Sciences Journal,14, 39–55.

Spinks, N., & Wells, B. (1993). Readability: A textbook selection criterion.

Journal of Education for Business,69, 83–88.

Stambaugh, J., & Trank, C. (2010). Not so simple, Integrating new re-search into textbooks.Academy of Management Learning & Education,

9, 663–681.

Toerner, M. (2006). Student readership of supplemental, In-chapter material in introductory accounting textbooks.Journal of Education for Business,

82, 112–117.

Villere, M., & Stearns, G. (1976). The readability of organizational behavior textbooks.Academy of Management Journal,19, 132–137.