EMPOWERING EFL STUDENTS IN WRITING

THROUGH PORTFOLIO-BASED INSTRUCTION

A Dissertation

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education

By:

SUDARYA PERMANA NIM 0707164

ENGLISH EDUCATION PROGRAM

SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES

INDONESIA UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION

I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other works, and that to the best of my knowledge the dissertation contains no material previously written or published by another person, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text of the dissertation.

Signed: ……….

By: Sudarya Permana

NIM 0707164

APPROVED BY:

Supervisor

Prof. A. Chaedar Alwasilah, M.A., Ph.D. NIP. 195303301980021001

Co-Supervisor

Emi Emilia, M.Ed., Ph.D. NIP. 196609161990012001

Member

By: Sudarya Permana

NIM 0707164

ACKNOWLEDGED BY:

The Head of the English Education Study Program

The present study is about empowering EFL students in writing through portfolios-based instruction. In this study, portfolios were conceptualized as an approach to teaching writing.

They were defined as a selected collection of students’ works that exhibited their efforts, progress, and achievements in an English writing class in one semester. Meanwhile, the term

‘empowerment’ was understood as the improvement in writing involving two aspects: lingual

and personal empowerment. Lingual empowerment was the improvement of writing where students could produce an effective or proficient text, whereas personal empowerment was concerned with the improvement of writing in which students showed a positive attitude in developing the text and towards their writing performance.

The present study was conducted in an English writing class at the tertiary level including fifteen student teachers as the participants. The study took place in one semester, and it employed an action research design. Data were gained from student text analyses, classroom observations, the use of questionnaire, and interview. Data were analyzed using a qualitative and quantitative strategy. The qualitative strategy was undertaken through text analyses and coding in data of student texts, classroom observations, and interview. On the other hand, the quantitative strategy was based on descriptive statistics with frequency counts to data of questionnaire.

Table of Contents

Statement of Authorship ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Empowering Efl Students In Writing Through Portfolio-Based Instruction . Error! Bookmark not defined.

Abstract ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Acknowledgements ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

Table of Contents ... i

List of Tables... iv

List of Diagrams ... v

List of Figures ... 6 Chapter One Introduction ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.1 Background of the Study ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.2 Purposes of the Study... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.3 Research Questions ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.4 EFL Writing Instruction in the Research Site ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

1.5 Significance of the Study ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.6 Organization of the Dissertation ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Chapter Two Literature Review ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.1 Introduction ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.2 Portfolios ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.2.1 The Concept of Portfolios Emphasized in the Present Study ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

2.2.2 Basic Principles of Portfolio-Based Instruction Focused-on in the Error! Bookmark not defined.

2.2.3 Types of Portfolios ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.2.4 Advantages of Portfolios ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.2.5 Issues in Portfolios ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.2.6 Assessment of Portfolios ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.2.7 Previous Relevant Studies about Portfolios ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

2.3.2 Empowerment Process in Relation to the Present Study ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

2.3.3 The Relationship between Portfolios and Empowerment ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

2.3.4 The Relationship between Writing and Empowerment ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

2.4 Writing ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.4.1 The Concept of Writing ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2.4.2 The Relationship between Portfolios and Writing ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

2.4.3 Types of Writing Produced by Students in the Present Study ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

2.5 Conclusion ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Chapter Three Methodology ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.1 Introduction ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.2 Pilot Study ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.3 Research Design... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.4 Setting ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.5 Participants ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.6 Data Collection Methods ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.6.1 Student Text Analyses... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.6.2 Classroom Observation ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.6.3 Use of Questionnaire ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.6.4 Interview ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.7 Data Analysis Methods ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.8 Conclusion ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Chapter Four The Teaching Program ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

4.1 Introduction ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 4.2 The Planning Phase ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 4.3 The Acting Phase ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 4.3.1 The Preliminary Stage ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 4.4 The Main Phase... Error! Bookmark not defined.

4.4.1 Writing with Free Topic (Freewriting) ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

4.4.3 Writing an Opinion about Controversial Issues .... Error! Bookmark not defined.

4.5 The Observing Phase ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 4.6 The Reflecting Phase ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 4.7 Conclusion ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Chapter Five Text Analyses ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

5.1 Introduction ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 5.2 Descriptions of Texts Produced by Students in the Teaching Program Depicting the Tendency of Emergence of Empowerment in Writing... Error! Bookmark not defined.

5.3 Analyses of Texts ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 5.3.1 Texts Produced by Lala ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 5.3.2 Texts Produced by Anggi ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 5.3.3 Texts Produced by Rita ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 5.4 Conclusion ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Chapter Six Discussions Of Questionnaire And Interview Data ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

6.1. Introduction ... Error! Bookmark not defined. 6.2 Discussions of Data from the First Interview and Questionnaire: How the Program Empowered EFL Learners... Error! Bookmark not defined. 6.2.1 Students’ Response (Attitude) towards the Teaching ProgramError! Bookmark not defined.

6.3 Discussions of Data from the Second Interview: The Difficulties of the Implementation of Portfolio-Based Instruction in Writing ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

Appendix 2: The Classroom Observer’s Notes ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Appendix 3: The Researcher’s Reeflective Notes . Error! Bookmark not defined. Appendix 4: Questionnaire ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Appendix 5: Questionnaire ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Appendix 6: Student And Lecturer Problems In The Teaching Program ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

Appendix 7: Condensed Version Of Interview Data On Student And Lecturer Problems In The Teaching Program ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Appendix 8: Reflective Questions Used In The Teaching Program ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

Appendix 9: Samples Of Student Journals Based On Reflective Questions

Employed In This Study Originally Quoted By The Researcher Error! Bookmark not defined.

Appendix 10: Samples Of Student Texts Which Were Not Discussed In The Text Analyses ... Error! Bookmark not defined. Curriculum Vitae ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

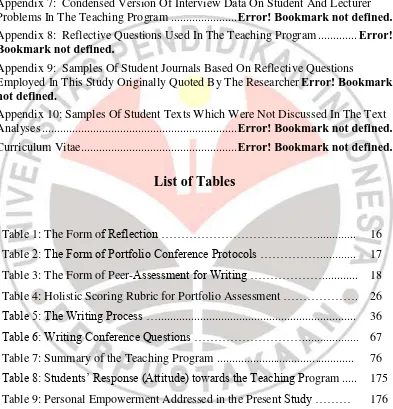

List of Tables

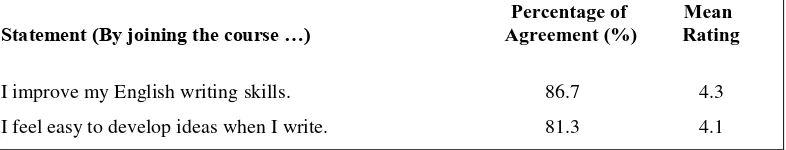

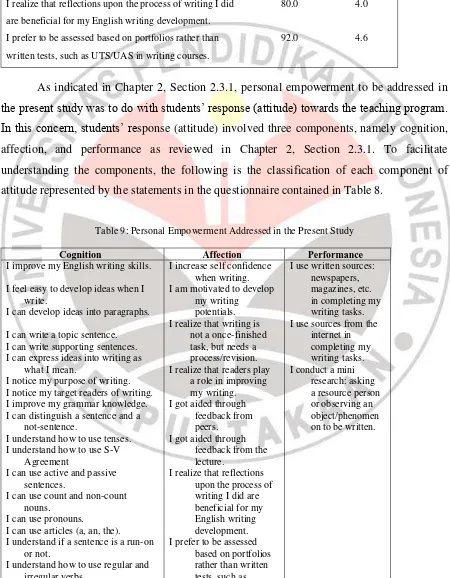

Table 1: The Form of Reflection ………... Table 2: The Form of Portfolio Conference Protocols ………... Table 3: The Form of Peer-Assessment for Writing ………... Table 4: Holistic Scoring Rubric for Portfolio Assessment ………. Table 5: The Writing Process …... Table 6: Writing Conference Questions ………... Table 7: Summary of the Teaching Program ... Table 8: Students’ Response (Attitude) towards the Teaching Program ... Table 9: Personal Empowerment Addressed in the Present Study ………

List of Diagrams

Diagram 1: The Comparison of Portfolio-Based Instruction

Chapter One

Introduction

1.1 Background of the Study

In this global era, writing plays an important role in human life, either individually or collectively. Through writing, an individual can express his or her ideas about a phenomenon he or she feels. Writing, therefore, has been considered as a gateway for success in many aspects of life: academia, new workplace, global economy, and participatory democracy (The National Writing Project of America, 2006: 2). In this concern, Weigle points out:

Writing, which was once considered the domain of the elite and well-educated, has become an essential tool for people of all walks of life in today’s global community. Whether used in reporting analyses of current events for newspapers or web pages, composing academic essays, business reports, letters, or e-mail messages, the ability to write effectively allows individuals from different cultures and backgrounds to communicate. Furthermore, it is now widely recognized that writing plays a vital role not only in conveying information, but also in transforming knowledge to create new knowledge (2002: x).

Hence, today writing is not the dominance of well-educated people anymore in the sense that it needed a high level of education for writing skills and activities, but everybody now is involved in writing in their daily life, for example, sending a short message service (SMS) or an e-mail to communicate across ethnics and cultures. More importantly, in the context of scientific and technological development, writing has been crucial in building a new civilization through the transformation and creation of new knowledge.

Academic disciplines have their own ways of organizing knowledge, and the ways in which people in different subject areas write about their subjects are actually part of the subject itself and something that has to be learnt (1997: 1).

Thus, although writing has not been the domain of the elite and well-educated people, in the academic context, in order to write effectively, writing must be learned. This is because the subject areas are various so that the objective of writing should be adjusted with the content of the knowledge itself. In this relation, the document of the National Writing Project of America states:

Effective writing skills are important in all stages of life from early education to future employment. In the business world, as well as in school, students must convey complex ideas and information in a clear, succinct manner. Inadequate writing skills, therefore, could inhibit achievement across the curriculum and in future careers, while proficient writing skills helps students convey ideas, deliver instructions, analyze information, and motivate others (2006: 3)

Nevertheless, despite the significance of writing for students’ academic

success, writing, either in native or foreign language, has been often neglected in the language classrooms (Alwasilah, 2001; Williams, 2005; Aydin, 2010). Writing is among the most important skills that students need to develop (Hyland, 2003: xv). In addition, according to Alwasilah (2001), it is the language skill often reported as most wanted by students from elementary to graduate schools. With regard to language education, according to Hyland (2003: xv), the ability to teach writing is central to the expertise of a well-trained language teacher. Nonetheless, compared to other skills—reading, listening, and speaking—writing has been considered most difficult, either for students to acquire or for teachers to teach (Alwasilah, 2001: 24; see also Ariyanti, 2010: 91; Nurjanah, 2011: 81). The fact that writing is a difficult subject for most students is also confirmed by Emilia:

The description above shows the urgency to help students improve their writing skills as writing can lead students to empowerment. According to Jordan (2003), through writing students will come to two kinds of empowerment: practical and political empowerment. Practical empowerment is associated with improving writing skills, whereas political empowerment with increasing critical awareness. Regarding this, Kohonen et.al (2000) distinguishes two types of empowerment in writing: lingual and personal empowerment. Lingual empowerment concerns students’ ownership of their language knowledge and skills for a variety of communicative purposes, whereas personal empowerment

is concerned with students’ active role in controlling the process of writing that

involves psychological factors, such as self confidence, motivation, and soon. In view of that empowerment is a broad concept employed by many areas of subject (see van Lier, 1996; Page & Czuba, 1999; Jordan, 2003; Hur, 2006) and its relevance with the purposes of the study, the present study was only focused on lingual and personal empowerment in writing.

Based on the researcher’s pilot study in the research site, it was found that

most students were not satisfied with the writing instruction. The dissatisfaction was to do with several reasons, among others, less time to complete the writing task, lower motivation to join the class, and lack of creativity due to topic limitations by the lecturer.

In the research site the writing instruction seemed to still follow the traditional approach where students produced “a single piece of timed writing

with no choice of topic and no opportunities for revision” (Hyland, 2003: 233). In

other words, the writing instruction was not much concerned with the process of writing including prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing (Tompkins, 2008: 7) as implemented in the present study. Thus, a teaching program which gives students an opportunity to go through a process of writing is really important.

students’ writing collection that demonstrated the process of their writing in

producing a particular piece of text. The process of student writing was represented through writing drafts from the first to final drafts. In this context, Chamot et.al (1999) claim that one advantage of involving portfolios in learning is that they can provide evidence of growth in many different dimensions of learning, one of which is through the recognition of writing drafts produced by students. In this way, students can identify the strengths and weaknesses of their writing that will finally empower them in writing. This potential advantage of portfolios had made the researcher conduct the present study.

1.2 Purposes of the Study

Based on the above background, the purposes of the present study were: (1) To find out how a portfolio-based instruction can empower EFL students in

writing at the tertiary level in terms of lingual and personal aspects,

(2) To address the problems encountered by EFL students and the lecturer in implementing a portfolio-based instruction in an EFL context.

1.3 Research Questions

Based on the purposes of the study, this study addressed the following questions:

(1) How can a portfolio-based instruction empower EFL students in writing at the tertiary level in terms of lingual and personal aspects?

(2) What problems may EFL students and the lecturer encounter in implementing a portfolio-based instruction in an EFL context?

1.4 EFL Writing Instruction in the Research Site

Writing I provides basic writing skills at the levels of sentences and paragraphs in many texts and functional texts by paying attention to social functions, elements and structures of meaning, and linguistic features of related texts. This subject also teaches subskills of writing, such as topic sentence, supporting sentences, paragraph development or organization, and writing mechanism. The text types to be taught are descriptive texts, anecdotes, procedures, and recounts, whereas the functional texts include form-fillings, messages, letters, memos, comic strips, advertisements, and recipes. All of the text types are presented on the themes of people, things, college life, places, past experience, and food.

Writing II provides intermediate writing skills at the levels of sentences, paragraphs, and short texts at the variety of text types by paying attention on social functions, elements and structures of meaning, and linguistic features of related texts. This subject also teaches writing subskills, like topic sentence, supporting sentences, paragraph development or organization, and writing mechanism. The text types to be taught are descriptive texts, spoofs, procedures, narratives, and reports. The functional texts consist of short stories, notices, tables, and manuals. These all are presented on the themes of weather, sports, entertainments, flora, and fauna.

Writing III provides advanced writing skills at the variety of texts, namely explanation, discussion, exposition, and review. The functional texts to be taught involve news items, articles, essays, and reviews with regard to social functions, elements and structures of meaning, and linguistic features of related texts. The themes include cultures, global warming, education, and media.

From the descriptions about writing instruction above, it can be seen that the writing instruction in the research site emphasizes more types of texts. In this case, the types of texts have already been determined in advance. Thus, students are not given an opportunity to freely choose the topic that they want to write. Besides, it was not yet found whether the production of a particular text type in the research site was conducted through a process-based approach including prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing (Tompkins, 2008) as implemented in the present study. This is because the syllabi that described in details about the general descriptions of the writing subjects were not found. Paying into account about such a condition of the writing instruction in the research site, the researcher proposed to conduct the present study.

1.5 Significance of the Study

provide new insights with empirical evidence useful for the development of portfolio-based instruction. In this case, the research findings can become a reference when portfolios will be made as the policy in the practice of education, especially in an EFL context.

At the practical level, the present study will serve several stakeholders. First, the institution where the present study was undertaken will benefit from it.

Since there have been very few studies on portfolios in the institution, the present study can be of great importance in providing teachers with implementation of a portfolio-based instruction in EFL classrooms, especially in writing instruction. Second, English lecturers, teachers, or practitioners will also take advantage of the

present study. They will have insights on how to empower EFL students in writing through the implementation of portfolio-based instruction. Here, EFL students are supposed to be able to improve their capability in writing. The knowledge of portfolio-based instruction can be taken into account when the English lecturers, teachers, or practitioners are engaging with their professional activities. Last, the English curriculum developers and textbook writers will be assisted with the present study. The results of the study can be great insights and knowledge for designing English textbooks where portfolio-based instruction is employed, especially in writing instruction.

1.6 Organization of the Dissertation

included into the teaching program as well as analyses of some parts of data

gained, especially from students’ reflective notes or journals and observations. Chapter 5 provides a discussion of students’ text analyses in reference to holistic

scoring rubric to observe students’ empowerment, particularly lingual empowerment of their writing. Chapter 6 offers a discussion of student

questionnaire and interview data to portray students’ empowerment, peculiarly

Chapter Three

Methodology

3.1 Introduction

This chapter reviews the methodology employed in the present study. The discussion includes the pilot study, research design, setting, participants, data collection methods, and data analysis methods. Data collection methods involve student text analysis, classroom observation, use of a questionnaire, and interview. Data analysis methods use qualitative and quantitative strategies. The qualitative strategy was undertaken through text analysis and coding, whereas the quantitative strategy was based on descriptive statistics with frequency counts.

3.2 Pilot Study

The pilot study was a preliminary study carried out prior to the present study. The aim was to assure the necessity of the implementation of the present study. According to Locke, Spirduso, & Silverman (2001: 74), the pilot study is useful in research, but it is often neglected by the researcher. Locke, Spirduso, & Silverman (2001: 75) emphasize that “a pilot study is a pilot study” and the purpose of which is “the practicality of proposed operations, not the creation of empirical truth”. Alwasilah (2000: 99) argues that the pilot study is important because of some reasons: (a) to experience the implication of emergent-theory approach, that is how a theory emerges by its own accord, not borrowing from the existing theories, and (b) to explore the phenomena or the observed theories.

In relation to the present study, a pilot study was undertaken with the following procedures:

Choosing two sites of pilot study, namely universities, in which one was considered to have implemented portfolio-based instruction in writing course (University A) and the other one was to have not (University B).

instruction. In so doing, the researcher was also willing to recognize students‟ response towards the writing course.

From the pilot study, it was found that the implementation of portfolio-based instruction with self-assessment, peer-assessment, and clearly stated criteria as its basic principles (see O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996; Genesee & Upshur, 1996; Ekbatani & Pierson, 2000; Lynch & Shaw, 2005) was more obviously observed in University A than in University B. In other words, University A had been more portfolio-oriented in writing instruction than University B. This can be seen from the diagram below:

Diagram 1: The Comparison of Portfolio-Based Instruction Implementation in University A and University B

Note:

SA = Self-assessment PA = Peer-assessment

SI = Student involvement for clearly stated criteria

Another considerable finding of the pilot study was that the University A students tended to be more motivated in joining the writing course than the University B students. This is relevant with one aspect to be addressed in the present study in that it can generate personal empowerment in which one of the indicators is affection as indicated in Table 9. In this concern, the majority of the University A students felt motivated and confident that they were capable of writing English texts after the course. This can be recognized from one of the University A students‟ responses originally quoted by the researcher:

“Perkuliahan ini unik dan menyenangkan. Selama mengikuti kelas writing, kelas inilah yang dapat memotivasi saya untuk menulis, bukan hanya dijejali pelajaran writing

sebagai formalitas dalam kurikulum dan bukan hanya masalah kesalahan grammar yang dapat membuat saya down dalam menulis. Kelas ini kelas yang mengajarkan dan memotivasi saya untuk menulis dan saya merasa hasil karya saya dihargai dengan dikoreksi sendiri dan teman-teman sejawat. Dosen pun sering memotivasi untuk memasukkan hasil tulisan kami ke surat kabar atau majalah publik dan hal itu membuat

saya „greget‟ untuk menulis dan mencobanya. Intinya, saya bisa katakan „Inilah kelas writingyang sesungguhnya …”

(This course is unique and fun. For the writing class I have joined so far, it is this class that can motivate me to write, not only stuffed by writing subject as the formality of curriculum and not only about grammatical mistakes that can make me discouraged to write. This is the class that teaches and motivates me to write and I feel that my pieces of work are valued and appreciated through self and peer reviews. The lecturer also often motivates us to send our papers to news media, newspapers or magazines, and this has become a strong urge for me to write and to try it. In brief, I can say that „this is a real writing class)

Nevertheless, in the pilot study, the researcher had not been able to find out whether the University A students‟ texts had met the criteria of effective or proficient writing. In this respect, it was assumed that feeling motivated and being capable of writing English texts did not automatically guarantee that students had produced an effective or proficient English text. In addition, the present study was also concerned with the investigation of other aspects of student personal or individual empowerment that could be generated through portfolio-based instruction in an EFL context.

3.3 Research Design

action research, the improvement can be also directed to the lecturer in which he or she has better understanding of his or her practices (see Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007: 298).

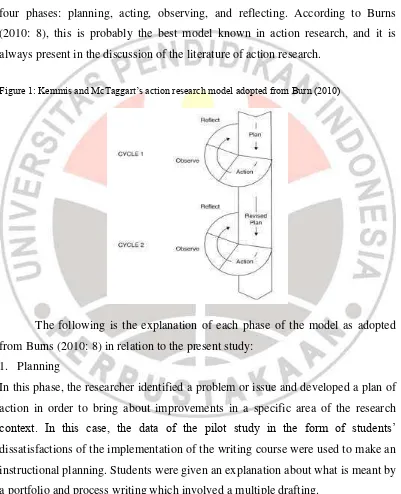

In the present study, the action research was conducted in reference to the model developed by Kemmis & McTaggart (Burns, 2008: 8). The model contains four phases: planning, acting, observing, and reflecting. According to Burns (2010: 8), this is probably the best model known in action research, and it is always present in the discussion of the literature of action research.

Figure 1: Kemmis and McTaggart‟s action research model adopted from Burn (2010)

The following is the explanation of each phase of the model as adopted from Burns (2010: 8) in relation to the present study:

1. Planning

2. Acting

In this phase, the researcher implemented the instructional planning. Regarding this, the researcher carried out twenty two meetings during one semester with three topics of writing pieces produced by students involving a six-time drafting. Thus, the data in this phase were the texts written by students in the period of one semester.

3. Observing

This is a phase where the researcher was involved in data collection observing systematically the effects of the action and documenting the context, actions, and opinions about what are happening. Concerning this study, the researcher conducted a classroom observation where students were involved in the process of writing starting from prewriting to publishing the texts as indicated Section 2.4.1 of Chapter 2. After each meeting, the researcher identified what worked and what did not work to find out what were needed to improve in the next steps. The classroom observation also involved a classroom observer to work collaboratively to complementarily support the data which were not well observed by the researcher. The classroom observer acted as a critical friend to the researcher (Kember: 130, 2000; Burns, 2010: 44). Thus, in this phase, the data were field notes written by the researcher and the classroom observer about the implementation of the teaching program in each meeting. The field notes can be seen in Appendices 2 and 3.

4. Reflecting

3.4 Setting

The study was carried out at the English department of a university in Indonesia in the first semester of academic year 2010/2011. The department has two major study programs: educational study program, whose graduates are prepared to become English teachers (to which the participants of the present study belonged) and literary study program, whose graduates are prepared to be involved in non-teaching jobs.

There were several reasons why this research site, at tertiary level of education, was chosen. Firstly, as one of the faculty members of the department, it was hoped that this would facilitate the researcher to get access easily to the research site. This, therefore, would increase the feasibility of the study. The researcher‟s familiarity with the students (in which they were the participants of the present study) was expected to be able to build good relationships with the participants, which was needed in the study. In this context, according to Alwasilah (2000: 201), it is the researcher who needs the participants, not vice versa, so the researcher must be able to establish good relationships with the participants.

Secondly, the present study was aimed to improve the instructional practice, namely English writing instruction so that action research was used as the design. Because the researcher is the faculty member of the department, it would be more meaningful for the researcher to conduct the research in the department so that the improvement can be contributed to the department. Besides, the researcher had more access for the sample class, which formally needs several requirements, either administratively or financially. In the present study, the role of the researcher was a teacher-researcher (Richards, 2003: 128) or the teacher as researcher (van Lier, 1996: 25) or the researcher acting as teacher (Stake, 1995 as cited in Emilia, 2005: 74). Due to some weaknesses of a teacher-researcher role (Richards, 2003: 128), this study involved a classroom observer who worked collaboratively with the researcher (Burns, 2010: 44).

(Missouri Southern State University-Joplin-Division of Lifelong Learning, 2002), the present study chose the research site at tertiary level of education. This is because of the assumption that tertiary levels of education are not interested in having students spend time in classes relearning what they know or have learned through “life experience” (Missouri Southern State University-Joplin-Division of Lifelong Learning, 2002).

3.5 Participants

The present study involved one single group of English writing course consisting of fifteen students of undergraduate program taking Writing II subject. All of them came from the educational program that had passed Writing I subject as the prerequisite for students to join Writing II subject as regulated in the curriculum of the department.

The selection of the participants was not purposive, but at random. In this case, the researcher did not determine which students were going to be involved in the study. The researcher just accepted the students for the Writing II class as assigned by the institution (department). In view of that what is probably found suitable in one context or case may not necessarily be found appropriate in another (Clark, 1987), it was considered that one single group of English writing course was already representative for the present study.

3.6 Data Collection Methods

Dawson, 2009; Burns, 2010; Stake, 2010). Through triangulation, a researcher is in the process of “cross-checking and strengthening the information” (Burns, 2010: 95) or “looking again and again, several times” (Stake, 2010: 123) of the observed phenomena. According to Merriam (1988: 69), in approaching the triangulation, the researcher combines different methods in such a way: interviews, observations, and physical evidence to study the same unit.

3.6.1 Student Text Analyses

In this study, students‟ texts were gained from their writing tasks during the teaching program. The writing tasks were student documents employed in the present study to observe the development of students‟ writing skills. This was aimed to find out whether or not the student writing skills improved after a multiple drafting process. Concerning the use of writing samples in research, Marshall & Rossman (1999: 116) stipulate that samples of writing that discuss a topic are very informative sources. According to Marshall & Rossman, a document is an unobtrusive material which is rich of information in portraying the values and beliefs of participants in the setting. This is suggested by Merriam (1988: 104) saying that the analysis of documents has been chosen mostly because of the use of written materials.

3.6.2 Classroom Observation

In this study, classroom observation was a phase of teaching where the researcher acted as a participant observer. Regarding the cycles of action research applied in the study, the observations were conducted in every classical meeting to investigate students‟ behavior and attitudes. For every classical meeting, the researcher analyzed the strengths and weaknesses to be considered in the following sessions. The weaknesses found out in one session were made as the problems to be improved in the next sessions involving twenty two classroom observations.

In view of that the role of the researcher acted as teacher has some weaknesses, one of which is less easy to organize the research setting (Wallace, 1998: 106), the researcher involved the classroom observer—who was the researcher‟s colleague—to document all the happenings during the classroom activities. In this case, the classroom observer worked collaboratively with the researcher (Burns, 2010: 44). According to Wallace (1998: 106), such collaboration greatly extends the scope of what can be observed.

The main goal of a classroom observation was also to increase the researcher‟s sensitivity to his or her own classroom behavior and its effects to students (Allwright, 1988: 76). Through observation, the researcher can view by himself tacit understanding which cannot be discovered without involving it, such as in interview or document analysis (Alwasilah, 2000: 155; Maxwell, 1996: 76). In this line, Maxwell points out:

Observation often enables you to draw inferences about someone‟s meaning and perspective that you couldn‟t obtain by relying exclusively on interview data. This is particularly true of getting at tacit understandings and theory-in-use, as well as aspects of the participants‟ perspective that they are reluctant to state directly in interviews (1996: 76).

3.6.3 Use of Questionnaire

Besides from student texts and classroom observations, the data were also gained from questionnaires. In this study, questionnaires were used to find out students‟ perceptions about the teaching program established for the whole semester. Pertinent to this, Marshall & Rossman (2006: 125) state that the administration of questionnaire is undertaken to “learn about the distribution of characteristics, attitudes, or beliefs”.

Regarding the present study, questionnaires were designed in two types. The first one was a closed or structured questionnaire. This kind of questionnaire is a highly structured data collection instrument which aims to obtain data in statistical or quantitative ways (Dörnyei, 2003: 14; see also Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007: 321; Marshall & Rossman, 2006: 125-126; Wallace, 1998: 124). In this case, the students were asked the same questions (Stake, 2010: 99) to portray statistically “the variability of certain features in a population” (Marshall & Rossman, 2006: 125). In the present study, this structured questionnaire was designed on the basis of Likert scales, which has been the most commonly used scaling technique (Dörnyei, 2003: 36) as indicated in Appendix 5.

Meanwhile, the second type of questionnaire used in this study was an open-ended questionnaire as indicated in Appendix 4. This type of questionnaire was utilized to provide data in qualitative or exploratory ways (Dörnyei, 2003: 14). In this case, according to Dörnyei (2003: 47), by permitting greater freedom of expression to students, this kind of questionnaire can provide a far greater richness than fully quantitative data. This was also stated by Oppenheim that the freedom of expression that it gives to the students is the chief advantage of the open-ended questionnaire (1966: 41). Following Oppenheim (1992), Dörnyei (2003: 47) points out that, in some cases, the same questions can be asked both in an open and closed form.

This was aimed to check the workability of the questionnaires whether the instructions were clear and easy to follow, whether the questions were clear, whether the participants were able to answer all the questions, and whether the participants found any questions embarrassing, irrelevant, patronizing, or irritating (Wallace, 1998: 133).

3.6.4 Interview

The interview was used to validate data from the other sources. It was conducted twice. The first one was undertaken after the completion of one selected topic—in which one selected topic was completed through a six-time drafting, whereas the second one was done after the accomplishment of all the topics that was at the end of the semester. The first interview was to do with reflective questions to portray students‟ perception and progress in producing one selected text as indicated in Appendix 6. The second interview concerned students‟ perception about the difficulties encountered by students and the lecturer during the teaching program as indicated in Appendix 8.

The use of interviews has been a common instrument in qualitative study (Seidman, 2006; Kvale, 1996; Merriam, 1988). In general, it occurs in a conversation, but a purposeful conversation (Marshall & Rossman, 2006/1999; Merriam, 1988). Concerning this study, combined with classroom observation (Marshall & Rossman, 2006: 102) or made complementary with questionnaires (Wallace, 1998: 130), student interviews allow the researcher to understand the meanings that everyday classroom activities hold for students (Marshall & Rossman, 2006: 102). In this accordance, following Patton (1980), Merriam affirms why a qualitative researcher should conduct an interview:

We interview people to find out from them those things we cannot directly observe… We cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that prelude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world—we have to ask people questions about those things. The purpose of interviewing, then, is to allow us to enter into the other person‟s perspective (1988: 72).

observe students‟ perceptions and attitudes about the teaching program. In other words, interview data validated observation data.

3.7 Data Analysis Methods

In the present study, data were analyzed on the basis of data collection methods. During data analysis, all the participants were mentioned pseudonymous to maintain their confidentiality (Burns, 2010; Stake, 2010; Dawson, 2009; Marshall & Rossman, 2006; Seidman, 2006; Dörnyei, 2003; Silverman, 1993).

In general, data were analyzed based on three phases of data transformation: description, analysis, and interpretation (Wolcott, 1994 as cited in Marshall & Rossman, 2006: 154). Following Strauss & Corbin (1997), Marshall & Rossman (2006: 154) argue that qualitative data analysis is a search for general statements about relationships and underlying themes in building grounded theory. Concerning the three phases of data transformation, Marshall & Rossman (2006: 154) specify that these three somewhat distinct activities are often bundled into the generic term analysis. In this case, following Walcott (1994), Marshall & Rossman state:

By no means do I suggest that the three categories—description, analysis, and interpretation—are mutually excusive. Nor are lines clearly drawn where the description ends and analysis begins, or where analysis becomes interpretation…. I do suggest that identifying and distinguishing among the three may serve a useful purpose, especially if the categories can be regarded as varying emphases that qualitative researchers employ to organize and present data (2006: 154).

Student written texts were analyzed in reference to the holistic scoring rubric for evaluating portfolios suggested by O‟Malley & Pierce (1996) as indicated in Chapter 2, Section 2.2.6. The holistic scoring rubric consists of four dimensions of writing measured in this study, namely idea development or organization, fluency or structure, word choice, and mechanics (O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996: 142) as already discussed in Chapter 2, Section 2.2.6. This selection was based on the consideration that the dimensions of writing in the rubric were workable for the present study. Regarding this, O‟Malley & Pierce state:

rationale for using a holistic scoring system is that the total quality of written text is more than the sum of its components. Writing is viewed as an integrated whole (1996: 142).

Classroom observation data were analyzed in the integration with the discussion of teaching program in Chapter 4. The data were used to support the implementation of the teaching program. Meanwhile, interview data analysis was undertaken in the form of coding or thematization (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007; Marshall & Rossman, 2006; Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003; Alwasilah, 2000). The analysis was directed to address the research questions through some steps. The first one was to put interview questions into categories. Then a categorization on the basis of respondent answers was developed to establish the recurring patterns or emerging regularities (Maxwell, 1996; Creswell, 1998; Alwasilah, 2000). In this connection, Cohen, Manion, & Morrison (2007: 368) propose several stages in interview analysis: (a) generating natural units of meaning, (b) classifying, categorizing, and ordering these units of meaning, (c) structuring narratives to describe the interview contents, and (d) interpreting the interview data.

Data from the structured questionnaire were analyzed using a frequency count or univariate analysis (Dawson, 2009: 127). The analysis was aimed to describe and present the aspects of personal empowerment addressed in the present study (Dawson, 2009: 127; Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007: 503). According to Dowson (2009: 127), frequency count is usually the first stage in any analysis of questionnaire, and it is fundamental for many other statistical techniques.

3.8 Conclusion

Chapter Four

The Teaching Program

4.1 Introduction

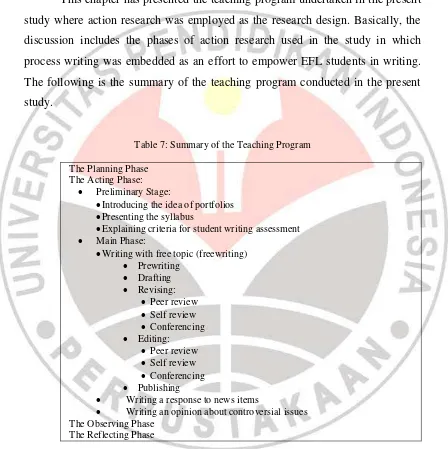

This chapter presents the phases of teaching program conducted in the present study. In general, the teaching program followed the phases of action research used in the present study, namely planning, acting, observing, and reflecting as indicated in Section 3.3 of Chapter 3. The planning phase was concerned with the data gained from the pilot study. It provided an analysis and reflection about the data. The acting phase consisted of two stages: preliminary and main stages. The preliminary stage involved introducing the idea of portfolios, presenting the syllabus to the class, and explaining the criteria for student writing assessment. The main stage concerned writing activities undertaken in the study, namely writing with free topic, writing a response to news items, and writing an opinion about controversial issues. All the activities in the acting phase involved planning, observing, and reflecting aspects to see the strengths and weaknesses to be considered for the next instructions. The observing phase concerned the evaluation about what worked and did not work in the teaching program. The reflecting phase was to do with researcher‟s reflection and evaluation about the overall program whether the program was successful or not.

4.2 The Planning Phase

writing course implemented in the research site originally quoted by the researcher:

Dalam perkuliahan writing selama ini, kami banyak diberikan tugas menulis pastinya. Tapi terkadang waktu yang diberikan sangat singkat sehingga kurang membuat saya fokus.

(In the current writing course, we are given a lot of assignments of writing of course. However, the time is so short sometimes that I cannot be focused)

Selama ini menulis hanya berdasar kebutuhan dan tidak berdasar kebebasan sehingga siswa agak enggan menulis dalam perkuliahan serta belum adanya penghargaan secara langsung dalam penulisan yang telah dilakukan.

(So far, writing is based on needs, not freedom, so students are less motivated in the course, and there has not been a direct appreciation to writing results)

Menurut saya, karena masalah topik yang selalu ditentukan oleh dosen membuat saya sangat minim dalam menulis. Karena tidak adanya kebebasan menulis dan kebebasan memilih topik yang disenangi dan dikuasai.

(To me, due to the topic always determined by the lecturer, I write very little. This is because I have no freedom to write and choose the topic I know and I am interested in)

Kayaknya sih penjelasan dosen kurang menarik jadinya susah dicerna. Kata-kata suka dibatasin, ngehambat kreativitas tuh.

(It seems that the lecturer‟s explanation is less interesting, so it is not easily understood. The words are often limited. That hinders creativity, you know)

Mendingan mahasiswa dikasih kebebasan dulu buat nulis, terus baru dikasih “rules”-nya. Kalo dikasih rules dulu, I have no idea to write down on paper.

(It would be better if students are given freedom to write, and then they are just provided with rules. If rules first, I have no idea to write down on paper)

4.3 The Acting Phase

The acting phase is the phase where students wrote a text. It consisted of two stages: preliminary and main stages. The preliminary stage involved introducing the idea of portfolios, presenting the syllabus, and explaining the criteria for student writing assessment. The main stage consisted of three writing activities, namely writing with a free topic (freewriting), writing a response to news items, and writing an opinion about controversial issues as already mentioned in Chapter 2, Section 2.4.3. These three types of writing were conducted through a process of writing including prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing as indicated in Chapter 2, Section 2.4.1.

4.3.1 The Preliminary Stage

Before asking students to write, the researcher did several activities preparing students for writing. First, he introduced the idea of portfolios to the class. Second, he presented the syllabus of the writing course. Third, the lecturer explained about the criteria of writing assessment produced in the teaching program.

4.3.1.1 Introducing the Idea of Portfolios

In order that students understood about the teaching program, the researcher introduced the idea of portfolios to the class. It was found out that students seemed to have not been familiar with portfolios. This can be seen from their answers related to the portfolio questions. For example, students did not answer appropriately the question concerning the definition of portfolios. Besides, they seemed to have no experience with reflective activities which is the key to portfolio-based instruction (O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996; Hamp-Lyons, 2006).

topics, namely 352 words for the second topic and 686 words for the third topic as will be discussed in Chapter 5. Lala stated:

The difficulties I had during the course occurred only in the beginning of the class. It might be caused that I had not understood the system of the class (what I meant here is the portfolio). I found it very difficult when I firstly got a writing task. Firstly, I got difficulties in idea development or organization. The idea I developed in every paragraph could only be written in not more than three supporting sentences. Secondly, the grammar I used was only limited to simple tense, not various. Beside that, there were still some grammatical mistakes I made. The last difficulty was concerned with word choices. My habit was that I always repeated the same words. It also happened in the conjunction usage. However, when I had to write for the next topics, I came to find it easy. I really caught the lecturer‟s point that I used the thesaurus to help write the essay rich of words. Here, I think I have found the solution of my problem [May 21, 2011].

To solve this problem, it was important to introduce the concept of portfolio to students in which they considered it as a new experience. This was also stated by the classroom observer who viewed portfolio-based instruction as a new culture for students. In facing the new culture, students had to deal with a new rituality, property, attitude, and social relations, particularly among students and the lecturer. The classroom observer noted:

During my observation on the instructional process implemented by the lecturer and his fifteen students, I can witness that writing is basically not just about a skill that can be separated from a culture. I mean that writing is so cultural that learning to write is to learn a new culture. In some early meetings, students seemed to be unaccustomed to some aspects of the new culture. Some of them looked surprised, and some others got enthusiastic. For example, when the lecturer introduced the way of scoring called portfolio assessment, the students expressed their astonishment upon multiple drafting with some feedback from peers or lecturers plus self-reflection from the writer. Such a surprise shows that they have not realized the importance of other‟s comments and self -reflection in the process of writing. Some students demonstrated their enthusiasm when they began to realize that portfolio approach is different from the traditional one. When they were told to be more independent and were more cooperative one another in producing a piece of writing in the course, they appeared to come to be glad and motivated. The students‟ surprise and enthusiasm is an important fact that combines pessimism and enthusiasm in facing a new situation, or, in this case, a new culture, that is writing culture with new demands of rituality, property, attitude, and social interactions among students and the lecturer [June 25, 2011].

This suggested the necessity of introducing the concept of portfolios to students. To follow Kemp & Toperoff (1998), the researcher started with the explanation of the etymology of the word „portfolio‟ from portare (carry) and foglio (sheet of paper). Even, according to Kemp & Toperoff, the teacher can ask

to students, there are several points to include: a portfolio definition, a rationale for using portfolios, a framework in the shape of a suggested contents list, checklists used for feedback, and ideas for themes and evidence. By so doing, students can understand what is actually meant by the concept of portfolios.

4.3.1.2 Presenting the Syllabus to the Class

After introducing the notion of portfolios to students, the researcher informed students with the syllabus of the writing course which was going to be used in the teaching program as indicated in Appendix 1. Regarding this, students were told about what topics to be written and how they had to do with the topics. In order that students understood the content of the syllabus, they were allowed to ask a question. Therefore, in this stage, there was a question and answer session between the lecturer and students.

4.3.1.3 Explaining Criteria for Student Writing Assessment

Before students were asked to write, they were told about the criteria of proficient text. This was to follow the suggestions that “students need to know how their work will be evaluated and by what standards their work will be judged” (O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996: 36). In this line, Gottlieb (2000: 91) explains that portfolios must have a specified purpose matched to defined targets with clear-cut criteria. With regard to the present study, students had to write a text by paying attention to the four dimensions of writing: idea development or organization, fluency or structure, word choice, and mechanics (O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996: 143) as indicated in Section 2.2.6 of Chapter 2.

4.4 The Main Phase

In this phase, students wrote three different texts. First, they wrote with free topic (freewriting). Second, they wrote a response to news items. Third, they wrote an opinion about controversial issues. These three texts were produced through the same stages of writing employed in the present study, namely prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing as already mentioned in Chapter 2, Section 2.4.1. In addition, in some stages of writing, particularly in revising and editing, students were asked to conduct peer or self review or assessment and conferencing to apply the principle of collaborative learning in portfolio-based instruction.

4.4.1 Writing with Free Topic (Freewriting)

In freewriting students were asked to write on the basis of their own topic. This was to apply the principle of portfolio-based instruction that students involve in decision making (O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996; Genesee & Upshur, 1996; Gottlieb, 2000). One of the activities in decision making is that students choose their own topic for their writing (see Graves, 1994: 42). Hence, there was not any intervention from the lecturer to students in freewriting. However, students could ask for an aid or consideration from their peers or lecturer if they needed it as suggested by Kroll (2003), Rao (2004), and Hamp-Lyons (2006). Because of free topic, students produced different types of texts. Of the fifteen students, eight of them wrote about argumentative writing, five students wrote about descriptive writing, and two students about narrative writing.

4.4.1.1 Prewriting

complete piece of paper. All these activities of planning were carried out in the classroom and follow the suggestions that students choose a topic, gather and organize ideas, and identify the purpose of writing before they write a draft (National Writing Project of America, 2006; Tompkins, 2008).

Regarding prewriting, Sharples (1999: 75) argues that a writing plan plays a role as “a mechanism for idea exploration and creative design”. In processing the design, according to Sharples, students should always revisit it and adapt it with the changing situation in order to produce a good piece of writing. In other words, the success and failure of a writing task can be determined in this stage. In this context, Sharples (see also Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005: 157-158) claims:

Making a writing plan organizes thoughts and guides the production of text. A plan needs to satisfy both of these purposes. If it is illogical and fails to organize ideas then it will not form the basis of a coherent argument. If it does not offer a coherent rhetorical structure, then the resulting text is likely to be shapeless and rambling….At the very least, time spent on planning is time well-spent. It gives an opportunity to reflect on the content and structure of the text, and this appears to pay dividends in improved quality (1999: 88-89).

The following are several testimonies of the importance of establishing prewriting in writing. These testimonies were taken from the reflective notes written immediately as soon as the course was over by the researcher during the teaching program:

…. A student asked about the possibility for topic change because he thought that the topic was too simple to develop. My answer is that he must not change the topic because so far the text produced has got some feedback from many people. This means that the text has been written through some processes. If he changes the topic, he must process the text from the beginning again, and that is not possible. He seemed to understand my explanation. I told him that if it is not possible anymore for him to develop the text on the idea aspect, he still may develop it on other aspects, such as grammar and vocabulary [October 1, 2010].

Generally, I can see that the students are enthusiastic enough and involved with their topic. Being involved here means that the students seemed to realize that planning in writing is important because it will determine the next writing processes. For example, the case that happened to Fredi and Agus deals with the planning of writing. Fredi said that the topic he wrote was too simple, so it could not be developed anymore. At the moment, he wrote about „Our Trip to Garut‟. According to Fredi, he could not develop his topic anymore, and Agus could not either. He thought that his writing about „Gold‟ was not too interesting and it was difficult to develop [October 27, 2010].

admits that planning is important for children to be able to deal with writing topics regardless of personal interests.

Pertinent to the whole writing process conducted in the present study, one of the students admitted that the way of teaching writing like in the teaching program should be implemented in every writing class. The student stated:

The way of writing class like this should be applied by every writing lecturer. The way of lecture like this helped me very much in developing ideas without being afraid to make mistake in grammar or other writing aspects.

Data above indicates that the writing stages conducted in the present study, in which prewriting is one of the stages, has played a role in increasing students‟ ability in developing ideas. Through prewriting, students were guided in generating ideas and developing their texts without being worried to make mistakes.

4.4.1.2 Drafting

As soon as students were finished with their writing framework, they were asked to develop it into a real piece of writing. This was done in the classroom around twenty minutes. To encourage students generate ideas, the lecturer reminded them not to worry about grammatical mistakes. This is relevant with the suggestions that in drafting students just pour out ideas and neglect mechanics (Tompkins, 2008: 12; Shield, 2010: 14). Tompkins (2008: 12-13) further explains that there are two main activities at this stage. First, students produce a rough draft. In this case, the emphasis is on content rather than mechanics (see also Dorn & Soffos, 2001: 33). Second, students make opening sentences or a composition‟s leads to grab readers‟ attention.

As part of the whole writing process, drafting has been considered as a not-once-time-finished product of writing. Instead, it involves multiple drafting (Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005; Harmer, 2004; Dorn & Soffos, 2001). Dorn & Soffos explain:

tool for organizing, reorganizing, and reflecting on the quality of their compositions. Thus, drafts can be numerous and messy (2001: 33).

Thus, in drafting, students were asked to express ideas as many as possible without paying too much attention on mechanical or grammatical errors. In this case, the objective is that students were able to state their thesis clearly and develop the content of their paper with sufficient specific details (Langan, 2001: 32). The weaknesses that occur in drafting will be revised in the next stage, namely the revising stage. Concerning the drafting, some students expressed that they were confident and motivated in writing because they were given freedom to develop ideas without having to be worried about mistakes (Rita, Anggi, Mira, Wati).

4.4.1.3 Revising

Basically, to follow the suggestions from Tompkins (2008: 13), in this stage, students “clarify and refine ideas” in order to build idea development. Students establish “substantive changes” (Tompkins, 2008: 7) or “macro editing” (National Writing Project of America, 2006: 26) rather than focus on minor changes of the paper. Concerning the present study, there were three important activities done in this stage: peer review, self review, and conferencing. These three activities were to apply the principle of portfolios that students should be collaborative to improve their writing. Concerning the present study, collaboration happened between student-student and student-lecturer.

4.4.1.3.1 Peer Review/Assessment

case, students discussed the strengths and weaknesses of their papers and suggest for improvement (Kern, 2000: 206).

Peer-assessment has been considered crucial in the writing process (Harmer, 2004; Hyland, 2003). From peer-assessment, students can move to independent self-assessment (O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996: 40). In view of the concern of this present study, as the key to the portfolios (Hamp-Lyons, 2006, 2003; O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996), self-assessment will lead students to personal empowerment (Montgomery & Wiley, 2004: 4; Gottlieb, 2000: 103).

Peer-assessment can take place in a number of forms and at various stages of the writing process (Hyland, 2003; Kern, 2000; Grabe & Kaplan, 1996). The most common way is that the teacher assigns students to work in pairs or small groups of tree or four to exchange drafts, read and give comments on one another‟s papers before they revise them (Hyland, 2003: 200; Kern, 2000: 207). According to Hyland (2003: 202), what makes peer-assessment important is that it can help students become more aware of their target readers when writing and revising. In addition, it can also help them become more sensitive to problems in their writing and more confident in correcting them.

Theoretical foundation for peer-assessment comes from the idea that knowledge develops through social interaction (Williams, 2005; Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005; Grabe & Kaplan, 1996). In this case, students are viewed as participants in a community of writers rather than as solitary writers (Williams, 2005: 93). Through self-assessment, students are encouraged to work collaboratively (Harmer, 2004: 115) and are supposed to develop linguistic knowledge and writing skills in a mutually supportive environment (Williams, 2005: 93).

Below are the participants‟ responses pertaining to peer-assessment undertaken during the teaching program:

Interactingwithfriends is an important part during the course. From their suggestions and comments, I realize that I have done many mistakes. This activity, I think, has played an important role to improve my quality of writing [Wati, March 31, 2011].

Sharing ideas can improve the content of the text we write, and, indirectly, it makes us know about the important ideas of the texts they write [Lala, March 28, 2011].

Data above show that peer-assessment has played a role in improving the quality of student writing. Through peer-assessment, students will get feedback from their peers about the advantages and disadvantages of their writing so that their writing improves.

4.4.1.3.2 Self Review/Assessment

In this stage, to follow the suggestions from Tompkins (2008: 13), students were asked to reread the rough draft. They were given an opportunity to reflect the strengths and weaknesses of their writing. The duration for this review was around five minutes. Students were given freedom to agree or disagree with the feedback from their friends. To this end, they were suggested that they consulted credible sources, such as books, dictionaries, and source persons.

As the core of portfolio-based learning approach (Hamp-Lyons, 2006, 2003; O‟Malley & Pierce, 1996), self-assessment plays a role for student empowerment (Montgomery & Wiley, 2004: 4; Gottlieb, 2000: 103). Through self-assessment, students make a review on the strengths and weaknesses of their work by developing their learning autonomy and responsibility (Williams, 2005: 161; Brown, 2004: 270). In this relation, Tompkins stipulates:

In self-assessment, children assume responsibility for assessing their own writing and for deciding which pieces of writing they will share with the teacher and classmates and place in their portfolios. This ability to reflect on one‟s own writing promotes organizational skills, self-reliance, independence, and creativity (2008: 84).

The following are the participants‟ responses in accordance with self -assessment or reflection they conducted during the teaching program:

I can correct and reread my own writing more carefully [Ambar, no date].

I can recognize that my writing is not perfect. There are still a lot of mistakes I did in every piece of my writing [Wati, March 31, 2011].

I can recognize my mistakes and realize what I have to do. I would like to make my writing better [Yuni, March 29, 2011].

I can improve my writing so that it is ready to correct by my friends [Lala, March 28, 2011].

Data above indicate that self-assessment has contributed to the improvement of student writing. In this way, students were given opportunities to reflect the strengths and weaknesses of their writing so that “their sense of authority grows” (Hirvela & Pierson, 2000: 109). Through the sense of authority or ownership, it is expected that students will be responsible to improve the quality of their writing.

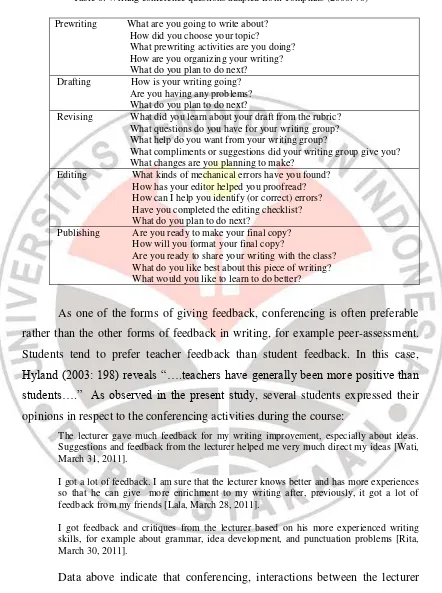

4.4.1.3.3 Conferencing

In this stage, to follow Tompkins (2008: 77), the lecturer approached students to discuss their writing at their desk by moving around the classroom. However, sometimes, the student was asked to come to the lecturer‟s desk for the discussion. In this conferencing, the lecturer conducted a conversation or dialogue with the student to find out how he or she would improve the paper (Tompkins, 2008; Brown, 2004; Hyland, 2003; Genesee & Upshur, 1996). In this case, the lecturer positioned himself as a facilitator and guide as suggested by Tompkins (2008: 77) and Brown (2004: 265).