www.elsevier.com/locate/econedurev

Post-school-age training among women: training methods

and labor market outcomes at older ages

Elizabeth T. Hill

*Penn State Mont Alto, Campus Drive, Mont Alto, PA 17237, USA

Received 1 July 1997; accepted 1 July 1999

Abstract

This study uses the NLS Mature Women’s Cohort to examine labor market effects of education and training on women at pre-retirement ages, comparing training methods: formal education, on-the-job training, and other training. Results show that younger, more educated women tend to train more than other women and that some women appear in a ‘training track’. While both education and on-the-job training are associated with higher wage levels, on-the-job training is most strongly associated with wage growth. Women who acquire training as adults tend to work at older ages. 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

JEL classification: J2; J3

Keywords: Human capital; Salary wage differentials; Economic impact; Productivity

1. Introduction

The majority of the population over age 55 living in poverty have been identified as unmarried women who are not employed (Sandell, 1987). Because women’s earnings and labor force participation are lower than men’s, their retirement income is also typically lower. This situation may be worsened by attempts to reform the social security system.

Although most people rise above the poverty level through wage income, this avenue may close to older women. According to human capital theory, age–earn-ings profiles, which rise with human capital at younger ages, flatten out as workers become older and may even fall due to depreciation and obsolescence of human capi-tal (Becker, 1975; Mincer, 1993). If women enhance their skills through education or training, their sub-sequent income would likely rise, thereby reducing their probability of entering the class of elderly poor. But to

* Tel.:+1-717-749-6221; fax:+1-717-749-6069. E-mail address: [email protected] (E.T. Hill).

0272-7757/01/$ - see front matter2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 2 7 2 - 7 7 5 7 ( 9 9 ) 0 0 0 5 9 - X

what extent does adult education and training cause older women’s earnings to continue to rise? Among recent studies of training, none seems to have focused on older women, and few have included them.

Several studies reveal women’s training disadvantage compared to men. These indicate that women are often placed into jobs where less training is provided, presum-ably because of their lower labor force attachment (Royalty, 1996; Loewenstein & Spletzer, 1994; Barron, Black & Loewenstein, 1993). While this study does not compare men and women, it does find a wage advantage for women who train at older ages over those who do not train.

Although many women obtain training after the usual schooling age and government training programs exist to promote women’s training, studies have not compared training methods and subsequent labor market benefits for older women. Government training programs such as the Job Training Partnership Act and the Displaced Homemaker Program, which have attempted to help off-set women’s labor market disadvantage, have not focused on one training method. Some grant aid for women to further their education. Others provide incen-tives to employers for hiring and training women, thus providing both on-the-job training and work experience. But if one method of training provides a greater labor market benefit than others, increased government aid for the more beneficial training is desirable. If one training method: classroom, on-the-job, or off-the-job training, results in greater wage increases, that information would also help women make better training decisions. This study finds that on-the-job training appears to provide the greatest wage advantage.1

The person making the training decision differs some-what according to the type of training. Employers decide, at least partly, who receives on-the-job training while workers themselves make more decisions about edu-cation and other training programs. Determining the characteristics of women who receive on-the-job training will provide insight into the types of women employers choose to train. If the access of older women to on-the-job training is blocked because of a shorter investment return period, this type of training will not help solve their problems.

Results show that women can improve their wages with training even at older ages. But to obtain on-the-job training—which raises wages most—it appears necessary that women show employers that their training expenditures will pay off. Loewenstein and Spletzer’s (1994) observation that employers delay substantial training in women appears to support this notion. Women with early labor force attachment and additional work experience obtain more training at work. And both work experience and on-the-job training are associated with wage increases and labor force participation at older ages.

This study finds that other factors may offset the

train-1 According to traditional human capital theory, workers pay for general training either directly or through reduced wages if training is provided by employers, while the firm and the employee share the cost of specific training. For recent training, reduced wages to compensate for training might render the effect of training on wages inconclusive. However, this analysis uses the data when respondents had reached ages 47–61. The data provide training information over a number of years so that any time of reduced wages to pay for training is likely past for most training episodes, and many of the resultant changes in productivity and wages have already taken place.

ing disadvantage of older women. Better-educated women train more, a finding similar to that of Lillard and Tan (1992). Some women move into a training track. The results indicate that later education is not significant with regard to wage increases for older women, a result which differs from Lynch (1992) who found that edu-cation results in a wage change advantage for younger women.

2. Data

The National Longitudinal Survey of Labor Market Experience for Mature Women which began in 1967, interviewed women for the first time when they ranged from 30 to 44 years of age. This study focuses on the period up to 1984 when the women reached ages 47 to 61 because that was the last year before this cohort began eligibility for social security retirement benefits and/or pensions, no doubt changing their labor market incen-tives.

The NLS Mature Women’s Cohort contains 5083 women, In order to select women for whom 1984 infor-mation was available, only women who responded to the survey that year are included, producing a sample of 3422 cases. Wage data for many of the survey years are available so that wage changes can be measured.2

The survey asked whether respondents had obtained post-school-age education and training in the first wave of the survey, in several subsequent waves, and on the 1984 survey by which time, 2127 (62%) of the women reported training after the usual schooling age.3Because

this is panel data, training questions could be asked soon after relevant time periods, probably resulting in more accurate recollections. Also, the initial (pre-1967)

train-2 Information about age, race, 1967 educational level, mari-tal history, and 1984 region of residence were available for all of those cases; years employed, for 90% of them. Wage data were available for about half of the 1984 respondents and asset data, for 73%. Comparing women interviewed in 1984 with the total original sample in terms of having taken training prior to 1967 reveals differences of 0.2 percentage points or less so that attrition does not appear related to training during early post-school years. For other 1967 characteristics, the percentage dif-ferences were 1% (race—fewer non-whites in 1984) or less than 1% (age, educational level, years work experience).

Obtained before Responding in Entire NLS Mature 1967 1984 (N=3422) Women’s cohort

(N=5083) Education 15.3% (525) 15.1% (770) On-the-job training 9.2% (314) 9.3% (474) Other training 23.9% (818) 23.8% (1210)

ing data can be controlled for separately. Although the education and training questions were asked separately by method only in 1967 and for the period covering 1977–1984, the majority (55%) of the respondents reported the acquisition of education, on-the-job training, and other (technical, commercial, or skill) training. Infor-mation about all levels of education was available from 1967 to 1977 but only college from 1979 to 1984. This study analyzes reports of at least one occurrence of a type of training rather than the duration of training.4

Despite their crudeness, these measures provide some insight into the training of older women (see Appendix A).

3. Method of training—total sample and by occupation

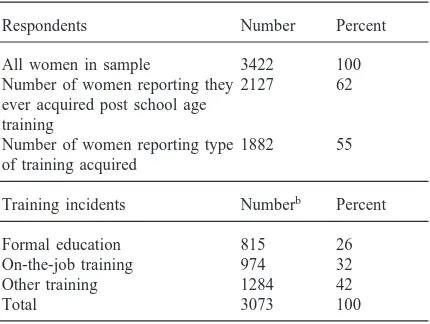

A breakdown of the training incidents in Table 1 shows that 1882 women or 55%, reported their training method by 1984. Because many had trained by more than one method, the number of training incidents was 3073. A woman was included once for each method of training she reported. In about one-fourth of the incidents

Table 1

Training acquired after the usual schooling agea

Respondents Number Percent

All women in sample 3422 100

Number of women reporting they 2127 62 ever acquired post school age

training

Number of women reporting type 1882 55 of training acquired

Training incidents Numberb Percent

Formal education 815 26

On-the-job training 974 32

Other training 1284 42

Total 3073 100

a Includes post-school-age training before 1967 as well as survey years (1967–1984).

b Respondents could be included in more than one group but only once for each training method.

4 Using variables for the time spent training by each method which was surveyed between 1979 and 1981, rather than the acquisition of training by that method, substantially reduced the number of cases and provided little information except to show a positive correlation between time spent in college and in on-the-job training. Veum (1995) reports that it is the incidence rather than the duration of training which is positively associa-ted with the wage level.

respondents acquired formal education; in about one-third, on-the-job training. The respondents classified over two-fifths of the incidents as ‘other’ training, defined as neither formal education nor on-the-job training.

Because the skills needed in various occupations dif-fer, training methods might also differ by occupation. Table 2 reports training methods by occupation. The last column indicates that on average, more than two training methods (2.28) were experienced by women in pro-fessional and technical occupations who received train-ing. The average number of training incidents appears to fall along with the skill level of the occupations. How-ever, Table 2 reveals that the average number of inci-dents for all occupations is 1.63. Apparently, women who train often train by more than one method.

Table 2 also shows the percentage of the incidents for each occupation by training method. Although education was not used most often for any of the occupations, women in professional/technical and craftsmen/foremen, occupations requiring a high degree of skill, trained at least 30% of the time by that method. Sales workers, managers/proprietors, operatives, and clerical workers trained in formal classes in 24% or more of their train-ing episodes.

On-the-job training was used in 30% or more of the training events for all of the occupations except farmers and farm workers.5Not surprisingly, managers and

pro-prietors, likely to need more training specific to the firm than other occupations, reported a larger percentage (39) of their training as on-the-job training incidents.6

In more highly-skilled occupations, education and on-the-job training were typically used to train workers while workers in less-skilled occupations tended to acquire other training. Although not a direct comparison, the large percentage of other training for all of the occu-pations tends to support previous studies observing that women acquire more off-the-job training than men (Loewenstein & Spletzer, 1994; Veum, 1993; Lynch, 1991).

4. Who receives training?

The decision to train may be made jointly between a woman and her employer or by the woman alone. In either case, women likely differ according to their

Table 2

Method of training by occupationa

Occupation Education On-the-job Other training Total Number Average

incidents respondentsb number of incidentsc

Nd (%)e N (%) N (%)

Prof. technical 223 (34) 236 (35) 208 (31) 667 293 2.28

Mgrs., propriet. 58 (25) 89 (39) 83 (36) 230 130 1.77

Clerical 175 (24) 266 (37) 286 (39) 727 446 1.63

Sales 38 (26) 45 (31) 64 (43) 147 85 1.73

Crafts.foremen 16 (30) 16 (30) 21 (40) 53 33 1.61

Operatives 32 (25) 45 (36) 50 (39) 127 90 1.41

Service 68 (18) 122 (32) 186 (50) 376 257 1.46

Farmers 3 (19) 3 (19) 10 (62) 16 10 1.60

Farm workers 1 (14) 1 (14) 5 (72) 7 5 1.40

Non-farm, non-mine laborers 1 (12) 4 (44) 4 (44) 9 8 1.13

Not reported 200 (28) 147 (21) 367 (51) 714 525 1.36

Total 815 (26) 974 (32) 1284 (42) 3073 1882 1.63

a Current or most recent occupation of respondent in 1984. b Includes only women who reported type of training received.

c Total incidents by all methods/total respondents in occupation reporting type of training received.

d Number of incidents. Each method counted only once resulting in a maximum of three incidents per respondent. e Percent of total incidents for that occupation.

characteristics in the acquisition of training. For example, older women might train less than younger women because both the women and their employers perceive a shorter return time on their training invest-ment. If discrimination exists, white women might receive more on-the-job training or, if equal opportunity legislation has a strong effect, they might receive less. Marital history, educational level, and work experience

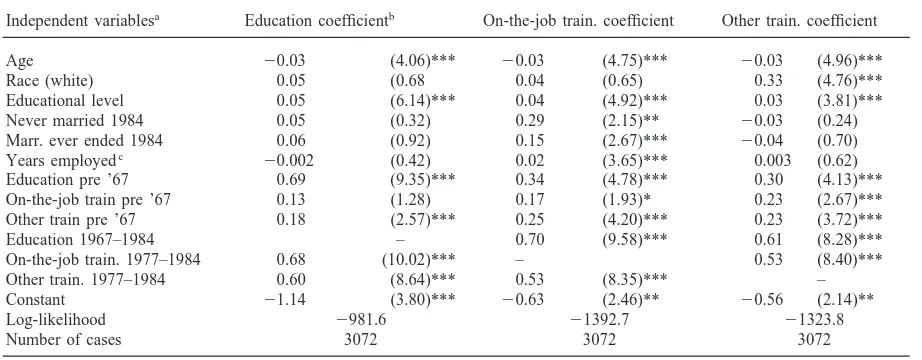

Table 3

Characteristics associated with acquiring education and training during the survey years (1967–1984)

Independent variablesa Education coefficientb On-the-job train. coefficient Other train. coefficient

Age 20.03 (4.06)*** 20.03 (4.75)*** 20.03 (4.96)***

Race (white) 0.05 (0.68 0.04 (0.65) 0.33 (4.76)***

Educational level 0.05 (6.14)*** 0.04 (4.92)*** 0.03 (3.81)***

Never married 1984 0.05 (0.32) 0.29 (2.15)** 20.03 (0.24)

Marr. ever ended 1984 0.06 (0.92) 0.15 (2.67)*** 20.04 (0.70)

Years employedc

20.002 (0.42) 0.02 (3.65)*** 0.003 (0.62)

Education pre ’67 0.69 (9.35)*** 0.34 (4.78)*** 0.30 (4.13)***

On-the-job train pre ’67 0.13 (1.28) 0.17 (1.93)* 0.23 (2.67)***

Other train pre ’67 0.18 (2.57)*** 0.25 (4.20)*** 0.23 (3.72)***

Education 1967–1984 – 0.70 (9.58)*** 0.61 (8.28)***

On-the-job train. 1977–1984 0.68 (10.02)*** – 0.53 (8.40)***

Other train. 1977–1984 0.60 (8.64)*** 0.53 (8.35)*** –

Constant 21.14 (3.80)*** 20.63 (2.46)** 20.56 (2.14)**

Log-likelihood 2981.6 21392.7 21323.8

Number of cases 3072 3072 3072

a All independent variables as of 1967 unless otherwise indicated.

b Absolute value of t statistics in parentheses, significance level ***0.01, **0.05, *0.10. c At least 6 months and 35 h/week since age 18.

may also affect the post-school-age training decision because of anticipated labor force participation, training cost, and the need for updated skills. Table 3 reports the results of a probit analysis of the respondents’ character-istics to determine what differences exist among women who train by various methods.

obtained less training by any method, perhaps because they (or their employers) would have less time to reap the benefits of such investment in human capital. Or, controlling for years worked, older workers may work a smaller fraction of the time (are less serious about careers).

White women were more likely to acquire other train-ing but no more likely to acquire education or on-the-job training. Racial discrimination apparently did not affect training opportunities for nonwhite women, at least for the training methods where employers might have input into the training decision.

Loewenstein and Spletzer (1994) noted that women’s training was more likely to be delayed. It appears from these data that employers train women with a higher probable payoff: those whose marital status and work history indicate stronger labor force attachment. Women who were not married, at least at some time during the survey period, tended to obtain on-the-job training but not more education or other training than other women. Unmarried women who handle family responsibilities alone have a strong incentive to train but finding time

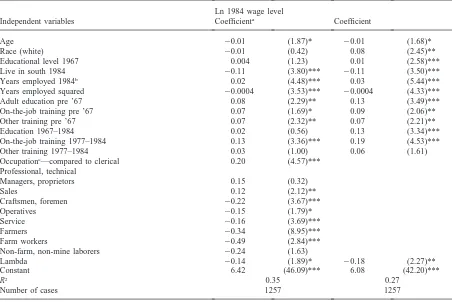

Table 4

Determinants of 1984 wage level

Ln 1984 wage level

Independent variables Coefficienta Coefficient

Age 20.01 (1.87)* 20.01 (1.68)*

Race (white) 20.01 (0.42) 0.08 (2.45)**

Educational level 1967 0.004 (1.23) 0.01 (2.58)***

Live in south 1984 20.11 (3.80)*** 20.11 (3.50)***

Years employed 1984b 0.02 (4.48)*** 0.03 (5.44)***

Years employed squared 20.0004 (3.53)*** 20.0004 (4.33)***

Adult education pre ’67 0.08 (2.29)** 0.13 (3.49)***

On-the-job training pre ’67 0.07 (1.69)* 0.09 (2.06)**

Other training pre ’67 0.07 (2.32)** 0.07 (2.21)**

Education 1967–1984 0.02 (0.56) 0.13 (3.34)***

On-the-job training 1977–1984 0.13 (3.36)*** 0.19 (4.53)***

Other training 1977–1984 0.03 (1.00) 0.06 (1.61)

Occupationc—compared to clerical 0.20 (4.57)***

Professional, technical

Managers, proprietors 0.15 (0.32)

Sales 0.12 (2.12)**

Craftsmen, foremen 20.22 (3.67)***

Operatives 20.15 (1.79)*

Service 20.16 (3.69)***

Farmers 20.34 (8.95)***

Farm workers 20.49 (2.84)***

Non-farm, non-mine laborers 20.24 (1.63)

Lambda 20.14 (1.89)* 20.18 (2.27)**

Constant 6.42 (46.09)*** 6.08 (42.20)***

R2 0.35 0.27

Number of cases 1257 1257

a Absolute value of t statistics in parentheses, significance level:***0.01, **0.05, *0.10*. b At least 6 months and 35 h/week since age 18.

c Occupation on current or last job.

outside work time may be difficult. Therefore, they may focus on acquiring on-the-job training. This variable may also measure a signal these women send to employers or employers’ perceptions about their labor force attach-ment.

training and educational level. But because the data used in this study measure fewer women at lower educational levels (see Appendix A), the data report less remedial education.

Further evidence of employers’ needs to observe a labor market commitment is provided by the finding that a strong early labor force attachment is associated with on-the-job training later in life but not with education or other training. Women with more work experience had strong incentives as well as increased opportunities for on-the-job training compared to those in the labor force fewer years. Although this analysis uses work experience rather than tenure with the firm, the positive statistically significant association of work experience with on-the-job training may also be due to the tendency of firms to train workers after they have been with the company for some time noted by other studies (Loewenstein & Spletzer, 1997; Barron et al., 1993; Lillard & Tan, 1992). Apparently certain women tend toward training. Women who acquired education and training after the usual schooling age but before 1967 more likely trained during the survey period.7Those who obtained education

and other training prior to 1967 acquired more training by all training methods from 1967 to 1984. Women who trained on-the-job prior to 1967 subsequently acquired more of both on-the-job and other training. That training in an earlier time period raises the probability of training later on is similar to the finding of Loewenstein and Spletzer (1994).

Table 3 shows that during the survey years, the methods of training appear to be complements rather than substitutes: women who received training by each method were more likely to obtain it by the other two methods. Some employees may signal employers that firms can benefit from training them. Alternatively or in addition, certain workers may be more interested in acquiring education and training.

5. Training and wages

If education and training are human capital invest-ments made to enhance productivity and productivity is reflected in wages, analyzing training and wages will show which training method enhances wages most. Table 4 shows the determinants of the respondents’ wages at older ages. The dependent variable, the log of the 1984 wage level, is presented with and without the 1984 or most recent occupation. It includes the 1967 educational level because education acquired after 1967 is a training variable. The Heckman (1979) selectivity

7 Measuring the effect of training reported in 1967 is difficult because the training could have occurred in 1967 or more than 25 years before that.

model controls for the fact that not all women worked and had a wage in 1984.8

Younger women, those with more work experience, and women who lived outside the south experienced higher wages than other women. Wages differed by occupation: women in professional/technical occupations and in sales experienced higher wages compared to women in clerical occupations while several of the other occupations showed significantly lower wage levels. All types of training obtained at early ages (before 1967) were associated with higher 1984 wage levels.

Concerning education and training during the survey period, when occupations were included, only those who received on-the-job training from 1977 to 1984 showed higher wages. However, when occupations were omitted, wage level advantages at older ages occurred from both education and on-the-job training. The benefit from adult education seems to occur by placing women into better-paying occupations.

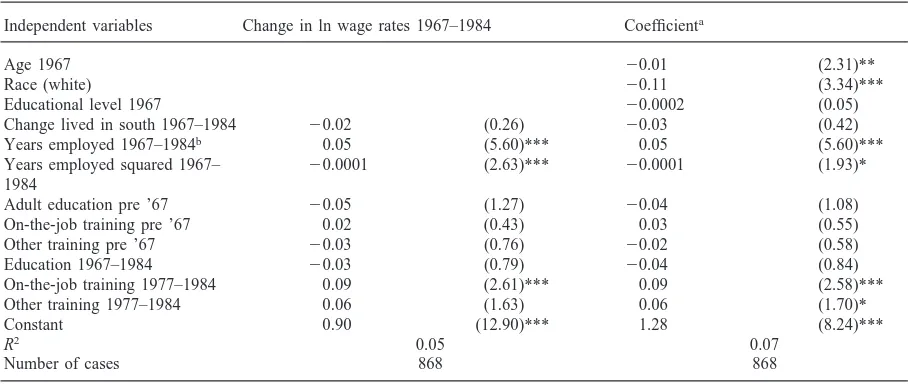

But older women need to find the path to greater wage growth. Table 5 analyzes wage increases during the sur-vey period using the change in the log of the hourly wage rate as the dependent variable. Using the variables from Table 4 which could change as well as 1967 training variables, the first wage specification in Table 5 indicates that working more years was associated with wage increases. This could be due to increased work experi-ence or to informal on-the-job training. Of the three training methods, on-the-job training programs showed

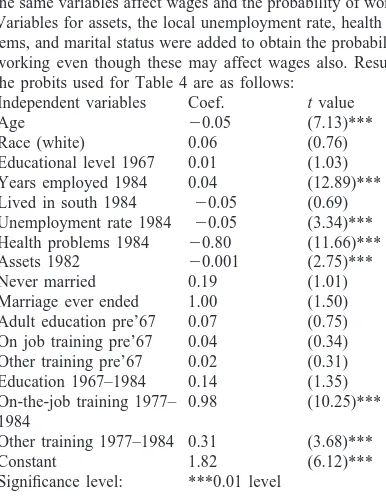

8 Identifying selection corrections is a problem because often the same variables affect wages and the probability of working. Variables for assets, the local unemployment rate, health prob-lems, and marital status were added to obtain the probability of working even though these may affect wages also. Results of the probits used for Table 4 are as follows:

Independent variables Coef. t value

Age 20.05 (7.13)***

Race (white) 0.06 (0.76)

Educational level 1967 0.01 (1.03) Years employed 1984 0.04 (12.89)*** Lived in south 1984 20.05 (0.69)

Unemployment rate 1984 20.05 (3.34)***

Health problems 1984 20.80 (11.66)***

Assets 1982 20.001 (2.75)***

Never married 0.19 (1.01)

Marriage ever ended 1.00 (1.50) Adult education pre’67 0.07 (0.75) On job training pre’67 0.04 (0.34) Other training pre’67 0.02 (0.31) Education 1967–1984 0.14 (1.35) On-the-job training 1977– 0.98 (10.25)*** 1984

Other training 1977–1984 0.31 (3.68)***

Constant 1.82 (6.12)***

Table 5

Determinants of wage changes 1967–1984

Independent variables Change in ln wage rates 1967–1984 Coefficienta

Age 1967 20.01 (2.31)**

Race (white) 20.11 (3.34)***

Educational level 1967 20.0002 (0.05)

Change lived in south 1967–1984 20.02 (0.26) 20.03 (0.42)

Years employed 1967–1984b 0.05 (5.60)*** 0.05 (5.60)***

Years employed squared 1967– 20.0001 (2.63)*** 20.0001 (1.93)*

1984

Adult education pre ’67 20.05 (1.27) 20.04 (1.08)

On-the-job training pre ’67 0.02 (0.43) 0.03 (0.55)

Other training pre ’67 20.03 (0.76) 20.02 (0.58)

Education 1967–1984 20.03 (0.79) 20.04 (0.84)

On-the-job training 1977–1984 0.09 (2.61)*** 0.09 (2.58)***

Other training 1977–1984 0.06 (1.63) 0.06 (1.70)*

Constant 0.90 (12.90)*** 1.28 (8.24)***

R2 0.05 0.07

Number of cases 868 868

a Absolute value of t statistics in parentheses, significance level: ***0.01, **0.05, *0.10. b At least 6 months and 35 h.

the strongest association with wage growth. The acqui-sition of later education was not associated with increased wages while off-the-job training was mar-ginally significant.9

The second wage equation in Table 5 includes several additional variables which might affect wage changes. Age and race might affect wage growth if age and race discrimination exist. Age, which might also include atti-tude or other factors affecting productivity, was negative and significant.

Non-white women had more wage growth than white women. However controlling for occupation, they had similar wage levels by 1984 (Table 4) so that older non-white women were apparently ‘catching up’ during this period. Educational level in 1967 was not significant, probably because better-educated women were paid higher starting wages.

Additional analyses using wage observations available for most of the survey years between 1967 and 1984 including education and training reported in 1967 showed no pattern and few significant training variables. The training identified as occurring between 1977 and 1984 displayed no clear pattern with regard to wage changes for each wave of the survey during that time although there is some indication that on-the-job training

9 Splitting education into that acquired before 1977 (all edu-cation levels) and college (the 1977–1984 measure) provided no advantage nor did using each wave of the education and training responses separately for wage changes between 1977 and 1984.

affected wages immediately while college enhanced wages with a delay.10

Whether those who receive training are those who would benefit most is difficult to tell since the selection process into training is unknown. Work experience may include the effect of informal on-the-job training which was not surveyed directly.

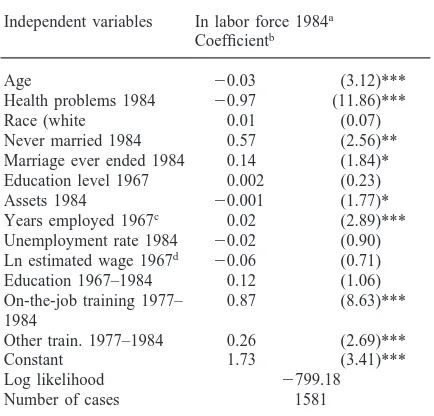

6. Training and labor force participation

If older women can alleviate their poverty through work, the analysis should focus on factors affecting labor force participation at older ages. Table 6 presents results of a probit analysis using labor force participation in 1984 to measure which women continued to work at later ages. Not surprisingly, older women and those with health problems tended away from labor force partici-pation. The need for income apparently provided an incentive to work at later ages: unmarried women and women with fewer assets tended toward market work. Early strong labor force attachment as measured by years employed full time in 1967, was associated with working

Table 6

Determinants of 1984 labor force participation

Independent variables In labor force 1984a Coefficientb

Age 20.03 (3.12)***

Health problems 1984 20.97 (11.86)***

Race (white 0.01 (0.07)

Never married 1984 0.57 (2.56)** Marriage ever ended 1984 0.14 (1.84)* Education level 1967 0.002 (0.23)

Assets 1984 20.001 (1.77)*

Years employed 1967c 0.02 (2.89)*** Unemployment rate 1984 20.02 (0.90)

Ln estimated wage 1967d

20.06 (0.71)

Education 1967–1984 0.12 (1.06) On-the-job training 1977– 0.87 (8.63)*** 1984

Other train. 1977–1984 0.26 (2.69)***

Constant 1.73 (3.41)***

Log likelihood 2799.18

Number of cases 1581

a Employed or unemployed 1984=1.

b Absolute value of t statistics in parentheses, significance level:***0.01, **0.05, *0.10.

c At least 6 months and 35 h/week since age 18.

d The estimated wage in 1967 was the 1967 wage if one was available. If the first available wage was for 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, or 1972, that wage was indexed using Wt=average hourly earnings in year t/average hourly earnings in 1967.

in 1984. The acquisition of both on-the-job and other training was associated with employment while obtaining education later was not. Perhaps taking classes was a substitute for working in the use of these older women’s time.11

7. Conclusion

This paper analyzes the labor market effects of train-ing for older women, a somewhat neglected segment of the population, many of whom have economic problems. These workers often encounter multiple labor market disadvantages and the resultant low incomes.

The majority of the women in the sample had obtained post-school-age training, a substantial number acquiring training by each of the three methods: education, on-the-job training, and other training (Table 1). Women in the more highly-skilled occupations commonly acquired training by more than one training method (Table 2), but all training methods were used for all of the occupations.

11 When variables for the 1967 log wage and the three types of training were replaced with a predicted 1984 wage, that vari-able was positive and significant at the 0.01 level.

Compared to other occupations, respondents in professional/technical and crafts occupations acquired more education while managers, clerical workers, and operatives received more on-the-job training. Women in less-skilled occupations tended to obtain training other than education and on-the-job training, appearing to con-firm the findings of other studies (Loewenstein & Spletzer, 1994; Veum, 1993) that less-skilled women are more likely to seek training on their own.

Employers appear to consider the return on their investment when deciding who to train, at least for on-the-job training courses. Younger women and those with a greater early labor market commitment received more on-the-job training (Table 3). Some women seem to place into a training track. Different forms of human capital appeared as complements rather than substitutes. Respondents with higher 1967 educational levels and women who obtained post-school-age education and training before 1967 trained more by all methods between 1967 and 1984. And those who trained by one method during the survey period also tended to train by other methods.

Although most other studies have not focused on older women, they have generally agreed on the comp-lementarity of post-school training and original edu-cational level as well as the positive effect of training on wages. Lillard and Tan (1992), analyzing the CPS, obtained such results. Lynch (1992), examining NLS Youth, found that schooling raised the probability of acquiring off-the-job training and apprenticeships although it showed little effect on receiving on-the-job training for men and women.

Education and on-the-job training were associated with higher wage levels, education working through placement into higher-paying occupations (Table 4). On-the-job training was most strongly associated with wage increases (Table 5). Barnow (1987) found similar results in a study of CETA recipients of all ages.

The acquisition of both on-the-job and other training as adults was associated with labor force participation by the women at older ages while obtaining education was not (Table 6).

The positive association between on-the-job training and wages agrees with Lynch (1992), who concluded that on-the-job training had a large effect on wages. That later education is not associated with wage increases dif-fers from Lynch’s findings for a younger cohort.

Table 7

Training measures and incidence

Data set Description Training measures Training incidence (% of

workers)

NLSHS72 (1986 wave) Employer-provided training On-the-job training; off premises 46 overalla training

9 tuition 28 formal 20 informal 20 off premises NLSY (1986–1991) Variable survey periods Training programs or on-the-job 38 any trainingb

training designed to help find a job, improve job skills or learn a new job

8 business, vocational, technical and correspondence courses 24 company training 5 other training

NLS young men (1967–1980) Variable survey periods Longest training event between 24–30 any trainingcregular or

interviews technical

4–5 school 8–10 company 9 other

NLS older men (1967–1981) Variable survey periods Longest training event between 10–17 any trainingc interviews

1 technical school 3–6 company 6–11 other CPS (1983–1991) All workers—cross-section Training ever received on-the-job 36–42 overalld

to improve skills

12–13 schooling 12–17 formal skills 15–16 informal

EOPP Employer survey—last hire Hours spent training during first 87 informaleby supervisors 3 months after hire

61 by coworkers PSID (1976) Within current job Amount of training needed until 29–76 any trainingf

the worker is fully trained

a Antonji and Spletzer (1991) p. 77. b Veum (1993) p. 29.

c Lillard and Tan (1992) p. 8. d Bishop (1997) p. 22.

e Loewenstein and Spletzer (1994) Table [1]. f Mincer (1991) p. 28.

The results suggest that programs to help older women should emphasize incentives for women to train and remain committed to the labor force so that they can prove themselves to their employers. Programs should also emphasize incentives to employers to provide on-the-job training for older women.12

12 Veum (1995) makes a similar recommendation for younger workers.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Charles Brown for many helpful comments and suggestions.

Appendix A

sought differs with various data sets, which often meas-ure different demographic groups (see Training measmeas-ures and incidence table, Table 7.

On-the-job training can be surveyed in a variety of ways. The NLS class of 72 data, for example, ask about both formal and informal training provided by the employer, while the Current Population Survey approaches formal and informal training by asking work-ers how long it took until they were fully trained to do the job and how they achieved that status. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics focuses on how long until a worker is fully trained while the Employment Opport-unity Pilot Project surveys employers about the training of new hires during their first three months.

The NLS Mature Women’s cohort, the other original NLS Cohorts and the NLS Youth data inquired about ‘on-the-job training courses’. The wording of the ques-tions implies formal on-the-job training so that informal training is likely understated or excluded. The 1979– 1984 Mature Women’s Survey asks ‘Since (previous interview date) have you taken any on-the-job training courses?’ so that all training since the last interview is included. A number of measures (CPS, EOPP, NLSHS72) inquire only about training from the current employer or training the respondent is currently receiv-ing. Therefore, the data used in this study cover a longer period and may come from more than one employer.

Between 1979 and 1984 the NLS Mature Women’s Cohort contains a broader measure of ‘other training’ than other data sets examined although the wording seems to exclude informal training. It inquires ‘Since (last interview date) have you taken any other training or educational programs other than on-the-job or college courses?’. The ‘other’ category, for example in the NLS Youth data, lists only certain types of training or places where that training might take place.

The wording of the questions in the NLS Mature Women’s Cohort was somewhat different in 1967 than later: ‘Since you stopped going to school full time, have you taken any additional courses such as English, math, science, or art?’ (used in this study as pre ’67 education); ‘Aside from regular schooling did you ever take a full time program lasting two or more weeks at a company training school?’ (pre ’67 on-the-job training); ‘Aside from regular school did you ever take any technical, commercial or skill training not counting on-the-job training given informally?’ (pre ’67 other training).

A 1977 question asking when they were last in school, identified those who acquired education from 1968 to 1977, but the survey did not identify women who received on-the-job and other training from 1968 to 1977. After 1977 separate questions asked types of train-ing, but the education question asked ‘Have you attended college since (last interview date)?’ identifying only col-lege courses.

The women placed in the ‘acquired education’

cate-gory if they stated they had attended college 1977–1984, or if they stated in 1977 that their last year in school was 1968–1977 and into the ‘acquired on-the-job training’ or ‘acquired other training’ groups if they stated they had received such training in 1979 (inquiring about training since the 1977 interview date), 1981, 1982, or 1984. The data probably understate the effects of education and training because education includes only college level education between 1979 and 1984, and the survey did not ask training questions separately by method between 1967 and 1977. The comparison group gave a negative response or no response.

A more general group of women who acquired an unidentified type of education or training between 1969 and 1977, was comprised of women who responded affirmatively to the broader education/training question in 1967, 1969, 1971, 1972, 1977, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1984 or who stated that their level of education was higher in 1977 than in 1967.

Questions which asked where respondents took the training (for example, company training school, college, vocational school) and whether the training was pro-fessional, managerial, clerical, etc., proved not to provide good information for this analysis.

References

Antonji, J. G., & Spletzer, J. R. (1991). Worker characteristics, job characteristics, and the receipt of on-the-job training. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 45 (1), 58–79. Barnow, B. S. (1987). Impact of CETA on earnings. Journal

of Human Resources, 22 (2), 157–193.

Barron, J. M., Black, D. A., & Loewenstein, M. A. (1993). Gender differences in training, capital, and wages. Journal of Human Resources, 28 (2), 343–364.

Becker, G. S. (1975). Human capital. (2nd ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bishop, J. H. (1997). What we know about employer-provided training. In S. L. Polachek (ed.), Research in labor econom-ics 16 (pp. 19–87). Greenwich, CN: JAI Press Inc. Brown, C. C. (1989). Empirical evidence on private training.

Investing in people 1. Washington, DC: Washington Com-mission on Workforce Quality and Labor Market Efficiency. Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification

error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161.

Lillard, L. A., & Tan, H. W. (1992). Private sector training: who gets it and what are its effects. In R. G. Ehrenberg (ed.), Research in labor economics 13 (pp. 1–62). Greenwich, CN: JAI Press Inc.

Loewenstein, M.A., & Spletzer, J.R. (1994). Informal training: a review of existing data and some new evidence. National Longitudinal Surveys discussion paper, report: NLS 94-20. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Loewenstein, M. A., & Spletzer, J. R. (1997). Delayed formal

on-the-job training. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 51 (1), 82–99.

of young workers. National Longitudinal Surveys discussion paper, report: NLS 92-8. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Lynch, L. M. (1992). Private-sector training and the earnings of young workers. American Economic Review, 82 (1), 299–312.

Mincer, J. (1991). Job training: costs, returns, and wage profiles. In D. Stern, & J. Ritzen, Market failure in training (pp. 15– 37). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Mincer, J. (1993). Studies in human capital. Brookfield, Ver-mont: Edward Elgar.

Royalty, A. B. (1996). The effects of job turnover on the

train-ing of men and women. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 49 (3), 506–521.

Sandell, S. H. (1987). Prospects for older workers: the demo-graphic and economic context. In S. H. Sandell, The prob-lem isn’t age: work and older Americans (pp. 3–33). New York: Praeger.

Veum, J. R. (1993). Training among young adults: who, what kind, and for how long? Monthly Labor Review, August, 27–32.