Volume 8 Number 2 2011 www.wwwords.co.uk/ELEA

Media Literacy Pedagogy: critical and

new/twenty-first-century literacies instruction

NALOVA WESTBROOK

Language, Culture, and Society Program,

Department of Curriculum and Instruction,

Pennsylvania State University, USA

ABSTRACT This article offers a conceptualization of media literacy pedagogy in light of National Education Technology Plan efforts, which name teaching as one of five essential areas to build an education system that can increase as well as sustain the United States’ economic growth and

prosperity in the global economy. In particular, two distinct forms – critical media literacy, with origins in the Frankfurt and cultural studies tradition, and new/twenty-first-century literacies instruction, the result of socio-linguistic and ethnographic traditions – can be evaluated from Fenstermacher & Richardson’s quality in teaching model that includes assessment based on the process-product paradigm, cognitive science, and constructivism. This article concludes that, while all three of these research programs may help to gauge media literacy models of pedagogy in general, constructivism, and to a lesser extent cognitive science, may be the most appropriate paradigms.

Ways in which to teach media literacy have caught the attention of federal stakeholders, in so far as such instruction can help to leverage the world standing of the United States’ economy. The current Obama administration is pouring millions of dollars into ‘connected teaching’, a frame that helps K through 12 teachers of all subject matters to improve their practice by being connected – virtually speaking – to all kinds of media technology, which would allow twenty-four-hour access to the latest trends in their respective subject fields. This access is presumed to optimize learning performance outcomes of our students. Meanwhile, one could argue that literacy educators, who have adopted media literacy pedagogy, have been at the forefront of advancing the connected teaching model, perhaps albeit unknowingly, for decades to stay abreast of cutting-edge media texts, tools, and technologies (Hobbs, 2007) that influence the out-of-school literacy practices of our nation’s kids. In particular, pedagogues of critical and new/twenty-first-century literacies embrace technology-laden – though not necessarily technology-driven – instruction that challenges hierarchical readings of various media and acknowledgement of students’ use with media as a segue into development of higher-order skills such as critical thinking and problem-solving (NCTE, 2007). Accordingly, one might argue then that connected teaching, from a media literacy standpoint, can best be realized from a quality in teaching model that makes use of constructivism and, to some extent, cognitive science more than conventional process-product teaching.

for educators to assess and evaluate media literacy pedagogy. The article concludes that constructivism and cognitive science may be the most appropriate lenses through which to gauge media literacy pedagogy because of their teacher-as-facilitator and teacher-as-motivator grounding. However, media literacy pedagogues should not fully abandon the process-product paradigm tradition, which may remind practitioners of the importance of factual knowledge in the media literacy curriculum.

Media Literacy Pedagogy Conceptual Framework

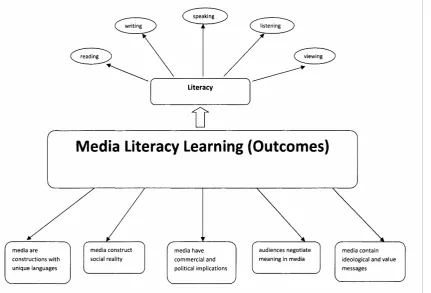

A theoretical framework of media literacy pedagogy can be informed by a clear conceptual demarcation of media literacy learning outcomes, which one may take from the notion of literacy as noted in many state English language arts standards (Hobbs, 2007), as well as from common core principles of media literacy from the broader field of media literacy education. This media literacy learning model includes, as shown in Figure 1, how literacy is an amalgam of reading and writing, as well as listening, speaking, and viewing. According to Elizabeth Thoman (2003), media literacy is predicated, on several core principles in conjunction with each other: (1) Media are constructions with unique language; (2) Media construct social reality; (3) Media have commercial and political implications; (4) Audiences negotiate meaning in media; (5) Media contain ideological and value messages. In other words, Figure 1 represents, as a whole, a model of what it means to be media literate, particularly in an English language arts context.

Figure 1. Media Literacy Learning (Outcomes).

Despite a considerable body of research on media literacy pedagogy in literacy education and media studies circles, scholars continue to debate each of these terms. The most widely circulating definition of media literacy involves the ability to ‘decode, evaluate, analyze, and produce both print and electronic media’ (Aufderheide, 1993, p. 79). While this definition of media literacy may be a sufficient starting point, any notion of ‘media’ recalls Marshall McLuhan’s (1964) work that underscores media as an amalgam of conventions and codes that drive message construction. ‘Literacy’ is also a contested concept, often conveying several meanings. Nonetheless, for the purposes of this article, literacy can be seen as the process of identifying typographic symbols representing phonemes (Ong, 1982). For the purposes of this article, pedagogy is conceptualized as Freirean styles of instruction that are problem-posing and constructivist in nature (Freire, 1998). Taken together, media literacy pedagogy can be defined as problem-posing and constructivist teaching that nurtures learning to identify, evaluate, and analyze codes and conventions of typographic and post-typographic mediated texts. Such pedagogy also involves the production of, and additional practical work with, various media (Sefton-Green, 1995).

Media literacy education scholars rarely use the words ‘media’, ‘literacy’, and ‘pedagogy’ in a single term. Dan Flemming (1993) popularized ‘media teaching’ at an age when educators were just beginning to acknowledge the role of digital media in media literacy education. ‘Media pedagogy’ (Kellner, 1998) is a common term for practitioners, with emphasis often on the social, contextual aspects of teaching media literacy. Perhaps the closest reference to media literacy pedagogy comes in the form of media literacy instruction (Hobbs & Frost, 1998, 2003), which puts emphasis on distinct instructional strategies over and above reflection on the instruction itself. Reasons for variation in the field stem in part from a school of thought in which media literacy is considered to be part of the broader field of media education, in the same way that literacy is considered to be part of the broader field of literacy education. In other words, some scholars (Masterman, 1997; Buckingham, 2003; Duncan & Tyner, 2003) view media literacy as the product of media education. Indeed, one may observe that the concept of media literacy education is much more the preserve of scholars in the United States, whereas media education is more commonly employed in circles in the external English-speaking commonwealth. What is clear, with lack of reference to a single concept that merges media literacy and pedagogy, as opposed to media literacy and teaching or instruction, is that scholars may be loath to connect explicitly the intimate relationship between media literacy learning and teaching, and reflection on such an educational relationship. The emphasis here on including pedagogy with media literacy is to foreground theory and practice, learning and teaching, task and achievement, as part and parcel of a larger whole.

From this vantage point, the concept ‘media literacy pedagogy’ makes the explicit connection between what Fenstermacher & Richardson (2005)would call quality teaching and media literacy learning. Quality teaching can be explicated as good teaching and successful teaching in terms of the combination of tasks and achievement. When a secondary English teacher engages in content analysis of advertising in Hollywood blockbusters, and students can ultimately identify subtle use of name brand cigarettes, for example, in these visual mediated texts, one might argue that quality teaching has occurred because the pedagogical task of content analysis has achieved media literacy learning as evinced in knowledge of product placement. When a media literacy educator shows students how to evaluate search engine results via Google, one might argue that quality teaching has occurred because the pedagogical task using web analysis led students to demonstrate a keen understanding of search engine optimization; students can explain why certain company websites appear at the top of the search engine above other results. In both instances, drawing from Fenstermacher & Richardson (2005), quality teaching for media literacy pedagogy must rest on the extent to which good teaching (task) and successful teaching (achievement) leads to media literacy learning that the media literacy pedagogue intended.

(p. 189). According to this logic, for media literacy pedagogy to be within the scope of quality teaching, there is the need for the instructor to be engaged in ethical teaching of media, and that would lead students to increased media literacy learning – a position that seems to be in line with what some media literacy educators might call ‘critical media literacy instruction’. For example, a secondary English teacher might engage in a textual analysis of propaganda in George Orwell’s 1984 novel and in a textual analysis of a YouTube version of the same narrative. For such media literacy pedagogy to be high in quality teaching, students would need to demonstrate not only the various ways in which both media (the novel and the YouTube clip) construct propaganda in the achievement sense, but also how the teacher does not pass judgment of one text, such as the novel as being inherently better over the electronic video in a way that underscores a high and low culture divide.

Moreover, the moral code of media literacy pedagogy demands what Paulo Freire would call ‘civic courage’, given that many of the mediated texts that students may find entertaining, teachers and K-12 curriculum administrators may, on the other hand, find unsettling (Flores-Koulish, 2005). This stance could lead to inoculation or protectionist media literacy pedagogy. However, the critical media literacy educator would not necessarily oppose analysis of mediated texts that include what he or she views as vulgar or obscene language and visuals. Instead, the critical media literacy pedagogue would develop strategies that encourage students and the teacher to interrogate their own complicity with or attitude against sex and violence saturation on screen, for example.

Critical Media Literacy Instruction

Conceptualization of media literacy pedagogy also takes into account two distinct forms – critical media literacy instruction, with origins in the Frankfurt and cultural studies tradition, and new/twenty-first-century literacies instruction (New London Group, 1996), the result of socio-linguistic and ethnographic tradition. In a nutshell, critical media literacy brings to the fore the relationship between media literacy and critical literacy (Semali, 2000b, 2003), which challenges canonical texts as well as privileged readings of all texts. Such instruction in media literacy is a directive to cultivate skills in ‘analyzing media codes and conventions, abilities to criticize stereotypes, dominant values, and ideologies, and competencies to interpret the multiple meanings and messages generated by media texts’ (Kellner & Share, 2005, p. 372). The ethos of critical media literacy instruction is grounded in analysis of textual power relations.

technologies – are cites of struggles over meaning (Giroux,1997) that ultimately have real-world implications for the ways in which cultural groups view themselves and the other (Said, 1979). For Semali (2000a), ‘ teaching critical media literacy must aspire to teach the youth in our classrooms, particularly those impressionable groups of individuals in desperate search of identity and a place in the adult world ... critical media literacy [needs] ... to generate a strong commitment to developing a world free of oppression and exploitation’ (p. 287). In essence, critical media literacy pedagogy behooves media literacy educators to move beyond pure textualist forms (codes and conventions) of media analysis to reflect on content teaching that encourages democracy (Jhally & Lewis, 1998).

With such a mantra, what is also an explicit part of critical media literacy pedagogy is its relationship with critical pedagogy (Freire, 1970). More so than media literacy pedagogues, critical media literacy pedagogues aim to challenge not only hierarchies within and between media texts, but also the hierarchies of the ways in which such media texts might be taught in order to empower (Shor, 1992) and transform (hooks, 1994) traditional teacher-centered classrooms into more student-centered cites of knowledge production. For example, in discussing the philospphy of critical media literacy pedagogy, Kellner & Share (2005) observe that ‘a student-centered, bottom-up approach is necessary ... with the student’s own culture, knowledge, and experiences ... [forming the basis of] collaborative inquiry and video production [that] can be ways for students to voice their discoveries’ (p. 371). Furthermore, ‘teaching critical media literacy should be a participatory, collaborative project. Watching television shows or films together could promote productive discussions between teachers and students (or parents and children), with an emphasis on eliciting student views, producing a variety of interpretations of media texts, and teaching basic principles of hermeneutics and criticism’ (Kellner & Share, 2005, p. 373). From this standpoint, critical media literacy pedagogy embraces the idea of connected teaching in which students and media technologies are both co-facilitators in instruction of analysis of media. Building on student knowledge of how to use Flash and to code HTML for critique of the ways in which corporate websites represent women is just as important as tapping into Wikipedia and blogs that offer commentary on the same subject. Students tend to enter the classroom with more exposure to and use with media technologies than their teachers, who often are of a generation that harbors anxiety with those same media technologies (NCTE, 2007). The critical media literacy pedagogue of any age would welcome student media tech-savviness into the classroom, and employ such knowledge as a means to enhance media literacy learning of the entire class, including the learning of the teacher. Critical media literacy centers styles of instruction that empower and transform the ways in which teachers, students, and technologies collaborate to analyze mediated social structures.

New/Twenty-First-Century Literacies Instruction

New/twenty-first-century literacies instruction, while not a mutually exclusive entity from critical media literacy instruction, is concerned more with the ways in which new media (i.e. social networking sites, iPods, VoIP) challenge, re-inscribe, expand and, in many instances, connect in-and out-of-school literacy (Morrell, 2002). In other words, those literacy skills such as viewing in-and writing and listening may be increasingly compromised or enhanced by Web 2.0 networks where end-user writer access questions who ultimately is the author of a particular text (Kist, 2005). Particularly important is addressing the widening gap between the literacies in our society and the literacies of our schools (Baker, 2007). Figure 2 shows the relationship between critical media literacy and new literacies, with media literacy pedagogy as the common dominator of the two. As previously mentioned, this model aims to show that critical media literacy and new/twenty-first-century literacies are distinct, though mutually compatible, forms of instruction and pedagogy for media literacy learning and teaching. Indeed, in the classroom, many teachers of media literacy, particularly in English language arts contexts, may in fact vacillate between the two, and, may not entertain such a theoretical difference.

overlap of the two large ovals conveys the inclusiveness of both approaches in terms of one another, whereas the arrows highlight their distinctiveness. However, the arrows in the model emerge from the same place to indicate a common heritage between critical and new/twenty-first-century literacies instruction and pedagogy.

Figure 2. Media Literacy Pedagogy Model.

engage in use of Instant Messenger (Kaiser, 2010) for intimate communication with friends at home (Hu et al, 2004). A new literacy pedagogue may encourage students to explore how use of this online, synchronous medium influences print literacy as well as other informal learning in what James Gee (2005) might call an ‘affinity space’. The notion of affinity spaces is central to new and twenty-first-century literacies instruction because it calls into question the ways in which use of new media in voluntary circumstances cultivates involuntary literacy learning. Learning may occur as a result of those (online) participants formulating a set of informal rules of communication that become standard ways of communicating, such as with the use of acronyms. Or learning may enhance students’ written and verbal communication, depending on the make-up of the participatory community (Jenkins, 2006). What is important in particular is that students may not necessarily be aware of the literacies they use in relation to Instant Messenger or of how they adopt, transfer, or contest these literate forms of communication for formal schooling literacies. In other words, literacy educators read work of students that may increasingly include heavy use of acronyms from consistent Instant Messenger use and texting via mobile devices.

Such a case should lead educators to ask students what media they are engaged with outside of school in the same way that teachers of English as a second language may inquire about the native language identities of their students who exhibit unconventional syntax structures in their expository writing. Ethnographic roots of such pedagogy entail observing – at the very least acknowledging – and employing strategies such as scaffolding (Abram, 2008) for students to use these social mediated literacies to improve communication (NCTE, 2007). From this standpoint, media literacy is an inherent social process that is the product of social interaction via media. In short, new and twenty-first-century literacies, instruction may demand taking students’ mediated literacy practices in informal, situated spaces to inform formal literacy acquisition.

Another school of thought on new and twenty-first-century media literacy pedagogy is rooted in the idea of developing media literacy skills for future employment (New London Group, 1996; NCTE, 2007). ‘The challenge for our education system is to leverage technology to create relevant learning experiences that mirror students’ daily lives and the reality of their futures’ (US Department of Education, 2010, p. 9). The Department of Education has partnered with leading media industry companies such as Cisco and Apple to infuse media technologies in K-12 schools and teacher education programs that would leverage teaching and learning of higher order thinking. Media literacy educators have marshaled in efforts to develop pedagogies that tap into the ways in which media transform lives and have at times outpaced pedagogies (Semali, 2003). In the digital media literacy explosion, ‘multiple communication channels, hybrid text forms, new social relations, and the increasing salience of linguistic and cultural diversity’ (Hull & Schultz, 2001, p. 589) have opened a means for schools and media industry to form stronger ties, recognizing the importance and the power of the media industry as an increasingly primary stakeholder in many schooling efforts. New and twenty-first-century literacy pedagogy centralizes the phenomenon whereby employers increasingly demand workers who have an ease and intimacy with multiliteracies (New London Group, 1996). That is, cultural, linguistic, and media literacies, for example, are important, particularly knowing when and how to use them to provide services to company clients. Indeed, it is now common practice for many brand marketing departments to employ social media to appeal to customer desires to cultivate brand loyalties. Media literacy skills in the age of convergence culture (Jenkins, 2006) – that is, a culture in which new media are consistently overlapping and merging – will indeed lead to a stronger workforce that can meet employer needs. New and twenty-first-century literacy instruction – and more so pedagogy – address this concern.

Media Literacy Pedagogy Policy

What should stand out in the conceptual model of media literacy pedagogy, particularly in highlighting critical and new/twenty-first-century literacies instruction, is the emphasis on learner-centered education. While connected and quality teaching are not one and the same, the connected teaching frame of the National Education Technology Plan is consistent with the conceptual model of media literacy pedagogy thus far explained via quality teaching. Connected teaching can be viewed as a form of quality teaching because it speaks directly to a policy position that ‘rejects the one size fits all’ approach to learning mired in causality claims of teaching. Fenstermacher & Richardson (2005) observe this trend in conceptions of quality teaching that can inform poor teaching policies:

There is currently a considerable policy focus on quality teaching, much of it rooted in the presumption that the improvement of teaching is a key element in improving student learning. We believe that this policy focus rests on a naive conception of the relationship between teaching and learning. This conception treats the relationship as a straightforwardly causal connection, such that if it could be perfected, it could then be sustained under almost any conditions, including poverty, vast linguistic, racial, or cultural differences, and massive

differences in the opportunity factors of time, facilities, and resources. Our analysis suggests that this presumption of simple causality is more than naive; it is wrong ... the teacher may be viewed as having a kind of limited liability for the success or failure of the learner to acquire the content taught… Improving the quality of what the teacher does is only a part of improving student learning. It is, however, a most important part, one that deserves further scrutiny ... (p. 192)

Such is the position, too, of the National Education Technology Plan that promotes media literacy pedagogical approaches in favor of individualized instruction that builds on prior experience of each learner within context. This policy position reflects a clear constructivist epistemology. Consider another passage of the National Education Technology Plan that invites consideration of the non-causality approach lauded by Fenstermacher & Richardson (2005), by rejecting the teacher as transmitter and the sole standards-based perspective:

In contrast to traditional classroom instruction, which often consists of a single educator

transmitting the same information to all learners in the same way, the model puts students at the center and empowers them to take control of their own learning by providing flexibility on several dimensions. A core set of standards-based concepts and competencies form the basis of what all students should learn, but beyond that students and educators have options for engaging in learning: large groups, small groups, and work tailored to individual goals, needs, and

interests. (US Department of Education, 2010, p. 10)

What the National Education Technology Plan promotes is collaboration among media literacy teaching and learning, where teachers and media technologies provide a matrix for learner-centered classrooms. Current federal policy of this sort foregrounds media literacy of ‘technology for ownership of learning’, in which students, just as much as teachers, take a leadership role for what they know, increasingly because of the twenty-four-hour ‘on-demand opportunities for learning’ (US Department of Education, 2010).

Reading Media Literacy Pedagogy: teaching paradigms perspective

instance, than it is with the ability to demonstrate critical analysis of the ways in which soap operas cater to specific media consumer groups and how a Jay-Z single changes across MP3 players, iPods, and Blackberries. Instead, quality instruction of media literacy can be gauged more from the vantage point of two paradigms of research on teacher education – namely, cognitive science and, as previously mentioned, constructivism.

While constructivist learning has already been demonstrated as the primary framework through which media literacy pedagogical and policy commitments can be sustained, it is also important for media literacy educators to keep in mind the cognitive science element of media literacy. One might argue that quality teaching of media literacy pedagogy centers on what NETP proponents would call ‘motivational engagement’. Any pedagogue who proclaims the importance of quality instruction of media literacy is likely to find high levels of motivation among his or her learners. Of course, when students have the opportunity to engage in evaluation of popular culture representation of Lady Gaga, or to conduct a semiotic analysis of a Victoria’s Secret magazine advertisement, there is an unquestioned sense that they will yearn to participate in problem-posing teaching.

Still, the cognitive science component to the evaluation of media literacy pedagogy can be viewed more along the crossroads between process-product and constructivist teaching. Cognitive teaching approaches aim to get at instruction that enhances cognition largely through more complex learning outcomes, such as critical thinking and problem solving, and self-direction (US Department of Education, 2010). Quality teaching of media literacy pedagogy – broadly-speaking – is to be evaluated in part on the basis of the extent to which teachers can develop activities that enhance motivation and these divergent cognitive abilities. Indeed, media literacy educators may deem their teaching successful if their students, after participating in a deep viewing exercise (Paillotet et al, 2000), show awareness of how much subtle acts of violence in popular culture are pervasive by producing iMovies that offer alternatives to aggression and physical force-laden narratives. However, in this sense, one would argue that cognitive science is a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition through which one should approach media literacy pedagogy or exclusively evaluate its effectiveness.

Conclusion: Process-Product Paradigm Still Important, Just Not Paramount

References

Abram, S. (2008) Scaffolding the new social literacies, Multimedia & Internet@Schools, March/April. Adorno, T. & Horkheimer, M. (1999) The Culture Industry: enlightenment as mass deception, in S. During

(Ed.) The Cultural Studies Reader, pp. 31-41. New York: Routledge.

Aufderheide, P. (1993) Media Literacy: a report of the national leadership conference on media literacy. Aspen, CO: Aspen Institute.

Baker, E.A. (2007) Support for New Literacies, Cultural Expectations, and Pedagogy: potential and features for classroom websites, New England Reading Association Journal, (43)2, 56-62.

Buckingham, D. (2003) Media Education: literacy, learning and contemporary culture. London: Polity Press. Duncan, B. & Tyner, K. (Eds) (2003) Visions/Revisions: moving forward with media education. Madison, WI:

National Telemedia Council.

Fenstermacher, G.D. & Richardson, V. (2005) On Making Determinations of Quality in Teaching, Teachers College Record, 107(1), 186-213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2005.00462.x

Flemming, D. (1993) Media Teaching. Oxford: Blackwell.

Flores-Koulish, S. (2005) Teacher Education for Critical Consumption of Mass Media and Popular Culture. New York: Routledge.

Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum: Freire, P. (1998) Pedagogy of Freedom. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gee, J. (2005) Semiotic Social Spaces and Affinity Spaces, in D. Barton & K. Tusting (Eds) Beyond Communities of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giroux, H. (1997) Pedagogy and the Politics of Hope: theory, culture, and schooling. Boulder, CO: Westview. Hall, S. (1973) Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary

Cultural Studies, University of Birmingham.

Hall, S. (1997) Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices. London: Sage/Open University. Hobbs, R. (2007) Reading the Media: media literacy in high school English. New York: Teachers College Press. Hobbs, R. & Frost, R. (1998) Instructional Practices in Media Literacy Education and their Impact on

Students’ Learning, New Jersey Journal of Communication, 6(2), 123-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.38.3.2

Hobbs, R. & Frost, R. (2003) Measuring the Acquisition of Media-Literacy Skills, Reading Research Quarterly, 38(3), 330-355.

hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to Transgress: education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Hu, Y., Fowler-Wood, J., Smith, V. & Westbrook, N. (2004) Instant Messenger and Intimacy: examining the relationship between Instant Messenger and friends, Journal of Computer-Mediated-Communication, 10(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00231.x

Hull, G. & Schultz, K. (2001) Literacy and Learning out of School: a review of theory and research, Review of Educational Research, 71(4), 575-611. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543071004575

Jenkins, H. (2006) Convergence Culture: where old and new media collide. Journal of Education, 37(2), 182-197. New York: New York University.

Jhally, S. & Lewis, J. (1998) The Struggle over Media Literacy, Journal of Communication, 48(1), 109-120. Kaiser Family Foundation (2010) Generation M2: media in the lives of 8-18 year olds. Menlo Park: Kaiser

Family Foundation. http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf

Kellner, D. (1998) Multiple Literacies and Critical Pedagogy in a Multicultural Society, Educational Theory, 48(1), 103-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.1998.00103.x

Kellner, D. & Share, J. (1998) Multiple Literacies and Critical Pedagogy in a Multicultural Society, Educational Theory, 48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.1998.00103.x

Kellner, D. & Share, J. (2005) Toward Critical Media Literacy: core concepts, debates, organizations, and policy, Discourse, 26(3), 369-386. http://dx.doi. org/10.1080/01596300500200169

Kist, W. (2005) New Literacies in Action: teaching and learning in multiple media. New York: Teachers College Press.

Masterman, L. (1997) A Rationale for Media Education, in R. Kubey (Ed.) Media Literacy in the Information Age, pp. 15-68. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Morrell, E. (2002) Toward a Critical Pedagogy of Popular Culture: literacy development among urban youth,

Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 46(1).

National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) (2007) 21st-Century Literacies: a policy research brief produced by the National Council of the Teachers of English. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

New London Group (1996) A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: designing social futures, Harvard Education Review, 66(1), 60-92.

Ong, W.J. (1982) Orality and Literacy: the technologizing of the word. London: Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203328064

Pailliotet, A.W., Semali, L., Rodenberg, R.K., Giles, J.K. & Macaul, S.L. (2000) Intermediality: bridge to critical media literacy, The Reading Teacher, 54(2), 208-219.

Quin, R. & McMahon, B. (1993) Monitoring Standards in Media Studies: problems and strategies, Australian Journal of Education 37(2), 182-197.

Said, E. (1979) Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

Sefton-Green, J. (1995) Neither ‘Reading’ Nor ‘Writing’: the history of practical work in media education,

Changing English, 2(2), 77-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1358684950020205

Semali, L. (2000a) Implementing Critical Media Literacy in School Curriculum, Advances in Reading/Language Research, 7, 277-298.

Semali, L. (2000b) Literacy in Multimedia America. New York: Falmer Press.

Semali, L. (2003) Ways with Visual Languages: making the case for critical media literacy, The Clearing House, 76(6), 271-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00098650309602018

Semali, L. & Hammett, R. (1999) Critical Media Literacy: content or process? Review of Education/Pedagogy/Cultural Studies, 20(4), 365-384.

Share, J. (2009) Media Literacy is Elementary: teaching youth to critically read and create media. New York: Peter Lang.

Shor, I. (1992) Empowering Education: critical teaching for social change. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Shulman, L. (1987) Knowledge and Teaching: foundations of the new reform, Harvard Educational Review, 57, 1-22.

Silverblatt, A. (2008) Media Literacy: keys to interpreting media messages, 3rd edn. Westport, CT: Praeger. Thoman, E. (2003) Media Literacy: a guided tour of the best resources for teaching, The Clearing House, 76(6),

278-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00098650309602019

US Department of Education (2010) Transforming American Education: learning powered by technology. Report by Office of Educational Technology. Washington, DC: Office of Educational Technology, US Department of Education.