Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 19:54

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Liquidity support to banks during Indonesia's

financial crisis

J. Soedradjad Djiwandono

To cite this article: J. Soedradjad Djiwandono (2004) Liquidity support to banks during Indonesia's financial crisis , Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 40:1, 59-75 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0007491042000205204

Published online: 12 Jul 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 129

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/04/010059-17 © 2004 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/0007491042000205204

LIQUIDITY SUPPORT TO BANKS

DURING INDONESIA’S FINANCIAL CRISIS

J. Soedradjad Djiwandono*

University of Indonesia, Jakarta, and Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

During the 1997–98 financial crisis, Bank Indonesia provided liquidity support to many banks experiencing difficulties. This policy became controversial because of the magnitude of the likely losses to the government, which in the end would have to be borne by the general public. Suspicions of corruption involving bankers and officials of Bank Indonesia fuelled the debate. Surprisingly, however, concerns of this kind have not been raised in relation to the far larger amount of support provided to banks by the government in the form of recapitalisation bonds. The public’s lack of understanding of the operations of the banking sector further com-plicated the debate. This paper attempts to shed some light on the central bank’s actions and on the proposed solutions to the problems that arose from them.

INTRODUCTION

Several steps taken by Bank Indonesia (BI, the central bank) during the first sev-eral months of the financial crisis that began in mid 1997 have become the subject of public controversy, particularly the provision of liquidity support to banks.1

This policy was intended to prevent the collapse of the banking industry and the national payments system during the crisis, but it became controversial following the issue of two reports by the Supreme Audit Agency (Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan, BPK) after its audits of BI. The first reported the results of a general audit, and was issued by the agency in November 1999. It was accompanied by a disclaimer indicating that the auditor could not obtain sufficient information to make a conclusive evaluation. The second, the report of an investigative audit requested by the parliament was issued in July 2000. This report confirmed the suspicion of possible criminal acts, either in the use of funds by the recipient banks or in the provision of funds by the central bank, or both (BPK 2000).

In February 2000 the Parliamentary Working Committee on BLBI (Bantuan Likuiditas Bank Indonesia, BI Liquidity Support) summoned officials and former officials of BI and the Ministry of Finance to testify on the question of whether the central bank or the government had initiated the liquidity support policy. This led to public debate after a statement during the proceedings by three former ministers of finance (Mar’ie Muhammad, Fuad Bawazier and Bambang Subianto) that the central bank’s actions were based on its misunderstanding of actual gov-ernment policy. According to the former ministers, the govgov-ernment’s involve-ment in liquidity support for banks was by way of a Presidential Instruction dated 3 September 1997, issued after a cabinet meeting that day. They testified

that the central bank did not consult the Ministry of Finance in implementing this instruction (Sukowaluyo 2001: 27–31).

The liquidity support issue had already been raised in news and gossip circu-lating on the internet as early as November 1997. In some writings it was alleged that BI had been secretly helping a number of large ethnic Chinese conglomerate-owned banks, such as BCA (Bank Central Asia), Danamon, BUN (Bank Umum Nasional) and Lippo, with liquidity support amounting to trillions of rupiah. In November 1997, these writings were collected and published in a booklet entitled

Konspirasi Menggoyang Soeharto [Conspiracy to Topple Soeharto] (Anonymous 1997). The public perceived the conglomerates as symbols of the social ills of Indonesia—in particular, the corruption, collusion and nepotism of the Soeharto era. Some argued that bankers and bank owners were the beneficiaries of funds provided by BI as liquidity support to their banks—and that they constituted the group that, in cooperation with BI officials, had caused the near bankruptcy of the economy. It was therefore unfair, so the argument continued, that the general public had to bear the burden of bailing out these conglomerates. This is a very appealing argument, but it is flawed nonetheless.

The public’s perception of these matters appears to have been worse than the reality. The decision to provide liquidity support to banks suffering distress caused by bank runs was in line with the central bank’s function as lender of last resort, and in conformity with the government’s then policy of not closing banks. But in circumstances of non-transparency and weak governance, the public’s pre-conceptions about the banking system, and its lack of information about how the system functioned, meant that the decision was bound to generate controversy.

WHAT IS LIQUIDITY SUPPORT?

Liquidity support is funding provided by a central bank to banks suffering a liq-uidity shortfall as a result of negative net cash flow; it may be extended on vary-ing terms, dependvary-ing on the precise nature of the liquidity problems the banks face. As lender of last resort and guardian of the payments system, BI had intro-duced various schemes of liquidity support since its transformation from the old De Javasche Bank in 1953 into the central bank of the new republic. Although the public was reasonably familiar with the discount window or rediscount facility, the term ‘BI liquidity support’ only became widely known in early 1998, when it was alluded to in the government’s second letter of intent (LOI) to the IMF (GOI 1998: paragraph 15).

The term BLBI includes all lending by the central bank to the banking sector other than BI Liquidity Credits (Kredit Likuiditas BI, or KLBI); the latter are loans provided to commercial banks at subsidised interest rates to support government programs such as finance for small and medium scale enterprises, cooperatives and the logistics agency, Bulog. Using this broad definition, we can identify as many as 15 different facilities that BI has employed to provide liquidity to banks. These can be grouped into the following five categories:

1 Liquidity support to banks suffering shortfalls due to unexpected net cash outflows.

This was of two types: one that bore a very short term of 15–30 days and was unsecured, termed Discount Facility I, and another for short terms of 90–150

days, termed Discount Facility II. The latter required promissory notes as col-lateral.

2 Liquidity support through open market operations. This facility involved BI re-discounting promissory notes or other debt instruments of commercial banks (known collectively as Surat Berharga Pasar Uang, SBPU), either through peri-odic auctions or through direct deals with banks in need.

3 Liquidity support in the context of bank rescues or ‘nursing programs. This involved emergency and subordinated loans from BI to problem banks that were in the process of being restructured through mergers or acquisitions.

4 Liquidity support to banks facing runs, provided to stabilise the banking industry and the payments system. This facility allowed banks to overdraw their accounts with the central bank without being excluded from the clearing (the daily process of adjusting each bank’s balance in its clearing account with BI after recording the impact of all cheques and other payment orders drawn against it or in its favour).

5 Liquidity support provided to defend market confidence in the banking sector. These facilities were in the form of advances by BI (on behalf of the government) to compensate banks for taking over deposits previously held at other banks that were to be liquidated, and to pay Indonesian banks’ arrears to their foreign counterparts in relation to trade financing and interbank debt exchange offers.

The first two categories of liquidity support are similar to instruments that most central banks provide in their capacity as monetary authorities and lenders of last resort, and they had long been used by BI in its day-to-day operations. BI had also resorted to the third and fourth types before the crisis in its attempts to restructure certain problem banks. In other words, these four forms of liquidity support were in use by BI in the normal conditions that existed before mid 1997. The use of the fourth type of liquidity support, however, was greatly expanded during the crisis as a means to avoid collapse of the entire banking system, while the fifth arose during the crisis as a result of BI acting on behalf of the government in meeting the claims of depositors and of foreign bank creditors of closed and troubled domestic banks. The overdraft facility (type 4) was quantitatively the most significant of the five types of liquidity support. Before going on to discuss this, it will be helpful to provide some background on BI’s attempts to deal with troubled banks in the last few years before the crisis.

STALLED ATTEMPTS TO DEAL WITH PROBLEM BANKS

In dealing with problem banks in the past, BI had adopted a case-by-case approach, whereby it could take a variety of steps to restore a bank’s health before resorting to liquidation. These steps, set out in article 37 of the 1992 bank-ing act, ranged from requirbank-ing the bank to increase capital or change its manage-ment to assisting it to undergo merger with or acquisition by interested investors. If all these efforts failed to make the bank healthy, it would then be liquidated. In other words, bank closure was considered the last option, after all other alterna-tives had been exhausted. BI interpreted article 37 as reflecting a view that the sta-bility of the banking sector, as an integral part of the national payments system, was crucial for the central bank to conduct its operations.

The case-by-case method was discarded when BI was faced with an increasing number of problem banks following the weakening of the economy toward the end of the 1980s and in the early 1990s.2Instead, a more systemic approach was

adopted. In December 1996, together with two managing directors in charge of bank supervision, I submitted a proposal to President Soeharto for the closure of seven insolvent banks, after various efforts to overcome their problems had failed. Unfortunately he did not approve this proposal, and instead instructed BI to finalise a draft government decree on bank closures.3

At the time there was no specific regulation on bank liquidation, even though this was provided for in the banking law of 1992. This implied that if a bank were to be liquidated, the general liquidation regulations for ordinary corporations would need to be applied. A problem here was that a liquidator could not treat depositors as priority creditors in the distribution of proceeds from disposal of the banks’ remaining assets. In other words, the payment to depositors of liqui-dated banks could only be done in parallel with payment to other creditors, as had been the case with the long drawn out liquidation of Bank Summa in 1992 (MacIntyre and Sjahrir 1993: 12–16). Because of this consideration and the presi-dent’s disinclination to see banks liquidated, there had been no further bank clo-sures up to this time.

In April 1997, BI again proposed the liquidation of the seven problem banks, since their status had not improved. This time the president gave his approval. However, he instructed BI to postpone implementation until after the general election in October 1997 and the general session of the Peoples’ Consultative Assembly (MPR) in March 1998, because of his concern over the implications of bank closures for social and political stability. Unfortunately, the financial crisis intervened in July 1997. As conditions deteriorated the number of problem banks increased, but BI did not have the option of closing them, because of the presi-dent’s instruction to avoid any closures until after the MPR session.

LIQUIDITY SUPPORT TO ADDRESS THE BANKING CRISIS

The government’s decision to float the rupiah on 14 August 1997 (Lindblad 1997: 4–5) proved a shock to Indonesian businesses. Uncertainty about the exchange rate created panic among those members of the business community that had high levels of foreign exchange exposure. They began to buy dollars heavily, while other parties that might normally have been expected to supply dollars to the market failed to do so, causing the currency to depreciate rapidly.4

To defend the currency the authorities responded by implementing a severe liquidity crunch, through a combination of expenditure reductions by the govern-ment and administrative intervention; the latter took the form of an instruction from the finance minister to state enterprises to switch their bank deposits into BI Certificates (SBIs).5 The SBI interest rate was also increased significantly at this

time, but this would have had little effect, since market rates rose to much higher levels still as a result of these other actions. In August the average interbank rate rose from 20% to 90% p.a.—reaching as high as 200% for one or two days—mak-ing the purchase of SBIs unattractive to market participants. Indeed, one symp-tom of the severity of the liquidity squeeze was that a number of banks sold SBIs back to BI before they matured.

At much the same time, depositors began to withdraw funds from banks per-ceived to be weak, thus significantly exacerbating the impact on the banks of the system-wide liquidity squeeze. The banking industry became distressed, and many banks’ clearing balances fell to negative levels. Banks that still had excess liquidity at this time chose to hold on to it for precautionary reasons, rather than lending to other banks. Thus banks faced with net cash outflows were forced to draw on funds deposited with BI in fulfilment of their reserve requirement, caus-ing these to fall below the regulatory minimum: the number of banks failcaus-ing to meet the requirement rose from 14 on 15 August to 51 by the end of the month. When massive deposit withdrawals continued, the remaining reserves were quickly exhausted, and many banks began to have negative balances with BI; by the end of the year 29 banks suffered from this problem.

With the benefit of hindsight, it can be seen that the liquidity squeeze resulting from defence of the rupiah after its float was too stringent, resulting in a severe blow to the banking system. As it became aware of this, the government specifi-cally instructed BI to provide liquidity support on a discretionary basis to banks experiencing liquidity problems. This policy was introduced on 3 September 1997, prior to the commencement of the IMF program, in the form of a set of directives by the president to the cabinet (GOI 1997a).

In normal conditions, any bank that experienced a negative balance with the central bank at the end of the daily clearing process was given one day to settle the obligation, in accordance with a BI regulation adopted in 1990, which stipu-lated that a bank that failed to do so would be excluded from the clearing process.6The Supreme Audit Agency’s report on BI drew attention to this

regu-lation, which has become a rallying point for critics of BI management’s continu-ing to provide liquidity support rather than haltcontinu-ing many banks’ operations. The regulation was not intended to apply in abnormal circumstances that threatened a collapse of the banking system, however. As we have seen, BI interpreted arti-cle 37 of the banking act as requiring it to take whatever measures it considered necessary to safeguard the stability of the banking system. Ordinarily, a bank would restore its clearing balance by borrowing funds from other banks in the interbank money market. It could also request BI to provide additional liquidity but, as long as funds were available to it in the interbank money market, the bank would avoid using the BI facility, since it bore a much higher penalty rate of inter-est; in addition, this would result in its financial problems being exposed to other banks.

Liquidity support in normal conditions mainly took the form of discount facil-ities and the rediscount of banks’ promissory notes, which provided reasonable security for BI. The procedure was somewhat cumbersome, however, and in the face of system-wide liquidity shortfalls, speed is essential if support is to be effec-tive in safeguarding the payments system (Sheng 1998). Thus BI decided to help banks that had negative balances with it by allowing them to continue to partic-ipate in the clearing. This modification of the usual practice permitted the banks to operate normally, thus maintaining the functioning of the payments system, and giving the banks a chance to overcome their liquidity problems and to repay their debts to the central bank later on. The alternative would have been wide-spread liquidation of distressed banks, with the disposal of their assets and liabil-ities effected through bankruptcy proceedings. Such an outcome would have

been inevitable given the level of public confidence in the banking system, which was so low that even a groundless rumour about a bank suffering a shortfall in the clearing could lead to a run on that bank. Indeed, on several occasions during this period banks suffered runs as a result of such rumours. Any announcement by BI barring a bank from the clearing would have amounted to a ‘nail in its cof-fin’, and if such an announcement had involved a number of banks it would have generated widespread bank runs.

In summary, in the first few months of the crisis BI provided liquidity support to banks that were in need of it, in accordance with its function as lender of last resort, and in defence of the banking industry and the payments system. The liq-uidity support was made available to banks without discrimination; it was cer-tainly not restricted to banks owned by Soeharto’s cronies or to any other group.

The disadvantage of allowing banks with negative clearing balances to con-tinue to participate in the clearing was that there were no safeguard measures to protect BI. But the expectation was that the crisis would be over quickly, and that the banks would soon be able to regain lost deposits; in the meantime, the bank-ing industry would be saved from collapse. In the event, however, the cost of pro-viding unsecured liquidity support proved to be very high. We do not know what the outcome would have been if, instead of being provided with liquidity sup-port, banks had been barred from the clearing, as critics of BI liquidity support seem implicitly to advocate. Argentina in November 2001 and Uruguay in July 2002 elected to limit the withdrawal of deposits from banks, which would have had much the same effect as barring banks from the clearing. It remains to be seen what the end result of this policy will be, but it has been reported that the deci-sion caused social and political turmoil in Argentina at least (Ashari 2002; Mongid 2002; Mussa 2002).

BANK CLOSURES

With the rapid deterioration of economic conditions during September and Octo-ber 1997, the government turned to the IMF for assistance. A prominent feature of the program decided upon was the closure on 1 November of 16 small banks, including the seven banks whose liquidation BI had earlier proposed. During dis-cussions with IMF staff I pointed out that BI was already fully prepared to close these seven banks (and that I had brought this to the attention of the president before the crisis), but I also stated that my staff needed more time to prepare for the closure of other banks. The IMF staff repeatedly asked me not to worry too much, however. As Dr Bijan Aghevli, chief of the IMF negotiating team, pointed out, the 16 banks constituted only 3% of the total assets of the Indonesian bank-ing industry.

In fact, the turmoil in the banking sector became even more severe following the closure of these 16 banks, leading the banking industry to lose credibility. Depositors reacted by moving a large amount of funds to banks considered safe, and the interbank money market became segmented: it functioned well enough for the ‘safe’ banks, but not for the many others that lost deposits. The source of the problem was not just withdrawals by depositors, but also the termination of lines of credit by foreign banks for trade financing. Thus the number of banks suf-fering liquidity shortfalls increased further, resulting in a crisis for the banking

sector as a whole. The government addressed the systemic liquidity problem of banks by issuing a blanket guarantee of the banks’ liabilities and by creating a special institution on 26 January 1998 to deal with problem banks, the Indonesian Banking Restructuring Agency (IBRA). It also assisted banks in meeting payment of trade financing arrears with foreign banks.7 Meanwhile, the previously

announced policy of avoiding additional bank closures was restated by President Soeharto in an attempt to prevent further loss of public confidence in the bank-ing system. After signbank-ing the second LOI to the IMF on 15 January 1998, the pres-ident stated that the government would not liquidate more banks, but would urge those experiencing difficulties to merge with others; meanwhile, banks would be subject to more stringent supervision than in the past (Suara Pembaruan, 16/1/98).

As the financial turmoil developed into a prolonged economic crisis, banks faced an increasing volume of non-performing loans; the initial liquidity problem had now become one of widespread insolvency. Since the closure of all banks that had become insolvent would almost have wiped out the banking sector, in August 1998 the government initiated a program of bank restructuring involving recapitalisation of both state-owned and private banks (Fane and McLeod 2002). The plan was for owners of problem banks to provide 20% of the capital needed to raise the banks’ capital adequacy ratios (CARs) to 4%, and for the government to provide the remaining 80%. Thus the focus of government policy switched from the provision of liquidity support by the central bank to making good banks’ losses through the injection of government bonds, the repayment of which would be a call on the budget.

As policies for addressing problems encountered by banks during the crisis, liquidity support and recapitalisation have not been fundamentally different, in the sense that both were intended to help banks address problems arising from the lack of funds needed to fulfil operational requirements. Liquidity support supplemented the banks’ short-term assets so as to meet short-term payment obligations, while recapitalisation injected new long-term assets to make good accumulated losses, and thus to enable banks to meet the minimum CAR. In a sense, therefore, BI’s liquidity support can be seen as a down-payment on guard-ing the bankguard-ing system from collapse. It should be noted that the amount of funds eventually committed by the government through recapitalisation (around Rp 431 trillion) far exceeds the amount of BLBI (Rp 179 trillion). It is therefore sur-prising that only BI has been so heavily criticised in relation to the banking crisis, even though the government has supplied a far larger share of the funds needed to support the banks, and has even been commended for its recapitalisation policy.

THE CONTROVERSY OVER LIQUIDITY SUPPORT

The provision of liquidity support became controversial when its financial impli-cations began to become clear, and allegations of corruption in the process began to emerge, as a result of which ‘ownership’ of the policy became an issue. Here it is relevant to look at the government’s policy making role—as distinct from that of BI—in this area. As we have seen, BI’s initial decision to allow banks to con-tinue to operate despite having negative balances with it was based on its role as

lender of last resort, on the one hand, and the president’s instruction not to allow any bank closures until after the March 1998 MPR session, on the other.

The 3 September 1997 directives from the president referred to above modified this earlier instruction to some extent, however. On liquidity support, the direc-tives confirmed that healthy national banks suffering from liquidity problems should temporarily be provided with additional liquidity. But it was now explic-itly stated that banks that were clearly unhealthy should be put under a program of merger and acquisition with healthy banks, and that if this effort failed they would be liquidated, with a view to protecting the interests of deposit holders, especially small depositors (GOI 1997a: point 8).

This raises questions about why unhealthy banks received liquidity support, why there were no bank closures immediately after the issuing of this instruction, and why there were no mergers or acquisitions of banks until much later. Part of the explanation is that the president saw bank closures very much as a last resort, as indeed was the underlying rationale of article 37 of the banking law. The deci-sion to proceed with some closures was taken only in October 1997, as a ‘prior action’ required by the IMF-supported program.8 In essence, the president’s

opposition had been overcome with the help of pressure from the IMF during its initial negotiations with the government. (Even so, his position was soon reversed, when many banks faced severe runs after the first group of bank clo-sures in November 1997 generated a very negative public reaction.) The govern-ment promised in November 1997 not to liquidate more banks, and at the same time it announced new economy policies for the real sector. The minister of trade and industry, the finance minister and I as governor of BI announced the overall policy package after we had reported to President Soeharto in his office (Kompas, 4/11/97).

What about bank mergers? This was not something that could be done overnight. However, preliminary moves had commenced immediately follow-ing the announcement of the government’s policy package of 3 September 1997. With respect to the state banks, initially the plan was to deal first with the down-sizing and merger of two insolvent banks, Bank Bumi Daya and Bapindo. In a document (‘side letter’) that accompanied the first LOI (but that was never made public), it was stated that these banks would be merged by December 1997, after separating their ‘good’ from their ‘bad’ assets. Before this merger could be implemented, however, it was decided instead, in January 1998, to extend it to include Bank Dagang Negara (BDN) and Bank Ekspor Impor Indonesia (Exim); the merged entity was later to become Bank Mandiri. With respect to the private banks, the process was even slower. By December 1997, with the assistance of BI as mediator, a number of banks had produced memoranda of understanding that formally stated their intention to merge, but without any concrete timetable for doing so.

Opposition from the president aside, it is important to appreciate that imple-mentation of mergers and acquisitions requires considerable time. Banks only became willing to proceed with them toward the end of 1997; in the interim, while negotiations between the banks and potential investors were under way, there was nothing BI could do other than to help those in need of additional liq-uidity. In any case, the government’s policy on provision of, and ultimate respon-sibility for, liquidity support to banks was clearly stated in the first LOI to the IMF

(GOI 1997b), which detailed the government’s program for addressing the crisis, including the initial bank closures. Relevant points included the following:

• The government guaranteed small deposits at the banks that were to be liqui-dated, up to a maximum of Rp 20 million each (around $5,000 at the time). Pay-ments to the depositors in question were to be administered by BI and funded by the government (GOI 1997b: paragraph 26, emphasis added).

• BI would streamline its lender of last resort function. Loans to illiquid but sol-vent banks would be provided in accordance with stringent access conditions. These loans would be collateralised and extended to individual institutions at increasingly punitive interest rates. Any emergency assistance to banks to pre-vent systemic risks would be explicitly guaranteed by the government(GOI 1997b: paragraph 36, emphasis added).

The liquidation of the 16 banks in November 1997 was one of the pillars of the government’s IMF-supported adjustment program. Note the explicit stipulations that the government would bear the cost of bailing out small depositors and would guarantee any financial assistance to overcome systemic risks.

In the second LOI it was explained that the central bank’s liquidity support to the banking sector was intended to defend the banking system from collapse:

By mid-November, a large number of banks were facing growing liquidity shortages, and were unable to obtain sufficient funds in the interbank market to cover this gap ... At the same time, another smaller group of banks were becoming increasingly liquid, and were trading among themselves at a relatively low JIBOR (Jakarta Interbank Offer Rate) ... As this segmentation continued to increase, while the stress on the banking sys-tem intensified, Bank Indonesia was compelled to act. It provided banks in distress with liquid-ity support, while withdrawing funds from banks with excess liquidliquid-ity ... (GOI 1998: paragraph 15, emphasis added).

This passage shows that the policy of providing liquidity to banks during the crisis was a step that the central bank was compelled to take in an effort to pre-vent the banking sector and payments system from collapsing. The decision was based on article 32 (3) of the Central Bank Act of 1968, which gave BI, as lender of last resort, the authority to provide banks with the liquidity they needed in the face of runs. The decision was also based on the explicit 3 September 1997 instruc-tion from the president to BI to help banks with liquidity problems.

In late January 1998, the government announced a full (‘blanket’) guarantee to depositors and creditors of all nationally incorporated banks. Claims against this guarantee were also to be borne by the government budget. In late February 1998, the government decided to extend this guarantee to all deposits that had been held at the previously liquidated banks, not just those of small depositors.

From the sequence of decisions by the government (or the president) and BI as outlined above, the ownership of the policy of providing liquidity support to the banking sector and the resulting burden of financing is clear. And yet, after BI was granted autonomy with the enactment of Law No. 23/1999 on Bank Indo-nesia, and when the worst period of the crisis was over, the question of owner-ship of the policy, and the question of who should be made accountable for its costs, became political issues.

Contrary to the claim by the three former ministers of finance and others dur-ing the parliamentary heardur-ing in February 2000, the decision by BI to provide liq-uidity support to the banking sector was not an incorrect interpretation of government policy, nor was it in violation of the Central Bank Act. In other words, it was not an action that implied any misuse of the power or authority bestowed on BI and its board of directors (of which I, as governor, was chairman). Indeed, in its report on the investigation into the issue of liquidity support, the Parliamentary Working Committee concluded that the decision that BI would provide liquidity support was a government policy based on abnormal crisis con-ditions (BI 2002: 94; DPR 2000).

PROVIDING LIQUIDITY SUPPORT TO FRAGILE BANKS

Critics of the policy of providing banks with liquidity support have questioned why BI allowed banks to overdraw their accounts, which amounted to making unsecured loans to them, instead of providing the usual discount facilities, which were more secure. There was in fact good reason for this. Technically, a bank must be able to predict the shortfall in its clearing account (as a result of known, abnor-mally large, cash outflows) in order to be able to request access to the discount facility. But in the face of mass deposit withdrawals triggered by panic, it will only discover the actual shortage from the daily clearing process. By contrast, the overdraft facility can be provided automatically, since the banks do not have to submit an official proposal to use it. As already noted, rapid response is very important during crises, and this was the simplest and quickest procedure for helping banks—and thus averting the collapse of the national payments system. Liquidity support provided in this way does have the disadvantage that the facility is unsecured, but BI and the government continued to believe that the cri-sis would be of short duration. (Indeed, the president’s instruction, in response to the first daily report on movement of the exchange rate after the float, was to maintain the float for 2–3 weeks, which seemed to demonstrate his own expecta-tion that the crisis would soon be over.) When it lasted longer than expected, BI abandoned the overdraft facility in favour of a longer-term discount facility, as well as using market debt instruments, both of which were more secure.

Providing liquidity support through the clearing mechanism has been very costly, but the fact that at one point there were more than 160 banks receiving liq-uidity support, while only about one-third of these ultimately became problem-atic, implies that the rest complied with the rules. The very high interbank rates on different occasions also showed that some banks did not resort to liquidity support, but were able to meet their liquidity needs through the market process. Finally, many banks, including some that received huge amounts of support, as well as the national payments system itself, survived Indonesia’s worst financial crisis. Whether this justifies the liquidity support policy, time will tell.

Another valid question, raised in BPK’s investigative audit, is why BI contin-ued to provide liquidity support to banks that violated the rules on the use of these funds. The explanation for this is that BI only learned through its supervi-sory practices whether the funds had been used in accordance with these rules, and this involved significant lags. Supervision was conducted through analysis of reports submitted by banks (off-site supervision), and through inspection

its to their offices (on-site supervision). Before the crisis, owing to a shortage of bank supervisors (there were around 1,100 bank supervisors for 238 banks with several thousand branches in total), banks were inspected once every 18 months on average. Even the more up-to-date supervision based on reports submitted by banks involved delays.

In short, with weak banking supervision, and with monitoring subject to con-siderable delays in a fast changing environment, violations in the use of liquidity support were both possible and difficult to detect. Obtaining a clear picture of whether there were indeed violations—and possibly criminal actions—in both the provision and the use of liquidity support depends on whether the fund flows relating to liquidity support can be traced.

LIQUIDITY SUPPORT AND

GOVERNMENT RECAPITALISATION BONDS

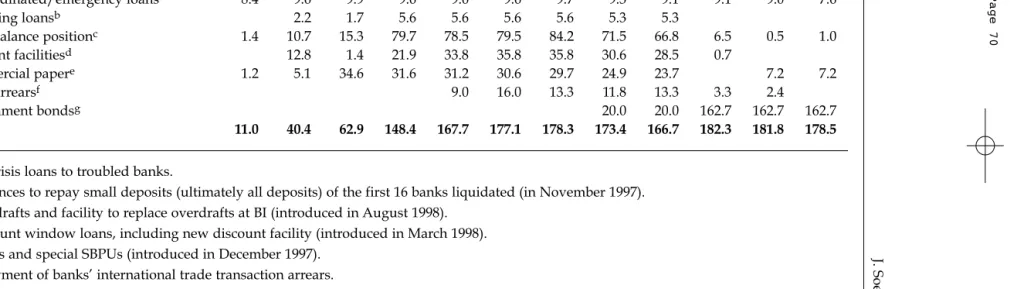

As Dr Dradjad Wibowo has noted, increases in the size of the negative balance of banks with BI seem to be associated with the government’s various steps in addressing the crisis (Wibowo 2002). Greater forbearance towards banks with negative balances seemed to follow the float of the rupiah in August 1997, the clo-sure of the first 16 banks in November 1997, the introduction of the blanket guar-antee and the transfer of authority over problem banks to IBRA in January 1998, and the riots that precipitated Soeharto’s resignation in May 1998. All these steps were associated with heightening uncertainty in the market, which seemed to lead to a ‘flight to safety’ and bank runs. The commercial banks’ aggregate nega-tive balance (overdraft) with BI increased from just Rp 1.4 trillion in July 1997 to Rp 15.3 trillion by the end of 1997, and to Rp 79.7 trillion by May 1998 (table 1). It remained at this level through much of 1998, despite BI’s efforts to replace this liquidity facility with other, more secure instruments, and to cease allowing banks to run negative balances. Indeed, this is the essence of a systemic bank run. BI could not prevent people who were losing confidence in the banking system from withdrawing their funds—to spend on goods and services, to shift to banks perceived to be safe, or to transfer abroad.

The gross cost to the government of financial support provided to the banks is very high (although some part of this cost will be recouped, to the extent that IBRA is successful in recovering loans in default and in seizing assets pledged to it by banks and their owners). From 1996 to 1999, the total amount of liquidity support given to some 164 banks amounted to Rp 179 trillion (table 1), while the amount of government bonds issued for bank recapitalisation amounted to Rp 431 trillion. The total of these two components is close to 50% of GDP—higher than corresponding figures for banking crises in Chile (1981, 43%), Uruguay (1981, 32%), Japan (1992, 22%), Venezuela (1994, 25%), Thailand (1997, 35%), South Korea (1997, 28%) or Malaysia (1997, 18%) (Rojas-Suarez 2002).

RESOLVING PROBLEMS OF LIQUIDITY SUPPORT

In its investigative audit, the Supreme Audit Agency found that liquidity support to the banking sector from 1996 to January 1999 amounted to Rp 144.5 trillion. The audit report claimed that because of deviations in the channelling of funds

70

J. Soedradjad Djiwandono

TABLE 1 Liquidity Support to Banks from Bank Indonesia and Government (selected dates, Rp trillion)

Jul-97 Nov-97 Dec-97 May-98 Jun-98 Jul-98 Aug-98 Dec-98 Jan-99 Feb-99 Apr-99 Dec-99

Extended lending 8.4 11.8 11.6 15.2 15.2 15.2 15.3 14.6 14.4 9.1 9.0 7.6

Subordinated/emergency loansa 8.4 9.6 9.9 9.6 9.6 9.6 9.7 9.3 9.1 9.1 9.0 7.6

Bridging loansb 2.2 1.7 5.6 5.6 5.6 5.6 5.3 5.3

Debit balance positionc 1.4 10.7 15.3 79.7 78.5 79.5 84.2 71.5 66.8 6.5 0.5 1.0

Discount facilitiesd 12.8 1.4 21.9 33.8 35.8 35.8 30.6 28.5 0.7

Commercial papere 1.2 5.1 34.6 31.6 31.2 30.6 29.7 24.9 23.7 7.2 7.2

Trade arrearsf 9.0 16.0 13.3 11.8 13.3 3.3 2.4

Government bondsg 20.0 20.0 162.7 162.7 162.7

Total 11.0 40.4 62.9 148.4 167.7 177.1 178.3 173.4 166.7 182.3 181.8 178.5

aPre-crisis loans to troubled banks.

bAdvances to repay small deposits (ultimately all deposits) of the first 16 banks liquidated (in November 1997).

cOverdrafts and facility to replace overdrafts at BI (introduced in August 1998).

dDiscount window loans, including new discount facility (introduced in March 1998).

eSBPUs and special SBPUs (introduced in December 1997).

fRepayment of banks’ international trade transaction arrears.

gBonds issued to BI by the government in exchange for most of BI’s liquidity support claims on the banks.

Source: Adapted from Indonesia: Statistical Appendix, IMF Staff Country Report 00/133, October 2000: table 30.

0

4

2

5

/

2

/

0

4

4

:

1

6

P

M

P

a

g

e

7

by the central bank and their use by recipient banks, the government might suf-fer losses of Rp 138.4 trillion, 95.7% of the total amount provided to the banking sector throughout this period.

BI raised a number of concerns about the nature, procedures and findings of this audit, the most crucial of which were as follows:

• The audit was more in the nature of a compliance audit than an investigative audit, since it focused largely on whether central bank actions were generally in compliance with existing rules and regulations. But the rules and regula-tions were set up for normal condiregula-tions, while the facilities in question were provided in conditions of crisis. The prevailing economic and financial condi-tions that compelled BI to provide liquidity support were completely ignored in the audit.

• The audit did not take into consideration the function and authority of the cen-tral bank in conducting monetary and banking policy, and no consideration was given to whether the provision of liquidity support was outside the juris-diction of BI, or whether it was a misuse of the central bank’s authority. • The policy of not excluding banks with negative balances from participating in

the clearing during an emergency was in accordance with the Central Bank Law of 1968 and with the government’s then policies of assisting banks with liquidity shortages and of not liquidating banks.

BI raised various other concerns relating to the findings of the audit. For exam-ple, the audit report argued that BI’s advance for repayment of deposits at the liq-uidated banks was a deviation from the rules for bank liquidation. The government regulation on bank closures stipulates that payments to deposit holders should be financed through the sale of assets of the liquidated banks (GOI 1996), so BI could not ask the government to bear this burden. However, this ignores the fact that the decision to liquidate banks was a government decision, and that the government promised to bear the burden of repaying small deposi-tors. This was confirmed in a letter dated 20 February 1998 from the finance min-ister to me as BI governor.

In BI’s view, the liquidity support problem had been dealt with legally through the Master Settlement and Acquisition Agreements (MSAAs), the Master Re-financing and Note Issuance Agreements (MRNIAs), and other agreements between IBRA and bank owners regarding the repayment of what they owed to the government through their use of the support they had received.9The MSAAs

and MRNIAs are agreements between IBRA and the principal owners of private sector banks that received large amounts of liquidity support, some of which had seriously violated the legal lending limit regulations. Under the MSAAs, IBRA acquired ownership of certain of these owners’ assets. By contrast, the MRNIAs are agreements under which the owners pledged, but did not surrender owner-ship of, assets to back up their personal guarantee of repayment of the liquidity support. MRNIAs were used to secure repayment of liquidity support by certain problem banks with which the government was unable to negotiate the acquisi-tion of sufficient assets to cover their BLBI liabilities.

In November 2000 the Parliamentary Working Committee on BLBI reviewed the issues raised by BPK in its investigative audit of BI, and came to a number of conclusions, including the following:10

• BI’s liquidity support reflected a policy decision by the government taken on 3 September 1997 in the face of the crisis.

• Since this policy was intended to address the crisis it was not based on rules and regulations that apply under normal conditions.

• Resolution of the liquidity support problem should aim to hasten recovery of the real sector and minimise the loss to the government. Therefore the solution that relied on the MSAAs and MRNIAs was acceptable.

• The liquidity support problem should be resolved in such a way as to minimise the cost to the government budget, with bonds held by BI and recapitalised banks being redeemed as soon as possible.

Parliament asked the government and the central bank to work together in seeking a solution to the problem, with a view to minimising the budgetary costs and resolving where financial responsibility for the liquidity support policy lay. To these ends the government formed a working team comprising the coordinat-ing minister for economics and finance, the minister of finance, the governor of BI and the attorney general.

On 17 November 2000 the government and BI released a document entitled ‘Basic Agreements between the Government and BI’, which included the follow-ing points:

• The government and BI agreed that liquidity support had been provided by the central bank in order to save the monetary and banking system, as well as the national economy, from collapse.

• The cost of liquidity support would be shared between the government and BI, with a view to minimising costs to the budget. IBRA would make concerted efforts to maximise asset recovery, while BI would bear part of the costs, to the extent its own financial condition allowed.

• Taking its financial condition into consideration, BI agreed to bear Rp 24.5 tril-lion of the total cost.

However, when the Megawati Sukarnoputri government took office in July 2001, the appropriateness of this agreement on burden sharing came into ques-tion. An independent team comprising several Indonesian and international experts (among them Paul Volcker, the US Federal Reserve chair during the Rea-gan administration) was formed and asked to recommend a suitable resolution. On the issue of burden sharing between the government and BI, the team pro-posed that the promissory notes that the government had issued to BI should be viewed as capital support and maintenance for BI. Such support would reflect the government’s ultimate responsibility to maintain the financial strength of its cen-tral bank. To make this support transparent, the existing interest-bearing promis-sory notes should be replaced by a special issue of perpetual zero interest capital maintenance notes (CMNs). The team’s recommendation seemed to be acceptable to the government and BI (GOI 2002).11

FINAL COMMENTS

It is my conjecture that lack of transparency and the serious problem of weak gov-ernance, together with public misunderstanding of, and misinformation about, the operations of banks and the central bank, have prevented the public from acquiring an accurate perspective on these complex issues. Since the credibility of government institutions and officials, including the central bank, had generally been weak in the past, it was inconceivable to many members of the public that support of the commercial banks involving trillions of rupiah could be under-taken in the absence of kickbacks. Sadly, this difficult issue lingers on, without any clear prospect for its resolution. In such circumstances, straight and clean officials can be accused and found guilty of corruption, even in the absence of evi-dence to support such accusations. The champions of justice in their fight against corruption have tended to overlook the plight of such officials, forgetting that a corrupt legal system (widely defined) can be used not only to protect wrongdoers but also to attack the innocent.

NOTES

* Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Indonesia; Senior Visiting Fellow, Insti-tute of Defence and Strategic Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; and former governor of Bank Indonesia. A longer version of this paper appeared as Working Paper No. 40 of the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, Nanyang Tech-nological University, Singapore.

1 I presented my account of the Indonesian crisis in Djiwandono (2001). An updated English version of the book, entitled BI and the Crisis: An Insider’s View, is currently in preparation.

2 BI had earlier invited the IMF to assist it in preparing a comprehensive study of bank restructuring. The study was conducted by staff of the Fund and BI under the leader-ship of Hassanali Mehran, and was published as a report in 1994 (Mehran et al.1994). 3 A government decree on bank liquidation was ultimately issued towards the end of

1996 (GOI 1996).

4 Public sector entities such as Bulog and Pertamina (the state oil company) were in need of foreign exchange, and this need was met through market transactions by BI. Thus the float was never a pure float; indeed, at various times the Monetary Board (which at that time consisted of the finance minister, the coordinating minister for the econ-omy and finance, the minister for industry and trade and the governor of BI) felt that the depreciation was too fast, and it was decided that BI should sell dollars to slow it down.

5 The compulsory shifting of state enterprise bank deposits into SBIs was an approach that had come to be known as a ‘Sumarlin shock’, in reference to the finance minister who had used this approach in the 1980s and early 1990s (Cole and Slade 1996: 53). 6 BI Circular SE 22/227/UPG of 31/3/90.

7 In the corporate debt restructuring program initiated in June 1998, an agreement was reached between international banks, as creditors to Indonesian corporations, and the steering committee representing those corporations, to set up a scheme for voluntary debt restructuring. The so-called Frankfurt Agreement included a government guaran-tee of Indonesian banks’ borrowings from international banks as a condition for the resumption of the international banks’ trade financing facilities and interbank debt exchange offers. BI made an advance to pay these arrears, on the understanding that the cost would be borne by the government.

8 ‘Prior actions’ are instruments of IMF conditionality. They are steps that the authorities

in a country that is under an IMF program agree to take before IMF management recommends a board decision on the use of IMF resources—approving a program or completing a review and/or granting a waiver (IMF 2001: 16).

9 In January 2003 the government announced a release and discharge from criminal prosecution for owners of problem banks, followed shortly thereafter by its decision to raise fuel prices and telephone charges. The release and discharge policy was widely seen as absolving bank owners who were corrupt, while the price increases were con-sidered to be unfair to the public; the result was days of demonstrations.

10 The conclusions of the Working Committee on BLBI were confirmed by Commission IX of the parliament (which oversees the work of BI and the Department of Finance) on 3 July 2003.

11 For an analysis of the economic implications of these arrangements, see Alisjahbana and Manning (2002: 291).

REFERENCES

Alisjahbana, Armida S., and Chris Manning (2002), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bul-letin of Indonesian Economic Studies38 (3): 277–305.

Anonymous (1997), Konspirasi Menggoyang Soeharto: Kumpulan Selebaran Paling Aktual [Conspiracy to Shake up Soeharto: A Collection of Up-to-Date Papers] (mimeo), November.

Ashari, Asnar (2002), ‘Krisis Argentina dan Refleksi Masalah BLBI [The Argentine Crisis and Reflections on the Problem of BI Liquidity Support]’, Kompas, 29 July.

BI (Bank Indonesia) (1999), Annual Report 1999, Jakarta.

BI (2002), Mengurai Benang Kusut BLBI [Untying the Knots of BI Liquidity Support], Jakarta (mimeo).

BPK (Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan) (2000), ‘Special Audit Report on the Provision and Usage of BI Liquidity Support’, Press release of the Supreme Audit Agency, 4 August. Cole, David C., and Betty F. Slade (1996), Building a Modern Financial System: The Indonesian

Experience, Cambridge University Press, New York NY.

Djiwandono, J. Soedradjad (2001), Mengelola BI dalam Masa Krisis [Managing BI in Crisis], LP3ES, Jakarta.

DPR (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat) (2000), Laporan Panitia Kerja Komisi IX Dewan Perwa-kilan Rakyat Republik Indonesia Mengenai Bantuan Likuiditas Bank Indonesia, [Report of the Working Committee of Commission IX of the Indonesian House of Rep-resentatives on Bank Indonesia Liquidity Support], Jakarta, 6 March (mimeo).

Fane, George, and Ross H. McLeod (2002), ‘Banking Collapse and Restructuring in Indo-nesia, 1997–2001’, Cato Journal22 (2): 277–95.

GOI (Government of Indonesia) (1996), Government Decree No. 68, 1996, on Bank Liqui-dation, December.

GOI (1997a), ‘President’s Instructions and Decisions in the Cabinet Meeting on Economics and Finance, Development Supervision, Production and Distribution’, Bina Graha, Jakarta, 3 September.

GOI (1997b), Indonesia: Letter of Intent and Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies, 31 October, available at: http://www.imf.org/external/np/loi/103197.htm. GOI (1998), Indonesia: Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies, Jakarta, 15

Jan-uary, available at: http://www.imf.org/external/np/loi/011598.htm.

GOI (2002), Indonesia: Letter of Intent, Jakarta, 11 June, available at: http://www.imf.org/ external/np/loi/2002/idn/01/index.htm.

IMF (2001), ‘Conditionality in Fund-Supported Programs—Policy Issues’, IMF, Washing-ton DC.

Lindblad, J. Thomas (1997), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Eco-nomic Studies33 (3): 3–33.

MacIntyre, Andrew, and Sjahrir (1993), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 29 (1): 5–33.

Mehran, Hassanali, Robert C. Effros, Gillian Garcia, Olivier Frécaut and Harrison Young (1994), Indonesia: Bank Liquidation and Resolution, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC (mimeo).

Mongid, Abdul (2002), ‘Menelaah Kebijakan Penjaminan dan BLBI [Analysing the Guar-antee Policy and BI Liquidity Support]’, Media Indonesia, 24 September.

Mussa, Michael (2002), ‘Argentina and the Fund: From Triumph to Tragedy’, Institute for International Economics, Washington DC, July.

Rojas-Suarez, Liliana (2002), ‘Proper Sequencing of Financial Market Liberalization: Learn-ing from the Chilean Experience’, Asian Policy Forum on SequencLearn-ing Domestic and External Financial Liberalization, Shanghai, Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo, February.

Sheng, Andrew (1998), The Crisis of Money in the 21st Century, Guest Lecture, City Uni-versity of Hong Kong (mimeo).

Sukowaluyo Mintorahardjo (2001), BLBI Simalakama [The Dilemma of Bank Indonesia Liq-uidity Support], Riset Ekonomi Sosial Indonesia (RESI), Jakarta.

Wibowo, Dradjad (2002), ‘BLBI Sebagai Sebuah Kebijakan [BI Liquidity Support as a Policy]’,Kompas, 9 September.