Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:57

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Perceptions of Compressed Video Distance

Learning (DL) Across Location and Levels of

Instruction in Business Courses

Constance R. Campbell

To cite this article: Constance R. Campbell (2006) Perceptions of Compressed Video Distance Learning (DL) Across Location and Levels of Instruction in Business Courses, Journal of Education for Business, 81:3, 170-174, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.3.170-174

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.3.170-174

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 12

View related articles

ABSTRACT. In this article, the authors

compared student perceptions about

dis-tance learning (DL) across location, type of

business course, and level of instruction.

Results indicated that there were no

differ-ences in student perceptions based on type

of course or level of instruction. Onsite

students found the DL classroom more

dis-tracting than did remote location students,

and the lack of alternative course delivery

formats was more relevant to remote than

to onsite students. All students were more

satisfied than dissatisfied with the DL

experience.

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

t is difficult to envision future univer-sities being completely virtual (Dator, 1998; Dunn, 2000), but distance learning (DL) is a rapidly increasing phenomenon at the college level. The term DL has been used to represent a variety of deliv-ery formats, including correspondence courses, Internet-based courses, interac-tive videos, television, compressed video, cable television, and satellite broadcast-ing (Chadwick, 1995; Potashnik & Cap-per, 1998; Rungtusanatham, Ellram, Siferd, & Salik, 2004).

Despite the increased use of online virtual course delivery systems (Rung-tusanatham et al., 2004), compressed video DL continues to be a popular form of course delivery. Compressed video enables an instructor to interact with geographically separated students, merging the students into one virtual classroom (Plagemann & Goebel, 1999). Debate about the effectiveness of this delivery method continues (Vamosi, Pierce, & Slotkin, 2004), per-haps because there are still relatively few evaluations of its effectiveness.

The primary area of concern about DL is its pedagogical quality (Li, 2005). Of the published studies concerning the quality of DL classes, many considered only one course, thereby limiting the generalizability of the results. In addi-tion, some examinations of DL have focused on graduate courses, whereas others have focused on undergraduate

instruction, but comparisons have not been made across levels of instruction. A second major area of concern about DL is its cost-effectiveness (Fornaciari, Forte, & Mathews, 1999; Hawkes & Cambre, 2000), but there are currently few evalua-tions of this issue (Selim, 2005). The pur-pose of this study was to explore the ped-agogical quality and cost effectiveness of DL, comparing across classes within the business discipline, across onsite and remote locations, and across graduate and undergraduate courses.

Literature Review

A unique feature of DL is the two groups of students involved in the course, those onsite and those viewing the class-room through interactive television at a remote site. Although all of these stu-dents experience the same course, it is unlikely that their experience of the course is the same, raising the issue of comparability of the quality of instruc-tion at the onsite and remote locainstruc-tions.

Pedagogical Quality

One means of assessing the quality of instruction has been to compare onsite and remote students’ performances. For example, using pre- and post-test mea-sures, Magiera (1994) found no differ-ences in learning. Likewise, Umble, Cervero, Yang, and Atkinson (2000) found no significant differences in

learn-Perceptions of Compressed Video

Distance Learning (DL) Across Location

and Levels of Instruction in Business

Courses

CONSTANCE R. CAMPBELL CATHY OWENS SWIFT

GEORGIA SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY STATESBORO, GEORGIA

I

ing between traditional and DL classes in a course on vaccine-preventable diseases. In both instances, though, only one class comprised the study sample.

Others have used grades as a measure of learning locations, with mixed results. Researchers have reported grades for stu-dents at the remote location that were either comparable to or higher than grades of onsite students (Knight & Zhai, 1996). However, these results were often obtained when studying varied disci-plines. Within the business field, Knight and Zhai found significant differences in remote and onsite students’ grades in 14% of the courses studied, eight of which were business courses.

Another approach to comparing quali-ty of instruction at onsite and remote locations is to examine students’ percep-tions of their DL experience. Several fac-tors, including technology, influence stu-dents’ perceptions of DL, not only for its presence, but also for its quality and reli-ability (Plagemann & Goebel, 1999). In a report of a DL experience, Crow, Cheek, and Hartman (2003) noted that technical difficulties were a key contributor to the lack of success in their DL courses. Like-wise, Magiera (1994) found that the need to press a microphone button to speak at remote locations inhibited student partic-ipation. Atkinson (1999) similarly report-ed that the limitations in technology in the DL environment had a greater impact on remote students than on onsite stu-dents. Based on this information, it appears that technology is a key factor in the DL environment and that its impact is greater for remote students as compared with onsite students. The technology issue has not been examined using only business courses nor has it been exam-ined across levels of instruction. Thus, we developed the following hypotheses:

H1: DL technology will be more dis-tracting to remote than to onsite students;

H1a: There will be no difference in the reported level of distraction by technolo-gy among types of business classes; and

H1b: There will be no difference in the reported level of distraction by technolo-gy between undergraduate and graduate students.

The physical presence of the instruc-tor is also a facinstruc-tor in DL. Freddolino

(1996) found that onsite and remote stu-dents had similar perceptions of DL, except in the area of relationships. On the basis of this information, we expect-ed the absence of the professor to be a greater issue at remote locations than at onsite locations. Once again, there was no information on which to base predic-tions of differences across types of classes or levels of instruction. Our hypotheses were as follows:

H2: Remote DL students will be more likely to agree that the physical absence of the instructor affected their learning in the course;

H2a: There will be no difference in the impact of the physical absence of the instructor among types of business classes; and

H2b: There will be no difference in the impact of the physical absence of the instructor between undergraduate and graduate students.

Student satisfaction with DL has been a concern, but results of satisfaction stud-ies have been mixed. Vamosi et al. (2004) discovered that all students perceived that DL hindered their learning of course material and made the course less inter-esting to them, decreasing their motiva-tion in the course; however, they did not compare onsite and remote locations and only used one class as a measure. Like-wise, Ponzurick, France, and Logar (2000) found students to be least satisfied with the DL delivery method, compared with other course delivery formats. In contrast, comparing DL with traditional classroom instruction, Knight and Zhai (1996) found that students were satisfied with their DL experience. Freddolino (1996) found no difference between onsite and remote students’ overall per-ceptions of the DL course. On the basis of these mixed results, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H3: There will be no difference between onsite and remote students in their satisfaction with the DL experience;

H3a: There will be no difference among students in various business classes in their satisfaction with the DL experience; and

H3b: There will be no difference between graduate and undergraduate stu-dents in their satisfaction with the DL experience.

Cost-Effectiveness

There are few publications regarding the cost-effectiveness of DL. Hawkes and Cambre (2000) list 12 nontradi-tional measures of cost-effectiveness for DL, among which are the extent to which DL (a) provides opportunities for students to participate in courses, (b) results in an increase in the number of students participating, and (c) helps “sell the school” to prospective stu-dents.

These measures reflect changes in the demographic characteristics of potential college students. Currently, there is a group of potential students who wish to continue their education, but who are unable to focus exclusively on a full-time educational program that is loca-tion-specific (Freddolino, 1996). For these students, the accessibility of the course is a primary determinant of their participation (Vamosi et al., 2004). These students are likely to elect DL classes because of the convenience they offer, not because they are the preferred method of delivery (Ponzurick et al., 2000; Vamosi et al.). These findings suggest a difference between remote and onsite students in terms of the alter-natives available to them. Therefore, we formed the following hypothesis:

H4: The lack of alternatives to DL will be more important to remote students.

METHOD

Setting

We collected data from DL courses offered through interactive television and satellite broadcast, originating from a comprehensive public university. Instructors presented course material primarily from the onsite location with the capability for all participants to interact. The professor was generally present onsite, with occasional visits to remote locations. Therefore, all students had experience with the professor being present and absent from their locations.

Business DL courses originate from a DL classroom with four large screen televisions—two in the front of the room and two in the back. On the front screens, DL students view themselves on one screen and the remote

tion(s) on the other. In the back of the room, instructors view themselves on one screen and the remote location(s) on the other. Information is transmitted by compressed digital video system. Available for the instructor’s use are an Elmo (which projects an image of a sheet of paper in a manner similar to that of an overhead projector), white-board, computer, and video player. A facilitator in the room assists in mov-ing between technologies and ensures that the camera follows the instructor’s movements. Remote locations also have up to four large-screen televisions as well as computer equipment, dry erase board, and a technical facilitator. At all locations, students must press a button on a microphone and speak into the microphone when making com-ments or asking questions.

Survey

At the end of each semester, students completed a Distance Learning Survey (see Appendix) that was developed by the participating university for use as their student rating of instruction. Each ques-tion was answered on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Participants

We used a total of 521 surveys in the study: 248 onsite and 273 remote. Most respondents were undergraduate students (61%), with the largest numbers in man-agement courses. To ensure confidential-ity of responses so that professors could

not identify survey respondents, the uni-versity chose not to elicit demographic information, such as gender or race, on the Distance Learning Survey.

Analysis

The location at which the student completed the course (i.e., onsite or remote), the particular type of business course, and the level of the course (undergraduate or graduate) were inde-pendent variables. Question 5 and Question 2 (see Appendix) were used as the dependent variables in a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to ana-lyze the first two hypotheses. To test the remaining hypotheses, we factor ana-lyzed the survey, and we used the result-ing factors in a second MANOVA.

RESULTS

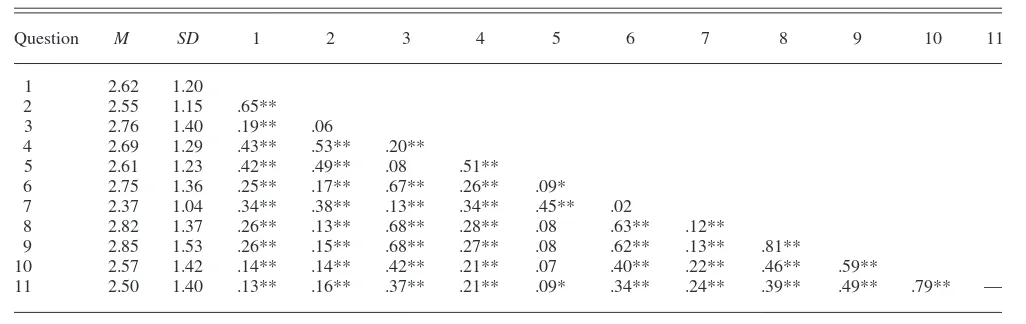

Table 1 shows means, standard devia-tions, and correlations. The test of the first hypothesis, which suggested that remote site students would be more dis-tracted by the DL technology than onsite students would, was significant, but not in the predicted direction, F(1, 490) = 3.09, p < .05. Onsite students were more likely to agree that the tech-nology inhibited their learning than were remote location students. The impact of technology in the DL class-room was not perceived differently depending on which business class was surveyed, F(5, 490) = 1.43, nor upon whether students were undergraduates or graduates,F(1, 490) = .59.

The second hypothesis was not sup-ported. With respect to the impact of the instructor’s presence in the classroom, there was no difference in student rat-ings by location,F(1, 490) = .33. There was also no difference by type of busi-ness class,F(5, 490) = 2.03, or by level of class,F(1, 490) = .34.

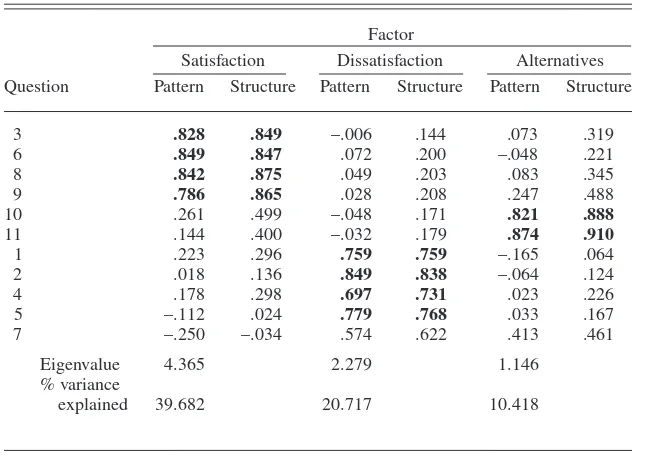

Because there was more than one question pertaining to satisfaction with the course and alternatives to the course, we conducted a principal components factor analysis on the survey, resulting in three factors, which explained 71% of the variance in the data. We also con-ducted an oblique rotation of the data using Direct Oblimin (SPSS, Chicago, IL) to interpret the factors, producing the factor matrices in Table 2. The first factor comprised statements that were worded in favor of DL; therefore, we called this factor Satisfaction. Cron-bach’s alpha reliability of this factor was .89. The second factor consisted of statements about DL that were worded unfavorably; therefore, we called this factor Dissatisfaction (α = .80). The third factor consisted of statements about alternatives to DL. Therefore, we called this factor Alternatives (α= .88).

The MANOVA of the third set of hypotheses indicated that there was no difference in satisfaction or dissatisfac-tion between the onsite and remote loca-tion students, F(1, 478) = .22 and F(1, 478) = 1.15, respectively. Furthermore, there were no differences in students’ reported satisfaction by type of class,

F(5, 478) = 1.57 or by level of class F(1, 478) = .54.

TABLE 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Variables

Question M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

The fourth hypothesis was supported, indicating that the lack of alternatives to DL was more important to students at the remote site than they were to stu-dents onsite,F(1, 478) = 8.59,p < .01. However, there were no differences by type of class, F(5, 478) = 1.26 or by level of class,F(1, 478) = .75.

Because the factor analysis resulted in a factor comprising positive state-ments and a factor comprising negative statements, we conducted a paired ttest to compare the positive and negative statements. The significant result,t(508) = 4.19,p< .01, indicated that students were more likely to agree with the posi-tively worded statements than with the negatively worded ones.

DISCUSSION

Results indicate that compressed video DL continues to be a viable tech-nology. In terms of pedagogical effec-tiveness, students are generally more satisfied than dissatisfied with the DL experience despite the fact that the DL technology is more distracting to onsite than to remote students. The distraction may be explained by the results of the fourth hypothesis test. That is, students who register for DL courses because

they have no other alternatives may be more psychologically prepared for the presence of added technology in the DL classroom.

The lack of significant difference across groups in the impact of the physical absence of the instructor may indicate that this is not an issue for stu-dents. An alternative explanation is that it may indicate that whatever impact the instructor’s absence has on students is uniform across locations, across type of class, and across levels of instruction.

The results also indicate that DL meets several of Hawkes and Cambre’s (2000) cost-effectiveness criteria. DL is effective in providing otherwise unavailable alter-natives for students, thereby providing a means for recruiting new students. DL is providing opportunities for that cohort of students who are unable to physically relocate (Freddolino, 1996). The level of student satisfaction represented in this study also indicates that DL is meeting the cost-effectiveness measure of provid-ing an educational experience with which students are satisfied.

Because of the larger number and variety of student responses included in this study, as compared with prior stud-ies (Crow et al., 2003; Magiera, 1994),

it was possible to explore the issues of types of class and level of instruction, as well as student location. The lack of sig-nificant differences in student percep-tions based on the type of business course and the level of instruction sug-gests that the most important criterion of differentiation in the DL experience is the location of the students.

The results of this study extend our understanding of DL both by confirming findings from previous research as well as by providing new insights specific to this study. In terms of adding to the body of evidence from previous research (e.g., Allen et al., 2004), the current results continue to confirm that instructors need not fear a lack of pedagogical quality in the DL classroom. The results also con-firm that students are generally satisfied with the DL experience.

Several new findings emerged from this study as well. Prior research on DL has generally sampled only one course (Ponzurick et al., 2000; Vamosi et al., 2004). Our sample included multiple courses, but all were within the Busi-ness discipline; thus, we were able to demonstrate that perceptions about DL do not differ across courses within one broad discipline. Prior research also has not compared perceptions regarding DL across levels of instruction. With our sample of undergraduate and graduate classes, we were able to demonstrate that perceptions about DL classes do not vary across level of instruction. Our finding that perceptions of DL did differ by location (i.e., onsite versus remote) is a contribution of this study and indi-cates that onsite students, who are more distracted by the DL technology, may need extra assistance in becoming familiar with the DL setting. A final contribution of the study is the provi-sion of data regarding the fact that remote students are attracted to DL because it provides an opportunity to take courses where no other alternatives are available.

Future studies may build on the cur-rent research by comparing various types of course delivery (i.e., tradition-al onsite, DL, and online). Studies should include undergraduate and graduate classes and several types of business classes in all three environ-ments. In the current survey, we did

TABLE 2. Pattern/Structure Matrix for Factor Analysis of Student Survey Instrument

Factor

Satisfaction Dissatisfaction Alternatives Question Pattern Structure Pattern Structure Pattern Structure

3 .828 .849 –.006 .144 .073 .319

Eigenvalue 4.365 2.279 1.146

% variance

explained 39.682 20.717 10.418

Note. Bold-faced numbers indicate variables included in interpretation of a factor. Satisfaction = statements in favor of distance learning; Dissatisfaction = expressing disfavor with distance-learning; Alternatives = statements related to distance learning alternatives.

not include demographic information; therefore, in future research efforts, investigators should study differences in age levels, gender, full-time versus part-time status, and other variables that may impact student attitudes.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Constance R. Campbell, Associate Professor of Management, Georgia Southern Uni-versity, PO Box 8154, COBA, Statesboro, GA 30460. E-mail: ccampbell@georgiasouthern.edu

REFERENCES

Allen, M., Mabry, E., Mattrey, M., Bourhis, J., Titsworth, S., & Burrell, N. (2004). Evaluating the effectiveness of distance learning: A com-parison using meta-analysis. Journal of Com-munication,54(3), 402–420.

Atkinson, T. R., Jr. (1999). Toward an understand-ing of instructor–student interactions: A study of videoconferencing in the postsecondary dis-tance learning classroom (doctoral dissertation, Louisiana State University and Agricultural Mechanical College, 1999). Digital Abstracts International,60/04, 1035.

Chadwick, J. (1995). Education today: How learn-ing is aided by technology. Link-up, 12(2), 30–31.

Crow, S. M., Cheek, R. G., & Hartman, S. J. (2003). Anatomy of a train wreck: A case study in the distance learning of strategic manage-ment. International Journal of Management,

230(3), 335–341.

Dator, J. (1998). The futures of universities.

Futures 30(7), 615–623.

Dunn, S. L. (2000). The virtualizing of education.

The Futurist, 34(2), 34–38.

Freddolino, P. P. (1996). The importance of rela-tionships for a quality learning environment in interactive TV classrooms. Journal of Educa-tion for Business, 71, 205–209.

Fornaciari, C. J., Forte, M., & Mathews, C. S. (1999). Distance education as strategy: How can your school compete? Journal of

Manage-ment Education, 23(6), 703–719.

Hawkes, M., & Cambre, M. (2000). The cost fac-tor. T.H.E. Journal, 28(1), 26–31.

Knight, W. E., & Zhai, M. (1996). Distance learn-ing: Its effect on student achievement and fac-ulty and student perceptions. Statesboro: Office of Planning & Analysis, Georgia South-ern University.

Li, L. (2005). Reaching out to the world: Devel-oping and delivering higher education pro-grams through distance education to Asian countries. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 3(1), 1–7.

Magiera, F. T. (1994). Teaching managerial finance through compressed video: An alterna-tive for distance education. Journal of Educa-tion for Business, 69, 273.

Plagemann, T., & Goebel, V. (1999). Analysis of quality-of-service in a wide-area interactive distance learning system. Telecommunication Systems, 11, 139–160.

Ponzurick, T. G., France, K. R., & Logar, C. M. (2000). Delivering graduate marketing educa-tion: An analysis of face-to-face versus distance

education. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(3), 180–187.

Potashnik, M., & Capper, J. (1998). Distance edu-cation: Growth and diversity. Finance and Development, 35(1), 42–46.

Rungtusanatham, M., Ellram, L.M., Siferd, S.P., and Salik, S. (2004). Toward a typology of busi-ness education in the Internet age. Decision Sci-ences, 2(2), 101.

Selim, H. M. (2005). Videoconferencing–mediated instruction: Success model. International Jour-nal of Distance Education Technologies, 3(1), 62–80.

Umble, K. E., Cervero, R. M., Yang, B., & Atkin-son, W. L. (2000). Effects of traditional class-room and distance continuing education: A the-ory-driven evaluation of a vaccine-preventable diseases course. American Journal of Public Health,90(8), 1218–1224.

Vamosi, A. R., Pierce, B. G., & Slotkin, M. H. (2004). Distance learning in an accounting principles course—student satisfaction and per-ceptions of efficacy. Journal of Education for Business, 79, 360–367.

APPENDIX Survey Instrument

Scale: 1 = strongly disagreeto 5 = strongly agree

1. The distance learning classroom impacted the way that I learn. 2. The physical absence of the instructor impacted the way that I learn.

3. I learned as much in the distance learning class environment as I would have in an actual live classroom.

4. The distance learning classroom had more distractions than an actual live classroom would have had.

5. The technology (cameras, microphones, and television monitors) inhibited the way I participated in class.

6. My performance in this class was the same as it would have been in an actual live classroom.

7. My grade in this course was affected by the distance learning format. 8. I enjoyed this distance learning class.

9. I would take another distance learning class.

10. I enrolled in a degree program because it was made accessible by distance learning.

11. I would not be enrolled if this class were not available by distance learning.