Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Modular Experiential Learning for

Business-to-Business Marketing Courses

Kenneth Anselmi & Robert Frankel

To cite this article: Kenneth Anselmi & Robert Frankel (2004) Modular Experiential Learning for Business-to-Business Marketing Courses, Journal of Education for Business, 79:3, 169-175, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.79.3.169-175

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.79.3.169-175

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 23

View related articles

The course of nature is to divide what is united and unite what is divided.

—Goethe

xperiential learning is a process of discovery that simplifies complex situations and provides opportunities for resolution of problem elements. Kolb (1984, p. 38) defined experiential learn-ing as a “process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience.” In this article, we describe an experiential exercise, the Extended Buying Center Game (EBCG), that inte-grates marketing course concepts, theo-ries, and practices; develops skills val-ued by industry; and is adaptive to course design. The game is an extended, modular version of the base role-play-ing game originally developed by Mor-ris (1984). The EBCG promotes active learning by involving students, through role-playing, in the dynamics of organi-zational buying behavior and adaptive selling. Activity and assignment mod-ules in the EBCG are both individual and team based. Although primarily designed for marketing, the EBCG is applicable to other business areas, par-ticularly operations/purchasingand man-agement/negotiations.

Experiential Learning

Experiential learning is recognized widely as a technique that improves the

effectiveness of higher education; it rep-resents a shift from an instruction para-digm to a learning parapara-digm (Barr & Tagg, 1995; Saunders, 1997). Within the instruction paradigm, students are viewed as passive recipients of knowl-edge, as opposed to the active partici-pants that they are seen to be within the learning paradigm (Bobbitt, Inks, Kemp, & Mayo, 2000).

The use of the learning paradigm requires students to apply the concepts, theories, and practices presented in class to real-world situations. This expe-riential extension provides discovery and involvement for students, as they become full partners or collaborators in the learning process and assume respon-sibility for their own decisions (O’Ban-ion, 1997, p. 49). Experiential learning also encourages students to engage in higher-order learning as they

personal-ize content, thus developing a deeper understanding of the material (Ander-son, 1997; Bonwell & Ei(Ander-son, 1991; Dabbour, 1997; Shakarian, 1995).

Marketing education literature encourages the use of experiential tech-niques (Dommeyer, 1986; Graeff, 1997; Titus & Petroshius, 1993; Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991). Recent articles suggest experiential frameworks, tech-niques, and exercises for improving learning in marketing courses (Bobbitt, Inks, Kemp, & Mayo, 2000; Gremler, Hoffman, Keaveney, & Wright, 2000; Hamer, 2000; Petkus, 2000). Bobbitt, Inks, Kemp, and Mayo (2000) suggest-ed that students sometimes conclude their business program without a good understanding of the interrelationships between areas of study, especially with-in the marketwith-ing area. The EBCG focus-es on students’ active participation in organizational buying behavior, buyer-seller relationships, and use of the mar-keting mix to create value.

The movement to experiential learn-ing represents a shift among educators from “teaching marketing to helping students learn marketing” (Lamont & Friedman, 1997, p. 24). An extensive body of literature suggests that instruc-tors allocate too much time to dissemi-nating information and too little time to developing student skills (Chonko, 1993; Lamb, Shipp, & Moncrief, 1995;

Modular Experiential Learning

for Business-to-Business

Marketing Courses

KENNETH ANSELMI ROBERT FRANKEL

East Carolina University University of North Florida

Greenville, North Carolina Jacksonville, Florida

E

ABSTRACT. In this article, the authors present the Extended Buying Center Game (EBCG), an experiential exercise that integrates marketing con-cepts and theory with a strong empha-sis on industry skills and that does so in an adaptive course design format. The focus of the EBCG is on organi-zational buying behavior, buyer-seller interaction, and marketing response. The EBCG structure provides students with cooperative and competitive role-playing opportunities, individual and group written assignments and presen-tations, and verbal skill challenges.

Ursic & Hegstrom, 1985). Problem solving, communication, and interper-sonal skills are valued by employers (Floyd & Gordon, 1998; McMahon, 1996). These skills are an important component of meeting industry “cus-tomer requirements” for educators.

Experiential exercises may develop interpersonal skills as well as communi-cation and problem-solving skills. The exercises promote cooperation and enhance listening and critical thinking skills as students share ideas and listen to the ideas of others. When used as a com-plement to lecture, team exercises can be an effective learning technique (Holter, 1994). The main difficulty in employing experiential exercises, and thus the main hurdle to instructor usage, is developing a project that effectively integrates theo-ry and application in a meaningful way (Bobbitt, Inks, Kemp, & Mayo, 2000).

Overview of Extended Buying Center Game

The Extended Buying Center Game builds on the base game developed by Morris (1984), in which students (typi-cally undergraduate juniors and seniors) participate as managers in a team buy-ing center decision. Students readily grasp the theoretical basisof a buying center as “those individuals who partic-ipate in the purchasing decision and who share the goals and risks arising from the decision” (Hutt & Speh, 2001, p. 73). As active participants in the deci-sion process, students experience appli-cation-based learning in the form of multiple influences within the decision process; complex interactions between individuals; and decision making (i.e., the purchasing problem) that is driven by both individual and organizational goals. Webster and Wind (1972) sug-gested that “organizational buying is problem solving” through which organi-zations resolve the gap between what they have and what they need.

We developed game extensions in which students perform new roles as sales/marketing representatives and par-ticipate in adaptive selling and enhanced buying activities and assign-ments. This integrates a greater number of content areas and enhances the learn-ing experience. Students use tools such

as quantitative vendor analysis and per-ceptual mapping, prepare print adver-tisements and customer proposals, and make presentations.

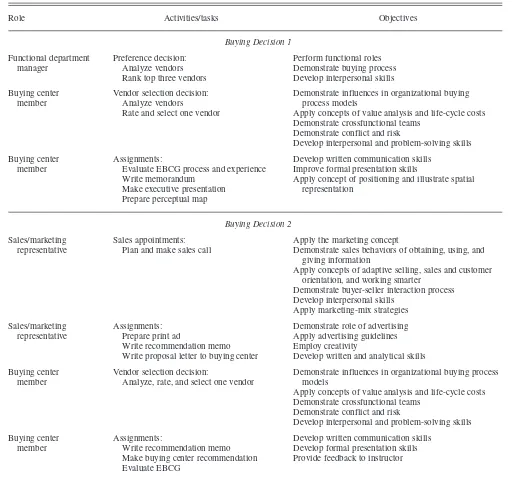

The EBCG follows a learning cycle that integrates Kolb’s (1981, 1984) four learning abilities: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptu-alization, and active experimentation. Concrete experience occurs as students take on a series of roles as departmental managers, buying center members, and vendor representatives. Students inte-grate concepts and communicate their observations and reflections in both writ-ten and verbal assignments and actively experiment in game iterations and buyer-seller decision making. In Table 1, we present roles, activities or tasks, and learning objectives for this exercise.

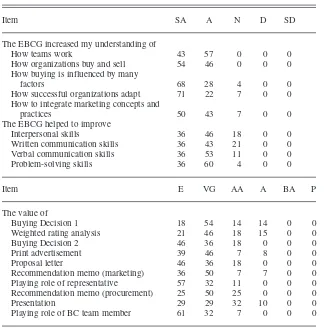

The EBCG divides the complex situ-ation of organizsitu-ational buying and mar-keting response into understandable units or elements. Students learn through involvement and discovery, applying marketing knowledge in a game that they self-report as unique and challenging, creative, fun, inventive, enjoyable, relevant, and important to continue. In Table 2, we show a sample of student evaluations. As indicated, students appreciate and value the EBCG and perceive that the game improves their understanding of business market-ing and the skills necessary for their success. We based our collection of stu-dent feedback on a design by Darian and Coopersmith (2001).

There are two iterations of the EBCG: Buying Decision 1 and Buying Decision 2. In Buying Decision 1, stu-dents become buying center members and make a vendor selection decision. In Buying Decision 2, students take on the additional role of sales/marketing representative. That role creates new information that, when combined with the previous experience of acting as the buying center customer, forms the basis for the second vendor-selection deci-sion. Buying Decision 1 may consume up to four 50-minute class periods, and Buying Decision two up to eight.

In each buying scenario, students deal with forces that influence buying decisions, such as environmental condi-tions (external to the company), organi-zational factors, buying center role

expectations and behavior, and individ-ual personalities. These buying influ-ences, along with the influence of con-flict and negotiation rules, purchase, selling, information, role stress, and decisions, as suggested in the literature (Johnston & Lewin, 1996; Robinson, Faris, & Wind, 1967; Sheth, 1973; Webster & Wind, 1972), are a part of the game scenarios and are created within the game experience.

In making their decisions, students consider the buying situation (e.g., modified rebuy), buying stage (e.g., description of product characteristics needed), and the type of vendor rela-tionship desired. They evaluate seven vendors on criteria that include total dollar value, life cycle costs, vendor experience and reputation, sales sup-port, reciprocity, quality and reject rates, order response time, engineering innovation, size and length of contract, after-sale services, and end-product positioning. Johnston and Lewin (1996) suggested that understanding organiza-tional buying behavior is difficult because the behavior is often a multi-phase, multiperson, multidepartmental, and multiobjective process, but this knowledge is critical for success.

Buying Decision 1

Step 1. Functional Department Vendor Preference

Students participate in a buying situa-tion by performing funcsitua-tional organiza-tional roles, acting as managers in one of seven assigned functional departments: sales and marketing, finance and accounting, purchasing, design and development engineering, quality assur-ance, production, and maintenance. Written position descriptions acquaint students with the primary concerns and responsibilities of their functional roles. Each departmental manager carries equal power in the subsequent crossfunctional buying center decisions, a process that enhances interpersonal skills.

Within each functional department, students must agree on key dimensions or criteria through which to evaluate each of the seven vendors, and they begin the selection process by rank-ordering their top three vendor choices. Written

grounds for each vendor detail attributes that appeal to different functional depart-ments; for instance, the ease of compo-nent installation would be important to the production department. The develop-ment of departdevelop-mental criteria and prefer-ences sets the stage for Step 2.

Step 2. Vendor Selection

The objectives of Step 2 focus on pro-moting student understanding of the multiple influences on the organization-al buying process, vorganization-alue anorganization-alysis, and

life-cycle cost, and how crossfunctional teams resolve conflict and risk via inter-personal problem solving. Buying cen-ters are formed by regrouping randomly selected students from each functional department. A typical class of 35 to 40 students, which would create seven functional departments of five to six stu-dents each, will evolve into five to six buying centers of seven students each. Thus, each buying center represents a multiple-influence, crossfunctional team assigned to resolve a vendor selection (buying) problem. Purchase decisions

are moving more toward team participa-tion (Ellram & Pearson, 1993) and greater diversity and motivation (John-ston & Lewin, 1996).

The task of the buying center is to perform, as a team, an analysis of the potential vendors and then select only one vendor (using the same component scenario as in the departmental prefer-ence decision). A single source deci-sion increases student interaction and thus exposes both departmental and organizational interests. Each buying center creates and implements five

TABLE 1. Extended Buying Center Game Roles, Activities/Tasks, and Learning Objectives

Role Activities/tasks Objectives

Buying Decision 1

Functional department Preference decision: Perform functional roles manager Analyze vendors Demonstrate buying process

Rank top three vendors Develop interpersonal skills

Buying center Vendor selection decision: Demonstrate influences in organizational buying

member Analyze vendors process models

Rate and select one vendor Apply concepts of value analysis and life-cycle costs Demonstrate crossfunctional teams

Demonstrate conflict and risk

Develop interpersonal and problem-solving skills

Buying center Assignments: Develop written communication skills member Evaluate EBCG process and experience Improve formal presentation skills

Write memorandum Apply concept of positioning and illustrate spatial Make executive presentation representation

Prepare perceptual map

Buying Decision 2

Sales/marketing Sales appointments: Apply the marketing concept

representative Plan and make sales call Demonstrate sales behaviors of obtaining, using, and giving information

Apply concepts of adaptive selling, sales and customer orientation, and working smarter

Demonstrate buyer-seller interaction process Develop interpersonal skills

Apply marketing-mix strategies

Sales/marketing Assignments: Demonstrate role of advertising representative Prepare print ad Apply advertising guidelines

Write recommendation memo Employ creativity

Write proposal letter to buying center Develop written and analytical skills

Buying center Vendor selection decision: Demonstrate influences in organizational buying process member Analyze, rate, and select one vendor models

Apply concepts of value analysis and life-cycle costs Demonstrate crossfunctional teams

Demonstrate conflict and risk

Develop interpersonal and problem-solving skills

Buying center Assignments: Develop written communication skills member Write recommendation memo Develop formal presentation skills

Make buying center recommendation Provide feedback to instructor Evaluate EBCG

dimensions as choice criteria in its ven-dor selection process.

Vendor selection incentive. Personal influences are an important force in organizational buying behavior. To add this motivational element (and its poten-tial to place individual or departmental goals in conflict with organizational goals) to the buying center decision, we have individual students earn bonus points for a match between the vendor selected by their buying center and the three vendors selected by their function-al department. Points are function-allotted based on the rank order of vendors by the department (e.g., five points if the match is with their department’s first choice, four points with second choice, and three points with third choice).

Weighted rating analysis. Many pro-gressive companies use weighted rating

analyses in vendor evaluations (Giu-nipero & Brewer, 1993). Although buy-ing centers may use both quantitative and qualitative analysis, as well as deci-sion heuristics (e.g., a conjunctive rule that eliminates a vendor if it falls below a given cutoff level), in their selection of a vendor, the weighted rating analysis provides students with a systematic tool for alternative evaluation.

To formalize a quantitative approach to vendor selection, students use work-sheets to perform a weighted rating ven-dor analysis. This process allows stu-dents (as a group) to adjust vendor ratings on each of the five selected dimensions by each dimension’s impor-tance weight.

Step 3. Written Assignments for Buying Decision 1

For this step, students must complete

three written assignments⎯two individ-ually and one as a group.

Individual reflection on Buying Deci-sion 1. For the first, individual assign-ment, students answer a series of ques-tions regarding their experiences in Buying Decision 1. They address the vendor selection process (e.g., dimen-sions selection process), motivation (e.g., functional role), group interaction, and individual behavior (e.g., bonus points). The essay provides students with an opportunity to reflect on and reinforce the knowledge gained in the first buying decision experience while improving their writing skills.

Memo and presentation to procurement executive. The second assignment improves group interaction as well as student memorandum writing, oral communication, and formal presenta-tion skills. Each buying center group writes and submits a vendor recommen-dation memo to a professional procure-ment executive (from outside the class-room). The memo follows an outline that provides a brief directive, identifies what is at issue, the facts considered and assumptions made, and the analyses performed. The buying center group then makes a formal presentation of the recommendation to the outside execu-tive. Finally, the procurement executive evaluates and grades each presentation on problem-solving and presentation skills, providing students with industry-level expectations and feedback.

Perceptual mapping. The objective of this individual assignment is for stu-dents to prepare a perceptual map (using data taken from the weighted ratings analysis tables) and understand its use in the development of marketing strate-gy. Although students use only aver-ages, and the data represent only their buying center, this assignment helps students discover the benefits of visual-ly mapping product positions and assessing vendor positions relative to their ideal point. The assignment also requires students to take the perspective of a marketing manager and answer questions on vendor strategies and tac-tics, given their buying center market knowledge. Students explore more fully

TABLE 2. Student Evaluations of Knowledge and Skills Derived From EBCG and the Value of Its Components (in Percentages)

Item SA A N D SD

The EBCG increased my understanding of

How teams work 43 57 0 0 0

How organizations buy and sell 54 46 0 0 0 How buying is influenced by many

factors 68 28 4 0 0

How successful organizations adapt 71 22 7 0 0 How to integrate marketing concepts and

practices 50 43 7 0 0

The EBCG helped to improve

Interpersonal skills 36 46 18 0 0

Written communication skills 36 43 21 0 0 Verbal communication skills 36 53 11 0 0

Problem-solving skills 36 60 4 0 0

Item E VG AA A BA P

The value of

Buying Decision 1 18 54 14 14 0 0

Weighted rating analysis 21 46 18 15 0 0

Buying Decision 2 46 36 18 0 0 0

Print advertisement 39 46 7 8 0 0

Proposal letter 46 36 18 0 0 0

Recommendation memo (marketing) 36 50 7 7 0 0 Playing role of representative 57 32 11 0 0 0 Recommendation memo (procurement) 25 50 25 0 0 0

Presentation 29 29 32 10 0 0

Playing role of BC team member 61 32 7 0 0 0

Note. Sample size of 28. Students evaluated the EBCG’s imparting of knowledge and skills with the following anchors: SA (strongly agree), A (agree), N (neutral), D (disagree), and SD (strong-ly disagree). They evaluated the value of the EBCG components with the following anchors: E (excellent), VG (very good), AA (above average), A (average), BA (below average), and P (poor).

vendor response and adaptive selling in Buying Decision 2.

Buying Decision 2

In Buying Decision 2, students make a second vendor selection decision using the same component scenario from Deci-sion 1, but this time student participation is expanded to include both sides of the exchange process. Students maintain their original buying center roles but now assume the role of a sales and marketing representative for one of the seven origi-nal vendors (calling on a buying center other than their own). Each buying center determines its own reason, such as the performance of the in-vendor, for mov-ing from a straight rebuy situation to a modified rebuy situation and thus requir-ing sales calls from vendors for Period 2 (e.g., Year 2).

As a sales and marketing representa-tive, each student has three opportuni-ties⎯a sales call, an advertisement, and a proposal (offer) letter⎯to communi-cate with his or her assigned customer buying center. In this seller role, stu-dents perform the basic sales behaviors of obtaining, using, and giving informa-tion (Reid, Pullins, & Plank, 2002), con-sider their orientation to the customer (Saxe & Weitz, 1982), and practice adaptive selling (Spiro & Weitz, 1990; Weitz, Sujan, & Sujan, 1986). Saxe and Weitz suggested that customer-oriented selling is problem solving, or the “prac-tice of the marketing concept at the level of individual and customer.” Adaptive selling is an important part of success (Weitz, 1981), requiring knowledge of sales situations and information acquisi-tion skills (Weitz et al., 1986).

A second vendor decision provides opportunities for active learning on both sides of the exchange process. Students continue their development of interper-sonal and communication skills and apply marketing concepts, theories, and practices in creative problem solving

⎯determining the right strategies and tactics to get the business or respectfully declining to seek it. The use of the sales/marketing representative role in Buying Decision 2 creates new vendor proposals and information. In other words, students become co-creators of the game.

Step 1. Sales/Marketing Representative Role—Vendor Sales Appointment With Buying Center

The vendor sales appointment pro-vides students with a basic understand-ing of the sales side of the buyer-seller interaction process, the marketing con-cepts of customer orientation and adap-tive selling, and the role of pricing in strategy. To accomplish this objective, students must plan and make the sales call. They have an appointment time and window (10 to 15 minutes) to call on their assigned buying center cus-tomer. Although familiar with the buy-ing scenario and process from their pre-vious experience in Buying Decision 1, the students’ challenge is to acquire information (selection criteria) from their assigned buying center customer and make a positive initial impression. Two signature sheets provide for role-playing verification and the assignment of participation points. A variation of this step may be the use of “team” sell-ing, a practice discussed by Moon and Armstrong (1994).

Step 2. Written Sales Assignments

For this step, the student must com-plete three written assignments as the sales and marketing representative; these assignments are individual efforts.

Print advertisement for buying center customer. In their role as a sales/market-ing representative for their assigned ven-dor, students develop a full-page (8.5 x 11) print ad that would appear in an industry trade journal. Information obtained during their sales call appoint-ment and the strategy and tactics that they employ with this account form the foun-dation for the assignment. The print ad assignment provides an opportunity for students to demonstrate the role of adver-tising, develop criteria for an effective print ad, and use creativity and advertis-ing guidelines, such as those found in Lohtia, Johnston, and Aab (1995). Media selection is not part of the assignment but could be a game extension.

Recommendation memo to the director of marketing. The objective of the internal recommendation memo is to improve

students’ analytical and memorandum writing skills. In their role of sales/mar-keting representatives, students write a memo to the (hypothetical) director of marketing of their vendor company. The memo includes the vendor’s current account status (e.g., out-vendor), a situa-tional analysis (e.g., competitive offer-ings), and a course-of-action recommen-dation for the proposal. Students derive their situational analyses from scenario information (e.g., initial vendor offering and background) and the buying center appointment. Issues addressed in the analysis include the organizational buy-ing process, in- or out-vendor strategies, forces that influence the buying process, the value proposition, and account rela-tionship and behavior. Students adapt the initial product or service offering (i.e., bundle of attributes and benefits) accord-ing to buyaccord-ing center/customer require-ments and sound analysis.

Proposal letter to buying center cus-tomer. Using the recommendation memo from the previous assignment as a basis, students further their analytical and writing skills by presenting a pro-posal to their buying center customers. The proposal letter outlines the require-ments for the vendor offer for Period 2. Students may adjust the bundle of attributes and benefits offered from ini-tial scenario information (based on real-istic strategic objectives), within the instructor’s accepted limits. The clarity and appearance of the letter has proved influential in the vendor selection deci-sion of buying centers. The buying cen-ter appointment, recommendations, and proposal provide students with the opportunity to explore the three basic sales behaviors and adapt their offering and communication to the given pur-chase situation. Reid, Pullins, and Plank (2002) discussed this adaptive process for sales success.

Step 3. Buying Center Vendor Selection

In the second buying center vendor decision, students revisit the process of organizational buying. The task for each buying center is to perform a vendor analysis and decide on a single vendor for Period 2 by using new vendor

mation (i.e., print advertisements and proposal letters) and the skills learned in the Buying Decision 1 activities. This time, the buying center members make their vendor decision knowing that they will communicate their choice in a rec-ommendation memo to their vice presi-dent of procurement.

Step 4. Buying Center Assignments for Decision 2

For this step, students must complete three written assignments⎯two group efforts and one individual assignment.

Recommendation memo to the vice president of procurement. To expand student memorandum-writing skills, each buying center communicates its vendor choice and selection rationale in a two-page memo to the vice president of procurement. Students follow a prob-lem-solving format and state the pur-pose of the assignment (e.g., the reason for moving to modified rebuy), identify relevant facts, present their analysis logic, and offer a recommendation.

Buying center presentation to a busi-ness marketing class. Buying centers are required to present an overview of the buying process and tools used to select their vendor and to participate in an oral question-and-answer compo-nent, which helps develop students’ for-mal presentation skills. The assignment helps buying centers reflect on and communicate about the decision processes, answer questions from any or all vendors, and acknowledge the suc-cessful vendor. The presentation pro-vides an opportunity to share as a class, process influences and motivations, and think through experiences.

Individual student evaluation of the EBCG. To provide a formal feedback mechanism to the instructor and to solicit suggestions for future EBCG usage, students respond to scaled ques-tions on the level of increased under-standing and skill improvement result-ing from the EBCG and the value of game components. Open-ended ques-tions provide an opportunity for student suggestions. For questionnaire content, see Table 2.

Discussion

Our purpose in this article has been to present an example of experiential learn-ing applicable to business-to-business marketing, operations, and management courses. The Extended Buying Center Game covers a broad spectrum of topics with the intent of exposing students to a number of basic activities or skill sets— such as problem solving, verbal and writ-ten communications, and interpersonal skills⎯that they are likely to use in an introductory employment setting.

From the students’ learning perspec-tive, the EBCG provides several diverse benefits. First, students confront the reality of the business world and its demands of both competitive and coop-erative behavior from individuals. Stu-dents must work as individuals as well as in groups. Many, if not most, business courses today require group work, though this often excludes the develop-ment of individual responsibility. The EBCG requires individual preparation to strengthen individual student develop-ment and counter any individual’s ten-dency to “free-ride” in a group setting.

Second, the Extended Buying Center Game provides students with a look at both sides of the exchange process; in other words, they see the sales and mar-keting perspective as well as the pur-chasing/sourcing perspective. This dual perspective enables students to see a variety of career opportunities. Third, students develop both written and ver-bal skills. Industry recruiters emphasize that both skills are critically important today, particularly the ability to present and support a position concisely, clear-ly, and accurately.

Finally, the EBCG becomes a part of a student’s portfolio for prospective em-ployment opportunities. In fact, one of the authors uses sales and marketing as-signments as a reference point for student referrals. Barr and McNeilly (2002) sug-gested that these valuable experiences should be communicated to recruiters.

Clearly, the EBCG is a time-consum-ing activity that requires considerable planning on the part of the instructor. Thus, instructors initially may choose to perform only the buying center Deci-sion 1 activities until they feel comfort-able with the game’s format and are

sat-isfied that the game provides the bene-fits that they expect.

NOTE

We gratefully acknowledge the work of Michael H. Morris in developing the base exercise.

REFERENCES

Anderson, E. J. (1997, May). Active learning in the lecture hall. Journal of College Science Teaching, 26, 428−429.

Barr, T. F., & McNeilly, K. M. (2002). The value of students’ classroom experiences from the eyes of the recruiter: Information, implications, and rec-ommendations for marketing educators. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(2), 168−173. Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to

learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate stu-dents. Change, 27(November/December), 12. Bobbitt, L. M., Inks, S. A., Kemp, K. J., & Mayo,

D. T. (2000). Integrating marketing courses to enhance team-based experiential learning. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(1), 15−24. Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learn-ing: Creating excitement in the classroom. Wash-ington, DC: George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development. (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1) Chonko, L. B. (1993). Business school education:

Some thoughts and recommendations. Market-ing Education Review, 3(1), 1−9.

Dabbour, K. S. (1997, July). Applying active learning methods to the design of library instruction for a freshman seminar. College and Research Libraries, 58, 299−308.

Darian, J. C., & Coopersmith, L. (2001). Integrat-ed marketing and operations team projects: Learning the importance of cross-functional cooperation. Journal of Marketing Education, 23(2), 128−135.

Dommeyer, C. J. (1986, Spring). A comparison of the individual proposal and the team project in the marketing research course. Journal of Mar-keting Education, 8, 30−38.

Ellram, L. M., & Pearson, J. N. (1993). The role of the purchasing function: Toward team partic-ipation. International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management, 29(3), 3−9. Floyd, C. J., & Gordon, M. E. (1998, Summer).

What skills are important? A comparison of employer, student, and staff perceptions. Jour-nal of Marketing Education, 20, 103−109. Giunipero, L. C., & Brewer, D. J. (1993, Winter).

Performance-based evaluation systems under total quality management. International Jour-nal of Purchasing and Materials Management, 29,35−41.

Graeff, T. R. (1997, Spring). Bringing reflective learning to the marketing research course: A cooperative learning project using intergroup critique. Journal of Marketing Education, 19, 53−64.

Gremler, D. D., Hoffman, K. D., Keaveney, S. M., & Wright, L. K. (2000). Experiential learning exercises in services marketing courses. Jour-nal of Marketing Education, 22(1), 35−44. Hamer, L. O. (2000). The additive effects of

semi-structured classroom activities on student learn-ing: An application of classroom-based experi-ential learning techniques. Journal of Market-ing Education, 22(1), 25−34.

Holter, N. C. (1994). Team assignments can be effective learning techniques. Journal of Edu-cation for Business, 70(2), 73−76.

Hutt, M. D., & Speh, T. W. (2001). Business mar-keting management: A strategic view of indus-trial and organizational markets. Fort Worth: Harcourt.

Johnston, W. J., & Lewin, J. E. (1996). Organiza-tional buying behavior: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Business Research, 35(1), 1−15.

Kolb, D. A. (1981). Learning styles and discipli-nary differences. In Alan W. Chickering and Associates (Eds.),The modern American col-lege(pp. 37−75). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning:

Experi-ence as the source of learning and develop-ment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Lamb, C. W., Shipp, S. H., & Moncrief, W. C., III

(1995, Summer). Integrating skills and content knowledge in the marketing curriculum. Jour-nal of Marketing Education, 17,10−19. Lamont, L. M., & Friedman, K. (1997, Fall).

Meeting the challenges to undergraduate mar-keting education. Journal of Marmar-keting Educa-tion, 19, 17−30.

Lohtia, R., Johnston, W. J., & Aab, L. (1995). Business-to-business advertising: What are the dimensions of an effective print ad? Industrial Marketing Management, 24(5), 369−378. McMahon, K. (1996, Winter). MBA job search:

Surviving the résumé round file. Marketing Educator,4.

Moon, M. A., & Armstrong, G. M. (1994, Win-ter). Selling teams: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Personal Sell-ing and Sales Management, 14, 17−30. Morris, M. H. (1984). The buying center game:

An experiential approach to developing an industrial marketing orientation. In G. Teeple (Ed.),Proceedings: Atlantic Marketing Associ-ation Conference (pp. 72−77). Orlando: Atlantic Marketing Association.

O’Banion, T. (1997). A learning college for the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Asso-ciation of Community Colleges.

Petkus, E., Jr. (2000). A theoretical and practical framework for service-learning in marketing: Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(1), 64−70.

Reid, D. A., Pullins, E. B., & Plank, R. E. (2002). The impact of purchase situation on salesper-son communication behaviors in business mar-kets. Industrial Marketing Management, 31(3), 205−213.

Robinson, P. J., Faris, C. W., & Wind, Y. (1967). Industrial buying and creative marketing. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Saunders, P. M. (1997, March). Experiential learning, cases and simulations in business communications. Business Communication Quarterly, 60, 97.

Saxe, R., & Weitz, B. A. (1982, August). The SOCO scale: A measure of the customer orien-tation of salespeople. Journal of Marketing Research, 19,343−351.

Shakarian, D. C. (1995, May-June). Active learn-ing strategies that work. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 66, 21−24. Sheth, J. N. (1973, October). A model of industrial

buyer behavior. Journal of Marketing, 37, 50−56. Spiro, R. L., & Weitz, B. A. (1990, February). Adaptive selling: Conceptualization, measure-ment, and nomological validity. Journal of Marketing Research, 27, 61−69.

Titus, P. A., & Petroshius, S. M. (1993, Spring). Bringing consumer behavior to the workbench: An experiential approach. Journal of Marketing Education, 15, 20−30.

Ursic, M., & Hegstrom, C. (1985, Summer). The views of marketing recruiters, alumni, and stu-dents about curriculum and course structure. Journal of Marketing Education, 7, 21−27. Webster, F. E., Jr., & Wind, Y. (1972, April). A

gen-eral model for understanding organizational buy-ing behavior. Journal of Marketbuy-ing, 36, 12−19. Weitz, B. A. (1981). Effectiveness in sales

interac-tions: A contingency framework. Journal of Marketing, 45(1), 85−103.

Weitz, B. A., Sujan, H., & Sujan, M. (1986, October). Knowledge, motivation, and adap-tive behavior: A framework for improving sell-ing effectiveness. Journal of Marketsell-ing, 50, 174−191.

Williams, D. L., Beard, J. D., & Rymer, J. (1991, Summer). Team projects: Achieving their full potential. Journal of Marketing Education, 13, 45−53.