We should all have worms. If we do not, it is because we live in an area with ad-equate sanitation or because we have recently taken an effective treatment. There is abundant archaeological evi-dence that earlier populations of what are now developed countries were just as commonly infected as the popu-lations of the low-income countries of today. Worms were still a common fea-ture of the paediatric wards of major cities in Europe and the USA at the beginning of the 20th century1. Today,

worms remain amongst the most com-mon of all chronic infections of humans, with more than a third of the world’s population infected at any one time1,2.

Having worms also implies a lifelong, intimate association. In endemic areas, children can expect to be infected as soon as they can crawl, and to remain infected and be regularly re-infected for the rest of their lives. During infection, all major worm species undergo a tissue migration, and some maintain perma-nent intracytoplasmic exposure for as

long as they live. Worms are large ani-mals, and are, by several orders of mag-nitude, the largest enteric pathogens of humans. Typical worm burdens produce a million or more eggs per day, accom-panied by equivalently copious amounts of secretory and excretory products.

A recent paper in Immunology Today3

suggests that helminth infections impair the immune response of the host to HIV and TB, and might contribute to the spread of these diseases. The broader context of the impact of worm infections on the human immune re-sponse, and the implications for disease patterns in low-income countries merit exploration.

Worms and Immunoregulation

So, does chronic, life-long exposure to massive amounts of helminth antigen have any generalized immunoregulatory consequences? We know that infection results in potent, highly polarized immune responses characterized by elevated

T-helper cell type 2 (Th2) cytokine and IgE production, eosinophilia and, in some cases, mastocytosis. Although, historically, research in this area has focused on whether or not these responses have consequences for the parasites – an issue that remains largely unresolved – there is now increasing interest in whether they also have an impact on the host by modifying susceptibility to unrelated diseases.

This is not an entirely new question. There has long been an assumption that the atavistic association between humans and worms has evolved into a symbiotic relationship – in some ways, worms are good for you. Indeed, this has been used as an argument against de-worming4. It is suggested that the high

levels of nonspecific IgE and downregu-latory Th2 cytokines induced by worm infection offer some adaptive protection against inflammatory diseases, and this has been cited as a reason for the sup-posedly low incidence of atopic disease in societies where worms are prevalent4.

Comment

Parasitology Today, vol. 16, no. 7, 2000 0169-4758/00/$ – see front matter © 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S0169-4758(00)01689-6 273

Good Worms or Bad Worms:

Do Worm Infections Affect the Epidemiological

Patterns of Other Diseases?

D. Bundy, A. Sher and E. Michael

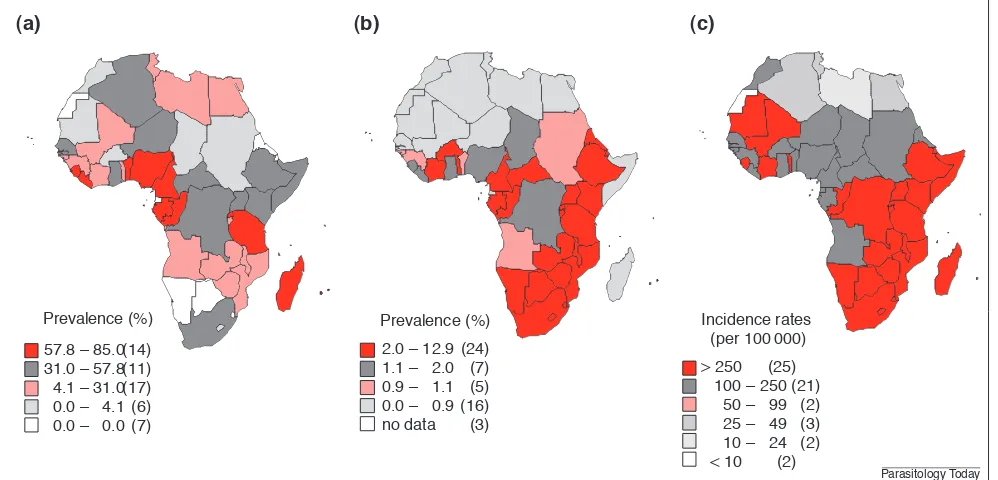

Fig. 1. The distribution of geohelminths2 (Ascariasis, Trichuiriasis and hookworm infections) (a), HIV/AIDS cases14 (b) and TB incidence15(c) in Africa. Note that the prevalence maps for the geohelminths and HIV/AIDS are categorized using standard deviations derived from the data (to enhance comparability), while the TB map is presented as categorized by the WHO. HIV/AIDS prevalence rates were available only for adults (15–49 years old) in the following countries: Algeria, Comoros, Egypt, Eritrea, Libya, Mauritius, Reunion, Somalia, Sudan and Tunisia.

Parasitology Today

Prevalence (%) 57.8 Ð 85.0(14) 31.0 Ð 57.8(11) 4.1 Ð 31.0(17) 0.0 Ð 4.1 (6) 0.0 Ð 0.0 (7)

Prevalence (%) 2.0 Ð 12.9 (24) 1.1 Ð 2.0 (7) 0.9 Ð 1.1 (5) 0.0 Ð 0.9 (16) no data (3)

Incidence rates (per 100000) > 250 (25) 100 Ð 250 (21) 50 Ð 99 (2) 25 Ð 49 (3) 10 Ð 24 (2) < 10 (2)

Comment

274 Parasitology Today, vol. 16, no. 7, 2000

Interestingly, intracellular bacterial and protozoan infections may also protect against allergy and asthma, but in this case, by working in the opposite direc-tion, through their induction of Th1 re-sponses5. That helminths may further

modify host responses by suppressing Th1-mediated immunopathology is sug-gested by preliminary studies in patients in the USA in which (non-patent and self-terminating) infection with worms that do not normally infect humans (Trichuris suum) appears to alleviate the symptoms of inflammatory bowel dis-ease6. These as yet unconfirmed

obser-vations suggest that helminth infection may help to downregulate some allergic and inflammatory conditions. Even with the most optimistic projections, the public health benefit of this interaction is likely to be slight, and is unlikely to out-weigh the substantial developmental consequences of allowing infections to persist throughout childhood.

In contrast to these apparently ben-eficial effects of worm infection, it has also been suggested that the Th2-dom-inant responses make the host more susceptible to other, more clinically im-portant, infections. Several studies have shown that helminths may jeopardize the ability of the host to mount a protective immune response. For exam-ple, schistosome infection in mice en-hances the Th2 response, downregu-lates Th1 cytokines and impairs the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response7–9. This

may explain why Schistosoma mansoni -infected humans have an impaired Th1 response to tetanus toxoid10.

Worms, TB and HIV

These observations suggest that helminth infection modifies the host re-sponses to HIV and TB, and contributes to the spread of these diseases3,11(Fig. 1).

The effect is said to be caused by a com-bination of increased susceptibility, de-creased protection and faster disease progression11. The evidence for such an

effect is drawn from a series of obser-vations: (1) HIV and TB are more com-mon, progression to AIDS more rapid and reactivation of latent TB more frequent in populations where helminths are more prevalent; (2) helminth-infected individuals from these populations exhibit a charac-teristic pattern of immune dysfunction: Th2-skewed responses, enhanced suscep-tibility of blood mononuclear cells, in-creased expression of HIV co-receptors, decreased in vitrosecretion of B chemo-kines; and (3) deworming such individu-als and moving them to materially better living conditions (specifically, the migration

of Ethiopian Jews to Israel) results in changes towards responses more typical of populations of developed countries where helminths are no longer endemic. The limitation of this sort of evidence is that populations in the poorest parts of the world suffer many simultaneous insults to health, and not worm infection alone. Similarly, transferring an individual from a materially poorer to a materially richer community is accompanied by many changes, including improved nutri-tion, in addition to the loss of worms. The evidence and the argument are compelling, but not conclusive. One im-portant test will be whether deworming programmes for populations in situ in Africa have an impact on HIV and TB incidence and progression. Another op-portunity, although perhaps more tech-nically challenging to assess, would be to determine whether currently existing vaccines for TB and other diseases are more effective in communities that have participated in deworming programmes. There is now an opportunity to under-take these experiments as such pro-grammes are being implemented on a substantial scale in many of the poorest parts of Africa, particularly as part of child development strategies1.

Hope-fully, the parasitological research com-munity will grasp this opportunity both to substantiate and to investigate these complex relationships further.

The research community might also recognise that the proposed link be-tween helminthiasis and other infections has important implications for the de-velopment of vaccines against helminths. If such vaccines mimic the Th2-related effects of natural infection, then they might have all the harmful (or beneficial) consequences now attributed to infec-tion itself. However, effective helminth vaccines may promote a Th1 response against primary infection and be com-plementary, perhaps even synergistic, to existing vaccines against childhood ill-nesses. Resolving which of these out-comes is the more likely is essential to the confident promotion of the general use of vaccines against helminths.

Even our current, rather incomplete state of knowledge has positive practical implications. Community control of helminth infection is promoted now be-cause of its safety, simplicity and low cost, and because of its demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing the develop-ment of children12,13. The public health

case for deworming is already well made. If there are additional positive consequences (even probably positive consequences) that include such major benefits as enhancing the protective

response to vaccination and reducing the incidence and progression of HIV and TB, then the case for deworming would be difficult to overstate.

References

1 Bundy, D.A.P. and De Silva, N.R. (1998) Can

we deworm this wormy world? Br. Med. Bull.

54, 421–432

2 The Partnership for Child Development

(1997) This wormy world: Fifty years on.

Parasitol. Today13 (11), PTC 04

3 Bentwich, Z.et al.(1999) Can eradication of

helminthic infections change the face of AIDS and tuberculosis? Immunol. Today20, 485–487

4 Nelson, G. (1992) Ascariasis: indiscriminate or

selective mass chemotherapy? Lancet 339, 1264–1265

5 Lynch, N. et al.(1999) Parasite infections and

the risk of asthma and atopy. Thorax 54, 659–660

6 Shirakawa, T. et al. (1997) The inverse

association between tuberculin responses and atopic disorder. Science275, 77–79

7 Summers, R.et al.(1999) Gastroenterology116,

Abstract No G3592

8 Sher, A.et al. (1992) Role of T-cell derived

cytokines in the downregulation of immune responses in parasitic and retroviral infection.

Immunol. Rev.127, 183–204

9 Actor, J.et al.(1993) Helminth infection results

in decreased virus-specific CD81 cytotoxic T-cell and Th1 cytokine responses as well as delayed virus clearance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.90, 948–52

10Sabin, E.A., et al. (1996) Impairment of

tetanus toxoid-specific Th1-like immune responses in humans infected with

Schistosoma mansoni. J. Infect. Dis. 173, 269–272

11Bentwich, Z.et al.(1995) Immune activation

is a dominant factor in the pathogenesis of African AIDS.Immunol. Today16, 187–191

12WHO (1996) Strengthening interventions to

reduce helminth infections, as an entry point for the development of health promoting schools. WHO/SCHOOL/96.1WHO/HPR/ HEP/96.10 (WHO Information Series on School Health, Document One)

13The Partnership for Child Development,

(1997) Better health, nutrition and education for the school aged child. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91, 1–2

14Joint United Nations Programme on

HIV/AIDS & World Health Organization (1998) Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic.

UNAIDS & WHO

15World Health Organization (1999) Global

Tuberculosis Control. WHO Report 1999.

WHO/TB/99.259

Don Bundyis at the World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433, USA. Alan Sher is at the .Immunobiology Section, Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Building 4, Room 126, National Institutes of Health, 4 Center Drive MSC 0425, Bethesda, MD 20892-0425, USA. Edwin Michael is at The Wellcome Trust Centre for the Epidemiology of Infectious Disease, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, UK OX1 2FY. Tel: +1 202 477 1234, Fax: +1 202 522 3233, e-mail: [email protected]