Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:55

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Role of University Entrepreneurship Programs in

Developing Students’ Entrepreneurial Leadership

Competencies: Perspectives From Malaysian

Undergraduate Students

Afsaneh Bagheri & Zaidatol Akmaliah Lope Pihie

To cite this article: Afsaneh Bagheri & Zaidatol Akmaliah Lope Pihie (2013) Role of

University Entrepreneurship Programs in Developing Students’ Entrepreneurial Leadership Competencies: Perspectives From Malaysian Undergraduate Students, Journal of Education for Business, 88:1, 51-61, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.638681

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.638681

Published online: 19 Nov 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 238

View related articles

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.638681

Role of University Entrepreneurship Programs in

Developing Students’ Entrepreneurial Leadership

Competencies: Perspectives From Malaysian

Undergraduate Students

Afsaneh Bagheri and Zaidatol Akmaliah Lope Pihie

University Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia

The authors aimed to identify the role of university entrepreneurship education programs in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership competencies. A total of 18 interviews were conducted with students and university entrepreneurship program coordinators. From these, 16 prominent roles of the programs emerged and were classified into 2 clusters: student-related and program-related roles. Student-related roles reflect the contributions of the programs in developing personal and interpersonal leadership competencies of students. Program-related roles are the roles that the programs play in organizing and sustaining various entrepreneurial leadership learning opportunities, linking students to the world of entrepreneurial venturing, and having a holistic approach to university entrepreneurship programs.

Keywords: entrepreneurial leadership, entrepreneurship education, Malaysia, university students

Entrepreneurship scholars highlighted entrepreneurship as a means of socioeconomic development in both developed and developing countries (Busenitz et al., 2003; Matlay, 2005, 2006). Entrepreneurship education plays prominent roles in developing entrepreneurial competencies and inten-tions in students (De Pillis & Reardon, 2007; Fayolle, Gailly, & Lassas-Clerc, 2006; Souitaris, Zerbinati, & Al-Laham, 2007; Wilson, Kickul, & Marlino, 2007; Wu & Wu, 2008; Zhao et al., 2005). Accordingly, entrepreneurship develop-ment turned to become one of the top priorities of governdevelop-ment policies (Hannon, 2006; Mitra & Matlay, 2004) and univer-sity missions all over the world (Holmgren et al., 2005). Specifically in Malaysia, all of the public institutions of higher education recently assigned to provide students with entrepreneurship education programs (Jafaar & Abdul Aziz, 2008).

Teaching leadership to students through entrepreneurship education as both academic and cocurricular programs is a recent trend in higher education (Mattare, 2008). In essence, the importance and necessity of developing leadership

Correspondence should be addressed to Afsaneh Bagheri, University Putra Malaysia, Faculty of Educational Studies, Serdang, Selangor 43400, Malaysia. E-mail: bagheri20052010@hotmail.com

competencies among entrepreneurs is one of the most in-fluential factors in a new venture creation process, growth, and success (Baron, 2007; Frey, 2011; Murali, Mohani, & Yuzliani, 2009) has recently been identified by researchers (M. H. Chen, 2007; Kuratko, 2007; Surie & Ashley, 2008). There is little empirical study on contributions of university entrepreneurship programs in students’ entrepreneurial lead-ership learning and development (Okudan & Rzasa, 2006). In addition, there are differences among entrepreneurship scholars on definition of entrepreneurship education and par-ticularly entrepreneurial leadership (Gupta, MacMillan, & Surie, 2004; Hannon, 2006; Heinonen, 2007; Swiercz & Ly-don, 2002), and none of the textbooks used for teaching entrepreneurial leadership focuses on developing the spe-cific leadership competencies required for dealing with the inherited challenges and crises of entrepreneurial venturing (Mattare, 2008; Okudan & Rzasa).

Entrepreneurial leadership has been conceptualized as a process in which individuals have the competencies to de-velop an entrepreneurial vision and mobilize and influence a group of competent and competitive people to realize the vision (Gupta et al., 2004). Entrepreneurial leadership com-petencies can be learned and developed through active in-volvement in higher education (Kempster & Cope, 2010). In contrast to earlier notions of entrepreneurs as an inherent

characteristic (McClelland, 1961; Stewart, Watson, Carland, & Carland, 1998), all students who involve themselves in en-trepreneurship education have the potential to develop their entrepreneurship knowledge and skills (Fuchs, Werner, & Wallau, 2008; Heinonen & Poikkijoki, 2006; Henry, Hill, & Leitch, 2005a; Kuratko, 2007; Peterman & Kennedy, 2003). However, there is not enough knowledge about the roles that entrepreneurship education programs play in developing stu-dents’ entrepreneurial skills (Anderson & Jack, 2008) and, particularly, entrepreneurial leadership competencies.

Drawing on the experiences and perspectives of under-graduate students and university entrepreneurship program coordinators as individuals closely associated with vari-ous types of university entrepreneurship programs, in this study we attempted to identify the roles of university en-trepreneurship development programs in developing stu-dents’ entrepreneurial leadership competencies. A review of literature on entrepreneurship education highlights the ob-jectives of entrepreneurship education programs. Then, in the section on entrepreneurship education in Malaysia we emphasize the importance of providing students with oppor-tunities to practice leadership in entrepreneurship projects and activities. The next section is allocated to competen-cies required by entrepreneurial leaders to successfully lead entrepreneurial ventures. We then present research methods and findings. Finally, we discuss implications of the findings for entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial leadership educa-tion and research.

University Entrepreneurship Education Roles in Developing Students’ Entrepreneurial

Capabilities

In less than four decades, university entrepreneurship educa-tion passed the way of evolueduca-tion from the first course offered in University of Southern California in 1971 to recently as-tonishing expansion all over the world (Heinonen & Poikki-joki, 2006; Klein & Bullock, 2006; Kuratko, 2005) as one of the most influential factors affecting students’ intentions and abilities to become entrepreneurs (Hamidi, Wennberg, & Berglund, 2008; Tan & Ng, 2006; Wilson et al., 2007; Zhao, Seibert, & Hills, 2005). The impact of entrepreneurship edu-cation is not limited to developing students’ entrepreneurial knowledge and skills but, the programs develop students’ abilities to think and act like an entrepreneur and become more effective in their personal and workplace life (Fuchs et al., 2008; Hynes & Richardson, 2007; Hytti & O’Gorman 2004; Jones, 2006; Nurmi & Paasio, 2007). However, there are not enough empirical studies on the specific roles that university entrepreneurship programs play in developing stu-dents’ entrepreneurial behavior (Anderson & Jack, 2008; Fayolle et al., 2006; Pittaway & Cope, 2007a).

Man and Yu (2007) organized the roles of entrepreneur-ship education in five groups including (a) imparting en-trepreneurial knowledge and capabilities, (b) developing

entrepreneurial skills, (c) nurturing entrepreneurial at-tributes, (d) demonstrating entrepreneurial behavior, and (e) inducing a culture of entrepreneurship among students. Souitaris et al. (2007) also classified the roles of university entrepreneurship education programs into three main types, which are learning, inspiration, and incubation. Learning means the knowledge and skills that students acquire about entrepreneurship from entrepreneurship programs. Inspira-tion is defined as “a change of hearts (emoInspira-tion) and minds (motivation) evoked by events or inputs from the program and directed towards considering becoming an entrepreneur” (Souitaris et al., p. 573). Finally, each and every component of university entrepreneurship education programs can act as incubation resources. The programs link students to groups of entrepreneurial-minded classmates and research findings and facilitate students’ access to investors, practitioners, and lecturers through networking events. Moreover, university offers funding and appropriate physical spaces for meetings. Specific to personal development of students, university entrepreneurship programs play prominent roles in students’ self-awareness of their entrepreneurial abilities through in-volving them in experiential and challenging environment for learning (Fuchs et al., 2008; Heinonen & Poikkijoki, 2006; Pittaway & Cope, 2007b). Moreover, entrepreneurship education highly enhances students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy; the strong belief in one’s abilities to successfully perform the challenging roles and tasks associated with en-trepreneurship (Barbosa, Gerhardt, & Kickul, 2007; C. Chen, Greene, & Crick, 1998; De Noble, Jung, & Ehrlich, 1999; Krueger, Reilly, & Carsrud, 2000; Shane, Locke, & Collins, 2003; Wilson et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2005). Entrepreneur-ship education also improves students’ entrepreneurial cre-ativity, the tendency and ability to create novel and useful entrepreneurial ideas and develop them to work in practice (Fuchs et al.; Hamidi et al., 2008). Entrepreneurship edu-cation has only recently recognized the importance and ne-cessity of developing students’ interpersonal and leadership competencies (Kempster & Cope, 2010; Mattare, 2008; Oku-dan & Rzasa, 2006).

Entrepreneurship Education in Malaysia

By the year 2020, Malaysia aims to become a developed country through a knowledge-based and innovative econ-omy. To achieve the vision, entrepreneurship development has been considered as vital for certain economic and social concerns that the country is struggling with, par-ticularly, increasing numbers of graduate unemployment (Abdullah, Hamali, Rahman Deen, Saban, & Abg Abdu-rahman, 2009, Jafaar & Abdul Aziz, 2008). Therefore, en-trepreneurship education turned to become compulsory in all public institutions of higher education in order to nurture positive entrepreneurial attitudes and develop entrepreneurial capabilities among university students through the creation

of a host of entrepreneurship programs and courses (Ahmad & Baharun, 2004; Jafaar & Abdul Aziz).

As a result, within the past two decades entrepreneurship education has significantly expanded throughout the coun-try (Jafaar & Abdul Aziz, 2008). Entrepreneurship related programs are offered to students in various forms includ-ing curriculum and cocurriculum activities where in curricu-lum activities students can learn theoretical aspects of new venture creation and practical aspects of entrepreneurial ac-tivities by leading university entrepreneurship projects, activ-ities, and small businesses. In a review of the entrepreneur-ship programs offered to university students in Malaysia, Cheng, Chan, and Mahmood (2009) classified the programs into two main groups including entrepreneurship courses and activities. Entrepreneurship courses include the courses and degrees offered to business administration majors and the courses and trainings offered to all of the students regard-less of their majors. Entrepreneurship activities contain co-curriculum programs including seminars, workshops, and short courses. In addition, university entrepreneurship ed-ucation programs engage students in various entrepreneur-ship and leaderentrepreneur-ship clubs such as Student in Free Enter-prise. These clubs are mostly organized by students and involve them in leading entrepreneurial activities such as social entrepreneurship programs and entrepreneurship sem-inars and workshops. The clubs also connect students to industries and entrepreneurial businesses where industrial managers and entrepreneurial leaders can share their knowl-edge and experiences with the students. In some occasions, students also have the opportunity to lead entrepreneurial projects under close supervision of entrepreneurs. Some of the universities also provide the fund and infrastructures for running a small real business and help and support students to establish a small company. However, few empirical studies examined the impact of the programs on developing students’ entrepreneurial competencies (Shariff & Saud, 2009).

Competencies of Entrepreneurial Leaders

Entrepreneurial leadership is a distinctive type of leader-ship behavior required for highly challenging and compet-itive environments (Gupta et al., 2004). Yet, the necessity and importance of interpersonal and leadership competen-cies for entrepreneurial leaders has recently been identified (Cassar, 2006; Chen, 2007; Frey, 2011; Murali et al., 2009; Surie & Ashley, 2008). To successfully overcome challenges and lead the entrepreneurial venturing to growth and devel-opment, entrepreneurial leaders must have specific compe-tencies. Swiercz and Lydon (2002) classified the competen-cies of entrepreneurial leaders into self-competencompeten-cies and functional-competencies. Self-competencies are the less tan-gible capabilities within entrepreneurial leaders, and include intellectual integrity, promoting the company rather than individual leader, utilizing external advisors, and creating

sustainable organizations. Functional competencies are the capabilities of entrepreneurial leaders related to their leader-ship task performances, and encompass operations, finance, marketing, and human resources. Although Swiercz and Ly-don specified some of the general and managerial compe-tencies of entrepreneurs, they did not illuminate the specific competencies that entrepreneurial leaders require in order to successfully lead entrepreneurial ventures. Gupta et al. (2004) concentrated on the challenges of entrepreneurial leaders in leading entrepreneurial activities in established or-ganizations. The authors highlighted entrepreneurial vision creation, commitment building, and identification of limita-tions as the most important challenges of entrepreneurial leaders. To successfully deal with these challenges, en-trepreneurial leaders must have specific personal abilities, which are proactiveness, innovativeness, and risk taking.

It is argued that entrepreneurial leaders require a com-bination of both personal and functional competencies to be able to successfully perform the critical roles and tasks of a leader in entrepreneurial ventures (Gupta et al., 2004; Vecchio, 2003). These leaders are more dependent on their personal competencies at the first stages of a new venture creation and must learn leadership skills to successfully lead their entrepreneurial ventures to growth and development (Swiercz & Lydon, 2002). Entrepreneurship scholars em-phasized the vital need of developing entrepreneurial leader-ship competencies in potential entrepreneurs and providing entrepreneurship students with leadership courses and activ-ities (Kempster & Cope, 2010; Mattare, 2008; Okudan & Rzasa, 2006).

METHOD

Qualitative Research Design

Qualitative research methods were utilized to gain a deeper understanding of the roles that university entrepreneurship education programs play in students’ entrepreneurial leader-ship learning and development. Kempster and Cope (2010) identified the urgent need for obtaining deeper knowledge about “leadership preparedness” (p. 5) that potential en-trepreneurs bring to new venture creation. Furthermore, the qualitative nature of entrepreneurial leadership learning and development phenomenon compelled entrepreneurship scholars to look beyond quantitative research methods for obtaining better knowledge about entrepreneurial leadership competencies (Kempster, 2006; Swiercz & Lydon, 2002).

Sample

The university entrepreneurship education programs under this investigation included undergraduate entrepreneurship programs in both public and private universities in Malaysia. Entrepreneurship programs vary at different universities.

These programs include both curricular and cocurricular activities. Curricular entrepreneurship programs are the courses and degrees offered to students in business ma-jors as well as students from other mama-jors. Cocurricular entrepreneurship programs are seminars, public talks, work-shops, short courses, and entrepreneurship clubs such as Stu-dent in Free Enterprise. These programs and in particular entrepreneurship clubs focus more on practical aspects of en-trepreneurship and engage students in leading entrepreneur-ship projects. To provide insights from a variety of university entrepreneurship programs in terms of the programs’ design, content, delivery methods, and activities which affect stu-dents’ entrepreneurial competencies development (Matlay, 2006), the participants were selected from both public and private universities. Convenient-purposive sampling strategy (Patton, 1990) was employed to select both research sites and participants.

All of the universities under this investigation provided entrepreneurship courses and programs both in their cur-riculum and cocurcur-riculum activities; though in different for-mats and teaching methods. Through entrepreneurship cur-riculum, students learned about theoretical foundations of entrepreneurship and practiced leadership skills by leading small groups for developing business plans or running a small simulated business as one of their assignments in en-trepreneurship courses. Enen-trepreneurship cocurriculum pro-grams in these universities involved students in entrepreneur-ship clubs and projects and running a real small business with the help and support of the university. The main focus of en-trepreneurship programs in two of the universities (one public and one private) was to develop students’ entrepreneurial competencies through providing them with the fund and physical places to launch a small company. One of the public universities linked students to entrepreneurial leaders to con-duct entrepreneurial projects under close supervision of the entrepreneurs. Moreover, all of these universities established a specific entrepreneurship centre to organize university

entrepreneurship development programs. This entrepreneur-ship center engaged students from different education back-grounds in entrepreneurship projects and activities.

Participants were drawn from both students highly in-volved in leading university entrepreneurship programs (14 students) and university entrepreneurship program coordina-tors (4 entrepreneurship program coordinacoordina-tors). The sample size indicates understanding and repetition of the contribu-tions of university entrepreneurship programs in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership competencies (Mason, 2002). The students were selected from undergraduates who at least passed a course in entrepreneurship and were suc-cessfully holding the leadership position of entrepreneur-ship clubs and activities for more than one year. This se-lection criterion ensured that the students were in a position to speak from their experiences in university entrepreneur-ship programs and entrepreneurial leaderentrepreneur-ship based on the entrepreneurial projects and activities they had led. Coordina-tors of the four universities under this investigation identified the students. Some of the students were also selected through their friends who introduced them as successful in leading entrepreneurship projects and activities. Entrepreneurship coordinators were also selected as the participants of this study based on the rational that they were involved in de-signing and implementing university entrepreneurship pro-grams and their perceptions toward students’ entrepreneur-ship competencies development critically affect the quality of the programs and consequently students’ entrepreneurship learning (Henry et al., 2005b; Johnson, Craig, & Hildebrand, 2006; Matlay, 2006).

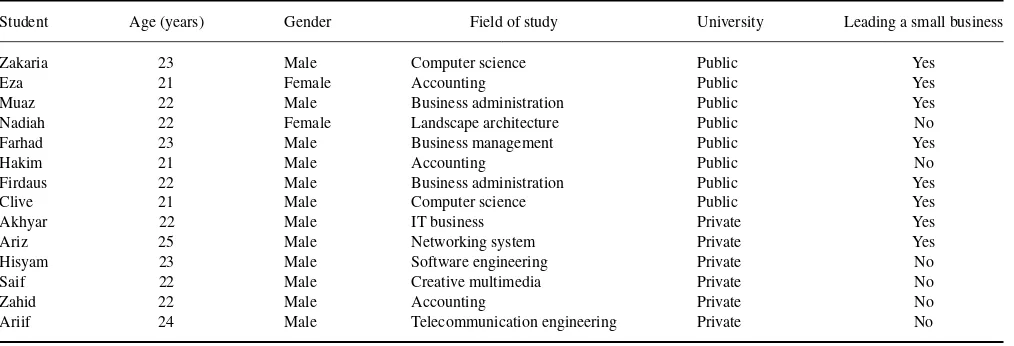

Table 1 shows the background information of the stu-dents. Of all the 14 students, eight were running small businesses in addition to leading university entrepreneurship clubs and projects. Nine of the students were holding lead-ership positions of entrepreneurial programs for more than three semesters and the other five were holding positions for two semesters. The majority of the students had different

TABLE 1

Background Information of Students

Student Age (years) Gender Field of study University Leading a small business Zakaria 23 Male Computer science Public Yes

Eza 21 Female Accounting Public Yes Muaz 22 Male Business administration Public Yes Nadiah 22 Female Landscape architecture Public No Farhad 23 Male Business management Public Yes Hakim 21 Male Accounting Public No Firdaus 22 Male Business administration Public Yes Clive 21 Male Computer science Public Yes Akhyar 22 Male IT business Private Yes Ariz 25 Male Networking system Private Yes Hisyam 23 Male Software engineering Private No Saif 22 Male Creative multimedia Private No Zahid 22 Male Accounting Private No Ariif 24 Male Telecommunication engineering Private No

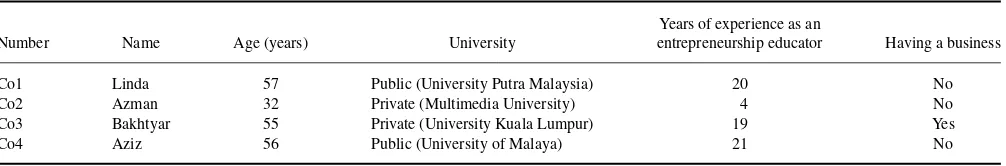

TABLE 2

Background Information of University Entrepreneurship Program Coordinators

Years of experience as an

Number Name Age (years) University entrepreneurship educator Having a business Co1 Linda 57 Public (University Putra Malaysia) 20 No Co2 Azman 32 Private (Multimedia University) 4 No Co3 Bakhtyar 55 Private (University Kuala Lumpur) 19 Yes Co4 Aziz 56 Public (University of Malaya) 21 No

education backgrounds including computer science, IT busi-ness, business administration, creative multimedia, landscape architecture, and telecommunication engineering. Eight of the students were from public universities and six students were from private universities. The average age of the stu-dents was 22 years. Two of the stustu-dents were women and the rest were men. Table 2 shows background information of university entrepreneurship program coordinators. The aver-age aver-age of the coordinators was 50 years. Three of them had almost 20 years of experience in entrepreneurship education. Three of them were male and one was female. One of the coordinators was an entrepreneur.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

Face-to-face and semistructured interviews were employed as the primary method for gaining deep insights on the roles of university entrepreneurship programs in develop-ing entrepreneurial leadership competencies of students. Semistructured interviews allowed for individual varia-tions and identification of the nonpreconceived responses and experiences of the students (Hoepfl, 1997; Souitaris et al., 2007). Moreover, semistructured interviews have been proposed as a relevant data collection technique to study entrepreneurial leadership learning and development (Kempster & Cope, 2010; Swiercz & Lydon, 2002).

A list of key interview questions for students was devel-oped based on the literature review including but not limited to, “Which of the university entrepreneurship programs did help you to learn leadership skills?”; “Which aspects of the university entrepreneurship programs did have the most ef-fect on your leadership learning and development?”; and “How did the program enhance your leadership skills?” The interview questions for coordinators were developed based on Jones’s (2006) study including “What entrepreneurial skills do you think students need?”; “How do university en-trepreneurship programs help students develop their leader-ship capabilities?”; and “Which program do you think has the most impact on students’ leadership learning?” These lists were submitted to an expert panel consisting of three local university entrepreneurship and qualitative research lecturers to ensure the content validity of the questions. The interviews lasted approximately 1 hr and were recorded on a digital au-dio recorder and transcribed verbatim within 48 hr of the actual interview.

Analysis of the dada was performed in two main phases (Grbich, 2007). First, the data were analyzed during data collection process. After each interview was conducted, we read over and over the transcribed interview and looked for the emerging issues, potential themes, gaps in data, and future research directions. This ongoing and simulta-neous data collection, coding, and analysis assisted the re-searchers in enhancing the quality of the data and revis-ing the questions for better identifyrevis-ing the roles of uni-versity entrepreneurship programs in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership competencies (Denzin, 1994). Second, the data were analyzed thematically once all of the interviews had been conducted. This phase aimed at reducing data to manageable and meaningful groups, categories, and themes based on research questions. Thematic data analysis was conducted through reading all the interview transcripts and underlining the parts where the participants described the role of university entrepreneurship programs in develop-ing their leadership competencies. Then, we read the under-lined parts of the interviews to identify the emerging issues and themes. Using constant comparative method (Merriam, 1998), the researchers analyzed the responses to the same questions and looked for similarities and differences, com-pared incidents applicable to each category, integrated the categories, and identified the themes.

Several techniques were used to ensure the trustwor-thiness of the findings of this study. We provided de-tailed transcriptions and field notes and checked the find-ings against biasness by presenting the codes, themes, and findings to some of the faculty lecturers involv-ing in entrepreneurship researches (Bogden & Biklen, 2003). Moreover, we selected those students who were successfully leading the entrepreneurship projects through coordinators and their friends to address the biases in select-ing participants and avoid selection of those students who just have the positions but were not fully involved in leading the projects and activities. Furthermore, the data collection methods were triangulated by member checking with partic-ipants where the transcribed interviews were sent to the stu-dents and coordinators for content validity confirmation and peer reviewing where the findings were presented to a group of entrepreneurship researchers in order to avoid biasness (Creswell, 2007). Finally, the researchers triangulated the data between individual interviewees, students and coordi-nators, and different entrepreneurship program coordinators.

The results of the data analysis and the emerging themes are detailed in the following sections and are discussed in the conclusion.

FINDINGS

The purpose of this study was to identify the contributions of university entrepreneurship programs in developing stu-dents’ competencies of successfully leading entrepreneurial activities. It provides the first foundations for developing theory or models for entrepreneurial leadership learning and development and new entrepreneurship development initia-tives. The findings also contribute to improve the existing entrepreneurship education programs for the sake of stu-dents’ leadership competencies development. Although not being explicitly stated in the objectives of the programs, this study identified 16 contributions of university entrepreneur-ship education programs through perspectives and experi-ences of students deeply involved in leading university en-trepreneurial projects and activities and coordinators of the programs. These 16 roles organized in two clusters including (a) student-related and (b) program-related roles. The fol-lowing sections represent each cluster with the contributions of the programs and corresponding outcomes for students’ entrepreneurial leadership learning and development.

Student-Related Roles

The first cluster of the roles of university entrepreneurship programs in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership relates to the contributions of the programs in improving stu-dents’ personal and interpersonal leadership competencies. Involvement in university entrepreneurship education pro-grams enhanced three different personal leadership qualities of the students including self-awareness, self-efficacy, lead-ership identity, and two interpersonal competencies of the students, which are communication and networking skills and managerial skills.

Personal leadership qualities. Students and coordi-nators spoke constantly about the prominent roles that uni-versity entrepreneurship education programs played in im-proving students’ self-awareness of and self-efficacy in their entrepreneurial leadership capabilities and leadership iden-tity recognition. Through providing the opportunity for stu-dents to lead entrepreneurial projects and activities, the uni-versity entrepreneurship programs made students aware of their leadership strengths, weaknesses, and needs for im-provement. For example, Zakaria emphasized that leading the entrepreneurial projects was the first time he understood that he has the capability to lead an entrepreneurial venturing: “Here...leading a real project...was the first time [that] I realized I can lead a business project. I can successfully complete the objectives.”

The programs also shaped students’ perceptions toward their competencies in leading entrepreneurial activities,

motivation to engage in leadership practices, and persever-ance in coping with the challenges and difficulties associated with entrepreneurial activities. In explaining his abilities to lead his own business, Ariif stressed the role of university en-trepreneurship activities in improving his confidence in his leadership competencies:

Before joining these activities actually...there was no

con-fidence in me. After I joined this club, I got more concon-fidence

...I know how to handle the cooperate business, I learned

how to conduct my own people, how to give tasks to the people, and how to lead them to do the tasks...and how to

handle problems.

Importantly, the programs put students in the leadership po-sition of entrepreneurial clubs and projects that highly affect in recognizing themselves as responsible for achieving the objectives of the clubs and projects and the outcomes of their group. Ariif recognized himself as the leader of the project who has the responsibility for its success:

In club, I am the organizer of the event. I took the responsibil-ity and I have to do everything by myself to make it perfect. I am the person [who] has to figure out [how to go] forward.

This leadership identity recognition had a great influence on students’ entrepreneurial leadership development through enhancing their efforts and commitment to their personal and group development.

Interpersonal leadership competencies. In addition to personal qualities, university entrepreneurship programs had a great influential impact on students’ interpersonal petencies including their confidence and maturity in com-munication skills and their ability to present their ideas and influence others. Furthermore, the programs had significant roles in enhancing students’ managerial skills including their capability in planning, delegating tasks, decision making, problem solving, and time management. When asked which skills leading the entrepreneurship activities developed in him, Firdaus stated,

I learned goal setting. Setting realistic goals so that they are achievable, so that the people don’t get de-motivated, and the works we should do to get them. I know which first thing you have to put first.

Students and coordinators constantly highlighted the con-tributions of the programs in improving students’ en-trepreneurial leadership through providing the opportunities to lead various entrepreneurial projects and activities that in-volved different groups of students with various educational backgrounds, experiences, and behaviors. This allowed stu-dents to learn leadership in relation to other stustu-dents and in different contexts.

Program-Related Roles

The second cluster of the contributions of university entrepreneurship programs in developing students’ en-trepreneurial leadership competencies is program-related roles. This cluster reflects the attributes of the univer-sity entrepreneurship programs that highly influence en-trepreneurial leadership learning and development in stu-dents. It contains leadership learning opportunities that university entrepreneurship programs provide for students, linking students to the world of entrepreneurial industries, and having a holistic approach to developing students’ en-trepreneurial competencies.

Provision of entrepreneurial leadership learning op-portunities. The participants most frequently spoke about the influential roles of university entrepreneurship programs in developing entrepreneurial leadership competencies of students through providing variety of leadership learning opportunities including experience, social interaction, ob-servation, and reflection. Through experiential learning op-portunities, university entrepreneurship programs engaged students in performing the roles and tasks of the leader in real entrepreneurship clubs, projects, activities, and small businesses. Farhad explained this point as:

Leading the club and projects actually put me in the situation that, OK...these are your tasks. There is an event that you

have to do. This is what we are going to do. Do it. That’s when you have to learn many skills...to do it. So basically

I need to call the potential sponsors and convince them and

...make sure the members are in line with the objective of

the event, doing all these I learned many leadership [skills].

These experiences had influential effects on students’ en-trepreneurial leadership learning and development through task demands and expectations and facing the challenges and problems associated with entrepreneurial activities. Practic-ing the roles and tasks of the leader in entrepreneurial activi-ties developed students’ confidence and maturity in commu-nication and interpersonal skills. University entrepreneurship programs also provided students with opportunities to inter-act with various entrepreneurial-minded people. In finter-act, the programs organized an association that brought together a rage of different people from students to educators and from entrepreneurs and sponsors to company managers and pol-icy makers where students could “chat with [their] friends and high people and ask them their opinion and network with them” (Zakaria) and learn specific entrepreneurial lead-ership behaviors and skills through sharing knowledge and experiences. Moreover, to successfully lead entrepreneurship projects and activities, the students had to interact with var-ious people inside and outside the university. These social interactions improved students’ abilities in influencing peo-ple, entrepreneurial opportunity recognition, problem solv-ing, and creativity.

Moreover, university entrepreneurship programs offered students observational learning opportunities where they learned entrepreneurial leadership competencies through di-rectly observing entrepreneurial leadership in practice. The programs provided students with the chance to directly ob-serve real life of entrepreneurial leaders as well as en-trepreneurial activities conducted by other students through arranging trips to the fields. Clive explained the influ-ential role of observing real entrepreneurs leading their ventures as:

In this club...we went to visit various fish breading sites

and then when we could see that actual thing in front of us. We saw the fish is this big. That is how I became more curious and learned how they produce the fish...and lead

the business.

These observations improved students’ entrepreneurial cre-ativity and self-efficacy. Finally, the programs had promi-nent roles in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership through providing them with reflective learning opportunities at both the collective and personal level. At collective level, the students were provided with constant and well-organized meetings where students from a project and different projects gathered together to discuss about the objectives, advantages, and disadvantages of their entrepreneurial projects and ac-tivities. In effect, the programs gave the chance to students to think, discuss, and challenge the emerging ideas in order to improve them and develop an entrepreneurial opportunity. For example, Zakaria commented:

That’s how we do as a team. We tell our opinions, every people [sic] tells and argues. This is good. This is bad. So the best idea will come. We combine to make the best idea. So we can make a good business.

At the individual level, the programs engaged students in leading entrepreneurship projects and activities. To success-fully perform the leadership tasks and roles and particularly cope with the challenges of leadership practices, the students needed to think back and analyze their previous leadership performances, problems, and failures. Hisyam explained the role of reflection on the reasons of his problems in leading the entrepreneurial projects in changing his leadership style:

[To] overcome the failure, I go back to the basic. I trace it back to the zero. For example, I had a failure in communicating the objectives with my friends....So, I thought where it

come[s] from. I thought what’s wrong with my organizing. What’s wrong with my group. So I changed the way.

This process of individual reflection highly improved the students’ leadership skills and decision making in order to avoid or prevent the problems and failures.

Linking Students to the World of Entrepreneurial Venturing

Analysis of the data revealed the significant role that uni-versity entrepreneurship programs played in connecting stu-dents to various entrepreneurial industries however, through different approaches. Only two of the four university en-trepreneurship programs developed systematic and well-organized mechanisms to link students to entrepreneurial businesses. One of the public universities under this investi-gation developed a comprehensive entrepreneurship program in which students could lead joint projects with entrepreneurs and learn entrepreneurial leadership by working with en-trepreneurial leaders in various industries. Moreover, the pro-gram involved students in different entrepreneurship projects and activities where they could practice leadership in differ-ent differ-entrepreneurial contexts. While this comprehensive pro-gram more focused on developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership through actual involvement in leadership prac-tices, one of the private universities concentrated on teaching students the process of establishing a company. This program organized students in small groups and chambers in different industries from the first day they entered the university. These groups and chambers were connected to entrepreneurs based on the businesses of their small companies. Consistent with the students, Aziz, the university entrepreneurship program coordinator, highlighted the role that his university played in linking students to the world of entrepreneurial industries:

Under this program, we send students into the industry with the lead entrepreneur that we identified and the students straight away become an entrepreneur within the system and together with the lead entrepreneur. There, they lead projects...under the guidance and supervision of the lead

entrepreneur. He has passed all the long way and he is estab-lished in the industry. So he can help students to start from small and make it bigger and bigger.

This connection between students and entrepreneurial indus-tries had an influential impact on students’ entrepreneurial leadership learning and development in many ways. First, the students could practice leadership under the guidance and support of real entrepreneurial leaders. Second, they could experience real problems and challenges inherited in leading entrepreneurial activities with less risk. Finally, they could create various networking and social interactions, which may help them in their future entrepreneurial businesses.

A Holistic Approach to Developing Students’ Entrepreneurial Competencies

Developing university entrepreneurship education programs through a holistic approach so that there existed various con-nections between entrepreneurship curriculum programs and cocurriculum activities was one of the emergent contribu-tions of the programs in developing students’ entrepreneurial

leadership competencies. This collective effort and the syn-ergy created by it helped students to more purposefully in-volve in the programs, reinforce their learning in one program by applying it in another program, and better develop their entrepreneurial capabilities. Ariz highlighted the connections between his university entrepreneurship programs and the role that this linkage plays in developing his entrepreneurial competencies:

Leading the projects...[and] the activities, we can see the

practice. In the courses they teach us the theory; how we want to make it work is in activities. So I can see what knowledge I need to use in practice. I can see the relation[ship] between them.

The universities employed different methods to connect all entrepreneurship programs, including both curricular and cocurricular activities, such as developing a comprehensive program for the programs, organizing some meetings for all the departments involved in the programs, and arrang-ing some joint programs that engaged all the departments involving in entrepreneurship education. Bakhtiar, the uni-versity entrepreneurship program coordinator who is an en-trepreneur and has 19 years of experience in enen-trepreneurship education spoke of connecting university entrepreneurship curriculum, co-curriculum, and technoperneurship (a specific department designed to develop students’ entrepreneurial creativity and innovation) through thinking together about the programs and conducting different meetings for all the departments involving in the programs:

We have our monthly meeting where we, these three groups, sit down together and exchange the information. We have seminars and the conventions where these three parties are involved. Where they meet each other and explain their prob-lems and the new ideas in entrepreneurship education.

Interestingly, the comparison between public and private uni-versities showed that employing a holistic approach to en-trepreneurship programs did not depend on being a public or private university but it highly related to the objectives and management of the programs. Two of the four universities (one public and one private) developed their entrepreneurship education programs through a holistic approach and only stu-dents of one university highlighted the purposeful linkages between the university entrepreneurship programs and the significant role that the connections play in their leadership competencies learning and development.

DISCUSSION

Despite astonishing expansion of entrepreneurship educa-tion, there is little information about the roles of the pro-grams in developing students’ entrepreneurial capabilities

(Anderson & Jack, 2008) and specifically entrepreneurial leadership competencies. From the perspectives and expe-riences of undergraduates successfully involved in leading university entrepreneurship projects and activities and en-trepreneurship program coordinators, we gained new under-standing about the contributions of university entrepreneur-ship programs in developing students’ entrepreneurial lead-ership. In a broad sense, we learned that entrepreneurship education programs play prominent roles in developing stu-dents’ entrepreneurial leadership, though the programs did not explicitly contain entrepreneurial leadership develop-ment courses and programs. This great impact necessi-tates including more purposeful entrepreneurial leadership courses and activities in university entrepreneurship educa-tion programs to develop students’ specific leadership com-petencies for entrepreneurial venturing (Mattare, 2008; Oku-dan & Rzasa, 2006).

The roles were organized in two clusters, including (a) student-related and (b) program-related roles. While previous researches mostly related the roles of university entrepreneurship programs to students (Man & Yu, 2007; Souitaris et al., 2007), here we explored the roles both in rela-tion to the students’ entrepreneurial leadership development and the design, organization, and implementation of the pro-grams. Student-related roles of the programs reflect the out-comes of involvement in the programs for students’ personal and interpersonal leadership learning and development. In terms of personal outcomes for students, the programs played prominent roles in enhancing students’ entrepreneurial lead-ership self-awareness, self-efficacy, and leadlead-ership identity recognition. This finding supports the role of entrepreneur-ship education in improving students’ entrepreneurial self-awareness and self-efficacy (Barbosa et al., 2007; Fuchs et al., 2008; Heinonen & Poikkijoki, 2006; Wilson et al., 2007) and highlights the contribution of the programs in students’ entrepreneurial leadership identity recognition that highly affects their leadership learning and development. This ne-cessitates providing students with the opportunities to lead entrepreneurial projects and activities through which they can improve their leadership identity and competence.

Program-related roles are the contributions of the pro-grams in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership including provision of various learning opportunities (ex-periential, social interactive, observational, and reflective learning opportunities), linking students to the world of en-trepreneurial venturing, and having a holistic approach to uni-versity entrepreneurship education programs. Accordingly, students learn and develop their entrepreneurial leadership in the process of practicing real leadership roles and tasks in entrepreneurial projects and activities, interacting with various entrepreneurial-minded people with diverse knowl-edge and experiences, observing real entrepreneurial lead-ership in practice, and reflecting on their leadlead-ership perfor-mances at both collective and individual levels. There may exist some elements of entrepreneurial leadership learning in

present university entrepreneurship programs (Fuchs et al., 2008; Pittaway & Cope, 2007a), however the findings of this study indicate that a combination of all these learning op-portunities highly affects entrepreneurial leadership learning and development in students. Moreover, the programs played their prominent roles in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership through connecting students to the world of en-trepreneurial venturing and having a holistic approach to university entrepreneurship programs, the importance of which have been emphasized by previous research findings (Hannon, 2006; Pittaway & Cope).

Implications for Entrepreneurship Education

Through identifying the roles that university entrepreneur-ship programs play in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership, this study provides contributions to the present entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial leadership education literature. It expands the literature on the impacts of the programs on students’ entrepreneurial capabilities devel-opment (Man & Yu, 2007; Souitaris et al., 2007) and we have related the contributions of the programs to both students and the organization of the programs. It also has many implica-tions for entrepreneurship education. The entrepreneurship education roles emerging from this study can provide a foun-dation to develop new entrepreneurship education programs and include entrepreneurial leadership courses and activities in the programs. Entrepreneurship educators can also use the findings for improving existing entrepreneurship education programs in order to develop the specific competencies re-quire for leading entrepreneurial ventures in students. It can also provide basis for innovative ideas to the way that en-trepreneurial leadership education is delivered. Each contri-bution of the programs offers opportunities to generate new ideas for entrepreneurial leadership program features and take actions to develop students’ entrepreneurial leadership competencies.

REFERENCES

Abdullah, F., Hamali, J., Rahman Deen, A., Saban, G., & Abg Abdurahman, A. Z. (2009). Developing a framework of success of Bumi-puteraentrepreneurs.Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy,13, 8–24.

Ahmad, F. S., & Baharun, R. (2004).Interest in entrepreneurship: An ex-ploratory study on engineering and technical students in entrepreneur-ship education and choosing entrepreneurentrepreneur-ship as a career. Johor Bahru, Malaysia: Faculty of Management and Human Resource Development, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

Anderson, A. R., & Jack, S. L. (2008). Role typology for enterprising educa-tion: The professional artisan?Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development,15, 256–273.

Barbosa, S. D., Gerhardt, M. W., & Kickul, J. R. (2007). The role of cog-nitive style and risk preference on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and en-trepreneurial intentions.Journal of Leadership and Organizational Stud-ies,13, 86–104.

Baron, R. A. (2007). Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: How entrepreneurs “connect the dots” to identify new opportunities.Academy of Management Perspectives,20, 104–119.

Bogden, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2003).Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods(4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Busenitz, L. W., West, G. P. III, Shepherd, D., Nelson, T., Chandler, G. N., & Zacharakis, A. (2003). Entrepreneurship research in emergence: Past trends and future directions.Journal of Management,29, 285–308. Cassar, G. (2006). Entrepreneur opportunity and intended venture growth.

Journal of Business Venturing,21, 610–632.

Chen, C., Greene, P., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers?Journal of Business Venturing,

13, 295–316.

Chen, M. H. (2007). Entrepreneurial leadership and new ventures: Creativity in entrepreneurial teams. Creativity and Innovation Management,16, 239–249.

Cheng, M. Y., Chan, W. S., & Mahmood, A. (2009). The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in Malaysia.Education+Training,51, 555–566.

Creswell, J. W. (2007).Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches(2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

De Noble, A., Jung, D., & Ehrlich, S. (1999). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. In R. D. Reynolds, W. D. Bygrave, S. Manigart, C. M. Mason, G. D. Meyer, H. J. Sapienza, and K. G. Shaver (Eds.),Frontiers of en-trepreneurship research(pp. 73–78). Waltham, MA: P&R Publications Inc.

De Pillis, E., & Reardon, K. K. (2007). The influence of personality traits and persuasive messages on entrepreneurial intention: A cross-cultural comparison.Career Development International,12, 382–396. Denzin, N. (1994). The arts and politics of interpretation. In N. Denzin &

Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.),Handbook of qualitative research(pp. 500–515). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fayolle, A., Gailly, B., & Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: a new methodology.Journal of European Industrial Training,30, 701–720.

Frey, R. S. (2011).Leader self-efficacy and resource allocation decisions: A study of small business contractors in the federal marketspace. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest, UMI Dissertation Publishing.

Fuchs, K., Werner, A., & Wallau, F. (2008). Entrepreneurship educa-tion in Germany and Sweden: what role do different school systems play?Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development,15, 365– 381.

Grbich, C. (2007).Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gupta, V., MacMillan, I. C., & Surie, G. (2004). Entrepreneurial leadership: developing and measuring a cross-cultural construct.Journal of Business Venturing,19, 241–260.

Hamidi, D. Y., Wennberg, K., & Berglund, H. (2008). Creativity in en-trepreneurship education.Journal of Small Business and Enterprise De-velopment,15, 304–320.

Hannon, P. D. (2006). Teaching pigeons to dance: Sense and meaning in entrepreneurship education.Education+Training,48, 296–308. Heinonen, J. (2007). An entrepreneurial-directed approach to teaching

cor-porate entrepreneurship at university level.Education+Training,49, 310–324.

Heinonen, J., & Poikkijoki, S.-A. (2006). An entrepreneurial-directed ap-proach to entrepreneurship education: mission impossible?Journal of Management Development,25, 80–94.

Henry, C., Hill, F., & Leitch, C. (2005a). Entrepreneurship education and training: can entrepreneurship be taught? Education +Training,47, 158–169.

Henry, C., Hill, F., & Leitch, C. (2005b). Entrepreneurship education and training: can entrepreneurship be taught? Education +Training,47, 98–111.

Hoepfl, M. C. (1997). Choosing qualitative research: A primer for technol-ogy education researchers.Journal of Technology Education,19, 47–63. Holmgren, C., From, J., Olofsson, A., Karlsson, H., Snyder, K., & Sundtr¨om, U. (2005). Entrepreneurship education: Salvation or damnation?Journal of Entrepreneurship Education,8, 7–19.

Hynes, B., & Richardson, I. (2007). Entrepreneurship education: A mech-anism for engaging and exchanging with the small business sector. Edu-cation+Training,49, 732–744.

Hytti, U., & O’Gorman, C. (2004). What is “enterprise education”? An analysis of the objectives and methods of enterprise education programs in four European countries.Education+Training,46, 11–23.

Jafaar, M., & Abdul Aziz, A. R. (2008). Entrepreneurship education in developing country, Exploration on its necessity in the construction pro-gramme.Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology,6, 178–189. Johnson, D., Craig, J. B. L., & Hildebrand, R. (2006). Entrepreneurship

education: towards a discipline-based framework.Journal of Management Development,25, 40–54.

Jones, C. (2006). Enterprise education: revisiting Whitehead to satisfy Gibbs.Education+Training,48, 336–347.

Kempster, S. J. (2006). Leadership learning through lived experience: A process of apprenticeship?Journal of Management and Organization,

12, 4–22.

Kempster, S. J., & Cope, J. (2010). Learning to lead in the entrepreneurial context.Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research,16, 5–34. Klein, P. G., & Bullock, J. B. (2006). Can entrepreneurship be taught?

Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics,38, 429–439. Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of

entrepreneurial intentions.Journal of Business Venturing,15, 411–432. Kuratko, D. F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education:

devel-opment, trends, and challenges.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,

29, 577–597.

Kuratko, D. F. (2007). Entrepreneurial leadership in the 21st century.Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies,13(4), 1–11.

Man, T. W. Y., & Yu, C. W. M. (2007). Social interaction and adolescent’s learning in enterprise education: An empirical study.Education+ Train-ing,49, 620–633.

Mason, J. (2002).Qualitative researching. London, England: Sage. Matlay, H. (2005). Researching entrepreneurship and education part 1:

What is entrepreneurship and does it matter?Education+Training,47, 665–677.

Matlay, H. (2006). Researching entrepreneurship and education Part 2: What is entrepreneurship education and does it matter?Education+Training,

48, 704–718.

Mattare, M. (2008, January).Teaching entrepreneurship: The case for an entrepreneurial leadership course. Paper presented at USASBE, San An-tonio, TX.

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

Merriam, S. B. (1998).Qualitative research and case Study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mitra, J., & Matlay, H. (2004). Entrepreneurial and vocational education and training: lessons from eastern and central Europe.Industry and Higher Education,18, 53–69.

Murali, S., Mohani, A., & Yuzliani, Y. (2009). Impact of personal quali-ties and management skills of entrepreneurs on venture performance in Malaysia: Opportunity recognition skills as a mediating factor. Techno-vation,29, 798–805.

Nurmi, P., & Paasio, K. (2007). Entrepreneurship in Finnish universities.

Education+Training,49, 56–66.

Okudan, G. E. and Rzasa, S. E. (2006). A project-based approach to en-trepreneurial leadership education.Technovation,26, 195–210. Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods

(2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Peterman, N. E., & Kennedy, J. (2003). Enterprise Education: influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,28, 129–145.

Pittaway, L., & Cope, J. (2007a). Entrepreneurship education: A system-atic review of the evidence.International Small Business Journal,25, 479–510.

Pittaway, L., & Cope, J. (2007b). Simulating entrepreneurial learning: In-tegrating experiential and collaborative approaches to learning. Manage-ment Learning,38, 211–233.

Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation.

Human Resource Management Review,13, 257–279.

Shariff, M. N. M., & Saud, M. B. (2009). An attitude approach to the prediction of entrepreneurship on students at institution of higher learn-ing in Malaysia.International Journal of Business and Management,4, 129–135.

Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources.Journal of Business Venturing,22, 566–591.

Stewart, W. H., Watson, W. E., Carland, J. C., & Carland, J. W. (1998). A proclivity for entrepreneurship: a comparison of entrepreneurs, small business owners, and corporate managers.Journal of Business Venturing,

14, 189–214.

Surie, G., & Ashley, A. (2008). Integrating pragmatism and ethics in en-trepreneurial leadership for sustainable value creation.Journal of Busi-ness Ethics,81, 235–246.

Swiercz, P. M., & Lydon, S. R. (2002). Entrepreneurial leadership in high-tech firms: a field study.Leadership and Organization Development Jour-nal,23, 380–386.

Tan, S. S., & Ng, C. K. F. (2006). A problem-based learning approach to entrepreneurship education.Education+Training,48, 416–428. Vecchio, R. P. (2003). Entrepreneurship and leadership: common trends and

common threads.Human Resource Management Review,13, 303–327. Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial

self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for en-trepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31, 387–401.

Wu, S., & Wu, L. (2008). The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in China.Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development,15, 752–774.

Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions.Journal of Applied Psychology,90, 1265–1272.