Obesity, Attractiveness, and

Differential Treatment in Hiring

A Field Experiment

Dan-Olof Rooth

a b s t r a c t

This study presents evidence of differential treatment in the hiring of obese individuals in the Swedish labor market. Fictitious applications were sent to real job openings. The applications were sent in pairs, where one facial photo of an otherwise identical applicant was manipulated to show the individual as obese. Applications sent with the weight-manipulated photo had a significantly lower callback response for an interview: Six percentage points lower for men and eight percentage points lower for women. This differential treatment occurs differently for men and women: The results for men are driven by attractiveness, while the results for women are driven by obesity.

I. Introductions

A large body of literature has analyzed the correlation between body weight and labor market outcomes.1Cawley (2004) presents three explanations as to why such a correlation could exist. First, low wages or employment rates could cause obe-sity, for instance as a result of poorer people consuming cheaper, more fattening foods. Second, unobserved variables—such as lack of self-confidence—could cause both obe-sity and low wages or employment rates. Third, obeobe-sity might lower wages or employ-ment rates, for instance by lowering productivity or because of employer discrimination.2

Dan-Olof Rooth is a professor of economics at Kalmar University in Sweden. He would like to thank an anonymous referee, Martin Nordin, Inga Persson, Kirk Scott, participants at the EALE conference in Oslo and the ESPE conference in Chicago and participants at seminars at Tinbergen institute and Kalmar, Lund and Stockholm university (SOFI) for comments and helpful suggestions. Magnus Carlsson and Klara Johansson provided excellent research assistance. A research grant from Kalmar University is gratefully acknowledged. The data used in this article can be obtained beginning January 2009 through 2012 from Dan-Olof Rooth, Kalmar university, email: Dan-Olof.Rooth@hik.se [Submitted May 2007; accepted March 2008]

ISSN 022-166X E-ISSN 1548-8004Ó2009 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

T H E J O U R NA L O F H U M A N R E S O U R C E S d 4 4 d 3 1. See Section II.

This study focuses exclusively on the latter link, asking whether obese job appli-cants are treated differently in the hiring process after controlling for differences in observed qualifications, that is, keeping the supply side constant. To this end, it uses a field experimental approach that identifies differences in labor market outcomes caused exclusively by weight manipulation of facial photographs attached to job applications. Although the initial focus of the study is obesity, the weight manipula-tion turns the job applicant not only into an obese individual, but also lowers his/her attractiveness. We therefore try to disentangle whether employers act exclusively on the obesity signal or whether (less) attractiveness also plays a role in the hiring de-cision, and how this differs between men and women.3

Interviews conducted in Sweden show that nine out of ten managers believe that em-ployment decisions do depend upon the applicant’s obesity. A major reason for this be-lief is that obese applicants are expected to be less productive (Dagens Nyheter 2003).4 This highlights the possible role of statistical discrimination in hiring decisions. Other studies also document that obesity is correlated with bad health (see Burtonet al.1998; Pronk, Tan, and O’Connor 1999) and higher absenteeism (Leigh 1991; Parkes 1987), which further increases the probability that statistical discrimination against obese appli-cants is prevalent in the hiring process. Also, Agerstro¨m, Carlsson, and Rooth (2007) find that a large majority of Swedish managers strongly associate negative productivity with being obese, relative to being of normal weight. Based on these facts, one would expect that obese job applicants would be treated differently in the Swedish labor market. This differential treatment depends on the underlying mechanisms, that is, employer or customer preferences, and/or productivity differences based on weight/ attractiveness, and on whether the expected obesity/unattractiveness penalty is a com-mon one or varies across occupations.

Since 1979, psychologists and sociologists have been documenting systematic dif-ferential treatment by employers against obese applicants in laboratory settings (see Roehling 1999 for an excellent overview of these studies). However, there have been no previous attempts to isolate the effect of employers’ perceptions of obese/unat-tractive job applicants on real life labor market outcomes. Most studies use survey data on wages, weight, and/or attractiveness. Identifying the effect of employer per-ceptions on outcomes is difficult using such nonexperimental register/survey data be-cause not all differences in productive characteristics can be accounted for.

Making inferences about differential treatment against obese/unattractive persons from interview data is also problematic for a number of reasons. Upon questioning, employers don’t necessarily express their true attitudes toward these applicants; and, even if they do, their attitudes are not automatically consistent with their behavior. Hence, due to the shortcomings of traditional register/survey and interview data and the inconsistency between attitudes and behavior, complementary studies using field experimental methods are required.

To circumvent this difficulty, researchers have relied on using field experiments designed specifically to test for ethnic and gender discrimination in recruitment

3. Many studies analyze whether the obesity penalty also varies across other demographic groups. See for instance Cawley (2004) for differences across ethnic groups. We focus solely on majority male and female Swedes.

4. See Korn (1997) for similar results for American managers.

(see Riach and Rich 2002). To our knowledge, this empirical strategy has not been implemented before to measure the degree of differential treatment toward obese job applicants.5Correspondence testing in this particular situation implies that the re-searcher sends two equal applications to advertised job openings with the only dif-ference being the photo attached to the application: one obese and the other of normal weight. This methodology ensures that productive characteristics on the sup-ply side are held constant.6The degree of differential treatment is quantified by the difference between the two groups in the number of callbacks for a job interview. In this context, the Swedish labor market is an ideal market to analyze because the use of photographs in job applications is quite common; hence, it is not only employed by attractive job applicants (see Section III and footnote 15 for a discussion on this).7 Using the correspondence-testing method, our experimental field data was col-lected between January and August 2006 by sending applications to job openings in seven different occupations in the Stockholm and Gothenburg labor market areas. In total, we replied to 989 job openings. We find that the callback rate to interview was six and eight percentage points lower for obese male and female applicants, re-spectively, than for nonobese applicants. Interestingly, an attractiveness grading of the applicants’ facial photos shows that obese men and women are perceived as less attractive. When including the attractiveness rating into the regressions, the results for women seem to be driven by obesity, while the results for men seem to be driven by being less attractive.

The Swedish National Institute of Public Health (2006) reported that 44 percent of Swedish males and 28 percent of females aged 18–84 can be classified as overweight, and another 11 percent of both groups can be classified as obese.8Hence, a large share of the population is potentially being treated differentially in the hiring situation.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section II presents a selec-tion of previous studies within this area, while Secselec-tion III shows how obesity was signalled through the use of facial photographs. Section IV presents the design of the experiments as regards the choice of occupations and the construction of appli-cations, while Section V presents the descriptive results. In Section VI, an effort is made to explain the obesity difference in callbacks and how this is affected by the inclusion of attractiveness into the models, while Section VII paints a picture of the share of obese individuals in certain occupations, addressing whether variation in differential treatment across occupations has led to occupational sorting. Section VIII concludes.

5. Weichselbaumer (2003) also used pictures in the correspondence-testing framework to study sexual ori-entation discrimination in hiring.

6. Hence, while some recent studies use variation in application information to analyze how treatment varies across application attributes (see Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004), we use the same application attributes for both applicants. Our strategy was chosen to focus on whether, and if so how, firm and recruiter characteristics were correlated with the obesity difference in callback rates.

7. Interviews with recruiters at some large Swedish companies show that quite a few applications have a personal photo attached to them. They estimate that is the case for every fifth application they receive. 8. Body Mass Index (BMI) is calculated as the person’s weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of his/ her height (in meters). A male is classified as overweight if his BMI is between 25 and 30 and classified as obese if his BMI is over 30. The corresponding numbers for women are 23.8, 28.6, and over 28.6, respec-tively.

II. Previous Studies— Obesity, Attractiveness, and

Labor Market Outcomes

In laboratory settings, psychologists and sociologists have docu-mented differential treatment by employers toward the obese (see Roehling 1999). In such experiments, subjects are asked to make hiring decisions about hypothetical employees where the only difference is the subject’s weight. The results of these studies show that differential treatment on the basis of a person’s weight can be found in a number of employment decisions (including compensation, placement, and promotion). These studies often have found that differential treatment due to weight is more common for women than for men. However, the extent to which these experimental results have external validity is questionable.

Most of the early work on the correlation between obesity and (real) labor market out-comes involves U.S. data. Register and Williams (1990), Averett and Korenman (1996), and Cawley (2004) all use the same data, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youths (NLSY), to estimate an obesity effect.9Averett and Korenman use a variety of method-ological approaches to address the possibility that reverse causality (that is, poor employ-ment outcomes may cause obesity), and/or that an unobserved factor causes both obesity and poor employment outcomes. For example, using multiple reports of body weight and sibling differences, they attempt to cancel out the effects of shared family environment and genetics. Cawley takes the analysis one step further by instrumenting mother’s weight with child’s weight and ends up with obesity wage penalties quite similar to those in Averett and Korenman. Overall, these studies find a sizable and statistically significant obesity wage penalty for women, while the results for males are more mixed.

Using other U.S. data sets, Hamermesh and Biddle (1994) and Behrman and Rose-nzweig (2001) find no effect of weight on wages. In their study, Behrman and RoseRose-nzweig use data on identical twins from the Minnesota Twins Registry in order to address specifi-cally the issue of endowment heterogeneity.

There are also a growing number of studies using European data. For instance, the studies by d’Hombres and Brunello (2005), Garcia and Quintana-Domeque (2006), and Lundborget al.(2006) document the correlation between obesity and labor mar-ket outcomes for a number of European countries. The results confirm the picture that emerges from the U.S. studies, that there is no consensus overall ‘‘effect’’ be-tween obesity and labor market outcomes for men and women. The study by Garcia and Quintana-Domeque (2006), for nine European countries using the European Community Household Panel (ECHP), finds a negative correlation between wages and obesity, ranging from -2 to -10 percent for women; for men, no country estimate is lower than -2 percent, and five estimates are in fact positive.

Interestingly, the strongest negative correlation is found for women in the Scandina-vian countries of Finland and Denmark.10This gender pattern also is confirmed in the studies by Greve (2007) for Denmark and by Sarlio-Lahteenkorva and Lahelma (1999) for Finland. Lundborget al.(2006), using data from the Survey of Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), also find that obesity is negatively associated with

9. See also the study by Pagan and Davlia (1997). 10. Sweden is not part of that data set.

wages for women but not for men. However, although negative, many of the correla-tions for women are not statistically significant. Hence, it is an open question as to whether, or to what extent, the obese are differentially treated in the labor market based on employer perceptions (preferences and/or expectations about productivity).

As mentioned in the introduction, the weight manipulation of our facial photo-graphs lowers applicants’ attractiveness, so that those perceived as attractive are now perceived as unattractive. Hence, the literature on economic outcomes and attractiveness is related to the obesity literature. In an experimental setting Mobius and Rosenblat (2006) find that attractive persons receive higher wages because they are perceived as more able, conditional on productive skills. The study by Hamermesh and Biddle (1994) estimates an unattractiveness penalty of about 5–10 percent on wages after controlling for weight in their model specifications. Harper (2000) estimates a similar model for the United Kingdom, finding an unattractiveness penalty of 11 and 15 percent for women and men, respectively, but an obesity penalty only for women. Also, both studies find only a small variation in the unattractiveness penalty across occupations, indicating that general employer discrimination is the main explanation for their findings.11However, the bulk of the literature on attrac-tiveness does not control for weight/obesity. While gender differences findings are quite robust in the obesity literature, the meta-analyses of Langlois et al. (2000) and Hosoda, Stone-Romero, and Coats (2003) find no gender differences in the beauty premium for labor-related outcomes.

From this literature review, the overall picture is that men and women are evalu-ated positively, and similarly, on attractiveness while women alone seem to be eval-uated negatively when obese. Hence, an empirical analysis requires the examination of men and women separately.

III. Signalling Obesity Through Photos

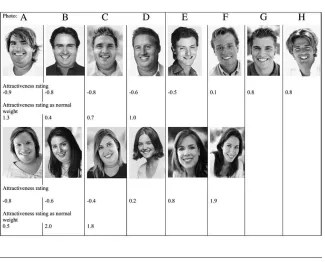

We signal obesity by attaching a portrait photograph to the job appli-cation. In this section, we describe the procedure by which the photos were chosen. First, approximately 100 photos of young men and women (approximately 20–30 years old) that were of normal weight but varied attractiveness were collected from an Internet photo site (www.photosearch.com). From this pool of photos, approxi-mately 50 were chosen by a group of five evaluators (three male and two female researchers). The criteria was to choose sets of at least five photos of individuals with similar looks where each set varied according to attractiveness, from being perceived as unattractive to very attractive, and neglecting the far end category of very unat-tractive applicants. A total of 25 male and 23 female photos were selected. These photos then were distributed randomly and eventually graded on attractiveness (on a nine-point scale) and age by 150 students at Kalmar University.12 In order to

11. Both studies, however, also find some support for occupation-specific discrimination or for productivity effects. For instance, Harper finds large pay penalties for unattractive women in clerical jobs and for obese women in craft occupations.

12. In practice, five students evaluated the 48 photos in the same order, then another five students in another order, and so forth. Hence, 30 different orders of the photos were used.

control for differences in average grading across students, the deviance of an individ-ual student’s average grading of the photos was calculated for each of the 48 photos. We (the evaluators) then used this information, together with ‘‘eye-balling’’ to choose photo pairs that were valued approximately the same on attractiveness. Our aim was to choose pairs as identical as possible with regards to such features as clothing, hair color, hair length, smile, and facial shape (see Table A1 in Appendix 1). The image of the (somewhat) more attractive individual of the two then was sent to a photo firm, www.mikeelliottfineart.com, for manipulation into appearing obese. The background of the photos also was changed to be the same within pairs. This strategy thus minimizes the probability that photo characteristics other than appear-ance through the weight manipulation are driving the result.13

Finally, seven pairs of photos (four male and three female) were used in the study (see Table A1 in Appendix 1). The obvious drawback of using only a few photos is that the results could be specific to just these photo pairs and not generalized to a greater population.14 The experimental design acknowledges this to some extent by using photo pairs that vary according to attractiveness. Nonetheless, we use only a small number of photo pairs.

At this stage, it is still unclear to what extent the manipulated photos signal only obesity or trigger attitudes or stereotypes toward obese applicants. To some extent, this has been studied already using two alternative methods. First, a total of 87 stu-dents at Kalmar University were asked to report the first three attributes that came to mind when viewing the photo of the obese applicant, as presented in the job appli-cation being sent to the employers. In order to be realistic in a job appliappli-cation setting, only the photographs of individuals who smiled and looked happy were used in the experiment (see Table A1 in Appendix 1).15Not surprisingly, almost everyone (94 percent) reported positive attributes such as pleasant, happy, and outgoing, while half of them (53 percent) also reported that the person looks fat, large, or plump. How-ever, a large majority of the persons not reporting a ‘‘fat’’ attribute were women, and quite a few of them revealed afterward that they did not want to report that the person was fat. In the second analysis, we evaluated to what extent the weight manipulation also changed the attractiveness of the face being manipulated into obesity (see Sec-tion IIIA below). This is the (un)attractiveness rating used in the empirical analysis.

13. One could be worried that employers observe that the photos have been manipulated. However, when distributing the manipulated photos to 87 students for evaluation (see below), none replied that the photos looked odd or manipulated.

14. At first glance there are alternative strategies available. One could, for instance, also use photos of obese individuals and manipulate those into being normal weight. However, it is very problematic to ma-nipulate photographs of the obese since their bone structure is often not visible. Another strategy would have been to use a large sample of photos that varied according to weight and attractiveness. However, since the personal attribute one would like to measure needs to be strongly signaled when sending job applica-tions, our choice was to focus on a clear obesity signal instead of a continuum of weights. Hence, we be-lieved the treatment strategy, turning one of two equally attractive individuals into obese, to be a more successful and transparent one.

15. It is very unlikely that a job applicant would send a personal photo where he/she did not look happy. This also was confirmed in employer interviews: although varying according to attractiveness, the appli-cants’ photos attached to job applications most of the time showed a smiling face. The reader should be aware that we are using a sample of photos that include individuals perceived as unattractive (but smiling), but notveryunattractive.

A. Obesity and Unattractiveness

After the weight manipulation, we again evaluated all of the photos on attractiveness. In this setting, the manipulated photo was included as both obese and normal weight. For men we then had 12 photos, of which eight were used in the final field experi-ment, and another 24 pictures of males of varying attractiveness and weight but sim-ilar age. For women we then had nine photos, of which six were used in the field experiment, and another 31 pictures of females of varying attractiveness and weight but similar age. We then distributed these photos randomly and they were eventually graded on attractiveness by students at Kalmar University. A total of 88 students, 55 percent female, with an average age of 24, participated. We asked the participants to grade according to what they generally perceive as average attractiveness for that age; they had five levels to choose from:very unattractive,unattractive,average, at-tractive andvery attractive. Assuming linearity in attractiveness, these categories were given the values -2, -1, 0, 1, and 2, respectively. In order to control for differ-ences in average grading across students, the deviance in an individual student’s av-erage grading of the photos was calculated for each of the 36 and 40 male and female photos, respectively. The average grading across all photos was -0.5 for the female photos and -0.2 for the male photos.

Table A1 in Appendix 1 shows a variation in attractiveness for both the male and female sample of photos, but especially so for the women. Also, the weight manip-ulation changed the attractiveness rating of the manipulated photos from being per-ceived, on average, as attractive (having a value close to one) to being perceived as unattractive (having a value close to minus one). It is therefore possible that differ-ential treatment of obese and normal weight applicants by employers is driven by obesity and/or by attractiveness. An attempt will be made to disentangle the two effects in the empirical analysis.

Also, for both men and women, the variation in attractiveness across the photos diminished considerably once they had been manipulated. While the difference in the attractiveness rating were 0.9 and 1.5 for men and women, respectively, between the highest and lowest graded photo not yet manipulated this difference decreased to 0.3 and 0.4 when the photos were manipulated into being obese.

IV. Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted between January and August 2006. During this period, all employment advertisements in selected occupations found on the web page of the Swedish employment agency were collected.16A clear ma-jority of employers posting vacant jobs at this site want to have applications sent in by e-mail only. This facilitates our experimental design of attaching photos, because it can be done electronically. In total 1,970 applications were sent to 985 employers. Callbacks for interviews were received via telephone (voice mailbox) and e-mail. To minimize inconvenience to the employer, invitations were promptly declined.

16. According to labor related laws, all new vacancies should be reported to the Swedish employment agency. However, these laws are not enforced and therefore all vacancies are not reported. Still, it is the one site where most vacant jobs are to be found.

A. Choice of Occupations

To make satisfactory progress in the collection of cases, it was necessary for the de-mand for labor to be relatively high in the chosen occupations. In addition, the skill requirement and the degree of customer contact needed to vary across occupations. Hence, the selected occupations were both skilled and semi/unskilled, and included relatively high as well as low contact with customers. In the end, the experiment was restricted to seven occupations and two major cities in Sweden: Stockholm and Gothenburg. The selected occupations were computer professionals, business sales assistants, preschool teachers, accountants, nurses, restaurant workers (mostly waiters), and shop sales assistants.

B. Construction of Applications

The applications had to be realistic while not referring to any real persons. Also, be-cause the competition from other applicants was considerable, the testers had to be well qualified, that is, to have skills comparable to above average applicants for that job. A number of real life (written) applications available on the webpage of the Swedish employment agency were used as templates and adjusted and calibrated for our purposes (see Appendix 2 and 3 for a detailed description).

Applicants had identical human capital within occupations and were of similar age (varying between 25 and 30 across occupations); had similar amounts of work experi-ence in the same occupation as the job applied for (varying between two and four years across occupations); and had obtained their education in the same type of school, but at different locations. The application consisted of a quite general biography on the first page and a detailed CV of education and work experience on the second page.

The application also contained a name, an email address, a telephone number, and a postal address. The e-mail address and the telephone number (including an auto-matic answering service) were registered at a large Internet provider and a phone company for each fictitious applicant. Postal addresses were included in the resumes to prevent any invitations being lost or returned to the employer. The addresses were chosen to signal that the respondents lived in the same neighborhood.

For each occupational category, four applications designed to be perceived as nearly identical but without creating employer suspicion were constructed for men and women (that is, combinations of two names and two application types). See Appendix 2 for a detailed description. These applications were randomly attached to the photo pairs. Be-cause of practical limitations, we ended up with systematic differences in the names and applications used for normal weight versus obese facial photographs within occupa-tions. However, we argue in Appendix 2 that name and application type effects are very unlikely to be affecting our results because only the most common Swedish names are used, and applications more or less vary only according to technical design, that is, the fonts and font size used and the order in which the information is presented.

We always sent the obese application first and the normal weight application two, or at most three, days later. Hence, our results could be affected by a ‘‘sent first’’ ef-fect, but other similar studies that we have done on ethnicity and gender, sending half of the population before the other and vice versa, indicate that no such effects exist. See Carlsson and Rooth (2007, 2008). This may be explained by the applications be-ing sent very close in time.

V. Descriptive Results

Table 1 shows the aggregated results of the experiment for men and women separately. The first column tells us that the two applications were sent for a total of 985 different job openings, 527 for the men and 458 for the women. Because correspondence testing focuses only on the first step of the hiring process—being called for an interview—and thus neglects the second step of actually getting the job, there are four possible interview outcomes: neither invited, both invited, or only the normal weight or obese individual being invited for an interview. In 317/249 cases, neither male/female applicant was invited. In the remaining 210/209 cases, at least one of the applicants was invited to interview. Both applicants were invited in 130/118 cases, while only the normal weight applicant was invited in 56/63 cases, and only the obese applicant in 24/28 cases. From this information, we can calculate separately the callback rate of normal weight and obese applicants, respectively, as well as the relative callback rate and the difference in callback rates for men and women. Only the results for the latter measure are discussed.17

The design of the experiment ensures that the difference in callbacks between the manipulated and nonmanipulated photos is attributable to firms/recruiters using in-formation extracted from the photo as a decision variable in the process of selecting whom to call for an interview. The callback rate is found to be significantly lower for weight manipulated (obese/unattractive) applicants. On average, it is six and eight percentage points lower than for nonmanipulated (normal weight/attractive) male and female applicants, respectively.18

Table 1 also gives the same type of data description for each of the seven job cat-egories separately. The results for women diverge somewhat from those for men in that there is more variation across occupations. For both men and women, we find three within-occupation obesity differences in callback rates to be statistically signif-icant. For men, the obesity difference is of a similar magnitude, varying between seven and 11 percentage points for all three occupations—business sales assistants,

restaurant workers,andshop sales assistants—all occupations with a great deal of customer contact. For women, there is more variation in the magnitude of the obesity difference in callback rates: Twenty-one percentage points forrestaurant workers, 15 percentage points foraccountantsand seven percentage points forpreschool teach-ers. However, we do not find a statistically significant obesity difference in callback rates for either men or women in the occupations computer specialistsor nurses. Hence, with the exception of these two occupations, the occupational obesity differ-ence in callback rates is not the same for men and women.

Because men and women apply to different jobs, some jobs may have fewer male than female applicants. With a smaller number of applicants, the results may not be statistically significant. Thus, when we only focus on statistically significant esti-mates, we may get an incorrect picture. For instance, the obesity difference in

17. Since there are differences in the average callback rate across occupations, the interpretation of the results could vary depending on whether we focus on relative callback rates or absolute differences in call-back rates. In this study, the two measures yield a similar picture of the variation across occupations. 18. In the empirical analysis, that is, the regressions, the obesity difference in callback rates using all obser-vations was not found to be statistically different between the Stockholm and Gothenburg labor market areas.

Table 1

Aggregated results for the correspondence testing. Men and women separately

Callback rates

Table 1 (continued)

Callback rates

Jobs

Neither Invited

At least one invited

Equal Treatment

Only normal weighted

invited

Only obese invited

Normal

Weighted Obese

Relative callback rate (8/7)

Difference in callbacks

(8-7) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10)

Preschool teachers 109 42 67 46 15 6 0.56 0.48 0.85 20.07** Accountants 50 34 16 7 8 1 0.30 0.16 0.53 20.15** Nurses 45 20 25 19 2 4 0.47 0.51 1.10 0.04 Restaurant workers 71 42 29 11 17 1 0.39 0.17 0.43 20.21*** Shop sales assistants 33 30 3 2 1 0 0.09 0.06 0.67 20.08 Women total 458 249 209 118 63 28 0.40 0.32 0.81 20.08***

Notes: The null hypothesis for the statistic in Column 10 is Column 7¼ Column 8. It is calculated using thesigntestcommand in Stata 9.0. *, **, and *** denote the 10, 5, and 1 percent significance level, respectively.

720

The

Journal

of

Human

callback rates is in the same ‘‘ballpark’’ for both sexes inbusiness sales,shop sales, andpreschool teachers, and to some extent also foraccountants, even if the differ-ence is larger for women.

Some of the differences in differential treatment across occupations also might be due to occupational variation in labor supply. Column 7 of Table 1 shows that the occupationsnursesandaccountantshave the highest callback rate; this indicates that they might have fewer applicants to select from, but it also could be due to recruiting practices including calling more applicants for interviews.19

To conclude, it is unclear what picture of the obesity difference in callbacks we would get by using a larger sample. Still, there is more variation in the results for women across occupations, which indicates the possible existence of differences in the underlying mechanisms as regards the results for men and women. This topic is analyzed in the next section.

VI. Empirical Analysis

In this section, we analyze the effect of the weight manipulation on the probability of being called for interview using probit regressions (that is, reporting mar-ginal effects from the dprobit command in Stata and clustering standard errors on the job level). All models include occupation fixed effects when applicable.20Also, we compare the results of using only the indicator for being manipulated into being obese (Model 1) to using only the attractiveness rating (Model 2), and to including them both simultaneously (Model 3). We are potentially able to identify Model 3 because there is variation in attractiveness within the obese and normal weight sample.

However, because there is a high correlation (above 0.7 for both samples) between the two variables, it may be empirically difficult to identify separately the coeffi-cients, especially if the samples are small. Therefore, we constructed an aggregated occupational grouping for sales occupations: business sales assistants, shop sales assistants, andrestaurant workers. For the other occupations, there are no obvious grouping criteria and they are presented separately. The data for analysis thus include 1,054 and 916 male and female observations, respectively. They are found in Table 1.

A. Obesity Differences in the Probability of Being Invited for an Interview

The analysis begins by regressing the callback dummy on both the obesity indicator variable (Being obese) and occupation fixed effects (when applicable), first for the full sample and then separately for each occupation.21The first column of Table 2

19. The correlation between Column 7 and 9 in Table 1 is -0.7 and -0.1 for men and women, respectively. 20. The results in this section are unaltered whether we use the linear probability model or themargfx com-mand in Stata. Also, since both applications are sent to the same employers, the results differ only margin-ally when we exclude occupation fixed effects.

21. An earlier version analyzed whether workplace and recruiter characteristics were associated with the obesity difference in the probability of being invited for an interview. None of the included variables—the sex of the recruiting person, the share of male employees at the firm, the number of employees at the work-place and whether the firm is a public sector employer—were found to be statistically different from zero. See Rooth (2007) for these results.

Table 2

Disentangling the effect of obesity and unattractiveness on the probability of callback for interview. Marginal effects (percentage points). Men and women

Men Women

Variable Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Number of

cases Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Number of cases

All occupations

Being obese 20.07*** — 0.03 1,054 20.08*** — 20.08* 916 [0.02] [0.05] [0.02] [0.05]

Unattractiveness rating — 20.04*** 20.06** — — 20.03*** 0.00 — [0.01] [0.03] [0.01] [0.03]

By occupation

Sales

Being obese 20.09*** — 0.01 568 20.11*** — 20.03 434 [0.02] [0.05] [0.03] [0.07]

Unattractiveness rating — 20.05*** 20.06** — — 20.06*** 20.05 — [0.01] [0.03] [0.02] [0.04]

Computer professionals

Being obese 20.08 — 20.01 72 0.08 — 0.17 74 [0.07] [0.09] [0.07] [0.04]

Unattractiveness rating — 20.04 20.07 — 0.02 20.06 — [0.04] [0.16] [0.05] [0.09]

722

The

Journal

of

Human

Nurses

Being obese 0.01 — 0.00 158 0.04 — 20.03 90 [0.05] [0.08] [0.05] [0.16]

Unattractiveness rating — 0.01 0.02 — 0.04 0.05 — [0.02] [0.15] [0.05] [0.11]

Accountants

Being obese 20.02 — 20.01 106 20.14** — 20.08 100 [0.04] [0.06] [0.06] [0.11]

Unattractiveness rating — 20.01 20.01 — — 20.07** 20.04 — [0.02] [0.11] [0.04] [0.07]

Preschool teachers

Being obese 20.07 — 20.15** 150 20.08** — 20.30*** 218 [0.05] [0.08] [0.04] [0.11]

Unattractiveness rating — 20.06** 0.21 — — 0.00 0.12** — [0.02] [0.15] [0.02] [0.05]

Notes: This table reports marginal effects for the probability of being invited for an interview based on probit regressions. Columns 1 and 5 report the marginal effect of being obese after controlling for occupation fixed effects using the model Prob(Callback¼1)¼a+b*Obese+c*Occfor men and women, respectively. Model 2, Columns 2 and 6, uses the same model but switches the variableBeing obesewith the standardizedUnattractiveness rating, while Model 3 includes both variables and uses the model Prob(Callback¼1)¼a+b*Obese+c*Unattractiveness+d*Occ. (See Columns 3 and 7.) The first two rows use all observations, while Rows 3 through 12 use observations only within occupational categories.Salesoccupations includebusiness sales,shop sales,andrestaurant work. *, **, and *** denote the 10, 5 and 1 percent significance level, respectively. Reported standard errors (in brackets) are adjusted for clustering on the job.

Rooth

reveals that applications with a facial photograph of an obese male applicant have a seven percentage point lower probability of being called for an interview than appli-cations with photos of normal weight males. The corresponding number for women is eight percentage points (fifth column). As a next step, we allow for separate effects of obesity on the callback rate for each occupation. The obesity difference is similar in magnitude; it varies between seven and nine percentage points for men insales

occupations, computer professionals, and preschool teachers, but only the results forsalesoccupations are statistically significant. As would be expected from the pre-vious section, we find no obesity difference in callback rates for men in the occupa-tionsaccountantsandnurses. For women, we find a similar but somewhat ‘‘stronger’’ result: the obesity difference in callback rates is larger, -11 and -14 percentage points, for sales occupations and accountants, respectively. Also, for preschool teachers

there is an obesity penalty of eight percentage points. These differences are statisti-cally significant for all three occupations. We find no obesity difference in callback rates forcomputer professionalsandnurses. Hence, the results to this point suggest a somewhat more general obesity penalty for women than for men. Now we turn to (un)attractiveness as an alternative explanation of the results.

B. Attractiveness Differences in the Probability of Being Invited for an Interview

The analysis begins by regressing the callback dummy on the standardized unat-tractiveness rating variable (Unattractiveness rating) and occupation fixed effects (when applicable) for the full sample and then separately for the five occupa-tions.22The data show that one standard deviation in this variable is approximately equivalent to the difference between being unattractive (-1) and being average at-tractive (0).

We find that a single standard deviation difference in unattractiveness lowers the probability of being called for an interview by four percentage points for men and by three percentage points for women (see the second and sixth column of Table 2). As a next step, we allow for separate effects of attractiveness on the callback rate for each occupation. For men, the unattractiveness penalty is of the same mag-nitude, four to six percentage points, for sales occupations,preschool teachers, andcomputer professionals, but only the first two estimates are statistically signif-icant. As in the previous section, we find no unattractiveness difference in callback rates foraccountantsandnurses. For women, we find that the unattractiveness dif-ference in callback rates is statistically significant for sales occupations and

accountants, where a job applicant who is one standard deviation more unattrac-tive than another has a six and seven percentage point lower probability of receiv-ing a callback for an interview, respectively. For the other occupations, we find no unattractiveness difference in callback rates. Contrary to the previous section on obesity, these results suggest a more general unattractiveness penalty that is sim-ilar for men and women.

We also investigate how differences in attractiveness are associated with the probability of being invited for an interview within the obese and normal weight samples separately. This analysis is identical to the one above and regresses the

22. The unattractiveness rating is simply the attractiveness rating in Section III multiplied by -1.

callback dummy on the standardized unattractiveness-rating variable ( Unattrac-tiveness rating) and on occupation fixed effects for each of the four samples. There is much less variation in attractiveness among the obese photos, both for men and women, than among the normal weight ones. (See Table A1 in Appendix 1.)

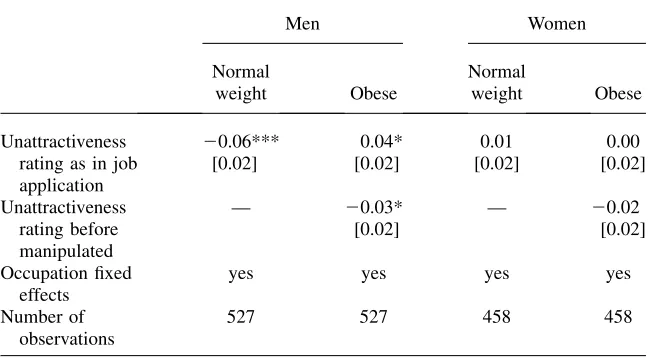

In this analysis, we find the unattractiveness rating to be an important determi-nant for the probability of receiving a callback for an interview for the men but not for the women (see Table 3). The estimate for normal weight men is very similar to the one in Table 2 for the full sample. Somewhat surprisingly, the estimate for obese men is positive, and statistically significant. This can probably be explained by a combination of small variation in attractiveness and photo-specific effects. Interestingly, when using instead the attractiveness rating as normal-weight before-being-manipulated-into-obese, which has more variation, we get a statisti-cally significant estimate with the expected negative sign. This suggests that stu-dents graded all obese applicants very similarly on attraction, while employers see beyond obesity whenÔevaluatingÕon attraction. This exercise indicates that attrac-tiveness is an important decision variable in the hiring situation for men, while that is not the case for women.

To conclude so far, the results on obesity are somewhat stronger for women than for men, while the opposite holds for attractiveness. Hence, the underlying mecha-nisms for why men and women are treated differently based on looks could differ. In the next section, we will attempt to disentangle the two effects by including both in the regression at the same time.

C. Being Obese or Being Unattractive

To investigate whether it is obesity or attractiveness or both that drives the results, we return to Table 2 and Model 3. We now add both the obesity dummy and the unat-tractiveness rating into the model, as well as the occupation fixed effects. Specifi-cally, we regress the callback dummy on the obesity indicator variable, the (un)attractiveness rating, and the occupation fixed effects. That is, we estimate the model Prob(Callback¼1) ¼a + b*Obesity + c*Unattractiveness + d*Occupation

fixed effects.23Column 3 shows that for men, a one standard deviation increase in the unattractiveness rating lowers the probability of a callback for interview by six percentage points, while being obese does not alter this same probability. The same regression for women yields the opposite result: Being obese lowers the probability of a callback for interview by eight percentage points, while being more unattractive does not alter this same probability.

This result—that attractiveness, but not obesity, is important for the hiring prob-ability of men—holds forsalesoccupations, where we find a strong and statisti-cally negative impact of being unattractive. For women in the same occupations, we do not find a differential treatment for being obese or being un-attractive. As already mentioned, it can be problematic to estimate Model 3 by

23. We have also worked with nonlinear effects in unattraction, without finding any, as well as with an in-teraction effect between obesity and unattraction, asking whether unattractive obese job applicants receive an additional penalty in callbacks. It was not possible for us to estimate this reliably and we got extremely large coefficients and even larger standard errors.

occupation, which is especially apparent for both the male and female sample of

preschool teachers. These results are unreliable, with too large coefficients, and are not commented upon further. For the other occupations—accountants,nurses, andcomputer professionals—we do not find obesity, or unattractiveness, to be an important determinant of the probability of receiving a callback for interview.

The basic picture from the previous sections is more or less unaltered. We find that looks are equally important for men and women in the hiring situation, but the chan-nels through which this occurs differ: attraction is somewhat more important for men, while obesity is somewhat more important for women. However, the high cor-relation between the two variables casts doubt on whether we have truly separated the two effects or whether this is just a spurious finding.

D. Why Do Employers Act on Looks in the Hiring Situation?

The fact that the relative callback rate varies across occupations suggests the pres-ence of statistical discrimination, that is, that employers act on expectations about productivity differences across the two groups (see Hamermesh and Biddle 1994). However, because the difference in callbacks depending on looks is higher in occupations requiring customer contact—that is, sales occupations—this indicates

Table 3

The probability of callback for an interview. Marginal effects (percentage points). Men and women

Notes: This table reports marginal effects of the standardizedUnattractivenessrating on the probability of being invited for an interview for the normal weight and obese samples separately using probit regressions. *, **, and *** denote the 10, 5 and 1 percent significance level, respectively. Reported standard errors (in brackets) are adjusted for clustering on job. The standard deviation in the unattractiveness rating in the sam-ple of normal weight male, obese male, normal weight women and obese women is 1.5, 0.5, 2.0, and 0.5, respectively.

that preference-based customer discrimination may be a possible explanation for the results (Becker 1957).24Further, the variation in the appearance penalty across occupations suggests that employer preferences, as in Becker (1957), are not the ex-planation.

VII. Occupational Sorting of the Obese in the Swedish

Labor Market

The occupation-specific obesity difference in treatment that is found implies that there should be occupational sorting away from certain occupations. Us-ing aggregate Swedish data, we examine whether occupational sortUs-ing exists for the obese. To our knowledge, the Survey of Living Conditions (or ULF, see Statistics Sweden) is the only representative Swedish database that includes information about height and weight as well as occupation. Unfortunately, we did not find a data set that included attractiveness as a variable.

Aggregate information from ULF (see Table 4) shows that both employed and nonemployed men are somewhat more frequently overweight than women in the same states are, but that the sexes are similarly frequently obese. From this data (not in the table), it is also evident that obese women have a 12 percentage point lower probability of being employed than normal weight women. However, for obese men this difference is only four percentage points, but is statistically signif-icant. Hence, this result resembles the empirical findings for wages/earnings in Section II, in that labor market differences related to obesity are stronger for women.

One particular occupation stands out for the employed.Restaurant workers—men, and to a lesser extent women—have by far the highest share of obese employees, while there is little variation in the share of obese employees in the other occupa-tions.Restaurant workis also the occupation with the highest degree of differential treatment by weight. Hence, obese individuals are more concentrated in an occupa-tion where differential treatment toward them is high just the opposite of what occu-pational sorting theories would predict. The explanation for this result must be that individuals sort themselves into this occupation prior to becoming overweight/obese, and/or that the supply of obese applicants is large enough to (over)compensate for the differential treatment effect.

Finally, this result also highlights the problem with regular register data in trying to uncover only the behavior of employers.

VIII. Conclusion

This study is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to examine by means of correspondence testing the extent of differential treatment in the hiring

24. We attempted to distinguish between jobs that required more customer contact by reading and extract-ing information from the job ads. However, they were not very detailed on this point.

Table 4

Share of overweight/obese individuals within categories, men and women 31-55 years old, 2001-2005

Men Women

Overweight +

obese Obese

Difference in callbacks

Overweight+

obese Obese

Difference in callbacks

Not employed 58 16 — 46 18 —

Employed as: 56 11 — 34 8 —

Computer professionals 45 6 20.08 25 2 0.09 Business sales assistants 54 8 20.11 24 6 20.06

Accountants 47 7 20.05 24 6 20.07

Preschool teachers 60 0 20.06 26 6 20.15

Nurses 33 0 0.01 33 5 0.04

Restaurant workers 66 33 20.10 47 18 20.21 Shop sales assistants 59 11 20.07 33 7 20.08

Source: Aggregate information from the Survey of Living Conditions (ULF), Statistics Sweden. There are very few observations of men in the occupationspreschool teachersandnursesand none found to be obese. Being ‘‘overweight’’ is defined as having a BMI score above 25 but less than 30, while being ‘‘obese’’ is defined as having a BMI score above 30.

728

The

Journal

of

Human

process among applicants with unfavorable looks (that is, the obese or unattrac-tive). Our aggregate results show that job applicants with average looks (normal weight/attractive) are at least 20 percent more likely to receive a callback for an interview than job applicants with unfavorable looks (obese/unattractive). This difference is exclusively attributed to the weight manipulation of the photos that are attached to the job application. How important this difference in callbacks is for differences in finding jobs is difficult to predict. However, the results imply that applicants with average looks (normal weight/average attractive) get called to in-terview approximately four times for every ten jobs they apply for, while appli-cants with unfavorable looks (obese/unattractive) need to apply to 12 jobs to achieve the same number of callbacks. Unless jobs are scarce, this effect is not likely to be strong.25

It is also possible to compare these results to the level of differential treatment against other groups in the labor market. Using an identical research strategy and the same occupations, from Carlsson and Rooth (2007), it is found that male job applicants with a native Swedish sounding name have a 40 percent higher proba-bility of receiving a callback for an interview than job applicants with a Middle Eastern sounding name. Hence, the differential treatment against the obese is lower, but in the same ‘‘ballpark’’ as that against the Middle Eastern minority in Sweden. A similar conclusion also obtains when comparing our result to the dif-ferential treatment in hiring found against African-Americans, women, and older workers in the United States and using a similar methodology.26

When investigating whether the results on looks are driven by obesity per se or by variations in attractiveness and whether this differs between men and women, we find that the results tend to be driven by obesity for women, but tend to be driven by at-tractiveness for men. To some extent, this is in accordance with previous results in the literature.

In an earlier version of this article, we did not find any patterns to explain the dif-ference in callbacks when we included recruiter characteristics and/or firm/work-place characteristics. The only significant variation in treatment between normal weight and obese job applicants was between occupations. The obese job applicant was called less often to interview in occupations that included personal contacts with customers, such as sales and restaurant jobs. Still, we are reluctant to draw any con-clusions as to whether it is statistical discrimination, customer discrimination, or a combination of both that is driving the results.

25. However, the estimated obesity difference in callbacks is probably a lower bound. A photo of the ap-plicant is used to signal that he/she is obese. It is not certain that the employer has observed this signal but it will be when the person shows up for the interview.

26. Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) find that applicants with white sounding names are 50 percent more likely to receive a callback for an interview than applicants with African-American sounding names, while Lahey (2008) finds that younger applicants are (at least) 40 percent more likely to receive a callback for an interview than older workers. Neumark, Bank, and Van Nort (1996) find evidence of sex discrimination that varies between high- and low-price restaurants. Men are more likely to receive a callback for an interview in high-priced, and women in low-priced, restaurants. In both instances, the preferred sex is more than twice as likely to receive a callback for an interview.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Description of Application Construction and Sending

An ideal design for this experiment would be to send photos of two job applicants, presented as a normal-weight applicant in the first case and the same person manip-ulated into looking obese in the second case. These photos then would be attached to an identical job application and sent to job openings. Using this design, any differ-ential treatment by employers would be due solely to the weight manipulation of the photo. However, for obvious reasons such a strategy is not possible to implement empirically without employers being suspicious. Hence, we had to use a design as

Table A1

Attractiveness ratings of the photos sent to employers.

Note: The four male and three female faces to the left have been manipulated into being obese. The attractiveness ratings come from a sample of 89 students whose average age is 24 and of whom 45 percent are female. We eval-uated a total of 40 female and 36 male photos. Attractiveness ratings ranged fromvery unattractive to very attrac-tive, on a five-point scale from -2 to +2, with average attractiveness of 0. For each participant and each photo, we calculated the difference between the ratings of the photo and his/her average rating. The average of these differ-ences across participants yields the photo-specific attractiveness ratings found in the table. The photo pairs for men are A-H, B-E, C-G and D-F, while the photo pairs for women are A-D, B-F and C-E.

similar as possible to this without creating suspicion; that is, to use similar but dif-ferent names, application texts, and photos.

The first two objectives were met by using the same names and application types as in Carlsson and Rooth (2007, 2008), while the third objective was discussed at length in Section III. In their studies, Carlsson and Rooth found no systematic differ-ences in callback rates between the two male/female names or between the different occupation specific applications being used. Hence, if one assumes that this finding could be generalized to hold for all employers, then we would not need to randomize names and applications to photos. Still, we did.27

Construction of Job Applications

Job seekers can upload their CV on the webpage of the Swedish employment agency for employers to view. From this source, Carlsson and Rooth (2007) collected ap-proximately 20 templates for each occupation, which were finally rewritten into only two application types per occupation (see appendix C for the ones used incomputer specialistoccupation, having been translated into English). The constructed applica-tion types consist of a quite general biography on the first page and a detailed CV (not shown) of education and work experience on the second page. The only differ-ences between the two types of applications are the font and font size (Verdana 10 or Times New Roman 12), the placement of the attached photo (not in the study by Carlsson and Rooth, eight male/six female), and the names used (two male/female). The content in the two applications is the same and is formulated in a similar, but not identical, way. Colleagues at Kalmar University were asked to assess whether the applications were perceived as similar in qualifications within occupations, and applications were rewritten if not.

Collection of Jobs and Sending Applications

Having constructed the application types, the next step was to collect jobs from the webpage of the Swedish employment agency and to design a method for combining names, applications, and photos. A clear majority of employers wanted to have the job applications sent by e-mail only. Hence, all applications were sent by email, which facilitated our experimental design, allowing us to attach photos to applica-tions electronically. All correspondence from the employers came by e-mail or phone (to a voice mailbox). We got no replies by regular mail in this experiment.

In order to speed up the process of sending applications, we had to send bundles of ten jobs with the same application composition, instead of randomly creating each ap-plication. Sending bundles of applications using the same names and application types instead of single applications probably made the process about ten times faster.28

27. We had the choice of using many different names and applications for each occupation, with no prior information on how they were perceived, or to choose the ones that were found to be perceived as identical in the related studies by Carlsson and Rooth. We decided upon the latter.

28. For each name we have an Internet provider, for instance Hotmail, which implies that if we had not used bundles, then for each job we would have had to draw a name, entailing logging out from the previous name and logging in using the new name. Also, for every job the random application drawn would have to be found and attached. Such a strategy would most likely imply more mistakes in sending the wrong ap-plication combination; for instance, one name in the hotmail and another one in the attached apap-plication.

Within the 40 jobs applied to, we used all possible combinations of names and ap-plication types attached to the obese and normal weight applicants, respectively.29

One potential drawback with sending bundles of the same applications is that even if we combine photos, names, and application types randomly, if we do not send all possible combinations we create systematic differences in the share of specific names and applications across the obese and normal weight applications. For instance, hav-ing three photo pairs and four application combinations, we would need to apply for 120 jobs to include all name/application type/photo pair combinations. At most we applied to 113 jobs for women in business sales, but for as few as 33 for women in shop sales. However, this systematic pattern is only a problem for interpretation of the results if there are name and application type effects, which we argue is unlikely. Even if we cannot guarantee that name and application effects do not exist, we have a lot of variation in names and application types between obese and normal weight applicants. It seems very unlikely that such similar names and applications would create the system-atic difference we observe between obese and normal weight applicant callback rates.

By using photos, we give up some element of control, because we do not know what information employers act on in the photos. But great effort has been made to make the photos as similar to each other as possible within pairs in terms of pic-ture background, hair color, hair length, clothing etc. Again, such a strategy is only empirically possible using a small number of photos; what we gain in control, we lose in generalizability. Hopefully, the only variation across applications after this lengthy experimental design is the one in obesity and in attractiveness. The extent to which there still exists an interaction effect, between the application text and photo attributes, is not known and unfortunately is impossible to evaluate.

Appendix 3

Application exemplars translated into English:

Computer specialists

Application A

Hi,

My name is Karl Johansson and I am 30 years old. Previously I worked as a system designer at Telenor AB between 1998 and 2005 in an environment based on win2000/SQL Server. I then participated in three different projects and my work contained development, maintenance and every day problem solving. Development

work was done in ASP, C++and Visual Basic

and we used the development platform .Net and

29. For instance, if the obese application was given the name Erik Nilsson and application A, then the nor-mal weight had to have the name Karl Johansson and application B. Constructing such pairs prevented us from sending the same name or application twice to the same employer.

MS SQL. In addition I have experience in HTML, XML, J2EE and JavaScript.

I enjoy working with development and problem solving. And I now hope that I will develop further at your company. To my personal characteristics one could add that I find it easy to work both on my own and in a group. I am a dynamic person who likes challenges. I really like my occupation which I think is mirrored in the work I do. I have a degree in computer engineering. I graduated with good grades from Stockholm university.

In my spare time I like to read and listen to music. Me and my wife also like to socialize with our friends during weekends.

I look forward to being invited for interview and I will then bring my good certificates and diplomas.

Best regards Karl Johansson

Application B

Hi,

First of all I would like to introduce myself. My name is Erik Nilsson, and I am 29 years old and live in Stockholm.

I previously worked at EssNet AB for about 7 years and my work tasks included designing, implementing as well as testing different financial applications. The pro-gramming was mainly done in a Java J2EE environment. A lot of the development was also done in C/C++and Visual Basic. Sometimes I also participated in projects which were more web based and linked to data bases. This work gave me experience in ASP, JSP and MS SQL among other things.

To my skills one could also add a great work joy and that I do not want to finish up work only half done. I work independently and am good at taking own initiatives. At my previous job I also learned how to cooperate and to listen to others and together create great results.

As regards my educational background I have an engineering degree in technical physics with a focus on computer science at Uppsala University.

Since I am a very social person a great deal of my spare time is spent together with my friends and my wife. Traveling is also a great interest of mine. I hope I will get

the opportunity to come for an interview and then get the chance to tell you more about myself and to show my good grades and credentials.

Best regards Erik

References

Agerstro¨m, Jens, Rickard Carlsson, and Dan-Olof Rooth. 2007. ‘‘Ethnicity and Obesity— Evidence of Implicit Work Performance Stereotypes in Sweden.’’ IFAU WP 2007:20. Uppsala, IFAU.

Averett, Susan, and Sanders Korenman. 1996. ‘‘The Economic Reality ofthe Beauty Myth.’’

Journal of Human Resources31(2):304–30.

Becker, Gary. 1957.The Economics of Discrimination.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Behrman, Jere R., and Mark R. Rosenzweig. 2001. ‘‘The Returns to Increasing Body

Weight.’’ University of Pennsylvania WP 01–052. Philadelphia.

Bertrand, Marianne, and Sendhil Mullainathan. 2004. ‘‘Are Emily and Greg More Employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Discrimination.’’

American Economic Review94(4):991–1014.

Burton, Wayne N., Chin-Yu Chen, Alyssa B. Schultz, and Dee W. Edington. 1998. ‘‘The Economic Costs Associated with Body Mass Index in a Workplace.’’Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine40(9):786–92.

Carlsson, Magnus, and Dan-Olof Rooth. 2007. ‘‘Evidence of Ethnic Discrimination in the Swedish Labor Market Using Experimental Data.’’Labour Economics14(4):716–29. Carlsson, Magnus, and Dan-Olof Rooth. 2008. ‘‘An Experimental Study of Sex Segregation in

the Swedish Labor Market: Is Discrimination the Explanation?’’ IZA DP #3811, Bonn, IZA.

Cawley, John. 2004. ‘‘The Impact of Obesity on Wages.’’Journal of Human Resources

39(2):451–74.

Dagens Nyheter. 2003. ‘‘Fo¨retag nobbar o¨verviktiga.’’Dagens Nyheter, February 27, p. 11. D’Hombres, Beatrice, and Giorgio Brunello. 2005. ‘‘Does Obesity Hurt Your Wages More in

Dublin than in Madrid? Evidence from the ECHP.’’ IZA DP #1704. Bonn, IZA. Garcia, Jaume, and Climent Quintana-Domeque. 2006. ‘‘Obesity, Employment, and Wages in

Greve, Jane. 2007. ‘‘Obesity and Labor Market Outcomes: New Danish Evidence.’’ Aarhus School of Business WP 13/07. Aarhus.

Hamermesh, Daniel S., and Jeff E. Biddle. 1994. ‘‘Beauty and the Labor Market.’’American Economic Review84(5):1174–94.

Harper, Barry. 2000. ‘‘Beauty, Stature, and the Labour Market: A British Cohort Study.’’

Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics62(1):771–800.

Hosoda, Megumi, Eugene F. Stone-Romero, and Gwen Coats. 2003. ‘‘The Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Job-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies.’’

Personnel Psychology56(2):431–62.

Korn, Jane B. 1997. ‘‘Fat.’’Boston University Law Review77(1):25–67.

Langlois, Judith H., Lisa Kalakanis, Adam J. Rubenstein, Andrea Larson, Monica Hallam, and Monica Smoot. 2000. ‘‘Maxims or Myths of Beauty? A Meta-Analytical and Theoretical Review.’’Psychological Bulletin126(3):390–423.

Lahey, Joanna N. 2008. ‘‘Age, Women, and Hiring: An Experimental Study.’’Journal of Human Resources43(1):30–56.

Leigh, Paul J. 1991. ‘‘Employee Attributes as Predictors of Absenteeism in a National Sample of Workers: The Importance of Health and Dangerous Working Conditions.’’Social Science and Medicine33(2):127–37.

Lundborg, Petter, Kristian Bolin, So¨ren Ho¨jgrd, and Bjo¨rn Lindgren. 2006. ‘‘Obesity and Occupational Attainment among the 50+ of Europe.’’ InAdvances in Health Economics and Health Services Research,Vol. 17: The Economics of Obesity, ed. Bolin, Kristian, and John Cawley. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Mobius, Markus M., and Tanya S. Rosenblat. 2006. ‘‘Why Beauty Matters.’’American Economic Review96(1):222–35.

Neumark, David, Roy J. Bank, and Kyle D. Van Nort. 1996. ‘‘Sex Discrimination in Restaurant Hiring: An Audit Study.’’Quarterly Journal of Economics111(3):915–41. Pagan, Jose A., and Alberto Davlia. 1997. ‘‘Obesity, Occupational Attainment, and

Earnings.’’Social Science Quarterly8(3):756–70.

Parkes, Kathy R. 1987. ‘‘Relative Weight, Smoking, and Mental Health as Predictors of Sickness and Absence from Work.’’Journal of Applied Psychology72(2):275–86. Pronk, Nicolaas P., Agnes W. H. Tan, and Patrick J. O’Connor. 1999. ‘‘Obesity, Fitness, and

the Willingness to Communicate and Health Care Costs.’’Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise33(11):1535–43.

Register, Charles A., and Donald R. Williams. 1990. ‘‘Wage Effects of Obesity Among Young Workers.’’Social Science Quarterly71(1):130–41.

Riach, Peter A., and Judith Rich. 2002. ‘‘Field Experiments of Discrimination in the Market Place.’’Economic Journal112(483):F480–F518.

Roehling, Mark V. 1999. ‘‘Weight-Based Discrimination in Employment: Psychological and Legal Aspects.’’Personnel Psychology52(4):969–1016.

Rooth, Dan-Olof. 2007. ‘‘Evidence of Unequal Treatment in Hiring Against Obese Applicants: A Field Experiment.’’ IZA DP #2775, Bonn, IZA.

Sarlio-Lahteenkorva, Sirpa, and Eero Lahelma. 1999. ‘‘The Association of Body Mass Index with Social and Economic Disadvantage in Women and Men.’’International Journal of Epidemiology28(3):445–49.

Statistics Sweden. 2003.Swedish Occupational Register.Stockholm, Statistics Sweden. Swedish National Institute of Public Health. 2006. Their web page at www.fhi.se. Weichselbaumer, Doris. 2003. ‘‘Sexual Orientation Discrimination in Hiring.’’Labour

Economics10(6):629–42.