Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:15

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Using Web-Based Foreign Advertisements in

International Marketing Classes

Jason Ryan

To cite this article: Jason Ryan (2011) Using Web-Based Foreign Advertisements in International Marketing Classes, Journal of Education for Business, 86:3, 171-177, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.493902

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.493902

Published online: 24 Feb 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 103

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.493902

Using Web-Based Foreign Advertisements in

International Marketing Classes

Jason Ryan

University of Redlands, Redlands, California, USA

The author examines the use of the Web-based foreign advertisements for enhancing the inter-national awareness of undergraduate marketing students. An analysis compares the adaptation of advertisements for identical products to the cultural perceptions and values of consumers in different countries. In a sample of 110 international marketing students, 41% rated the analysis of foreign advertisements as “useful” and 41% “highly useful”; 71% of students observed highly significant differences between foreign and domestic advertisements, 29% perceived moderate differences.

Keywords: foreign advertisements, internet, marketing, teaching

In this article I suggest a simple and effective method for sensitizing students to cultural differences by using the In-ternet to show them foreign advertisements and then engage them in an exploration of why approaches to advertising that differ sharply from those used in the United States ap-peal to selected foreign audiences. This relates to a wider challenge in American education: enabling students to over-come the limits of their own circumstances and situations and gain insights into the global world. This is especially critical for marketing and business students who, whether they stay home or go abroad, will be competing in a global economy. Clearly, there are no quick fixes or magical so-lutions to opening minds to other cultures and societies. What is required—as has always been the case—is seri-ous study of many subjects (e.g., history, culture, foreign languages, psychology, sociology, economic systems) and in-depth encounters with the peoples and institutions of other cultures. Universities have long dealt with this chal-lenge through a variety of means, including lectures, ex-hibits and cultural events; foreign study programs; bringing foreign students and professors to campus; and, in general, trying to open the university to the world beyond it. Many institutions proclaim the measures they have taken to make their marketing curricula international, but research suggests that such efforts reach only a relatively small percentage of

Correspondence should be addressed to Jason Ryan, University of Redlands, Department of Business Administration, 1200 East Colton Avenue, Duke Hall 306, Redlands, CA 92374, USA. E-mail: jason [email protected]

students and have little impact even on many of those who are reached (Tyagi, 2001). Studies have shown, for instance, that American students have alarmingly low levels of knowledge of geography (Hise, 1991; Hise, Davidow, & Tray, 2000; Hise, Shin, Davidow, Fahy, Solano-Mendez, & Troy, 2004). Cunningham and Jones (1997) have, moreover, demon-strated that geographical knowledge has not been empha-sized or encouraged in most international marketing courses. Broader cultural knowledge is even more lacking and pro-viding that is a considerably more serious and challenging undertaking.

It is thus not surprising that the lament that many students remain isolated from the powerful currents of globalization that are transforming the world they live in is often heard (Thanopoulos & Vernon, 1987). The students themselves seem equally frustrated at the inadequacy of standardized curricula and textbooks to prepare them for international employment, especially careers in international marketing (Turley and Shannon, 1999). The approach to this problem advocated here is not to add new courses on different aspects of globalization, but to find ways to enrich the content of ex-isting courses with materials, exercises, and approaches that may cause students to observe and reflect on cultural differ-ences and values. Indeed, a proliferation of new courses in-tended to broaden the knowledge and experiences of students might have a detrimental impact by drawing their attention away from core courses and basic concepts and skills. In most programs, the need is not to try to do more by packing additional materials into already overstuffed curricula, but to find ways of doing better by using class time more effectively to develop an awareness of cultural differences and values

172 J. RYAN

and how they impact perceptions, including those relevant to consumer behavior.

In this article I first present a brief review of the literature examining the teaching of intercultural proficiency in busi-ness schools and then specific Web sites that feature a large selection of foreign advertisements. I then provide practical suggestions concerning the use of specific types of adver-tisements and the manner in which they can be effectively presented and discussed. As an illustration, three examples of advertisements are presented and discussed from an inter-cultural perspective. Finally, I provide statistical data on the use of foreign advertisements in the classroom and student reactions to them.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The growing reality and awareness that humans live in a globalizing world has created a need for innovative teaching methods that can help students relate to and understand other cultures and peoples (Albers-Miller, Prenshaw, & Straughan, 1999; Ortiz, 2004). Yet, as Munoz, Wood, and Cherrier (2006) recognized, teaching intercultural proficiency in a traditional classroom setting can be challenging; students learn best not from abstract discussions but from concrete examples and actual or simulated experiences in interact-ing with other cultures. Masterinteract-ing intercultural skills and attitudes is increasingly important for students entering the contemporary business world in which the ability to accept and interact effectively with diverse cultures is becoming a critical and valued skill (Jones, 2003). Cox (1991) added that the ability to work effectively in a multicultural en-vironment is based on an individual’s worldview and the ability to accept differing perspectives, ideas, and behavior. Although it is widely acknowledged that intercultural sensi-tivity is crucial in enabling individuals to live enjoyably and to work productively in other cultures (Anderson, Lawton, Rexeisen, & Hubbard, 2006), the means and methods for im-parting the needed cultural skills remain a major challenge that few programs can claim to be meeting in a satisfactory manner.

Although there are certainly no panaceas for quickly over-coming the mindsets of insular students, there are numerous materials, approaches, and exercises that, if used creatively, can help students to gain glimpses of how other individuals think of themselves and see their worlds. The particular ex-ample cited here, the www.culturepub.fr Web site, is one I used in marketing courses in Europe and the United States. The purpose in using it is to cause students to ponder how and why products are marketed in particular and often very different ways to consumers in various parts of the world. Aaker and Maheswaran (1997) showed that national culture has a strong impact on the process of persuading consumers and also in shaping the pattern of emotions they feel in re-sponse to advertisements. The implicit contrast in the minds

of student—one which the instructional exercise seeks to make explicit—is the difference between the approach used in the economy they know best (typically, the United States in courses taught in this country) and the country shown in the video clips from the culturepub.fr site.

Making use of advertisements to expose students to other cultures is by no means a new practice in teaching interna-tional marketing and internainterna-tional business. Web sites such as Adforum.com have been used for years. The innovation that Web sites such as culturepub.fr introduce—in addition to be-ing free of charge—is that they allow professors to search for advertisements on the basis of a wide range of attributes such as humor, genre, nationality, product, brand, and popularity. The useful search features of culturepub.fr allow professors to search for highly specific and targeted advertisements to illustrate their lectures.

This approach is simple and easy to use, but requires that instructors have a smart classroom with a reliable projector and sound system as well as a fast Internet connection. It simply involves showing students advertisements from other cultures and opening a dialogue on why these advertise-ments take the particular forms and show the content that they do. Although culturepub.fr is in French, an English-language shell for the site can be accessed through AOL video by entering the term “channel:Culturepub” into the site’s search engine. The culturepub.fr Web site can also be searched in English by adding the term “channel:Culturepub” to each search query on AOL video. Culturepub.fr is the Web site for a highly popular and long-running program on French television that is devoted to examining advertisements from other countries. Culture Pub was first broadcast on the French TV station M6 in 1989. The TV show, owned by CB News, launched a Web site in 2007 to allow viewers to watch their favorite foreign advertisements online. Accord-ing to culturepub.fr, the Web site receives 4.6 million hits per month.

As already noted, culturepub.fr is in French. Although it is not essential to have a mastery of French to use the site, some knowledge of the language greatly facilitates the task. A useful feature for individuals who are challenged by their limited knowledge of French is the fact that the most popular advertisements are displayed on the homepage. Often useful examples can be found simply by opening the home page, without having to explore the site more deeply. Within the site, users can search for advertisements in a number of ways. They can bring them up by genre, age, product, theme, and nationality. Other sites such as YouTube also have examples of foreign advertisements but their selection is less broad and varied. Indeed, the advertisements on YouTube seem to have been selected precisely because they appeal to Amer-ican users. Although that may be logical for maximizing audiences, it works against the purpose pursued here—that of opening minds to foreign cultures through the display of advertisements that initially may seem puzzling or even imponderable.

WHY FOCUS ON ADVERTISEMENTS?

It can be considered that advertisements offer a rather limited and superficial insight into culture. Why not analyze news-paper stories, editorials, or other more serious materials? In fact, the cryptic nature of advertisements, their use of innu-endo, their evocation of shared experiences and values, and their easily perceived if artfully disguised goals make them an especially useful medium for peeking into other cultures and pondering the concerns and aspirations that drive them. Typ-ically, the message contained in an advertisement is simple and direct; the context is usually only hinted at as the view-ers are expected to supply it from their own cultural stores. It cannot, of course, be assumed that students will quickly get the message in a foreign advertisement or even with coach-ing interpret it in the manner intended by those who create or sponsor them. Their reaction is often one of puzzlement or amusement and the explanations they offer of the messages disguised in the advertisement frequently miss the point com-pletely. Generating this uncertainty is an essential value of the exercise. In order that they may gain cultural understand-ing, it is often necessary to begin by putting learners in a state of befuddlement. Learners need to recognize that they either do not understand a message or are in considerable doubt as to what its true meaning may be and why the presentation takes the form that it does. It is often helpful to ask students to recall advertisements for similar products in the culture they know best and to then invite them to speculate on why another culture would take a very different approach to accomplish a similar or identical purpose: the marketing of a particular product. This in effect is a way to help students understand culture by proceeding from the specific to the general rather than, as is usually done, by offering general explanations of cultural variations and seeking examples to illustrate them. It is not contended here that inductive approaches are always superior to deductive ones, but that cultural generalizations should normally be supported with realistic examples that provide an insight into the subtle and ambiguous nature of the cultural differences being illustrated. The critical exam-ination of foreign advertisements is not, of course, an end in itself, but a way of cautioning students that the traditional lenses through which they perceive reality may be misleading when applied to other cultures. The lesson is not to beware of what your eyes and ears tell you, but to reflect more deeply on how the sensory information received is to be interpreted. Often there is no single or unambiguous interpretation of a particular advertisement. In fact, the target viewers (e.g., Thais in Thailand) may offer a variety of interpretations of the content and strategy of the same advertisement. By its very nature, culture is often ambiguous and subtle. The goal is not to enable students to expertly interpret other cultures—that is expecting far too much—but to make them more conscious and reflective about the need to approach other cultures cau-tiously and sensitively and to encourage them to test their assumptions carefully before they act on them.

Classroom Presentation

Evidently, there is no standard formula for using the mate-rials on the Web site in the classroom. It is probably bet-ter that the pedagogical approach changes to some degree each time an advertisement is introduced. Initially, the in-structor should simply ask the class to respond to the pro-jected advertisement. This usually elicits a great variety of views and often a good deal of controversy and discussion. It could then be focused in on what the differences (as com-pared with an American advertisements for a similar product) may be and how such differences might be explained. Such structured comparisons clearly require and bring forth more thought and analysis than does an open discussion. It can be useful to seek to classify the points as they are made and to list them on the board in order to make the differences explicit.

On other occasions, the exercise would be handled more formally. After watching an advertisement, students would be asked to note down on a sheet of paper (a) what they found most striking or, in some cases, troubling in the advertise-ment; (b) how the presentation differed from their expecta-tions, usually based on how similar products are advertised on television in the United States; and (c) what factors—cultural, political, developmental—they felt could explain the per-ceived differences. Customarily, students would be given about 10–15 min to complete this exercise.

These more considered accounts of the form of the ad-vertisements and the messages contained in them are usually more varied and generally far more thoughtful and insightful than those resulting from an open discussion. Indeed, many students observed that discussions based on these more care-fully considered accounts were more animated and valuable than earlier discussions based on mere brainstorming. In part, this was because students found themselves with positions or interpretations to defend. American students have generally been raised with the belief that collective wisdom derives from a spontaneous sharing of views; European and Asian students, by contrast, are more likely to wish to reflect on issues before expressing themselves on them publicly. By using and comparing both approaches, students gain further insight into important ways in which cultures differ.

These are obviously exercises in which there is no right or wrong answer. Their purpose is to show that meaning is often contingent on cultural context and understanding. In a typical course, 30 or so advertisements can be used during an academic year. In the session in which advertisements are first introduced, a detailed explanation regarding their pur-pose and intended value is offered. The author of this article usually integrates the explanation into a showing of ten to twelve advertisements selected to illustrate the points being made. In subsequent sessions, the instructor will as a rule use only four to six advertisements selected to illustrate par-ticular points. These subsequent sessions are shorter a half an hour or so—and serve to reinforce the need for students

174 J. RYAN

to develop their cultural awareness and interpretive skills. Instructors ought to be conscious of the danger of overkill. The first advertisements shown always provoke a strong re-action and high interest from students. This interest, alas, can diminish quickly unless efforts are made to keep the discus-sion focused and make it as penetrating as possible. While often surprising and unusual, the advertisements must not be presented as simple curiosities: “How strange those folks are and what odd tastes they have?” The analysis must be focused on trying to understand what is being presented and why it is being done in the manner that it is. Although there is no place for dogmatism in offering interpretations, there is also little value in projecting advertisements if students simply observe without reflecting on the purpose, content, and strategies embodied in them. In brief, the Web site is not self-instructional, but rather presents a valuable collection of learning materials that can be used to good effect when skillfully integrated into a marketing or business curriculum.

Three Selected Examples

Three examples of advertisements taken from the www.culturpub.fr are presented below. The first, for Smooth-E Babyface Cream, is intended to suggest how advertising is affected by the aesthetic values and cultural images pre-vailing in a society. The second and third examples show the very different ways in which the same products are sold in different cultures: Heinz ketchup in the first example and Apple’s iPod in the second.

Smooth-E Babyface cream. This is a facial cream, produced and sold by a Thai company named Smooth-E Ltd. It is marketed through a commercial that takes the form of a soap opera: girl sees and seeks boy; girl is initially ig-nored by boy; girl then finds and uses Smooth-E Babyface Cream; boy is smitten by her glowing complexion. The story has many amusing and unpredictable twists, but the moral is that improving your complexion with Smooth-E Baby-face Cream improves your chances in life and help you find love. Apart from the crassness and the claimed supernatural powers of the cream in question, this is a universal fable. What makes it Thai is that the aesthetic is Thai; the girl’s beauty is one that Thai culture venerates, especially light and clear skin. This has social importance in societies where, un-til quite recently, the majority of women and men worked in agriculture, exposed to a searing sun. The name of the cream, of course, must be in English. The implication is that it is not a traditional product, but rather a product based on the same high technology that makes Hollywood stars glam-orous. In many cultures, a baby’s skin is a symbol of beauty: individuals enter the world in a state of perfection, but then the slings and arrows of a harsh and demanding life take their toll. Smooth-E Babyface Cream, it would seem, can remove the dents and dings of life and return its users to their original pristine state. According to the Smooth-E Web site,

“the Smooth-E customer is a modern, educated, image and health-conscious person.” In this instance, the Thai approach to advertising beauty products differs markedly from the ap-proach generally used in North America and Europe where the pretentions and benefits of products are presented boldly but more modestly and realistically.

The discussions this advertisement spark are usually far-ranging as, What is beauty? What is the status of women suggested by such advertisements? Is it ethical to oversell such products by suggesting they are a key to beauty? What mystical powers does popular culture in developing nations attribute to the West? What accounts for the power and mys-tique of the West? Is fact-based advertising more or less ef-fective than suggestive advertisements that impute marvelous qualities to quite ordinary goods and services? What control, if any, should public authorities have to monitor, correct, and punish such misrepresentations? Obviously, these questions cannot be adequately explored on the basis of the informa-tion stated or suggested in a brief advertisement alone. Such advertisement do, however, open the classroom to a set of issues that compel students to reflect more deeply on other cultures and in doing so perhaps gain some insights into their own. Many of the issues raised, although perhaps not directly relevant to a traditional marketing curriculum, are components of the type of liberal arts education that future business leaders require. They teach learners to look beyond immediate purposes—selling a product—to the underlying social consequences and implications of such actions.

Heinz ketchup. Another useful approach involves tak-ing the same product and observtak-ing how it is advertised in different cultures. One site, for example, shows how Heinz ketchup and soups, products very familiar to Americans, are advertised in three other cultures: India, the United States, and Germany. In all three countries, Heinz makes humor one of the central themes in its advertisements, but it emphasizes different product attributes in each market. In India, for ex-ample, the emphasis is placed on the premium nature of the product and its thickness. The fact that Heinz ketchup does not gush out of the bottle, but has to be coaxed out with taps and squeezes is one of the central points in the advertisement. This may be necessary because Heinz competes with Indian products, such as Kissan ketchup, that are generally priced much more affordably and have a more liquid consistency. In order to justify its premium price, Heinz has to insist that its product is purer, thicker, and more chic. This better mouse-trap approach suggests that the disparity in quality of the products more than offsets the important difference in price. In the United States, contrastingly, Heinz ketchup advertise-ments focus on the flavor of the product and the fact that it enhances ordinary food. The Heinz advertisements from Germany and other European countries emphasize the con-venience and flavor of Heinz products. There the focus is usually not on ketchup exclusively, but on sauces and soups. This may be because the European market for ketchup is both

limited and mature, compelling Heinz to diversify its product range in order to grow sales. Advertisements, although they must be sensitive to cultural and the ways in which products are used and regarded in different cultures, are primarily in-struments for serving commercial and economic goals and strategies.

Apple iPod. Another product for which advertisements from more than one country are shown is the Apple iPod. The culturepub.fr site has iPod advertisements from Ger-many, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Although the British and American iPod advertisements are quite sim-ilar, the German one is markedly different. The American and British ads focus heavily on the trendiness of the product and the fact that it has strong associations with the world of hip hop. The advertisements resemble music videos. The German advertisement, on the other hand, makes a mockery of the fact that the iPod is perceived as a trendy accessory by using a tall, lean, loud, obnoxious actor dressed in white and silver to represent the iPod. The product itself is never actu-ally shown in the advertisement. Does this show a German proclivity to favor fantasy over literal presentations—an ac-tor representing the phone and not the phone itself—whereas Anglo-Saxon cultures might seem to favor more literal rep-resentations? The iPod actor is paired with an overweight, middle-aged iPod user. The contrast between the tall and lean iPod actor and the short and stout iPod user is vivid. The in-tent of the advertisement is both to mock and simultaneously emphasize the idea of the iPod as a fashionable accessory. This advertisement is careful to stress the technical merits of the product: It is effectively the Porsche of its field—a sleek and stylish companion, but also a proficient technical masterpiece. The assumption here would seem to be that the German consumer is more technologically exigent than his American or British counterparts. There is a German saying that a spring cannot be judged by a swallow. Students should be reminded of that expression. If cultural stereotypes need to be drawn, they should be penciled in until confirmed by subsequent experiences.

METHOD

To assess the effectiveness of using foreign advertisements in lectures, and to collect feedback, I circulated a question-naire to 110 undergraduate students in six sections of a global marketing course taught between the spring semester of 2008 and the spring semester of 2009 at a university in California. Students were asked for their views on two subjects relating to the foreign advertisements shown in class. The first ques-tion, scored on a 10-point scale, was whether they had found the exposure to and analysis of foreign advertisements useful in gaining insights into foreign cultures. All students scored the utility of the exercise at 5 (useful) or above.

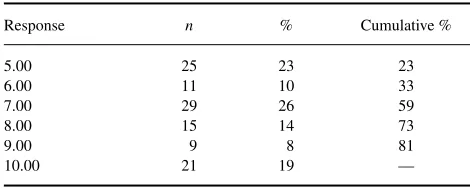

TABLE 1

Usefulness of Advertisements for Understanding Other Cultures (N=110)

Response n % Cumulative %

5.00 25 23 23

6.00 11 10 33

7.00 29 26 59

8.00 15 14 73

9.00 9 8 81

10.00 21 19 —

Note.Results are rounded to the nearest percentage point.

FINDINGS

As shown in Table 1, 59% scored the usefulness of studying the advertisements at 5, 6, or 7 and 41% assigned a score of 8, 9, or 10.

Table 2 displays the responses of students when asked to rate the degree of difference between American and for-eign advertisements on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (little difference) to 5 (extreme difference). As can be observed, over 70% of students rated the differences as highly significant (4) or extreme (5). None of the students considered the differences to be minor or insignificant.

DISCUSSION

It must be noted that the sample size is relatively small (110 cases), all collected from a single University in California campus. If the different findings were small and subtle, they could easily be attributed them to sampling error. But on both of the issues discussed previously, student opinion was close to unanimity. All students considered the presentation and discussion of foreign advertisements to be of use to them in seeking to understand other cultures: rating the utility 5 or higher on a 10-point scale. On the second issue, the perceived difference between American and foreign advertisements, 106 out of 110 students rated the degree of difference as 3 or higher on a 5-point scale. Roughly three quarters of the 110

TABLE 2

Degree of Difference Between American Advertisements and Foreign Advertisements

(N=110)

Response n % Cumulative %

2.00 4 4 4

3.00 24 22 26

3.50 3 3 29

4.00 30 27 56

5.00 49 44 —

Note.Results are rounded to the nearest percentage point.

176 J. RYAN

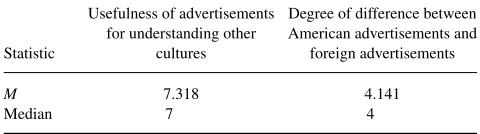

TABLE 3

Mean and Median Scores for Both Questions

Statistic

Note. N=110 for both questions.

students (79 out of 110) considered the advertisements to be either “very different” or “completely different” from the advertisements presented on American media (see Table 3). In sum, the survey strongly suggests that for a small sample of students at least, the exploration of foreign advertisements developed an enhanced awareness that different cultures ap-proach similar issues—how to market product X or Y—in very different ways.

The value they found in the examination of advertise-ments stemmed mainly from the degree of difference in the approaches taken by foreign advertisements as compared with American advertisements. Indeed, in discussions with students, the point that was emphasized was the value students found in not only observing striking differences, but also in being pushed to analyze and explain such differences. To be sure, an awareness of differences does not permit an individual to fully understand or make practical use of different advertising idioms, but it does caution students that their instincts and tastes are the products of their experiences and values and that others, building on their own experiences and values, may see the world quite differently. Although it would be a gross exaggeration to maintain that an understanding of other cultures can spring from a few classroom exercises, they can launch and advance that process by eroding cultural egocentrism. This is a limited but nonetheless important and necessary step in preparing culturally aware students for a global economy.

CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The need to prepare students to understand their roles as responsible world citizens and effective business profession-als in an increasingly integrated and interdependent global economy and society is one of the major challenges con-fronting education in the 21st century. This paper sets forth a modest proposal—one that is virtually cost-free and demon-strated to motivate and draw students out about how to ad-vance the international awareness and sensitivity of under-graduate marketing students through the use of a Web site (www.culturepub.fr) featuring foreign advertisements. The empirical data cited on student evaluations, while based on a small and limited sample, strongly indicates that a sample

of undergraduate students in the United States found exam-ination of foreign advertisements both insightful and use-ful in stretching their cultural perceptions. Lastly, it should be emphasized again that the challenge of preparing stu-dents to understand and act effectively and responsibly in the emerging global village must become an increasingly central element in business education and, indeed, in the liberal arts curriculum. Exercises such as that suggested here if used intelligently can assist in developing cultural sensitivity and understandings, but the overall challenge cannot be met by any single exercise or class. Developing international and cultural understanding must be understood as an overarching educational objective to which all aspects of university life and study should contribute.

Research on the key issue of building intercultural profi-ciency is being approached from a number of directions, as is necessary and appropriate given the complex and multi-faceted nature of the issue. Developing the ability to perceive and act upon realities in a culturally sensitive and effec-tive manner should be conceptualized as a long-term process to which numerous experiences can contribute (e.g., study abroad programs).

Studies of cultures and a wide-range of special interven-tions, such as that discussed previously. Although even mod-est initiatives are needed and should be welcomed, the main thrust of further research should concentrate not on single interventions, but rather on combinations of different ap-proaches. Measures such as Hett’s (1993) global-mindedness scale and Olson and Kreuger’s (2001) intercultural sensitivity index provide promising tools for measuring the development of different aspects of intercultural proficiency over time and in relation to particular experiences. Longitudinal studies that examine the growth of cultural competence from entry into university until graduation would shed useful light on the value, variety and sequencing of different instructional and experiential approaches in enhancing the cultural sensitiv-ity, intercultural-communication skills, global-mindedness and other key components of intercultural proficiency. As Munoz, Wood and Cherrier (2006) rightly note, the pro-motion of cross-cultural understanding and competency is a subject that urgently requires cross-cultural collaborative exercises and careful investigation of pedagogical methods capable of opening minds to new worlds, different peoples and the full range of cultural experiences. While it is fitting that we should set ambitious goals, it is also important that we remain mindful of the limited means that both students and academic programs possess in this season of austerity. Thus it is important that we search out resources and approaches that are economical as well as effective. It has been argued that the approach suggested in this paper is successful on both scores. The Web-based resources are free; they can be fitted into normal classroom activities and if used skillfully, they push students outside of their normal frames of refer-ence and expose them to the realities of other cultures and societies.

REFERENCES

Aaker, J., & Maheswaran, D. (1997). The effect of cultural orientation on persuasion.Journal of Consumer Research,24, 315–328.

Albers-Miller, N. D, Prenshaw, P., & Staughan, R. (1999). Student percep-tions of study abroad programs: A survey of U.S. college and universities.

Marketing Education Review,9(1), 29–36.

Anderson, P. H, Lawton, L., Rexeisen, R., & Hubbard, A. (2006). Short-term study abroad and intercultural sensitivity: A pilot study.International Journal of Intercultural Relations,30, 457–469.

Cox, T. (1991). The multicultural organization.Academy of Management Executive,5(2), 34–47.

Cunningham, P., & Jones, B. D. G. (1997). Educator insights: Early de-velopment of collegiate education in international marketing.Journal of International Marketing,5(2), 87–102.

Hett, E. J. (1993). Development of an instrument to measure globalmind-edness.Dissertation Abstracts International,54(10), 3724. (UMI No. 9408210).

Hise, R. T. (1991). Global geographical knowledge of today’s business students: Implications for teaching the international marketing course.

Journal of Teaching International Business,3(1), 65–86.

Hise, R. T., Davidow, M., & Troy, L. (2000). Global geographical knowledge of business students: An update and recommendations

for improvement. Journal of Teaching International Business, 11(4), 1–22.

Hise, R. T., Sin, J., Davidow, M., Fahy, J., Solano-Mendez, R., & Troy, L. (2004). A cross-cultural analysis of the geographical knowledge of U.S., Irish, Israeli, Mexican, and South Koreans.Journal of Teaching International Business,15(3), 7–26.

Jones, W. H. (2003). Over the wall: Experiences with multicultural literacy.

Journal of Marketing Education,25, 231–240.

Munoz, C. L., Wood, N., & Cherrier, H. (2006). It’s a small world after all: Cross-cultural collaborative exercises.Marketing Education Review,

16(1), 53–57.

Olson, C. L., & Kroeger, K. R. (2001). Global competency and intercultural sensitivity.Journal of Studies in International Education,5, 116–137. Ortiz, J. (2004). International business education in a global environment:

A conceptual approach.International Education Journal,5, 255–265. Thanopoulos, J, & Vernon, I. (1987). International business education in

the AACSB schools.Journal of International Business Studies,18(1), 91–98.

Turley, L. W., & Shannon, R. (1999). The international marketing cur-riculum: Views from the students.Journal of Marketing Education,21, 175–180.

Tyagi, P. K. (2001). Internationalization of marketing education: Current status and future challenges.Marketing Education Review,77(1), 75–84.