Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 22:53

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Leadership Development as a Systematic and

Multidisciplinary Enterprise

Stacey L. Connaughton , Francis L. Lawrence & Brent D. Ruben

To cite this article: Stacey L. Connaughton , Francis L. Lawrence & Brent D. Ruben (2003) Leadership Development as a Systematic and Multidisciplinary Enterprise, Journal of Education for Business, 79:1, 46-51, DOI: 10.1080/08832320309599087

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320309599087

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 199

View related articles

as

Leadership Development

Systematic and Multidisciplinary

Enterprise

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Most men and women

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

go through theirlives using no more than a fraction- usually a rather small fraction-of the potentialities within them. The reservoir of unused human talent and energy is vast, and learning to tap that reservoir more effectively is one of the exciting tasks ahead for humankind.

-John Gardner, On Leadership, 1990

fforts to develop the human poten-

E

tial for leadership have become an increasingly popular theme within recent years. Although this goal is a noble one, those dedicated to this purpose, in higher education and other organizational set- tings, have come to recognize the consid- erable challenges in providing education- al experiences that help learners effectively translate visions and concepts of leadership into practice. Indeed, after conducting an extensive review of corpo- rate training and development programs that focus on communication abilities, interpersonal skills, and leadership com- petencies, the Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organiza- tions concluded that corporations wastebetween

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

$5.6 andzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

$16.8 billion each yearon ineffective leadership training pro- grams (2002).

One of the fundamental reasons for these programs’ inadequacies is their short-term, isolated approach to devel- oping leaders. Simply put, it is unrealis- tic to expect that enhanced leadership

STACEY L. CONNAUGHTON

FRANCIS L. LAWRENCE

BRENT D. RUBEN

Rutgers University

New Brunswick, New Jersey

ABSTRACT. Leadership develop- ment is a fundamental responsibility of colleges and universities. In this article, the authors present the theoret-

ical foundation of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an innovative initia-tive, as well as criteria for assessing leadership development programs in higher education. They use the Stu- dent Leadership Development Insti- tute at Rutgers University as a case study for demonstrating that leader- ship development initiatives should be systematic, multidisciplinary, and research oriented and have several experiential components.

capabilities can be developed in a 2-hour or even a week-long leadership work- shop. Rather, leadership competencies are best developed over time through a program that fosters personalized inte- gration of theory and practice and that conceives of leadership development as a recursive and reflective process. There- fore, in this article we argue that colleges and universities have a fundamental responsibility to guide the development of the next generation of capable and ethical leaders and that these institutions must do so through a highly focused, multidisciplinary approach.

Leadership Education :

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A Necessity

The influence of market economics, the proliferation of technology, and the emergence of new democracies charac- terize the global arena at the dawn of the

21st century. It is impossible to deter- mine precisely what knowledge and competencies will be required to address the opportunities and chal- lenges of our rapidly changing interna- tional environment. It is certain, howev- er, that leadership competencies will be increasingly essential in the United States and around the world.

Yet disaffection and cynicism about leaders and leadership are apparent in many spheres: business, politics, the nonprofit arena, even the formerly sacro- sanct religious institutions. Some of the most admired organizations in our soci- ety have been tarnished by leadership problems; some were badly mismanaged by individuals incapable of dealing with changing external circumstances, and others were sullied terribly by those who betrayed the public’s trust after abusing the responsibilities of their posts.

Given this climate, leadership educa- tion is a necessity. An educated citizen- ry is the most coveted, vigorously culti- vated, and dependable national resource, and higher education rapidly is becom- ing a requirement for full participation in societies today. In the United States,

63% of high school graduates now go to

college, and exponential growth is also occurring abroad. In the United King- dom, just between 1989 and 1995, the number of full-time students increased by almost 70% (Scott, 2001). Australia

46 Journal of Education for

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Businesssaw an increase of 30% in the number of students participating in higher educa- tion over the decade of the 1990s (Com- monwealth of Australia Department of Education, Science, and Training, 2002). And China reports that from 1979 through 1997, more than two and a half times more students than in the pre- vious 30 years completed junior college and bachelor’s programs (China Educa- tion and Research Network, 2003). To

navigate the world’s ever-changing eco- nomic, technological, social, and politi- cal dynamics, and to overcome the cyn- icism frequently associated with private- and public-sector leadership, citizens must become better educated to fulfill leadership challenges responsibly, effec- tively, and ethically.

Although our institutions of higher education have produced many articu- late, principled, and effective leaders, it is not difficult to point to graduates of respected institutions who provide spec- tacular examples of failures in judgment and integrity, and more generally in the execution of their responsibilities as leaders. The unmistakable conclusion is that when it comes to leadership devel- opment in higher education, “business as usual” is insufficient. A smattering of classes related to leadership, a com- mencement address on ethics, a week- end retreat on leadership, or limited involvement in community service can be important components in the leader- ship development equation, but they are not sufficient in isolation.

To meet the leadership development challenge, colleges and universities must be considerably more proactive and systematic in their leadership edu- cation efforts. As a foundation, it is vital to collect and synthesize the various dis- ciplinary perspectives on leadership, identify the competencies necessary to the practice of effective leadership in varying contexts, and determine the appropriate blend of pedagogical meth- ods by which theories and competencies

can be taught and learned best.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Theoretical Foundation for Leadership Development Programs

When it comes to reading about lead- ership, interested parties are not at a

loss for material. Indeed, a plethora of academic and popular press literature about leadership exists. Yet selecting and synthesizing appropriate concepts, assumptions, and frameworks offered by various disciplinary perspectives is a difficult and highly subjective undertak- ing. Seeking to be multidisciplinary in scope, the Student Leadership Develop- ment Institute (SLDI) at Rutgers Uni- versity serves as a case study that draws from concepts and perspectives from the behavioral sciences, ideas from organizational and communication studies, and thoughtful reviews and analyses of professional practice. For our present purposes, we identify nine principles that buttress and give coher-

ence to the SLDI educational initiative:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

First, leadership is complex. This is true

whether one

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

thinks of leadership in the- oretical or pragmatic terms. Contribut-ing to this complexity are the many fac- tors and dimensions associated with a leader, followers, and the situation, as well as the goals, strategies, and culture

of the unit (Bennis

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Thomas, 2002; Hughes, Ginnett, & Curphy, 1993). Thecomplexities of leadership help explain why there are so many definitions of leadership-a fprther source of com- plexity. Some definitions focus on lead- ership roles or positions, others empha- size leadership outcomes, and still others focus on leadership styles and strategies.

Second, leadership

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

is other-oriented. Acommon theme in most definitions of leadership is the recognition that leader- ship is related to others. At various points in time, leadership may involve serving others (Greenleaf, 1977; Spears, 1998), influencing others to achieve a common goal (Bennis, 1997), coordi- nating and direkting others (Fiedlqr, 1967), understanding and inspiring oth- ers (Bass & Avolio, 1994), connectiqg others (Lawrence & Cermak, 2003; Lip- man-Blumen, 2000), and other activi- ties. Common to all definitions is a recognition that leaders work with and through others, an essential component to successful leadership practice.

Third, leadership is interactive and dynamic. Leadership is not character- ized by a single or static action, but

rather by an ongoing process of interac- tion between leaders and followers. Burns (1978) noted that these interac- tions may take two forms. Sometimes leaders and followers interact to exchange valued commodities, either tangible or symbolic (what Burns calls “transactional leadership”). Other times, “leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality.

.

. .

Their purposes. .

.

become fused” (Burns’s notion of “transforming leadership,” explained in Bums, 1978, p. 20). During this latter interaction, followers may transform leaders just as much as, if not more than, leaders transform followers. In agreement with Burns, we argue in this article that leader-member relationships are embedded in expectations, values, and systems of power that influence interactions over time.

Fourth, leadership is contextual.

Although leadership often is discussed in the abstract, leadership in practice occurs in a specific context. That is, leadership takes place in a particular sector-business, health care, govern- ment, or education, for instance. And organizations themselves provide a fur- ther contextual framework that is important to leadership. Each organiza- tion has a particular mission, a set of aspirations and values, history, rituals, roles, and a unique culture, all of which relate to leadership. Indeed, as Bass noted, “the meaning of leadership may depend on the kind of institution in

which it is found” (1995, p.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

38). At the very least, leadership practices must beadapted to the context and people that an individual is leading.

Fifth, leadership may be emergent. In many organizations, some leadership roles are structurally defined; individu- als who occupy positions carrying the title of CEO, director, or manager are often expected to be leaders. However, leadership opportunities-and often positions-may emerge within organi- zations. Such is the case with project teams and task forces. In cases in which no formal leader is designated, leadership is wholly emergent (e.g., self-managing teams; see Manz &

Sims, 1987). And at times, ordinary

September/October 2003 47

citizens may be prompted to do extra- ordinary things, emerging as citizen

leaders (Cuoto, 1992).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Sixth, leadership is a science and an art.Although leadership is viewed appropri- ately as an area for social scientific inquiry and theoretical development, the practice of leadership is, to some extent, an art. That is, each leader must learn to apply available theory and research findings in a way that is compatible with his or her own personality, skills, experience, values, capabilities, goals, and contextual assessment. One impli- cation of this way of thinking is that there is no universal leadership ap- proach that should be taught and learned by all (Tichy, 1997), a conclusion that challenges leadership educators. There- fore, leadership development programs must integrate systematically the scien- tific study of leadership and the applied, subjective, and personalized aspects, through a recursive and reflective learn- ing process that leads to a personalized integration of theory and practice. Seventh, leadership is enacted through communication. Communication plays a fundamental role in leadership. The behaviors associated with leadership are, in the final analysis, communication behaviors. Leaders not only conceive of a vision, but they must articulate it to others; leaders make decisions, but they must first interact with others to gather needed information and leverage sup- port. Indeed, leadership is displayed and enacted through an individual’s verbal, nonverbal, and technologically mediated behaviors (Witherspoon, 1997). This collective set of communication behav- iors provides the basis for reputation,

credibility, and influence (or lack there-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of), all of which are of fundamental interest to leadership study and practice. Eighth, leadership is increasingly medi- ated and virtual in nature. There was a time when much of the work of leader- ship occurred in face-to-face settings. To- day, however, leaders in many sectors and organizations interact with col- leagues who are separated by time and space (Connaughton & Daly, in press). Communication technology+ll phones, pagers, e-mail, video conferencing, list-

servs, chat rooms, intranets-supple- ment, and sometimes nearly replace, co- located leadership. Given these circum- stances, competence in the use of technology for interaction (among other competencies; see Connaughton & Daly,

in press) is

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an important component of leadership expertise.Ninth, leadership can be learned and taught. One of the most fundamental principles governing leadership educa- tion initiatives is that leadership can be learned and taught. Scholars and educa- tors have not always made this argu- ment, however. In some early writings, for instance, leadership was viewed as a static trait (see Stodgill, 1948). Others viewed leadership as linked naturally and necessarily to cognitive ability or general educational accomplishment. We argue, however, that leadership competencies do not develop automati- cally as a consequence of having partic- ular cognitive capabilities or discipli- nary expertise. As with musical, ath- letic, and other performance competen- cies, the requisite knowledge and skills for leadership can be taught and learned, and leadership studies is an area of academic inquiry and applica- tion in its own right (Connaughton &

Quinlan, 2003; Ruben, 2003). In mak- ing this point we join other leadership scholars, among them James MacGre- gor Burns (1978), Daniel Goleman (1997, 1998a, 1998b), Peter Vail(1998),

and Howard Prince (2001).’

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Benchmarks for Leadership Development Programs in Higher Education

Although we benefit from exemplary models of leadership development in both higher education (e.g., U.S. Military Academy; see McNally, Gerras, &

Bullis, 1996) and in corporate America (e.g., General Electric; see Melum,

2002), we lack a complete theory of how to develop leaders. Until we learn the results of longitudinal studies of lead- ership development currently under way at Alverno College, Yale University, and the U.S. Military Academy (Horvath, Forsythe, Bullis, Sweeney, Williams, McNally, Wattendorf, & Sternberg, 1999; Mentkowski & Associates, 2000),

we must rely on the experiences and reflections of those who have led and been engaged in student leadership development.

Prince (2001) outlined four criteria that a leadership development program must consider. First, the faculty’s teach- ing methods must match the desired outcomes. Our primary goal is to devel- op leaders, and such a goal necessitates using more than a traditional lecture classroom format. The specifics of such teaching methods are revealed in Prince’s other criteria. Second, learning opportunities must be created to allow students to apply and practice their knowledge and to experience the conse- quences of their actions. Situations must be created that allow students to receive feedback on their leadership processes both inside and outside of the class- room. Third, students must be strongly encouraged to reflect on and discuss their leadership experiences with facul- ty members and peers. In establishing these criteria, Prince cited Mentkowski and Associates (2000), who reported on early results from a longitudinal leader- ship development study at Alverno Col- lege. They found that reflection is es- sential for integrating knowledge, experience, and character. And fourth, students must have vicarious learning opportunities. Students learn from more experienced leaders by listening to and interacting with them. As we reveal in the next section, the Rutgers model fits these criteria.

Preparing the Next Generation

of Leaders

Using the Student Leadership Devel- opment Institute (SLDI) at Rutgers Uni- versity as a case study clarifies the process of preparing the next generation

of leaders. The SLDI is

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

a dedicated lead- ership development initiative for under-graduate students. The institute has five objectives: (a) to ground students’ com- prehension in the academic study of leadership theory; (b) to foster opportu- nities for students to develop leadership competencies while working on projects of social and civic consequence; (c) to enable students to network with peers, experts, and organizations; (d) to encour- age students to reflect on their own

personal leadership philosophy and experience; and (e) to attract national and international leadership experts from academia, politics, government, nonprof- it, and for-profit organizations to Rutgers for colloquia and conferences. The initia- tive aims to enhance significantly the education of the next generation of lead- ers through a rigorous multidisciplinary program in cooperative, interactive, and ethical leadership. In doing so, SLDI links traditional academic education with experiential and application-oriented in- structional methodologies.

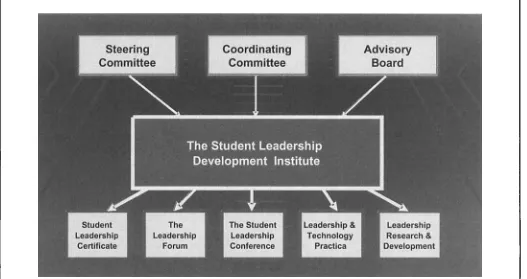

There are five components to the institute’s leadership development pro- gram (see Figure 1). The first is the Stu- dent Leadership Certificate. Designed to begin during a student’s sophomore year, the 15-credit program combines credit-bearing course work in leadership studies with cocurricular leadership experiences and participation in annual leadership conferences. It enhances stu- dents’ leadership competencies and experiences through theoretical and applied course work, internships, and interaction with leaders from business, education, health care, and government and provides a formal leadership certifi- cate upon its completion.

The second component, a Leadership Forum, has two dimensions. The first is a public lecture series in which senior leaders from the public and private spheres share their insights and experi- ences with students and community members. They discuss topics of impor- tance to contemporary leadership and organizational development, such as knowledge networking, ethics, organiza- tional culture, institutional change, lead- ership styles, work-life balance, and organizational assessment and change. The second dimension, the Roundtable, consists of smaller luncheon meetings in which invited students and faculty mem- bers have the opportunity to continue and deepen their dialogue with the speakers. The third component, the Student Leadership Conference, is planned and led by certificate students and is open to all students. The conference brings together students, faculty members, staff, and practitioners in a high-profile univer- sity event. It has two objectives: (a) to give students opportunities to discuss leadership topics with individuals out- side of the classroom and (b) to enable students to put their leadership skills into practice by organizing the conference. The 1 -day conference includes a keynote

address by a prominent scholar or practi- tioner, breakout sessions in which stu- dents work together on activities related to specific leadership issues such as con- flict management and team building, and special presentations by students on lead- ership class projects.

The fourth component, the Leadership and Technology Practicum, enables stu- dents to develop their expertise in medi- ated communication and to create media resources related to leadership develop- ment for other students’ use. These activ-

ities and resources include

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Learning to Lead, a television program featuring theleaders who speak in the Leadership Forum on current leadership issues with students; E-Leadership, an electronic newsletter about leadership, produced by the Center for Organizational Develop- ment and Leadership, and for which stu- dents are invited to submit essays and review popular books related to leader- ship; and the Video Lecture Database, a collection of public presentations made at Rutgers by organizational leaders. These leaders include the area vice pres-

ident of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

U.S. sales for Cisco Systems,Carlos Dominguez; the former Bell Atlantic and Verizon president and chief

[image:5.612.46.573.426.705.2]operating officer, Jim Cullen; and Presi-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

FIGURE 1. The five components of the Student Leadership Development Institute (SLDI).

September/October 2003 49

dent Emeritus of Oregon State Universi- ty John Byme. Students also have access to the Integrated Leadership Web site, which furnishes information about lead- ership-related programs and events at Rutgers and elsewhere.

The fifth component, Leadership Research and Development, gives certifi- cate students hands-on leadership experi- ence. Students may work for a sponsor- ing organization as paid interns, or they may work with a faculty member and sponsoring organization on a research,

development, or educational project.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Assessment of Outcomes

The SLDI opened its doors to its first group of students in fall 2001, following a yearlong study of comparable programs offered elsewhere and an assessment of Rutgers’ needs and activities related to leadership development? Since then, the first courses have been refined, new courses have been added, and a compre- hensive approach to leadership develop- ment has evolved. In many ways, how- ever, the SLDI continues to be a work in progress, with expansion, evaluation, and continual improvement as ongoing priorities.

A comprehensive approach to evalua- tion is being developed to help in the assessment of the effectiveness of the program relative to its goals and aspira- tions. The first component of the assess- ment framework is now in place. This consists of students’ both formally and informally evaluating individual courses and instructors. Also, feedback is regu- larly gathered from student participants at various lectures, meetings, and events associated with SLDI. All such informa-

tion

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

is preliminary because of the shortperiod of time that the SDLI has been operating. In the months ahead, an attempt will be made to extend the assessment framework to identify stu- dents’ expectations at the point of entry and then track how those expectations are realized, and perhaps modified, dur- ing the course of participation.

As a part of the assessment plan, a more systematic strategy for informa- tion gathering relative to workplace leadership needs will be undertaken, building on existing literature reviews in

this area (Ruben, 2003; Ruben

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& DeAn- gelis, 1998). This information gatheringwill be in the form of surveys, focus groups, and one-on-one interviews. We also plan to initiate a systematic pro- gram of follow-up research with the SLDI program graduates.

Conclusion

Leadership development is a primary responsibility of colleges and universi- ties. The Student Leadership Develop- ment Institute at Rutgers University is one model for leadership development education that meets established criteria for such programs. In this article, we briefly have described the initiative, its theoretical orientation, and its intended impact. The SLDI represents a system- atic and proactive approach to leader- ship education, one which, we hope, will tap the reservoir of human leader- ship potential.

NOTES

1. Dr. Howard Prince is currently the director of the Center for Ethical Leadership at the Universi- ty of Texas’s Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. He was founding dean and the first facul- ty member of the Jepson School of Leadership Studies and the first head of the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

2. Support for this research and the pilot program was provided to the Center for Organizational Development and Leadership by the AT&T Foun- dation. We gratefully acknowledge their support.

REFERENCES

Bass, B. M. (1995). The meaning of leadership. In

J. T. Wren (Ed.),

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

The leader companion:Insights

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

on leadership through the ages (pp.37-38). New York: The Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. I. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transfor- mational leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bennis, W. G. (1997). Managing people is like

herding cats. Provo, UT: Executive Excellence.

Bennis,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

W. G., &Thomas, R. J. (2002). Geeks andgeezers. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: HarperCollins.

China Education and Research Network. (2003). Education evolution in China. <www.edu.cn>. Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Edu- cation, Science, and Training. (2002, April 26). Higher education at the crossroads: An overview paper: <http://www.bakingaustraliasfuture.cov.

au/publications/crossroads/defaut.htm>. Connaughton, S. L., & Daly, J. A. (In press).

Leading from afar: Strategies for effectively leading virtual teams. To be published in S. H. Godar & S. P. Ferris (Eds.), Virtual and collab- orative teams: Process, technologies, and prac- tice. Hershey, PA: Idea Group.

Connaughton, S. L., & Quinlan, M. (2003). Learning leadership competencies as campus consultants. In B. D. Ruben (Ed.), Pursuing excellence in higher education: Eight funda- mental challenges (pp. 80-87). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelli- gence in Organizations. (July 2002). <http:l/

w ww.eiconsortium.org>.

Cuoto, R. A. (1992). Public leadership education: The role of the citizen leader. Dayton, OH: The Kettering Foundation.

Fiedler, F. E. (1967).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A theory of leadership effec-tiveness. New York McGraw-Hill.

Gardner, J. (1990).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

On leadership. New York: TheFree Press.

Goleman, D. (1997). Emotional intelligence. New York Bantam Books.

Goleman, D. (l998a, Nov.-Dec.). What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review, 93-102. Goleman, D. (1998b). Working with emotional

intelligence. New York: Bantam Books. Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership: A

journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. New York Paulist Press.

Horvath, J. A., Forsythe, G. B., Bullis, R. C., Sweeney, P. J., Williams, W. M., McNally, J . A., Wattendorf, J. M., & Stemberg, R. J. (1999). Experience, knowledge, and military leader- ship. In R. J. Stemberg & J. A. Horvath (Eds.), Tacit knowledge in professional practice: Researcher and practitioner perspectives (pp. 39-57). Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hughes, R. L., Ginnett, R. C., & Curphy, G. R. (1993). What is leadership? In J. T. Wren (Ed.), The leader companion: Insights on leadership through the ages (pp. 39-43). New York The Free Press.

Lawrence, F. L., & Cermak, C. H. (2003). Advancing academic excellence and collabora- tion through strategic planning. In B. D. Ruben (Ed.), Pursuing excellence in higher education: Eight fundamental challenges (pp. 235-2421, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lipman-Blumen, J. (2000). The connective edge: Leading in an interconnected world. New York: Oxford University Press.

Manz, C. C., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (1987). Leading workers to lead themselves: The external lead- ership of self-managing work teams. Adminis- trative Science Quarterly, 32, 106-1 29. McNally, J. A., Gerras, S. J., & Bullis, R. C.

(1996). Teaching leadership at the U S . Military Academy at West Point. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 32(2), 175-189.

Melum, M. (2002). Developing high-performance leaders. Quality Management in Health Care, II( l), 55-68.

Mentkowski, M., & Associates (2000). Learning that lasts: Integrating learning, development, and performance in college and beyond. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Prince, H. (2001). Teaching leadership: A journey into the unknown. Concepts and connections: A newsletter for leadership educators, 9, 3. Ruben, B. D. (2003). Pursuing excellence in high-

er education: Eight fundamental challenges. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ruben, B. D., & DeAngelis, J. A. (1998). Suc- ceeding at work: Skills and competencies need- ed by college and university graduates in the workplace: A secondary analysis of quantita- tive and qualitative literature. Report prepared for the Conference Board, New York. Scott, J. (2001). European education reform and

developments: Impact on the relationship with

50 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessU.S. higher education.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Presentation given at the 2001 meeting of NAFSA: Association of Inter-national Educators, Philadelphia.

Spears,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

L. C. (1998). Insights on leadership. NewYork: John Wiley. York: HarperCollins. Allyn and Bacon.

Stodgill, R. M. (1948). Personal factors associated with leadership: A survey of the literature. Journal of Psychology, 25,35-71.

Tichy, N. M. (1997). The leadership engine. New

Vail, P. B. (1998). Spirited leading and learning.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Witherspoon, P. D. (1997). Communicating lead- ership: An organizational perspective. Boston: