Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 19:30

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Indonesian politics in 2010: the perils of stagnation

Dirk Tomsa

To cite this article: Dirk Tomsa (2010) Indonesian politics in 2010: the perils of stagnation, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 46:3, 309-328, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2010.522501 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2010.522501

Published online: 23 Nov 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 425

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/10/030309-20 © 2010 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2010.522501

INDONESIAN POLITICS IN 2010:

THE PERILS OF STAGNATION

Dirk Tomsa*

La Trobe University, Melbourne

In the irst year after President Yudhoyono’s re-election, Indonesian politics con-tinued to evolve in largely familiar patterns. Contrary to the expectations of some observers, Yudhoyono’s strong popular mandate and his Democratic Party’s newly won parliamentary plurality did not result in signiicant changes to the president’s cautious style of governing or the ickle nature of president–parliament relations. Most political parties also opted for continuity over change, electing or re-electing established igures as leaders despite high levels of public dissatisfaction with their performance. The fact that the 2009 election failed to generate any new momen-tum for reform does not augur well for the remainder of Yudhoyono’s second term. Although the basic parameters of Indonesia’s democracy remain intact, political developments during 2010 have also conirmed a pattern of stagnation that is likely to see Indonesia barely muddle through as a reasonably stable yet low-quality de-mocracy.

INTRODUCTION

When Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) was sworn in for his second term as Indonesia’s president in October 2009, speculation abounded among political observers as to whether his second administration would be any different from

the irst (Sukma 2009). In particular, many commentators wondered if the presi -dent would use his strong popular mandate and the newly won parliamentary plurality of his Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat, PD)1 to re-position himself as a more resolute political leader. In the previous ive years, Yudhoyono’s admin -istration had often struggled to govern effectively, especially because of the constant need for the president to secure support from a notoriously restive par-liament (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR). Apart from weak governance, other recurring problems such as endemic corruption, poorly institutionalised parties and the accommodation of powerful elite groups with questionable democratic

* This is a revised version of a paper presented to the 28th Indonesia Update conference, held at the Australian National University, Canberra, 24–25 September 2010. The author would like to thank Ed Aspinall, Marcus Mietzner, Ross McLeod and Andreas Ufen for valuable comments on an earlier draft.

1 SBY won 60.8% of the vote in the irst round of the 2009 presidential election. A few months earlier, his Democratic Party had emerged victorious in the legislative elections, winning 148 out of 560 seats in parliament (20.9% of the vote); see Sukma (2009) for further details.

credentials overshadowed Indonesia’s generally successful maturation into a

stable electoral democracy during the irst Yudhoyono term (Aspinall 2010a;

Tomsa 2010a).

One year into Yudhoyono’s second term there are few signs that much has changed. As the following overview of political developments in 2010 will show, relations between the president and the legislature are still somewhat uneasy, most political parties have done little to address long-standing problems, and several anti-democratic groups have continued to enjoy impunity despite some-times blatant human rights violations. This article will illustrate these trends of broad continuity by analysing a number of key events that shaped Indonesian politics over the last 12 months. It will be argued that, while the overall stabil-ity of the political system is not in jeopardy at this stage, the apparent inertia among Jakarta elites and their persistent unwillingness to tackle the

above-mentioned problems do not augur well for the future. Signiicantly, the irst

year of the second Yudhoyono administration has demonstrated that neither the president himself nor the parties or parliament can be expected to provide the kind of leadership required for the deepening of Indonesian democracy. The good news, however, is that civil society groups and the media have responded to the lack of initiative from Jakarta’s political elite by stepping up their efforts

to expose the country’s various democratic deicits. On balance then, political

developments during 2010 are likely to have set a pattern for the remaining years of the Yudhoyono presidency that will see Indonesia muddle through as a stable yet low-quality democracy.

The discussion unfolds in four parts. It begins with a brief recapitulation of the so-called ‘Bank Century scandal’ and the subsequent parliamentary inquiry into the case, which contributed to the resignation of one of Yudhoyono’s most

reform-oriented ministers, inance minister Sri Mulyani. After highlighting three ways in which this incident exempliied the character of Indonesian politics

throughout the year, the article looks at coalition politics and parliament–presi-dent relations in the ensuing months, especially after the formation of a joint coalition secretariat. An examination of the status of Indonesia’s political parties follows, with particular attention given to the question of leadership succession that was at the heart of several national party congresses in 2010. Finally, the analysis focuses on President Yudhoyono himself. Using as examples the Bank Century affair, the apparent rise of religious intolerance in Indonesia in the last year and the renewed tensions in Papua in recent months, the article demon-strates that Yudhoyono’s often cautious and indecisive approach to governance

is not always a virtue, but has in fact often exacerbated socio-political conlicts.

CABINET FORMATION, THE BANK CENTURY CASE AND THE DEMISE OF SRI MULYANI

First indications that continuity rather than change would mark Yudhoyono’s

sec-ond term in ofice were obvious when the president announced his Secsec-ond United

Indonesia Cabinet (Kabinet Indonesia Bersatu II) in October 2009. Defying wide-spread criticism from both the media and academic quarters, Yudhoyono once again assembled a ‘rainbow’ cabinet, with representatives from no less than six

political parties.2 In addition to his own PD, which was given six ministries, four

Islam-based parties (PKS, PAN, PPP and PKB) and the former Soeharto regime party Golkar were all awarded positions in a cabinet of 34 members.3

Grand coalitions have become a kind of ‘invented tradition’ in Indonesia dur-ing the reform era (Aspinall 2010b: 110). Ever since the short-lived administra-tion of the late Abdurrahman Wahid, Indonesian presidents have sought to win broad-based support from the country’s fragmented party spectrum by including as many parties as possible in their cabinets. The often stated and seemingly obvi-ous aim of this strategy has been to ensure smooth relations between the execu-tive and legislaexecu-tive branches of government. Indeed, given that no Indonesian president in the last 10 years has belonged to a party that held a majority of seats

in the legislature, it appears, at irst sight at least, logical for a president to try

to form such a coalition. However, a cursory glance at the history of president– parliament relations since 1999 shows that this simple calculation does not apply in Indonesia. As Sherlock (2009: 342) has explained, Indonesia’s parliament rarely makes its decisions by vote, but usually operates by consensus, so that ‘having an overall numerical majority does not necessarily translate into control of decisions

about legislation, appointment of key state oficials and oversight of executive

government spending and policy’. Moreover, cabinet solidarity has always been low across the party spectrum, regardless of how many parties have been

repre-sented in the government (Sherlock 2009; Van Zorge 2010).

It should have come as no surprise, therefore, that SBY’s large coalition began

to crumble as soon as ministers had settled into their ofices. Ostensibly, the ten -sions that erupted in late 2009 between the president and two of his ‘coalition partners’, Golkar and PKS, were triggered by alleged irregularities in the bail-out of a failed bank, Bank Century.4 It soon became clear, however, that a concern

about irregularities was not the real reason why the two parties opposed the bail-out and pushed for a parliamentary inquiry into the process. Rather, they saw an opportunity to settle some old scores with two of SBY’s most trusted aides, the

vice president, Boediono, and the inance minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati, both of

whom had played key roles in authorising the bail-out.

The Bank Century saga had begun in earnest by mid-November 2009, when 139 legislators from several parties successfully moved to set up a parliamen-tary inquiry to investigate why the amount of money used in the bail-out (Rp 6.76 trillion, or $716 million) far exceeded the original estimate endorsed by parliament.5 Leading forces behind the move were the three ‘opposition’

2 See Diamond (2009) and Sherlock (2009) for two different arguments about why rainbow cabinets are counterproductive.

3 PKS: Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (Prosperous Justice Party); PAN: Partai Amanat Nasional (National Mandate Party); PPP: Partai Persatuan Pembangunan (United Development Par-ty); PKB: Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (National Awakening ParPar-ty); Golkar: Partai Golongan Karya (Golkar Party).

4 Selected parts of the following paragraphs on the Bank Century case are taken from Tomsa (2010b).

5 For more background on the events leading up to the iling of the motion, see Patunru and Von Luebke (2010) and McLeod (2010).

parties, PDI–P, Hanura and Gerindra,6 and ‘coalition members’ Golkar and PKS.

Golkar in particular led the campaign with remarkable vigour. For the former

Soeharto regime party, which had suffered signiicant losses in the 2009 election,

the reformist Sri Mulyani had long been a thorn in the side. Well known for her tireless efforts to root out graft in her ministry, she had repeatedly clashed with the Golkar chair and former cabinet minister, Aburizal Bakrie – for example, over alleged tax evasion in some of Bakrie’s enterprises and his attitude to the

Lapindo mudlow disaster (Baird and Wihardja 2010: 144).7 Thus, after initial

attempts to link President Yudhoyono himself to the extra funds had failed, the inquiry’s focus soon shifted to Mulyani and Boediono.

Neither denied involvement, but both stressed that they had at all times acted in accordance with the law.8 As inance minister, Sri Mulyani had chaired the

Committee for Financial System Stability (Komite Stabilitas Sistem Keuangan), which in November 2008 made the decision to bail out Bank Century when the bank’s capital adequacy ratio fell well below zero. Boediono, too, was involved in the process, having then been governor of the central bank, which is responsi-ble for bank supervision. When the parliamentary inquiry committee questioned them about their roles, Mulyani and Boediono defended their actions by arguing

that, under the circumstances of the global inancial crisis, closing the bank, rather

than injecting new capital so as to bail out its depositors, would have had disas-trous consequences for the banking sector.

Inquiry committee members were unmoved though. After a lengthy and very public series of parliamentary hearings, broadcast live on a Bakrie-owned

tele-vision channel, the legislators declared the bail-out lawed and marred by cor -ruption and other irregularities. Although no evidence was presented to back up the corruption claims, a plenary session of the parliament on 3 March 2010, which according to media observers ‘ranged from boring to farcical’ (Rachman,

Hutapea and Saraswati 2010), endorsed the committee’s indings by concluding that the Bank Century case was an ‘abuse of power by oficials from the mon

-etary and iscal authorities [...] that could qualify as a suspected act of corruption’

(Wedhaswary 2010a). In addition, the parliament recommended that Mulyani and Boediono be subjected to further investigation by law enforcement institu-tions, including the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberan-tasan Korupsi, KPK).9 Soon afterwards, legislators began to collect signatures

for the initiation of impeachment procedures against Boediono. This, however,

6 PDI–P: Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan (Indonesian Democratic Party of Strug-gle); Hanura: Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat (People’s Conscience Party); Gerindra: Partai Gerakan Rakyat Indonesia Raya (Greater Indonesia Movement Party).

7 For details on the Lapindo mudlow disaster, see Thee and Negara (2010), in this issue. 8 By contrast, the former owner of the bank, Robert Tantular, was convicted in September 2009 of corruption and various banking crimes that contributed to its failure (LaMoshi 2010). His initial four-year prison sentence was later extended to nine years by the Su-preme Court.

9 This recommendation was somewhat ironic, not only because most political observers regard Sri Mulyani as incorruptible, but also because the DPR had previously attempted to weaken the KPK on a number of occasions, for example, by delaying budget approvals and by watering down the wording of the 2009 Anti-corruption Court Law.

was merely a symbolic act without any real prospect of success, since Indonesia’s impeachment requirements are now fairly restrictive.10

Unsurprisingly, given the failure of the parliamentary inquiry to present any

evidence of corruption, the impeachment efforts soon izzled out, as did the crimi -nal investigations by the KPK. But the parliamentary inquiry committee did suc-ceed in wearing Sri Mulyani down, and after months of relentless criticism she eventually resigned on 5 May 2010 to take up a position as a managing director at the World Bank. The exact circumstances of Mulyani’s resignation remain some-what unclear. Some observers speculated that she had simply had enough of the constant criticism and interrogation, and therefore gladly accepted the offer from

the World Bank. Others believed that she was, in effect, ired from the cabinet – sacriiced, as Emmerson (2010) put it, ‘for the sake of a restoration of political com -ity between SBY and his opponents’. A third interpretation was that she was in fact unwilling to resign, but that she miscalculated the support she could expect from President Yudhoyono. According to this view, Mulyani attempted to use the World Bank offer to pressure Yudhoyono into backing her publicly against Bakrie and the parliamentary inquiry. Instead of declaring his unconditional support for her, the president decided that it was in his best interests to encourage his minister to accept the offer, and thereby put an end to the Bank Century saga (Cochrane 2010). Indeed, once Mulyani had announced her resignation, the inquiry swiftly lost momentum. In particular, Golkar’s interest in it ended as quickly as it had begun.

Within hours of the inance minister’s announcement, leading Golkar politician

Priyo Budi Santoso declared that ‘if Sri Mulyani is out of the political and legal loop after she resigns, Golkar will respect [this]. Even if the case is closed, Golkar will have no problem with it’ (Jakarta Globe, 6/5/2010). And so it happened. Even though law enforcement institutions launched a formal criminal investigation as requested by the parliamentary inquiry, no evidence of criminal activity was found, and the case quickly disappeared from view.

The Bank Century saga exempliied in three respects the way Indonesian poli -tics evolved throughout 2010. First, it epitomised the tendency of parliament to dedicate enormous attention to issues beyond its normal mandate, while neglect-ing its regular duties of legislation. Second, it demonstrated that stable coali-tions will remain elusive in Indonesia as long as parties do not invest in internal reforms that could see them develop better organisational infrastructure, stronger programmatic identities and more professional recruitment policies. Third, it

conirmed Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s reputation as a cautious and indecisive

leader who tends to shy away from confrontation unless his own personal inter-ests are affected,11 and whose commitment to reform seems lukewarm at best.

10 According to Law 27/2009 on Legislative Bodies, parliament can only invoke its right to express an opinion that would pave the way for an impeachment process if it has the support of three-quarters of legislators at a plenary session. The president’s PD currently controls 26% of the seats in the DPR.

11 Yudhoyono did, for example, act more decisively when he ensured his enduring inlu-ence in PD by not only maintaining his position as chair of the Advisory Council (De-wan Pembina), but also, and more importantly, becoming chair of the newly created High Council (Majelis Tinggi), which was given authority to make key decisions such as the nomination of the party’s presidential candidate in 2014. SBY also demonstrated strength

In the following paragraphs I will analyse these three patterns of Indonesian poli-tics in more detail, using a number of key events throughout the year to illustrate how deeply ingrained they are.

THE DAWN OF A NEW ERA?

COALITION POLITICS AND PARLIAMENTARY PERFORMANCE

Just two days after Sri Mulyani’s resignation, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono sum-moned the members of his coalition to discuss ways to enhance the coherence of the cabinet. The result of the meeting was the establishment of a ‘joint secretariat’, whose task it would be to improve communication among the six coalition par-ties. In an ambitious statement, PD stalwart Anas Urbaningrum (later to become party chair) announced that the secretariat represented ‘the dawn of a new era of an organized coalition’ (Sihaloho 2010).

The man to guide the coalition into this new era as chair of the secretariat was Golkar Party leader Aburizal Bakrie – the very person who had orchestrated the attack on the senior economic minister in the coalition and who is widely regarded as a key obstacle to democratic reform in Indonesia. For some observers, Bakrie’s new position meant that Golkar had not only won the battle against Mulyani but

was also winning the wider struggle for power and inluence in the cabinet. Even

though neither the function of the secretariat nor the role of its chair was

particu-larly well deined, the Golkar leader was likened in some commentaries to a kind

of ‘prime minister’, who was effectively taking over the government.12

While it may be too early for a conclusive judgment, it seems clear that such rhetoric was very much misplaced. A key part of the problem is that parties in Indonesia often speak with several voices, since members of parliament tend to pursue very different interests from their party colleagues in cabinet. As Sherlock (2010: 174) has observed, ‘the behaviour of […] parties – in this and previous parliaments – suggests that they will feel little reluctance to criticise the actions of the government, even though they may be part of the administration themselves’. The formation of the joint secretariat was supposedly intended to deal with this problem and provide for more coherence among party lines put forward in parlia-ment and cabinet. So far, however, there is only limited evidence that the patterns of executive–legislature relations are changing. Nor is there much indication of a heightened sense of solidarity among the coalition parties within parliament.

Indeed, merely a month after the formation of the secretariat, the coalition parties and their parliamentary caucuses had again begun to speak with many voices, arguing either with the government or with each other over a controversial

during recent reshufles in the military when he promoted a number of generals who had served him in staff positions during his active time in the armed forces. Both moves helped the president to strengthen his grip over crucial bases of institutional support. However, they were hardly examples of leadership for the public good. (Thanks to Marcus Mietzner for his comments on these issues during the discussion of this paper at the Indonesia Up-date conference.)

12 See, for example, comments by Burhanuddin Muhtadi, a political analyst at the Indo-nesian Survey Institute, or Ari Dwipayana from Gadjah Mada University (Siahaan 2010; Unjianto 2010).

pork-barrel fund proposed by the Golkar Party. Shortly afterwards, disagreements surfaced again over the appropriate attitude towards Malaysia in the now almost ritualistic annual tensions with Indonesia’s northern neighbour. In both cases individual coalition parties and at times even individual members of coalition parties pursued their own agendas and did not shy away from publicly contra-dicting or criticising each other.

The irst public spat following the formation of the joint secretariat erupted in

early June over a proposal by the Golkar Party to give all DPR members Rp 15 bil-lion ($1.6 milbil-lion) in development funds for their constituencies (so-called ‘dana aspirasi’ or ‘aspiration funds’). Reminiscent of Philippine-style pork-barrel politics, the proposal drew immediate and widespread public criticism, not only because of its potential for corruption and vote-buying, but also because it violated exist-ing legislation and was seen as an attempt by legislators to interfere in the gov-ernment’s budget allocation (Transparency International Indonesia 2010).13 To

Golkar’s surprise, coalition partners PD, PKS and PAN soon joined the chorus of

criticism, and the new inance minister, Agus Martowardojo, also made it clear that

he would not support the plan. Taken aback, some Golkar politicians complained that they had been betrayed by the other parties, claiming that during talks in the joint secretariat all parties had endorsed the idea (Wedhaswary 2010b). Deputy chair Yamin Tawari even threatened that Golkar would leave the joint secretariat, forcing Aburizal Bakrie to intervene and dismiss Tawari’s statement as a personal opinion. President Yudhoyono, meanwhile, reacted rather late and seemed per-sonally offended by the statement. More than a week afterwards, he expressed his displeasure by declaring somewhat patronisingly that it was immature (kurang matang) for coalition members to issue such threats (Widhi K. 2010).

The pork-barrel proposal had barely disappeared from public discussion when law makers from the coalition parties became embroiled in another pub-lic disagreement. Once again it was Golkar that strayed from the coalition line, this time questioning the appropriateness of the government’s handling of the

latest border dispute with Malaysia. On 13 August 2010, three oficials from the Indonesian Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries were detained briely by Malaysian marine police in response to the arrest of seven Malaysian ishers by

Indonesian authorities in disputed waters off the coast of the Riau Archipelago province. After four days both sides released their detainees, but the incident had, as on previous such occasions, stirred up nationalist emotions in both coun-tries, and over the following days the Yudhoyono government was repeatedly accused of having caved in to Malaysia.

PDI–P legislators were particularly outspoken in their criticism, but Golkar, too, sensed an opportunity to score political points by fanning populist sentiment. As fringe nationalist groups organised raucous anti-Malaysia protests in Jakarta

13 According to Transparency International Indonesia (2010), the proposal violated no less than six laws: Law 17/2003 on State Finance; Law 1/2004 on the State Treasury; Law 32/2004 on Regional Government; State Audit Law 15/2004; Law 33/2004 on the Financial Balance between the Centre and the Regions; and Law 27/2009 on the People’s Consulta-People’s Consulta-tive Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat), the DPR, the Regional RepresentaConsulta-tive Council (Dewan Perwakilan Daerah) and the Regional People’s Representative Councils (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah).

and other big cities, several Golkar legislators expressed their support for the par-liament to invoke its right to call in the president for questioning (interpelasi, inter-pellation). On 30 August, party chair Aburizal Bakrie announced that he would

seek clariication from the government about the incident. The following day,

Agus Gumiwang Kartasasmita of Golkar’s parliamentary faction told the press that all but one of Golkar’s 107 DPR members had agreed to call the government in for questioning. Other coalition partners, however, refused to toe Golkar’s line. Left with no support outside his own party, Bakrie eventually changed his stance, signalling that a speech by President Yudhoyono on the issue had convinced him

that the government was suficiently determined to defend Indonesia’s interests

(Widjaya and Adam 2010).

It seems unlikely though that the president’s speech would have had such an effect. Indeed, the media quickly speculated that Golkar’s change of heart was

related to an impending cabinet reshufle. This suggestion could be interpreted

in two ways. On the one hand, it could mean that Golkar was rewarded for

with-drawing its threat of an interpellation with the prospect of greater inluence in a soon to be reshufled cabinet. Implicit in this interpretation is the ‘prime minister’

logic and the assumption that Aburizal Bakrie wields enormous leverage over Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. Alternatively, the suggestion could mean the oppo-site, namely that the president threatened to axe Golkar members from cabinet unless the party withdrew its support for the interpellation. Only if and when the

cabinet is indeed reshufled will we know whether either of these interpretations

holds true. There is, however, a distinct third possibility. It is in fact quite likely that Golkar’s decision to back down was not at all related to the possible cabinet

reshufle, but rather to the party’s failure to mobilise more support for its initia -tive. After the public relations disaster of the pork-barrel proposal, Bakrie may have felt that insistence on the interpellation would have left him and his party exposed to the very real possibility of being singled out as the only coalition mem-ber constantly to undermine the coherence of the cabinet. Arguably, for Bakrie, as leader of a joint secretariat intended to secure coalition solidarity, the risk of being stigmatised as the only spoiler was too high.

Regardless of the actual motivation for Golkar’s manoeuvres, the Malaysia row was yet another reminder of how easily Indonesia’s parliament is drawn into

highly unproductive debates. Signiicantly, a consequence of this by now very

familiar bickering between parliament and cabinet and between ostensibly allied parliamentary factions over issues of questionable importance has been that the DPR has spent very little time on legislation – supposedly one of its core

func-tions. In the irst 11 months of its term, the new DPR had passed only six laws.

Media reports often linked the poor legislation record to low attendance in

ple-nary sessions (Syofyan 2010), and legislators tried to delect public criticism by

discussing options for improving attendance in plenary sessions. For months,

suggestions such as public naming and shaming, ingerprint scanners and inan -cial penalties were publicly debated, while DPR members pointed to an internal working group set up to deal with the attendance question. Empty seats, how-ever, are not the main problem in the parliament. Key decisions about legislation are being made not in plenary sessions, but rather in the committees away from public view (Sherlock 2010). Therefore, the DPR’s poor legislation record could be tackled much more effectively by an overhaul of the opaque decision-making

processes than by forcing legislators to attend plenary sessions. More generally, what is needed is better selection of candidates and training of legislators, but for that to occur the political parties would need to get on board, and so far they have shown little inclination to invest in such measures.

SUCCESSION POLITICS WITHIN POLITICAL PARTIES

The poor performance of parliament and the failure of the joint secretariat to engender coalition unity should hardly cause surprise. For most of the last 10 years, legislative output has been low, and the parties have time and again dem-onstrated that they are incapable of forming meaningful coalitions. In the absence of genuine political values and ideational commitments, it has always been the pursuit of short-term interests and the need to safeguard access to power that dictated behavioural patterns among the political parties (Tomsa 2008). While this

has often led to supericial alliances, it has never resulted in genuine and endur -ing coalitions.

Of course, the lack of visionary ideas is just one of many problems the parties face. Other frequently mentioned shortcomings include poorly developed organi-sational infrastructure, neglect of parliamentary obligations, and susceptibility to

corruption and illicit fundraising (Mietzner 2007, 2008; Tomsa 2008; Ufen 2008).

That these issues are not just of concern for academic debates but can have direct consequences for the parties’ electoral prospects – and thus, by implication, for their long-term survival – became clear in 2009, when all but one of the six core parties represented in all post-1998 parliaments lost votes (Tomsa 2010a: 146).

Even those parties that did gain votes largely failed to fulil expectations. PKS, for example, had hoped to double its 2004 result, but gained less than 1%, while

the only two new parties that succeeded in winning seats in parliament (Gerindra and Hanura) barely cleared the parliamentary threshold. All in all, PD was

argu-ably the only party that could feel satisied with its result.

Over the last year, most parties had a golden opportunity to demonstrate publicly that they had heard the voters’ message. Golkar, Hanura, PAN, PDI–P and PKS, as well as the successful PD, all organised national party congresses between late 2009 and mid-2010. Given the disappointing election results of most of these parties, one might have expected that the congresses would become sites for tense leadership battles and starting points for some serious introspection or ‘soul-searching’, as Mietzner (2009a: 9) suggested with regard to Golkar. In most cases, however, this was not how the congresses unfolded. To begin with, three parties (PAN, Hanura and PDI–P) elected their leaders by acclamation rather than by vote, thereby stymieing any incipient debate about leadership and a change of direction. While PAN installed party veteran Hatta Rajasa at the helm, Hanura and PDI–P both re-appointed their incumbent chairs, despite poor party election results and the fact that their candidates, Wiranto and Megawati Soekarnoputri, had both been defeated in two successive presidential elections.14

The Golkar and PD congresses, on the other hand, did turn into hotly contested political battlegrounds after the two incumbent chairs, Jusuf Kalla (Golkar) and

14 To be precise, Wiranto ran only as vice-presidential candidate in 2009; for more details on the PDI–P congress see Aspinall (2010c).

Hadi Utomo (PD), gave early indications that they intended to resign. Given their leading positions in the current party system, both Golkar and PD are commonly regarded as attractive organisational vehicles for presidential hopefuls in 2014,

so it was hardly surprising that the two leadership contests attracted high-proile

candidates. By the time the congresses were held, any interest in programmatic discussions was clearly eclipsed by the high-stakes leadership contests.15 Yet,

despite their similarities in focus, the two congresses were markedly different in their results. In Golkar, the victory of 63-year-old Aburizal Bakrie represented a change of personnel, but otherwise signalled broad continuity. Bakrie, like his predecessors, Jusuf Kalla and Akbar Tandjung, is a product of the New Order, and

he secured his victory primarily because of his immense inancial clout and the

promise of access to government resources. In PD, on the other hand, the election of 41-year-old Anas Urbaningrum represented not only generational change but also a message that spending big and proximity to the president are not every-thing. Barrett (2010) called it ‘a victory for democracy’.

In contrast to all the other Indonesian parties, PKS did not organise its congress to elect its new leadership team. Instead, the congress, which was held in one of Jakarta’s most luxurious hotels, was merely a celebratory forum to inaugurate the members of the new leadership board and to disseminate information about the

party’s future direction. Signiicantly, all key decisions about personnel and policy

directions were made before rather than at the congress (Fealy 2010). As early as February 2010, eligible party cadres had elected the members of the party’s high-est decision-making body, the Religious Advisory Council (Majelis Syuro). The secretive council, whose members, activities and decision-making procedures are largely unknown to the public, then appointed the central leadership board and instructed it to continue with implementation of the party’s controversial mod-eration process, which aims to transform it from a puritanical Islamist party to a more open and pluralistic mainstream party (Shihab and Nugroho 2008). To what extent this decision enjoys the support of the grassroots could not be gauged at the congress, since there were no open forums for discussion. Anecdotal evidence seems to suggest, however, that there is at least some discontent with the way the party bosses are handling the moderation process.16 Furthermore, the stagnant

election result of 2009, and critical analyses by some political observers (Fealy 2010), point to ongoing credibility problems for the party, indicating that PKS will need to do more than make grand gestures such as holding its national congress in a Western luxury hotel.

All in all then, the various party congresses held over the last 12 months dis-played a clear trend towards continuity rather than change. Most parties have shied away from initiating efforts to build better organisational infrastructure or

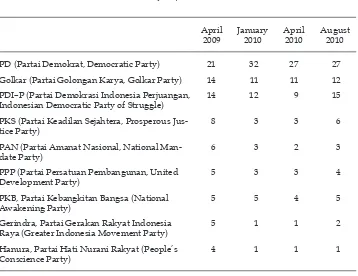

develop sharper ideological proiles. Voters who just last year expressed their dis -satisfaction with the parties at the ballot box are unlikely to be impressed with this failure to change. Indeed, opinion polls published in 2010 indicated that support for most parties was either stagnating or declining further (LSI 2010). In April

15 According to Barrett (2010), a session to discuss the ideological future of PD at the par-ty’s congress in Bandung attracted very little interest.

16 In particular, the apparent decline in piety and modesty among top cadres has raised some serious concerns at grassroots level (Fealy 2009).

2010, one year after the last legislative election, all parties except PD recorded support levels below their 2009 vote. Four months later, in August 2010, support

for PDI–P had risen six percentage points, to a igure slightly higher than its April 2009 election result, but PD was still the only party with a signiicantly enhanced

support base. The results of successive surveys by the Indonesian Survey Institute (Lembaga Survei Indonesia, LSI) are presented in table 1.

Although the survey igures show a negative trend for most core parties,17 they

caution against exaggerating the importance of the party congresses. There is, for example, no evidence of a causal connection between the events at the congresses and the poor survey results for most parties. On the contrary, despite extensive media coverage, party congresses appear to have had a negligible impact (if any at all) on how Indonesians perceive their political parties. This indifference, how-ever, carries an important message for the parties. At a time when their support is declining, parties could have used their congresses to send a clear message that they are willing to change. Since none seems to have done so, the electorate remains as disconnected as ever from the political elite.

17 Many respondents in the 2010 surveys refused to endorse any party, however, and ticked the ‘I don’t know’ box. There is therefore scope for parties to pick up additional sup-port from these undecided voters at the next election.

TABLE 1 Support for Political Parties (% of respondents)

PD (Partai Demokrat, Democratic Party) 21 32 27 27

Golkar (Partai Golongan Karya, Golkar Party) 14 11 11 12

PDI–P (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan,

Hanura, Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat (People’s Conscience Party)

4 1 1 1

Source: LSI (2010).

THE PRESIDENT AS ONLOOKER

Given the less than impressive performance of parties and parliament throughout

the year, the president might have been expected to reap some beneits. Indeed,

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono remains remarkably popular, with the latest

availa-ble survey, in August 2010, giving him an approval rating of 66% (LSI 2010). While this is signiicantly below the lofty 85% he enjoyed at the time of his re-election in July 2009, the recent igure mirrors his support rate for much of his irst term.

And yet there is a growing feeling among many Indonesians that the president is losing some of his political appeal. Distinctive features that were already

char-acteristic of his irst term, such as his indecisiveness, his tendency to wafle and

his extreme sensitivity to criticism, have received more intense media scrutiny in recent months. And while in some cases public condemnation of the president’s actions (or lack thereof) has been misguided,18 in other instances Yudhoyono’s

overly cautious, hands-off approach has been highly problematic for Indonesia’s democratic future. Three examples illustrate why.

First, during the Bank Century saga the president’s failure to stand up to the critics in parliament and vigorously defend his minister and vice president against spurious charges of wrong-doing weakened efforts to combat corruption

and damaged Indonesia’s international reputation (Allard 2010). During his irst term, Yudhoyono had made the ight against corruption one of the corner-stones

of his administration. Western commentators might sometimes have exaggerated the extent and the impact of these efforts, but there can be little doubt that some

gains were achieved and that Yudhoyono beneited from the bold investigations

of the KPK. However, when in late 2009 reactionary forces in the police and par-liament began to undermine the authority of the commission, the president stood idly by and did little to defend the anti-corruption forces.

In many ways, the Bank Century affair was a direct continuation of this pattern. From the beginning it seemed clear that the allegations against Sri Mulyani and Boediono were baseless (Patunru and Von Luebke 2010). Yet the crisis dragged on for months, with Yudhoyono once again watching passively from the palace. The

eventual departure of Mulyani was a major setback for the ight against graft, but

there were wider implications, too. Perhaps most importantly, Golkar’s relent-less attacks on arguably the most highly regarded ministers in Yudhoyono’s

cabi-net laid bare the president’s lawed judgment in having appointed yet another

rainbow cabinet in the belief that accommodating so many parties would ensure

smooth governing. When faced with the irst crisis after his re-election, Yudho -yono had neither the strength nor the determination to confront his opponents, and instead risked months of political paralysis in the faint hope that a solution would come his way. In the end, this ‘solution’ came in the form of Mulyani’s resignation but, as outlined above, her departure and the subsequent formation of the joint secretariat had, contrary to Yudhoyono’s expectations, relatively little

18 During the diplomatic spat with Malaysia in August, for example, Yudhoyono was ac-cused of being too soft on Indonesia’s neighbour in a speech from military headquarters in Cilangkap, East Jakarta (Simanjuntak 2010). In this case, the president was right to choose his words carefully and seek a quiet diplomatic solution, rather than further stir nationalist emotions on both sides.

impact on the pattern of president–parliament relations and the coherence of the ruling coalition.

Second, Yudhoyono has failed to demonstrate leadership in relation to the recent resurgence of religious intolerance and the concurrent debate about the appar-ent impunity of members of militant religious organisations such as the Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pembela Islam, FPI), the Forum of the Islamic Community (Forum Umat Islam, FUI) or the Indonesian Mujahidin Council (Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia, MMI). According to the Setara Institute for Democracy and Peace,

viola-tions of religious freedom rose in the irst half of 2010. Between January and July

2010, the institute documented 28 attacks on Christian churches alone, 10 more than in the whole of 2009 (Kompas, 27/7/2010). Apart from Christian communities, the Ahmadiyah sect was also repeatedly targeted by Islamic hard-liners, who regard its members as heretics. Most of the recorded incidents occurred in West Java and the Jabodetabek (Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, Bekasi) area. In other incidents of intolerance, FPI and FUI members attacked homosexuals in Surabaya (26 March), participants in a trans-gender workshop in Depok (4 May) and attendees at a meet-ing organised by PDI–P politicians in Banyuwangi (24 June). In the Banyuwangi case, the attackers alleged that their victims were communists.

Vigilantism in the name of religion is of course not a new phenomenon in Indonesia. FPI, for example, was founded as early as 1998, and has since devel-oped a notorious reputation for attacks on religious minorities and violent raids on places of alleged vice such as brothels, gambling halls and even art galleries (Wilson 2006). Over the years, the group has often acted in collusion with local politicians and elements within the police and military, so its members have long enjoyed virtual impunity.

This trend not only continued but was exacerbated in 2010. Perpetrators almost always escaped punishment, and in several cases police were reported to be pre-sent, but did ‘not lift a hand to prevent the hard-liners from using force’ (Arnaz 2010). In the overwhelming majority of cases, no arrests were made. Worse still, in several instances local politicians actively endorsed, or even ordered, the clo-sure of churches and of mosques run by the Ahmadiyah sect, sometimes appar-ently with a view to enhancing their Islamic credentials ahead of upcoming local elections. In late August, the Minister for Religious Affairs, Suryadharma Ali, weighed into the debate about Ahmadiyah, calling for the sect to be disbanded,

in clear conlict with the constitutional guarantee of freedom of religion. The min -ister thus directly contradicted his president, who just days before had used a function commemorating the Descent of the Koran to reiterate that everyone in Indonesia was free to practise his or her religion.

For President Yudhoyono, the comments by his minister, the general perception of an increase in religious intolerance and the ongoing impunity of groups like FPI should be highly embarrassing, and a matter for grave concern. Yudhoyono likes to highlight Indonesia’s success as a tolerant Islamic democracy at home and abroad, but apart from occasional appeals to uphold freedom of religion he has done little to stop the spread of violence. He has, for example, failed to take a tough stance on violent groups like FPI, and has refrained from holding ministers like Suryadharma Ali to account for statements that undermine religious free-dom. Moreover, he has refused to rescind two controversial ministerial decrees that have indirectly paved the way for the resurgent attacks in 2010.

First, a 2006 decree by the religious affairs and home affairs ministries on the

establishment of houses of worship has provided a feeble justiication for sev -eral church closures in West Java. From the start, the controversial decree was regarded as a potential tool for religious hard-liners seeking to prevent religious minorities from practising their faith. As Salim (2007: 119–22) observed, the

decree makes it dificult for minorities to build or maintain places of worship,

because a religious community needs to demonstrate support from local resi-dents and a so-called ‘Communication Forum for Religious Harmony’ (a local consultation body prone to siding with the interests of the majority rather than upholding religious freedom). Unfortunately, developments in 2010 have vin-dicated early criticism of the decree. Second, a 2008 inter-ministerial decree on the Ahmadiyah sect, introduced by the same two ministries and the attorney general, has, through its vague language, directly contributed to ongoing dis-crimination against the group. Analysing the ‘semi-ban’, Van Klinken (2008: 369) wrote that its provision of permission to congregate but not to disseminate, as

well as the subsequent call by ministerial oficials and the Indonesian Ulema

Council (Majelis Ulema Indonesia, MUI) for Muslims to monitor Ahmadiyah’s

compliance with these requirements, were ‘tantamount to oficial acceptance of

vigilante violence’. Two years later, Van Klinken’s words appear prophetic: vigi-lante violence and ‘blame the victim’ rhetoric have become all too familiar fea-tures of the debate about Ahmadiyah. Unsurprisingly, human rights groups have repeatedly called on President Yudhoyono to rescind the 2008 decree (Human Rights Watch 2010), but instead he has let his religious affairs minister promote the idea of an outright ban on the sect.

Developments in Papua provide a third example of presidential indecisiveness and weak leadership, and their direct consequences for the quality of Indonesia’s

democracy. Even though the government has provided substantial inancial aid

to the troubled province under the special autonomy framework, the underlying sources of local grievances remain largely unaddressed. In particular, the strong

presence of the military, the continuing growth and inluence of the migrant popu -lation, and rampant corruption and misappropriation of funds allocated through the special autonomy framework have caused increasing local discontent. More generally, Jakarta’s apparent indifference to conditions in Papua has long gener-ated broad resentment. In late 2009 this indifference came to the fore once again when the home affairs ministry rejected Decision (Surat Keputusan, SK) 14 by the Papuan People’s Council (Majelis Rakyat Papua, MRP) to ban non-indigenous

Papuans from running for ofice in local elections. The rejection triggered a series

of demonstrations in Papua that culminated in the symbolic return of a copy of the special autonomy law to Jakarta at a protest march in Jayapura on 18 June 2010 (ICG 2010: 8).

Few would dispute that special autonomy has not achieved the goals enunci-ated when it was introduced in 2001. By any comparative measure, Papua remains plagued by poor governance, widespread poverty, inadequate health care and low education standards (Chaplin and Reckinger 2010). Even President Yudho-yono recently acknowledged that progress in Papua and the neighbouring West Papua province was far from satisfactory. Implicit in this acknowledgment was an admission, though not openly expressed, that his administration had failed to prevent these problems from occurring. Jakarta elites have seen special autonomy

as a case of sending money without proper oversight of its use. At the same time, they have shown little or no interest in the political and cultural dimensions of autonomy.

In the most recent crisis, a delegation of Papuans took their concerns about the rejection of SK14 directly to Jakarta, but they failed in their attempts to meet the president or even the home affairs minister, Gamawan Fauzi. Following this

rebuff, tensions in Papua intensiied, and the process of radicalisation is now

increasingly palpable. In view of this ‘deepening impasse’, the International Cri-sis Group (ICG 2010) recently called on the president to take personal charge of the stalled autonomy process and to change the government’s approach from

the supericial provision of welfare assistance to a genuine engagement with the political nature of the conlict. According to the ICG report, three issues are in

particular need of attention: the expansion of the political dimensions of special

autonomy; afirmative action policies; and a response to Papuan concerns about

in-migration. So far, the only concession Yudhoyono has made is to promise an audit of the current state of special autonomy. While appreciated by Papuans as a

irst step (Somba 2010), this audit is unlikely to address the various socio-political

grievances, which are unrelated to the allocation of budget measures. Moreover, the promise gives little indication as to whether Yudhoyono is willing to take a more direct role in the search for a solution.

The three examples outlined here demonstrate that the strengthened popular mandate Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono received in the 2009 elections has done little

to change his leadership style. As in his irst term, he is in charge, yet he rarely leads.

He enjoys the representative part of the job, but usually shies away from making tough decisions. Remarkably, in the eyes of many Indonesians this approach to the presidency appears to be a virtue rather than a liability. Tough-talking alternatives like Prabowo Subianto or Wiranto failed miserably in their attempts to challenge Yudhoyono in 2009, and one year after the election the president remains by far the most popular politician in Indonesia (Indo Barometer 2010).

To explain Yudhoyono’s leadership style and its enduring appeal, it is necessary to consider the structural environment in which he came to power. Most notably,

he has beneited from the prevalence of a political culture incubated during the New Order that is heavily inluenced by an emphasis on compromise and coop -eration. While the Soeharto regime was of course often ruthless in its suppression of outspoken opposition groups, it also co-opted many of its critics by providing incentives for moderation and restraint (Aspinall 2005). Yudhoyono himself prac-tised these attributes extensively during his time in the army, especially in the late New Order years, when he became closely associated with qualities such as mod-eration and negotiation. After 1998, the protracted nature of Indonesia’s demo-cratic transition perpetuated this political culture, as became clear during the

short-lived presidencies of former semi-opposition igures Abdurrahman Wahid

and Megawati Soekarnoputri (Aspinall 2010d). By the time Yudhoyono rose to power in 2004, Jakarta’s elite still consisted largely of old-established politicians, bureaucrats and entrepreneurs who had long internalised this style of doing poli-tics. Thus it was unlikely from the start that the SBY presidency would mark a clear break from the past.

In fact, even though he was initially reluctant to enter politics (Mietzner 2009b: 236), Yudhoyono’s style of governing has in many ways been quite similar to that

of his predecessors, especially Megawati. Like Megawati, for example, Yudho-yono has always sought to build grand coalitions, appease competing factions within these coalitions and maintain at least a facade of harmony. Also like Mega-wati, he has remained slightly aloof from the day-to-day business of governing, delegating whenever possible to his subordinates. And like Megawati – and in fact like Soeharto before her – Yudhoyono has sought to present himself to the

nation as a parental igure who provides guidance beyond the vested interests of

‘normal’ elite politics.

That SBY became so successful with this leadership style can of course be attributed partly to the stable socio-economic and socio-political conditions

dur-ing his irst term. At the end of 2010, Indonesia’s basic political and economic

parameters remain intact, as economic growth continues and democratic rule is still widely accepted as the only legitimate means to distribute formal political

power. Yudhoyono certainly still beneits from this stability. But it may be argued

that two other factors also play an important role in explaining his continuing popularity. First, he has proven extremely skilful in creating and cultivating an image that, despite similarities with previous presidents, portrays him as being different from the rest of the political elite. Even though he has been a member of precisely this political (as opposed to military) establishment for a whole dec-ade now, his career path as a politician has been shaped by constant attempts to present himself as an outsider who is not part of the established elite, particularly the party elite. If in the early days as a minister Yudhoyono’s strategy was to assume the role of the misunderstood victim of ruthless power politics (Mietzner 2009b),19 during his presidency he switched to the role of benevolent father igure,

an image that came to the fore again most recently when he scolded his ministers for being slow to respond to critical issues (Kompas, 24/8/2010). Those comments of course ignored the fact that he too had often been slow to act, and that these were his ministers, for whose appointment and performance he was responsible. But as has become customary over the last six years, success stories and achieve-ments tend to be summarily claimed by the president, while government failures are always someone else’s fault.

The other factor that has helped Yudhoyono to reach and maintain his high levels of popularity is the institutional design of Indonesia’s post-Soeharto democracy. Arguably, the combination of a strong presidency and a fragmented multi-party system, so often criticised by political analysts, suits Yudhoyono per-fectly. Given the way he has situated himself among Jakarta’s party elites, it seems inconceivable that he could have won an indirect presidential election in the Peo-ple’s Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat, MPR) in the way Abdurrahman Wahid had done in 1999. But thanks to the introduction of direct presidential elections in 2004, he was able to exploit his carefully crafted image as the charismatic ‘outsider’ who came to power to end the domination of the tradi-tional party elites. At the same time, Yudhoyono very much needed these party elites in order to create an antagonistic opposite against which he could position himself. Indonesia’s electoral rules and the resultant fragmented party system,

which purportedly ‘forced’ him to accommodate some of these party igures in

19 Classic examples of this were his dismissal from the Wahid administration in June 2001 and his dramatically orchestrated resignation from the Megawati cabinet in February 2004.

his cabinet, were ideally suited to this strategy, since they helped reinforce the romanticised notion of an upright president surrounded by greedy and self-inter-ested parties.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

All in all, political developments during the irst year of SBY’s second term as

president give some cause for concern about the future of Indonesian democracy. In many ways, the Bank Century affair at the beginning of the year set the tone for things to come in 2010, signalling early on that the dominant patterns of

Indo-nesian politics, such as presidential caution, parliamentary ineficiency and weak

party institutionalisation, would remain largely unchanged. Over the course of the year, Indonesia repeatedly became bogged down in prolonged public debates over issues of questionable importance, while urgently needed reform initia-tives received little attention from either cabinet or parliament. As institutional inertia spread, conservative forces sought to capitalise on the growing sense of stagnation by trying to undermine or reverse some of the earlier achievements of the democratisation process. Bakrie’s successful campaign to oust reformist

inance minister Sri Mulyani, dubbed ‘political thuggery’ by respected journalist

Goenawan Mohamad (2010), was the most obvious example of this trend, but other cases not discussed in this article could also be mentioned in this context.20

In response to the growing anti-reformist trend among Jakarta’s elite, public

pressure on the president, parliament and the parties intensiied over the year,

as civil society groups and parts of the mass media took it upon themselves to

expose Indonesia’s various democratic deicits. In particular, fading oficial sup

-port for the ight against corruption, the government’s failure to stem the spread of

religious intolerance and the poor performance of parliament were often harshly criticised by outspoken journalists and non-government organisations. At times some of this criticism no doubt missed the mark (for example, the complaints about empty seats in the DPR’s plenary sessions), but in general the various cam-paigns were testament to an acute awareness among activists that without public pressure Indonesia may be heading in a potentially dangerous direction.21

Signiicantly, at least some of these campaigns did have an impact. Golkar’s

pork-barrel fund proposal, for example, was abandoned after a barrage of criti-cism and protests that included public demonstrations, critical media coverage and the establishment of a facebook site (‘Tolak dana aspirasi DPR’, ‘Reject the DPR’s aspiration fund’) that attracted nearly 8,000 members. Earlier in the year, public pressure had resulted in the re-instatement of two members of the KPK who had falsely been accused of soliciting bribes. Civil society thus provided a much-needed corrective to the uninspiring performance of Jakarta’s political

elite. But, sooner rather than later, civil society groups will need to ind commit -ted allies in powerful places if the stalled process of democratic deepening is to

20 Further instances of this phenomenon include the implementation of internet censor-Further instances of this phenomenon include the implementation of internet censor-ship in the name of curbing moral degradation, and calls for the abolition of direct local elections.

21 For a thorough discussion of the role played by non-government organisations in the ight against corruption in Indonesia, see Setiyono and McLeod (2010), in this issue.

regain momentum. With the next presidential election just four years away and

the current crop of potential contenders comprising such controversial igures as

Aburizal Bakrie, Prabowo Subianto and even Tommy Soeharto, the medium- to long-term prospects for Indonesian democracy do not appear particularly bright.

REFERENCES

Allard, Tom (2010) ‘Indonesia reels from corruption ighter’s departure for World Bank’, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 May.

Arnaz, Farouk (2010) ‘Lawmaker disgusted by police inaction on radicals’ raid on meet-ing’, Jakarta Globe, 23 July.

Aspinall, Edward (2005) Opposing Suharto: Compromise, Resistance, and Regime Change in Indonesia, Stanford University Press, Stanford CA.

Aspinall, Edward (2010a) ‘Indonesia: the irony of success’, Journal of Democracy 21 (2): 20–34.

Aspinall, Edward (2010b) ‘Indonesia in 2009: democratic triumphs and trials’, Southeast Asian Affairs 2010, ed. Daljit Singh, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 103–25.

Aspinall, Edward (2010c) ‘Princess of populism’, Inside Indonesia 99 (January–March), <http://www.insideindonesia.org/stories/princess-of-populism>.

Aspinall, Edward (2010d) ‘Semi-opponents in power: the Abdurrahman Wahid and Megawati Soekarnoputri presidencies’, in Soeharto’s New Order and Its Legacy: Essays in Honour of Harold Crouch, eds Edward Aspinall and Greg Fealy, Australian National University epress, Canberra: 119–34.

Baird, Mark and Wihardja, Maria Monica (2010) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 46 (2): 143–70.

Barrett, Luke (2010) ‘Transcending personality politics’, Inside Indonesia 101 (July– September), <http://www.insideindonesia.org/stories/transcending-personality-politics-24071335>.

Chaplin, Chris and Reckinger, Carole (2010) ‘Life is an everyday tragedy for Papuans’, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 August.

Cochrane, Joe (2010) ‘Politics in command: as she leaves, Sri Mulyani explains what hap-pened’, Jakarta Globe, 26 May.

Diamond, Larry (2009) ‘Is a ”rainbow coalition” a good way to govern?’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 45 (3): 337–40.

Emmerson, Donald K. (2010) ‘Exit Sri Mulyani: corruption and reform in Indonesia’, East Asia Forum, 9 May, accessed 6 September 2010 at <http://www.eastasiaforum. org/2010/05/09/exit-sri-mulyani-corruption-and-reform-in-indonesia/>.

Fealy, Greg (2009) ‘Indonesia’s Islamic parties in decline’, Inside Story, 11 May, accessed 11 September 2010 at <http://inside.org.au/indonesia%E2%80%99s-islamic-parties-in-decline/>.

Fealy, Greg (2010) ‘Front stage with the PKS’, Inside Indonesia 101 (July–September), <http://www.insideindonesia.org/stories/front-stage-with-the-pks-04091353>. Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Indonesia: end policies fueling violence against religious

minority’, Statement issued 2 August, accessed 14 September 2010 at <http://www. hrw.org/en/news/2010/08/02/indonesia-end-policies-fueling-violence-against-religious-minority>.

ICG (International Crisis Group) (2010) ‘Indonesia: the deepening impasse in Papua’, Asia Brieing No. 108, 3 August, ICG, Jakarta and Brussels.

Indo Barometer (2010) ‘Parliamentary threshold, amandemen UUD 1945, dan prospek poli-tik menjelang setahun SBY–Boediono [Parliamentary threshold, amendments to the 1945 Constitution and political prospects in the run-up to one year of SBY–Boediono]’,

Indo Barometer, Jakarta, accessed 3 October 2010 at <http://www.indobarometer. com/ib/index.php>.

LaMoshi, Gary (2010) ‘End in sight for Bank Century circus’, AsiaTimes Online, 11 March, <http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Southeast_Asia/LC11Ae02.html>.

LSI (Lembaga Survei Indonesia, Indonesian Survey Institute) (2010) ‘Akuntabilitas poli-tik: evaluasi publik atas pemerintahan SBY–Boediono [Political accountability: public evaluation of the SBY–Boediono government]’, LSI, Jakarta, accessed 7 October 2010 at <http://www.lsi.or.id/>.

McLeod, Ross H. (2010) Economic and political perspectives on the Bank Century case, Presentation to the Indonesia Study Group at the Australian National University, Can-berra, 19 May.

Mietzner, Marcus (2007) ‘Party inancing in post-Soeharto Indonesia: between state subsi-dies and political corruption’, Contemporary Southeast Asia 29 (2): 238–63.

Mietzner, Marcus (2008) ‘Soldiers, parties and bureaucrats: illicit fund-raising in contem-porary Indonesia’, South East Asia Research 16 (2): 225–54.

Mietzner, Marcus (2009a) ‘Indonesia’s 2009 elections: populism, dynasties and the consoli-dation of the party system’, Lowy Institute for International Policy, Sydney, accessed 6 September 2010 at <http://www.lowyinstitute.org/Publication.asp?pid=1039>. Mietzner, Marcus (2009b) Military Politics, Islam, and the State in Indonesia, Institute of

South-east Asian Studies, Singapore.

Mohamad, Goenawan (2010) ‘Mencoba berpisah dari Sri Mulyani [Trying to separate from Sri Mulyani]’, Tempo, 24 May.

Patunru, Arianto A. and Von Luebke, Christian (2010) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 46 (1): 7–31.

Rachman, Anita, Hutapea, Febriamy and Saraswati, Muninggar Sri (2010) ‘Bailout broke laws, says Indonesia’s divided house’, Jakarta Globe, 4 March.

Salim, Arskal (2007) ‘Muslim politics in Indonesia’s democratisation: the religious majority and the rights of minorities in the post-New Order era’, in Democracy and the Promise of Good Governance, eds Andrew MacIntyre and Ross H. McLeod, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 115–37.

Setiyono, Budi and McLeod, Ross H. (2010) ‘Civil society organisations’ contribution to the anti-corruption movement in Indonesia’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 46 (3): 347–70, in this issue.

Sherlock, Stephen (2009) ‘SBY’s consensus cabinet – lanjutkan?’, Bulletin of Indonesian Eco-nomic Studies 45 (3): 341–3.

Sherlock, Stephen (2010) ‘The parliament in Indonesia’s decade of democracy: people’s forum or chamber of cronies?’, in Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia: Elections, Insti-tutions and Society, eds Edward Aspinall and Marcus Mietzner, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 160–78.

Shihab, Najwa and Nugroho, Yanuar (2008) ‘The ties that bind: law, Islamisation and Indo-nesia’s Prosperous Justice Party (PKS)’, Australian Journal of Asian Law 10 (2): 233–67. Siahaan, Armando (2010) ‘Jury still out on Aburizal’s new role’, Jakarta Globe, 10 May. Sihaloho, Markus Junianto (2010) ‘Reshufle hands Bakrie leading coalition post’, Jakarta

Globe, 8 May.

Simanjuntak, Laurencius (2010) ‘PDIP nilai pidato SBY tunjukkan ketakutan terhadap Malay-sia [PDIP thinks SBY’s speech shows fear towards MalayMalay-sia]’, detikNews, 2 September. Somba, Nethy Dharma (2010) ‘Government urged to be thorough in auditing Papua funds’,

Jakarta Post, 3 August.

Sukma, Rizal (2009) ‘Indonesian politics in 2009: defective elections, resilient democracy’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 45 (3): 317–36.

Syofyan, Donny (2010) ‘Absenteeism breaks up trust from inside’, Jakarta Post, 9 August 2010.

Thee Kian Wie and Negara, Siwage Dharma (2010) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bul-letin of Indonesian Economic Studies 46 (3): 279–308, in this issue.

Tomsa, Dirk (2008) Party Politics and Democratization in Indonesia: Golkar in the Post-Suharto Era, Routledge, London and New York.

Tomsa, Dirk (2010a) ‘The Indonesian party system after the 2009 elections: towards stabil-ity?’, in Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia: Elections, Institutions and Society, eds Edward Aspinall and Marcus Mietzner, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 141–59.

Tomsa, Dirk (2010b) ‘A storm in a bank vault’, Inside Indonesia 100 (April–June), <http:// www.insideindonesia.org/edition-100/a-storm-in-a-bank-vault-01051299>.

Transparency International Indonesia (2010) Alokasi dana aspirasi akan menyuburkan politik uang [Allocation of aspiration fund will spawn money politics], Press release, 7 June, accessed 12 September 2010 at <http://www.ti.or.id/press/91/tahun/2010/ bulan/06/tanggal/07/id/4904/>.

Ufen, Andreas (2008) ‘From aliran to dealignment: political parties in post-Suharto Indo-nesia’, South East Asia Research 16 (1): 5–41.

Unjianto, Bambang (2010) ‘Ical perdana menteri koalisi [Ical prime minister of the coali-tion]’, Suara Merdeka Cybernews, 12 May.

Van Klinken, Gerry (2008) ‘Indonesian politics in 2008: the ambiguities of democratic change’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 44 (3): 365–81.

Van Zorge, James (2010) ‘(Not) all the president’s men: SBY’s insecurity should be uncon-stitutional’, Jakarta Globe, 14 May.

Wedhaswary, Inggried Dwi (2010a) ‘Inilah dua opsi yang dipertarungkan itu [These are the two options [legislators] are ighting over]’, Kompas.com, 3 March, accessed 29 Septem-ber 2010 at <http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2010/03/03/09382629/Inilah.Dua. Opsi.yang.Dipertarungkan.Itu>.

Wedhaswary, Inggried Dwi (2010b) ‘Golkar: Setgab setuju dana Rp 15 m [miliar: billion] [Golkar: Joint Secretariat agreed on Rp 15 billion fund]’, Kompas.com, 4 June, accessed 12 September 2010 at <http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2010/06/04/15433358/ Golkar:.Setgab.Setuju.Dana.Rp15.M>.

Widhi K., Nograhany (2010) ‘SBY: Kalau ada seperti itu, itu bukan Setgab [SBY: If some-thing like that happens {a threat to leave the Joint Secretariat}, this is not a Joint Secre-tariat’], detikNews, 18 June, accessed 5 October 2010 at <http://us.detiknews.com/read /2010/06/18/164130/1381484/10/sby-kalau-ada-seperti-itu-itu-bukan-setgab>. Widjaya, Ismoko and Adam, Mohammed (2010) ‘Golkar batal interpelasi soal Malaysia

[Golkar cancels interpellation over Malaysia issue]’, Vivanews, 2 September, accessed 13 September 2010 at <http://politik.vivanews.com/news/read/175078-golkar-batal-interpelasi-soal-malaysia>.

Wilson, Ian Douglas (2006) ‘Continuity and change: the changing contours of organized violence in post-New Order Indonesia’, Critical Asian Studies 38 (2): 265–97.