Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 22:23

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Gratitude in Graduate MBA Attitudes:

Re-Examining the Business Week Poll

Morris B. Holbrook

To cite this article: Morris B. Holbrook (2004) Gratitude in Graduate MBA Attitudes: Re-Examining the Business Week Poll, Journal of Education for Business, 80:1, 25-28, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.1.25-28

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.1.25-28

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 16

View related articles

he last 50 years surely will go down in the annals of business education as the era in which strategic thinking embraced the concept of cus-tomer orientation (Drucker, 1954; Levitt, 1960) and pushed this conven-tional wisdom into enterprises in all walks of life, including not only for-profit ventures but also such disparate areas as medicine, religion, politics, and, inevitably, education itself (Fulton, 1994; Keat, Whiteley, & Abercrombie, 1994). Education in the service of cus-tomer orientation has suggested the merits of offering students information that they find easy and fun to assimilate (“edutainment”), collecting feedback for the purpose of guiding teachers toward the creation of more popular course offerings (student evaluations), and designing programs intended to enhance the careers of graduates by fos-tering their success on the job market (vocationalism or, less politely, the “trade-school mentality”). Often, such academic compromises occur in ways that have prompted shocked outcries from those (beginning with Veblen, 1918) committed to the advancement of higher learning in America (Aronowitz, 2000; Bok, 2003; Crainer & Dearlove, 1999; Edmundson, 1997; Holbrook, 1998; Holbrook & Day, 1994; Read-ings, 1996; Rotfeld, 2001; Sacks, 1996; Shumar, 1997; Zimmerman, 2001).

Nowhere has the ethos of customer orientation been more insistent or more frequently criticized (“Ranking business schools . . .” 2002; Schatz, 1993) than in the periodic polls claiming to identify the “best schools” in general and the “top” business schools in particular. Consider, for example, the surveys com-piled and reported every couple of years by such publications as Forbes (Baden-hausen & Kump, 2003), U.S. News & World Report (USN&WR) (Morse & Flanigan, 2003), and, most conspicu-ously, Business Week (Merritt, 2002). These magazines differ somewhat in the aspects of business school (B-school)

excellence most strongly emphasized. Forbes focuses primarily on career-related considerations regarding post-MBA salaries and other compensation. USN&WR includes an assessment of academic excellence. Business Week (BW) touts a customer orientation based on the concerns of corporate recruiters and on evaluations by recent MBA graduates.

Because these rankings are read uni-versally, publicized vociferously, and regarded widely with an exaggerated degree of credulity, deans and other business-school administrators do what they can to achieve favorable showings in the various polls. The much-debated and often-discredited systems of stu-dent evaluations (Sproule, 2000) pro-vide just one example of the hoops through which accommodating school administrations willingly jump to cater to students’ whims and wishes. Thus, in many or even most B-schools, customer orientation and customer-relationship management—or just plain pandering to the students—has become a mantra rivaled only by that dedicated to maxi-mizing shareholder wealth.

Looking at the consequences of cus-tomer orientation from a somewhat dif-ferent angle, one might ask what rewards a school gains by bending over back-wards to cater to its student-customers’ desires. This question raises the issue of

Gratitude in Graduate MBA

Attitudes: Re-Examining

the

Business Week

Poll

MORRIS B. HOLBROOK Columbia University New York, New York

T

ABSTRACT. As the strategic com-mitment to customer orientation has penetrated all aspects of corporate life, including business education, various publications (e.g., Business Week) increasingly have been conducting polls that rank schools on criteria that include evaluations by their former students. These student evaluations reflect certain objective characteristics of the schools as well as a remaining positive or negative residual that may be attributed to gratitude or ingrati-tude. In this study, the author investi-gated how business schools would be ranked in such polls if graduates’ assessments reflected the schools’ objective characteristics free from the biases of gratitude or ingratitude. Results show that some schools’ rank-ings would drop precipitously, where-as others’ rankings would rise.

how much students appreciate having their career needs and vocational wants met at every turn. In short, it raises the issue of gratitude.

Holbrook (1993) proposed a measure of MBA gratitude, as reflected by the Business Week (BW) poll. Specifically, the poll collects data from corporate recruiters and from recent MBA gradu-ates and combines these into an overall ranking. BWalso reports scores for each school on a variety of other objective and quasi-objective measures. The approach proposed by Holbrook uses all available objective and quasi-objective data from sources other than the MBAs themselves to explain the graduate eval-uations and then treats the residuals or error terms as an index of student grati-tude. In other words, those graduates who like their schools better than any objective measures would display grate-fulness. Those who give ratings below the levels justified by available predic-tors show ingratitude. Operationally, this approach regresses results for the graduate poll on all available objective and quasi-objective predictors, com-putes residual error scores, and regards these residuals as indicators of gratitude (positive errors) or ingratitude (negative errors).

Holbrook (1993) estimated that the most ungrateful business school gradu-ates came from Wharton, Columbia, Michigan, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and the Univer-sity of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), in that order. We might won-der, first, what we would find if we reapplied his method to the results of the Business Week poll conducted a decade after the original study by Hol-brook and reported by Merritt (2002). Toward that end, in the present research I regressed the 2002 graduate-poll results for the top 30 business schools on 17 objective and quasi-objective variables provided by BW. These variables included the following predictors:

• Evaluations by corporate recruiters • An assessment of intellectual capital • Annual tuition

• Applicant acceptance rate

• Enrollments of female, international, and minority students

• Pre- and post-MBA pay

• Percentage of students with job offers at graduation

• Average work experience prior to the MBA

• Recruiter ratings of students on ethics, teamwork, and analytic skills

The analysis also included three mea-sures of MBA “worth” along the lines suggested by Hindo (2002):

• Percentage increase in compensa-tion = post-MBA pay/pre-MBA pay

• Return on investment = (post-MBA pay – pre-MBA pay)/tuition

• Years to payback = [(2 ×tuition) + (1.5 × pre-MBA pay)]/(post-MBA pay – pre-MBA pay)

In a stepwise regression of the graduate-poll results on these 17 objec-tive and quasi-objecobjec-tive variables, the only predictor that emerged as statisti-cally significant, explaining half the variance in student evaluations, was post-MBA pay (r = .70, r2 = .49, p <

.001). However, my aim in the present study was not just to find the significant predictors of graduate ratings. Rather, I sought to explain as much of the vari-ance in the graduate poll as possible so as to obtain a residual measure of (in)gratitude. Toward this end, forcing all 17 predictors into the equation pro-duced an overall explained variance of R2= .725. Though not statistically

sig-nificant (because of the few degrees of freedom remaining when using 17 vari-ables to predict the scores for 30 schools), this relationship used objec-tive and quasi-objecobjec-tive characteristics to explain close to three quarters of the variance in the graduate-poll results.

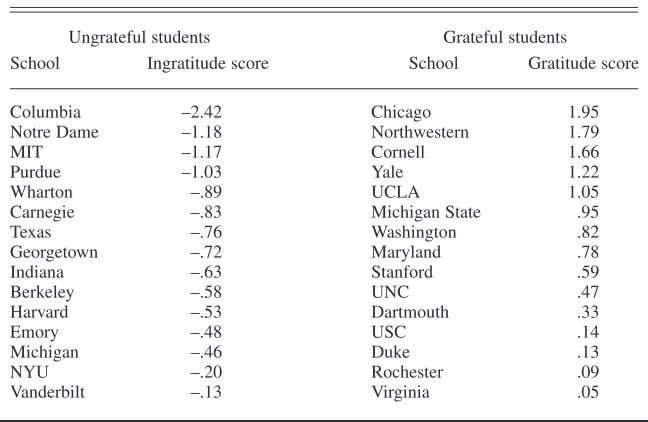

As already noted, the residual error terms in the predictions described above provided assessments of gratitude or ingratitude among the graduates of each school. For the 2002 BWdata, I show these residuals-based (in)gratitude scores in Table 1.

It appears that several schools with high levels of ingratitude happen to be located in large eastern metropolises: Columbia (New York), MIT (Boston), Wharton (Philadelphia), Carnegie (Pittsburgh), Georgetown (Washington), Harvard (Boston), and NYU (New York). We might surmise that there exists something of a tough, eastern big-city “attitude” that inspires the gradu-ates of these schools to show low levels of appreciation for their MBA experi-ences. Indeed, if we represent the schools on that list by a zero–one dummy variable and correlate this dummy variable with our measure of gratitude, the relationship is moderately strong and statistically significant (r = –.54,r2= .29,p< .005).

One hardly can fail to notice that, despite their efforts to pursue customer orientation in any and every possible

TABLE 1. Residuals-Based Ingratitude/Gratitude Scores for the 30 Schools in the 2002 Business WeekData

Ungrateful students Grateful students

School Ingratitude score School Gratitude score

Columbia –2.42 Chicago 1.95

Notre Dame –1.18 Northwestern 1.79

MIT –1.17 Cornell 1.66

Purdue –1.03 Yale 1.22

Wharton –.89 UCLA 1.05

Carnegie –.83 Michigan State .95

Texas –.76 Washington .82

Georgetown –.72 Maryland .78

Indiana –.63 Stanford .59

Berkeley –.58 UNC .47

Harvard –.53 Dartmouth .33

Emory –.48 USC .14

Michigan –.46 Duke .13

NYU –.20 Rochester .09

Vanderbilt –.13 Virginia .05

way, some schools such as Columbia suffer rather spectacularly from what appears to be an elevated level of stu-dent ingratitude. Therefore, one might wonder how this difficulty might affect a school’s standing in the overall Busi-ness Week rankings. To address this question, I began by deriving the weights needed to explain BW’s overall ranking by means of the three scores that the magazine uses to derive its global assessment—namely, the corpo-rate poll (recruiter assessments), the graduate poll (student evaluations), and intellectual capital (a measure based on faculty publications and other kinds of notoriety). Regressing standardized overall rank on standardized scores for these three predictors produced weight coefficients of .617 for the corporate poll, .375 for the graduate poll, and .148 for intellectual capital, with an overall R of .98 (R2 = .96,p< .001). In this case,

the weight for recruiter assessments was over one and a half times as large as that for student evaluations, despite BW’s claim to weight the two equally. An obscure passage from Merritt (2002) can serve to explain this imbalance: “Because there tend to be greater differ-ences among schools in the corporate survey, recruiter opinion can have a greater impact on the overall ranking” (p. 88).

I then applied those weights to the standardized scores for the corporate poll, the predicted graduate poll, and intellectual capital, with the predicted student evaluations (based on the 17 aforementioned objective and

quasi-objective variables) substituted for those actually given by the graduates surveyed. In other words, I removed the effects of student (in)gratitude to estimate what the overall scores would have been had the graduate poll reflected objectively mea-surable aspects of each school, free from grateful or ungrateful biases for or against one’s own alma mater.

According to this approach, the actual and expected overall B-school rankings showed a strong statistical correlation of r= .96 (r2= .92,p< .001; Spearman r=

.95). Nevertheless, some of the expected rankings of schools (based on predicted student evaluations with the effects of gratitude and ingratitude removed) dif-fered considerably from the actual rank-ings reported by BW(compiled in a way that allows gratitude and ingratitude to exert its biasing effect). In Table 2, I show the actual and expected rankings of the “best” business schools included in the top 10 by BWfor 2002.

I found that several schools (Harvard, Stanford, MIT, Michigan, Duke, and Dartmouth) did not change much in their rankings as the result of student gratitude or ingratitude. However, it appears that the top two schools benefit enormously from the gratitude shown by their graduates. Thus, Northwestern and Chicago would fall from 1st and 2nd places to 6th and 11th, respectively, if the biases resulting from student grat-itude were removed. Conversely, a cou-ple of schools suffer from what appears to be a bad attitude or lack of apprecia-tion evinced by their former students. Specifically, were it not for ingratitude,

5th-place Wharton would rank 2nd. And, if its graduates were unbiased by extreme ingratitude toward their alma mater, Columbia would climb from 7th to 1st place in the rankings.

One might reasonably ask what all this means in terms of marketing strategy to an administrator such as a dean faced with the responsibility of managing a school’s public image. Ironically, it appears that customer orientation does not suffice to produce high levels of stu-dent gratitude and thereby fails to ensure a favorable ranking in the BW poll. Rather, gratitude seems to stem from some sort of cultural biases that appear to differ from one locale to another. Conse-quently, to the extent that the BW rank-ings matter to a school’s fortunes (as they so obviously do in today’s customer-oriented and careerist climate), an aca-demic administration might be well-advised to adjust its admissions process in ways intended to attract and accept students predisposed toward appreciative and grateful responses.

Such a proposed strategy raises the question of how a school might find and select those candidates characterized by habitual tendencies toward appreciation and gratitude. One workable approach might be to include a question or set of questions on the admissions form to inquire about the excellence of the applicant’s prior educational and work experiences. Candidates who gave low scores to their former colleges or down-graded their previous jobs might be eliminated from further consideration on the grounds that they probably will do exactly the same thing to their grad-uate business schools when contacted by Business Weekat the end of their MBA programs. To paraphrase the old saying, the best predictor of future (in)gratitude may well be past (in)gratitude.

REFERENCES

Aronowitz, S. (2000). The knowledge factory: Dismantling the corporate university and creat-ing true higher learncreat-ing.Boston: Beacon Press. Badenhausen, K., & Kump, L. (2003, October 13). B-schools: The payback. Forbes, 172, 78–79.

Bok, D. (2003). Universities in the marketplace: The commercialization of higher education.

Princeton: Princeton University Press. Crainer, S., & Dearlove, D. (1999). Gravy

train-ing: Inside the business of business schools.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

TABLE 2. Actual and Expected Ranks of Schools Ranked in the Top 10 by the 2002 Business WeekPoll

School Actual rank Expected ranka

Northwestern 1 6

Chicago 2 11

Harvard 3 3

Stanford 4 5

Wharton 5 2

MIT 6 4

Columbia 7 1

Michigan 8 8

Duke 9 7

Dartmouth 10 9

aBased on expected rankings of 30 schools.

Drucker, P. F. (1954). The practice of manage-ment.New York: Harper and Row.

Edmundson, M. (1997, September). On the uses of a liberal education: I. As lite entertainment for bored college students. Harper’s, 295,39–49. Fulton, O. (1994). Consuming education. In R.

Keat, N. Whiteley, & N. Abercrombie (Eds.),

The authority of the consumer(pp. 223–239). London: Routledge.

Hindo, B. (2002, October 21). An MBA: Is it still worth it? Business Week,104–106.

Holbrook, M. B. (1993). Gratitudes and latitudes in M.B.A. attitudes: Customer orientation and the Business Weekpoll. Marketing Letters, 4,

267–278.

Holbrook, M. B. (1998). The dangers of education-al and cultureducation-al populism: Three vignettes on the problems of aesthetic insensitivity, the pitfalls of pandering, and the virtues of artistic integrity.

Journal of Consumer Affairs, 32,394–423. Holbrook, M. B., & Day, E. (1994). Reflections

on jazz and teaching: Benny and Gene, Woody

and We. European Journal of Marketing, 28(8/9), 133–144.

Keat, R., Whiteley, N., & Abercrombie, N. (Eds.) (1994). The authority of the consumer. London: Routledge.

Levitt, T. (1960, July/August). Marketing myopia.

Harvard Business Review, 37,45–56. Merritt, J. (2002, October 21). The best B-schools.

Business Week,84–100.

Morse, R. J., & Flanigan, S. M. (2003, April 14). How it happens: The methodology behind the

U.S. Newsgrad school rankings. U.S. News & World Report, 134,62–64.

Ranking business schools: The numbers game. (2002, October 12). The Economist, 365,65. Readings, B. (1996). The university in ruins.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Rotfeld, H. J. (2001). Adventures in misplaced

marketing.Westport, CT: Quorum Books. Sacks, P. (1996). Generation X goes to college: An

eye-opening account of teaching in postmodern America. Chicago: Open Court.

Schatz, M. (1993). What’s wrong with MBA rank-ing surveys? Management Research News, 16(7), 15–18.

Shumar, W. (1997). College for sale: A critique of the commodification of higher education. Lon-don: Falmer Press.

Sproule, R. (2000, November 2). Student evaluation of teaching: A methodological critique of con-ventional practices. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8. Retrieved from http://olam.ed.asu/ edu/epaa/v8n50.html

Veblen, T. (1918, 1957). The higher learning in America: A memorandum on the conduct of universities by business men. New York: Hill and Wang.

Zimmerman, J. L. (2001). Can American business schools survive? Working Paper No. FR 01-16, Bradley Policy Research Center, William E. Simon Graduate School of Business Administra-tion, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrm.com/abstract= 283112