Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Teaching Market Mechanisms and Human Capital

in Economics Courses: Examples From Jersey

Transactions in Professional Sports

Franklin G. Mixon , Sean P. Salter & Michael C. Withers

To cite this article: Franklin G. Mixon , Sean P. Salter & Michael C. Withers (2006) Teaching Market Mechanisms and Human Capital in Economics Courses: Examples From Jersey Transactions in Professional Sports, Journal of Education for Business, 82:1, 35-39, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.82.1.35-39

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.82.1.35-39

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 28

View related articles

ABSTRACT. As professional athletes

are traded from team to team, various

in-kind and monetary transactions for certain

jersey numbers are becoming more

com-mon. Given the size of some of the recent

payments, these stories have transitioned

from relative obscurity to mainstream

sports news. In this article, the authors

pro-vide two areas where these kinds of

interac-tions can enhance the learning experience

in undergraduate microeconomics or

under-graduate labor and sports economics. These

are (a) simple, illustrative ways of

dis-cussing the importance of markets (and

related concepts), and (b) an interesting

extension of G. S. Becker’s (1975) human

capital theory.

Key words: human capital investment,

mar-kets, teaching of economics

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

Teaching Market Mechanisms and

Human Capital in Economics Courses:

Examples From Jersey Transactions in

Professional Sports

FRANKLIN G. MIXON JR. MICHAEL C. WITHERS SEAN P. SALTER UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MISSISSIPPI TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA HATTIESBURG, MISSISSIPPI

“Superman’s not Superman when he doesn’t have his cape. I finally got my cape back, so I feel like Superman,” said Clinton Portis, Washington Redskins run-ning back, upon acquiring the #26 he wore at the University of Miami. ( Union-Tribune News Service, 2004, para. 5)

“We negotiated this thing for two weeks. I’m serious. . . . my family kept hounding me to get back my old number,” said Ter-rell Buckley, Miami Dolphins defensive back, upon acquiring the #27 he wore at Florida State University. (Salguero & Est-wick, 2003, para. 4)

ans and sports enthusiasts have always associated certain jersey numbers with their sports heroes. Some examples that quickly come to mind are professional hockey great Wayne Gretzky’s #99, National Bas-ketball Association (NBA) legend Michael Jordan’s #23, National Foot-ball League (NFL) superstar Joe Mon-tana’s #16, and Major League Baseball (MLB) All-Star Derek Jeter’s #2. The importance of sports jerseys and their accompanying numerical identifica-tion to fans is clearly identified by the size of the sports memorabilia market in the U.S. and worldwide. Sales of NBA jersey regalia alone climbed to $3 billion during the 2002–2003 sea-son, and sales were expected to top $3.6 billion during the 2003–2004 sea-son (Rovell, 2003). Upon being recent-ly traded to new teams, both Clinton

Portis and Terrell Buckley exhibited a strong desire to reacquire the jersey numbers they wore in college and ear-lier in their professional careers. The two paid from $7,000 to $45,000 to acquire the numbers 26 and 27 from previous owners.

At the very least, these types of trans-actions offer a unique and interesting example of the market mechanism for principles students. These transactions highlight the importance of concepts such as willingness to pay, allocation mechanisms, free markets, and others that are integral to principles of micro-economics courses. Beyond that, the motivation on the buyer’s motivation in these transactions may offer a useful story in principles of microeconomics or undergraduate courses in labor and sports economics.

In this article, we provide an avenue for pedagogically integrating the inter-esting stories behind jersey transactions in professional sports. To do so, we highlight two areas where these exam-ples can enhance the learning experi-ence in microeconomics: (a) as a sim-ple, illustrative way of discussing the importance of markets (and related con-cepts) in microeconomics principles, and (b) as an interesting extension of Gary Becker’s (1975) human capital theory in principles or intermediate microeconomics or in undergraduate labor and sports economics courses.

F

Jersey Transactions as the Market Mechanism

Many academic economists are, by now, familiar with the web–log (i.e., blog) known as Marginal Revolution. It is hosted by two economists, Tyler Cowen (George Mason University) and Alexander Tabarrok (The Independent Institute). Since its inception, the mar-ket mechanism discussion located there has grown in popularity. This blog cen-ters on novel uses of the market mecha-nism by ordinary citizens and business enterprises (worldwide) that are found either by the blog’s hosts or the blog’s regular participants. Interesting exam-ples in this discussion series (during 2004) are:

Example 1: The story of Yuolanda Taylor, a Michigan woman who earned about $70 selling rocks and stones to rioters in her southwest Michigan hometown. Police say Taylor toted rocks through a riot-wracked neighborhood, selling small ones for $1 and bigger ones for $5. Pros-ecutors say the rocks were thrown at police. (Cowen, 2004a, para. 1–2)

Example 2: The story of Breakupservice .com, the Internet-based company (found-ed in 2002) that offers custom-tailor(found-ed Dear John or Dear Jane letters that assist customers in terminating bad relation-ships. The company also offers an over-the-phone service. The price is $50. (Cowen, 2004b, para. 1–2)

Example 3: The story of Parkingticket .com, the first Internet company that helps drivers contest parking tickets online. If the ticket is dismissed, cus-tomers pay a fee ($25). No dismissal, no charge. (Cowen, 2004c, para. 1–4)

These stories are unique and offer interesting examples of the responsive-ness of the market forces of supply and demand. As with these stories, the idea that a professional athlete would exhib-it such a strong preference for a certain jersey number is also intriguing.

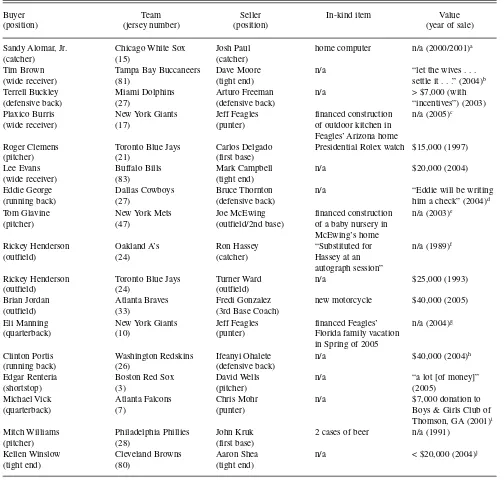

We conducted an Internet search that revealed a number of examples of this type of market activity in the NFL and in MLB. These are listed in Table 1. In most cases, the resulting price reveals a strong willingness to pay on the part of the buyer. For instance, MLB great Rickey Henderson reportedly paid Turner Ward $25,000 for #24 with the Toronto Blue Jays (Jones, 2004, para. 5). NFL wide receiver Lee Evans of the

Buffalo Bills paid Mark Campbell $20,000 for the purchase of jersey #83. NFL running back Clinton Portis ulti-mately paid Ifeanyi Ohalete $38,000 for jersey #26 with the Washington Red-skins (see Table 1; Pasquarelli, 2005, para. 2). Last, and on the lower end, NFL defensive back Terrell Buckley paid about $7,000 (plus performance incentives) to Arturo Freeman for #27 with the Miami Dolphins (Sanguero & Estwick, 2003, para. 1).

While these monetary figures are remarkable, some of the in-kind trades are just as interesting. For instance, pitching legend Roger Clemons pur-chased a Presidential Rolex watch val-ued at $15,000 for Carlos Delgado in exchange for jersey #21 with the Toron-to Blue Jays (Lowitt, 2001, para. 5). NFL rookie Eli Manning agreed to pay for the Florida vacation (in the Spring of 2005) of Jeff Feagles and his family in exchange for jersey #10 with the New York Giants. Such a gift could easily be valued at $10,000 or more (Eisen, 2005, para. 8-9). Finally, as Table 1 indicates, Brian Jordan bought a motorcycle val-ued at $40,000 for Fredi Gonzalez in exchange for jersey #33 with the Atlanta Braves (Jenkins, 2005, para. 11). The Jordan-Gonzalez trade is unique in that it involved a player (Jordan) and an assistant coach (Gonzalez). On a more humorous note, John Kruk sold jersey #28 with the Philadelphia Phillies to Mitch Williams for two cases of beer, a story Kruk is fond of recounting on tele-vision talk shows (Lowitt, para. 7–8).

These stories make good examples for teaching principles of economics students. Most students find that these negotiations and resulting prices are striking. These stories elicit questions such as: Who owns the property rights to these jersey numbers—the players that hold them or the team’s owners? Couldn’t the team’s owners simply auc-tion the numbers off to the highest bid-ders during the preseason and perhaps donate the receipts to charity (or retain them)? These questions bring to light several issues discussed in Boyes and Happel’s (1989) now well-known story about office space allocations in the College of Business at Arizona State University (ASU) where the university built a new building, and the economics

departments’ faculty had an auction to allocate professors’ office space in the new building. The Boyes and Happel (1996) story also addresses property rights issues regarding the office space auction by the economics department at ASU, and how the funds generated from the auction and subsequent trading in office space were to be used. Students commonly find the Boyes-Happel account of the office space auction by economists at ASU intriguing. The foot-ball jersey illustration often elicits simi-lar interest.

Jersey Transactions as Human Capital Investments

Following the work of Gary Becker (1975), “activities that influence future monetary and psychic income by increasing the resources in people” are now known as “investments in human capital” (p. 9). The phrase human capi-tal investment includes schooling, on-the-job training, medical care, migra-tion, and searching for information about prices and incomes because all of these investments improve skills, knowledge, or health, and thereby raise money or psychic incomes (Becker). Becker has also incorporated new types of human capital stocks into his earlier framework. These are personal and social capital—capital that directly influences consumption and utilities (Becker, 1996, pp. 4–5). An example of the former is imagination capital, or personal capital that helps individuals better appreciate the future or future utilities (Becker, p. 11; Becker & Mulli-gan, 1997).

The epigraph from Clinton Portis at the beginning of this article hints at another potential form of human (per-sonal) capital investment that we have not encountered in Becker (1975, 1996) or subsequent academic literature. It is possible that not having a long-held jer-sey number adversely influences a play-er’s psyche (in the sports sense), such that his or her performance on the field suffers. Thus, acquiring a long-held or previously held number with sentimen-tal value can boost a player’s psyche, or confidence. Goheen (2004) provides an additional anecdote involving a football player who acquired a previously held

TABLE 1. A Sampling of Jersey Transactions in Professional Baseball and Football

Buyer Team Seller In-kind item Value

(position) (jersey number) (position) (year of sale)

Sandy Alomar, Jr. Chicago White Sox Josh Paul home computer n/a (2000/2001)a

(catcher) (15) (catcher)

Tim Brown Tampa Bay Buccaneers Dave Moore n/a “let the wives . . .

(wide receiver) (81) (tight end) settle it . . .” (2004)b

Terrell Buckley Miami Dolphins Arturo Freeman n/a > $7,000 (with

(defensive back) (27) (defensive back) “incentives”) (2003)

Plaxico Burris New York Giants Jeff Feagles financed construction n/a (2005)c

(wide receiver) (17) (punter) of outdoor kitchen in

Feagles’ Arizona home

Roger Clemens Toronto Blue Jays Carlos Delgado Presidential Rolex watch $15,000 (1997)

(pitcher) (21) (first base)

Lee Evans Buffalo Bills Mark Campbell n/a $20,000 (2004)

(wide receiver) (83) (tight end)

Eddie George Dallas Cowboys Bruce Thornton n/a “Eddie will be writing

(running back) (27) (defensive back) him a check” (2004)d

Tom Glavine New York Mets Joe McEwing financed construction n/a (2003)e

(pitcher) (47) (outfield/2nd base) of a baby nursery in

McEwing’s home

Rickey Henderson Oakland A’s Ron Hassey “Substituted for n/a (1989)f

(outfield) (24) (catcher) Hassey at an

autograph session”

Rickey Henderson Toronto Blue Jays Turner Ward n/a $25,000 (1993)

(outfield) (24) (outfield)

Brian Jordan Atlanta Braves Fredi Gonzalez new motorcycle $40,000 (2005)

(outfield) (33) (3rd Base Coach)

Eli Manning New York Giants Jeff Feagles financed Feagles’ n/a (2004)g

(quarterback) (10) (punter) Florida family vacation

in Spring of 2005

Clinton Portis Washington Redskins Ifeanyi Ohalete n/a $40,000 (2004)h

(running back) (26) (defensive back)

Edgar Renteria Boston Red Sox David Wells n/a “a lot [of money]”

(shortstop) (3) (pitcher) (2005)

Michael Vick Atlanta Falcons Chris Mohr n/a $7,000 donation to

(quarterback) (7) (punter) Boys & Girls Club of

Thomson, GA (2001)i

Mitch Williams Philadelphia Phillies John Kruk 2 cases of beer n/a (1991)

(pitcher) (28) (first base)

Kellen Winslow Cleveland Browns Aaron Shea n/a < $20,000 (2004)j

(tight end) (80) (tight end)

aThis item (see Lowitt, 2001, para. 5) is likely valued at $3,000, or more.

bQuote attributed to Tim Brown, who indicated that the players’ wives would determine the transaction price (Flynn & Reynolds, 2004, para. 22). cA major home remodeling job would likely reach a five-figure sum, or more. Conservatively, this transaction is easily valued in the $3,500-$8,500 range

(see Eisen, 2005, para. 4; Pasquarelli, 2005, para. 8; Pearson, 2005, para. 5; Thomas, 2005, para. 3).

dQuote attributed to Lamont Smith, George’s agent at the time of the transaction (ESPN.com News Services, 2004, para. 24–25).

eA major home remodeling job would likely reach a five-figure sum, or more. Conservatively, this transaction is easily valued in the $1,000-$5,000 range

(Jenkins, 2005, para. 7).

fThe size of this transaction (see Lowitt, 2001, para. 14) is represented by the opportunity cost of Rickey Henderson’s time (in 1989) for the duration of the

event. Henderson’s salary in 1989 was $2,120,000. Using a full-time work week (2,080 hours), Henderson’s hourly wage was $1,019. Thus, the value of this transaction likely exceeded $2,000 (in 1989 dollars).

gThis trip is likely valued at $10,000, or more. In 2005, the Feagleses flew from New Jersey to Destin, where they rented a car and beach house for one

week (Eisen, 2005, para. 8–9).

hThe Portis-Ohalete agreement called for Portis to pay Ohalete $40,000 in three installments–$20,000 immediately (i.e., June of 2004), $10,000 by Week

8 of the 2004 NFL season, and $10,000 by 25 December 2004. Portis made the initial payment in June of 2004, but refused make the final two payments. Portis apparently believed the contract was voided when Ohalete was cut by the Redskins during August 2004 Training Camp and was claimed off waivers by the Arizona Cardinals. Ohalete filed suit in December of 2004 for the remaining $20,000. Portis agreed to pay Ohalete $18,000 in an out-of-court set-tlement in June of 2005 (Pasquarelli, 2005, para. 2, 10–14). Earlier in this saga, Portis indicated to the media that he had purchased a new car/other items ($45,000 total value) for Ohalete in exchange for the jersey number (Union-Tribune News Services, 2004).

(table continues)

number and revived his confidence in the process:

“Everything’s feeling better; I’ve got my number back,” said [Tory] James, the tall [Cincinnati Bengals] cornerback who wore #26 last season but has the more familiar #20 this year. “Something as simple as a number can make you feel different.” (Goheen, 2004, para. 2)

Our story builds on the phrase used by Goheen by considering the decision to purchase (acquire) a long-held or pre-viously held jersey number from a teammate as representing an investment in what we refer to as confidence capi-tal. As such, these jersey transactions represent much more (potentially) than novel examples of the market mecha-nism. These investments in confidence capital may, like other forms of human capital investment in sports that are dis-cussed in Leeds and von Allmen (2005), increase the player’s marginal product. The increase in marginal product from confidence capital investment will be exhibited through measures that con-tribute to victories (i.e., output). In base-ball, an investment in so-called confi-dence capital might manifest itself in a higher slugging average for batters and a higher strikeout-to-walk ratio for pitchers, resulting in more team wins. The increase in victories or output trans-lates into greater ticket or television rev-enue for the impacted franchise (Leeds & von Allmen; Scully, 1974). Thus, an increase in a player’s marginal product also increases the player’s marginal rev-enue product. Of course, it follows that if people can increase their productivity, they can increase their earnings (Leeds & von Allmen),

Although it is generally true that there is a positive relationship between a professional athlete’s marginal rev-enue product and his or her earnings,

there are a number of studies that dis-cuss the specific elements of sports labor markets (e.g., monopsony, reserve clauses, free agency, arbitration, and salary caps) and how these affect the marginal revenue product-earnings relationship (Leeds & von Allmen, 2005).

Some studies in the economics litera-ture provide empirical estimates of mar-ginal product and marmar-ginal revenue product in professional sports. Recent examples include Bruggink and Rose (1990), Brown (1993), MacDonald and Reynolds (1994), Scully (2004), and Depken and Wilson (2004). Classic pieces in this genre are Scully (1974), and Scott, Long, and Somppi (1985). Our previous discussion of the impact of confidence capital investment on the production process in professional sports follows the general construct in these classic pieces. The idea of confi-dence capital, as it relates to jersey num-bers, fits neatly into the conceptual framework for modeling marginal (rev-enue) product in sports.

Integrating the Jersey Transactions Example into Classroom Discussion

Most principles of economics text-books present a discussion of human capital and its relation to marginal prod-uct. For example, Mankiw (2007) states:

Human capital is the accumulation of investments in people. The most impor-tant type of human capital is education. Like all forms of capital, . . .[human cap-ital] represents an expenditure of resources at one point in time to raise pro-ductivity in the future. (p. 415)

Frank and Bernanke (2007) go fur-ther by stating that human capital is “an amalgam of factors such as education, experience, training, intelligence,

ener-gy, work habits, trustworthiness, and initiative that affect the value of a work-er’s marginal product.” (p. 405).

Our description of jersey numbers transactions as investments in confi-dence capital fits neatly into the amal-gam of factors listed in Frank and Bernanke. Students should naturally grasp the appropriateness of a human capital amalgam that ends, as an amend-ed Frank-Bernanke amalgam might, with trustworthiness, confidence, and initiative that affect the value of a work-er’s marginal product.

Most authors relate increases in pro-ductivity (marginal physical product) to increases in the value of marginal prod-uct, or marginal revenue prodprod-uct, and to increases in workers’ earnings. These lessons are often presented graphically in principles of economics texts (e.g., Frank & Bernanke, 2007). As part of a thorough coverage of the subject, Ekelund, Ressler, and Tollison (2006) provide a brief outline of factors that can change the demand for labor. This outline easily accommodates discussion of the relationships between confidence capital, the marginal product of labor, and the demand for labor. Use of this outline, along with the notion of confi-dence capital, enhances a graphical exposition. Of course, sports economics texts (e.g., Leeds & von Allmen, 2005), and labor economics texts (e.g. Ehren-berg & Smith, 2006) also provide avenues for introducing the jersey trans-actions lesson in courses for juniors and seniors.

NOTE

The authors thank two anonymous referees of this journal and Len Treviño for helpful comments, and Chris Mohr for providing one of the anecdotes used in this study. Any errors are our own.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Franklin G. Mixon, Jr., Depart-TABLE 1—(Continued)

iThis story was found in The Augusta Mirror, although the donation was an unreported sum. We obtained the $7,000 sum reported here through a phone

interview with Chris Mohr on August 4, 2005.

jThe Plain Dealer(Cleveland) reported in June of 2004 that Winslow was willing to pay Shea between $25,000 and $35,000 for #80. The deal was

final-ized in September of 2004, although neither Winslow nor Shea would reveal the ultimate transaction amount. Shea did state that the price was less than $20,000, or the amount that Lee Evans paid Mark Campbell for #83. Jenkins (2005) and Pearson (2005) report, instead, that Winslow gave Shea a package of suits (designer clothing), meals (free dinners), and a vacation (holiday) totaling around (said to be worth in the region of) $30,000 (Buffenbarger, 2004, para. 8; Union-Tribune News Services, 2004, para. 11–14).

ment of Economics and Finance, University of Southern Mississippi, 118 College Drive #5072, Hattiesburg, MS 39406.

E-mail: mixon@cba.usm .edu

REFERENCES

Becker, G. S. (1975). Human Capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Becker, G. S. (1996). Accounting for Tastes. Cam-bridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Becker, G. S., & Mulligan, C. B. (1997). The

endogenous determination of time preference.

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 729–758.

Boyes, W. J., & Happel, S. K. (1989). Auctions as an allocation mechanism in academia: The case of faculty offices. Journal of Economic

Per-spectives, 3, 37–40.

Brown, R. W. (1993). An estimate of the rent gen-erated by a premium college football player.

Economic Inquiry, 31, 671–684.

Bruggink, T. H., & Rose, D. R., Jr. (1990). Financial restraint in the free agent labor market for Major League Baseball: Players look at strike three.

Southern Economic Journal, 56, 1029– 1043.

Buffenbarger, K. (2004, June 1). AFC notes: “Cut day” anti-climactic this year. Retrieved August 24, 2006, from http://www.getsportsinfo.com/ index.php?page=football/featurearticles/afcnotes/ 060104

Cowen, T. (2004a, October 7). Markets in every-thing [Msg]. Message posted to http://www. marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/ 2004/10/markets_in_ever_2.html

Cowen, T. (2004b, February 11). Markets in every-thing [Msg]. Message posted to http:// www .marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/ 2004/02/markets_in_ever_1.html

Cowen, T. (2004c, February 20). Markets in every-thing [Msg]. Message posted to http://www .marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/ 2004/02/markets_in_ever_2.html

Depken, C. A., II, & Wilson, D. P. (2004). Labor markets in the classroom: Marginal product in Major League Baseball. Journal of Economics

and Finance Education, 3, 12–24.

Ehrenberg, R. G., & Smith, R. S. (2006). Modern

labor economics: Theory and public policy(9th

ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Eisen, M. (2005, April 1). What’s in a number? Ask Jeff Feagles! Retrieved July 19, 2005, from http://www.giants.com/news/eisen/story. asp?story_id=6149

Ekelund, R. B., Jr., Ressler, R. W., & Tollison, R. D. (2006). Microeconomics: Private and

pub-lic choice(7th ed.). Reading, MA:

Addison-Wesley.

ESPN.com News Services (2004, July 23). Sides met Friday at Valley Ranch. Retrieved August 25. 2006, from http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/news/ story?id=1844735

Flynn, J., & Reynolds, S. (2004, August 11). Training camp notebook: Wednesday. Pewter

Report. Retrieved August 25, 2006, from

www.bucmag.com/article.asp?action=detail& article=917&category

Frank, R. H., & Bernanke, B. S. (2007).

Princi-ples of Microeconomics(3rd ed.), New York:

McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Goheen, K. (2004, June 5). Bengals overhaul secondary. The Cincinnati Post.Retrieved Jan-uary 13, 2005, from http://www.cincypost. com/bengals/2004/bengsd06-05-2004.html. Jenkins, L. (2005, May 13). What is a number

worth? Some athletes pay the price. Retrieved August 3, 2005, from http://select.nytimes .com/gst/abstract.html?res=F00F15FB3A540 C708DDDAC0894DD404482&n=Top%2fRef erence%2fTimes%20Topics%2fPeople%2fG %2fGlavine%2c%20Tom

Jones, T. (2004, August 16). Uniform code: Be ready to pay. The Sporting News.Retrieved Jan-uary 13, 2005, from http://www.findarticles .com/p/articles/mi_m1208/is_33_228/ai_ n6158377

Leeds, M., & von Allmen, P. (2005). The

Eco-nomics of Sports. Boston: Addison Wesley.

Lowitt, B. (2001, April 12). Playing the numbers game: Players willing to pay to keep their iden-tities. The St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved August 13, 2004, from www.sptimes.com/ News/041201/Sports/Playing_the_Numbers_g. shtml+%22Playing+the+numbers+game%22+l owitt&hl=en&gl=us&ct=clnk&cd=1

MacDonald, D. N., & Reynolds, M. O. (1994). Are baseball players paid their marginal prod-ucts? Managerial and Decision Economics, 15, 443–457.

Mankiw, N. G. (2007). Principles of

Microeco-nomics(4th ed.). Mason, OH:

Thomson/South-Western.

Mixon, F. G., Jr., & Withers, M. C. (2004). The market for jersey numbers in professional

sports. Unpublished manuscript.

Pasquarelli, L. (2005, June 6). Portis agrees to pay Ohalete $18K. Retrieved July 19, 2005, from http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/columns/story? columnist=pasquarelli_len&id=2077548 Pearson, H. (2005, May 21). Look out for no. 1

and the shirt will look after itself. Retrieved June 27, 2005, from http://football.guardian.co.uk/ Columnists/Column/0,4284,1489196,00.html Rovell, D. (2003, December 2). LeBron, Carmelo

top NBA jersey sales. Retrieved January 13, 2005, from http://espn.go.sportsbusiness/s/ 2003/1202/1676476.html

Salguero, A., & G. Estwick. (2003, April 26). Dol-phins teammates’ swap is all about the num-bers. Retrieved August 25, 2006, from http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives Salary vs. marginal revenue product under monopsony and competition: The case of pro-fessional basketball. Atlantic Economic Journal 13, 50–58.

Scully, G. W. (1974). Pay and performance in Major League Baseball. American Economic

Review, 64, 915–930.

Scully, G. W. (2004). Player salaries and the dis-tribution of player earnings, Managerial and

Decision Economics, 25, 77–86.

Thomas, P. (2005, June 15). Transaction wire seems perfect for these deals. Retrieved August 25, 2006, from http://www.latimes.com/sports/ custom/morningbriefing/la-sp-briefing15jun15, 1,7485304.story?coll=la-headlines-sports-morning_br

Union-Tribune News Service. (2004, June 13). When the yips hit, fire your caddie. The San

Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved August 24,

2006, from www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/ 20040613/28.html