SMEs’ use of

languages

19

A n investigation into SMEs’

use of languages in their

export operations

Dave Crick

Department of Marketing, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK

KeywordsExport, Languages, SMEs, United Kingdom

AbstractT his paper reports on an exploratory investigation into the use of languages within UK small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) which are engaged in export activities. Results from a postal survey and subsequent interviews provide a contribution to the literature by reporting on empirical findings in relation to four areas: managers’ perceived importance and benefits of using foreign languages, issues preventing their use, the functional use of languages within businesses and issues affecting firms’ recruitment and training in respect of languages. T he results suggest that, although most firms are aware of the importance of languages and the benefits they can bring, this is not reflected in their use in certain functional areas and within the recruitment and training policies of many businesses.

Introduction

A s Herbig and Kramer (1991) point out: “T he world is growing smaller every day. If you are not attempting to sell your products overseas, you are surely being exposed to and competing against foreign-made products. T he growth of multinational business, the increasing interdependence of economies, the tremendous quantity of technology transfer, the world-wide communications capabilities and the frequent international exchanges have all created the need to understand better and interact with those from foreign cultures”.

Interestingly, the w ay in w hich particular firms communicate w ith individuals and organisations within foreign cultures has been shown to vary quite considerably. Indeed, depending on the situation in w hich the communication was undertaken, this has resulted in embarrassing situations for the companies concerned.

One of the most common forms of communication difficulties is normally considered to be the use of language. However, when dealing with the issue of language, its perceived meaning needs clarification in order to place it into context. For example, Swift (1991) points out that popular dictionary definitions of language are “speech”, “tongue of a people”, “words used in a branch of learning”, or “style of speech or expression”. Steiner (1977) broadens the definition by stating that language is “only one among a multitude of graphic, acoustic, olfactory, tactile, symbolic mechanisms of communication”.

It is, therefore, important not to restrict wider research studies involving communication issues to spoken language (see, for example, A lmaney, 1974; A rpan et al., 1974; Henderson, 1979; Ricks, 1983; Mintu-W imsatt and Gassenheimer, 1996), albeit this forms the basis of the investigation reported in

IJEBR

5,1

20

this paper. Indeed, Herbig and Kramer (1991) highlight particular problems associated with non-verbal communication, since on occasions, what words fail to convey is told through gestures and body movements. T hey point out that seemingly harmless and even mundane behaviour such as crossing one’s leg and exposing the soles of one’s shoes or putting hands in one’s pockets is, in some cultures, considered poor taste, offensive, and insulting towards the host.

A s such, Herbig and Kramer suggest that non-verbal communication can create “noise” within the cross-cultural communication process, i.e. something w hich disto rts the intended meaning. T hey prov ide ex amples w hereby executives may unknowingly create noise when dealing with other cultures: slouching, chewing gum, using first names, forgetting titles, joking, wearing too casual clothing, being overtly friendly towards the opposite sex, speaking too loudly, being too eg alitarian with the wrong people (usually lower class), working with one’s hands, carrying bundles, and tipping too much.

Examples such as these are affected largely by the context in which cross-cultural interactions take place. A lthoug h certain similarities may ex ist between particular countries in terms of their cultural norms, the likelihood that problems may occur will arguably increase where an interaction takes place with a person from a culturally more distant country. By way of example, Herbig and Kramer (1991) point out how noise may affect US/Japanese negotiations. T hey suggest that A mericans’ directness and their overbearing manner may sig nal to Japanese a lack of self-control and implicit untrustworthiness; at the very least they signal a lack of sincerity. T he authors go further to suggest that silence is another form of communication. W hereas it is irritating to certain western cultures, silence to the Japanese means one is projecting a favourable impression and is thinking deeply about the problem.

Turning now to the specific focus of this investigation, it is useful to consider the use of languages in international business operations, since this is perhaps the most obvious element of cross-cultural communication and a number of studies have stressed the importance of this issue (see, for example, Shane, 1988; Ferney, 1989; Holden, 1989; Edwards, 1990; Rushby, 1990; Swift, 1990; Metcalf, 1991; Schloss, 1991; Swift and Swift, 1992; Evening Standard, 1993; Miles, 1993; Linguatel, 1995a; 1995b; Marschan et al., 1997).

Research has shown that firms in some countries have faced more difficulties than others in this respect, some of which have relied too much on the use of English as a widely recognised “business language” internationally. Indeed, as Shipman (1992) points out, after Mandarin, English has the largest number of native speakers in the world – some 700 million people. Commenting on the results from a regional UK study the government reports that “recent research shows nearly 33 per cent of small to medium-sized companies in the north of England had encountered a language or cultural barrier. T his figure was almost twice as high as the one for comparable areas of Spain and Germany” (DT I, 1996a).

SMEs’ use of

languages

21

point, McIntyre (1991) provides an example cited in the Christian Science Monitor: “You can buy all the Hondas you want in the United States without knowing Japanese, but try to sell Buicks in Japan without the language and a knowledge of the culture. It just doesn’t work”.

After a review of the literature, Hagen (1988) concluded that the overwhelming message from all the studies was that UK companies were losing valuable trading opportunities for lack of the right skills in certain languages, and many without realising it. Consequently, it is within this context that this paper reports on selected aspects of SMEs’ use of languages in their export operations.

Literature review

A fter a recent empirical study undertaken in Wales, Peel and Eckart (1997) suggested that “larger firms consider language to be a more important export impediment than do SMEs”. T his observation seems peculiar given the greater financial and human resources which are usually at the disposal of larger firms. For example, one might expect that all things being equal, larger firms would be more willing to employ language specialists, finance language training schemes for staff, or even contract work out to specialists on an ad hocbasis to translate work in to and out of foreign languages. T herefore, questions could be raised in relation to the way in which such attitudes were reflected in firms’ performance, although a causal relationship is difficult to explain.

T he importance of languages to particular businesses and the way in which this manifests itself in co rpo rate policy has been well documented. Fo r example, Hagen (1992) points out that some companies are increasing their investment in language training. Christie’s, the art dealers, now require every employee to be fluent in at least one foreign language; Grand Metropolitan plc has decided to include data on language ability in their management review process, following a personnel audit. BA A plc and Hertz (UK) have introduced an incentives scheme to encourage their personnel to learn a language.

Clearly, while some companies have made a conscious attempt to improve their communication skills, others have not, in some cases with disastrous results. A s the DT I (1996b) point out, when the official receivers were called in to a company, they found a letter in the filing cabinet which was written in German. It was untouched because no one had understood the content. T he order found in the letter was large enough to have saved the company! T his is not to say that poor attitudes towards the use of languages will always have such dire consequences, but the same government report highlights a number of embarrassing situations which have arisen. For example, one company produced their technical specification and sales literature in several languages only to find they were claiming exceptional efficiency for their “watery sheep” (i.e. “hydraulic rams”). In another embarrassing incident, the entire British management of a Dutch subsidiary failed to turn up to the office party because the details had been posted up in Dutch.

IJEBR

5,1

22

controlled language test on London companies to see how they would respond to telephone enquiries from a foreign caller speaking French, German, Spanish, Italian o r “ Broken English” . It w as repo rted that many fo reig n callers were confused by expressions like “s-ringin-fer-yer” (“its ringing for you”), “putin-yerfru” (“putting you through”) and “lines-bizi-ye-old?” (“the lines are busy, will you hold?”). Over one-third of calls failed at the switchboard and foreign callers reported various rebuffs, including muffled nervous laughter, long silences and responses enunciated with a high level of decibels (DT I, 1996b).

Policy makers have been keen to highlight success stories associated with the use of languages. A s the DT I (1996c) point out, during an export drive, a battery producer from the north-west estimated that there was a 60 per cent increase in its sales after training 5 per cent of its workforce in French and German. In another example, one exporter of textile machinery in Gateshead had built a sales team of fluent Chinese, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, German and French speakers with customers in over 75 countries. Since 1990/1991 it had seen its turnover jump from £ 18.1m to £ 31m in 1992/1993. Policy makers have suggested (perhaps with an upbeat message which is unrepresentative) that this approach is typical of the way many small and medium-sized UK companies are successfully integrating a language capability with their export strategy (DT I, 1996a).

A lthough the issue of in-house language skills has been widely reported, the use of translation services has also been reported on within the literature. Ricks (1984) highlights the problem of the use of translation by focusing on one of Pepsi’s famous advertisements. He suggests that it should embody the general theme and concept rather than be an exact or precise duplication of the original slog an. Pepsi repo rtedly learned that its ad “come alive with Pepsi” was literally translated into German to mean “come out of the grave with Pepsi”. In A sia, it was translated as “bring your ancestors back from the dead”.

Interestingly, an additional though perhaps less publicised problem with translation is that of sabotage, whereby a false or misleading translation may take place for some reason, usually associated with commercial gain. Ricks (1984) provides an example of a US company which may have been the victim of translation sabotage. T he firm tried to sell its products in the former Soviet Union with the help of a Russian translator. T he company innocently displayed a translated poster in Moscow which, it soon discovered, said the company’s oil-well equipment was good for improving a person’s sex life. T his said, however, the use of “backtranslation” by an independent language specialist has been commonly suggested in the literature to avoid the problem of literal translation or indeed translation sabotage (see many international and cross-cultural texts for more details).

Research focus

SMEs’ use of

languages

23

of foreign languages in their businesses, although this should not be removed from an appreciation of the particular cultural environments in which firms operate, i.e. in addition to simply a linguistic ability! Nevertheless, this paper is restricted to factors associated with SMEs’ use of languages rather than issues associated with culture in a broader sense. Within this, although the factors are inter-linked, the salient issues concerning languages within firms can arguably be grouped into two core areas of concern, namely those relating to usage and training. With this in mind, the specific issues within this study build on these two core areas and focus on four themes: managers’ perceived importance and benefits of using foreign languages, issues preventing their use, the functional use of languages within businesses, and issues affecting firms’ recruitment and training in respect to languages.

Within the SME sector, it would be rather restrictive from an analytical viewpoint to present only frequencies of responses, since this would not account for variations within the study relating to particular categories of firms. However, although there is no single ag reed method by which to categorise particular sizes of firms (Storey, 1994; Carson et al., 1995) – indeed, different statistical results are likely to result from particular subjective classifications – the categories in this paper were determined after discussions with policy makers in the joint export promotion directorate (JEPD) in relation to firms’ number of employees.

Methodology

It should be noted that since this paper repo rts on one part of a w ider investig ation, the methodological approach undertaken is similar to that reported elsewhere. T he wider study addressed a number of other issues, for example, whether differences exist between firms with varying deg rees of ex po rt involvement, b ut this paper is restricted to differences between particular sized SMEs in order to provide a more applied focus to the analysis undertaken.

A fter reviewing the pertinent literature in this area of investigation, a draft postal questionnaire was constructed incorporating the major issues of interest. Subsequently, it w as show n to several managers w ith responsibility fo r exporting and academics deemed knowledgeable about the subject area. In determining a sampling frame for this investigation, it was decided to restrict this study to firms with fewer than 250 employees since it was considered that larger firms with greater human and financial resources would be more likely to employ language specialists and consequently skew the results of the research. However, it was considered important that the study be restricted to firms that were only engaged in export activities and therefore it was decided that non-exporters and those firms with overseas subsidiaries should be excluded from the study to act as a control mechanism within the methodological approach undertaken.

IJEBR

5,1

24

Consequently, it was decided to use a database developed from respondents to a recent study of exporting manufacturers, although the original database from which this was compiled was the Sells Export Directory. Furthermore, the questionnaire used in the previous study from which the database was compiled had a filter question to determine the ethnic origin of the owner of the firms, since this had been an area under investig ation. In the course of the investigation reported in this paper, the study was restricted to firms owned by “white European” executives in an attempt to reduce cultural bias associated with language use (further precise questions on ethnicity-related issues were considered inappropriate to avoid racial effects on response rates).

W hen undertaking the p ostal survey, 400 firms were draw n from the previously mentioned database; this figure was derived from an assumption that about a 25 per cent response rate would be achieved prov iding approximately 100 firms (see most classic research texts for average response rates to postal surveys). T his was considered manageable since the database was compiled from previous respondents to a survey and therefore, all things being equal, the firms had a sympathetic attitude towards responding to ex po rt-related survey s. In total, 185 firms completed the questionnaire providing a response rate of 46.25 per cent after two mailings. Interviews were subsequently undertaken with the executives with responsibility for exporting (typically the owner/managing director) in 20 firms representing particular sizes of firms and with various export ratios in order to obtain a more in-depth perspective of issues surrounding their behaviour in respect to language use. A lthough a figure of 20 interviews was primarily based on time and cost limitations, it was considered representative of the overall sample since it was approaching 10 per cent of the responses to the postal survey. It should also be noted that after undertaking the 20 interviews, similar issues were discussed. Consequently, it w as concluded that diminishing returns in so far as establishing new information would have been the result of increasing the number of interviews.

Findings

In undertaking the analysis within this investigation, it was observed that the response rates for the particular categories of firms used by the JEPD were in fact found to be skewed as follows: g roup 1 = 1-9 employees (34 responses); g roup 2 = 10-49 (70); g roup 3 = 50-99 (56); and g roup 4 = 100 to 249 (25). Nevertheless, whereas it could be argued that the g roups might be merged to even out the skewed response rate (especially since they were based on subjective classifications any w ay ), it w as decided that this would be inappropriate since they were based on the JEPD’s categorisations.

SMEs’ use of

languages

25

the functional use of languages within businesses; and, fourth, issues affecting firms’ recruitment and training in respect to languages.

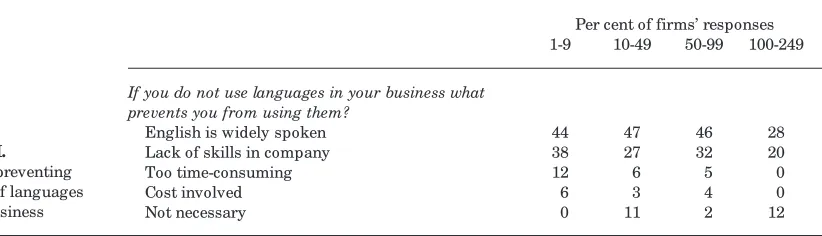

Commencing with the firms’ perceived importance and benefits of foreign languages, the findings are summarised in Table I. Using analysis of variance between the mean responses, it can be observed that no statistical difference was found to exist between the firms, with all four g roups indicating, in aggregate terms, that languages were important in their businesses. In terms of how languages benefit/might benefit their businesses, it was interesting to note that many firms, and particularly very small ones, perceived that this might enhance their image and to a lesser extent increase orders; an increase in competitiveness was not viewed as a benefit by the majority of firms. Reasons for these perceived benefits, in addition to the obvious issues of a willingness to do business in a customer’s language and because customers prefer to do business in their own language, involved avoiding misunderstandings and the fact that it provided an indication of the quality of the business. Even so, reasons why firms did not use languages are shown in Table II. Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of firms indicated that this was because English is widely spoken; lack of skills within the companies was also seen to be a factor, and in particular, by very small firms.

Firms’ mean responses

1-9 10-49 50-99 100-249 Fratio Fprob

How important do you believe

languages are in your business? 1.97 2.10 2.03 1.92 0.402 0.751

Responses were rated as follows: 1 = very important; 2 = important; 3 = not very important; 4 = irrelevant

Per cent of firms’ responses 1-9 10-49 50-99 100-249

How do you think languages benefit/might benefit your business?

Enhance image 76 67 64 48

Increased orders 64 40 38 48

Increased competitiveness 13 20 22 12

Languages do not benefit 0 13 13 12

W hy do you think languages benefit/might benefit your company?

It shows a willingness to do business in the

customers’ language 88 80 82 88

Avoids misunderstandings 71 50 48 48

A n indication of the quality of the business 50 31 57 52 Because customers prefer to do business in their

own language 41 51 63 48

Table I.

IJEBR

5,1

26

Turning now to the ex tent to whic h fo reig n lang uages were used within businesses, the results are detailed in Table III. Only one statistical difference was observed between the mean responses concerning the extent to which business departments/functions use languages and this was in relation to the receptionist/switchboard; this, perhaps surprisingly, was rated slightly higher by the smaller firms. T his said, the only department/function which had a mean score above the mid-point on the rating scale for any of the groups of firms was sales and marketing. Clearly, this suggests that most firms do not make too much use of languages within most of their departmental areas. However, within specifically the sales and marketing function, the most widely used areas were seen to be personal selling and exhibitions, particularly by very small firms. For the company as a whole, the major areas in which languages were used tended to be foreign travel and received correspondence.

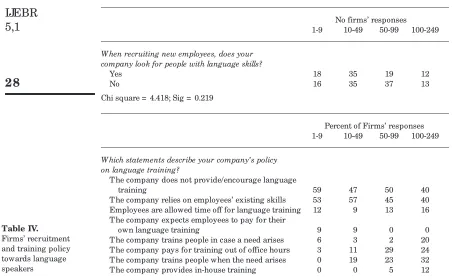

Finally, in terms of firms’ recruitment and training policy towards language speakers, the findings are detailed in Table IV. A s far as recruitment was concerned, no statistical difference was observed between the groups of firms in relation to whether firms look to recruit new employees with language skills. In so far as training was concerned, the statements which best reflected firms’ training policies tended to be that the company does not provide/encourage language training and that they rely on employees’ existing skills. T his was particularly the case w ith very small firms w hereas their larger-sized counterparts were more likely to provide and pay for language training.

Discussion

T he purpose of the exploratory investigation reported in this paper was to obtain a basic understanding of SMEs’ behaviour and perceptions with respect to the use of languages within their businesses. T he issues within this study focused on four themes: managers’ perceived importance and benefits of using foreign languages, issues preventing their use, the functional use of languages within businesses, and issues affecting firms’ recruitment and training in respect to languages.

In short, it was observed that, in aggregate terms, the sample of firms rated the importance of language use rather highly and most recognised the major

Per cent of firms’ responses 1-9 10-49 50-99 100-249

If you do not use languages in your business what prevents you from using them?

English is widely spoken 44 47 46 28

Lack of skills in company 38 27 32 20

Too time-consuming 12 6 5 0

Cost involved 6 3 4 0

Not necessary 0 11 2 12

Table II.

SMEs’ use of

languages

27

benefits brought about by their use. However, of those firms which did not use languages, it was worrying to observe that many responded by stating this resulted from the fact that English was widely spoken. Indeed, the personal interviews which followed the postal survey found evidence to support the work of W hitty (1987), namely, that some managers recruited overseas agents

Firms’ mean responses

1-9 10-49 50-99 100-249 Fratio Fprob

In which business departments/ functions does your company use foreign languages and to what extent?

Sales and marketing 2.52 2.42 2.48 2.68 0.457 0.712 Secretarial/administration 1.86 1.94 1.82 1.70 0.514 0.673 Support services 1.74 1.44 1.44 1.37 2.073 0.105 Receptionist/switchboard 1.65 1.70 1.23 1.50 6.317 0.000 Distribution 1.65 1.57 1.32 1.31 2.617 0.052 A ccounting/legal 1.52 1.50 1.45 1.31 0.635 0.593 Production/technical 1.51 1.54 1.42 1.47 0.463 0.708

Responses were rated as follows: 1 = never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = often; 4 = very often

Per cent of firms’ responses 1-9 10-49 50-99 100-249

If languages are used in the sales and marketing function, in which areas?

Personal selling 85 67 73 60

Exhibitions 74 57 45 60

Public relations 29 14 21 36

Promotional literature 21 19 32 64

Special promotions 21 6 7 40

Direct mail 15 17 5 20

Packaging 12 16 10 24

Branding 0 3 0 8

Market research 0 17 14 8

A dvertising 0 16 18 32

For the company as a whole, in which of the following areas are foreign languages used?

Foreign travel 82 60 70 76

Received correspondence 53 64 75 72

Outgoing correspondence 41 40 60 60

Outgoing telephone calls 38 54 70 64

Meetings 32 33 32 44

Received orders 32 70 59 48

Presentations 32 23 9 32

Received telephone calls 29 63 61 48

Others (please state) 0 3 4 0

Table III.

IJEBR

5,1

28

on the basis of their language ability stating that this was to some extent almost as important as their ability to sell overseas!

However, this depended to a large extent on the complexity of the product in question since it was pointed out by some respondents that agents, and indeed in some cases translators, might have problems in conveying a working-business translation. Instead, and supporting the findings of Hagen (1988), it was suggested that a literal translation of technical standards and the like might be conveyed incorrectly by non-product specialists. T his had resulted in the use of either in-house staff with linguistic abilities, especially in relation to personal selling and attendance at exhibitions overseas, or external specialists with linguistic and technical knowledge.

With non-complex items, the need for in-depth product knowledge, i.e. outside of a basic understanding, may be less important. Here, language ability in gaining a competitive edge might still prove very important. For example, one firm noted that the switchboard operator had been trained in the basics of several languages. On recognising a particular language, the call would be put through to the salesperson with the appropriate linguistic ability. Consequently, the problem of customers being put off by the use of broken English and an unprofessional attitude towards overseas calls was hopefully minimised (DT I, 1996b).

No firms’ responses 1-9 10-49 50-99 100-249

W hen recruiting new employees, does your company look for people with language skills?

Yes 18 35 19 12

No 16 35 37 13

Chi square = 4.418; Sig = 0.219

Percent of Firms’ responses 1-9 10-49 50-99 100-249

W hich statements describe your company’s policy on language training?

T he company does not provide/encourage language

training 59 47 50 40

T he company relies on employees’ existing skills 53 57 45 40 Employees are allowed time off for language training 12 9 13 16 T he company expects employees to pay for their

own language training 9 9 0 0

T he company trains people in case a need arises 6 3 2 20 T he company pays for training out of office hours 3 11 29 24 T he company trains people when the need arises 0 19 23 32 T he company provides in-house training 0 0 5 12

Table IV.

SMEs’ use of

languages

29

Unfortunately, most firms pointed out cost implications associated with the recruitment and training of language specialists and this was reflected in an approach far removed from the previous example. Indeed, many firms did not look to recruit language specialists or indeed support training for staff. In pragmatic terms, this approach can be fully appreciated given the lack of resources facing many smaller firms; also, the fact that some firms may have low export ratios and not see language specialists as a worthwhile investment. Even so, perhaps in an idealistic setting, firms might be encouraged to be more responsive to recruitment and training practices in respect of the use of languages in exporting and an understanding of general cultural matters as well. In doing so, the impact of cross-cultural interference affecting translation may be reduced (Brislin, 1978).

Specifically, foreign language capability “shows an interest in the culture and customer’s country and often smoothes the path of negotiation by facilitating social contacts; allows a relationship of trust to develop; improves the flow of communication both to and from the market; improves ability to understand the ethos and business practices of the market; improves ability to negotiate and adapt product and service offerings to meet the specific needs of the customer; and gives a psychological advantage in selling” (Turnbull, 1981). A rguably, SMEs might do well to recognise such issues if a competitive edge is to be obtained in dealing with operations within overseas markets.

In reality, however, it is debatable whether smaller firms will be customer driven in their lang uage practices fo r some time to come and their competitiveness in international markets may be affected by this. W hile there may be a potential lack of awareness by some managers regarding the full importance of dealing in a foreign language, the extent to which a number of those who claimed to recognise the importance are actually reacting to this is questionable. In turn, this demonstrates a lack of international marketing orientation by managers of some SMEs and it may prove beneficial to become more customer focused. In particular, this focus extends to support staff such as those in secretarial and receptionist positions who may be the first port of call for potential orders or at least general communication. Nevertheless, with the number of business g raduates with linguistic abilities increasing, likewise, T ECs and Business Links supporting training initiatives such as the “Investors in People” award, employment and training of staff within this context may prove beneficial to firms in the future. T his might especially be the case within SMEs which have a large proportion of business in overseas markets. In the meantime, policy makers appear to need to bridge the gap between some SMEs’ perceived importance of language use and actual implementation of strategies to address this within their firms. Issues such as this provide an interesting basis for future studies which might take this work forward.

References

IJEBR

5,1

30

A rpan, J.S., Ricks, D.A . and Patton, D. (1974), “T he meaning of miscues made by multinationals”,

Management International Review, Vol. 14 No. 4-5, pp. 3-11.

Brislin, R.W. (1978), “Contributions to cross-cultural orientation programs and power analysis to translation/interpretation”, in Gerver, D. and Sinaiko, H. W. (Eds), Language Interpretation and Communication, Plenum Press, New York, NY.

Carson, D., Cromie, S., McGowan, P. and Hill, J. (1995), Marketing and Entrepreneurship in SMEs: A n Innovative A pproach, Prentice-Hall, Hemel Hempstead.

Department of Trade and Industry (1996a), Trading across Cultures, DT I, London.

Department of Trade and Industry (1996b), Business Language Strategies, DT I, London. Department of Trade and Industry (1996c), Business Language Training, DT I, London.

Edwards, G. (1990), “It’s OK, they all speak English”, International Business Communication, Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 8-12.

Embleton, D. and Hagen, S. (Eds) (1992), Languages in International Business: A Practical Guide, Hodder & Stoughton, London.

Evening Standard(1993), “Breaking all language barriers”, 22 November.

Ferney, D. (1989), “Language skills: is reactive training enough?”, Journal of European Industrial Training, Vol. 14 No. 9, pp. 27-30.

Hagen, S. (1988), Languages in Business: A n A nalysis of Current Needs, Newcastle Polytechnic, Newcastle.

Hagen, S. (1992), “Language policy and strategy issues in the New Europe”, Language Learning Journal, Vol. 5, pp. 31-4.

Henderson, N. (1979), “Doing business abroad: the problem of cultural differences”, Business A merica, 3 December, pp. 8-9.

Herbig, P.A . and Kramer, H.E. (1991), “ Cross-cultural negotiations: success throug h understanding”, Management Decision, Vol. 29 No. 8, pp. 19-31.

Holden, N.J. (1989), “Towards a functional typology of languages in international business”,

Language Problems and Language Planning, Vol. 13 No. 1.

Linguatel (1995a), Survey of Language Capabilities of Exporters in Mainland Europe.

Linguatel (1995b), A Survey into the A bility of Major UK Exporters to Handle Foreign Language Enquiries.

McIntyre, D.J. (1991), “W hen your national language is just another language”, Communication World, May, pp. 18-21.

Marschan, R., Welch, D. and Welch, L. (1997), “Language: the forgotten factor in multinational management”, European Management Journal, Vol. 15 No. 5, pp. 591-8.

Metcalf, H. (1991), Foreign Language Needs of Business, Institute of Manpower Studies Report No. 215.

Miles, L. (1993), “A n Englishman abroad”, Marketing Business, March, pp. 30-4.

Mintu-Wimsatt, A . and Gassenheimer, J.B. (1996), “Negotiation differences between two diverse cultures: an industrial seller’s perspective”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 20-39.

Peel, M.J. and Eckart, H. (1997), “Export and language barriers in the Welsh SME sector”, Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 4, pp. 31-42.

Ricks, D.A . (1983), Big Business Blunders: Mistakes in Multinational Marketing, Irwin. Ricks, D.A . (1984), “How to avoid business blunders abroad”, Business, April-June, pp. 3-11. Rushby, N. (1990), “Beyond the language lab”, Personnel Management, February, p. 71.

Schloss, S. (1991), “From lay-bys to languages”, Industrial Society Magazine, June, pp. 16-17. Shane, S. (1988), “Language and marketing in Japan”, International Journal of A dvertising, Vol. 7,

SMEs’ use of

languages

31

Shipman, A . (1992), “Talking the same languages”, International Management, June, pp. 68-71.Steiner, G. (1977), A fter Babel: A spects of Language and Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Storey, D.J. (1994), Understanding Small Business, Routledge, London.

Swift, J.S. (1990), “Marketing competence and language skills: UK firms in the Spanish market”,

International Business Communication, Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 22-6.

Swift, J.S. (1991), “Foreign language ability and international marketing”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 25 No. 12, pp. 36-49.

Swift J.S. and Swift, J.W. (1992), “A ttitudes to language learning”, Journal of European Industrial Training, Vol. 16 No. 7, pp. 7-15.

Turnbull, P. (1981), “Business in Europe: the need for linguistic ability”, Occasional Paper, UMIST.