DOI: 10.4018/978-1-4666-2842-7.ch016

Chapter 16

Diana Chalil

University of Sumatra Utara, Indonesia

Assessment of

Smallholders’ Barriers

to Adopt Sustainable

Practices:

Case Study on Oil Palm (Elaeis

Guineensis) Smallholders’

Certification in North

Sumatra, Indonesia

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

ORGANIZATION BACKGROUND

Sustainable Agriculture

Agricultural has long been an important sector of human life It supplies food, fibers, fuel and raw materials for various industriesandwith increasingpopulationand income levels, demands for agricultural products have also increased. This has lead to a shift from the traditional agricultural patterns towards the more intensiveone. The results intensive agricultural practices have been quite impressive, but they have not always sustainable. For example, in the 1940s the shift known as the Green Revolution, marked the development of high-yield hybrid crops, however, they required the useof extensive fertilizers, pesticides and large quantities of irrigation water. While high-yield hybrid crops increased crop production by almost 3% per year over the period 1961-2004, unintended consequences included excessive ex-ploitation of land and water, and a subsequent decrease in production and profit. For example, in 1961-1963 the average Asian farmer’s fertilizer use was 6 kg/ha (2.5 kg/acre), four decades later, in 2000-2002, it increased more than 20-fold to 143 kg/ha (57.9 kg/acre) (WorldBank, 2008). As a result, the production costs increased and the profit decreased. It was found that an increase in fertilizer price caused a sharp decline in rice yield growth in Asia from 2.6% in 1970 to only 1.5% in 1980 (Kassie and Zihali, 2009).

Giampietro (1994) argued that such technological advances cannot be defined as unsustainable development, which includesnot only productionefficiency and profitability, but also social responsibility and environmental soundness. In fact, genetic engineering tended to address the first two criteria, but was usually not compatibility withother human activities and natural ecosystem processes. The situation is exacerbated when agricultural products are not only grown to meet thefood needs of a country, but are alsoa source of export revenue. For Indonesia, palm oil is recorded as an important export revenue contributor, with an export value of US$109 million in 1981, increasing to US$1.6 trillion in 2009 (Directorate Generale of Estate, 2012).

The Indonesian Palm Oil

Indonesia is the largest palm oil producer in the world producing more than 21 million tons of Crude Palm Oil (CPO) or 46.7% of the total world production. On average, 61% of the Indonesian palm oil is exported to the international market. Increased CPO demands in the international markets incentivize CPO producers to continue increasing their productions, both by improving productivity and expanding production areas. Today, of 43 countries worldwide cultivating oil palm Indonesia has seen the fastest expansion. While the global plantings of oil palm grew eight-fold in the past decade, the cultivation in Indonesia increased 23 times over the same period. In 1980s about 100,000 hectares were under oil palm cultivation, this number doubled in the 1990s. The planted areas recorded about 100,000 hectares of annual growth and doubled in the 1990s. Between 1999 and 2003, demand for palm oil drove expansion to a total of 500,000 hectares, most of which was facilitated by converting forest into oil palm plantations (Chandran, 2010 in Teoh, 2010).

Therefore, palm plantations are often considered a major cause of environmental damages, such as rapid destruction of forests and their biodiversity (van Gelder, 2004; Wakker 2004). This issue has provoked strong feelings among environmen-talist and some have even asked to boycott the use of palm oil products. However, this is likely to be ineffective, as demands for palm oil products keep increasing from both domestic and industrial consumers.The demand for palm oil will likely continue because of its low production costs and and continous supply.Compared to other vegetable oils, palm oil average production cost is very low. Palm oil crops use only 0.26 ha (0.64 acre) of land area to produce 1 ton of palm oil, while soy-bean, sunflower and rapeseed require 2.2 ha (5.4 acres), 2 ha (5 acres) and 1.5 ha (3.7 acres) respectively. Palm oil can be harvested throughout the year, generating nearly 10 times the energy it consumes, while soybean is a seasonal crop and only produces 2.5 of the energy (World Growth, 2009). Palm oil also has a high melting point, has proven to have low o trans-fatty acids content, a rich source of carotenoids andvitamin E, (all vegetable oil has no cholesterol), and is entirely genetically modi-fied (GM) free (Climate Avenue, 2010). Hence, boycotts will not sustainably solve the environmental problems caused by palm oil production.

far from the efficient scale (Siregar, 2011). Unfortunately, some of those who have not converted their paddy fields encounter problems in maintaining their field. The oil crops tend to decrease water supply for the paddy fields. Previous studies show that oil palm crops need a lot of water supply to optimally grow. On average, the water requirement for oil palm crops is 0.9 lt/sec/ha (0.36 lt/sec/acre) (Harahap and Darmosarkoro, 1999 in Wignyosukarto 2010) or 12-25 lt/trunk/day (Amri, 2004 in Lestari, 2010; Medan Bisnis, 2006). With a decrease in water supply, farmers could no longer continue to cultivate paddy. Therefore, when the conversion starts in one field, usually other adjacent fields will also be converted into oil palm plantations (Chalil, 2011). The land conversion decreases the rice supply. In Indonesia, such a conversion becamea serious problem because rice (that is milled from paddy), is the staple food for most people. However, closing the palm oil plantations is not rational because of their beneficial and increasing market potential.

RSPO and Sustainable Practice

To address such issues, oil palm business management needs to give more attention to sustainable practice. This idea has been formulated in many concepts and agree-ments, including the Roundtable Sustainability of Palm Oil (RSPO). This agreement is composed of 8 principles, 39 criterias and 77 sub criteria. RSPO forum recognised that applying all of these P&C would not beeasy, especially for smallholders who tended to have more technical, financial, capacity and organisational challenges than their larger competitors. In response, RSPO formed a Task Force on Smallholders (TFS) to ensure that smallholders could manage and produce CPO in line with the RSPO P&C. RSPO also adjusted the requirements to suit the production systems and circumstances of smallholders. Major stakeholders such as Governmental agencies (e.g. Ministry of Agriculture, Indonesian Palm Oil Conference (IPOC), Non Gov-ernment Organizations (e.g. Sawit Watch, WWF-Indonesia), Growers (Gabungan Pengusaha Kelapa Sawit Indonesia (GAPKI)/The Assosiation of Indonesian Palm Oil Businessmen and its nucleus companies), and Smallholders’ representatives (Asosiasi Petani Kelapa Sawit Indonesia/The Assosiation of Indonesian Palm Oil Smallholders, Asosiasi Perkebunan Inti Rakyat/The Assosiation of Nucleus Estate Smallholders, Serikat Petani Kelapa Sawit/Palm Oil Smallholders Union) were involved to develop specific P&C interpretation for smallholders.

national specificification. As of 2011, eight (8) countries have completed their own National Interpretation of P&C for smallholders, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Colombia, Ghana, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Island and Thailand.

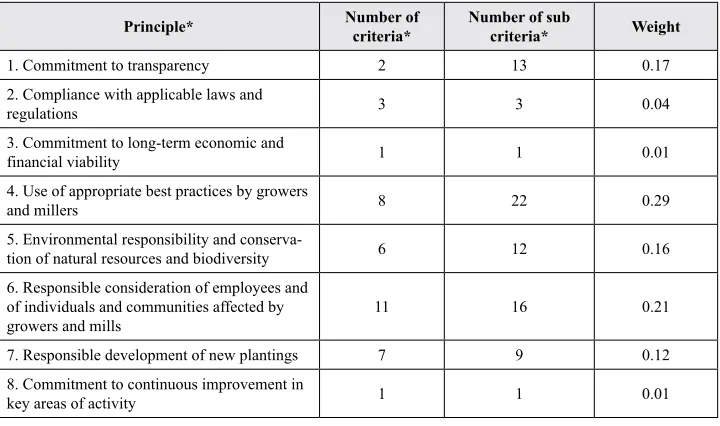

Among the 39 criteria in the RSPO P&C, 3 are considered irrelevant for small-holders. These are criteria 5.4 regarding “the use of energy efficiency and renewable energy use,” criterion 5.6 regarding “the availability of plans to reduce pollution and emissions” and criterion 6.6 on the obligation “to respect the company and fa-cilitate the right of all employees become union members.”Each of the sub criteria is used as the basis to assess the RSPO certification process. Each of the eight (8) principles in the RSPO P&C does not have the same number of criteria and sub criteria; therefore each principle is weighted differently.The details can be seen in the following table.

Suprisingly, Table 1 shows that the greatest weight does not lie on the environ-mental responsibility aspect (Principle 6). Rather it gives more weight on the best practices by growers and millers (Principle 4) and responsible consideration of employees and community (Principle 6). The smallest weight lies on the commit-ment to long-term economic and financial viability (Pinciple 3), the commitcommit-ment to continuous improvement (Principle 8) and compliance with applicable laws and regulations (Principle 2). If we compare these weights to the smallholders’ exist-ing condition, thepriorityseems to fit the needs of smallholders to improve their performance. Many of the smallholders have not implemented the best practices.

Table 1. Weight of RSPO principles

Principle* Number of criteria* Number of sub criteria* Weight

1. Commitment to transparency 2 13 0.17

2. Compliance with applicable laws and

regulations 3 3 0.04

3. Commitment to long-term economic and

financial viability 1 1 0.01

4. Use of appropriate best practices by growers

and millers 8 22 0.29

5. Environmental responsibility and

conserva-tion of natural resources and biodiversity 6 12 0.16 6. Responsible consideration of employees and

of individuals and communities affected by

growers and mills 11 16 0.21

7. Responsible development of new plantings 7 9 0.12 8. Commitment to continuous improvement in

key areas of activity 1 1 0.01

The usage of uncertified seeds (that are produced in the smallholders own nursery) is common (Figure 1). Therefore, their productivity is lower than those of the state and private plantations. In 2011, onaverage, smallholders only reach around 15 tons of Fresh Fruit Bunches (FFB, output from the oil palm crops/ha/year, while that of private and state plantations have reached 20-25 tons FFB/ha/year (8.09-10.11 tons FFB/acre/year), with 21%-23% of CPO rendemen (Herlina, 2011).

The purpose of RSPO certification is to promote the growth and the use of sus-tainable oil palm. The term “sussus-tainable” refers to economic, social and environ-mental sustainability. Based on her review of various literatures, Partzsch (2011, p.419) suggested that “the RSPO criteria define sustainable palm oil but are far from being consensus.” Inspite of the failure to clearly define the “sustainable” terminol-ogy, each type of the sustainability criteria can be directly related to aRSPO sub criteria. The detail can be seen in the following table.

Table 2 shows that among the 36 relevant criteria, 14 are directly related to the environmental sustainability, while 13 to social responsibility. Economic sustain-ability seems to have less priority, because they are only directly related to 2 of the criteria. Companies that can meet these principles and criteria (P&C) will obtain RSPO certificates. As of 2011, RSPO had 441 registered members comprising oil palm growers, processors, traders, manufacturers, banks, investors and non-gov-ernmental organizations. However, of the ninety-eight (98) oil palm growers, only twenty-nine (29) have been certified, although all of them are big companies with long experience in the industry (RSPO, 2011). This indicates that the adoption and diffusion of RSPO criteria practices is slow, and is limited even among big

nies. Although each group of growers possess inadequate oil palm plantation size, as a group their total land area is almost 40% of the total world oil palm areas and contribute more than 30% of the total world supply (Vermeulen and Goad, 2006). This shows that smallholders are no longer minor players and have significant contribution to the industry.

Smallholders and the RSPO

Agricultural innovation is defined as new ideas, methods, practices or techniques which provide the means forachieving sustained increases in farm productivity and income (Adams, 1987). Innovations are not only limited to the general and genu-inely new things that have not been created or used previously anywhere, but it can also be ideas, methods, practices or techniques that are new to a group of people or community.The innovations themselves can be divided into commercial and non commercial. The former refers to innovations that are developed to address eco-nomic challenges, while the latter tended to tackle environmental unsustainability. Thus environmental innovations use techniques, methods and approaches to focus more on improving land or water management rather than simply increase farm productivity. Many of the RSPO principles and criteria (P&C) relates to sustain-able oil palm plantation management practices, such as limiting the use of chemical fertilisers, maintaining the water quality, maintaining the biodiversity, or avoiding the use of fire for land preparation, methods which are still new for smallholders. Therefore, the RSPO P&C can be seen as an environmental innovation for palm oil smallholders in Indonesia.

In Indonesia, smallholders can be divided into supported/schemed and independent growers. Initially, smallholders were only a small group with a total ownership of 3125 hectares or 20.1% of the Indonesian total palm oil industry in 1979. However, in just decades, their totalareas have reached more than 3 million ha (7.41 million acres) or 40% of the Indonesia total oil palm plantations in 2009. Unfortunately, the rapid area expansion was not accompanied by increased performance efficiency. In general, smallholders still tended to lack technical knowledge. Many of them

Table 2. Type of sustainability in the RSPO sub criteria

No Types of Sustainability Sub Criteria

1 Economics 3.1; 6.10

could not distinguish between poor and good seeds, and periodically purchased low yielding seedlings. Others still planted their crops on steep areas without terracing, or did not follow the proposed fertilizer application rates.

Smallholders also tended to lack managerial skills. In general, their plantation sizes were less than the efficient scale: on average, supported smallholders’ individual plantations are less than 5 ha (12.36 acres), while those of the independent are less than 20 ha (49.42 acres). On average, the economies of scale of an oil palm planta-tion is at least 4000 hectares, so that it can supply a mill that processes the fresh fruit bunches into crude palm oil (WRM, 2004). Without sufficient economies of scale, both supported and independent smallholders are unable to operate with minimum costs to reach the optimal income. Owners tended to lack the required skill sets to carry out breakeven analysis and therefore they do not have the information to plan for improvements. All of these conditions make it difficult for smallholders to meet the RSPO P&C requirements. Therefore, the certification was only granted to large growers initially. However, with their increasing numbers, many parties involved in the palm oil industry agreed that smallholders’ role can not be ignored. Hence at the 8th annual meeting in 2010, RSPO members agreed to pay more attention to

smallholders and declared “RSPO is also for smallholders” as the meeting theme. Recognizing different conditions and charateristics between smallholders and other producer groups, the general RSPO P&C was then specially interpreted and modified for smallholders. However, even assessed with the special interpretation, only two smallholder groups, both from the supported/schemed smallholders (PT Hindoli, Cargill and Musim Mas Group), have successfully managed to obtain the RSPO certificate as of 2011.

the Indonesian Government develop its own certification (Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil/ISPO). In fact, ISPO criteria are not sigficantly different from those of the RSPO: The obvious difference is only in the depth of the law and regulations as-sessment. ISPO assess the law and regulation in 7 specific sub criteria, while RSPO only address it in 1 general criterion (criterion 2.1) (RSPO, 2007 and ISPO, 2011).

In general, Indonesian smallholders have not given much attention to environ-mental issues. The only environment friendly practice that has been widely applied among farmers is the organic crop farmings. However, the development is relatively slow because the market response is inadequate, both in terms of price and quantity. In general, smallholders still focus on the effort to increase their production level and short term income rather than to respond to the environmental problems and long term benefit. Many smallholders still lack capital to buy production inputs, hence have not used optimum input level. To address this, the Indonesian govern-ment often subsidizes fertilizer price. Unfortunately, this makes farmers tend to over use chemical fertlizer.

Influencing Factors of the Adoption

Many factors affect the process of adoption and diffusion. They are not only fac-tors that relate to the innovation itself, but also that to the communication process and the condition of the receivers. Previous empirical studies found that factors that relate to the innovation include the complexity, incompability, flexibility and profitability of implementing the innovation. Innovations that are more triable and observed, or more compatible with climate environment and biomass availability, or more flexible and need less implementation cost and capital outlay, would be easily adopted or diffused. Factors that relate to the communication factors include the communication channel and the social system, such as the access to information, generation and spread of information, social and physical infrastructure, policies or institutional and political constraints. Factors that relate to the conditions of receivers include the intellect and knowledge, economic factors and land tenure (Rogers, 1995 in Adams, 1987; Vanclay and Lawrence, 1994; Baide, 2005; Kassie and Zikhalil, 2009).

Objectives of the Study

While the contribution of oil palm smallholders is of growing importance, their performance, compared to their competitiors, is relatively low. Therefore, if the smallholders are going to be involved in the world’s palm oil industry through the RSPO certification, their conditions and characteristic needs must be empirically studied. Despite concerns over the relevancy of RSPO and sustainable practices, to date no studies have been undertaken to investigate the cause of slow develop-ment in obtaining the RSPO certification, especially among oil palm smallholders. Therefore this study was conducted (1) to analyse the smallholders’ characteristics (2) to determine the smallholders’ level of adoption of the RSPO P&C, (3) to analyze the correlation between smallholders level of adoption to their characteristics, and (4) to analyze the factors that impede the adoption of RSPO P&C.

DATA AND RESEARCH METHOD

This study was conducted in North Sumatra, a province of the first and largest oil palm areas in Indonesia. In this province two (2) districts, namelyAsahan and Labuhan Batu Selatan (Labusel), were selected since they consisted of the larg-est number/concentration of palm oil smallholders. Data were collected through interviews with sixty (60) smallholders that were randomly selected. Smallholders from Asahan represented the independent smallholders, while those from Labusel represented the schemed/supported smallholders. Schemed/supported smallholders are growers who cultivate palm oil with with the support of either the state or big private plantations. The support could be technical assistance through trainings or supervision, or financial assistance such as providing loans for buying seeds, fertil-izers and pesticides.

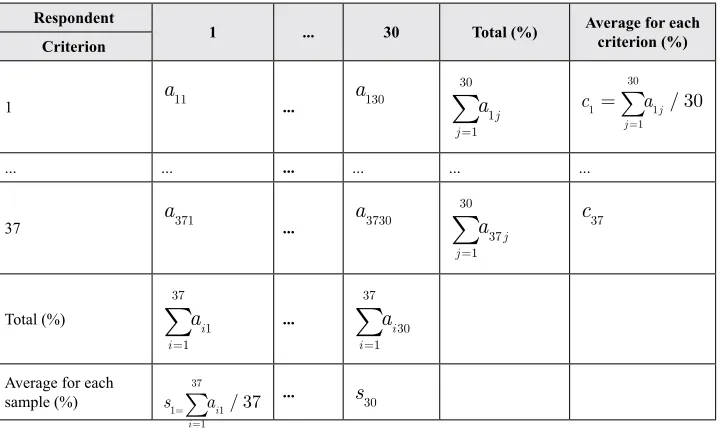

The level of adoption data were measured through 77 indicators and parameters of the 37 RSPO sub criteria. Each of the sub criteria equals one if the respondent applied the indicator and parameter, and zero otherwise. The level of adoption for each criterion in each of sample is measured with a n

m

ij = ,where i= 1,...., 37

(number of criteria), j = 1,...,30 (number of respondent for each district), ni= total

assessment value for criteria i and m

i =number of sub criteria for criteria i. Each

criterion does not always consist of the same number of sub criteria. Using aijfrom all samples, the average value of level of adoption for each sample is determined

with s

a

j

ij

=

∑

37 ,and the average value of level of adoption for each criterion is

determined with c

.The description can be seen in Table 3.

ciis then used to determine the score of each criterion for each district in

Labu-han Batu and AsaLabu-han. The score is divided into 5 levels, which are: (a) 0% -19%, (b) 20% -39%, (c) 40% -59%, (d) 60% -79% to (e) 80% -100%, referring to score 1 to 5, respectively. Score 1 represents the very low level of adoption, while 5 refers to the very high level of adoption.

Table 3. Level of adoption estimation matrix

s

iis then used as the level of adoption variable and correlated with the

charac-teristics data in order to determine association between the factors. The Spearman Correlation test is used to estimate the association of: (a) age, (b) formal education, (c) farming experience, (d) number of dependents, (e) land area, (f) income, (g) cosmopolitan rate, and (h) participation rate to smallholders’ level of adoption to the RSPO P&C. The land area is expected to have a positive sign, especially if the innovation is related to the production factor efficiency. Age is expected to have a negative sign; as young smallholders are expected to be more risk taker in trying new things. Education is expected to have a positive sign because it can affect the smallholders’ ability to understand the potential advantages of adopting the innova-tion. Income is expected to have a positive sign because it can also affect the abil-ity of adopters to finance or bear the risk of the innovation. Number of dependents is expected to have a negative sign because it is also associated with the ability of adopters to bear the risks of innovation. The participation rate in institutional and the cosmopolitan levels are expected to have positive signs because they might relate to the transfer of information, which might change the adopters’ way of think-ing (Soekartawi, 2005). The level of association is divided into 3 levels of relation-ship from weak, moderate, to strong relationrelation-ship with range of correlation value of 0-0.33, 0.34-0.66 and, 0.67-1, respectively.

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

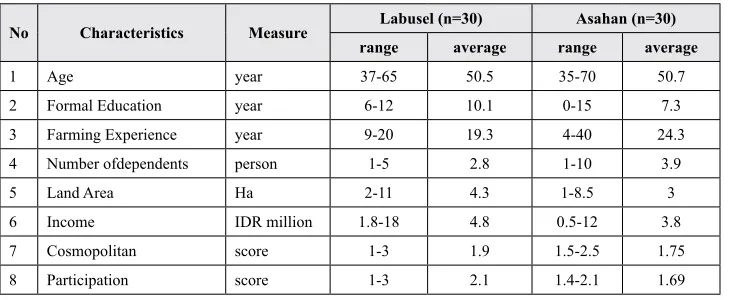

Smallholders’ Characteristics

From interviews with 60 respondents in Labusel and Asahan, characteristics of palm oil smallholders can be described as follows.

less than 2 ha (4.94 acres). Comparing to the schemed smallholders, indepedndent smallholders have longer experience in farming. However, without sufficient land size and capital to buy inputs, their productivity and income are lower than those in Labusel. With more dependents, their income might not be enough to support the whole family expenditure.

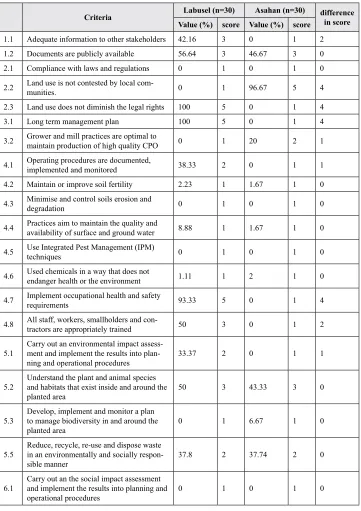

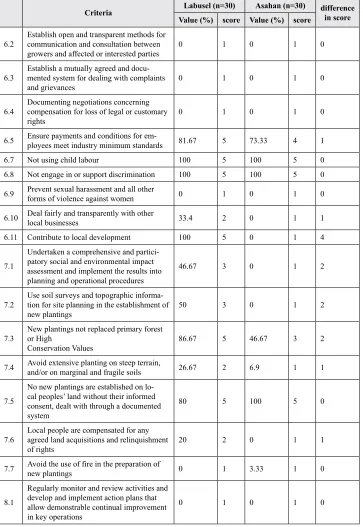

The Assessment of Level of Adoption

The assessment of smallholder level of adoption was measured by their ability to fulfill sub criteria in each of the RSPO criteria. It was measured in percentage, with average values and average scores of each criteria of each group is as follows.

Table 5 shows that some of the RSPO criteria have not been implemented at all among smallholders, both in Labusel and Asahan, which is shown by the 0% values (criteria 2.1 for example). In contrast, a number of the RSPO criteria have been completely implemented among both of them, which is shown by the 100% values (criterion 6.7 for example). Labusel has 13 (35%) of 0% value and 5 (13.5%) of 100% value, while Asahan has 21 (57%) of 0% value and 3 (8.1%) of 100% value. This indicates that supported smallholders (Labusel) tend to have farming practices that are more similar to those of the independent ones (Asahan). Although in many area (20 criteria) they still have similar farming practices.

Correlation between Smallholders Characteristics and their

Level of Adoption

On the one hand, the smallholder level of adoption in Labusel is higher than those in Asahan. Labusel also has higher incomes, land areas, cosmopolitan levels, par-ticipation levels and education than the latter, while the opposite applies for age

Table 4. Characteristics of smallholder samples

No Characteristics Measure Labusel (n=30) Asahan (n=30) range average range average

1 Age year 37-65 50.5 35-70 50.7

2 Formal Education year 6-12 10.1 0-15 7.3

3 Farming Experience year 9-20 19.3 4-40 24.3

4 Number ofdependents person 1-5 2.8 1-10 3.9

5 Land Area Ha 2-11 4.3 1-8.5 3

6 Income IDR million 1.8-18 4.8 0.5-12 3.8

7 Cosmopolitan score 1-3 1.9 1.5-2.5 1.75

continued on following page

Table 5. Assessment values and scores

Criteria Labusel (n=30) Asahan (n=30) difference in score Value (%) score Value (%) score

1.1 Adequate information to other stakeholders 42.16 3 0 1 2 1.2 Documents are publicly available 56.64 3 46.67 3 0

2.1 Compliance with laws and regulations 0 1 0 1 0

2.2 Land use is not contested by local com-munities. 0 1 96.67 5 4

2.3 Land use does not diminish the legal rights 100 5 0 1 4

3.1 Long term management plan 100 5 0 1 4

3.2 Grower and mill practices are optimal to maintain production of high quality CPO 0 1 20 2 1

4.1 Operating procedures are documented, implemented and monitored 38.33 2 0 1 1

4.2 Maintain or improve soil fertility 2.23 1 1.67 1 0

4.3 Minimise and control soils erosion and degradation 0 1 0 1 0

4.4 Practices aim to maintain the quality and availability of surface and ground water 8.88 1 1.67 1 0

4.5 Use Integrated Pest Management (IPM) techniques 0 1 0 1 0

4.6 Used chemicals in a way that does not endanger health or the environment 1.11 1 2 1 0

4.7 Implement occupational health and safety requirements 93.33 5 0 1 4

4.8 All staff, workers, smallholders and con-tractors are appropriately trained 50 3 0 1 2

5.1 Carry out an environmental impact assess-ment and implement the results into

plan-ning and operational procedures 33.37 2 0 1 1

5.2 Understand the plant and animal species and habitats that exist inside and around the

planted area 50 3 43.33 3 0

5.3 Develop, implement and monitor a plan to manage biodiversity in and around the

planted area 0 1 6.67 1 0

5.5 Reduce, recycle, re-use and dispose waste in an environmentally and socially

respon-sible manner 37.8 2 37.74 2 0

6.1 Carry out an the social impact assessment and implement the results into planning and

Table 5. Continued

Criteria Labusel (n=30) Asahan (n=30) difference in score Value (%) score Value (%) score

6.2 Establish open and transparent methods for communication and consultation between

growers and affected or interested parties 0 1 0 1 0

6.3 Establish a mutually agreed and docu-mented system for dealing with complaints

and grievances 0 1 0 1 0

6.4 Documenting negotiations concerning compensation for loss of legal or customary

rights 0 1 0 1 0

6.5 Ensure payments and conditions for em-ployees meet industry minimum standards 81.67 5 73.33 4 1

6.7 Not using child labour 100 5 100 5 0

6.8 Not engage in or support discrimination 100 5 100 5 0

6.9 Prevent sexual harassment and all other forms of violence against women 0 1 0 1 0

6.10 Deal fairly and transparently with other local businesses 33.4 2 0 1 1

6.11 Contribute to local development 100 5 0 1 4

7.1

Undertaken a comprehensive and partici-patory social and environmental impact assessment and implement the results into planning and operational procedures

46.67 3 0 1 2

7.2 Use soil surveys and topographic informa-tion for site planning in the establishment of

new plantings 50 3 0 1 2

7.3 New plantings not replaced primary forest or High

Conservation Values 86.67 5 46.67 3 2

7.4 Avoid extensive planting on steep terrain, and/or on marginal and fragile soils 26.67 2 6.9 1 1

7.5

No new plantings are established on lo-cal peoples’ land without their informed consent, dealt with through a documented system

80 5 100 5 0

7.6 Local people are compensated for any agreed land acquisitions and relinquishment

of rights 20 2 0 1 1

7.7 Avoid the use of fire in the preparation of new plantings 0 1 3.33 1 0

8.1

Regularly monitor and review activities and develop and implement action plans that allow demonstrable continual improvement in key operations

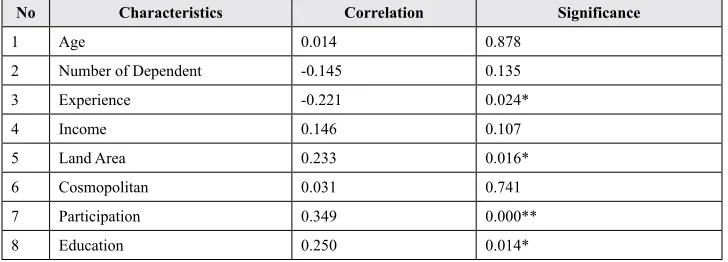

and number of dependents. To test the level of association between the level of adoption and these factors, Spearman correlation test was conducted, which result shown in Table 6.

The result shows that experience, land area, level of participation and level of education are significantly related to the smallholders’ level of adoption. However, all of them have correlation values less than 0.67, indicating that none have a strong association. Experience, land area and education have a weak association, while the level of participation has a medium association.

The experience correlation has a negative sign, showing that smallholders with longer experience in farming tend to have lower levels of adoption. It is expected that experience will improve smallholders’ knowledge and skills, thus they will fulfill more of the RSPO P&C. In fact, most smallholders still practice similar farming practice from time to time. However, even supported smallholders that had been trained previously no longer fully practice all of their knowledge about the good agricultural practice.

The land area correlation has a positive sign, showing that smallholders with bigger land area tend to have more farming practice that suit with the RSPO P&C. This happens because they have more income and capital to support the cost outlay for the farming practice.

Education correlation has a positive sign, indicating that the higher the small-holders’ education the higher their level of adoption will be. Smallholders with higher education are likely to have more knowledge about environment, regulation or safety work that is required in the RSPO P&C.

Similarly, the level of participation also has a positive sign, indicating that the higher the smallholders’ level of participation, the higher their level of adoption will be. The level of participation is measured by smallholders’ participation in

coopera-Table 6. Correlation between smallholders’ level of adoption and their characteristics

No Characteristics Correlation Significance

1 Age 0.014 0.878

2 Number of Dependent -0.145 0.135

3 Experience -0.221 0.024*

4 Income 0.146 0.107

5 Land Area 0.233 0.016*

6 Cosmopolitan 0.031 0.741

7 Participation 0.349 0.000**

8 Education 0.250 0.014*

tives and/or farmer groups. In fact, much information is shared and many activities are coordinated throughout these institutions. Compared with other characteristics, the level of participation has a higher correlation with smallholders’ level of adop-tion. Therefore, it can be said that improving these institutions’ performance and smallholders’ participation might improve the process of adoption of sustainable practice such as RSPO P&C.

DISCUSSION

Barriers to Adoption

Lack of Information for Smallholders

From 36 criteria that are relevant to smallholders, the supported smallholders’ aver-age level of adoption in Labusel is higher than independent smallholders in Asahan, which are 34.24% (score 2) and 18.56% (score 1), respectively. However, with less than 39% of fulfillness, both groups are still considered “low level of adoption.” In fact, many of the smallholders have not even heard about the RSPO yet, although some of them live adjacent to the certified large plantations that have notice boards on the edge of the estates.

For supported smallholders in Labusel, 12 criteria (33.33%) still have a value of 0%, and only 15 criteria (41.67%) have a value above 39% (the minimum percent-age to be considered “moderate”). For independent smallholders in Asahan, this is even worse, with 0% value appears in more than half of the criteria (21 criteria, which equal with 58.33% of the total number of criteria), and only 7 (19.44%) have values above 39% (Table 5). The 0% value means that none of the require-ment indicator and parameter in the criteria is fulfilled by the repondents. In fact, many of these criteria are associated with respondent knowledge, for examples the knowledge about chemical fertilizers and pesticides that are allowed, or about the types of animals and plants that are protected, or the laws and regulations that are related to oil palm plantations management.

Cost of Adoption

spent pesticides containers. Among the 30 independent smallholder respondents, only 7% buried the containers. The others just left them in the planting areas, some sold them to the recycle agents and some even threw them into the river. In fact, most respondents are fully aware that the used containers still have toxic material and should not be used anymore or thrown to the river. However, they do not bother to bury them because the suggested treatment needs some additional work and there is currently no incentive. Most of them manage their farm by themselves and only hire additional workers only for harvesting the FFB. This means that smallholders only have a limited time to undertake additional work. In contrast, when small-holders can get additional income by selling the waste, smallsmall-holders are willing to expend more effort. This can be seen in the way they handle the used fertilizer sacks. Many smallholders wash the used fertilizer sacks in the river and sell them to waste agents. Smallholders understand that the chemical fertilizers can pollute the river, but since they need to expend more effort to avoid it and the impact is not immediately visible, the practice continues.

Another example can be seen in their chemical fertilizer usage. Many of them only use chemical fertilizer and no manure from the very beginning of growing oil palm trees. They realize that they need to increase the dose from time to time as the soil condition tends to degradate, and manure can improve the soil structure. However, the manure is not locally available in adequate quantity and if they buy it from other places, it has an expensive transportation cost. Vanclay and Lawrence (1994) suggest that additional implementation costs of an innovation appear to be the rational consideration for smallhoders not adopting environmental innovations. Smallholders are likely to adopt innovations that suit their income and financial capabilities (Adams, 1987).

Incompatibility

still have 0% value for criterion 2.3. Another example is criterion 3.1 which deals with the requirement for having annual plan that is based on farming development data, and the land and topographic surveys. These records and documents are too complex for smallholders.

Adams (1987) suggested that compatibility with the stage of farm develop-ment is one of the factors that determine the level of adoption. “The reluctance of a smallholder to adopt a certain innovation may indicate that the smallholder has not reached the appropriate stage of development and does not see the practice as essential for the continuing development of his enterprise” (Adams, 1987). On av-erage, respondents’ formal education is up to elementary level, and they also have small land areas with relatively simple and routine activites. These might explain their reluctance to keep records and documents. However, this does not necessar-ily reflect their understanding about agriculture in general and oil palm plantation business in particular, or their objections to try something different. On average, respondents have planted oil palm crops for almost 15 years, some have done so for 26 years. Before planting oil palm crops, most of them have planted rubber crops for about 10 years. When many large companies began to open oil palm plantations, smallholders realized that the business has good prospects and without any appeal smallholders convert their farms into oil palm plantations. In contrast, smallhold-ers have not seen essential benefits they could gain from completing records and documents, so that they do not bother to apply them.

The other reason for not having records and documents is the incompability with social values. This can be seen in criteria 6.3, 6.4 and 7.6 which stated that all claims and negotiations between smallholders and the surrounding community need to be recorded. In fact, none of the smallholders have serious problems and unsolved negotiation with other community members. Most of the processes are solved through traditional kinship abritration. In such approaches, recording and documenting is often considered as lack of trust and could disturb the negotiation process. Therefore, recording and documenting are rarely done for claims and negotiations.

Inadequate Managerial Skills

In general, smallholders possess a small size of oil palm planting area. RSPO defines oil palm producers as smallholders if they have a planting area size less than 50 ha. In fact, supported smallholders only obtain 2 ha (4.94 acres) of planting area. Similar conditions appear among independent smallholders where most have less than 4 ha (9.88 acres). With such a plantation size, smallholders often have diffi-culties, both technically and financially, in applying sustainable practices such as those in the RSPO P&C requirements. This includes the difficulties in conducting a number of trainings and monitoring the implementation of the practices. In Indone-sia, such problems are often addressed by perfoming group activities. A number of reseachers believe that group activities have a number of good attributes that adds to farmers adopting more sustainable practices. First, it could not only be effective in improving farmers’ knowledge but also in changing their attitude (van den Ban and Hawkins; Adams 1988 in Musyafak and Ibrahim, 2005). Moreover, group ac-tivities could also overcome the benefit-cost-problem of adopting environmental innovation. Usually the benefits of sustainable practice are often social, thus the costs of adoption of environmental innovations should not be borne by individuals (Vanclay and Lawrence, 2007). In the draft of “National Interpretation of RSPO P&C for Supported Smallholders” and “National Interpretation of RSPO P&C for Independent Smallholders,” the supported smallholders will be facilitated by

ner companies, while the independent smallholders are facilitated by government agencies. But both groups need competent smallholders’ group leaders to coordinate and communicate with their facilitators.

One successful example of the former can be seen in the PT Hindoli case, which received RSPO certification for 8797 farmers. The group’s management is handled by using a hierarchy system. PT Hindoli utilized cooperation (KUD), to coordinate a number of farmer group alliances (Gapoktan). Each Gapoktan coordinates some farmer groups, and finally each group coordinates a number of smallholders. PT Hindoli established a Farmer Development Department that provided trainings and technical support, and employed six (6) full-time Farmer Development Assistants that have daily involvement with the smallholders. This shows that intensive management is really important in determining the success of the adoption process. Norman et al. (1997) stated that sustainable agricultural practices could only be successfully applied if they were arranged in an intensive management style. Unfortunately, in-tensive management is unlikely to appear among groups of the respondents. Fourty percent of the respondents admitted that the KUDs and the groups are still running but not with an intensive management style. For independent smallholders, more than 60% of them do not even participate in the KUD or farmer groups.

Profitability

Theoritically, certified growers and manufacturers should gain at least two advan-tages. First, they will get premium prices, and second they will get an increase in demand. These will give them extra revenues, which are expected to overcome extra expenditures occured in preparing and proposing the certification. However, except for the European importers, most buyers do not differentiate between certified and the non-certified FFB or CPO. Unfortunately, the greatest demand is not coming from European buyers (5.3 million metric tonnes), but from India (7.25 million metric tonnes) and China (6.3 million metric tonnes) (Mundi, 2011). In 2004-2009, the average annual import from India and China contributed 41.90% of the total export volume from Indonesia. In 2009, both countries recorded 48.38% of the Indonesian export share, while all of the EU countries only absorbed 18.66% (Department of Industry and Trade of Indonesia, 2009).

not. However, non-Europen consumers, including the two biggest consumers, India and China, are unlikely to pay higher prices for the certified palm oil. Therefore, in general the certified palm oil price has not been significantly differed to the non-certified ones (Ginting, 2011). Both enjoy a similar increase in their export price and demand. Similar results appear in the average difference test between a company’s selling price and quantity before and after getting the certificate. Without premium price, producers cannot compensate for the extra expenditures, which do not incen-tivize them to apply RSPO P&C. However, it is expected that in the long run when certified palm oil products are widely demanded, the RSPO certification might give significant advantages. One of the certified companies stated that although higher profit has not been received yet in the short term, with the increasing operational efficiency which resulted from the implementation of the RSPO P&C, they expect to gain more efficient and more environmentally and socially responsible production processing in the long term (Tiong et al, 2010). This implies that during the transi-tion period producers need to have enough capital to overcome extra expenditures without realizing any extra revenue. However, most smallholders often do not have enough capital to undergo the transition period.

Theoritically, independent smallholders are expected to receive higher market prices, since they are free to choose whether to sell their FFB to agents or to CPO mills. In contrast, supported smallholders can only sell their FFB to their joint CPO mills. In fact, the mill prices are often higher than the agents. However, smallholders rarely directly sell their FFB to the mill because, individually, most of them only produce a small amount of FFB. In addition, their plantations are far away from the mill location and thus it is not efficient to directly bring their FFB to the mills. On average, smallholders’ plantations are located around 10 km (6.21 miles) from the CPO mills. Therefore, independent smallholders just sell the FFB to local agents (Figure 3). These agents do not sort and grade the FFB, so farmers receive the same price for both high and low quality FFB. Smallholders have no bargaining power in determining the price, even if they have the better quality FFB. However, more

than 70% of the respondents keep selling their FFB to the same agents because other agents also offer similar prices. Moreover, they also have received some loans during the immature period, thus need to sell their FFB to the same agents to pay the loans.

SOLUTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

RSPO P&C is designed to support sustainable practices among oil palm smallholders. The principle and criteria may be technical, but the adoption of the practices is not only determined by technical factors. In this case, they are influenced by economic factors such as costs outlay and profitability in adopting the practices. In addition, they are also influenced by social factors such as smallholders’ knowledge and managerial skill, or social values of their surrounding community. These factors determined smallholders’ level of adoption of the practices. Therefore, ignoring social and economic factors may create barriers for smallholders in adopting the practices. In contrast, accomodating these factors is expected to accelerate the adop-tion process. Based on the results, some alternative soluadop-tions and recommendaadop-tions are proposed.

Sustainable Practices Need to Consider Potential Profit

For most smallholders, their oil palm estate is their main income source. Although many of them have not run their estate in the most efficient way, potential profits are still likely to be their main consideration in making their business decisions. This means that in general, smallholders would only apply new farming practices if they expect the results of the new practices would increase their revenue (for example, through the improvement of output quality) or decrease costs (for example, through the improvement of efficiency). Therefore, in order to accelerate the adoption of sustainable practice, smallholders need to have a sufficient level of confidence about the potential profit. Smallholders that produce certified FFB should gain more demand and higher price.

man-age individual smallholders action as a group, thus as a group they can reach suf-ficient economies of scale and bargaining power. However, as has been previously described, most of the groups are not active, and smallholders still individually run their business. Currently, the government has regularly determined the FFB price for each region in Indonesia. However, smallholders still often get lower prices than the determined ones. Most smallholders have no bargaining power, and prices are merely determined by local buyers. They argue that smallholders FFB quality is low, as they have not consistenly harvested their FFB based on certain maturity level. Smallholders’ output quality varies from individual to individual, and from time to time. Local buyers do not standardize and grade the FFB, thus smallholders have no incentive to improve their quality.

Sustainable Practices Need to Consider Organisational Aspect

Organisational aspect refers to both the structural and management factors. The process of adopting RSPO P&C involves a lot of participants, whom have various differences among them. Coordinating such a group requires good structural arrange-ment and managerial skills. PT Hindoli has successfully obtained the smallholders certificate and has shown that before applying the management system, the company needs to establish a good and clear organization structure. The bureaucracy is to maintain the increase in efficiency. Daily operational functions that need individual approaches are conducted by smallholders group, while conceptual functions that need a comprehensive approach are conducted by the company. After this, all man-agers are trained to ensure that they have fully understood all of their management functions, including the coordination of participants from different management levels. Using this as a model means that in the intitial process, the government or big companies needs to facilitate smallholder groups to choose competent leaders. Then they need to be trained, so that they will have the ability to make good plans (short and long term), organizing and actuating smallholders and other stakehold-ers to realizing the plans, and monitoring and controlling them as a sustainable improvement process. In the initial stage, the government and big companies might also need to support the groups with some funds and experts, or with some access for the groups’ relevant networking.

Sustainable Practices Need to Consider

Long Term Participation

in the long term the company expects to improve efficiency and offset the costs (Tiong et al, 2008). In other words, sustainable practice is not a sudden result but a process with several stages, from establishing knowledge, persuasion, making decision and confirmation. To maintain the sustainable practice as a smooth and improved process, stakeholders need to have a strong commitment. This means that the sustainable practices need to be designed as an entity with several stages, and each of them is designed to reach a part of the final goal. As a sequence, results in each stage are evaluated, and then are used as a base for the next period’s plan and strategy. Ideally, most stakeholders need to be involved through the whole stages. Pretty (1995 in Bruges and Smith, 2008) concludes that “a more sustainable agricul-ture with all its uncertainties and complexities, cannot be envisages without a wide range of actors being involved in continuing processes of learning.” Unfortunately, they found that many of the contributions of agricultural sustainability projects are often limited in the short term. To address such conditions, the whole activities and their evaluations of the projects need to be well recorded and documented. Hence, the process will keep moving towards the final goal.

To realise this, a long term plan with a clear and measurable aim is needed. Then, this plan needs to be completed with a good short term plan that elaborates methods to reach the final goal, step by step, and needs to be evaluated from time to time based on the smallholders’ improvement. In other words, although, the whole RSPO P&C criteria are treated as an entity, the adoption process is partly undertaken based on the smallholders’ development stages. This plan will help the management to organise and actuate the right person in the right position. Each person in charge needs to have legal positions to guarantee them that they will arrange the activity until the final stage. Besides this, all stakeholders, from smallholders or not, need to have the same mind set that the project is an effort to realising a final goal rather than treating it just as a temporary and responsive project.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTION AND CONCLUSION

Future Research

that the result will be more robust. Further research is also needed to improve the estimation. With a richer data set, the estimation would not only be limited to the descriptive and correlation analysis, but also the analytical and regression analysis. In particular, probabilistic estimation methods such as logistic regressions could potentially improve the estimation results, which would not only cover the sign but also the magnitude of estimations. This could show the smallholders’ propobability of adopting the RSPO P&C in various conditions and characteristics. Finally, fur-ther research is also needed to assess the impact, covering all the social, economic and environmental impacts of adopting sustainable practices in RSPO P&C. A comparison study between groups of smallholders that have and have not received certificate is also needed.

CONCLUSION

The tremendous increase of oil palm planting areas has raised issues concerning the sustainability of the cultivation practices. A number of alternative solutions have been suggested in order to address the issues. Among them, RSPO forum suggested some principles and criteria that can be used as guidance for producers. In fact, many of them are not easy to be adopted by palm oil producers, especially for the smallholders. This study indicates a number of barriers for adopting the principles and criteria, including technical, economical and social factors. A number of al-ternatives are proposed to overcome the barriers. The study needs further research to improve and complete the findings, to provide future insights into promoting sustainable practices among oil palm smallholders.

REFERENCES

Adams, M. E. (1987). Agricultural extension in developing countries. Singapore: Longman Scientific and Technical.

Baide, J. M. R. (2005). Barriers to adoption of sustanable agriculture practices

in the South: Change agents perspectives. Published Master Thesis, Auburn

Uni-versity, Alabama U.S. Retrieved January 27, 2012, from http://etd.auburn.edu/etd/ handle/10415/878

Bruges, M., & Smith, W. (2008). Designing a policy mix and sequence for mitigating agricultural non-point source pollution in a water supply catchment. Water Source

Management, 25(3), 875–892.

Bryan, B. A., & Kandulu, J. M. (2011). Participatory approaches for sustainable agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values, 25(1), 13–23.

Chalil, D. (2011). Oil palm, land conversion, food security and market power.Global

Bio-Pact Newsletter, 3. Retrieved January 16, 2012, from http://www.globalbiopact.eu

Climate Avenue. (2010). Palm oil: Demand and controversy. Retrieved January 14, 2012, from http://www.climateavenue.com/en.biod.palm.exp.demand.htm

Directorate General of Estate. (2011). Export and Import in Indonesia. Retrieved May 26, 2012, from http://ditjenbun.deptan.go.id/cigraph/index.php/viewstat/ exportimport/16-kelapa%20sawit

Dradjat, B. (2009).Menimbang Relevansi Sertifikasi RSPO. Warta Penelitiandan

Pengembangan Pertanian, 31(6). Retrieved January 17, 2012, from http://pustaka.

litbang.deptan.go.id/publikasi/wr316096.pdf

Giampietro, M. (1994). Sustainability and technological development in agri-culture: A critical appraisal of genetic engineering. Bioscience, 44(10), 677–689. doi:10.2307/1312511

Ginting, S. M. (2011). Analisis Komparasi Pendapatan Antara Perkebunan Ber-sertifikatdengan Perkebunan Tidak Bersertifikat roundtable on sustainable palm oil. Published Master Thesis, University of Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia. Herlina. (2011). Genjot Produktivitas, Pemerintah Jalankan Peremajaan Lahan

Kelapa Sawit. Retrieved January 10, 2012, from http://industri.kontan.co.id/news/

Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO). (2011). Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit

Indone-sia Berkelanjutan (IndoneIndone-sian Sustainable Palm Oil): Persyaratan (requirement).

Indonesia: Draft ISPO Pembahasan. Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil.

Kassie, M., & Zikhali, P. (2009).Sustainable land management and agricultural

practices in Africa: Bridging the gap between research and farmers. Brief for the

Expert Group Meeting, 16-17 April 2009, Gothenberg, Sweden.

Lestari, M. (2010). Kabut Asapdan Penegakan Hukum Lingkungan. Retrieved December 5, 2011, from http://riaupos.co.id/new

Medan, B. (2006, March 26).Irigasi Tidak Berfungsi, Petani Tapsel Alihkan

Tana-man Panganke Kelapa Sawit. Retrieved December 5, 2011, from http://www.

Mundi, I. (2011). Palm oil imports by country in 1000 MT.Retrieved December 20, 2011, from http://www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palm-oil&graph=imports.

Musyafak, A., & Ibrahim, T. M. (2005). Strategi Percepatan Adopsidan Difusi Ino-vasi Pertanian Mendukung Prima Tani. Analisis Kebijakan Pertanian, 3(1), 20–37. Norman, D., et al. (1997). Defining and implementing sustainable agriculture.

Sus-tainable Agriculture Series Paper No. 1. Kansas State University, Kansas, U.S.A:

Kansas State University. Retrieved January 13, 2012, from http://www/kansassus-tainableag.org/Library/ksas1.htm

Partzsch, L. (2011). The legitimacy of biofuel certification. Agriculture and Human

Values, 28, 413–425. doi:10.1007/s10460-009-9235-4

Ross, C. (2010). Public summary report RSPO certification assessment PT Hindoli

scheme smallholders South Sumatra Indonesia. Retrieved March 3, 2012, from

http://www.bsigroup.sg/

Roundtable Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). (2007). Interpretasi Nasional Prinsipdan Kriteria RSPO untuk Produksi MInyak Sawit Berkelanjutan: untuk Petani Kelapa

Sawit Republik Indonesia. Final Document. 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2012,

from http://www.rspo.org/?q=node/887.

Roundtable Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). (2010). Prinsipdan Kriteria RSPO untuk Produksi Minyak Sawit Berkelanjutan: Pedomanuntuk Petani Swadaya di

Bawah Sertifikasi Kelompok. Retrieved February 15, 2012, from http://www.rspo.

org/page/529.

Roundtable Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). (2011). Members by country. Retrieved January 3, 2012, from http://www.rspo.org/countrystat/Australia?q=countrystat Siregar, D. K. (2011). Analisis Perbandingan Pendapatan Usahatani Padi Sawah-dengan Usaha Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Rakyat: Studi Kasus Palu Merbo, Desa

Tanjung Rejo, Kecamatan Percut Sei Tuan, Kabupaten Deli Serdang. Published

Master Thesis, University of Sumatera Utara, Medan Indonesia.

Soekartawi. (2005).Prinsip Dasar Komunikasi Pertanian. Jakarta, Indonesia: Penerbit Universitas Indonesia, UI Press.

van Gelder, J. W. (2004). Greasy palms: European buyers of Indonesian palm oil. London, UK: Friends of Earth.

Vanclay, F., & Lawrence, G. (2007). Smallholder rationality and the adoption of environmentally sound practices: A critique of the assumptions of traditional ag-ricultural extension. European Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension,

1(1), 59–90. doi:10.1080/13892249485300061

Vermeulen, S., & Goad, N. (2006). Towards better practice in smallholder palm

oil production. Natural Resource Issues Series No. 5. London, UK: International

Institute for Environment and Development.

Wakker, E. (2004). Greasy palms: The social and ecological impacts of large-scale

oil palm plantation development in Southeast Asia. Netherlands: Friends of Earth.

Wignyosukarto. (2010). Perkebunan Kelapa Sawitdan Alokasi Air. Retrieved March 3, 2012, from http://budiws.wordpress.com

Wilcove, D. S., & Koh, L. P. (2010). Addressing the threats to biodiversity from oil-palm agriculture. Biodiversity and Conservation, 19, 999–1007. doi:10.1007/ s10531-009-9760-x

World Bank. (2008). World development report 2008. Washington, DC: World Bank. World Growth. (2009). Palm oil–The sustainable oil: A report by world growth.

Retrieved January 14, 2012, from www.worldgrowth.org/assets/files/Palm_Oil.pdf WRM. (2004). Oil palm and soybean: Two paradigmatic deforestation cash crops.