PENSIONS WORLDWIDE

Working Papers on the Reform of Pensions, No. 2, 2008.

The Public Interest and Retirement-Income-Protection: The

Design of Mandated Private Pension Arrangements

The Public Interest and Retirement-Income-Protection: The

Design of Mandated Private Pension Arrangements

Mark Hyde* and John Dixon**

* Mark Hyde is a Reader in Public Policy and Management at the University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth PL4 8AA, United Kingdom. Telephone: +44 01752 233230; email: [email protected]; web:

http://www.zyworld.com/PensionsWorldwide/Cover.htm

** John Dixon is a Professor in Public Policy and Management at the University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth PL4 8AA, United Kingdom. Telephone: +44 01752 233274; email: [email protected]; web:

Preface

The shift from public to non-state administration, inherent in recent pension privatisation reforms, has suggested to several observers that pension policy has, globally, converged around the precepts of the “neoliberal” welfare reform model, marginalising the public interest. We reject this one-dimensional characterisation of privatisation. In particular, we identify the diverse ways in which the architects of a distinctive approach to pensions privatisation have sought to promote and protect the public interest, by imposing statutory obligations, with compliance enforced through appropriate regulatory instruments. This has encompassed several public interest objectives, including the promotion of social solidarity, individual and family responsibility in the context of interrupted earnings, security, transparency and accountability. Where mandated private pension arrangements have been introduced, policy makers have been tightly prescriptive with regard to: coverage (who should be protected?); eligibility (under what circumstances may accumulated assets be withdrawn as benefits?); benefits (what form should the retirement benefits derived from pension schemes take?); finance (how should retirement benefits be paid for?); and governance (how should the activities of those with responsibility for administering pension schemes be regulated?). Building on this discussion, we develop a quantitative assessment of the degree to which the design of mandated private pension arrangements is market orientated. Overall, our analysis of the design of mandated private pension arrangements suggests that the diminution of the public interest that seems to be endorsed by “neoliberalism” is not a universal or unambiguous feature of pension privatisation.

Table of Contents

Preface

1. What is the public interest?...11

2. Why is the public interest important?...12

3. Protecting the public interest: governance approaches...14

3.1 Hierarchical governance mode...14

3.2 Co-governing mode...15

3.3 Self-governing mode...16

4. Protecting the public interest: policy instruments...17

5. Overview of mandated private pension arrangements...19

6. Coverage...21

6.1 Coverage exemption...24

6.2 Voluntary coverage...26

6.3 The self-employed...27

7. Eligibility...27

7.1 Retirement...28

7.2 Early retirement...29

7.3 Deferred retirement...31

7.4 Pre-retirement benefit eligibility...31

8. Benefits...35

8.1 Earnings-related benefits...37

8.2 Accumulated savings...39

8.3 Survivors’ benefits...43

8.4 Disability benefits...45

8.5 Mandatory supplementary benefits...46

8.6 Government subsidies and taxes...46

9. Financing...48

9.1 Contributions...49

9.3 Employer-only contributions...53

9.4 Diverted public pension contributions...53

9.5 Multiple contribution liabilities...53

9.6 Additional voluntary contributions...53

9.7 Income for contribution purposes...54

9.8 Tax deductability...55

9.9 Government subsidies...56

10. Governance...56

10.1 Contribution collection...57

10.2 Asset management...60

10.3 Benefit provision...61

10.4 Regulatory regimes...61

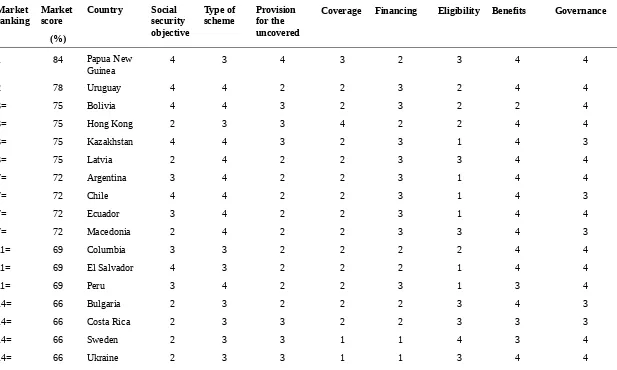

11. Must privatisation be market orientated?...83

11.1 The market orientation of extant mandated private pension schemes...85

12. Conclusion...95

Appendix...100

Acknowledgements...104

The Public Interest and Retirement: The Design of Mandated

Private Pension Arrangements

Mark Hyde and John Dixon

“It is not markets that decide on individual well-being but actors that are collective in their nature” (Trampusch, 2005, p. 3).

The shift from public to non-state administration, inherent in recent pension privatisation reforms, has suggested to several observers that pension policy has converged around the precepts of the neoliberal welfare reform model, marginalising the public interest (Martin, 1993; Klein and Millar, 1995; Ploug, 1995; Bonoli et al., 2000). For Mishra (1990, p. 14), this approach advocates “the return to a pure form of capitalism — the rigour and discipline of the marketplace — including…a lean even if not mean social welfare system, and a reliance on non-government sectors for meeting social needs”. In a similar vein, Martin (1993, p. 6) maintains that the privatisation of welfare, including pensions, has been guided by a global neoliberal alliance of:

However, the belief that pension privatisation has been informed by neoliberalism is not confined to those at the collectivist end of the ideological spectrum. Jose Piñera, the principal architect of Chile’s fully funded defined-contribution pension arrangement, describes how the precepts and principles of neoliberalism “provided our guiding vision”: indeed, the reform “was introduced as part of a coherent set of radical free market reforms”, creating “a political and cultural atmosphere more consistent with free markets and a free society” (Piñera, 2001, pp. 3–4). Indeed, Piñera maintains that Chile‘s so-called “neoliberal” model was subsequently adopted throughout Latin America and by several Central and Eastern European countries. But what about those countries where pension provision has been privatised by governments of the centre-left? This does not, we are told, contradict the contention that privatisation has been informed by neoliberal political economy. The problem with the rhetoric of neoliberalism in its unadulterated form is its apparent endorsement of intensified social inequalities, which creates political barriers to the implementation of market reforms. The solution has been to “seal the victory of the market” by preserving “the placebo of a compassionate public authority”, emphasising “the compatibility of competition with solidarity”. Pensions privatisation is now “carefully surrounded with subsidiary concessions and softer rhetoric” in order to “kill off opposition to neoliberal hegemony completely” (Anderson, 2000, p. 11). In this view, centre-left values are merely an “ideological shell” for neoliberalism, which is now “dominant in the assumptive worlds of policy-makers” (Bonoli et al., 2000, p. 2).

Neoliberalism generally endorses an approach to retirement-income-protection where private interest is predominant. In this conception, private interest has three core dimensions.

interests (people act in their “class interests”), or which discount individual self-interest entirely (people act according to social norms).

Voluntary action. Private interest presumes a voluntary approach to individual decision making, because “every person is the final judge of his own welfare and interests. No economic actor is allowed to have power (economic or otherwise) over other actors” (Swedberg, 2005, p. 30).

Freedom. Individual decision making is legitimate only to the extent that it is consistent with the freedom of others, because “individuals have the right to run their lives as they see fit, provided they do not interfere with the right of others to do the same” (Shapiro, 1998, p. 2). Of particular importance is negative rights (regarding freedom of expression and association, life and property), which impose a duty on the individual to refrain from particular courses of action.

As we suggest below, the public interest is conceptualised as the aggregation of individual interests, and its legitimate scope encompasses the rule of law, to enforce negative rights. Where private interest is predominant, the design and administration of pension arrangements are the object of voluntary action, and, consequently, may be expected to manifest in a variety of ways, reflecting the diverse resource endowments and preferences of consumers and suppliers, constrained only by rules defined by laws of property, tort and contract. Rejected is the notion, admirably expressed by Hutton, that to construct a society “around the nostrum that the public realm is morally, economically and socially inferior to the private realm is to submit to an alien barbarism in which what we hold in common is permanently placed as second best” (Hutton, cited in Marquand, 2004, p. 172). This marginalisation of the public interest has, it is suggested, had serious consequences for society, including diminished trust and social cohesion (Ginn, 2003, 2004).

sought to promote a greater reliance on voluntary third-pillar pension provision, it is largely irrelevant to an understanding of mandated private pension arrangements.

Privatisation generally may be defined as the shifting of a government function, either in whole or in part, from the public to the private sector (Rose, 1989). We are concerned, however, with a specific form of privatisation, where statutory measures have been adopted to give a role to the private (non-state) sector in the administration of mandatory pension arrangements. This form of privatisation has been embraced in Latin America, Central and Eastern Europe, Western Europe and Australasia. What distinguishes this approach, described elsewhere as “forced saving” (Bateman et al., 2001), is its emphasis on statutory compulsion. Specified individuals are required by law to join a private pension plan, operating within the framework of a state-mandated private pension scheme, instead of, or in addition to, participating in a public pension scheme. As we shall see, such privatisation may encompass first- and second-pillar provision. This approach may be distinguished from three alternative approaches to pension privatisation. The first is where the enabling legislation that established public pension schemes exempts from coverage those who are members of an equivalent private pension plan. This is characteristic of countries operating National Provident Funds (Dixon, 1999). The second is where the membership of occupational pension plans is made, by employment law, a condition of employment. The third approach is “privatisation-by-stealth”, where the retrenchment of public provision (for example, by reducing benefits, or by tightening eligibility and coverage criteria) creates a “social protection gap” (Bonoli et al., 2000), which encourages individuals to voluntarily affiliate to a private scheme.

organisations, such as labour unions and community-based associations, and social partner organisations. Thus we are not concerned exclusively with commercial-for-profit provision in a competitive market setting. In sum, the pension privatisation initiatives that comprise the focus of this paper have two broad defining characteristics: mandated compulsory scheme membership and the possibility of a wide compass of non-state scheme administration.

This paper has two central aims. First, we identify the common and distinctive ways that the architects of extant mandated private arrangements have sought to promote and protect the public interest, by imposing statutory obligations, with compliance enforced through appropriate regulatory instruments. This has encompassed, inter alia: social solidarity, or the promotion of social cohesion through inclusiveness and income redistribution; security, by accentuating the sustainability of pension arrangements, both organisationally and financially; individual responsibility, to ensure that retirement income is distributed in accordance with (employment focussed) desert, and to prevent unnecessary welfare dependence; and transparency and accountability, which increase the likelihood that pension institutions will be seen to act in accordance with the requirements of the public interest. We illustrate these and other mandated private pension arrangement attributes with regard to five areas of social security design.

Coverage requirements (who is required to be protected — the covered person — by the scheme?).

Benefit eligibility requirements (under what conditions may accumulated assets be drawn down as benefits?).

Approved benefit provision requirements (what form do benefits take?).

Governance, which is concerned with the nature and degree of intrusiveness of regulatory arrangements to ensure compliance with statutory obligations.

Second, and building on this discussion, we develop a quantitative assessment of the degree to which the design of extant mandated private pension arrangements is market orientated.1 Our discussion demonstrates that public interest concerns have

been integral to this distinctive form of pension privatisation. The diminution of the public interest that seems to be endorsed by neoliberalism is not a universal or unambiguous feature of pensions privatisation.

1. What is the public interest?

Determining how the public interest with regard to pension arrangements differs from the private interests of those who are charged with the responsibility for their administration, and those who are affiliated as active contributors and retirees, is problematic, as, indeed, is deciding what collective actions are justified in the public interest. Public choice theorists argue that the public interest is only knowable as the aggregation of private interests, as revealed in the marketplace (Arrow, 1963). Others, such as communitarians (Sandel, 1982) and idealists (Wolff, 1973), maintain that the public interest is grounded in a notion of the collectivity, or the “common good”, which is different from, and greater than, the sum of any private interests. In this sense, the public interest is constitutive of the individual, partly because the common good reflects shared values and creates social cohesion and identity (Plant, 1991). Involved is a delicate balancing act by government: on one side is private interest (the self-interested autonomy of contributors, retirees, and the range of agents responsible for the administration of pension arrangements), giving rise to the case for the promotion of negative freedom; on the other is the public interest (involving societal control), giving rise to the case for constraining negative freedom so as to promote positive freedom

(Berlin, 1969). Rouseau (1974), who predicted more than two centuries ago that individual self-interest will routinely prevail over the public interest, articulated the long-standing dilemmatic governance challenge: “[How] to devise a form of association which will defend and protect the person and possessions of each associate with all the collective strength, and in which each is united with all, yet obeys only himself and remains as free as before” (1974, p. 17).

2. Why is the public interest important?

Any statutory shift in responsibility for administering pension provision away from the state creates a new governance environment in which the need to protect the public interest, grounded on the premise that the private sphere can do harm to others, justifies state intervention to correct the adverse consequences of private actions (Mill, 1968). Such diswelfares flow from one or more of the risks inherent in the private (non-state) provision of pensions.

Investment risks. The risk that agencies responsible for administering pension schemes will be unable to supply promised or expected retirement benefits, because rates of return are lower than anticipated, due perhaps to exogenous downturn in capital markets, to less-than-optimal portfolio management performance, or even to corporate or management malfeasance. The financial cost of this is carried by retirees under defined-contribution programmes, and by scheme sponsors under defined-benefit programmes.

carried by retirees, if scheme sponsors can legally abdicate from meeting their full contractual obligations.

Longevity risks. The risk that retirees will live longer than can be sustained by accumulated retirement savings. The cost of this is carried by the retirees, if they take their benefits as lump-sums or programmed withdrawals, insurance companies, if retirement benefits are annuitised, or by scheme sponsors under defined-benefit schemes.

Inflation risks. The risk that future price rises with diminish the purchasing power of pension income. The cost of this is carried by retirees if they take their benefits as lump-sums, programmed withdrawals, or non-indexed annuities, or by insurance companies if annuities are indexed.

Consumer choice risks. The risk that those affiliated to pension schemes will make choices that, with the passage of time, become inappropriate to their retirement needs. This may reflect: imperfect information regarding the likely value of retirement benefits, which may be exacerbated by poor advice or advice given in bad faith; and public policy risk, particularly the possibility of changes to state retirement pension provision, state tax regimes and state regulatory policies. The cost is carried by retirees, whose retirement income does not meet their retirement needs.

This all brings into focus the fact that private pension arrangements are designed and administered in an environment in which there are incongruent, even incompatible, public and private motivations. This requires the state to identify the public interest, and how it should protected. Several salient questions are likely to emerge.

What multi-level political and administrative structures and processes are needed to protect the public interest in a market environment?

What are the regulatory structures, processes, and requirements needed to achieve articulated public policy goals in a market environment?

How should sub-optimal provision (for desired public policy outcomes) be dealt with in a market environment?

What public accountability structures, instruments and processes are needed to ensure that agencies responsible for administering pension schemes are publicly accountable for the degree to which they achieve the public policy goals expected of them?

3. Protecting the public interest: governance approaches

In addressing these challenges, the state may choose to adopt one or a combination of three governance modes: hierarchical, co-governing and self-governing. Each entails a separate conceptualisation of the public good and logic of collective action.

3.1 Hierarchical governance mode

decided upon, the state uses force, coercion, manipulation, persuasion or its legitimate authority to achieve its desired policy outcomes.

The state’s adoption of this governance mode would reflect a policy decision to the effect that the statutory transference of responsibility for administering pension schemes away from the public sector does not diminish, let alone displace, its public interest responsibilities. This would be achieved by the state imposing rights and obligations, with compliance supervised and enforced by one or more public regulatory agencies. Regulatory compliance, then, would depend on the ease of regulatory violation detection, the probability of regulatory sanctions being imposed on violators, and the magnitude of those sanctions (see Young, 1992, p. 176). As we shall see, this governance mode predominates in the design and administration of extant mandated private pension arrangements.

3.2 Co-governing governance mode

This requires those with the responsibility for administering private pension schemes to cede some autonomy to the state-endorsed voluntary regulatory network to which they belong, in return for agreed common rights and compliance with common obligations. It is premised on the principle that they should, with government (and perhaps representatives of both contributors and retirees), co-determine, co-protect and co-promote the public interest. In this context, a network is defined as:

By so belonging, all members of the voluntary regulatory network would come to share a commitment to a common set of regulatory values, which presumes that there is a synergy between the categorical interests of all network participants, and which constrains the public interest to an exclusive set of categorical interests (or aggregative common private interests). This has, of course, implications for the state’s role in the articulation of what constitutes the public interest.

The state’s endorsement of this governance mode would reflect a policy decision to the effect that the statutory transference of responsibility for administering pension schemes away from the public sector allows the displacement of its public interest responsibilities to a voluntary regulatory network focused on an exclusive set of categorical interests. Regulation is achieved by state-endorsed voluntary regulation, where regulations are co-designed, co-authorised and co-implemented by an exclusive set of stakeholders. Regulatory compliance would be contingent upon the regulated having a commitment to a common set of regulatory values grounded in a set of categorical interests. This governance mode is a salient feature of a small number of mandated private pension arrangements, particularly those that have been instituted in continental Europe, where there is a strong tradition of stakeholder engagement in the conduct of industrial relations.

3.3 Self-governing governance mode

This requires those with the responsibility for administering private pension schemes to self-regulate their conduct in accordance with the rights and obligations articulated in enforceable contracts, negotiated in context of the statutory market environment. It rests on two premises: the public interest is knowable only as an expression of the “will” of the market — the aggregation of individual preferences as revealed in the marketplace (Arrow, 1963, 1967; Friedman, 1962); and the state is inherently inefficient, ineffective, and, in itself, unable to protect the public interest.

pension schemes away from the public sector relieves it of any public interest responsibilities, beyond determining a set of enforceable market transaction rules embedded in the laws of property, tort and contract. Contractual compliance would be instrumental, based on economic calculations of net compliance costs. Regulation is achieved by the state enforcing contracts embodying a zero tolerance of non-compliance and full restitution as the ultimate sanction. Although elements of self-regulation are evident in extant mandated private pension arrangements, this is not the preferred dominant governance mode.

4. Protecting the public interest: policy instruments

However the state chooses to protect the public interest, it must be cognisant of the implications of its regulatory attitudes and behaviour on the balance of power between itself and those it seeks to regulate, and on the rights of the regulated in a statutory market environment, where there may be incongruent, even incompatible, public- and private-interest goals. In such circumstances, the state must at the very least be willing and able to articulate a set of statutory design features, embracing:

the desired characteristics of the statutory market environment created: viz. who should be obliged to purchase and pay for what type of retirement savings vehicles, for consumption by whom under what future circumstances;

the characteristics of acceptable sellers of retirement savings vehicles: viz. ownership, corporate governance, financial and domicile (the content of structural regulations); and

The enforcement of these statutory design features necessarily entails a mix of regulatory instruments (Gunningham and Grabosky, 1998):

Command and control instruments, which can include: programme design standards (such as required programme coverage, eligibility, finance and benefit provision features); criminal liability (in the event of malfeasance by any contractual party); process standards (such as acceptable forms of corporate behaviour like institutional management practices, investment portfolio management practices, and information management and disclosure practices); and performance standards (such as a benchmark standard for rates of return on contributors’ assets).

Economic instruments, which can include: broad-based economic instruments (such as licensing and registration fees and security bond requirements); government subsidies (to offset any differential cost associated with the coverage of particular target population groups); tax disincentives (such as punitive corporate tax rates being applied if an acceptable rate of return on contributors’ assets is not achieved); and tax incentives (such as preferential corporate tax rates being applied if an acceptable rate of return on contributors’ assets is not achieved); and civil legal liability (such as a right to full restitution in the event of culpable contractual non-performance).

Information instruments, which can include: public education programmes (such as performance league tables); corporate performance reporting (such as mandatory performance indicator disclosure); right-to-know requirements (such as mandatory financial disclosures); and product certification (such as state-approval of particular types of retirement benefit products).

Asymmetrical information flows, where those with the responsibility for administering private pension schemes distort or withhold from regulators the information that is necessary to regulate effectively (say, information regarding financial product commission rates; management incentive and bonus payments; actual administrative costs; actual profit margins; proposed or likely business rationalisation measures; and corporate mergers or takeovers to achieve private-interest ends).

Agency capture, where those with the responsibility for administering private pension schemes manipulate the regulators (by, perhaps, strategic agenda setting or compromise bargaining at the political or administrative levels, to achieve private-interest ends).

Building and maintaining popular trust in mandated private pension arrangements, and, indeed, in government as the trustee of the public interest, suggests that any regulatory mechanism put in place must have the following objectives.

To ensure that both the regulated and the external regulators act co-operatively, working together towards the achievement of mutually beneficial and equitable retirement income outcomes.

To be flexible enough to allow the regulated to respond to the challenges of complexity, diversity and the dynamics of modern society.

To encourage compliance by not imposing excessive obligations on the regulated, whilst discouraging non-compliance by effectively enforcing those obligations that are imposed.

To be transparent, so as to foster co-ordination and co-operation between the community-at-large, the regulated and external regulators.

To ensure that the desired degree of market competition is attained and maintained.

We turn now to the common, as well as the diverse and distinctive, ways that these aims, objectives and policy instruments have been reflected in the design of extant mandated private pension arrangements.

5. Overview of mandated private pension arrangements

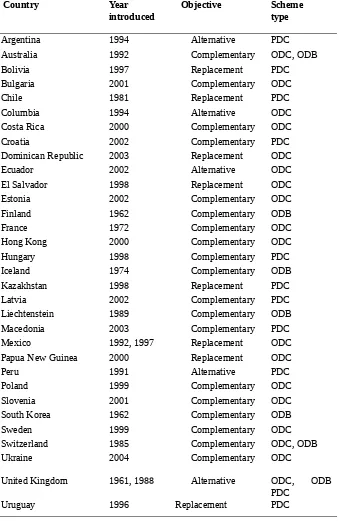

Mandated private pension arrangements have been embraced by countries in four regions — Latin America (11 countries or 34 percent), Central and Eastern Europe (9 countries or 28 percent), Western Europe (7 countries or 22 percent) and Australasia (5 countries or 16 percent). Most were introduced in the 1990s and 2000s (75 percent). Such schemes compliment public provision in a majority of instances (19 countries or 59 percent), although some have replaced public provision (8 countries or 25 percent), while several provide an alternative to public provision (5 countries or 16 percent), whether as an alternative to a public first-pillar pension programme — as in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru (10 percent) — or a public second-pillar pension programme — as in Argentina and the United Kingdom (6 percent).

Mandated private pension schemes coexist with public retirement-benefit provision in all but one country, Papua New Guinea. They most commonly co-exist with public social insurance programmes (25 countries or 78 percent), although such provision is being phased out in five countries (Chile, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Mexico and Uruguay). Interestingly, only in Slovenia, which uses mandated private schemes to finance the early retirement of employees in designated jobs, are retirees required to pay contributions towards their first-pillar social insurance retirement pensions (Slovenia, 1999 Pension and Invalidity Insurance Act, Part XII, Articles 283 [5] and 284 [1]). Mandated private schemes also commonly co-exist with tax-financed social assistance programmes (24 countries or 75 percent).

Argentina and Ecuador have chosen to freeze accumulated entitlements, which can be drawn upon once the qualifying conditions for a public retirement pension have been met.

6. Coverage

Table 1. An overview of mandated private pension arrangements

United Kingdom 1961, 1988 Alternative ODC, ODB

PDC

Uruguay 1996 Replacement PDC

Notation: PDC: Personal Defined-Contribution scheme

charged by sellers (as reflected in voluntary third-pillar pension arrangements, which have embraced the self-governing governance mode) (Simpson, 1996; Murray, 1997), although affiliation may be made mandatory under specific employment contracts, which embeds purchase decisions in choice-of-employment decisions. Under mandated private pension arrangements, however, the degree of coverage is determined by statute, reflecting one or more of a range of public interest concerns, including, inter alia, the appropriate balance between inclusiveness and desert, defined in terms of work participation, the need to expedite privatisation, by ensuring a smooth transition between public and private provision, and the requirement that both the term of affiliation during which contributions are paid, and employee earnings, are sufficient to generate a satisfactory retirement income (Gillion et al., 2000).

coverage by mandating a network of voluntary occupational pension schemes, developed initially under collective bargaining agreements between employer federations and labour unions, which means that membership is usually based on union affiliation. Coverage exclusions are common (29 countries or 91 percent), which has important implications for women. The most restricted coverage may be found in Slovenia, where it is limited to employees “performing particularly hard work and work harmful to health as well as [those] performing professional activities which cannot be successfully performed after attaining a certain age” (Slovenia, 1999 Pension and Invalidity Insurance Act, Part XII, Article 280 [1]). The particular jobs that fall into this category have been designated by the Minister for Labour, with the “consent of the relevant labour union and employer’s association” (Slovenia, 1999 Pension and Invalidity Insurance Act, Part XII, Article 280 [3]).

6.1 Coverage exemption

Coverage exemptions, which are of course also characteristic of publicly administered pension schemes, may be instituted for several reasons (Gillion et al., 2000). In some countries, coverage exclusions are part of a strategy designed to phase in mandated private retirement-benefit schemes. Others have made a strategic decision to exclude particular employee categories. Most commonly, this takes the form of exempting employees in particular sectors and industries (21 countries or 66 percent), particularly public-sector employees (19 countries or 90 percent of cases), all of whom are covered by special schemes, although in six of those countries (32 percent of cases) such arrangements are being phased out (Bolivia, Chile, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Peru and Uruguay). There are, however, five other significant excluded categories of employees.

retirement-pension programmes (Bulgaria, Croatia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Latvia, Poland and Uruguay). They are permitted voluntary affiliation in only four of those countries (Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador and Latvia). This makes mandatory coverage applicable only for those below this designated age.

The second most common exemption category (6 countries or 19 percent) includes low-income employees (Australia, Bolivia, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Uruguay), whose earnings are arguably insufficient to generate a satisfactory retirement income from a long-term savings arrangement. In all but Bolivia, the earnings threshold below which employees are exempted from coverage is set by law, whereas Bolivia ties its earning threshold to the national minimum wage. This makes mandatory coverage applicable only for those whose earnings are above this designated threshold.

covered under its mandated private retirement provision, also remain eligible for a national supplementary pension.

There are other relatively minor coverage exemption categories: casual employees (Liechtenstein, Papua New Guinea and Switzerland); temporary employees (Liechtenstein and Switzerland); employees who are members of exempted equivalent voluntary occupational-pension schemes (Hong Kong and Liechtenstein); contract workers (Hong Kong and Liechtenstein); domestic servants (Hong Kong and Australia); those above a designated income ceiling (Hong Kong and the Dominican Republic); new employees (Hong Kong, for the first 60 days); and guest workers (Hong Kong). Those in exempt employment can in some countries gain voluntarily affiliation.

6.2 Voluntary coverage

To encourage voluntary affiliation, Recognition Bonds are paid in Bolivia, Chile (where they are indexed), the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador; and employee contributions are tax deductible in Chile, Hungary (up to a ceiling of 25 percent of the contributions paid), Latvia, Peru and Poland. In some countries voluntary affiliation involves a freezing of accumulated public retirement-pension entitlements, which are subsequently paid upon attaining eligibility (as in Kazakhstan, Mexico, Papua New Guinea and Uruguay). In others it entails renouncing such entitlements (as in Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Macedonia and Poland), which effectively means that exempt older workers are discouraged from taking up voluntary affiliation.

6.3 The self-employed

This diverse group, ranging from professionals and small-business owners to street hawkers in the informal employment sector, is a targeted population for mandatory coverage in 15 countries (47 percent), although those without employees are exempt in Liechtenstein (MISSOC, 2002), as are those earning below a specified minimum monthly income in Hong Kong and Uruguay, or the minimum wage in the Ukraine. A further nine countries (28 percent) permit voluntary affiliation for the self-employed. Thus, eight countries (25 percent) make no provision in their mandated private schemes for the self-employed. This may reflect several considerations, including the difficulty of accessing those in the informal sector (as in Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Mexico), the possibility of entrepreneurial disincentives (as in Estonia, Kazakhstan, Slovenia and the United Kingdom), and the nature of the mandated private retirement-benefit schemes (as in South Korea).

7. Eligibility

(Littlewood, 1998). Under mandated private pension arrangements, however, eligibility is determined by statute, reflecting one or more of a range of public interest objectives, including the attainment of an appropriate and equitable work-life-balance, whilst ensuring that the contribution period is sufficient to generate a satisfactory retirement income, and the need for flexibility regarding the withdrawal of accumulated assets, to accommodate a range of pre-retirement contingencies (Gillion et al., 2000).

7.1 Retirement

females to retire earlier than males allows husbands and wives to retire at about the same time” (Gillion et al., 2000, p. 340).

The specification of minimum contribution requirements occurs in only 10 countries (31 percent), all of which require the attainment of a minimum contribution period. This requirement is, on average, 25 years, but ranges from five years (Estonia) to 40 years (Finland and Iceland). To qualify for the publicly funded minimum benefit, however, Chile requires 20 years of contributions; the Dominican Republic specifies 25 years of contributions, and requires beneficiaries to be 65 years of age; and Hungary requires 25 years of contributions.

7.2 Early retirement

category II) to finance an early retirement benefit. This is payable eight years earlier than the normal retirement age for workers deemed to be in labour category I (provided they have at least 10 years of service in category I occupations), or three years earlier if they are deemed to be in labour category II (provided they have at least 15 years of service in category II occupations).

7.3 Deferred retirement

A deferment of retirement is permitted in only seven countries (22 percent). The most parsimonious arrangement is that of Liechtenstein, which permits only a one year deferment. Finland permits a deferment to age 70, Iceland to age 72 (for private-sector employees, reduced to 70 years of age for public-sector employees), and the United Kingdom to age 75. Bolivia, Slovenia and Sweden, however, specify no upper age limit. Entitlements are accrued in Sweden (Sweden, Premium Pension Agency, 2003, p. 20), but they are frozen in Slovenia, with the obligation of the employer to pay contributions ceasing upon deferment (Slovenia, 1999 Pension and Invalidity Insurance Act, Part XII, Articles 283 [4] and 284 [1]).

7.4 Pre-retirement benefit eligibility

repayable interest-free loans (only in Papua New Guinea). The principal contingencies are death and disability.

In the event of the death of a covered employee — a mandated pension fund member — some form of survivors’ benefit is mandatory in 30 countries (94 percent), the exceptions being South Korea and Sweden. Under South Korea‘s employer liability system, the retirement-benefit liability ceases with the death of a covered employee. Under Sweden’s defined-contribution system, the balance standing in a deceased person’s individual premium pension account (irrespective of whether death occurs before or after retirement) is distributed as a survivor bonus amongst other “premium pension savers” (Sweden, Government Offices of Sweden, 2001, p. 24; Sweden, Premium Pension Agency, 2003, p. 20). Interim withdrawal benefits in the event of death are permitted in 27 countries (constituting all defined-contribution systems except Sweden’s), and survivors’ pensions are provided in nine countries (constituting all defined-benefit systems, except South Korea‘s, and Papua New Guinea‘s defined-contribution scheme, which requires mandatory group life insurance to provide survivors’ benefits).

be over the age of 45 years, and must have been married for at least five years. Survivors’ pensions are also payable to surviving divorced spouses who have been married to the deceased for at least 10 years and who have been granted life-long financial support upon divorce. Other surviving spouses qualify for a lump-sum benefit.

The survivors’ benefits paid under mandated defined-benefit schemes are paid to the surviving spouse and children (as in Finland, Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland), to legal heirs (as in Australia), to any nominated individual (as in the United Kingdom), other dependent relatives (as in Liechtenstein), to de facto spouses (as in Iceland) or to divorced spouses (as in Iceland). In Finland, survivors’ pensions are paid to surviving spouses who were married prior to their fiftieth birthday, and, if childless, have been married for five years and are at least 50 years of age (or a disabled pensioner for at least three years), with eligibility ceasing upon remarriage; and to legal, adopted and supported children under 18 years of age. In Iceland, for survivors to qualify for survivors’ pensions, the deceased must have contributed for at least 24 of the 36 months prior to death, and the surviving spouse must be a man or woman who was married to the deceased or who lived in recognised cohabitation or a consensual union with that person for at least two years, without interruption, during which time they must have produced a common issue, or the woman must be pregnant. In all instances, eligibility ceases upon remarriage. Children under the age of 18 qualify for an orphans’ benefit.

In the event of the disabling of a covered employee, some form of disability benefit is mandatory in 20 countries (63 percent). Withdrawal rights are provided for in the 17 countries with mandated defined-contribution schemes (61 percent of cases, the exceptions being Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Estonia, France, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Mexico, Sweden and the United Kingdom), and/or disability pensions are provided in five countries (countries with defined-benefit schemes, except South Korea and the United Kingdom).

53 percent of cases), and thus to be unable to perform any work (Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Papua New Guinea, the Ukraine and Uruguay), to be unable to perform usual work (Australia, Hong Kong and Poland) or to experience a substantial earnings loss (Croatia). A further eight countries (47 percent of cases) provide for partial incapacity, expressed as either a designated degree of earnings loss (63 percent of cases: Argentina, Hungary, Macedonia, Peru and Slovenia), with an averages earning loss of 68 percent, ranging from 50 (Slovenia) to 100 percent (Macedonia); or a designated degree of disability (Chile, Dominican Republic and Switzerland, 38 percent), which averages 59 percent, ranging from 50 (Switzerland) to 66.7 percent (Chile). Only El Salvador requires the purchase of mandatory group disability insurance in lieu of disability withdrawal rights. This provides an annuity to certified disabled covered employees who were actively contributing prior to the onset of disability, with six months’ contributions in the 12 months before the disability was acquired, or with 10 years’ contributions, including three years in the five years before the disability.

To qualify for disability benefits under mandated defined-benefit schemes, disabled covered employees have to demonstrate a designated minimum percentage earnings loss, averaging 53 percent (as in Finland, Iceland, and Liechtenstein), a designated minimum degree of disability (as in Switzerland, where the minimum degree of disability is 50 percent), or total incapacity that precludes them from engaging in their usual work (as in Australia).

Other contingencies justifying interim withdrawals include: permanent emigration (Hong Kong, Papua New Guinea, Switzerland and the Ukraine); the purchase of a home (Papua New Guinea, South Korea and Switzerland); retirement to undertake caring responsibilities (Australia and Chile); the purchase of medical care (Australia and Papua New Guinea); the purchase of group health insurance (Bolivia for retirees and Slovenia for early retirees); the purchase of life insurance (providing survivors’ benefits for a maximum of five years) (Sweden) (Sweden, Premium Pension Agency, 2003, pp. 19–20); retirement on health grounds, subject to a 20-year contribution record (Chile); marriage (Mexico, a withdrawal of one month’s salary is permitted); the purchase of educational services (Papua New Guinea); the onset of financial hardship (Australia); the commencement of self-employment (Switzerland, unless the member’s spouse disagrees, in which case the accrued amount must be transferred to an irrevocable account with a bank or insurance company); the purchase of funeral services (Bolivia); and small inactive individual accounts (Hong Kong, after one year without a contribution credit). Australia has adopted a very distinctive approach to interim withdrawals, where accumulated savings may be run down to cover the cost of treating members or their dependants who are suffering a life threatening illness or injury, or are experiencing acute or chronic mental health problems (including the costs of medical transportation, palliative care and medically necessary modifications to the family home or vehicle), provided such treatment is not readily available through the public health system. Partial withdrawals on an annual basis can also occur in the case of financial hardship being experienced by federal income support beneficiaries who have been in receipt of a pension or benefit for at least 26 weeks, or in order to prevent foreclosure of a mortgage on, or the forced sale of, a member’s principal residence.

8. Benefits

matter involving consumers and suppliers, reflecting their respective preferences (Simpson, 1996; Littlewood, 1998). Under mandated private pension arrangements, however, benefit modalities are determined by statute, reflecting one or more of a range of public interest objectives, including benefit financing sustainability, income adequacy and security, inter-generational justice, the primary importance of family and individual responsibility in the context of interrupted earnings, and the minimisation of welfare dependency (Gillion et al., 2000).

payable to orphans up to age 21 (25 if a student and no age limit if disabled). In the event of covered employees becoming at least two-thirds incapacitated, then from age 60 they qualify for their full retirement pension entitlement.

8.1 Earnings-related benefits

wages, or both. In the United Kingdom, the retirement pension entitlement accrual rate is at least 1/80 of covered annual earnings (defined as 90 percent of earnings upon which social insurance contributions are paid, which is subject to both a minimum and a maximum ceiling), averaged over three years, up to a maximum of 40 years, with pension entitlements accruing from employment since April 1997 being revalued annually at the rate of inflation or 5 percent (cumulative), whichever is the lower. Those who leave pensionable private-sector employment before pensionable age must similarly have their pension entitlements preserved and revalued annually at the rate of inflation or 5 percent (cumulative), whichever is the lower, with those leaving public-sector employment being subject to slightly different rules. The pension must be payable for life and must be based on the product of average or final salary and length of pensionable service. Furthermore, a pension must constitute no less than 75 percent of the retirement-benefit entitlement, for only 25 percent can be paid as a tax-free lump sum. Pensions must be indexed in line with inflation, the cost of which is shared by the pension funds and the government. That part of a pension entitlement accrued since April 1997 must be indexed in line with inflation, up to a maximum of five percent a year calculated on a year-by-year basis, although more generous discretionary pension indexation is permitted. That part of total rights relating to contracting-out before 1997 — the guaranteed minimum pensions accruing between 1988 and 1997 — must be indexed in line with inflation, but only up to a maximum of three percent a year. For guaranteed minimum pensions accruing between 1978 and 1988, the government pays full indexation through the state pension. In South Korea, distinctively, retiring eligible covered employees receive from their employer a lump-sum retirement allowance equal to 30 days’ average wage during the three months preceding the calculation of the annual retirement allowance liability for each year of employment. Employers are, however, not constrained as to the method of payment, which can include cash or in-kind compensation, such as marketable or non-marketable securities (World Bank, 2000, p. 16).

6.0 percent a year, depending on the year of the beneficiary’s birth); France (where they are actuarially reduced); Iceland (where they are also actuarially reduced); and the United Kingdom (where they may be actuarially reduced, depending on the personnel needs of sponsoring employers, although the accumulated “protected rights” component, comprising the age-related social insurance contribution rebate and, with respect only to personal-pension schemes, the tax relief on the employee’s contributions, must be used to purchase an annuity, on a unisex basis, to provide a pension between the ages of 60 and 65 years). Gradual retirement benefits are also provided in Finland (equal to 50 percent of the difference between previous full-time earnings and earnings from part-time employment) and France (where the pension and income from employment may not exceed the salary received prior to retirement).

Deferment bonuses are paid under mandated defined-benefit schemes in both Finland (1 percent for each deferred month, until the pension right accrual reaches 60 percent of the highest pensionable earnings) and Iceland (which provides for actuarially determined pension entitlement increases).

8.2 Accumulated savings

The benefit entitlements derived from mandated private pension schemes are, predominantly, financed from accumulated deferred earnings, plus interest income, reflecting the widespread acceptance of the public interest concern that retirement should be sustainable, over the long-term. Retirement benefit entitlements may be accessed in a variety of ways: a withdrawal to purchase annuities (26 countries or 93 percent of cases, but mandatory only in 7 countries); periodic programmed withdrawals (18 countries or 64 percent of cases, but mandatory only in Bulgaria); a lump sum withdrawal (as in 18 countries or 64 percent of cases, but mandatory only in Hong Kong and Kazakhstan); or some combination of these (18 countries or 64 percent of cases).

value of the annuitant’s pension capital distributed amongst the chosen pension funds (Sweden, Government Offices of Sweden, 2001, p. 33). In Switzerland, annuities are subject to a minimum annuity requirement. This is achieved by the specification of an annuitisation divisor, currently set at 7.2. In Estonia, interestingly, a guaranteed disbursement period of at least five years must be specified in all annuity contracts, which requires the continued payment of the contracted annuity benefit to a nominated beneficiary for that period (Estonia, 2001 Funded Pensions Act, Sections 23 [1] and 150). In the United Kingdom, an annuity must be purchased with at least 75 percent of accumulated savings, including the “protected rights” component, with the balance payable as a tax-free lump sum. That part of an annuity purchased with “protected rights” funds accrued since 1997 must be indexed in line with inflation, subject to a cap of 5 percent a year, while that part purchased with savings accrued between April 1988 and April 1997 must be subject to an inflation indexation cap of 3 percent a year.

lump-sum withdrawal can only be made from the assets remaining after the purchase of an annuity that is equal to 70 percent of pensionable salary. In Mexico, such a withdrawal can be made only if the accrued savings exceed 130 percent of the amount required to purchase an annuity equal to the minimum pension guarantee (Grandolini and Cerda, 1998, p. 13).

defined-contribution schemes. The “protected rights” component under personal defined-contribution schemes (comprising the age-related social insurance contribution rebate and the tax relief on the employee’s contributions) must be included in the periodic withdrawal benefits in the event of the deferral of an annuity purchase. Argentina permits retirees who initially opt for programmed withdrawals to purchase, at a later stage, an annuity from their remaining accumulated savings (Vittas, 1997, p. 13)

8.3 Survivors’ benefits

survivors’ programmed withdrawal benefits with survivor annuities provided under a mandatory group life insurance policy. Croatia and Macedonia have adopted a quite different approach. The accumulated savings standing in a member’s account must upon death be transferred to the public agency responsible for administering first-pillar death benefits. The amount transferred determines the survivors’ and disability benefit entitlement (Macedonia, 2001 Law on Mandatory Fully Funded Pension Insurance, Article G9 [1]).

United Kingdom the survivors’ pension is 50 percent of the member’s pension entitlement at the time of death.

8.4 Disability benefits

Provision for disability is widespread, reflecting at least two public interest concerns: the importance of individual responsibility, which manifests here as self-provisioning in the context of interrupted earnings; and the minimisation of dependence on statutory social assistance (Gillion et al., 2000). Benefits to disabled covered employees are provided under defined-contribution schemes in three ways. Most countries (94 percent) permit eligible disabled covered employees to withdraw the balance standing in their account at the onset of disability, which must be used to finance disability annuities in the Dominican Republic and Uruguay. In France, covered employees who become at least two-thirds incapacitated qualify for their full retirement pension entitlement from the age of 60. In the Dominican Republic, interestingly, certified disabled covered workers are required to purchase an annuity equal to 60 percent of their average indexed wage during three years prior to the onset of total disability, or 30 percent in the event of partial disability, with the annuity provider being obliged to make up the difference between the amount accumulated in the individual account and the amount required for the purchase of the prescribed annuity. Croatia and Macedonia require that the accumulated savings standing in a member’s account must, in the event of non-occupational disability, be transferred to the agency responsible for administering first-pillar disability benefits, which determines the benefit entitlement (Macedonia, 2001 Law on Mandatory Fully Funded Pension Insurance, Article G8 [1]).

for at least six months of the previous 12 months. In Finland, the full disability pension is equivalent to the projected accrued retirement pension entitlement to age 65 at the time of the disability. This projection must be made on the following basis: 1.5 percent of average pensionable earnings until the age of 50; 1.2 percent between the ages of 50 and 60; and 0.08 percent between the ages of ages 60 and 65. The projected entitlement is subject to a maximum limit equal to 60 percent of pensionable earnings, with the accrued pension entitlement being indexed in line with cost of living and average wages, weighted equally. The partial disability pension entitlement is equal to 50 percent of the full pension. In Switzerland, the disability pension entitlement equates to accumulated savings plus contributions, but without any accruing interest, projected on the basis of one year’s final pre-disability wage for every 7.2 years remaining before reaching retirement age. This can be commuted to a lump sum if the entitlements are small. Also payable is a child’s allowance for each eligible dependent child equal to 20 percent of accrued full disability pension entitlement.

8.5 Mandatory supplementary benefits

The provision of supplementary benefits is mandatory in only two countries, the cost of which is deducted from members’ individual accounts. In Bolivia, survivors of deceased retirees receive a flat-rate funeral expenses benefit, and retirees receive health benefits, under pension-fund sponsored group health insurance. In Slovenia, early retirees receive similar health benefits (Slovenia, 1999 Pension and Invalidity Insurance Act, Part XII, Articles 283 [5] and 284 [1]).

8.6 Government subsidies and taxes

Public subsidies for mandated private pension schemes are widespread, reflecting several public interest concerns. Most commonly, they seek to maintain acceptable minimum benefits2 (11 countries or 61 percent of cases), typically a

2 The provision of government supplementation has implications for (1) the public interest goal of

minimum benefit guarantee (as in Argentina, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Hungary, Mexico, and Poland). In Chile, only beneficiaries with a 20-year or more contribution record receive the state-funded minimum pension guarantee. In the Dominican Republic, the maximum pension guarantee is 70 percent of the private-sector minimum wage, financed by a levy equal to 0.4 percent of the contributions collected (Palacios, 2003, p. 32), although retired self-employed workers receive the same minimum benefit funded by government when they reach 65, provided they have a 25-year or more contribution record. In Hungary, the minimum state pension guarantee, equivalent to 25 percent of their state pension, is provided through the Guarantee Fund, to those who have a 15-year or more contribution record. In Kazakhstan, the minimum retirement income guarantee level is determined annually as part of the national budget process, and has been set at roughly 70 percent of an indexed poverty line (Andrews, 2000, pp. 13–14; World Bank, 1998). In Mexico, the minimum pension guarantee is based on the minimum wage in Mexico City in 1997, indexed to the cost of living (Grandolini and Cerda, 1998, p. 22). South Korea has adopted the novel approach of diverting part of its public lump-sum employment termination benefit to subsidise lump-sum retirement benefits. Where the state previously paid a termination benefit equal to 8.3 percent of wages for up to eight years of service, it has reduced its termination benefits and diverted an amount equal to 1.5 percent of wages to augment retirement benefits (Pensions International, 2000, pp. 1–2).

use their social assistance programmes to support low-income beneficiaries, as do a further 11 countries (Australia, Estonia, Hong Kong, Kazakhstan, Liechtenstein, Macedonia, Slovenia, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland and Uruguay).

Other forms of government support include the augmentation of special reserves in the event of bankruptcy (28 percent of cases: Costa Rica, Croatia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador and Poland); and the subsidisation of administrative and fund management costs (17 percent: Kazakhstan, Latvia — only for a start-up period of 18 months — and Bolivia — from revenue gained from the sale of state enterprises) (Palacios, 2003, p. 22).

Retirement benefits are known to be taxable in 19 countries (58 percent). Only Australia is known to impose a higher tax liability on lump-sum benefits. The Reasonable Benefit Level sets this tax threshold — the maximum benefit that a person can receive over a lifetime, beyond which the highest marginal tax rate applies — which is doubled if at least half the benefit paid is taken as an annuity.

9. Financing

This is concerned with determining which agents should be responsible for financing retirement benefits, and the specific ways that their contributions are utilised to achieve this end. Where the design and administration of pension arrangements are framed primarily in terms of private interest, this is a contractual matter involving consumers, perhaps their employers, and suppliers (Murray, 1997; Booth, 1998). Although redistributive mechanisms may be instituted on a voluntary basis (as in employer sponsored schemes, for example), the salience of individual self-interest is likely to accentuate personal responsibility. Under mandated private pension arrangements, however, benefit financing arrangements are determined by statute, reflecting one or more of a range of public interest objectives, including, inter alia, the sustainability of retirement benefit financing and social solidarity (Gillion et al., 2000).

and France and South Korea, which operate PAYG-financed systems. Each of these countries has adopted quite distinctive approaches. In Finland, 70 percent of the pension liabilities are financed on a PAYG basis, through a pooling mechanism administered by the Central Pension Security Institute, while the remaining 30 percent are pre-funded. In France, benefits are financed on a PAYG basis, in accordance with the principle of inter-generational risk sharing. The pooling mechanism is administered by private not-for-profit central associations of the social partners, and is financed by a 20 percent surcharge (adjusted annually) imposed upon the total contribution collected on incomes between one and four times the designated income ceiling. This means that the only pension assets available for investment are derived from any surplus achieved, when the contributions collected exceed the benefits paid. Under South Korea‘s approach, employers must provide retirement-cum-severance benefits, which are not required to be registered in corporate accounts, although if they are, then up to 50 percent of the accrued benefit liability becomes tax deductible. Employers are obliged to purchase insurance to cover these contingent liabilities, although if they do so, the remaining registered accrued benefit liability becomes tax deductible (World Bank, 2000).

9.1 Contributions

financed entirely from employer contributions. Employee only contributions are imposed in a substantial minority of countries (53 percent, or 17 countries) where mandated private pension arrangements have been introduced. A majority of mandated private schemes, then, entail a degree of vertical income redistribution, rather than an exclusive focus on individual responsibility, which is, of course, the emphasis of the neoliberal reform model.

exempts them from having to provide access to a stakeholder pension. Employers may otherwise contribute whatever they choose up to the annual income ceiling applicable to employees.

Statutory incidence. Generally, the statutory incidence of the total contribution rate is unequal, with the employer paying, on average, a larger share (65.7 percent) than the employee (34.3 percent). Indeed, it is equal only in Hong Kong, Liechtenstein and Switzerland. The largest employer statutory incidence is in Bulgaria (80 percent). In Hong Kong, employers alone are required to pay contributions with respect to low-income employees, including casual employees.

9.2 Employee-only contributions

These are rather less common (13 countries or 41 percent), and are concentrated in Latin America (50 percent of cases: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Uruguay) and Central and Eastern Europe (33 percent of cases: Croatia, Hungary, Latvia, Macedonia and Poland), with the remaining countries being the United Kingdom (for those who contract out of the public second-pillar programme to personal pensions plans) and Kazakhstan. The average employee-only contribution rate, where it is specified, is 7.6 percent of earnings, ranging from 2 percent in Latvia (increasing gradually over a ten-year transition period to 10 percent) (Kirsons, 2002) to 10 percent in Argentina (including administration fees), Bolivia, Chile (employees working under arduous conditions receive a supplementary employer contribution of two percent), Kazakhstan and Uruguay. In Uruguay, the statutory contribution rate of 15 percent applies only to designated earnings. For those voluntarily affiliating with monthly earnings that are less than the covered earnings threshold, the contribution rate is reduced to 7.5 percent. In Bolivia, employers are required to deduct and transfer employee-only contributions to an employee’s nominated mandated private pension fund.

9.3 Employer-only contributions

Australia and Slovenia (the contribution rate in Australia is 9 percent, and in Slovenia it is between 2.63 and 4.2 percent [depending on the industry]), averaging 6.2 percent.

9.4 Diverted public pension contributions

Three countries have opted to divert part of their public pension contribution revenue to finance mandated private retirement benefits. Macedonia diverts 35 percent of its total pension contribution, or 7 percent of earnings. Estonia diverts 25 percent of its covered employer’s first-pillar pension contribution, or 4 percent of earnings, which is supplemented by an additional imposition of a 2 percent employee contribution. Sweden assigns 13.5 percent of its total first-pillar pension contribution, or 2.5 percent of earnings.

9.5 Multiple contribution liabilities

Individuals with more than one job who are employed by more than one covered employer universally generate multiple contribution liabilities for themselves and/or their employers. The self-employed, where they are required to, or may voluntarily contribute to, mandated private pension funds (24 countries or 75 percent), are generally required to pay the combined employer and employee contribution rates (21 countries or 88 percent of cases), although a lesser proportion is payable in Sweden (58 percent), Hong Kong (50 percent) and, particularly, the Dominican Republic (29 percent). The average contribution rate is 8.5 percent.

9.6 Additional voluntary contributions

contributions (Australia, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, Mexico, Switzerland and the United Kingdom). A further seven countries (22 percent) permit additional voluntary contributions to be paid by the self-employed as either regular fixed amounts (Argentina and El Salvador) or ad hoc amounts (Australia, Bolivia, Chile, Hungary and Iceland). In Australia, employees can negotiate additional voluntary contributions — so-called “salary sacrifices” — from their employer, which are withheld from their pre-tax salary, and which are tax deductible for employers. Employees may also pay additional voluntary contributions — so-called “un-deducted contributions” — into either the state-mandated pension fund to which their employer already contributes or a “superannuation plan” — a personal pension plan operated by a state-mandated open or retail pension fund. The benefits derived from this are not taxable, although investment earnings are. Iceland limits the tax deductibility of additional voluntary contributions by employees to no more than 3 percent of salary. In Hong Kong, this limit is 10 percent of salary.

9.7 Income for contribution purposes