Long-term breastfeeding; changing attitudes and

overcoming challenges

Karleen D Gribble PhD

The experiences of 107 Australian women who were breastfeeding a child two years or older were gathered via a written questionnaire with open-ended questions. Eighty-seven percent of women had not originally intended to breastfeed long-term and many had initially felt disgust for breastfeeding beyond infancy. Mothers changed their opinion about long-long-term breastfeeding as they saw their child enjoy breastfeeding, as their knowledge about breastfeeding increased and as they were exposed to long-term breastfeeding role models. It was common for mothers to be shocked the first time they saw a non-infant breastfeed but this exposure was also a part of the process by which they came to consider continuing to breastfeed themselves. Women often found long-term breastfeeding role models as well as information and moral support for breastfeeding continuance within a peer breastfeeding support organisation (the Australian Breastfeeding Association). Previous breastfeeding experiences had assisted women in their current breastfeeding relationship. Mothers had overcome many challenges in order to continue breastfeeding and breastfeeding was sometimes discontinuous, with children weaning from days to years before resuming breastfeeding. This study suggests that postnatal interventions may be successful in increasing breastfeeding duration. Such interventions might include: continuing provision of breastfeeding information throughout the lactation period, facilitation of exposure to long-term breastfeeding, and referral to peer breastfeeding support organisations.

Keywords: extended breastfeeding, peer breastfeeding support, weaning

Breastfeeding Review 2008; 16 (1): 5–15

Introduction

It is widely understood that breastfeeding is important to the well-being of young babies. However, research indicates that breastfeeding underpins the normal health, growth and development of not just infants but also young children. Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF recommend

that babies be exclusively breastfed for their first six months

of life and that breastfeeding continue with the addition of complementary foods for up to two years or more (World Health Organization & UNICEF 2003). Breastfeeding assists children to

fight infection via immunological components that are present

in breastmilk, the concentrations of which remain stable from six months to beyond the second year of lactation (Goldman, Goldblum & Garza 1983). Breastfeeding provides breastfed children with immunological factors that would otherwise be unavailable to them. In some contexts, two and three year old children who have been weaned have higher morbidity and mortality rates than children of the same age who continue to be breastfed (Briend & Bari 1989; Feachem & Koblinsky 1984; Lepage, Munyakazi & Hennart 1981; Molbak et al 1994; WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality 2000; World Health Organization 1998). Breastfeeding supplies a self-regulated intake of food (Dewey 2003) that contains the balance of nutrients needed for normal brain development and physical growth (WHO

Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group 2006). Breastfeeding also provides hormonal and physical stimuli that facilitate maternal caregiving (Fergusson & Woodward 1999; Gribble 2006; Lavelli & Poli 1998). Some research has found that early weaning from breastfeeding is associated with poorer performance in cognitive tests (Anderson, Johnstone & Remley 1999), a greater risk of obesity (Harder, Schellong & Plagemann 2006; von Kries et al 1999; WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group 2006)

and a greater risk of emotional and behavioural difficulties in

children (Fergusson, Horwood & Shannon 1987; Oddy 2006). The health of mothers is also affected by breastfeeding. Breast cancer risk decreases with increased lifetime duration of breastfeeding (Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer 2002; Zheng et al 2000) and the risk is reduced by as much as 0% in women who have breastfed each of their children for two years or more (Zheng et al 2000). Women who breastfeed each of their children for more than one year decrease their risk of hip fracture by two thirds (Cumming & Klineberg 1993; Huo, Lauderdale & Li 2003) and breastfeeding also decreases the incidence of maternal type 2 diabetes (Stuebe et al 200), rheumatoid arthritis (Karlson et al 2004), ovarian cancer (Tung et al 200) and heart attack (Stuebe et al 2006).

Despite official health recommendations, the deleterious

effects of early weaning on children and the positive impact of breastfeeding on maternal health, premature weaning remains a

serious problem in every western nation including Australia, the US, the UK, Norway and Canada (Callen & Pinelli 2004; Lande et al 2004). In Australia, breastfeeding initiation rates approach 90% (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2003). However, less than a quarter of children are breastfeeding at 12 months and by the time children are two years of age only 1% are breastfed (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2003). The small fraction of women who have

breastfed their children for two years or more could be defined

as the ‘successful’ breastfeeders because they have continued to

breastfeed for the duration recommended by WHO/UNICEF 1.

If it can be understood how and why some women are able to avoid premature weaning this may provide information that will increase the success of interventions to support breastfeeding continuance. As a part of a larger study examining breastfeeding beyond infancy, the experiences of Australian mothers who had breastfed their children for two years or more were considered and the process by which they came to practice long-term breastfeeding was explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A convenience sample of mothers was recruited via advertisement and word of mouth. To be eligible to participate, mothers were required to be living in Australia and breastfeeding a child two years of age or older. The Australian Breastfeeding Association (ABA) gave permission for participant recruitment requests to be posted on their email lists and Internet bulletin boards and the request for study participants was also spread within their Australia-wide network of breastfeeding support groups. The distribution of information about the study to anyone who might qualify as a participant was encouraged and, as a result, descriptions of the study were posted on a number of other Internet sites and information about the study was disseminated outside of the ABA network. Mothers who responded to advertisements were sent a letter outlining the method, background and purpose of the study. Those who wished to participate were directed to request a copy of the study questionnaire; the request of which was considered as providing informed consent. Questionnaires were delivered via email, post and in person. There was a 97% response rate. Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Western Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee.

Data for this study was generated through completion of a

written questionnaire. In order to confirm validity, a pilot was

tested with ten women who had breastfed a child for two years or more. Their feedback regarding clarity and content was taken

into account before finalization of the study instrument. Study

participants were asked to recount the history of their current breastfeeding relationship. They were also asked to describe their initial breastfeeding intentions and, if these intentions had changed over time, how and why they had changed. Mothers were also asked to describe the impact that any previous breastfeeding experience had had on their current breastfeeding relationship.

Questionnaire responses were analysed and emergent coding used to reveal recurring themes. The reliability of coding was tested by providing the coding categories and a random 20% sample of the responses to each question to two coders. The percentage of agreement between these coders provided an overall inter-rater reliability of 94.9%. Quantitative analyses were carried out using Statistica (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK). The relationship between birth order and breastfeeding duration of all of the children of study participants was investigated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test was used to assess whether the survival

curves were significantly different from one another.

RESULTS

One hundred and seven women participated in this study. Mothers ranged in age from 21 to 4 years and had from one to

1 The use of the descriptor ‘successful’ is not meant to imply that women who have

not breastfed for two years or more have failed at breastfeeding; however, it may mean that they have been failed by a society that has not enabled them to breastfeed.

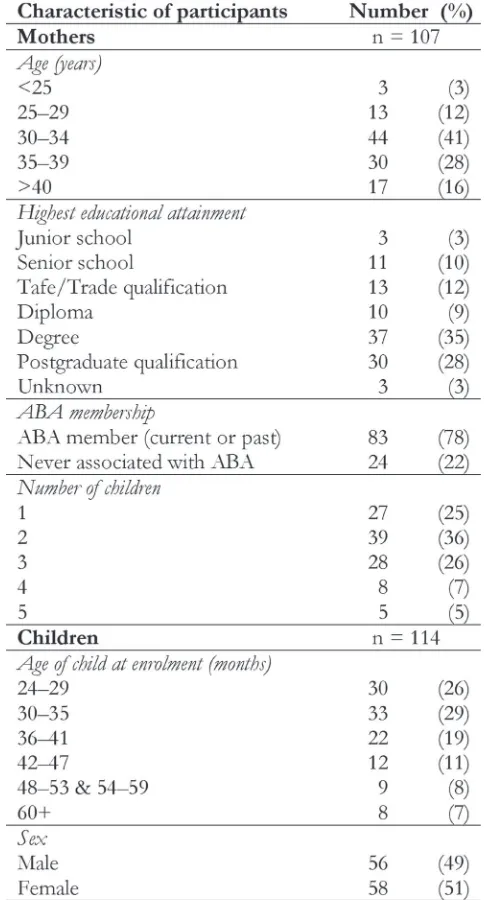

five children. At the time they completed the study questionnaire,

84 mothers were breastfeeding one child, 22 mothers were breastfeeding two children simultaneously and one mother was breastfeeding three children simultaneously. Seven women were breastfeeding two children two years or older simultaneously and completed a questionnaire for each child. The study population was highly educated, 63% held at least an undergraduate university degree. Seventy-eight percent of participants were current or past members of ABA and 22% of participants had never been members. The children who were subjects in this study ranged in age from 24 to 96 months. A summary of the demographic and personal characteristics of participants is shown in Table 1.

Breastfeeding intentions

Participants were asked whether they had intended to breastfeed a child as old as their current long-term breastfeeding child when

they first started breastfeeding. Twelve women (11%) stated that

they hadn’t had a breastfeeding duration goal when they initiated

breastfeeding with their first child. A further 81 women (76%)

stated that they had not intended to breastfeed a child as old

as the subject child when they first started breastfeeding and mothers breastfeeding their first child were equally as likely as

mothers breastfeeding subsequent children to assert this. Many of these women stated that they had thought that they would only breastfeed for a short time:

I made a very public statement that I would only feed for 4 months, after that I wanted my boobs back.

(Joy 2, breastfeeding a daughter, 2 months)

I was planning to feed for 6 months only as I thought that was how you did it.

(Alanna, breastfeeding a daughter, 36 months)

Some women expressed that they had originally felt disgust for the practice of breastfeeding beyond infancy:

I found the idea of feeding older children gross and tasteless and a bit off. I thought it was mothers forcing their children to remain dependent babies.

(Barbara, breastfeeding a son, 33months)

I must admit that I used to think that it was a bit sick to see someone breastfeed a child who could walk and talk and ask for breastmilk.

(Nicole, breastfeeding a daughter, 31 months)

Those women who did not have a breastfeeding duration

goal and those whose breastfeeding practice did not reflect their

original intention were asked to explain how they came to continue breastfeeding for as long as they had. The most common factor nominated as involved in delaying weaning was that the child enjoyed breastfeeding and did not want to wean:

She always loved feeding… and she was very determined to keep feeding.

(Jocelyn, breastfeeding a daughter, 30 months)

It is because [she] loves the breast so much, that I am still breastfeeding.

(Ariel, breastfeeding a daughter, 34 months)

I think as time went on and she was still feeding and I saw how much she loved it I just accepted the fact that we were in for the long haul.

(Jane, breastfeeding a daughter, 44 months)

Mothers also commonly stated that they had sought or been provided with information about breastfeeding and that the

increased knowledge that had flowed from this information

had contributed to their decision to continue breastfeeding.

Knowledge that influenced their breastfeeding intentions

included the value of breastfeeding to their child and themselves, the normalcy of continuing to breastfeed beyond infancy and

official recommendations about breastfeeding duration:

I began to research breastfeeding and learnt how important it is for many areas of a child’s development. Also, reading about breastfeeding around the world and the WHO recommendations really opened my eyes to the importance of breastfeeding and that it wasn’t unusual to breastfeed beyond infancy.

(Georgia, breastfeeding a daughter, 28 months)

Once [my daughter] was a year old I started getting serious pressure from all around to wean her…I went on the Internet for some help. I…spent hours and days reading all

the sites I could find… I found the Australian Breastfeeding

Association site and became a member and have not looked back.

(Carolyn, breastfeeding a daughter, 36 months)

As in the previous example, membership of ABA was often mentioned by women as part of the reason why they had continued breastfeeding. Furthermore, it was often via ABA

that mothers first saw a non-infant being breastfed. For some

women, this initial exposure to long-term breastfeeding was more surprising than shocking and they embraced the idea of continuing to breastfeed:

at 10 months old we joined the Australian Breastfeeding Association to meet other mums who were still breastfeeding and that’s when I realized we could continue on and on…It was a combination of receiving information and support [there]… that is the reason we are still breastfeeding today.

(Susan, breastfeeding a son, 38 months)

However, many women described how extremely confronting

it was to see a non-infant breastfeeding for the first time:

When my eldest child was 3 months old I went to [an ABA] meeting and the counsellor who was leading the meeting had a daughter who had just turned 3 and was still breastfed. The daughter [jumped] onto her mums lap, lifting up her mums shirt, having a quick drink and then [hopped] off again. I was appalled. This image stuck in my mind and it took me a while to realize that I had never seen a child that

age breastfeed before which was why I was so horrified.

(Sophie, breastfeeding a son, 37 months)

In spite of this initial shock, the experience of seeing non-infants breastfeed also became part of the process by which many mothers decided to continue breastfeeding themselves:

When [my daughter] was about 4 months old I started attending [ABA] meetings and quickly became exposed to mothers feeding older children. I found this a bit strange at the time…but over time and as my own child kept getting older, and kept feeding this exposure to extended breastfeeding kept working away on my attitudes.

(Ellen, breastfeeding a daughter, 36 months)

Once mothers had made a decision to keep breastfeeding, membership of ABA supported them in continuing:

Being a member of ABA has given me the knowledge to defend my decision to continue feeding and the support network of others who have fed/are feeding an ‘older’ baby. It doesn’t seem strange to me because there are so many mums I know now who are feeding children of my children’s ages.

(Georgie, breastfeeding a son, 36 months)

Multiple factors often interacted in mothers’ decision-making concerning breastfeeding continuance. For example, one mother described how her thoughts on how long she would breastfeed for changed as her child continued to enjoy breastfeeding, as her knowledge about breastfeeding grew, as she was provided with long-term breastfeeding role models and supported by those around her in continuing to breastfeed:

[My decision to keep breastfeeding] has just evolved, I think. Partly because [my son] is such a dedicated feeder, partly because my husband is so supportive and partly because my knowledge has grown. Being a member of ABA has given me the knowledge to defend my decision…and the support network of other mums who have fed…an ‘older’ baby.

(Rebecca, breastfeeding a son, 36 months)

Table 2 presents a summary of the factors that played a role in mothers’ decision to continue breastfeeding.

When asked to describe their original breastfeeding intentions,

five participants (5%) stated that they thought that they would

breastfeed for a long time but had no set idea about how long this

was and eight women (7%) said that their current practice reflected

their original intention with regards breastfeeding duration. Women who had always intended to breastfeed long-term had observed a close family member or friend breastfeed long-term, had an interest in ‘natural’ things that led them to consider breastfeeding for a long time, had read about breastfeeding beyond infancy or knew about the WHO/UNICEF breastfeeding duration recommendations:

I always knew I would be a long-term breastfeeder. My mum breastfed my siblings until they were 2, 3, 4 years old.

My youngest sister was 2 when my first was born so mum

and I were breastfeeding at the same time.

(Niccola, breastfeeding a son, 30 months)

I had come across breastfeeding on demand and extended breastfeeding concepts in books, it made perfect sense

Table 2. Why women continued to breastfeed without an initial intention to do so or despite an original intention not to do soa.

a Responses with eight or more respondents. Women could indicate more than

one applicable answer.

Table 3. Factors that played a role in women’s intention to breastfeed long-terma

a Responses with two or more respondents. Women could indicate more than one

to me as I have a very strong sense of wanting to live as naturally as possible.

(Cassidy, breastfeeding a daughter, 30 months)

I wanted to feed for the recommended 2 years but didn’t have any set idea of stopping then.

(Rochelle, breastfeeding a daughter, 30 months)

The factors involved in mothers’ intention to breastfeed long-term are shown in Table 3.

The impact of previous breastfeeding relationships

Women were asked whether any previous breastfeeding experience had impacted their current breastfeeding relationship. A large proportion of mothers who had breastfed a child prior to the current relationship (67 of 71 women, 94%) stated that the previous breastfeeding relationship had had an impact. For many mothers, not being able to breastfeed a previous child as they had wished made them determined to do things differently with subsequent children:

I was forced…to wean my eldest son…I felt I let him down, me down and did not want to do that again.

(Justine, breastfeeding a son, 28 months)

I…went through a grieving process when I was unable to

breastfeed my first [for as long as I wanted to]. I ensured I

was better informed the second time.

(Jacqui, breastfeeding a daughter, 30 months)

For some mothers, the success of breastfeeding an earlier child changed their understanding of breastfeeding and increased their

confidence. One mother said that her thoughts on breastfeeding prior to the birth of her first child were that:

I wasn’t going to breastfeed at all…I was totally turned off by the idea, quite modest and convinced (correctly) that I was going to have problems. I also believed (incorrectly) that the stuff about working through problems was propaganda. I did not know anyone who had had problems with feeding and successfully worked through it.

However, after having breastfed her first child for 32 months,

her expectations as she anticipated the birth of her second child were very different:

I had quite the opposite view this time around. I had every intention of breastfeeding this child until he chose to wean and it never occurred to me that I would not succeed.

(Dawn, breastfeeding a son, 33 months)

Women also reported that their previous breastfeeding relationship(s) had made them experienced breastfeeders, increased their knowledge of breastfeeding and resulted in them developing a view that breastfeeding was important and long-term breastfeeding desirable:

I was more relaxed this time, had gained more knowledge and support. I learned to trust my body and its abilities.

(Katrina, breastfeeding a son, 27 months)

Table 4. Impact of previous breastfeeding relationships on the current relationshipa.

I had a very positive and long breastfeeding experience with

[my first child]…because I have seen how incredibly special

and fantastic nursing a toddler is I would have persevered no matter what.

(Suzie, breastfeeding a son, 29 months)

Table 4 presents a summary of the ways in which previous

breastfeeding relationships had influenced the current

breastfeeding relationship.

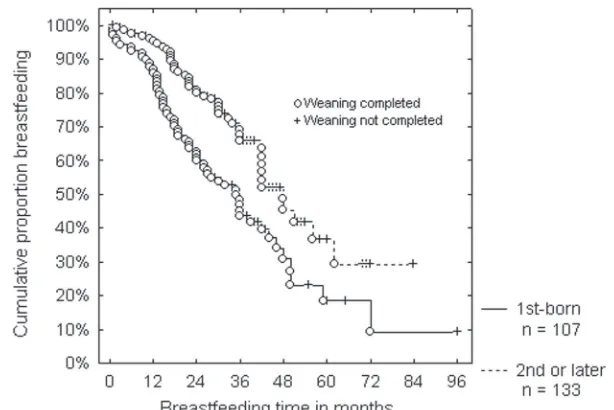

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the breastfeeding durations

of first-born and second- and later-born children of study participants were found to be significantly different from one

another (log-rank test, p< 0.001). This result indicates that second- and later-born children were breastfed for a longer time

than first-born children. Figure 1 shows the relationship between

breastfeeding duration and birth order of the child.

Forty-one women had not breastfed a child prior to the current relationship however, six of these women mentioned knowledge or experience of other breastfeeding relationships such as being breastfed themselves, their husband being breastfed

or their mother breastfeeding a sibling as having influenced their

current breastfeeding relationship.

My mum breastfed me, so I suppose I thought that I can do that too.

(Rebecca, breastfeeding a son, 36 months)

Breastfeeding challenges

Participants were asked to describe the history of the breastfeeding relationship with their current long-term breastfeeding child. From this history, breastfeeding challenges that had been

encountered and overcome were identified. Table 5 shows the challenges described by mothers in the first few weeks of

their current breastfeeding relationship and Table 6 shows the challenges described by mothers later in the relationship. Eighty-one percent of mothers had experienced at least Eighty-one challenge, 6% had experienced two, and 46% had experienced three or more challenges during their current breastfeeding relationship.

Continuity of breastfeeding

Mothers were asked if their child had ever stopped breastfeeding or had weaned for a period of time. Ninety-two children had had a continuous breastfeeding relationship and 22 children had

Table 5. Challenges that mothers faced early in their current breastfeeding relationshipa.

a Women could indicate more than one applicable answer.

b Responses from five or less mothers: child given bottles in hospital, child is

adopted, child refused or preferred one breast, difficult birth, food allergy requiring

dietary restrictions, history of childhood sexual abuse, history of relational trauma

in adopted child, illness in baby, inverted nipple, jaundice, lack of confidence, lack

of support, low supply, multiple birth, NICU care needed, postnatal depression,

reflux, sleepiness due to labour drugs, thrush, tongue tie, use of nipple shield.

ceased breastfeeding for some time from several days to years (one child had stopped breastfeeding twice) as shown in Table 7

DISCUSSION

The mothers in this study were breastfeeding children who were two years of age or older, however, only 12% of them had originally intended to practice long-term breastfeeding. The societal expectation in Australia and other developed countries is that babies breastfeed for only a few months (Hannan et al 200; Hauck & Irurita 2003; Stearns 1999) and it is not socially acceptable to continue breastfeeding beyond this time (Hannan et al 200; Kendall-Tackett & Sugarman 199; Wilson-Clay 1990). It appears that most women in this study embarked upon

motherhood with ideas about breastfeeding duration that reflected

the norms of mainstream Australian society. Study responses indicated that, for many women, breastfeeding beyond infancy was something that had either not occurred to them or was repulsive to them. Research has repeatedly found that women’s pre-birth

breastfeeding intentions are a good predictor of the actual duration of breastfeeding (Donath, Amir & Team 2003; Rempel 2004). However, in this study, even where the subject child was

the first-born, most women had not intended to breastfeed for as

long as they had. It may be that initial breastfeeding intentions are only a good predictor of breastfeeding duration when the total duration is relatively short and that other factors are involved in determining long-term duration.

The reasons why some mothers continue to breastfeed beyond infancy is the source of speculation. Other research has found that the desire of the child to continue breastfeeding is important (Buckley 1992, 2002; Hills-Bonczyk et al 1994) and in this study it was the most common reason mothers gave for delaying weaning. Although the agency of the child can promote breastfeeding continuance it is also common for mothers to direct the termination of breastfeeding before their child indicates a desire to do so (Binns & Scott 2002; Hillervik-Lindquist 1991). Since most mothers in this study had not originally intended to breastfeed long-term, there must have been a change in attitude that resulted in them being willing to continue breastfeeding. Study responses indicated that this attitude change was a gradual process and one in which an increasing knowledge of breastfeeding played an important role. As they learnt about breastfeeding, mothers became aware that it was not abnormal for breastfeeding to continue past early infancy and that even though their child was no longer a small infant, breastfeeding remained valuable. This

motivated them to delay weaning and increased their confidence

in breastfeeding. Health professionals currently provide mothers with a substantial amount of information about infant feeding antenatally and in the immediate post-natal period. However, the experiences of the mothers in this study, would suggest that breastfeeding education should continue throughout the lactation period.

Other factors that assisted mothers to continue breastfeeding were membership of Australia’s peer breastfeeding support organisation, ABA, and long-term breastfeeding role models. Previous research has found that the attitude of others towards

continuing breastfeeding influences mothers’ decision making

concerning when to wean (Bailey, Pain & Aarvold 2004; Morse & Harrison 1987). An environment that is hostile to breastfeeding continuance, such as modern Australian society (e.g. Hauck & Irurita 2003), encourages early weaning. In a hostile environment, social involvement with women who are practicing long-term breastfeeding or with others who support the decision not to wean early, may be essential for mothers to ‘keep going’ (Bottorff 1990). Women may limit contact with those who do not support their decision to delay weaning and actively seek connection with those who will support them as they continue to breastfeed past the culturally accepted duration (Wrigley & Hutchinson 1990). Many of the mothers in this study found people who would support them in breastfeeding beyond infancy in ABA. ABA also provided women with a source of information about breastfeeding and breastfeeding role models, which encouraged them to continue breastfeeding. Being exposed to the breastfeeding experiences of others via peer support organisations such as ABA has been

Table 6. Challenges that mothers faced later in their current breastfeeding relationship. a

a Women could indicate more than one applicable answer.

b Responses from four or less mothers: artificial baby milk supplementation

required, bedwetting, blocked ducts, breast infection, distractibility, eczema, engorgement, feeling touched out, food allergy requiring a restricted maternal diet, fussiness, low weight gain, mastitis, very frequent breastfeeding, white spot.

Table 7. Reasons for and durations of weaning (complete cessation of breastfeeding) in children

found to provide apprenticeship-style learning opportunities

that increase mothers’ breastfeeding knowledge and confidence.

(Blyth et al 2002; Dennis 1999; Hoddinott, Chalmers & Pill 2006; Hoddinott & Pill 1999). In addition to helping women to learn how to physically breastfeed, peer breastfeeding support also assists mothers to integrate breastfeeding into every day life (Hoddinott, Chalmers & Pill 2006) and if breastfeeding is to be continued for more than a short time this is essential. This point underlines the importance of mothers knowing other breastfeeding women if they are to successfully breastfeed. However, a possible limitation of this study is that participant recruitment was via ABA and the fact that the majority of participants were ABA members could bias the results.

Role models who had breastfed long-term assisted mothers to continue to breastfeed beyond infancy themselves. However, as has been found in other research (Buckley 2002), women were

frequently shocked by the first sight of a non-infant breastfeeding.

Despite the often-alarming nature of the initial encounter, it seems that being exposed to long-term breastfeeding is often a necessary part of the process by which women consider the possibility of delaying weaning themselves. Anecdotal evidence suggests that breastfeeding advocates may avoid the presentation of non-infants breastfeeding in education classes or materials because they fear that it would alienate women. However, it may be that without this exposure, many women are unable to continue breastfeeding beyond early infancy. This point would suggest that the sensitive presentation of the normalcy and health and developmental impacts of long-term breastfeeding should be included in all infant feeding education opportunities. Breastfeeding education materials should routinely refer to breastfeeding of ‘infants and young children’ (as opposed to just ‘infants’) and include visual presentation of older babies and young children breastfeeding. In addition, rather than practicing ‘closet nursing’ (Buckley 2002), mothers breastfeeding older babies and toddlers should be encouraged to breastfeed in public because such action will support breastfeeding continuance in other mothers.

There was a small group of women in this study who had always intended to breastfeed beyond infancy. Long-term breastfeeding was common amongst the family and friends of many of these women creating a subculture within which breastfeeding beyond infancy was normal and expected. This experience is similar to that of mothers raised in non-industrialised cultures where early weaning is uncommon (Buckley 2002). It is clear that the social context of infant feeding moulds the expectations of parents (de Monleon 2002). The social context can have a positive impact where it supports breastfeeding; however, it will have a negative impact where it supports bottle-feeding (Bailey, Pain & Aarvold 2004; Dix 1991). Women who were raised primarily within a family or social network where bottle-feeding is normal have had their infant feeding and behavioural expectations framed in terms of bottle-feeding. Women with this history may need assistance to reframe their expectations in such a way as to enable breastfeeding success (Bailey, Pain & Aarvold 2004). Antenatal exploration of the infant feeding practices of a mother’s close associates may assist health professionals to identify women who

are at a particular risk of early weaning. Mothers thought to be at risk should be encouraged to join a peer breastfeeding support organisation or otherwise to seek association with women who are experienced breastfeeders in order to develop a social context that will support them in breastfeeding.

Mother’s previous breastfeeding experience played a role in determining breastfeeding duration and women breastfed

second and subsequent children for longer than their first-born

child. Positive breastfeeding experiences have been found to

increase women’s knowledge of breastfeeding and confidence in

breastfeeding (Blyth et al 2002; Stearns 1999) and in general, the

more confident a woman is the longer she breastfeeds (Blyth et

al 2002; Blyth et al 2004). Other research has also found that breastfeeding duration increases with parity (Ford & Labbok 1990; Kronborg & Vaeth 2004). In this study, mothers were explicit in describing how their prior positive breastfeeding experiences had contributed to their current breastfeeding success. However, research has also found that where mothers have had a negative

breastfeeding experience, this can decrease their confidence

in their ability to breastfeed and reduce the likelihood of them successfully breastfeeding subsequent children (Blyth et al 2002; da Vanzo, Starbird & Leibowitz 1990; Dennis 1999; Simard et al 200). There were a number of women in this study who had

previously had difficult and brief breastfeeding experiences but

these negative experiences had made them determined to make subsequent breastfeeding relationships more successful and they had done so. The ability of some women to successfully breastfeed in spite of earlier traumatic or disappointing experiences deserves further investigation.

Women who were breastfeeding their first child did not have previous experience as a mother on which to reflect. However, several first-time mothers indicated that the fact that their mother had breastfed had contributed to them feeling confident about

breastfeeding themselves. Research has found that having been breastfed as an infant increases the probability of a woman breastfeeding her own children (Batal & Boulghaurjian 200;

Batinica et al 2002; Berra et al 2003). This finding may be related

to the support grandmothers provide to their daughters (Tiedje

et al 2002) as well as to the confidence that mothers gain from

their mother’s experience. Thus, there may be both a between-child and intergenerational impact of breastfeeding success and those who assist a mother to breastfeed her baby may not just be assisting her to breastfeed that child but may also be having an impact on her ability to breastfeed her subsequent children.

Even more significantly, they may also be assisting her daughters

to breastfeed her grandchildren.

The breastfeeding histories of the women in this study showed that nearly all had faced at least one challenge in their current breastfeeding relationship and many had experienced several. As

has been found in other research, difficulties with attachment and

nipple pain are common experiences (Dennis 2002). However, there was a large variety of challenges that mothers had faced and

overcome, some requiring significant exertion and persistence. While breastfeeding challenges have been identified as one of

this study were able to overcome these challenges and continue

breastfeeding. This study did not specifically examine how these

women overcame challenges; however other research and mothers’ descriptions of how they came to breastfeed long-term provide some clues. It can be speculated that these women were able to continue breastfeeding because they had the motivation to continue

(Bottorff 1990), confidence in their ability to breastfeed (Blyth et

al 2002; Dennis 1999) and timely, appropriate support (Tiedje et al 2002). This study shows that it is far from the case that long-term breastfeeders are those who have found breastfeeding easy. Rather it demonstrates that while breastfeeding challenges are extremely common they do not necessarily result in the termination of breastfeeding (Bailey, Pain & Aarvold 2004; Tiedje et al 2002). Further research is needed to clarify how and why some women are able to overcome challenges and avoid premature weaning, when

other women faced with similar difficulties wean.

Insufficient milk supply has been identified as the most

common challenge responsible for early weaning (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2003; Binns & Scott 2002; Blyth et al 2002; Heath et al 2002; Hillervik-Lindquist 1991; Obermeyer & Castle 1996). However, few women in this study reported that they had experienced low milk supply. The infrequency with which mothers

reported insufficient milk may be because this is a challenge

that few women overcome and therefore such women were not represented in this study. Alternatively, the scarcity of reports of low milk supply may indicate that the women in this study were supported in a way that allowed them to avoid this challenge.

Research has found that a perception of insufficient milk may not be a real insufficiency (Hillervik-Lindquist, Hofvander & Sjolin

1991) but a result of a misinterpretation of infant behaviour (Tully & Dewey 198). Otherwise, iatrogenic causes such as restricting

breastfeeding frequency can cause milk insufficiency (Dykes

& Williams 1999; Millard 1990; Obermeyer & Castle 1996) or mothers may report that they had low milk supply because this is considered a socially acceptable reason for weaning (Hoddinott

& Pill 1999; McLennan 2001). Perceived insufficient milk supply is a phenomenon associated with low confidence and support

for breastfeeding (Blyth et al 2002). The mothers in this study may have been able to avoid this problem because they had a

high level of motivation, knowledge and confidence with regards

breastfeeding. Women not associated with peer breastfeeding

support groups are much more likely to report insufficient milk

supply (Ladas 1972). That many of the women in this study were members of ABA or had other social support for breastfeeding may account for the low proportion that reported that they had experienced low milk supply.

Breastfeeding is often considered a continuous process from initiation of breastfeeding to full weaning. However, this study demonstrated that it is not uncommon for breastfeeding to be discontinuous with children weaning from the breast for days to years before recommencing breastfeeding. Previous researchers have noted cases where breastfeeding has resumed after weaning (Marquis et al 1998; Phillips 1993; Thorley 1997) but the incidence

of discontinuous breastfeeding has not previously been identified.

In this study there were 23 cases where breastfeeding had ceased

at some stage, representing 19% of children. This finding indicates

that it may be common for breastfeeding to be discontinuous when it is long-term. This information should be routinely provided to mothers so that they know that breast refusal, maternal separation or weaning during pregnancy, may not mean the end of breastfeeding.

CONCLUSION

This study provides insight into the experiences of Australian women who have successfully breastfed their children for the duration recommended by WHO/UNICEF. Most of these mothers had not originally intended to breastfeed long-term, but had changed their goals and opinions postnatally about how long

they would breastfeed for. These findings suggest that postnatal

interventions may be successful in increasing breastfeeding duration. Such interventions might include continuing provision of breastfeeding information throughout the lactation period, facilitation of exposure to long-term breastfeeding, and referral to peer breastfeeding support organisations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the Australian Breastfeeding Association for allowing participant recruitment via the Association, the mothers who so kindly shared their experiences and Dr John Bidewell for statistical assistance.

REFERENCES

Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Remley DT 1999, Breast-feeding

and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr

70: 2–3.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2003, Breastfeeding in Australia, 2001. ABS, Canberra.

Bailey C, Pain R, Aarvold J 2004, A ‘give it a go’ breast-feeding culture and early cessation among low-income mothers.

Midwifery 20: 240–20.

Batal M, Boulghaurjian C 200, Breastfeeding initiation and

duration in Lebanon: are the hospitals “mother friendly”? J

Pediatr Nurs 20: 3–9.

Batinica M, Grguric J, Bozikov J, Zakanj Z, Lipovac D, Vincekovic V, Batinica R, Turcinov E 2002, Intergenerational transmission of breastfeeding as a behavioral model. Lijecnicki Vjesnik

124: 10–1.

Berra S, Sabulsky J, Rajmil L, Passamonte R, Pronsato J, Butinof M 2003, Correlates of breastfeeding duration in an urban

cohort from Argentina. Acta Paediatr 92: 92–97.

Binns CW, Scott JA 2002, Breastfeeding: reasons for starting,

reasons for stopping and problems along the way. Breastfeed

Rev 10: 13–19.

Blyth R, Creedy DK, Dennis CL, Moyle W, Pratt J, De Vries

SM 2002, Effect of maternal confidence on breastfeeding duration: an application of breastfeeding self-efficacy theory.

Birth 29: 278–284.

Blyth RJ, Creedy DK, Dennis CL, Moyle W, Pratt J, De Vries SM, Healy GN 2004, Breastfeeding duration in an Australian population: the

Bottorff JL 1990, Persistence in breastfeeding: a phenomenological investigation. Journal of Adv Nurs 1: 201–209.

Briend A, Bari A 1989, Breastfeeding improves survival, but not nutritional status, of 12-3 months old children in rural Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Nutr 43: 603–608.

Buckley KM 1992, Beliefs and practices related to extended

Callen J, Pinelli J 2004, Incidence and duration of breastfeeding for term infants in Canada, United States, Europe, and Australia: a literature review. Birth 31: 28–292.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer 2002, Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 0302 women with breast cancer and

96973 women without the disease. Lancet 360: 187–19.

Cumming RG, Klineberg RJ 1993, Breastfeeding and other reproductive factors and the risk of hip fractures in elderly

women. Int J Epidemiol 22: 684–691.

da Vanzo J, Starbird E, Leibowitz A 1990, Do women’s

breastfeeding experiences with their first-borns affect whether

they breastfeed their subsequent children? Soc Biol 37: 223– 232.

de Monleon JV 2002, [Breastfeeding and culture]. Archives de Pediatrie 9: 320–327.

Dennis CL 1999, Theoretical underpinnings of breastfeeding

confidence: a self-efficacy framework. J Hum Lact 1: 19– 201.

Dennis CL 2002, Breastfeeding initiation and duration: a

1990-2000 literature review. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 31:

12–32.

Dewey KG 2003, Is breastfeeding protective against child obesity?

J Hum Lact 19: 9–18.

Dix DN 1991, Why women decide not to breastfeed. Birth 18:

222–22.

Donath SM, Amir LH, Team AS 2003, Relationship between prenatal infant feeding intention and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a cohort study. Acta Paediatr 92: 32–36. Dykes F, Williams C 1999, Falling by the wayside: a

phenomenological exploration of perceived breast-milk

inadequacy in lactating women. Midwifery 1: 232–246.

Feachem RG, Koblinsky MA 1984, Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: promotion of breast-feeding. Bull World Health Organ 62: 271–291. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT 1987, Breastfeeding

and subsequent social adjustment in six- to eight-year-old children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 28: 379–386.

Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ 1999, Breast feeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 13: 144– 17.

Ford K, Labbok M 1990, Who is breast-feeding? Implications of associated social and biomedical variables for research on the

consequences of method of infant feeding. Am J Clin Nutr

2: 41–46.

Goldman AS, Goldblum RM, Garza C 1983, Immunologic components in human milk during the second year of lactation. Acta Paediatr Scand 72: 461–462.

Gribble K 2006, Mental health, attachment and breastfeeding: implications for adopted children and their mothers. Int Breastfeed J 1: .

Hannan A, Li R, Benton-Davis S, Grummer-Strawn L 200, Regional variation in public opinion about breastfeeding in the United States. J Hum Lact 21: 284–288.

Harder T, Schellong K, Plagemann A 2006, Differences between meta-analyses on breastfeeding and obesity support causality of the association. Pediatrics 117: 987.

Hauck YL, Irurita VF 2003, Incompatible expectations: the

dilemma of breastfeeding mothers. Health Care Women Int

24: 62–78.

Heath AL, Tuttle CR, Simons MS, Cleghorn CL, Parnell WR 2002, A longitudinal study of breastfeeding and weaning practices

during the first year of life in Dunedin, New Zealand. J Am Diet Assoc 102: 937–943.

Hillervik-Lindquist C 1991, Studies on perceived breast milk

insufficiency. A prospective study in a group of Swedish

women. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 376: 1–27.

Hillervik-Lindquist C, Hofvander Y, Sjolin S 1991, Studies on

perceived breast milk insufficiency. III. Consequences for

breast milk consumption and growth. Acta Paediatr Scand 80: 297–303.

Hills-Bonczyk SG, Tromiczak KR, Avery MD, Potter S, Savik K, Duckett LJ 1994, Women’s experiences with breastfeeding longer than 12 months. Birth 21: 206–212.

Hoddinott P, Chalmers M, Pill R 2006, One-to-one or group-based peer support for breastfeeding? Women’s perceptions of a breastfeeding peer coaching intervention. Birth 33: 139– 146.

Hoddinott P, Pill R 1999, “Nobody actually tells you”: a qualitative

study of infant feeding experiences of first time mothers.

British Journal of Midwifery 7: 8–6.

Huo D, Lauderdale DS, Li L 2003, Influence of reproductive

factors on hip fracture risk in Chinese women. Osteoporos

Int 14: 694–700.

Karlson EW, Mandl LA, Hankinson SE, Grodstein F 2004, Do

breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future

risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Nurses’ Health

Study. Arthritis Rheum 0: 348–3467.

Kendall-Tackett KA, Sugarman M 199, The social consequences of long-term breastfeeding. J Hum Lact 11: 179–183.

Kronborg H, Vaeth M 2004, The influence of psychosocial factors

on the duration of breastfeeding. Scand J Public Health 32: 210–216.

Lande B, Andersen LF, Veierod MB, Baerug A, Johansson L, Trygg KU, Bjorneboe GE 2004, Breast-feeding at 12 months of age and dietary habits among breast-fed and non-breast-fed infants. Public Health Nutr 7: 49–03.

Lavelli M, Poli M 1998, Early mother-infant interaction during breast- and bottle-feeding. Infant Behav Dev 21: 667–684. Lepage P, Munyakazi C, Hennart P 1981, Breastfeeding and

hospital mortality in children in Rwanda. Lancet 2: 409–411. Marquis GS, Diaz J, Bartolini R, Creed de Kanashiro H, Rasmussen

KM 1998, Recognizing the reversible nature of child-feeding decisions: breastfeeding, weaning, and relactation patterns in a shanty town community of Lima, Peru. Soc Sci Med 47: 64–66.

McLennan JD 2001, Early termination of breast-feeding in periurban Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: mothers’ community perceptions and personal practices. Pan Am J Public Health 9: 362–367.

Millard AV 1990, The place of the clock in pediatric advice: rationales, cultural themes, and impediments to breastfeeding.

Soc Sci Med 31: 211–221.

Molbak K, Gottschau A, Aaby P, Hojlyng N, Ingholt L, da Silva AP 1994, Prolonged breast feeding, diarrhoeal disease, and survival of children in Guinea-Bissau. BMJ 308: 1403–1406. Morse JM, Harrison MJ 1987, Social coercion for weaning. J

Nurse Midwifery 32: 20–210.

Obermeyer CM, Castle S 1996, Back to nature? Historical and cross-cultural perspectives on barriers to optimal breastfeeding.

Med Anthropol 17: 39–63.

Oddy W 2006, Fatty acid nutrition, immune and mental health development from infancy through childhood. In Huang JD (ed) Frontiers in Nutrition Research. Nova Science Publishers, New York.

Phillips V 1993, Relactation in mothers of children over 12 months. J Trop Pediatr 39: 4–48.

Rempel LA 2004, Factors influencing the breastfeeding decisions

of long-term breastfeeders. J Hum Lact 20: 306–318. Simard I, O’Brien HT, Beaudoin A, Turcotte D, Damant D,

Ferland S, Marcotte MJ, Jauvin N, Champoux L 200, Factors

influencing the initiation and duration of breastfeeding among

low-income women followed by the Canada prenatal nutrition

program in 4 regions of Quebec. J Hum Lact 21: 327–337.

Stearns CA 1999, Breastfeeding and the good maternal body.

Gend Soc 13: 308–32.

Stuebe A, Michels K, Willett W, Manson J, Rich-Edwards J 2006, Duration of lactation and incidence of myocardial infarction.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 19: S34.

Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Manson JE, Michels KB 200, Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2

diabetes. JAMA 294: 2601–2610.

Thorley V 1997, Relactation and induced lactation: what the exceptions can tell us. Birth Issues 6: 24–29.

Tiedje LB, Schiffman R, Omar M, Wright J, Buzzitta C, McCann A, Metzger S 2002, An ecological approach to breastfeeding.

Am J Matern Child Nurs 27: 14–161.

Tully J, Dewey KG 198, Private fears, global loss: a cross-cultural

study of the insufficient milk syndrome. Med Anthropol 9: 22–243.

Tung KH, Wilkens LR, Wu AH, McDuffie K, Nomura AM,

Kolonel LN, Terada KY, Goodman MT 200, Effect of anovulation factors on pre- and postmenopausal ovarian cancer risk: revisiting the incessant ovulation hypothesis. Am J Epidemiol 161: 321–329.

von Kries R, Koletzko B, Sauerwald T, von Mutius E, Barnert D, Grunert V, von Voss H 1999, Breast feeding and obesity: cross sectional study. BMJ 319: 147–10.

WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality 2000, Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less

developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet 3: 41–4.

WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group 2006, WHO child growth standards based on length/height, weight and

age. Acta Paediatr Supp 40: 76–8.

Wilson-Clay B 1990, Extended breastfeeding as a legal issue: an annotated bibliography. J Hum Lact 6: 68–71.

World Health Organization 1998, Complementary Feeding of

Young Children in Developing Counties: a Review of Current

Scientific Knowledge World Health Organization, Geneva.

World Health Organization & UNICEF 2003, Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding World Health Organization, Geneva.

Wrigley EA, Hutchinson SA 1990, Long-term breastfeeding. The

secret bond. J Nurse Midwifery 3: 3–41.

Zheng T, Duan L, Liu Y, Zhang B, Wang Y, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Owens PH 2000, Lactation reduces breast cancer risk in

Shandong Province, China. Am J Epidemiol 12: 1129–

113.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: