A Signaling Perspective

on Partner Selection

in Venture Capital

Syndicates

Christian Hopp

Christian Lukas

This paper analyzes the factors impacting partnering decisions in venture capital syndicates using a unique data set of 2,373 venture capitalist (VC) transactions in Germany. We employ a signaling perspective to partner-selection strategies within VC syndicates. By including time-varying information about industry experience and cooperation patterns, we explicitly take into account not only the changing social context for partner selection, but also the dynamic nature of signals sent and received. Our analysis documents that the informative-ness of investment experience as a signal depends on the existence and frequency of previous joint deals with the lead VC. Experience becomes a much stronger signal if previous invitations to syndicates are bilateral rather than unilateral. The willingness to invite others to deals signals the ability to reciprocate through one’s own deal flow. More-over, we show how the value of signals erodes over time, that is, information from the previous year carries more informational value than signals from more distant years. In sum, the data reveal that different signals carry weight for lead VCs, and that the frequency of signals sent and the stage of development of the portfolio firm positively moderate the value and relevance of signaling behavior. While early stage investments are mainly characterized by need to diversify and to spread risks, value-added advice is necessary in later rounds, and hence, the strength of the signals sent and received gain in relevance and in value.

Introduction

The syndication of venture capital involves cooperation between partner venture capitalists (VCs) who jointly finance promising growth companies. Their relationship is characterized by uncertainty over the prospects of the ventures they fund, and the con-siderable time and effort they apply to guiding and advising the entrepreneurs (Ferrary, 2010; Gompers & Lerner, 2002; Manigart et al., 2005). There are various ways in which VCs can benefit from each other, in terms of sharing financial and managerial resources (Brander, Antweiler, & Amit, 2002; Lerner, 1994) or sharing risk (Manigart et al.). As VCs are mutually dependent on each other, it is important to choose the best possible

Please send correspondence to: Christian Hopp, tel.:+43-1-4277-38166; e-mail: [email protected].

P

T

E

&

1042-2587

partner(s). The decision of whom to invite to participate in VC transactions lies at the heart of understanding why syndication adds value to the funded firm. However, a major problem associated with a lead VC’s partnering decision is uncertainty and information asymmetry.

Generally, information asymmetry is also present in the entrepreneur’s decision of whom to invite to join the young firm’s team, or whom to choose as financier; and for the decision by a financier—be it a VC, bank, or business angel—of which entrepreneur to fund. The common feature of these examples is that the information available about the quality of a potential partner or project differs between contracting partners, and in general, the party making the selection decision possesses less information. However, the party making the selection may use additional observable information to infer the part-ner’s or the project’s quality. Such a situation conforms to the typical setup analyzed in signaling theory: There is information asymmetry between contracting parties, and it can be reduced by signals that are observable and known in advance (Certo, 2003; Certo, Daily, & Dalton, 2001; Spence, 1974). For example, Kaplan and Strömberg (2004) show thatex-ante(i.e., within-round) staging of deals may allow very professional VC firms to signal their type to entrepreneurs. Another signal is the presence of a VC, which helps to verify that a young firm is not holding back initial public offering (IPO)-relevant information (Megginson & Weiss, 1991). In their meta-analysis, Daily, Certo, Dalton, and Roengpitya (2003) review a number of studies evaluating possible signals of IPO quality, like firm size, auditor reputation, and venture capital equity. Certo proposes board struc-ture as an important signal in that context. Following Filatotchev and Bishop (2002), share ownership of board members represents a signal of the young firm’s quality. However, depending on institutional factors, the value of otherwise-identical signals in different IPOs may vary (Moore, Bell, & Filatotchev, 2010). When judging the prospects of young firms, financiers may also consider the investment behavior of entrepreneurs (Prasad, Bruton, & Vozikis, 2000) or new venture teams (Busenitz, Fiet, & Moesel, 2005), VC funding events (Davila, Foster, & Gupta, 2003), and/or the status and reputation of VCs (Dimov & Milanov, 2009). Hence, signals can in general mitigate information asymmetry involved in entrepreneurial financing.

More particularly, in VC partnering decisions, the lead VC thinking about whether to select a partner can also turn to observable signals such as records of deals, status and reputation, or board composition to cope with and reduce information asymmetry.1

Valliere (2011) demonstrates that success in early stage financing constitutes a signal of the VC’s ability to screen investment proposals; Manigart et al. (2005) argue that an invitation from a reputable lead investor could be a valuable signal of the quality of a nonlead investor.

The theoretical literature on VC syndication places great emphasis on experience as a signal for the selection of potential partner VCs (Booth, Orkunt, & Young, 2004; Casamatta & Haritchabalet, 2007; Cestone, White, & Lerner, 2006; Dorobantu, 2006). In practice, however, experience is likely to be an imperfect proxy for the quality of a VC; other signals are available, embedded in the wider investment context. The question arises of when and how the signal “experience” can be strengthened so that it better helps to infer the quality of a VC as a potential partner before a syndication decision is made.

In this paper, we are particularly interested in one part of the asymmetric information that VCs face, namely adverse selection in partnering decisions when one party lacks skills in selecting or managing deals, yet claims to possess these abilities. One way that

this information asymmetry is overcome is through the emission of signals via actions that reveal the true quality of VCs. Our approach builds upon theoretical advancements in signaling behavior by testing how market actions affect the syndication behavior of VCs (Basdeo, Smith, Grimm, Rindova, & Derfus, 2006; Clark & Montgomery, 1998; Stiglitz, 2002). In line with Basdeo et al. and Milgrom and Roberts (1982), we propose that market actions act as a signal to reveal unobservable VC attributes. By market actions, we specifically refer to the frequency of VC investments and the sharing of deal flow, alone and, more importantly, in combination.

We analyze the partnering decision in VC syndicates using a unique sample of 2,373 venture capital transactions in Germany. The underlying units of analysis are the syndi-cates of VCs formed during the period of 1995–2005. We address the questions of which partner VC(s) the lead investor chooses and which characteristics of the potential partner influence the likelihood of collaboration.

Our results suggest that signaling in venture capital investing comprises continuous investments to develop one’s own competence, subsequently engaging in relationships with other VC partners in syndicate transactions, being able and willing to reciprocate and act as lead investor, and lastly being able to continuously make this effort of ambidex-trously managing networking resources and individual investments. Based on our find-ings, different combinations of signals can spur cooperation between VCs. Especially a combination of signals of quality and intent—industry experience and reciprocation— strongly increases the probability of cooperation.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. We first introduce the theoretical background and develop the hypotheses. Next, we present the data set, the variables used, and the methodology. A presentation of the regression results follows, along with a discussion of and our findings, potential limitations and avenues for future research, and a conclusion.

Theoretical Background

Analyzing the decisive factors in partner-selection processes certainly represents a promising way to get an understanding of why syndication adds value to a VC-backed firm. As current and desired expertise forms the basis of value creation in the VC market, the VCs’ strategic actions are characterized by new opportunities and the corresponding competencies to master them. Related work argues that VCs are likely to lack (at least to some extent) potential resources, such as technological or invest-ment expertise, that are needed to achieve long-term competitive advantages; they refer to the ability to earn above-normal economic rents through the exploitation of capa-bilities or financial resources to provide adequate financing (Ferrary, 2010; Manigart et al., 2005). Accordingly, interorganizational relationships (syndicates) can create value by allowing VCs to combine resources and to share knowledge (Brander et al., 2002; Manigart et al.). While a VC’s internal resources are key to acquiring and sustain-ing competitive advantages, when those resources are lacksustain-ing, alternative routes of generating and accessing knowledge are needed to prosper (Barney, 1991; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978).

opportunism2) and foregone potential returns. Pichler and Wilhelm (2001) demonstrate

theoretically that restricting access to syndicates may be Pareto optimal due to moral hazard concerns; Meuleman, Wright, Manigart, and Lockett (2009) analyze empirically when the agency costs of syndication exceed its benefits. Syndication unavoidably entails giving up some of the expected profits to partner VCs (Brander et al., 2002). Casamatta and Haritchabalet (2007) and Cestone et al. (2006) found that more experi-enced VCs are less likely to syndicate, while less experiexperi-enced VCs would want to reap the benefits of the formers’ more reliable evaluation of a venture’s success prospects. Yet there may be situations where inexperienced VCs never syndicate (Dorobantu, 2006). Hence, despite the possible lack of resources, many firms do not enter into interfirm relationships because the costs associated with partner selection do not out-weigh the benefits of getting access to new knowledge (Barringer & Harrison, 2000; Dimov & Milanov, 2009).

Given the earlier arguments, a major problem associated with the decision of whom to select in a syndicate is to find out exactly what resources a VC can contribute and what the level of the quality of those resources is. It is easy to calculate financial resources, but much harder to calculate nonfinancial resources such as knowledge, familiarity with sector-specific factors, and the ability to analyze, guide, and decide. These latter hard-to-measure and hard-to-communicate characteristics naturally give rise to an information asymmetry between partners in a syndicate. Even if a VC wishes to communicate truth-fully, it may not be possible (Busenitz et al., 2005; Williamson, 1991a) because “the limits of language are real” (Williamson, 1991b, p. 168).

Consequently, the lead VC selecting a partner has to cope with information asymme-try (Ferrary, 2010; Keil, Maula, & Wilson, 2010). The signaling theory offers a solution to the problem. It suggests that the better-informed party provides additional information (“signals”) to better communicate its own quality to less-informed parties (Certo et al., 2001; Spence, 1973, 1974). The receiver is referred to as the external, less-informed party, and the sender is referred to as the internal, better-informed party emitting the signal. In order to be valuable, signals must be freely accessible (i.e., observable), understood in advance, and costly to imitate (Certo et al.; Connelly et al., 2010). In the VC context, observability may be accomplished by communicating deal flows into the VC network (Ferrary; Hochberg, Ljungqvist, & Lu, 2007). Signals meet the costly-to-imitate criterion if they entail positive costs, and these costs or the benefits derived from the signals are type dependent (Spence, 2002). A VC’s deal record certainly cannot be replicated at zero costs because generating a deal flow requires effort; different VCs may incur different costs due to differences in abilities. But even if they have identical costs, in terms of amount invested, or labor costs for offering advice, VCs are likely to receive different returns (Cochrane, 2005; Hochberg et al.). Here the quality of advice as a resource matters, and it largely determines the possible benefits.

In our study we adopt a broad notion of VC quality and understand it as an “under-lying, unobservable ability . . . to fulfill the needs or demands of an outsider observing the signal” (Connelly et al., 2010, p. 43), where potential partner VCs form the group of

outsiders. We treat a VC financing event as the basic signal about the experience of a VC and consider it a proxy of VC quality. Obviously, the more often a VC becomes involved in financing events, the more often he faces situations where information has to be collected and analyzed, and based on this information, decisions have to be made (Fried & Hisrich, 1994). Also, more financing events lead to more frequent interaction with entrepreneurs and partner VCs. According to Gorman and Sahlman (1989), every year a lead VC spends an average of 112 hours in direct contact with the entrepreneur, either on site or over the phone, and makes an average of 19 visits to the entrepreneur. For nonlead and late-stage VCs, these numbers are substantially lower but still significant. VCs learn from these experiences (Fried & Hisrich; Sahlman, 1990) so that experienced VCs are better able to screen investment proposals (Tyebjee & Bruno, 1984) and hence improve their quality. At the same time, outsiders will update their beliefs about the VC’s quality correspondingly. In addition, given that financing events are informative signals about the funded firm’s quality (Davila et al., 2003), they should indicate the VC’s quality as well since the two are likely to be correlated. If more signals are made observable, i.e., more financing events are communicated into a VC network (Ferrary, 2010; Hochberg et al., 2007), receivers can better infer the quality of the signal-emitting VC—in other words, sending signals frequently to the VC market strengthens the signal (Connelly et al.; Janney & Folta, 2003). Syndication would be another way to improve signal effectiveness and to reduce information asymmetry. Joint work offers the chance to observe or learn the characteristics of partner VCs through direct interaction and possibly in different roles (lead VC or nonlead VC). It provides additional valuable information beyond the mere fact that a particular VC worked on a particular deal. Syndication, however, entails the disadvantage of sharing profits with partner VCs, thereby increasing the costs of signaling. The basic idea behind our partner selection model is that a lack of resources triggers the quest for partner VCs. Since characteristics of VCs cannot easily be observed or communicated, information about them remains private, giving rise to information asym-metry. Signaling offers a way to deal with this problem. In light of the previous con-siderations, a lead VC considers the following properties of potential partners

•

experience levels in different industries,•

history of syndicating activity, including existence of joint deals,•

willingness to provide access to deal flow,•

the frequency of signal occurrence, and•

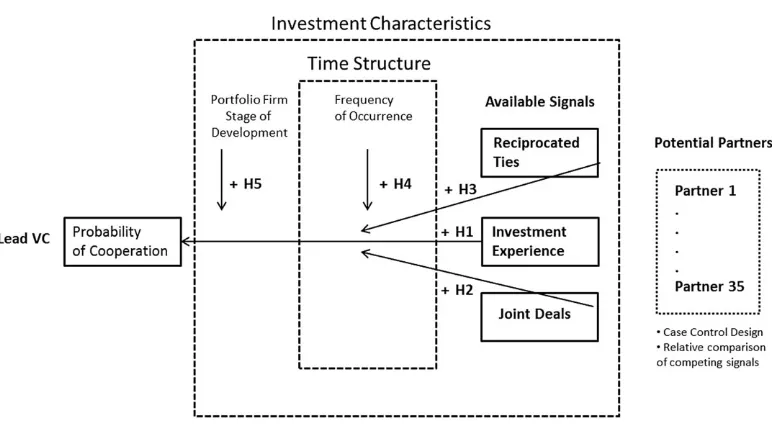

the stage of development of the portfolio firm and corresponding signal relevance to assess their quality. The more precise that assessment, the higher the likelihood of a good partnering decision, which is vital for the success of a VC syndicate. Furthermore, most of these signals result from actions and hence may be worth more than words (Busenitz et al., 2005). Figure 1 presents a stylized depiction of our theoretical model linking various competing signals to the probability of cooperation between a given lead VC and a potential selection from a universe of partners.(Janney & Folta, 2003). Moreover, the development stage of the portfolio firm positively moderates the value of signals. In later stages that involve lower levels of uncertainty about the portfolio firm signals about partner ability to provide value-adding advice become more relevant (Connelly et al., 2010; Lester, Certo, Dalton, Dalton, & Cannella, 2006). To account for potential partners conveying signals relative to each other (higher quality firms signaling at the expense of lower quality firms), we employ a case control design and account for relative strength of signalsvis-à-viscompetitors and the receiver (Connelly et al.; Sorenson & Stuart, 2008; Stiglitz, 2002).

Hypotheses

Experience Level

The inherent resources and investment experience of VCs form the basis for strategic value creation and address corresponding demands of entrepreneurs. In fact, better resources allow VCs to provide better advice and/or to better screen business proposals to generate superior long-term returns for fund shareholders (Brander et al., 2002; Lerner, 1994). Investment experience within a particular industry yields valuable insights into structuring deals and advising the funded entrepreneur, so it is crucial for understanding how resources shape competitive advantages in entrepreneurial financing. Therefore, investment experience likely signals the ability of a potential partner VC and helps the lead VC to distinguish between high-quality and low-quality VCs in the market. Having high-quality VCs in the syndicate would enhance the expected profitability of a deal by reducing the probability that partners do not live up to expectations (Lerner), and thereby increasing the chances for cooperation among a lead VC and potential partners (Dimov & Milanov, 2009). In a similar vein, Casamatta and Haritchabalet (2007) show analytically that a lead VC who lacks a needed competence is more likely to choose a partner who possesses that competence.

Figure 1

Hence, we argue that the experience potential partners have gained within a transaction-relevant industry (possibly in excess of the lead investor’s existing knowl-edge) should be positively related to the likelihood of being chosen as a syndicate member. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: More investment experience of a potential partner within the given transaction-relevant industry increases the likelihood of collaboration with a given lead VC.

History of Syndicating Activity

Given the opaqueness of the market, some VCs use their investment strategy to obfuscate information. Less able VCs might actively engage in a large number of trans-actions to look attractive to potentially superior partners. The search for investment transactions not only documents what firms prefer, but also affects the belief of others about them. Due to the long time horizon and the difficulty of disentangling bad luck from a lack of managerial skills in VC investing, a large number of deals do not necessarily yield full information to separate less able from more able VCs.

One of the key elements of signaling when firms have incentives to mislead others about their true ability is to create a set of choices through which firms with different character-istics self-select and reveal their ability. Following this underlying logic, VC firms that are less able in sourcing, evaluating, and managing transactions will act differently from VCs that possess the necessary skills to strive. While VC firms do reveal their track record, the market is fairly opaque and returns are difficult to verify (Cochrane, 2005). Given that talk is literally cheap, less able VC firms do not necessarily have incentives to fully reveal their abilities.3Consequently, market actions are the necessary mechanisms through which better

able VCs can reveal their true abilities.4One way to overcome these deficient signals is to

engage in ongoing syndication activities with other VCs to signal quality to potential partners (Granovetter, 1994; Hanneman & Riddle, 2005; Podolny, 1994). Recent work by Hochberg et al. (2007) reports higher returns for well-connected VCs. This finding under-scores the value of signaling in venture capital markets: More able VCs will receive higher returns for their investments if they can establish that they are more productive.

Previous exchanges between partners mirror the joint history of deals. As argued earlier, direct interactions allow for a more precise assessment of a partner’s quality than the mere observation that the partner participated in or initiated a certain financing event. The interactions may even help to get to know a VC’s founding team characteristics, which are predictors of a VC’s future success (Walske & Zacharakis, 2009). Hence, a joint deal history should matter for upcoming partnering decisions and increase the strength of experience as a base signal.

Accordingly, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: A joint history of syndicating activity between the lead VC and a potential partner positively moderates the value of experience as a base signal and increases the likelihood of collaboration with the given lead VC.

3. Incentives to misrepresent ability exist for less able VC firms when the expected gains from falsely claiming high quality outweigh the losses suffered in the event of detection, leading to a pooling equilibrium (Kirmani & Rao, 2000; Spence, 2002; Stiglitz, 2002).

Deal flow and the willingness to let others participate also convey valuable information to the market. It then seems natural to ask whether inviting or both inviting and being invited to a deal makes a difference. In other words, does the relative strength of the quality signal increase through reciprocation of an invitation? In the event of recipro-cation, the current lead VC has observed the potential partner in different roles, as lead VC and as nonlead VC. One could argue that seeing a partner in different roles helps to assess the quality better. Moreover, the number of deals that VCs are willing to jointly invest in reveals information about the quality of the deals sourced and, hence, the ability of the corresponding VCs. In fact, the willingness to invite others to deals signals the ability to reciprocate through one’s own generated deal flow and is therefore a stronger signal than the pure ability to invest in as many firms as possible. Thus, better infor-mation about the ability of a VC is disclosed not only when investments were made in the past, but also when a willingness to let other VCs participate in deal flow was shown. In essence, less able VCs will not be willing to let other firms participate in their transactions, as they will reveal to partners the characteristics of the transactions chosen. Signaling through actions of VCs is costly and more importantly, more costly for some than others.

Hence, actions of superior VCs need to be more costly or more profitable to signal ability and achieve a separating equilibrium (Spence, 2002). Work by Basdeo et al. (2006) reveals that the complexity of one’s actions affects how they are perceived by the market, as they are more difficult for competitors to imitate. In general, the costs of signaling are borne by high-quality firms to separate themselves from low-quality firms. Given the time lag between deals entered into and the point at which success/failure is discovered, signaling deals undertaken do not suffice as a strong enough signal to actually achieve a separating equilibrium. The discrepancy between the initial signal and subsequent actions may lead to decoupling. While VCs signal quality through previous investments, the reluctance to provide deal flow renders the signal sent erroneous. In other words, the pure presence of experience without reciprocated ties is only a weak signal due to decoupling concerning the abilities present and the sought-after quality of experience or deal flow within the VC market (Connelly et al., 2010; Hochberg, Ljungqvist, & Lu, 2010). This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: A reciprocated history of syndicating activity between a lead VC and a potential partner positively moderates the value of experience as a signal, and increases the likelihood of collaboration with the lead VC.

Returning to hypothesis 1, one may ask whether the effect of experience accumulates over time or whether experience in the VC business is subject to rather fast obsolescence, meaning that it has to be renewed by recurring activities in the VC market. Since the VC market deals with innovative business proposals, one could argue that experience accu-mulated years ago may not be worth so much.

differentiation from competitors and prevents the erosion of previously signaled informa-tion (Janney & Folta, 2003).

Hypothesis 4: The frequency of signaling activities positively moderates the effect of signaling strength and increases the likelihood of collaboration with a given lead VC.

Another difficulty VCs face when signaling in uncertain and ambiguous environments is that the decision to syndicate is contingent on the underlying venture. VC financing takes place in emerging and knowledge-intensive industries where the value of the funded projects is highly uncertain and future payoffs are distant. The difficulty of disentangling the contribution of individual activities gives substantial leeway to the entrepreneur. Hence, the characteristics of the financed firm and the corresponding uncertainty could erode the value of a signal by creating noise so that the underlying message of VC ability becomes less evident in earlier rounds. Among other things, a coherent view of signaling therefore needs to take into account the value of signals conditional on venture-level characteristics. VCs usually fund ventures in several financing rounds or stages. The need for additional partner skills is anticipated to be greater in later stages of an investment than in earlier stages. This is mainly due to the fact that more mature firms funded already have an established management structure and market position (Brander et al., 2002; Bygrave, 1987; Bygrave & Timmons, 1992; Lockett & Wright, 1999). Consequently, the advice becomes more specific and context dependent in later rounds, while it is rather general (i.e., it addresses basic management topics) in earlier rounds. Research suggests that VC financing goes hand in hand with institutionalizing human resource management (Hell-mann & Puri, 2002), development of the accounting system allowing for more frequent monitoring (Mitchell, Reid, & Terry, 1997), or internationalization strategies (Mäkelä & Maula, 2005). Arguably, all of these activities become more important in later stages. With every round, the ambiguity and uncertainty of the project decreases. This allows for improved judgment about the managerial advice needed to support the funded firm (Lerner, 1994).

Of course, partners contribute financial resources in every round. Yet as argued earlier the need to add specific knowledge and expertise grows over time. Consistent with this argument, during initial rounds of funding, empirical evidence highlights the role of risk sharing among the VCs involved in a syndicate (Manigart et al., 2005). The value of signals provided could be lower in early rounds, as lead investors will simply be looking for potential partners to share the financial burden, but not necessarily for characteristics proxying quality and ability. Although information is provided and available in the VC network, lead VCs possibly do not look for these characteristics. Signals sent, alone and in combination, only have explanatory power when receivers are actively looking for these signals (Lester et al., 2006). Therefore, the value of the signals is context specific and varies across the different financing stages of VC investing.

Hypothesis 5: As the stage of development of the portfolio firms advances, the strength of the signals emitted rises and increases the likelihood of collaboration with a given lead VC.

Data and Methods

Dataset and Summary Statistics

The sample consists of 2,373 venture capital transactions in Germany within the period of 1995–2005. The number of total financing events (2,373) comprises capital injections from 447 VCs that are made over different stages (start-up, early stage, and late stage) into 964 firms. The focus on the underlying German data has the advantage that we can study VC decision making with respect to partner selection from the inception of Germany’s Neuer Markt, the growth stock segment at the Frankfurt Stock Exchange in 1997, and up to 300 firms that were taken public until 2000, and a paralleling increase in VC investments, until the closure of the Neuer Markt in 2003 and a corresponding decline in VC transactions (von Kalckreuth & Silbermann, 2010). Given the growing focus of investment into these high-risk ventures and a lack of comparable investment histories (unlike in more established markets in other countries), the task of disentangling the role of signals (alone and in combination) is not obscured by longer lasting networks of VC investments, as evidenced by the work of Hochberg et al. (2007, 2010). Hence, being able to signal ability and making use of multiple signals might be more important in environments prone to uncertainty about market participants. And notwithstanding differences between the U.S. VC market and the ones in Germany and Europe as a whole, it is interesting to note that the study by Bottazzi, Da Rin, and Hellmann (2004) covering the years 1998–2001 (which are included in our sample) found that European VC firms were “increasingly emulating U.S. investment practices” and had established links to the United States; furthermore, over a third of European VC had worked in the United States before. Therefore, the results of our study are likely to be relevant also for VC markets beyond Germany.

The transactions were compiled by using public sources and the Thomson Venture Economics (TVE) Database. On average, a funded firm goes through 2.2 rounds of financing. We identify the involved parties in each transaction and the corresponding information on the VCs along with the funded firms. The result is a deal survey exhib-iting who funded a new company and who was joined by which partner. Moreover, we collect information about each financing round to infer which VC made an investment into a target firm at which point in time. In addition we supplement the database with information regarding the VCs and the funded firms, along with information specific to each deal. The analysis is carried out on the basis of investment rounds as indicated by TVE.5

To calculate measures of investment experience acquired by the VCs, we include information on the industries that the funded firms are active in. This also makes it

possible to analyze the acquisition of resources motive by considering the industry of the underlying transaction and the knowledge acquired by the VCs in previous transactions. Based on information from TVE, we identify the industry of a particular venture by applying the Venture Economics Industry Classification (VEIC), a Venture Economics proprietary industry classification scheme. To draw more distinct conclusions, we split the industries further, which results in finer industry clusters. For example, we divide the medical/health classification into two separate categories. In addition, we split the indus-trial sector into indusindus-trial products (such as chemicals and indusindus-trial equipment) and industrial services (such as transportation, logistics, and manufacturing services). A cat-egory for Internet firms is introduced to cope with the particularities of investments into New Economy firms over the period. Groupings have been made based on VEIC level 1 codes. Firms that were solely focusing on the Internet to sell and market products were included in the separate Internet/e-commerce category.

Partner Selection Into the Syndicate as the Unit of Analysis

A syndicate is usually defined as a group of VCs that jointly invest in a certain firm. We look at VCs that invested in the same company simultaneously (within the same round) and in different rounds, thus employing a wider definition of a syndicate. We are less concerned whether VCs invested in the same round, as VC relationships are built by formal interaction (such as board meetings) as well as by informal interaction (Brander et al., 2002; Gompers & Lerner, 2002; Manigart et al., 2005). Thus, previous interactions can yield insights into the decision patterns. Accordingly, a VC who invested in the first round interacts with an investor who joins the syndicate in a subsequent round. The unit of analysis is each accepted invitation of a partner to form a new syndicate or expand an existing syndicate further. Rather than focusing on the dyad level alone, we analyze which partner VC was chosen by the lead investor at which point in time.6Hence, we employ

a methodology that shares many features with a case–control setup. This design is beneficial, as selection among potential VC partners is relatively rare. Units of analysis are selected based on outcomes and not hypothesized relationships (Pennings & Harianto, 1992). By studying the signaling behavior of potential partners relative to each other, we place our analysis into the wider context of signaling models, in which the costs of the signal are borne by higher quality firms at the expense of lower quality firms. Hence, setting oneself apart from competitors signals ability. Accordingly, we need to study signaling behavior vis-à-vis the universe of potential partners to draw inferences (Connelly et al., 2010; Stiglitz, 2002).

In order to cover the dynamics of partner selection in the most comprehensive way, we place no restrictions on the size of the VCs in the sample, thus including both large and small VCs. However, for the list of VCs from which a potential partner is chosen, we restrict the analysis to the most active VCs to ensure variation in the explanatory variables over time (and to avoid problems with autocorrelation). Here we choose a cutoff point of at least 10 deals over the time period of 1995–2005. This reduces the list of partners to 35 among whom the lead investor can choose. In explaining the dynamics of partner selection, we therefore make inferences about the major players within the market, rather than analyzing marginal ones. We do, however, include syndicates formed between major and peripheral VCs. In this case, the dependent variable for the peripheral VC is equal to one, and the entries for the other 35 (more active) VCs are

equal to zero. If one of the more active VCs from the list of likely candidates is chosen, it receives an entry of one, and each nonchosen VC receives an entry of zero for the dependent variable. Our analysis therefore aims at explaining which factors impact the zero/one collaboration variable. We measure experience and contacts on the basis of the VC level rather than for specific funds separately. Underlying this assumption is the argument that ties and experience acquired carry over to a VC’s next funding (Hochberg et al., 2007).

The Role of the Lead Investor

The role in managing and monitoring the underlying investment differs substantially between lead and nonlead investors. Gorman and Sahlman (1989) find that the lead investor spends about 10 times more time on monitoring and managing the investment. In a network where one VC has invited partners to assist in the transaction, it is possible to account for the direction of the relationship. We include a measure of a “leading role” of VCs for each transaction. Hochberg et al. (2007) define the lead investor as the investor who acquires the largest stake in a portfolio company. Megginson and Weiss (1991) and Sorensen (2007) support this definition. As TVE reports only the total amount invested per round and does not distinguish between the sum invested by each VC involved on a stand-alone basis, we proxy for the lead investor(s) using two criteria that have to be fulfilled simultaneously: The maximum number of rounds and the involvement in the initial financing round. The lead investor is defined as the VC that has participated in the maximum number of rounds among all investing VCs and was also involved in the first round of financing. The argument underlying this assumption is the same as in Megginson and Weiss and Sorensen, that the lead investor usually has the largest amount of money at stake and therefore an incentive to take a more active role in managing the syndicate and advising the portfolio company. Thus, we can account for the direction of the ties that are established. A VC that has a leading role within a syndicate thus invites one or more new investors to participate in the deal; those do not have a leading role. Correspondingly, the partnering decision by the lead investor forms the basis of analysis. As the lead investors appear as often as they invited new partners in the data set, we adjust the standard errors for clustering on the lead investor level. We provide a transaction example in the Appendix to illustrate our approach.

Methodology

Each invitation record for a specific transaction includes various VC attributes for the lead investor, as well as for the VCs from which the partner is chosen. The VC attributes are based on the cumulative cooperation behavior until the end of the year prior to the given year. The resulting structure is a cross-section of transactions over time, with varying covariates (such as network status, number of deals, and funds managed) over the years. In order to account for the fact that the sample includes a larger number of nonevents for the dependent variable (indicating all the VCs that have not been chosen to participate in the syndicate), we estimate the coefficients using the rare events logistic adjustments suggested by King and Zeng (2001a).

rare events logistic regressions.7 Additionally, inclusion of dummies for every year

accounts for time effects. All dummies are measured against the year 2000 dummy, which is dropped (to avoid perfect collinearity) from all regressions.

All measures are either calculated as the cumulative number until the end of the year prior to the year in which the deal takes place, or by just using the relevant information from events happening in the year prior to the year in which the deal takes place (the variable description clearly indicates which time horizon was used). This way, issues of causality between the dependent and independent variables are circumvented. For example, the total number of transactions that a VC has made in (or until the end of the year) 2004 is used to explain his partnering decisions in 2005. Hence, a partnering decision in 2005 cannot influence the independent variables in 2004.

Explanatory Variables: Experience

In order to test our hypotheses, we calculate various VC characteristics that act as signals to increase the chances of a potential partner VC to be invited by a given lead VC.

Industry Experience. Hypothesis 1 states that the investment experience of the potential partner VC positively affects the likelihood of collaboration. We compute the total number of transactions within the industry in which the funded firms operates that the lead investor(s) as well as the potential partners have invested in during the year prior to the year in which the deal takes place. To be able to better track the signaling behavior and the quality of the signal, we investigate relative performance, which reveals more infor-mation than absolute performance (Stiglitz, 1975). Accordingly, we calculate the differ-ence between the number of transactions the lead investor and the potential partner engaged in to proxy for additional experience that could be expected from a potential partner. A negative number would therefore indicate that the partner possesses more experience within the given industry than the lead investor.

Explanatory Variables: Direct Relationships

Lead-Invited VC. With respect to hypothesis 2 and the impact of direct previous rela-tionships between the lead investor and the potential partner, we include a measure indicating how often the lead investor previously invited the potential partners (lead-invited VC). Based on the past transactions in which the current lead investor also acted as a lead investor, we count the number of previous collaborations with each potential partner. We hypothesize this measure to positively moderate the effect of investment experience.

Reciprocated Tie (Dummy). We include a measure for reciprocated ties that originate from both sides. Asymmetries in relationship building are detrimental for dyadic stability, and thus we account for a reciprocated tie if the current lead investor has invited the potential partner in the past and if the corresponding partner has also previously invited the current lead VC. That is, the direction of the tie should be bilaterally shared among the partners (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005; Lockett & Wright, 1999; Shane & Cable, 2002). The dummy takes on the value of one if bilaterally shared ties are present and zero otherwise. Again, these measures are calculated cumulatively over the past years and solely over the previous year.

Interaction Terms

Experience¥Lead-Invited VC. To measure the interplay between the signal experience

and the directed tie as a potential amplifier in hypothesis 2, we interact the variables for the direct relationships between VCs and the excess industry experience of potential partners. We use the interaction terms with two separate variables: one based on the contacts during the previous year alone, and a second one using the cumulative informa-tion on partnering behavior, taking into considerainforma-tion the entire past investment horizon. This way, long-term and more immediate effects (informed by hypothesis 4) can be disentangled.

Experience¥Reciprocated Tie. To proxy for the effect of reciprocated ties in

combina-tion with transaccombina-tion-relevant industry experience on the propensity to work collabora-tively on a given deal (presented in hypothesis 3), we interact the reciprocated tie dummy with the excess industry experience of the potential partner. Here we use the presence of a reciprocated tie during the previous year for one variable and over the previous invest-ment horizon for a second variable, and insert them in separate regression specifications.

Type of Financing Round (Dummy). In hypothesis 5, we argue that the relevance of signals depends on which stage the investment is made and when potential partners are to be selected. Hence, while in early rounds VCs aim at spreading risk and therefore are reluctant to search for meaningful signals, the signals become more important in later rounds. TVE gives information about five different stage categories: start-up/seed, early stage, expansion, later stage, and other. Similar to Gompers (1995) who labels the categories for bridge, second, and third stage financing as “late stage” financing, we combine the TVE categories expansion, later stage, and other to form a new category, which we also label “late stage.” As there is no clear distinction between expansion financing, which almost always occurs in later phases, and other financing activities from the “later stage” category, namely bridge financing and special purpose financing, this combination appears to be the most reasonable classification scheme. In the following we split the regressions into separate stages and compare coefficients across the different models, following Hoetker (2007).

Control Variables

the number of funds managed between the lead investor and the potential partner. These measures are calculated using VC fund information from TVE.

Total Deals Previous Year. We control for the activity (and possible investment over-load) of VCs by summing over all transactions a VC was involved in during the pre-vious year. The control variable measures the number of total transactions financed alone and/or as a member of a syndicate. VCs that were involved in a larger number of transactions previously are less inclined to join in on an upcoming transaction due to limitations in management capacity. We include the number of total transactions in all regressions.

Analysis and Results

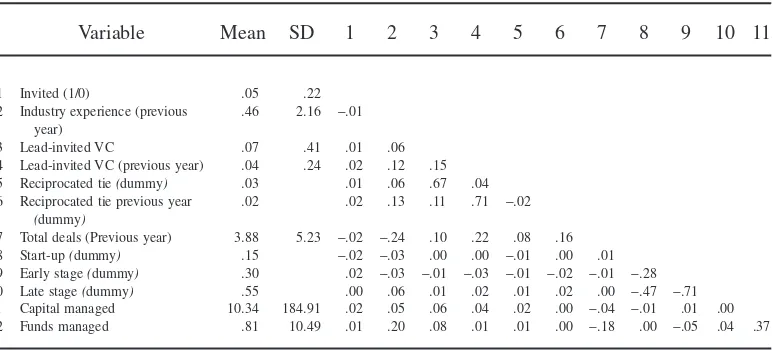

Table 1 reports the summary statistics and the correlation matrix for the independent variables. With respect to the experience within the given industry, one can infer that on average, the lead investors financed about the same number of deals during the previous year as the potential partners did. The measures of previous direct relationships show that over the years, various relationships were formed at differing levels of intensity. Among the 35 potential partners, some .07 ties are present, which indicates that on average, the given lead investor has roughly two ties established over the previous investment horizon and about 1.5 during the previous year alone. Among the relation-ships, there is less than one tie for the previous year where the direction of establishment has been reciprocated with the potential partner and roughly one for the cumulative number of reciprocated ties. The focus of investments is concentrated into late stage investments with around 55%; the early and start-up stage have some 30% and 15%,

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

Variable Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

1 Invited (1/0) .05 .22

2 Industry experience (previous year)

.46 2.16 -.01

3 Lead-invited VC .07 .41 .01 .06

4 Lead-invited VC (previous year) .04 .24 .02 .12 .15 5 Reciprocated tie(dummy) .03 .01 .06 .67 .04 6 Reciprocated tie previous year

(dummy)

.02 .02 .13 .11 .71 -.02

7 Total deals (Previous year) 3.88 5.23 -.02 -.24 .10 .22 .08 .16 8 Start-up(dummy) .15 -.02 -.03 .00 .00 -.01 .00 .01 9 Early stage(dummy) .30 .02 -.03 -.01 -.03 -.01 -.02 -.01 -.28 10 Late stage(dummy) .55 .00 .06 .01 .02 .01 .02 .00 -.47 -.71 11 Capital managed 10.34 184.91 .02 .05 .06 .04 .02 .00 -.04 -.01 .01 .00 12 Funds managed .81 10.49 .01 .20 .08 .01 .01 .00 -.18 .00 -.05 .04 .37

respectively. The correlations among the variables show a few problems of multi-collinearity. Notably, the various tie measures and the interaction terms are correlated. In order to cope with collinear variables, we include them separately into the regressions. In all regressions estimated, the variance inflation factors are, on average, around 1.2– 1.4, thus showing no sign of problems with multicollinearity. Moreover, all condition numbers calculated have values of around 5, and are well below the critical thresholds. It is noteworthy that only when we introduce squared terms into the analysis do the variance inflation factors rise to 3.6, but then they are still well below critical values (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 2005).

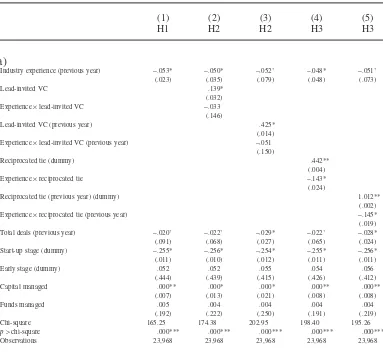

Table 2a presents the regression output using the industry experience measure; it includes only transactions undertaken within the year prior to the year in which a deal takes place. To contrast these results, Table 2b uses cumulative industry experience as a measure of all transactions undertaken prior to that year. Using these two measures, we can disentangle current effects from long-term signaling behavior. The results support

Table 2

Rare Events Logit Regression Using Robust Standard Errors

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

H1 H2 H2 H3 H3

(a)

Industry experience (previous year) -.053* -.050* -.052† -.048* -.051†

(.023) (.035) (.079) (.048) (.073) Experience¥lead-invited VC (previous year) -.051

(.150)

Experience¥reciprocated tie (previous year) -.145*

(.019) Total deals (previous year) -.020† -.022† -.029* -.022† -.028*

(.091) (.068) (.027) (.065) (.024)

Start-up stage (dummy) -.255* -.256* -.254* -.255* -.256*

(.011) (.010) (.012) (.011) (.011)

Early stage (dummy) .052 .052 .055 .054 .056

(.444) (.439) (.415) (.426) (.412)

Capital managed .000** .000* .000* .000** .000**

(.007) (.013) (.021) (.008) (.008)

Funds managed .005 .004 .004 .004 .004

(.192) (.222) (.250) (.191) (.219)

Chi-square 165.25 174.38 202.95 198.40 195.26

p>chi-square .000*** .000*** .000*** .000*** .000***

hypothesis 1, that getting access to new knowledge and resources, as measured by the excess industry experience of potential partners, plays a significant role in explaining the partnering decision in VC syndicates. The coefficient associated with the difference between the number of transactions of the lead investor (within the industry of the Table 2

Continued

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

H1 H2 H2 H3 H3

(b)

Industry experience .005 .008 .006 .010† .007

(.368) (.154) (.310) (.086) (.296) Experience¥lead-invited VC (previous year) -.031* (.034)

Experience¥reciprocated tie (previous year) -.069*

(.027)

Total deals (previous year) -.011 -.012 -.017 -.012 -.016

(.370) (.324) (.169) (.321) (.165)

Start-up stage -.241* -.241* -.241* -.238* -.245*

(.018) (.017) (.018) (.019) (.018)

Early stage .061 .060 .064 .061 .064

(.368) (.372) (.345) (.365) (.350)

Capital managed .000** .000* .000* .000* .000**

(.009) (.013) (.021) (.010) (.009)

Funds managed .002 .002 .002 .002 .002

(.462) (.586) (.547) (.554) (.511)

Chi-square 143.63 147.71 170.17 164.28 176.98

p>chi-square .000*** .000*** .000*** .000*** .000***

Observations 23,968 23,968 23,968 23,968 23,968

†p

<.1; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Notes: Marginal effects. Table 2a presents the results for the regressions using the rare events logistic methodology suggested in King and Zeng (2001a) to account for the fact that the sample includes a larger number of nonevents for the dependent variable (indicating all the VCs that have not been chosen to participate in the syndicate). The first line for each independent variable indicates that the coefficient and the second line shows the correspondingp-values. Standard errors have been adjusted for clustering at the lead investor level. The industry experience measure includes only transactions undertaken within the year prior to the year in which a given deal takes place. Table 2b presents the results for the regressions using the rare events logistic methodology suggested in King and Zeng (2001a) to account for the fact that the sample includes a larger number of nonevents for the dependent variable (indicating all the VCs that have not been chosen to participate in the syndicate). The first line for each independent variable indicates the coefficient and the second line shows the correspondingp-values. Standard errors have been adjusted for clustering at the lead investor level. The industry experience measure includes all transactions undertaken prior to the year in which a given deal takes place.

funded firm) and the potential partner is positive and highly significant across all speci-fications estimated.8 We also test the absolute experience (in contrast to the relative

experience) and find the same effects as for the relative measures. The results shown in Table 2b report that the cumulative investment experience is not significant at conven-tional levels and hence has no impact on partnering behavior, supporting the arguments in hypothesis 4 that experience becomes obsolete over time and signals have to be renewed continuously. Only experience that is more immediate increases the chances of collaboration. In unreported regressions, we also used a measure comprising only unsuccessful transactions (deals in which the portfolio company went bankrupt). Here, all coefficients reported turn insignificant. These results confirm hypothesis 1 that addi-tional experience is a predictor of collaboration among VCs. However, experience only carries signaling value when the underlying deals turn out successful, providing evi-dence that it is not that experience in general is the driving force, but that experience has to be relevant (such as previous successful transactions) for the lead VC looking for potential partners.9

Turning to hypothesis 2, Table 2a suggests that past direct relationships affect the likelihood of participation in a syndicate positively. However, the interaction is not significant at conventional levels for neither the cumulative number of directed ties, nor for the previous year variables. From Table 2b, we can infer that direct ties increase the value of the signal when the underling base signal is cumulative industry experi-ence (which is insignificant as a single variable). The coefficient associated with the interaction term is significant at the 5% level for both interactions terms. Hence, there appears to be some, albeit weak, evidence supporting the arguments advanced in hypothesis 2.

Turning to hypothesis 3 and the influence of reciprocated ties on collaboration patterns, we find that both interaction terms are positive and highly significant. In Table 2a we can infer that reciprocation acts as a strong signal in conveying information to lead VCs inviting potential partners, while the interaction with direct ties remains insignificant. Table 2b reports the robustness of the reciprocation effect, where both interaction terms are significant at the 5% level. Hence, there is strong evidence supporting hypothesis 3, that the multitude of signals is more important than the pure presence of experience as a sole signal. Reciprocation presents a stronger signal than directed ties alone and positively moderates the effects of the previous year and cumulative investment experience. Con-cerning our argumentation in hypothesis 4, the tables show that only industry experience

8. We also include yearly dummies in all regressions that are, for reasons of brevity, not reported in Tables 2–4. The dummies for all the years 1996 and 2003 are significantly different from the omitted 2000 dummy and exhibit a negative sign. This indicates weak evidence that in the years where fewer transactions take place, the chances of being invited are lower.

as a base signal is relevant for collaboration when stemming from the previous year; the measures for reciprocated ties and direct ties are all statistically insignificant. Hence, there is support for hypothesis 4 only with respect to the base signal industry experience.10In

10. We also use a measure of reciprocity following the methodology of Chung, Singh, and Lee (2000), which shows the same effect. Additionally, we included a squared term for the number of previous directed collaborations between the current lead VC and the potential partner. The squared term is negative and significant for the cumulative number of collaborations, indicating an inverse U-shaped effect, although the coefficient is only significant at the 10% level. One could speculate that too many joint deals within a short

Figure 2

Interaction Effect Experience¥Lead-Invited Venture Capitalist (VC) (Model 2)

Figure 3

period of time lead to a substantial knowledge transfer, so that a partner risks losing the competitive advantage that gave rise to his or her being invited in the first place. This area clearly deserves more attention. Results are not tabulated but are available upon request from the authors.

Figure 4

Interaction Effect Experience¥Lead-Invited Venture Capitalist (VC) Previous Year (Model 3)

Figure 5

unreported regression, we also included an interaction term using the number of un-successful transactions together with direct ties and reciprocated ties. Interestingly, the interaction terms using unsuccessful experience and direct ties turn insignificant. However, the interaction terms using the reciprocated ties remain highly significant and negative. This indicates that the only way to overcome the erosion of signals is to maintain Figure 6

Interaction Effect Experience¥Reciprocated Tie (Model 4)

Figure 7

reciprocated ties with the current lead VC. Hence, we find again strong support for our hypothesis 3, suggesting that a reciprocal history of syndicating activity between the lead VC and a potential partner positively moderates the value of experience as a signal and increases the likelihood of collaboration with the given lead VC.

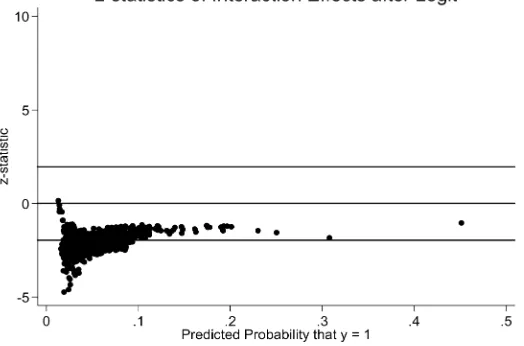

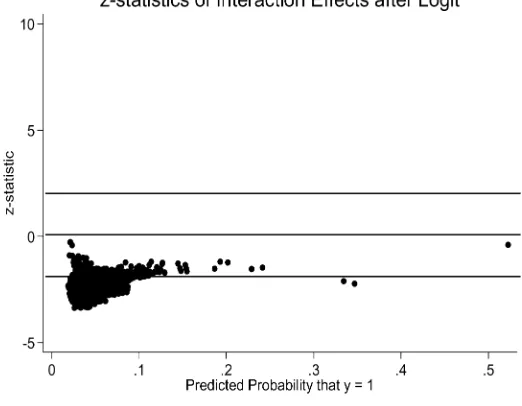

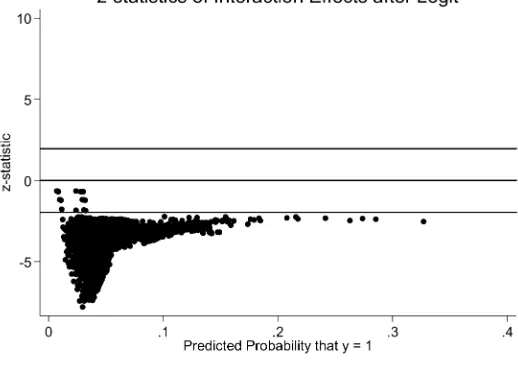

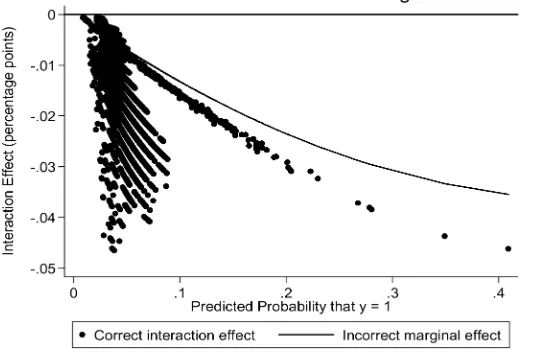

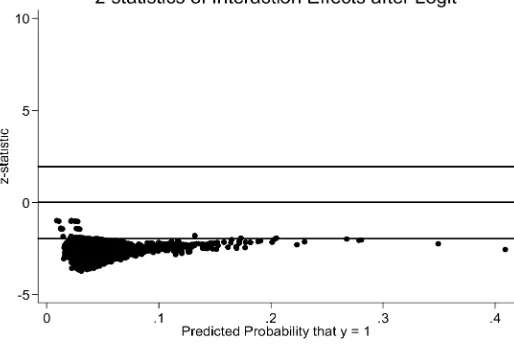

Ai and Norton (2003) and Hoetker (2007) document that the sign of the interaction in logit models merely suffices to draw ultimate conclusions about the effect of the interaction on the dependent variable. They argue that depending on the covariates, the sign of the interaction term might vary. We follow their proposed methodology to calculate the magnitude and standard errors of the estimates for the interaction term in a logit-regression specification, and depict the results along the entire range of values in Figures 1–8. We make use of the results in Table 2a, given the stronger effects of more recent investment experience and the insignificance of the baseline (cumulative) invest-ment experience measure in Table 2b. We report two sets of figures for each interaction term in Models 2–5 in Table 2a. The first figure plots the interaction term in percentage points against the predicted probability (and the incorrect marginal effect), while the second figure reports the z-statistics for the corresponding interaction term. Calculations are done in accordance with formulas provided in Ai and Norton.

When we look at the interaction effect using the measures provided in Ai and Norton (2003), Figures 2–5 document a widely varying pattern for the interaction term using direct ties. Both effects are found to be negative, even when we split the sample into subsamples with the greater experience of the lead on the one hand and the lesser experience of the potential partner on the other hand, we find the same pattern. However, the levels of significance (the z-scores) vary heavily.11 While for some values of the

11. Industry experience has a significant negative effect only when the partner possesses more experience, not when the lead investor has more experience. However, focusing only on a sample where the potential partner has less experience (or more experience) is relatively meaningless, as we want to explicitly model the trade-off with respect to choosing among different partners and consequently different levels of experience or the lack

Figure 8

interaction effect significant results can be found, the overall pattern suggests that the coefficients are not robustly related to the partnering decisions. Hence, this suggests no evidence for our hypothesis 2.

Concerning the interaction of reciprocated ties and experience to proxy for a stronger signal comprising experience and the ability to generate deal flow (hypothesis 3), Table 2a and 2b show that the effect using the entire time elapsed, and only the previous year to calculate reciprocated ties is negative and statistically significant. In addition, calculating the interaction effect of the continuous experience measure and the reciprocated tie dummy indicates that the effect is negative for both measures and statistically significant (as indicated by the z-score plot in Figures 6–9) over almost the entire range of outcomes. Hence, there is strong evidence that the combination of experience and deal flow consti-tutes a strong predictor of collaboration and that the multitude of signals matters in explaining interaction patterns. In sum, we find evidence strongly supporting hypothesis 3, that being able and willing to reciprocate and provide access to deal flow is a crucial and important signal for future cooperation (Figure 9).

To test hypothesis 5, we split the sample into stages of development (e.g., start-up, early stage, and later stage) to see whether the impact of signals differs across stages (Sorenson & Stuart, 2008). For a comparison across groups to be meaningful, each group must have the same level of unobserved variation, i.e., variation in outcomes beyond the error term. Allison (1999) documents that if that is not the case, information drawn from group comparisons could be misleading, and differences across coefficients might simply reflect differences in samples caused by unobserved variations and need not be related to

thereof. Hence, while one needs to interpret the results with some caution, the overall interpretation (impres-sion) is that partners are chosen based on additional experience. Moreover, having less experience than the lead is not more detrimental than having the same level of experience; neither provides any additional experience that is important for the lead investor. Given the strong presence of nonevents in the data set, the predicted probabilities are concentrated below the .2 level.

Figure 9

the explanatory variables chosen. We estimate the models separately for each investment stage following Hoetker (2007) to allow for inferences across groups.12

From Tables 3 and 4, one can infer that the stage of development of the portfolio firm positively moderates the value of signals emitted, and signal strength increases the likelihood of collaboration. Signals are less sought after in early stages, while VCs in later stages place a stronger emphasis on signals and combinations of signals. Excess industry experience of the potential partner is not statistically significant at conventional levels in any of the start-up stage regression specifications. However, the coefficient is negative and significant for the early stage samples. Accordingly, experience signals ability for early stage investments but not for start-up investments. In addition, Tables 3 and 4 show that none of the other interaction terms is significant for the corresponding regression specifications within the start-up stage. Only the number of total deals, as a proxy for the investment intensity of the lead and the difference in the number of funds managed, are significant. In sum, the results favor risk-spreading arguments and point toward the irrelevance of signals in start-up stages. Accordingly, when syndicating in start-up stages, lead VCs aim at spreading risk rather than searching for partners to create value added for entrepreneurial firms.

When turning to the interaction terms of directed ties and reciprocated ties with excess investment experience in early and later stages, the interaction terms of directed ties and experience are significant in the late stage only. The results suggest only weak support or no support for the idea that direct ties are important for partner selection across the different stages. Both variables are only marginally significant. In contrast, reciprocated ties and the interaction with experience are highly significant in the early and later stage phase. To test whether the size of the coefficients differs across the early and late stage for reciprocated ties (columns 2 and 3 in Table 4), we estimate a combined model for later and early stage investments and subsequently test whether the interaction term for an early stage dummy and reciprocated ties is significantly different from zero. Here we model the effect that is likely to differ across groups as an interaction term and test whether this term is significant when added to the baseline model. The significance of this interaction term then allows inferences about whether coefficients differ across groups (Allison, 1999; Wooldridge, 2008). We also extend this methodology to the effect of reciprocated ties from the previous year only. The results of a likelihood ratio test show that the coefficients for reciprocated ties (Models 2 and 3 in Table 4) do not significantly differ between early stage and later stage investments (likelihood ratio [LR]: .77,p=not significant [n.s.]). The same effect can be found for reciprocated ties for the previous year only (Models 5 and 6 in Table 4). Again, the difference between coefficients is not significant (LR: 1.08,p=n.s.). Hence, we can conclude that the effect of reciprocated ties on the likelihood of collaboration differs between the start-up stage and the later stages (comprising both early and late stage investments). Thus, the results strongly support hypothesis 5 within early and later stages in comparison with the start-up stage. Signals are less sought after in early stages, while VCs in later stages place a stronger emphasis

Table 3

Table 2a Regressions Split Into Stages—Models 1, 2, and 3

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9)

Start-up

Early stage

Later

stage Start-up

Early stage

Later

stage Start-up

Early stage

Later stage

Industry experience (previous year) -.035 -.105** -.042 -.040 -.099* -.036 -.017 -.112* -.040 (.206) (.008) (.119) (.155) (.011) (.227) (.629) (.022) (.208)

Lead-invited VC .143 .070 .194*

(.486) (.402) (.016) Experience¥lead-invited VC .021 -.079 -.053* (.825) (.365) (.045)

Lead-invited VC (previous year) -.030 .503† .558**

(.917) (.087) (.002) Experience¥lead-invited VC (previous year) -.104 -.005 -.071*

(.369) (.946) (.027) Total deals (previous year) .058** -.042† -.035† .055** -.043† -.039† .059** -.046† -.051*

(.001) (.063) (.083) (.003) (.065) (.057) (.003) (.053) (.025) Capital managed .000 .000 .000* .000 .000 .000* .000 .000 .000*

(.302) (.882) (.010) (.321) (.921) (.020) (.293) (.997) (.028) Funds managed .029*** .005 -.001 .028*** .004 -.002 .028*** .005 -.002

(.000) (.292) (.819) (.000) (.302) (.758) (.000) (.296) (.651) Chi-square 21.87 18.20 6.75 23.47 7.35 7.75 10.33 10.46 12.87

p>chi-square .000*** .077† .080† .000*** .201 .171 .016* .063† .025*

Observations 3,750 7,107 13,111 3,750 7,107 13,111 3,750 7,107 13,111

†p

<.1; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Notes: Marginal effects. Table 3 documents the logistic regressions carried out in Models 1, 2, and 3 in Table 2a split into stages of development. Comparisons among coefficients are made in accordance with Hoetker (2007).

659

May

,

on signals and a combination thereof. However, the strength does not differ further between these two stages.

In the start-up stage, there appears to be no signaling value for multiple signals. In the early stage, investments experience alone appears to be a sufficient predictor. However, multiple signals carry more weight in later stage investments. This supports the view that financial motives drive the need to spread risks among VCs engaged in seed financing and that potential value-added motives become involved when firms are at a later stage of investment (Manigart et al., 2005). Accordingly, in later stages, the relevance of signals and the necessity for the creation of value-added advice both help explain VC syndication patterns (Brander et al., 2002; Manigart et al.).

We test for the strength of the impact that each explanatory variable has on the chances of collaboration. Inferences about the change in the likelihood of collaboration as a reaction to a change in one of the explanatory variables are based on the relative risk ratio suggested in King and Zeng (2001b). A one standard deviation increase in excess investment by the potential partner increases the chances for collaboration by 10%. An additional direct tie (cumulative) increases the chances by 13%, while a more recent direct tie increases the chances by 45%. An additional cumulative reciprocated tie raises the chances of being invited by 50%, and a recently reciprocated tie more than doubles the likelihood of collaboration. Again, these results support the economic magnitude of creating signals more frequently.

Table 4

Table 2a Regressions Split Into Stages—Model 4 and 5

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Industry experience (previous year) -.036 -.102** -.034 -.027 -.114* -.036 (.197) (.004) (.275) (.410) (.019) (.229)

Reciprocated tie .335 .590* .481**

(.486) (.020) (.006) Experience¥reciprocated tie .006 -.124 -.204* (.978) (.582) (.015)

Reciprocated tie (previous year) .120 .937* 1.301**

(.817) (.013) (.002) Experience¥reciprocated tie (previous year) -.066 -.002 -.205**

(.579) (.992) (.002) Total deals (previous year) .057** -.045* -.038† .058** -.047* -.049* (.001) (.047) (.059) (.002) (.047) (.029)

Capital managed .000 .000 .000* .000 .000 .000*

(.319) (.895) (.011) (.301) (.895) (.017)

Funds managed .029*** .004 -.001 .028*** .004 -.002

(.000) (.404) (.807) (.000) (.298) (.729)

Chi-square .61 23.35 36.90 33.19 35.21 56.02

p>chi-square .735 .037* .000*** .000*** .000*** .000***

Observations 3,750 7,107 13,111 3,750 7,107 13,111

†p

<.1; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Discussion

When investing jointly into portfolio firms, partner VCs are mutually dependent on each other. Consequently, the decision of whom to invite to participate in VC trans-actions lies at the heart of understanding why syndication adds value to the funded firm. Analyzing the decisive factors in partner-selection processes therefore represents a prom-ising way to get an understanding of why and how syndication adds value to a VC-backed firm.

In our work, we show that different combinations of signals can spur cooperation between VCs. While industry experience generally signals competence and increases the chances to be invited, the combination of industry experience and previously established ties is associated with a higher probability of cooperation. For the whole sample, we find that industry experience represents a valuable signal to infer the ability of potential partner VCs (although it does not hold for all stages; see later). Given that syndication offers access to additional expertise that the lead VC may lack, it is intuitive that experience matters in the partnering decision. More experience simply signals higher ability. Our results also document that the ability to generate deal flow and the willingness to subse-quently share with partners act as strong signals for a lead investor searching for coin-vestors. Interestingly, and contrary to one of our hypotheses, directed ties do not increase the strength of the signal experience, yet reciprocated ties do so.

More importantly, we find that combining signals of quality and intent—industry experience and reciprocation—strongly increases the probability of cooperation. Accord-ingly, signaling the willingness to invite potential partners back in the future and docu-menting one’s own ability to generate deal flow represents the strongest signal among potential partners. Seeing a partner in different roles, both as lead VC and as invited partner, helps to assess the partner’s ability better. Another possible explanation could be that reciprocated ties mirror positive intent or are interpreted as evidence for satisfying collaborations in the past. Apparently, working together in a deal or sharing a deal flow generates a useful signal about the partner’s ability. In light of the high returns for well-networked VCs, enhancing one’s network position could present a vital strategic consideration for an incumbent VC (Hochberg et al., 2007, 2010). As our results indicate, being able to syndicate with a larger number of new partners substantially improves a VC’s position, increasing the VC’s likelihood of being invited to other profitable deals in the future. In this way, repeated relationships might transfer expectations about the partner’s behavior and possession of competencies from a previous deal to the new transaction. Consequently, partners regard a transaction as a situation of mutual gain.

Yet, we also show how the value of signals erodes over time; that is, signals from the previous year carry more informational value than signals from more distant years. This means that VCs must invest repeatedly in generating a deal flow to sustain their advantage over other VCs. A possible reason could be the young age of VC firms in our study, so that for them, there is no established history of maintaining certain ability over time. In such a situation, turnover may be associated with increased uncertainty about ability. To reduce this uncertainty, a lead VC places more value on a recent signal—the probability of again working with the people (and not just the same firm) that generated that signal is higher than the one for signals from the more distant past. An alternative explanation would be that knowledge rather quickly obsolesces in innovative industries. Experience acquired through deals dating back a longer time does not represent a reliable indicator of a sufficiently high ability to master future deals.