EXAMINING DIFFERENTIAL OFFICER EFFECTS

IN THE MINNEAPOLIS DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

EXPERIMENT

Patrick R. Gartin

University of Nebraska at OmahaINTRODUCTION

It has now been a decade since research results from the much-cited Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment (Sherman and Berk, 1984a) were first published. The major reported finding from this study, most often summarized as “arrest works best” as a specific deterrent for spouse abusers, has been disseminated widely and is believed by many to be at least partially responsible for changing the way our nation’s police respond to instances of misdemeanor domestic assault (e.g. see Binder and Meeker, 1988; Cohn and Sherman, 1987; Gartin, 1992; Lempert, 1989; Sherman and Cohn, 1986, 1989). While a number of other factors were certainly also at work (see Sherman and Cohn, 1989), the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment (referred to hereafter as the MDVE) appears to have had quite a significant impact in helping to turn the tide toward a nationwide pro-arrest sentiment regarding domestic violence. In doing so, it has arguably become one of the most highly influential pieces of criminological policy research in recent times

Sherman and Cohn (1989) have engaged in a debate regarding the appropriateness of the level to which the findings from the MDVE were publicized and promoted. Whereas Lempert has suggested that the findings from the MDVE were “prematurely and unduly publicized” (1984:509), Sherman and Cohn (1989) have argued that high levels of publicity can serve to speed up the process by which research studies are replicated.

Essentially, the concern expressed by Binder and Meeker (1988) and Lempert (1984, 1989) is that the findings of the MDVE moved too quickly from print to policy, rather than waiting for replications to address questions regarding the external validity of the study. The fear of such critics is that a policy that may have worked in Minneapolis may not work equally well, or at all, elsewhere. While this issue of external validity is certainly a critical one, it is arguably of secondary importance to that of internal validity. As is the case with all research, there is the danger that threats to internal validity could have resulted in erroneous conclusions in the MDVE. It is suggested here, therefore, that the question that should more appropriately be addressed first is that of whether or not arresting the suspect actually did work best in Minneapolis as a specific deterrent for misdemeanor spouse abuse.

Although it was designed originally as a controlled randomized experiment, with the express purpose of guarding against the many potential threats to internal validity, a recent reanalysis and methodological critique of the MDVE (Gartin, 1992) suggests that perhaps the findings from the study may not be as clear cut as they were originally thought to be. This critique raises several issues related to the design, implementation and evaluation of the MDVE that may affect how the findings from the study are eventually interpreted; among these are, the way in which recidivism was conceptualized and operationalized in the study, the analytic approach that was used in comparing treatment groups, and the differential participation rate among the officers involved with the study (Gartin, 1992).

the experimental protocol, any previous analyses of treatment effects in the MDVE could be tainted by differential officer effects.

This paper seeks to address the issue of differential officer effects in the MDVE by distinguishing between high rate officers (those who generated ten or more cases) and low rate officers (those who turned in less than ten cases). First, however, a brief review of the MDVE is provided below in order to set the stage for the analyses that follow.

A BRIEF REVIEW OF THE MINNEAPOLIS

EXPERIMENT

Described as “the first scientifically controlled test of the effects of arrest for any crime” (Sherman and Berk, 1984a:1), the MDVE employed a randomized experimental research design in two of Minneapolis’ police precincts as a means of examining differences in recidivism rates across treatment groups of selected domestic violence suspects. By doing so, the original investigators hoped to determine whether or not, and if so to what degree, there were any specific deterrent effects of arrest for misdemeanor domestic assaulters.

Beginning on March 17, 1981, all cases of misdemeanor domestic assault where both the suspect and victim were present when the police arrived were randomly assigned to receive one of three distinct police responses. The three experimental treatments were defined as

(1) arrest, where the suspect was taken to jail; (2) advise, which could include mediation; and

(3) separate, where the offender was ordered from the premises. The experimental criteria were in effect until August 1, 1982, and 330 cases were generated during the course of the study (Sherman and Berk, 1984b).

(1984b:269), thus leading them to “favor a presumption of arrest” (1984b:270). As was noted earlier, the message from this that apparently reached policy makers’ ears was simply that “arrest works best,” although Sherman and Berk (1984b) were careful to qualify their support for pro-arrest policies to include only those jurisdictions that processed domestic assult cases in a manner similar to that of Minneapolis, and only those cases where there was no clear indication that an arrest would be counterproductive.

ASSESSING THE POTENTIAL FOR OFFICER

EFFECTS

Sherman and Berk were themselves the first to suggest that officer effects may be a problem in the MDVE, acknowledging that “a few officers accounted for a disproportionate number of the cases” (1984b:269). In fact, “three of the original officers produced almost 28 percent of the cases” (Sherman and Berk, 1984b:264), and even though Berk and Sherman assert that all of the “officers were volunteers who had committed themselves to the study for over a year” (1985:39), participation on the part of most officers was poor at best.

Originally, all of the 34 officers who were assigned to the city’s two precincts with the highest rates of domestic incidents were recruited to help with the project, with all but one agreeing to participate. However, after a few months it became obvious that only about half of these original officers were turning in cases, so the decision was made to add 18 additional officers to the study (Sherman and Berk, 1984b:264).

Of these 51 officers involved with the MDVE, nine (17.65%) turned in no experimental cases at all during the year and a half that the study was under way. Of those officers who did contribute cases, more than a fourth (28.57%) turned in only one or two; thus, quite a large proportion of the recruited officers had virtually no involvement at all with the study.

What we have been interpreting, therefore, as results from different intervention strategies could reflect the special abilities of certain officers to make arrest particularly effective relative to the other treatments. For example, these officers may have been less skilled in mediation techniques (1984b:269).

To address this concern regarding the construct validity of the treatments, Sherman and Berk report re-estimating their models for the prevalence of recidivism, “including an interaction effect to capture the special contributions” of the high productivity officers (1984b:269). Although no definition is provided as to which officers were considered highly productive, Sherman and Berk conclude that “the new variable was not statistically significant, and the treatment effect for arrest remained” (1984b:269).

COMPARING HIGH RATE AND LOW RATE

OFFICERS

Since our goal is to determine whether or not officers who turned in experimental cases at a high rate were also different in other respects from the rest of the officers in the study, we need to first define who the high rate officers are. As was indicated above, 42 police officers generated cases for the MDVE. If each officer was to have participated equally in the study, while on similar beats and shifts, one would expect a mean contribution of slightly less than eight (7.86) experimental cases per officer. For our purposes here, high rate officers have been identified as those who turned in ten or more cases; although somewhat arbitrary, this cutting point was selected because it represents a contribution that is 25 percent greater than the expected mean of eight cases per officer.

We find that a dozen officers fitting this definition handled 200 of the experimental cases (110 of which were generated by four of the high rate officers with 20 or more cases). The remaining 30 officers, referred to hereafter as low rate,1contributed a combined total of 130 experimental

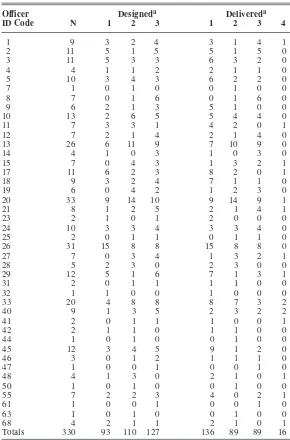

cases. Using this distinction, it can be seen that the 12 high rate officers, representing less than 30 percent of all the contributing officers, turned in more than 60 percent of the cases. Further, the average case contribution of the high rate officers (16.67) is nearly four times that of the low rate officers (4.33). Clearly, therefore, the definition of high rate officers used here differentiates effectively between two disparate groups of officers in terms of their experimental case contributions. Frequencies of case generation for each of the participating officers, broken down by both designed and delivered treatments, are presented in Table 1.

Having identified the high rate officers, we are now able to compare them to the other officers in the MDVE to see if they are different in any way other than on the number of experimental cases that they entered into the study. The only available factors on which to compare the officers, other than the number of cases that they generated, are those which relate to their handling of the cases in terms of how well they followed the experimental protocol. Two comparisons that present themselves could reflect differences between low rate and high rate officers in the degree of protocol deviation:

Table 1

(2) the rate at which the officers entered inappropriate cases into the study.

The first of these comparisons looks at how often officers delivered an experimental treatment that was different to that which had been designated randomly for the case at hand – something that occurred in 72 (21.82%) of the MDVE cases overall. Given that the randomization was by officer, one would expect roughly equivalent proportions of cases deviating from the randomized treatment for all officers, absent of course, from any officer effect. However, as Part A of Table 2 shows, the proportion of cases in which the low rate officers failed to deliver the randomly designed treatment (30.77%) is nearly twice as high as that of the high rate officers (16.00%). Without a doubt, the low rate officers were associated with randomization implementation failure at a significantly higher rate than were the high rate officers.

A second way to compare these two groups of officers on the degree to which they conformed with the experimental criteria, is to look at how closely they followed the rules pertaining to which cases should be entered into the study. Since there exists no measure of cases that may

Table 2

DEVIATIONS FROMDESIGN BYLOWRATE ANDHIGHRATEOFFICERSa

Officer Type No Yes Total

A. Failure to Deliver Treatment as Randomly Designed

Treatment Delivered as was Randomly Designed?

Low Rate 40 90 130

High Rate 32 168 200

Total 72 258 330

Chi-squared = 9.228; df = 1; p= 0.002

B. Entering Inappropriate Cases into the Study

Case Appropriately Entered into Study?

Low Rate 11 119 130

High Rate 5 195 200

Total 16 314 330

Chi-squared = 4.846; df = 1; p= 0.028

aHigh rate officers are defined as those who entered ten or more experimental cases into

have been eligible but were not entered into the experiment, we must rely here on those cases that were entered, but subsequently deemed ineligible by the research staff. These would be the 16 cases deleted from the original analysis “primarily because they did not fall within the definition of incidents included in the study” (Berk and Sherman, 1988:71). As the results in Part B of Table 2 clearly indicate, the proportion of the cases contributed by low rate officers that were deemed to be ineligible (8.46%) was significantly greater than the comparable proportion among the high rate officers (2.50%).

The findings presented in Table 2 demonstrate clearly that the 12 high rate officers were following experimental protocol more closely than the low rate officers, both in determining case eligibility and applying treatments as randomly designed. There are a number of possible reasons for these differences. For example, the high rate officers may have been more committed to the study, or simply learned through more practice to follow better the experimental guidelines. It is also possible that the low rate officers may have been lazier, or more resentful of the lack of discretion that the study created for them. Whatever explanation one accepts, the distinction is quite clear; the low rate officers failed to deliver treatments as randomly designed twice as frequently as the high rate officers, and they entered ineligible cases at a rate three times that of their high rate counterparts.

MEASURING TREATMENT EFFECTS USING HIGH

RATE OFFICER CASES

the full sample from the MDVE, the distribution of cases across the randomly assigned treatments within the high rate officer sample is nearly identical,2thus diminishing the possibility of any one treatment being more likely than the others to show an effect.

Another possible method of controlling for any differential officer effects, which would be even more stringent than that described above, would be to analyze only those cases generated by officers who had no randomization implementation failures at all during the course of the study. This approach, however, would drastically reduce our analysis sample to only 79 cases. Even if we included all those officers with a randomization implementation failure rate of as much as 5 percent (n = 17), only 138 cases would remain to be analyzed. I therefore proceed with the analysis of treatment effects using the 200 cases generated by the high rate officers as described above.

Victim Interview Measures

Before assessing the relative impact of the three experimental treatments using the victim interview data, the working definition of recidivism pertaining to these data that was employed by the original investigators (Sherman and Berk, 1984b) is reconsidered. Sherman and Berk describe the victim interview measure by stating that “victims were asked if there had been a repeat incident with the same suspect, broadly defined to include an actual assault, threatened assault, or property damage” (1984b:266). Thus, the original victim interview measure goes far beyond assessing the prevalence of repeated incidents of physical assault. Although Sherman and Berk note that “almost identical results follow from a definition including only a new assault” (1984b:267), no rationale for their expanded definition is presented. Indeed, there seems to be a good argument against such a broad conceptualization.

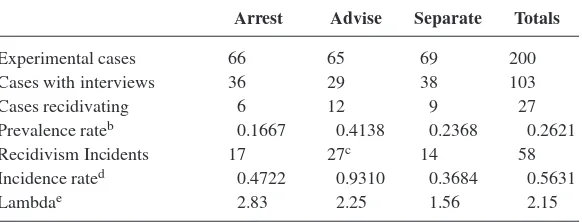

Finally, although Sherman and Berk (1984b) restricted their analyses to comparisons of recidivism prevalence rates, there are variables available in the MDVE victim interview data which allow for the construction of an incidence based measure of recidivism. Using the definitional framework of Blumstein et al.(1986), incidence here refers to a measure of the frequency with which recidivism occurred, whereas prevalence reflects whether or not recidivism occurred at all. Examination of both of these types of measures may allow for a more in depth understanding of the relative effects of the various police strategies in the MDVE. For example, it may be the case that a particular police action reduces the prevalence of recidivism, but yet at the same time increases the mean incidence of violence. In such a scenario, there would be fewer violent people, but more overall violence, thus making it difficult to suggest that the intervention was a “success”. To explore such possibilities, both prevalence and incidence measures of recidivism were derived from the follow up victim interviews for use in the analyses presented in Table 3.

As is indicated in Table 3, there is no overall significant difference, using the traditional p ≤0.05 cutoff, found between the three designed treatments3on either the prevalence or the incidence measures of recidivism developed from the victim interviews. It is also worth noting that there are no significant differences between the treatment groups in terms of the proportion of victims who granted interviews. Also, although there were only a few more than a hundred cases available for these analyses4, it is interesting to point out that while there are fewer suspects recidivating within the arrest treatment than within the others, the incidence rate is highest among the recidivating suspects in the arrest treatment. This pattern would seem to lend some credence to the suggestion made above that prevalence and incidence measures may sometimes give us conflicting results, thereby making it somewhat more difficult to determine the relative “success” of treatments in policy studies such as the MDVE.

Finally, regression models5pertaining to the victim interview

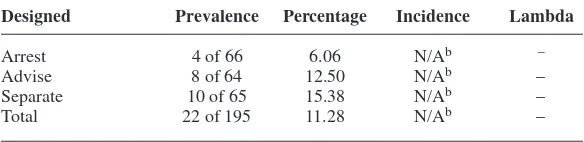

Official Police Measure

As described by Sherman and Berk, the official police measure of recidivism in the MDVE indicated, for each case, whether or not the police generated “a written report on the suspect for domestic violence, either through an offense or an arrest report written by any officer in the department, or through a subsequent report to the project research staff of a randomized (or other) intervention by officers participating in the experiment” (1984b:266). The data available from the MDVE do not include variables which allow for the creation of an incidence based measure of recidivism from the official police records. Thus, the findings presented in Tables 5 and 6 are based on analyses of only the official police prevalence measure as originally constructed by Sherman and Berk (1984b).

The chi squared test reported in Table 5 fails to show a statistically significant difference between the three designed treatments on the prevalence of recidivism as measured by the official police records.

Table 3

RECIDIVISMWITHINSIXMONTHS BYDESIGNEDTREATMENT ASMEASURED BYVICTIMINTERVIEWS FORCASESGENERATED BY

12 HIGHRATEOFFICERSONLYa

Arrest Advise Separate Totals

Experimental cases 66 65 69 200

Cases with interviews 36 29 38 103

Cases recidivating 6 12 9 27

Prevalence rateb 0.1667 0.4138 0.2368 0.2621

Recidivism Incidents 17 27c 14 58

Incidence rated 0.4722 0.9310 0.3684 0.5631

Lambdae 2.83 2.25 1.56 2.15

aRecidivism = a new assault or attempted assault as indicated in the victim interviews bPrevalence of recidivism among cases with interviews.

Chi-squared = 5.271; df = 2; p= 0.072

cOne outlying case generated 10 of these 27 incidents dMean rate of recidivism among cases with interviews.

Bonferroni t-tests show no significant differences

eMean rate of recidivism among those cases recidivating.

Similarly, the probit model presented in Table 6 indicates no differential effects on recidivism across the randomized treatments. It is worth noting, however, that though not statistically significant, the direction of the findings for the prevalence measures shown in Tables 3 and 4 are consistent with the originally reported results in that the arrest treatment has the lowest rate of recidivism of the three randomized treatments.

Table 4

PROBIT ANDTOBITMODELS OFRECIDIVISMWITHINSIXMONTHS BY DESIGNEDTREATMENTASMEASURED BYVICTIMINTERVIEWS FOR

CASESGENERATED BY12 HIGHRATEOFFICERSONLYa

A. Probit Model for Prevalence of Recidivism

Maximum Likelihood Estimates

Log-Likelihood . . . .– 77.914 Restricted (slopes = 0) Log-L . . . .–79.156 Chi-Squared (2) . . . .2.4839 Significance Level . . . .0.28881

Standard

Std Mean Deviations

Variable Coefficient Error T-ratio Prob|t|≥x of X of X

ONEb –1.12434 0.191213 –5.880 0.00000 1.00000 0.00000 DESARRc –0.210840 0.288692 –0.730 0.46519 0.33000 0.47139 DESADVd 0.226423 0.262963 0.861 0.38921 0.32500 0.46955

B. Tobit Model for Incidence of Recidivism

Maximum Likelihood Estimates

Log-Likelihood . . . .– 126.15

Std Mean Std.D.

Variable Coefficient Error T-ratio Prob|t|≥x of X of X

ONEb –5.15081 1.23907 –4.157 0.00003 1.00000 0.00000 DESARRc –0.514996 1.23970 –0.415 0.67783 0.33000 0.47139 DESADVd 1.14529 1.13598 1.008 0.31336 0.32500 0.46955 SIGMA 4.39941 0.717789 6.129 0.00000

aRecidivism = a new assault or attempted assault as indicated in the victim interviews bONE = 1 if designed treatment was separation; 0 = otherwise

Table 5

RECIDIVISMWITHINSIXMONTHS BYDESIGNEDTREATMENTAS MEASURED BYOFFICIALPOLICERECORDS FORCASESGENERATED BY

12 HIGHRATEOFFICERSONLYa

Designed Prevalence Percentage Incidence Lambda

Arrest 4 of 66 6.06 N/Ab –

Advise 8 of 64 12.50 N/Ab –

Separate 10 of 65 15.38 N/Ab –

Total 22 of 195 11.28 N/Ab –

Chi-squared = 2.618; df = 2; p= 0.270 (n= 200)

aRecidivism = presence of an offense or arrest report that indicates a subsequent domestic

incident involving the same suspect and same victim as in the experimental incident

bNot available

Table 6

PROBITMODEL OFRECIDIVISMWITHINSIXMONTHS BYDESIGNED TREATMENTASMEASURED BYOFFICIALPOLICERECORDS FORCASES

GENERATED BY12 HIGHRATEOFFICERSONLYa

Maximum Likelihood Estimates

Log-Likelihood . . . .–67.888 Restricted (slopes = 0) Log-L . . . .–69.303 Chi-Squared (2) . . . .2.8297 Significance Level . . . .0.24296

Standard

Std Mean Deviations

Variable Coefficient Error T-ratio Prob|t|≥x of X of X

ONEb –1.05844 0.185999 –5.691 0.00000 1.00000 0.00000 DESARRc –0.491263 0.307305 –1.599 0.10991 0.33000 0.47139 DESADVd 0.101303 0.273202 –0.371 0.71079 0.32500 0.46955

aRecidivism = presence of an offense or arrest report that indicates a subsequent domestic

incident involving the same suspect and same victim as in the experimental incident

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In an attempt to address concerns regarding the skewed nature of case contributions by officers in the MDVE, distinction has been made between high rate and low rate officers. The 12 high rate officers who met the criterion of turning in ten or more cases tended to follow the experimental protocol much more closely than other officers in terms of properly applying the randomized treatment and not entering ineligible cases into the study. In an effort to improve on the internal validity of the evaluation of treatment effects in the MDVE, cases contributed by the low rate, less conforming officers were excluded from the analyses. When the experimental effects among cases generated by only the high rate officers are examined, they differ from those originally reported for the full sample by Sherman and Berk (1984b) in that the arrest treatment no longer produces statistically significant effects in reducing the prevalence of recidivism as measured by the official police data or the victim interviews. In addition, analyses of treatment effects using a newly constructed incidence measure from the interview data reveals no significant difference across the randomly assigned treatment groups in their effect on recidivism.

NOTES

This research was supported by two grants from the National Institute of Justice: #87-IJ-CX-0049. “A Reanalysis and Critical Evaluation of the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment,” a Graduate Research Fellowship awarded to the author while attending the University of Maryland, and #88-IJ-CX-0007 “The effects of Sanctions on Recidivism: Experimental Evidence,” awarded to the Crime Control Institute. Dr Lawrence W. Sherman served as project director for both grants, as well as faculty advisor for the author’s doctoral dissertation. Opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Institute of Justice, the University of Maryland, or the Crime Control Institute.

1. These officers are referred to as low rate in order to distinguish them from the high-rate officers, although their case generation rates actually range from very low to average.

2. Arrest (n= 66); Advise (n= 65); Separate (n= 69).

3. In the original evaluation of the MDVE, treatment effects were assessed across the delivered treatments, or more accurately, through the use of instrumental variables based on the delivered treatments (Sherman and Berk, 1984b:267). The current method is considered to be more appropriate for the evaluation of randomized experiments such as the MDVE, in that it serves to maximize the benefits of randomization. That is, failure to analyze as you randomize may result in threatening the initial between-groups equivalence which was established through randomization, thus making any conclusions about the effects of treatments on outcomes less certain due to the possible influences of intervening variables. For a more thorough discussion of these issues, see Gartin (1995).

4. This is due to the fact that not all of the victims were interviewed. The original analysis also suffered from this case attrition, with a sample size of 161 cases.

REFERENCES

Berk, R.A. and Sherman, L.W. (1985), “Data Collection Strategies in the Minneapolis Domestic Assault Experiment”, in Burstein, L., Freeman, H.E. and Rossi, P.H. (Eds), Collecting Evaluation Data: Problems and Solutions, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 35-48.

__________ (1988), “Police Responses to Family Violence Incidents: An Analysis of an Experimental Design with Incomplete Randomization”,

Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 83 No. 401, March, pp. 70-76.

Binder, A. and Meeker, J.W. (1988), “Experiments as Reforms”, Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp. 347-358.

Blumstein, A., Cohen, J., Roth, J. and Visher, C.A. (Eds) (1986), Criminal Careers and Career Criminals, Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Cohn, E.G. and Sherman, L.W. (1987), “Police Policy on Domestic Violence, 1986: A National Survey”, Crime Control Reports #5,Washington, DC: Crime Control Institute.

Dunford, F.W., Huizinga, D. and Elliott, D.S. (1990), “The Role of Arrest in Domestic Assault: The Omaha Police Experiment”, Criminology, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 183-206.

Gartin, P.R. (1992), The Individual Effects of Arrest in Domestic Violence Cases: A Reanalysis of the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment, Doctoral dissertation, Institute of Criminal Justice and Criminology, University of Maryland at College Park.

__________ (1995), “Dealing With Design Failures in Randomized Field Experiments: Analytic Issues Regarding the Evaluation of Treatment Effects”,

Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, Vol. 32 No. 4, pp. 425-45.

Lempert, R. (1984), “From the Editor”, Law and Society Review, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 505-13.

__________ (1989), “Humility is a Virtue: On the Publicization of Policy Relevant Research”, Law and Society Review, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 145-161.

Sherman, L.W. and Berk, R.A. (1984a), “The Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment”, Police Foundation Reports, No. 1, Washington, DC: Police Foundation.

__________ (1984b), “The Specific Deterrent Effects of Arrest for Domestic Assault”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 49 No. 2 (April), pp. 261-272.

Sherman, L.W. and Cohn, E.G. (with Hamilton, E.E.) (1986), “Police Policy on Domestic Violence”, Crime Control Reports #1, Washington, DC: Crime Control Institute.

__________ (1989), “The Impact of Research on Legal Policy: The Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment”, Law and Society Review, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 117-144.