Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 19:57

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Survey of recent developments

Stephen V. Marks

To cite this article: Stephen V. Marks (2004) Survey of recent developments, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 40:2, 151-175, DOI: 10.1080/0007491042000205268 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0007491042000205268

Published online: 19 Oct 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 85

View related articles

SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Stephen V. Marks

Pomona College, Claremont CA

SUMMARY

Two major factors, one internal and one external, shaped developments through the middle of 2004. The internal factor was the national election process, which led to a realignment of political power among the parties in the legislative elec-tions in April, and offered the prospect of even greater changes in the presiden-tial election to follow. The external factor was foreign capital, which readily flowed into Indonesia in the early months of 2004, reflected in a series of record highs in the Jakarta Stock Exchange index, but then seemed to waver in May, per-haps because of the growing threat of higher US interest rates, uncertainty about the election, or concern about inflation. Sharp declines in the value of the rupiah and local stocks mirrored similar though less severe developments throughout Southeast Asia and around the globe.

The imminent first-ever election of an Indonesian president through a direct vote by the public raised hopes of change for the better, particularly with respect to governance and the performance of the economy. However, the structural fac-tors that have held back economic growth in Indonesia since the crisis of 1997–98 will not change overnight. The new president could have a popular mandate, but will have to assemble a coalition in a parliament in which power will be more fragmented than ever.

As the presidential election approached, polls showed the electorate’s top pri-orities to be an improved economy and reduced corruption. However, recent months have witnessed several steps backward, as interventions in domestic trade and the escalation of fuel subsidies have created costly inefficiencies and new opportunities for corruption. A recent proposal to establish a vast new social security system monopolised by the government is also problematic in an envi-ronment in which governance remains weak. Personal income tax changes being considered by the Ministry of Finance could significantly reduce government rev-enues, an outcome the government can ill afford.

Despite enactment of a host of new laws in the last six years in such areas as anti-monopoly, bankruptcy and anti-corruption, as well as the initiation of a long-term judicial reform process, recent events have shown that the legal system remains a major source of uncertainty in the business environment.

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/04/020151-25 © 2004 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/0007491042000205268

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

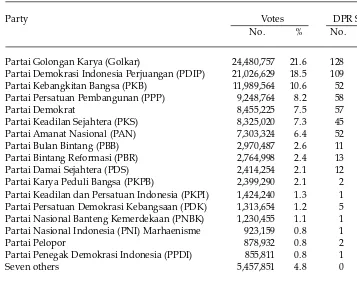

The outcome of the general election of 5 April reflected widespread discontent with the leadership of President Megawati Soekarnoputri and her Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP). The party’s share of the national vote fell from 33.7% in 1999 to just 18.5%. The share of the Golkar party, which finished second overall in 1999, fell by less, from 22.4% to 21.6%, and so it was the overall winner. Five other parties each had at least 6% of the vote, with the remainder split among a host of others. Two new parties drew considerable support: Partai Demokrat (Democrat Party), the vehicle for the presidential candidacy of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, and the Islam-based Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (Prosperous Justice Party). Table 1 shows the votes cast for the various parties in the elections for the national legislature (DPR), and the DPR seats these parties will have.1

The Presidential Election

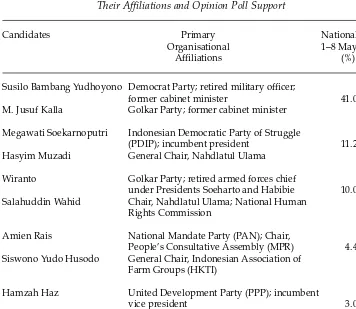

[image:3.559.70.427.93.375.2]The first direct presidential election in Indonesia’s history was to be held on 5 July. As the election approached, five pairs of presidential and vice-presidential contenders emerged, only three with a realistic prospect of victory. Table 2 shows the pairs of candidates—in most cases very odd couples—along with their major institutional affiliations and levels of opinion poll support as of early May. The

TABLE 1 Votes and Seats Obtained by Parties in the DPR Election

Party Votes DPR Seats

No. % No. %

Partai Golongan Karya (Golkar) 24,480,757 21.6 128 23.3

Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan (PDIP) 21,026,629 18.5 109 19.8

Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (PKB) 11,989,564 10.6 52 9.5

Partai Persatuan Pembangunan (PPP) 9,248,764 8.2 58 10.5

Partai Demokrat 8,455,225 7.5 57 10.4

Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (PKS) 8,325,020 7.3 45 8.2

Partai Amanat Nasional (PAN) 7,303,324 6.4 52 9.5

Partai Bulan Bintang (PBB) 2,970,487 2.6 11 2.0

Partai Bintang Reformasi (PBR) 2,764,998 2.4 13 2.4

Partai Damai Sejahtera (PDS) 2,414,254 2.1 12 2.2

Partai Karya Peduli Bangsa (PKPB) 2,399,290 2.1 2 0.4

Partai Keadilan dan Persatuan Indonesia (PKPI) 1,424,240 1.3 1 0.2

Partai Persatuan Demokrasi Kebangsaan (PDK) 1,313,654 1.2 5 0.9

Partai Nasional Banteng Kemerdekaan (PNBK) 1,230,455 1.1 1 0.2

Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI) Marhaenisme 923,159 0.8 1 0.2

Partai Pelopor 878,932 0.8 2 0.4

Partai Penegak Demokrasi Indonesia (PPDI) 855,811 0.8 1 0.2

Seven others 5,457,851 4.8 0 0.0

Totals 113,462,414 100.0 550 100.0

Source: General Election Commission, www.kpu.go.id/suara/dprkursi.php.

polls suggested that in all likelihood there would be a run-off election between the top two pairs of candidates,2unless Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and M. Jusuf

Kalla could muster an outright victory in the initial round despite the weakness of the nascent party apparatus behind the former. If necessary, the run-off would be held on 20 September, with the inauguration of the new leadership to occur in any case on 20 October.

[image:4.559.73.429.87.396.2]As the presidential campaign got under way, there were few discernible differ-ences in the economic policy stances of the candidates. Megawati as incumbent had the clearest track record, which seemed to be her primary disadvantage. However, she also had certain advantages of incumbency. Just before the start of the presidential campaign, for example, it was announced that the government would provide an extra month’s salary to civil servants, the military and the police, and an extra month of pension benefits to retirees (JP, 27/5/04).

TABLE 2 Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates, Their Affiliations and Opinion Poll Support

Candidates Primary National Poll,

Organisational 1–8 May 2004

Affiliations (%)a

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono Democrat Party; retired military officer;

former cabinet minister 41.0

M. Jusuf Kalla Golkar Party; former cabinet minister

Megawati Soekarnoputri Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle

(PDIP); incumbent president 11.2

Hasyim Muzadi General Chair, Nahdlatul Ulama

Wiranto Golkar Party; retired armed forces chief

under Presidents Soeharto and Habibie 10.0 Salahuddin Wahid Chair, Nahdlatul Ulama; National Human

Rights Commission

Amien Rais National Mandate Party (PAN); Chair,

People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) 4.4 Siswono Yudo Husodo General Chair, Indonesian Association of

Farm Groups (HKTI)

Hamzah Haz United Development Party (PPP); incumbent

vice president 3.0

Agum Gumelar Retired military officer; former cabinet minister

aRespondents were asked which of 10 possible candidates would make the best president

for Indonesia; 4.2% indicated a preference for Abdurrahman Wahid, who was disqualified for health reasons from running for president, and 11.3% for other candidates. The remain-der (14.0%) did not know or did not respond.

Source: International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) poll released 31 May 2004, based on face-to-face interviews with 1,000 eligible voters around the country.

MACROECONOMIC PERFORMANCE

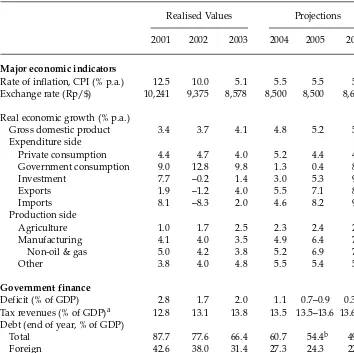

Despite concern about the slow recovery of investment, and real GDP growth well below the rates recorded before the economic crisis, the economy appeared stable in macroeconomic terms through the first months of 2004. Table 3 shows realisations of some main economic indicators for Indonesia over 2001–03, and projections made by the government in early May. The government stuck by its earlier real growth forecast of 4.8% for 2004, and predicted 5.2% real growth in 2005. However, within days of the release of these forecasts, serious signs of

insta-TABLE 3 Recent Macroeconomic Data and Government Projections, May 2004

Realised Values Projections

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

Major economic indicators

Rate of inflation, CPI (% p.a.) 12.5 10.0 5.1 5.5 5.5 5.0

Exchange rate (Rp/$) 10,241 9,375 8,578 8,500 8,500 8,600

Real economic growth (% p.a.)

Gross domestic product 3.4 3.7 4.1 4.8 5.2 5.6

Expenditure side

Private consumption 4.4 4.7 4.0 5.2 4.4 4.0

Government consumption 9.0 12.8 9.8 1.3 0.4 8.0

Investment 7.7 –0.2 1.4 3.0 5.3 9.3

Exports 1.9 –1.2 4.0 5.5 7.1 8.8

Imports 8.1 –8.3 2.0 4.6 8.2 9.7

Production side

Agriculture 1.0 1.7 2.5 2.3 2.4 2.6

Manufacturing 4.1 4.0 3.5 4.9 6.4 7.1

Non-oil & gas 5.0 4.2 3.8 5.2 6.9 7.5

Other 3.8 4.0 4.8 5.5 5.4 5.7

Government finance

Deficit (% of GDP) 2.8 1.7 2.0 1.1 0.7–0.9 0.3–0.5

Tax revenues (% of GDP)a 12.8 13.1 13.8 13.5 13.5–13.6 13.6–13.7

Debt (end of year, % of GDP)

Total 87.7 77.6 66.4 60.7 54.4b 49.3

Foreign 42.6 38.0 31.4 27.3 24.3 22.0

Domestic 45.1 39.6 35.0 33.4 30.4 27.2

aIncludes oil and gas revenues. bData as shown in source.

Source: Rancangan Rencana Kerja Pemerintah (RKP) Tahun 2005[Draft Government Working Plan for 2005], presented at the Parliamentary Budget Committee Working Meeting, 4 May 2004.

[image:5.559.75.429.93.446.2]bility appeared in the form of sharp declines in the value of the rupiah and local stock prices. Both projections may thus turn out to be rather optimistic.

Economic Growth

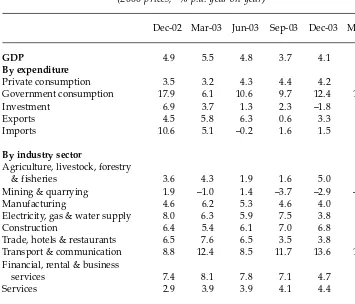

[image:6.559.73.428.94.398.2]Table 4 shows that real economic growth accelerated slightly to 4.5% year on year in the first quarter of 2004. Private consumption continued to grow robustly, though it may slow as the depreciation of the rupiah causes prices of tradable goods to rise. Government consumption had the highest growth rate of any expenditure category, at 12.8% year on year. Investment grew at a moderate rate, though it remains at only about two-thirds of its pre-crisis share of GDP. Exports were nearly flat, while imports surged. On the production side, transport and communication services continued to grow robustly, along with construction and trade, hotels and restaurants. Growth of the manufacturing sector accelerated. Output in the mining sectors, including oil and gas, contracted, while agricultural output was almost flat year on year.

TABLE 4 Components of GDP Growth (2000 prices;a% p.a. year on year)

Dec-02 Mar-03 Jun-03 Sep-03 Dec-03 Mar-04

GDP 4.9 5.5 4.8 3.7 4.1 4.5

By expenditure

Private consumption 3.5 3.2 4.3 4.4 4.2 5.7

Government consumption 17.9 6.1 10.6 9.7 12.4 12.8

Investment 6.9 3.7 1.3 2.3 –1.8 4.2

Exports 4.5 5.8 6.3 0.6 3.3 0.8

Imports 10.6 5.1 –0.2 1.6 1.5 6.5

By industry sector

Agriculture, livestock, forestry

& fisheries 3.6 4.3 1.9 1.6 5.0 1.5

Mining & quarrying 1.9 –1.0 1.4 –3.7 –2.9 –2.7

Manufacturing 4.6 6.2 5.3 4.6 4.0 5.5

Electricity, gas & water supply 8.0 6.3 5.9 7.5 3.8 2.2

Construction 6.4 5.4 6.1 7.0 6.8 7.3

Trade, hotels & restaurants 6.5 7.6 6.5 3.5 3.8 6.1

Transport & communication 8.8 12.4 8.5 11.7 13.6 13.8

Financial, rental & business

services 7.4 8.1 7.8 7.1 4.7 4.9

Services 2.9 3.9 3.9 4.1 4.4 4.4

Non-oil & gas GDP 5.9 7.0 5.6 4.2 4.8 5.0

aExpenditure data calculated by splicing 2000 price data onto 1993 price data.

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

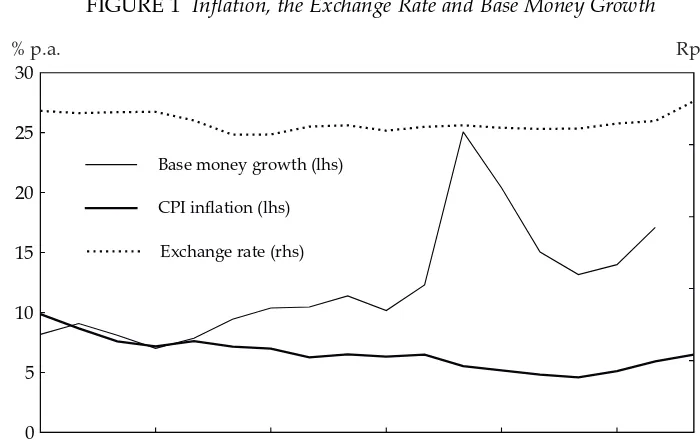

Inflation and the Exchange Rate

Consumer price index (CPI) inflation reached a low of 4.6% year on year in February 2004, but then rebounded in March, April and May (figure 1). The increase in inflation was initially only minimally related to the exchange rate: the rupiah depreciated against the dollar by 1.7% in March, and by only 0.9% in April. However, in May it depreciated by 6.3%, and year-on-year inflation accel-erated to 6.5%. For the purpose of comparison, table 5 shows changes in the value of various currencies in terms of the dollar over the first five months of 2004. Indonesia experienced by far the greatest depreciation among all the Asian coun-tries listed, with only Brazil coming close to it among the other councoun-tries.

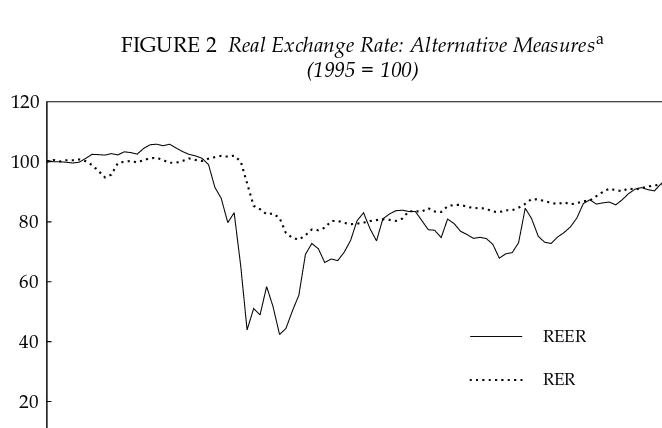

To put this depreciation in context, particularly given recent shifts in the rela-tive values of currencies of other nations, figure 2 shows two alternarela-tive meas-ures of the real exchange rate. One of these is the real effective exchange rate (REER), which compares wholesale prices in Indonesia with those in other coun-tries, expressed in common currency units, and thus provides an indication of the competitiveness of tradable goods produced in Indonesia.3The massive nominal

[image:7.559.79.429.77.297.2]depreciation of the rupiah in 1997–98 made Indonesia’s tradable goods highly competitive, but since then the nominal appreciation of the rupiah has exceeded the difference between inflation in Indonesia and in other countries. By the end of 2003, despite the negative long-term consequences of the 1997–98 crisis for the country, this index was within 4.5% of its value in 1995. The alternative measure of the real value of the rupiah shown in figure 2 is the real exchange rate (RER). It is the ratio of non-tradable to tradable goods prices within Indonesia, and thus shows the prices faced by domestic producers and consumers. On this basis, the real depreciation of the rupiah during the crisis was much less severe, and the

FIGURE 1 Inflation, the Exchange Rate and Base Money Growth

Dec-20020 Mar-2003 Jun-2003 Sep-2003 Dec-2003 Mar-2004

5 10 15 20 25 30

0 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000

% p.a. Rp/$

CPI inflation (lhs)

Base money growth (lhs) Exchange rate (rhs)Source: CEIC Asia Database.

FIGURE 2 Real Exchange Rate: Alternative Measuresa (1995 = 100)

Jun-19950 Jun-1997 Jun-1999 Jun-2001 Jun-2003

20 40 60 80 100 120

REER

RERaSee text for an explanation of both measures.

[image:8.559.83.414.392.606.2]Sources: REER: International Monetary Fund (IMF), International Financial Statistics, calcu-lations by the author; RER: Bank Indonesia (unpublished).

TABLE 5 Change in Value of Various Currencies against the Dollar, Jan–May 2004 (%)

Asia Non-Asia

Korea +2.7

United Kingdom +2.6

Russia +0.9

India +0.1

Singapore +0.0

Malaysia +0.0

Hong Kong –0.4

Philippines –0.4

Pakistan –0.8

Argentina –1.1

Mexico –1.5

Japan –2.2

Thailand –2.3

Euro Area –3.2

New Zealand –3.7

Australia –5.1

Canada –5.2

Brazil –8.6

Indonesia –8.9

Source: Pacific Exchange Rate Service, University of British Columbia, fx.sauder.ubc.ca.

currency has subsequently recovered nearly all its lost ground, so that the incen-tives given by these prices are not much different from those prior to the crisis.

Minimum wage growth has moderated, after several years of dramatic increases in many parts of the country (Alisjahbana and Manning 2002). For example, the increase in Jakarta was just 6.8% for 2003 and 6.3% for 2004—in both cases close to or below the rate of inflation. However, a measure now under dis-cussion would change the basis for calculation of minimum wages. The present standard is a market basket of 43 commodities said to constitute ‘minimum life needs’ (kebutuhan hidup minimum). The new standard would be an expanded mar-ket basmar-ket that would constitute ‘suitable life needs’ (kebutuhan hidup layak). There is some concern that this more ambitious basis could cause minimum wages to jump in the future, putting further pressure on employment in the modern sector (box 1). In any case, for the present, moderate depreciation of the rupiah may be

BOX 1 40 MILLIONUNEMPLOYED?

It has become the ‘conventional wisdom’ that Indonesia faces a major problem of labour absorption, with some 40 million people registered as unemployed. This figure is cited frequently by presidential candidates and social commentators alike, yet it has no scientific basis, and bears little relationship to labour market realities. Worse, focusing on unemployment as Indonesia’s major labour issue distorts the relevant policy choices.

Unemployment is defined precisely in international and Indonesian national surveys as the number of people both not working and seeking work during a specified reference period. According to the latest (2003) National Labour Force Survey data, the unemployment rate amounts to 9.5% of the total labour force, or some 9.5 million persons out of a work-force of 100 million—a far cry from the often quoted 40 million.

As found in previous annual surveys, the urban, young and educated comprise a much higher proportion of the unemployed than might have been expected on the basis of their shares in the total workforce. Many studies have shown that a significant proportion of these individuals are unemployed by choice—in the sense that they are, in effect, queuing for better modern sector jobs after completion of school and university rather than taking on readily available but less attractive jobs. In short, not only is the true level of unemployment less than one-quarter of the popularly quoted figure, but also a large part of the true total represents voluntary unemployment. Programs often suggested for dealing with the unemploy-ment problem, such as job creation activities in villages or assistance to small-scale enterprises, are unlikely to affect the behaviour of urban youth looking for better jobs in the cities. It is precisely jobs of this kind that they are seeking to avoid.

The figure of 40 million is in fact an approximation to the sum of the 9.5 million actually unemployed and about 28 million people reported as

beneficial from the viewpoint of expanding job opportunities (by virtue of reduc-ing wage costs expressed in foreign currencies), given the substantial real wage increases of recent years and given that productivity growth has been slow in Indonesia compared with competitor countries, China in particular.

Capital Flows and Stock Prices

With the expiry of the concessional agreement between Indonesia and the Paris Club of creditor countries in December 2003, the government is now obliged to rely more on commercial creditors. On 3 March, a government issue of $1 billion worth of 10-year dollar-denominated debt with an effective yield of 6.85% p.a. (a spread of 277 basis points over yields on 10-year US Treasury bonds) was warmly received by foreign creditors. On the other hand, the Ministry of Finance reports that foreign investors sold off 22.5%, or about Rp 1.9 trillion (roughly $200

mil-working less than 35 hours a week (this total was actually 38 million in 2003). The latter group is often referred to as the ‘under-employed’, but this is also misleading because the category includes a high proportion of people, many of them married females and children, who work less than 35 hours a week by choice (estimated at 16 million in the 2003 survey). They are not under-employed in the conventional sense of working less than the arbitrary stan-dard of 35 hours and seeking more work, but are voluntarily under-employed in the sense of choosing to work ‘part time’—that is, less than this standard.

Neither the unemployment nor the under-employment figure captures the essence of the main labour market problem—low productivity resulting in low wages—which affects a much higher proportion of the workforce. The big policy issue is not creation of jobs per se: the informal sector offers a ready outlet for work if individuals and families are desperate and, indeed, those most in need cannot afford to be out of work. Rather, it can be argued that the key problem is creation of ‘better’ jobs through policies that induce more investment and greater efficiency in the use of labour and other factors of production, thus raising productivity and wages, with flow-on effects for improved living standards and reduced poverty. To portray the key issue as finding jobs for a fictitious ‘40 million unemployed’ is to divert attention from this much more important agenda. Recent attempts to regulate the labour market for the benefit of workers, including implementation of an aggressive minimum wages policy that is likely to deprive many workers of the opportunity to graduate from informal sector activities into more pro-ductive formal sector employment (Manning 2004), would not seem to have helped in this regard.

Chris Manning ANU BOX 1 (continued) 40 MILLIONUNEMPLOYED?

lion), of their holdings of rupiah-denominated government debt at the end of March, thus providing a clear indication of concern about the risk of renewed rupiah depreciation. Indeed, the rupiah lost 11.2% of its value against the dollar between 27 April and 2 June.

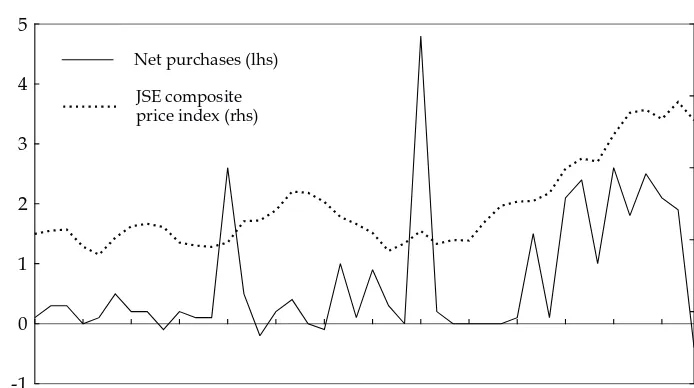

The rupiah value of the Jakarta Stock Exchange (JSE) composite index hit record highs during January, February and April 2004, though its foreign cur-rency value remained well below the peak levels attained before the 1997–98 cri-sis. However, after reaching a record high of 818 on 27 April, the index retreated sharply over the next several weeks. By the end of May it was down 10.5% from its record level the previous month, compared with a decline of 9.8% in stock prices in emerging markets overall during the same period.

In the midst of this turbulence, Bank Indonesia (BI) governor Burhanuddin Abdullah wrote to four unnamed foreign banks warning them to refrain from speculating against the rupiah (JP, 14/5/04). While central bankers sometimes use moral suasion against speculators at such times, some observers argued that the warning would be counterproductive because it implied that BI saw itself as powerless to influence the strength of the currency through its own policies.

Speculation is usually viewed negatively in Indonesia, and in many other countries. However, it is useful to revisit the ancient truth that profitable specu-lation stabilises prices, since it is the profitable speculator who buys when prices are low and sells when they are high. Thus, speculators who do profit help to sta-bilise the market, while speculators who do not help to stasta-bilise the market are punished by the market itself. This may be cold comfort to policy makers, since herd behaviour can emerge in which the individually but not collectively rational decisions of market participants can greatly increase the volatility of asset prices. In that case it is important for the central bank to adjust fundamen-tal monetary conditions sensibly to help calm these markets. A contraction of liq-uidity and a consequential increase in interest rates could help stem capital flight, for example.

The net value of foreign purchases of shares at the JSE has been positive dur-ing every calendar year since 1995, though without question foreign activity has at times exacerbated market volatility. Figure 3 shows the JSE index on a monthly basis since 2000, as well as net purchases by foreigners. For almost all months during this period, net buying by foreigners has been positive. Foreign investors missed the start of the rally in the JSE in early 2003, but were soon on board and appear to have contributed significantly to it. However, the net foreign purchase value for May 2004 showed a sharp swing to net sales by foreigners, which coin-cided with the sudden weakening of the rupiah. Clearly it was not just a handful of banks that were concerned about the currency, and it will take more than moral suasion by BI to stabilise it. Of paramount importance is whether the central bank’s commitment to sound monetary policy is credible.

Global Financial Instability to Return?

Observers as diverse as Kenneth Rogoff, former chief economist of the IMF, and Joseph Stiglitz, one of the IMF’s most prominent critics in recent years, have worried that a financial bubble may have emerged in developing countries, pro-pelled by loose monetary policy in the US (Wall Street Journal, 23/1/04). Rogoff suggests that an international financial crisis could recur within two to three

years (Financial Times, 1/4/04). Such a crisis would presumably be triggered by the inevitable tightening of credit in the US as its economy rebounds in a con-text of persistent fiscal deficits, given the relatively high levels of public debt to GDP in emerging market economies. With total public debt at 66.6% of GDP at the end of 2003, Indonesia was close to the global average, which the IMF puts at about 70%.

One indicator of a possible bubble has been the narrowing of spreads between interest rates on public debt in emerging markets and those on US Treasury secu-rities. The concern is that these spreads will increase significantly as credit tight-ens in global capital markets. An increase in interest rate spreads is already evi-dent for Indonesia: for the March issue of international bonds mentioned earlier, the spread rose from the initial 277 basis points to more than 400 basis points by early May. The prospect of higher interest rates on domestic debt has become more immediate as well: an auction of Rp 3.5 trillion ($379 million) of govern-ment debt was cancelled in late May because potential buyers demanded higher yields than the Ministry of Finance wished to pay (Bisnis Indonesia, 26/5/04).

[image:12.559.79.426.102.296.2]It is difficult to say how well prepared Indonesia is to weather a new financial crisis, particularly when so much depends on intangible factors like the quality of political leadership, but one simple macroeconomic indicator appears to offer comfort. Figure 4 shows that foreign exchange reserves net of IMF credits have trended upward since early 1998, and particularly since the middle of 2002. From late April through late May, however, BI sold nearly a billion dollars worth of for-eign exchange (mostly not shown in figure 4) to support the rupiah. To put these reserve levels in some context, BI reported that public offshore debt stood at $82 billion and private offshore debt at $52 billion in March. Total foreign debt

FIGURE 3 Net Purchases by Foreigners, and the Jakarta Stock Exchange Index (Rp trillion)

Dec-2000-1 Dec-2001 Dec-2002 Dec-2003

0 1 2 3 4 5 0 200 400 600 800 1,000

Net purchases (lhs)

JSE compositeprice index (rhs)Sources: Datastream; Jakarta Stock Exchange; Bapepam.

service rose 39% in March to $1.96 billion during that month (JP, 8/6/04). Other factors relevant to the resilience of the economy will be discussed later, in the context of fiscal policy and bank regulation.

MONEY AND BANKING

The accelerating rate of monetary expansion noted by Kenward (2004) may have set up the rupiah for its recent weakness (figure 1). Over the long run, a rate of money growth equal to the sum of inflation and real economic growth is to be expected; on this basis, the growth rate of money consistent with the govern-ment’s growth and inflation projections (table 3) is around 10% p.a. Toward the end of 2003, monetary expansion was excessive by this standard. The growth rate of base money peaked at 25.2% year on year in November 2003, though it had eased to 17.1% by April 2004 (figure 1).4One of the reasons for the expansion of base money towards the end of 2003 was the mutual fund crisis described by Kenward (2004), in response to which BI injected extra liquidity into the economy. Nevertheless, base money growth has clearly trended upward since the second half of 2002, despite moderate real growth and, until the last few months, declin-ing inflation.

Interest Rates

[image:13.559.84.414.98.294.2]The evidence of excessive monetary expansion in recent months is mirrored by evidence on interest rates. Figure 5 compares the nominal rate of interest on three-month BI Certificates (SBIs) with that on three-month US Treasury bills.

FIGURE 4 International Reserves and Use of IMF Credita

($ billion)

Dec-19950 Dec-1997 Dec-1999 Dec-2001 Dec-2003

5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Reserves

IMF credit Reserves net of IMF creditaReserves include both foreign exchange and Special Drawing Rights (SDRs).

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics.

With investors able to move their funds internationally, interest rates in Indonesia will have to exceed foreign interest rates by enough to compensate investors for perceived risks plus the expected rate of depreciation of the rupiah. The dramatic narrowing of the spread between US Treasury bills and SBIs to roughly 6% in recent months would have made financial investment in Indonesia less attractive, leading eventually to a sell-off of rupiah assets. The actualrupiah depreciation that has occurred may have reduced the expectedfuture depreciation of the cur-rency, thus inducing investors to hold rupiah assets once more, although this view must be qualified with reference to investor expectations about the future conduct of monetary policy.

Under the 1999 law on BI, the mission of the central bank is to maintain a sta-ble value of the rupiah. Why, then, has BI been so obsessed with lower interest rates? One reason is that it wishes to avoid issuing more SBIs through open mar-ket operations as a means of removing excess liquidity, since this would increase its own interest expenses. Another is that higher interest rates would increase the interest burden on the government. The policy independence of the central bank in the midst of the presidential election is also rather suspect, since lower interest rates tend to benefit incumbent politicians.

[image:14.559.87.416.100.297.2]A final motivation is to coax additional lending to the corporate sector from the banking system. Although investment lending from banks increased 16% year on year in April, this was from a low base as a result of large-scale loan write-offs fol-lowing the banking collapse of 1998–99, making this number difficult to interpret. In real terms the April amount outstanding was only 45% of that in April 1997. However, the real sector has benefited considerably since the crisis from being

FIGURE 5 Indicator Interest Rates: Three-Month SBIs and US Treasury Bills (% p.a.)

Dec-20000 Dec-2001 Dec-2002 Dec-2003

4 8 12 16 20

Treasury bills SBIs

Sources: Bank Indonesia; US Council of Economic Advisors, Economic Indicators, www. gpoaccess.gov/indicators/index.html.

able to repurchase much of its original bank borrowings at a fraction of their orig-inal value (either from the banks themselves or from the government via the banks and non-performing loans that the government took over). Moreover, it is debatable whether the low real level of lending is a cause or an effect of the slug-gish recovery of investment. In any case, many companies have turned to the bond market as an alternative to bank loans. The value of corporate bonds out-standing more than doubled between 2001 and 2003, and at the end of 2003 equalled 67.3% of investment loans from banks.

By the end of May, BI publicly recognised that excess liquidity in the financial system had to some extent fuelled the speculation against the rupiah. Senior deputy governor Anwar Nasution blamed the excess of liquidity on the slow recovery of bank lending to the corporate sector (JP, 29/5/04), though clearly BI had itself generated this excess liquidity through expansion of base money in its pursuit of lower interest rates.

In early June, as the rupiah depreciated to Rp 9,590/$, BI announced that measures would be taken to absorb some liquidity, and that SBI interest rates would not be allowed to go lower. The principal measure was to be an increase in the minimum reserve ratio (that is, the ratio of each bank’s deposits at BI to its customers’ deposits), from 5% to 6, 7 or 8%, depending on the size of the bank’s total deposits. This policy, to be implemented in July, would increase the demand for base money relative to supply, and thus have the same impact as the sale of SBIs. For BI, however, it had the advantage of being cheaper, as the central bank intended to pay a much lower interest rate (3% p.a.) on compulsorily increased reserves than it would have to pay on voluntarily purchased SBIs. For market interest rates, however, the impact would be much the same, since there would be a corresponding decrease in the supply of base money relative to the demand for it.

The Banking System

Regulatory and institutional weaknesses in the banking system persist. On the heels of the scandals at the state-owned Bank Negara Indonesia and Bank Rakyat Indonesia in late 2003 (Kenward 2004), BI closed two small banks, PT Bank Dagang Bali and PT Bank Asiatic, on 8 April. These closures did not pose a threat to the stability of the banking sector, given the small size of the banks (JP, 13/4/04). Nevertheless, with its blanket guarantee of bank liabilities, the govern-ment could be liable for up to Rp 3.4 trillion in combined liabilities of the two banks, with Rp 2.2 trillion in combined deposits. The episode was a reminder that future potential liabilities for the central government lurk beneath the surface of the banking system.5

The practices that led to the closure of the two banks can best be described as fraud. The banks were both captive to family business groups. Each appears to have been plundered by its owners (who were related to each other by marriage) through the extension of loans to related entities that were covered up by falsi-fied accounts. BI has been criticised for its handling of this episode, since it had known about serious problems at the banks since mid 2001 (Kompas, 25/4/04). For their part, BI officials argue that initially it was hoped that the situation could be turned around through close supervision and technical assistance. The suspect legal system once more played a central role: no owners of troubled

banks, even those who engaged in fraud, have been sent to prison following the banking collapse of 1998–99; a few have been convicted, but have fled the coun-try to avoid prison terms. When the consequences of illegal behaviour are few and the potential gains great, it should come as no surprise that such behaviour persists.

Finally, there is continuing concern both inside and outside BI about the poor management of the state banks. The fundamental problem is the absence of a residual claimant—an owner with a controlling interest in the banks—who will have a strong incentive to enforce strict internal controls and clean up lending practices. As one government official put it to me, nobody gets fired in state banks. The sale of minority stakes will not solve the problem.

FISCAL ISSUES

The fiscal situation has improved, as reflected in simple measures such as the debt to GDP ratio and in more sophisticated measures of fiscal sustainability (Marks 2004, in this issue). However, concern about the government’s potential burdens under the blanket guarantee of bank liabilities, or even under more lim-ited deposit insurance, has been heightened by the closures of Bank Dagang Bali and Bank Asiatic. In addition, new concerns about increased expenditure and possibly reduced tax revenues have emerged, in each case partly related to the presidential election.

Increased Burden of Fuel Subsidies

The public sector as a whole gains on net (through tax and non-tax revenues) from higher oil prices, but the central government itself loses from the fuel sub-sidy as well as from the sharing of natural resource revenues with the regions.6

The subsidy was originally budgeted at Rp 11.4 trillion in 2003 (0.6% of GDP), but eventually cost Rp 26.0 trillion (1.5% of GDP), primarily as a result of higher petroleum prices. The cost of the subsidy for 2004 was originally put at Rp 14.5 trillion, based on a crude oil price of $22 per barrel and an exchange rate of Rp 8,300. But by May, with average crude oil prices at $35 or higher and the rupiah weaker, the national oil and gas company Pertamina estimated that the cost of the subsidy could rise to Rp 40 trillion in 2004 (JP, 27/5/04)—more than 10% of the state budget and at least 2.0% of the revised GDP estimate.

The high cost of the subsidy was exacerbated by the election-year decision to hold fuel prices constant throughout 2004. Previously, fuel prices had been linked to a Singapore benchmark gasoline price. To get a sense of the magnitude of the subsidy per unit, at the start of 2004 the spot wholesalegasoline price in Singapore was 26.6% higher than the retail gasoline price in Indonesia. Gasoline prices in Singapore then rose by 14.4% in dollar terms, and by 22.4% in rupiah terms, by mid May.7,8The costs of the subsidy increase with higher oil prices and a weaker

rupiah not only because of a higher subsidy per unit of fuel consumed, but also because measured consumption tends to rise owing to increased illegal diversion of fuel products to other countries.

In March and April, Indonesia became a net importer of crude oil for the first time (Asian Wall Street Journal, 18/5/04). With crude oil prices at 13-year highs, this development was especially painful. It was related not only to the fuel

sidies, which kept demand high, but also to moribund production due to low investment in oil exploration and oilfield development.9

Further, the differential between the official price of kerosene for households (Rp 700 per litre) and industry (Rp 1,800) causes shortages for households, since kerosene intended for domestic use gets diverted illegally to industry. In early May, the Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources vowed that Pertamina would revoke the licence of any retailer caught engaged in such diversions (JP, 6/5/04). Discussions earlier in the year about adding colour to kerosene intended for households broke down over the question of who would bear the cost. The best approach would be simply to sell kerosene at a single price to all buyers, since households are paying almost as much as industrial users anyway, and have faced shortages (JP, 19/4/04). In the process, corruption would be reduced.

Tax Policy

Fiscal policy makers emphasise the importance of expanding tax revenue. In practical terms, this would provide some protection against additional govern-ment liabilities from bank failures, compensate for diminished net natural resource revenues and the burdens of fiscal decentralisation and bureaucratic reform, and allow for additional economic development expenditure. Yet the government’s own projections indicate that tax revenues will remain flat as a per-centage of GDP over the next several years (table 3). It is thus of concern that changes in personal income taxation that would significantly reduce revenues have been under consideration within the government. In May the Ministry of Finance projected revenues from these personal income taxes to be Rp 47.9 tril-lion in 2004, which would be 13.5% of total central government revenues or 2.4% of GDP.10

Under the new proposal, personal tax exemptions (penghasilan tidak kena pajak, or PTKP) would be increased this year, and the top marginal income tax rate would be lowered from 35% to 30% within five years.11The current and proposed

exemptions are shown in table 6. The Ministry of Finance (2004) has estimated that enlargement of the exemptions would lower revenues by Rp 5.6 trillion, or about 0.3% of projected 2004 GDP, but did not estimate the revenue impact of the cut in the top rate.

TABLE 6 Proposed Changes in Personal Income Tax Exemptions, 2004

Current Income Tax Law Proposed Level

Personal income tax exemptions (Rp)

Taxpayer 2,880,000 12,000,000

Working spouse 2,880,000 12,000,000

Non-working spouse 1,440,000 1,200,000

Other dependants 1,440,000 1,200,000

Maximum number of other dependants 3 2

An argument could be made for reduction of the top rate on the grounds that it would lessen incentives for tax avoidance and evasion, and would provide incentives for additional work effort and saving. There may also be merit in adjustment of the tax system in a way that would excuse more lower-income households from paying taxes, on the grounds of both equity and administrative efficiency. In fact, a 2003 decree of the Minister of Finance does just that: the gov-ernment now bears the income taxes on the first Rp 1 million of monthly labour income for workers whose monthly wage is Rp 2 million or less.12The ministry

estimated the budgetary cost of this measure at Rp 2.2 trillion in 2003.

The problem with the large proposed increase in exemptions is that not only are many lower-income taxpayers relieved of personal income tax obligations, but also the taxes of all higher-income earners are cut, since the entire tax sched-ule is lowered. My own rough estimate of the net budgetary cost of the increased exemptions is Rp 16.0 trillion or 0.8% of GDP. This estimate comes from a detailed analysis of the personal income tax system based on data from the 2002 National Socio-Economic Survey (Susenas). The methodology for an earlier version of this analysis is described in detail in Marks (2003). The basic approach is to calculate income tax payments, household by household, based on application of the income tax code, and then use Susenas household weights to estimate tax pay-ments on a national level.

One concern with this approach is that there is no way to identify the income on which taxes are actually paid. I assume that it is not feasible to tax farm income, but that other business and rental income is taxed. I also assume that only the wages of regular workers are taxed (the self-employed and those with-out a fixed employment relationship are excluded), and I exclude occupations for which income is hard to tax (such as street vendors, household servants, public transportation drivers, and workers in agriculture, forestry and fisheries). Given these and other assumptions necessitated by data limitations and imperfections, the estimated levelof income tax revenues predicted from this analysis is not very reliable; I estimate it at Rp 25.1 trillion based on application of the current income tax law and at Rp 16.0 trillion if the proposed measures are implemented.13

However, the difference in the level of personal income tax revenues generated by these two policies is more reliable, since the errors that affect both of these levels similarly tend to cancel out; I estimate the revenue loss caused by the new policy at 39.9% of personal income tax revenues. Application of this figure to the Rp 47.9 trillion in personal income tax revenues projected for 2004 yields my net cost esti-mate of Rp 16.0 trillion.14

It is not clear whether this estimate is more or less accurate than the figure of Rp 5.6 trillion derived by the Ministry of Finance. The conclusion I draw from this analysis is simply that there is some risk that the policy change could be very costly, and that further examination of the proposal is merited. Also, in fairness to the ministry, the increase in personal income tax exemptions was part of a larger package. It proposes to compensate for the lost personal income tax rev-enues through changes in the value added tax system, taxation of bond mutual fund interest, application of higher penalty income tax rates to individuals with-out tax identification numbers, and use of deemed income for business owners with turnover of less than Rp 1.8 billion. The last of these measures could be con-troversial, however, and certainly could hurt small business.

Proposed Social Security System

The government submitted legislation to the DPR in December 2003 that would establish a comprehensive social insurance system for Indonesia. Although the details of the plan have not been made public, a basic outline has emerged. The system would be administered by the central government, and participation would be compulsory. It would consist of a pension system, national health insur-ance, worker disability and death benefits, and an old-age saving scheme.

The pension system would consolidate the existing pension programs for the military, civil servants and private sector employees, but would also extend cov-erage to those currently without a pension. It would use a defined benefit approach—promising a pre-specified level of pension benefits—which recent reports have put at 70% of the minimum wage. Since there are now well over 100 different minimum wages throughout Indonesia, this would not only tend to be unworkable but would also mean that the basis for the increase in pension dis-bursements would be a highly uncertain policy variable that regional govern-ments could manipulate at the expense of the central government.

The old-age saving plan would use a defined contribution approach, in which a lump sum payment would be made upon the retirement, death or dis-ability of the worker, equal to the contributions made on the worker’s behalf plus investment income. Contributions for health insurance, the pension and old-age savings would be split equally between employers and employees, while the death and disability benefits would be funded by employers only. Current discussions put the sum of employer and employee contributions at 6% of the gross wage for national health insurance and perhaps as much as 13% for the other components. These rates would be well above contribution rates in comparable developing countries. More importantly, they appear to have been determined quite arbitrarily, rather than on the basis of the extensive and detailed actuarial calculations that usually underpin properly designed social insurance plans.

The contributions burden for the pension system would fall principally on workers in the modern sector—less than 30% of the total workforce—and their employers. Proponents of the legislation claim that contributions would also be obtained from some informal sector workers, but Bird (2003) notes that experi-ence in countries at comparable levels of development shows that it is virtually impossible to collect medical or pension premiums from such workers. Collections can be difficult even in the formal sector. Currently only nine million of an estimated 25 million regular wage workers in the private sector contribute to the supposedly compulsory Jamsostek (Jaminan Sosial Tenaga Kerja, Worker Social Security) pension program.15The avoidance problem might not be so bad

if workers had confidence in the program, but Arifianto (2004) notes that both rates of return on Jamsostek investments and benefit payments have been low. A system in which workers in the modern sector effectively cross-subsidised infor-mal sector workers would be even less attractive. Either the payroll tax would be evaded or it would reduce employment in the modern sector.

The draft law specifies that the government will pay some portion of the costs of coverage of individuals under the health insurance program. The problem here is that health care costs typically escalate dramatically because of increased demand under programs that reduce health care costs to the user, unless benefits

are restricted to a fraction of the population (such as workers in the formal sec-tor) and strict caps on benefits are imposed. Experience in comparable countries shows that enforcement of benefit caps is difficult because of weaknesses in administrative capacity, so the program would almost inevitably lead to substan-tial unfunded liabilities for the government.

To the extent that the public is aware of it, the legislation has met with resist-ance (JP, 18/5/04). Stakeholders have expressed concerns over governance capacity and financial leakages, given the poor record of state monopolies— including Jamsostek—in the management of public funds to this point. Indeed, Arifianto (2003) notes that countries like Argentina, Chile and Mexico no longer rely on state monopolies to provide social insurance, but instead have introduced competition among providers in order to enhance performance and accountabil-ity. The Ministry of Finance has not begun to analyse the potential fiscal implica-tions of the scheme.

TRADE POLICY

The protectionist thrust in trade policy in agricultural sectors in recent years has remained in evidence, with a number of new interventions in relation to domes-tic trade in pardomes-ticular.

Sugar

The Minister of Industry and Trade, Rini Soewandi, decreed in 2002 that only a limited number of state enterprises would be allowed to import sugar, presum-ably in the expectation that they would restrict total imports.16These enterprises

currently consist of two state trading companies and three state plantation com-panies that operate sugar mills. More recently, the Business Competition Supervisory Commission (Komisi Pengawas Persaingan Usaha), under its man-date to point out government policies that can lead to monopolistic practices or unfair competition, observed that the sugar import restraint system could give rise to cartel practices, and suggested that it be revised (Tempo Interaktif, 29/3/04). Nevertheless, the value of sugar imports increased by 54.2% between 2002 and 2003, even though the decree was issued in late September 2002. The cartel seems to have worked most imperfectly!

The failure to curtail sugar imports may have motivated two new decrees (the second a revision of the first) from the ministry in 2004, prohibiting inter-island trade in imported white sugar.17Inter-island trade is now limited to certain types

of locally produced white sugar, and to registered traders, who have to get per-mission from the ministry for each shipment. These restrictions mean, in princi-ple, that each importer would have a stronger incentive to restrict imports, since it would not be able to sell sugar without permission in the marketing areas of other importers. The cartel should work more effectively.

The new policy was put into action in March, when 179 containers filled with 3,674 tons of imported sugar were confiscated by government officials at Tanjung Priok port in Jakarta after it was determined that the sugar had been illegally shipped from North Sumatra by the state trading company PT Perusahaan Perdagangan Indonesia (JP, 23/4/04). The contents of 162 of the containers were subsequently destroyed.

Rice

Given the abundance of rainfall in recent months, rice harvests on Java are pro-jected to exceed targets this year. In May, the Minister of Industry and Trade recom-mended that the rice import ban put into effect in January and set to expire on 30 June be extended, for a length of time to be determined upon further review (Koran Tempo, 22/5/04). Some observers emphasise the need for a mechanism to be read-ied for the resumption of rice imports after the end of harvest seasons. The matter is complicated by differences in the interests of the Ministry of Agriculture (which stakes its legitimacy with farmers on higher rice prices) and the Ministry of Industry and Trade (which might want to be able to license more trading activity, perhaps in order to generate rents). In the recent past, rice import shipments have required the approval of the Ministry of Industry and Trade on a case-by-case basis.

Fertiliser

A 2003 decree of the Minister of Industry and Trade re-regulated the distribution of fertiliser down to the retail level. The decree specified separate geographic dis-tribution areas for the five producers of urea fertiliser, for which natural gas input is subsidised.18It also specified that the Minister of Agriculture was to set

maxi-mum retail prices for all fertilisers whose production was subsidised, and that these fertilisers could only be imported by the companies that produced them. Within two months a revised decree was issued, allowing registered importers also to import fertilisers.19If this convoluted set of arrangements was intended to

assist farmers, tight restrictions on imports would not contribute to this aim! In February 2004 the Minister of Agriculture established maximum retail prices for four varieties of fertiliser.20For urea, the price was set at Rp 1,050 per

kilogram. Recent data from the three main agricultural provinces of Java indicate the price at the farm level to be around Rp 1,400–1,500/kg, however. There have been reports of shortages in various parts of Java (JP, 23/4/04; Media Indonesia, 22/5/04). One important stakeholder, the chairman of an association of farmers and fishermen in East Java, stated that the scarcity of urea had resulted from the distribution system instituted by the Ministry of Industry and Trade. Prior to that, there had been no problems (Kompas, 24/5/04).

This observation seems very plausible. The maximum retail prices apply only to small farmers, while large plantations are supposed to pay a market price. Thus, in parallel with the kerosene market, fertiliser distributors at all levels have incentives to divert fertiliser to the export market or to plantations. Recently the Ministry of Industry and Trade complained that the 2003 fertiliser decree was not being obeyed, and introduced criminal and severe administrative sanctions for producers, distributors or retailers that violated its distribution scheme.21These

measures are in contradiction of normal economic incentives, and are bound to lead to greater economic and bureaucratic inefficiencies.

LEGAL DEVELOPMENTS

One of the less predictable aspects of the economic environment in Indonesia in recent years has been the legal system. In October 2003, under the direction of the Chief Justice, the Supreme Court completed a comprehensive set of blueprints for long-term court reform. The product of 18 months of study, these documents

acknowledge that serious problems exist, and identify the major areas that need to be reformed. The Chief Justice suggests that this process could take up to 15 years, but can the country afford to wait as long as that? If contracts and property rights are not predictably upheld, higher rates of investment and growth will remain elusive. Forceful and concerted leadership is vital.

Official awareness of the need for reform has not prevented controversial ver-dicts from being rendered. In February the Supreme Court reversed the convic-tion on corrupconvic-tion charges of Akbar Tandjung, Chair of the DPR and General Chair of the Golkar Party. The guilty verdict had been delivered by the Central Jakarta District Court, and upheld in an appellate court. Later in the year came two cases of special concern to foreign investors.

The Prudential Assurance Case

A new symbol for the risky foreign investment climate in Indonesia emerged in April in the form of PT Prudential Life Assurance, the 94.5% foreign-owned sub-sidiary of the UK-based Prudential Assurance Company. The Indonesian com-pany was declared bankrupt on 23 April in the Commercial Court in Central Jakarta, in response to a petition filed by one of its former agents, who claimed to be owed some Rp 366 billion ($44 million) in bonuses. The company was also ordered to pay the former agent $400,000 (JP, 1/5/04).

Now in its eighth year of operation in Indonesia, Prudential had earned pre-tax profits of Rp 71 billion in 2003, its third consecutive profitable year. It had Rp 1.56 trillion ($183 million) in assets at the end of that year as a result of strong growth in its premium income (JP, 29/4/04). Its risk-based capital ratio of 255% was far above the 100% required by the Ministry of Finance (JP, 10/4/04). Against this background, the case was clearly reminiscent of the tribulations in 2002 of the Manulife insurance company (Athukorala 2002), which was sued and declared bankrupt on the spurious grounds that it had failed to pay a dividend. Fortunately, both cases had a similar ending: the bankruptcy declarations were overturned on appeal. In the Prudential case, the Supreme Court argued that the Commercial Court should have referred the case to a regular district court for adjudication as a matter of contract law, rather than trying it as a bankruptcy case (JP, 9/6/04).

If a company is declared bankrupt, it is put into the custody of a receiver, whose charge presumably is to protect asset value for the sake of all creditors. In the Prudential case, however, the receiver appointed was apparently a former partner of the lawyer for the plaintiff, and was no longer a member of the Indonesian Association of Receivers. There was thus an implicit threat of destruc-tion, rather than preservadestruc-tion, of asset value; this could put great pressure on a company, even while it awaited the outcome of an appeal of a court decision.

Under the 1998 bankruptcy law, a company with at least two creditors, and delinquent in payments to at least one, may be declared bankrupt. It is now pro-posed that the bankruptcy law be amended so as to restrict the filing of bank-ruptcy petitions against insurance companies to the Ministry of Finance, the body that oversees the industry, in line with existing arrangements for banks and finan-cial services companies (Kuntjoro-Jakti 2004). This seems a reasonable step under the circumstances. A more controversial question is whether the bankruptcy law should contain a solvency test, which would allow additional judicial discretion

in bankruptcy decisions. It is debatable, for example, how to value the ‘good will’ that a company has accumulated. In any case, Schröeder-van Waes and Sidharta (2004) find that diminished confidence in the bankruptcy law is related primarily to corruption of the legal process rather than to problems of judicial competence or the structure of the law itself.

The Tri Polyta Petrochemical Case

A further blow to the justice system’s international reputation came with a deci-sion by a district court to annul a bond agreement between the petrochemical company PT Tri Polyta Indonesia and its foreign creditors (Asian Wall Street Journal, 13/5/04). Tri Polyta is Indonesia’s largest manufacturer of polypropylene resins. Although the company is listed on the JSE and was previously listed on the New York Stock Exchange, a large stake is owned by business tycoon Prajogo Pangestu.

A US federal district court in April 2003 had ordered Tri Polyta to repay credi-tors $310 million in principal and interest on a $185 million bond that Tri Polyta had issued in 1996 and that was underwritten by US investment banks. However, the company counter-sued in a district court in Banten province, which ruled on 12 May that the bond was illegal under Indonesian law, and thus that the com-pany was not obliged to repay. For the loan agreement, Tri Polyta had established an offshore company in the Netherlands, under a tax treaty between Indonesia and the Netherlands, in order to reduce the Indonesian income tax liability on the interest to be paid. It was on this basis that the loan agreement was annulled. Parties knowledgeable about the case suggest that, although there may be a pub-lic popub-licy issue as to whether the tax treaty is advantageous to Indonesia, the loan agreement was in fact consistent with applicable Indonesian law.

The case was complicated by the disparate interests of the foreign bond hold-ers, underwriters and other defendants. For example, the underwriters primarily wanted to be exempt from any liability, while the bond holders additionally wanted to recover the principal plus interest on the loan. For their part, the bond holders might have made it harder for the court to rule in favour of Tri Polyta, or at least laid a stronger basis for appeal, had they counter-claimed for repayment of the funds on the principle that Tri Polyta was at least as responsible for the questionable arrangements as any other party, and was unjustly enriched by the annulment of the loan agreement. In any event, Tri Polyta did not win all aspects of the case. Its demands for the return of $43 million in payments made on the bond in 1997 and 1998, and for the payment of $100 million in compensation for lost business and $500 million for emotional distress to company management (Bloomberg, 9/4/04), were rejected by the court. It is not clear whether either side will appeal the verdict.

Broader Considerations

The broader problem that underlies both of these cases is that legal certainty is a public good, and as such is subject to free riding. Individuals who see an oppor-tunity to exert leverage over other parties to their own benefit, even in the absence of a legitimate dispute, will pursue their own interest to the detriment of the reputation of the nation as a secure and hospitable business environment. Pursuit of those interests in a legal system as weak as Indonesia’s presents few

problems to unscrupulous individuals, particularly because Indonesian law con-tains no sanctions against malicious or frivolous litigation. For their part, judges in lower courts in particular perceive their salaries to be low, lack technical and other resources, may believe other judges to be corrupt, and may not have a full appreciation of the ramifications of their decisions. Moreover, under Indonesia’s civil law system, judges are not required to abide by precedents established in prior cases in higher courts, as is the case under a common law system.

One of the unfortunate consequences is that the outlook for foreign direct investment in Indonesia will remain bleak; Indonesia had a $14.1 billion cumula-tive net outflow of foreign direct investment from the last quarter of 1997 through the third quarter of 2003, though some recent quarters have shown very modest net inflows. Moreover, Indonesian companies that consistently act in good faith may have to pay higher interest rates on their loans, or may not be able to obtain credit at all. On the other hand, in the absence of formal institutional mechanisms that will fairly enforce contracts, private arrangements can be expected to emerge to fill the vacuum. Repeat dealing between parties and concerns about corporate reputation can provide a market-based discipline—or organised crime may pro-vide its own form of contract enforcement services. Also, Indonesian companies that have offshore assets that can credibly serve as collateral may have better access to foreign credit, since these assets are presumably beyond the reach of Indonesia’s legal system, which the companies might otherwise be tempted to exploit.

NOTES

1 In the 1999 general election, PDIP gained 157 of the 500 seats in the DPR, and Golkar 120.

2 If any pair of candidates captured at least 50% of the national vote plus at least 20% of the vote in half of the provinces in the first round, there would be no run-off election. 3 The countries included in the REER calculations for figure 2 were the US, Japan, Germany, France, the UK, the Netherlands, China, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Korea, India, the Philippines and Vietnam. Total trade weights (the sum of exports and imports, with oil and gas included) for 2000 were calculated using data from the CEIC Asia Database. The included countries accounted for 76.4% of Indonesia’s trade in 2000.

4 The indicative targets for base money at the end of 2002 and 2003 under the relevant letters of intent to the IMF implied base money growth of 6.1% in 2003. Actual growth, at 20.4%, was far in excess of this.

5 McLeod (2004) calls for a radical reassessment of how bank failures should be man-aged so as to avoid such losses, observing that deposit insurance leads to significant moral hazard in a weak regulatory and legal context.

6 Under Law 25 of 1999 on the Fiscal Balance between Central and Regional Govern-ments, the central government retains 85% of crude oil revenues and 70% of natural gas revenues. Thanks to their powerful separatist movements, however, the special autonomous provinces of Aceh and Papua now receive 70% of their respective oil and gas revenues and the central government only 30%.

7 Daily data on the Singapore spot gasoline price are from US Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/international/Gas2.xls. Daily exchange rate data are from the Pacific Exchange Rate Service at the University of British Columbia, fx.sauder.ubc.ca/data.html.

8 On 1 March, Pertamina raised the prices of the less subsidised premium gasolines Pertamax and Pertamax Plus by 6.5% and 5.8%, respectively.

9 The failure to develop clear implementing regulations for the Oil and Gas Law of 2001 is one of the impediments to new investment; state enterprise Pertamina no longer has regulatory authority, but its new role in the oil and gas sectors is not yet clearly defined. However, the World Bank (2004) notes that 15 new oil and gas contracts were signed in 2003, compared with only one in 2002.

10 This includes personal income tax revenues obtained under article 21 (on withholding tax) and article 25 (on end-of-year tax) of Law 17 of 2000 (the current income tax law), as well as those included under personal income taxes of a final nature (on honoraria) and collected from taxpayers leaving the country to travel abroad (fiskal luar negeri). Separate data are not available for fiskal luar negeri; since it is creditable against other personal income tax obligations, I include it in the total.

11 The current personal income tax rate structure includes marginal rates of 5, 10, 15, 25 and 35%.

12 Decree No. 486/KMK.03/2003 (30 October 2003). This is a more workable version of a 2002 fiscal stimulus measure under which the government bore the taxes on labour income up to the regional minimum wage.

13 I estimate that, if Indonesians reported to the tax authorities all the income they reported to Susenas officials, application of the income tax law would yield Rp 143.9 trillion in personal income tax revenues in 2004, rather than the predicted Rp 47.9 tril-lion mentioned earlier.

14 Because the 2003 decree would be superseded by the proposed income tax changes, I apply the estimated percentage decrease to the sum of the Rp 47.9 trillion in personal income taxes budgeted for 2004 and the Rp 2.2 trillion in revenues lost under the 2003 decree (as if the 2003 decree were withdrawn first). I then subtract the revenues lost under the 2003 decree from this product to obtain a net budgetary cost relative to the current budget.

15 Bird notes that higher wage earners appear better able to avoid paying into Jamsostek. The reported average monthly wage of workers in the Jamsostek scheme in 2000 was Rp 399,000, well below the average urban wage of Rp 490,000 and the average national wage of Rp 430,000 as reported in the National Labour Force Survey for that year. 16 Decree of the Minister of Industry and Trade No. 643/MPP/Kep/9/2002 (23

Sep-tember 2002), on sugar trade regulation.

17 Decrees 61/MPP/Kep/2/2004 (17 February 2004) and 334/MPP/Kep/5/2004 (11 May 2004).

18 Decree of the Minister of Industry and Trade No. 70/MMP/Kep/2003 on the Supply and Distribution of Subsidised Fertiliser for the Agricultural Sector (11 February 2003). Fertiliser distribution had been deregulated in 1998 under a package of reforms nego-tiated with the IMF.

19 Decree of the Minister of Industry and Trade No. 306/MPP/Kep/4/2003 (17 April 2003).

20 Decree of the Minister of Agriculture No. 107/Kpts/SR.130/2/2004 (13 February 2004). 21 Previously warned producers that failed to comply with the regulations could have their fertiliser subsidy withheld. Distributors and retailers that did not comply could have their trade licences withdrawn (Decree of the Minister of Industry and Trade No. 356/MPP/Kep/5/2004, 27 May 2004).

REFERENCES

Alisjahbana, Armida S., and Chris Manning (2002), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’,

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies38 (3): 277–305.

Arifianto, Alex (2003), ‘Indonesia Needs Broader Social Security Scheme’, Jakarta Post, 27 June.

Arifianto, Alex (2004), ‘Proposed Indonesian Social Security Reform: Will It Work?’, Jakarta Post, 31 January.

Athukorala, Prema-chandra (2002), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies38 (2): 141–62.

Bird, Kelly (2003), The Proposed Social Security Program Law, Unpublished paper, Growth through Investment and Trade (GIAT) Project, USAID and Republic of Indonesia.

Kenward, Lloyd R. (2004), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies40 (1): 9–35.

Kuntjoro-Jakti, Dorodjatun (2004), ‘Indonesia Trade and Investment Summit: Oppor-tunities in a Rising Democracy’, Speech by the Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs, Republic of Indonesia, 19 May, London.

McLeod, Ross H. (2004), ‘Dealing with Bank System Failure: Indonesia, 1997–2003’,

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies40 (1): 95–116.

Manning, Chris (2004), ‘Labour Regulation and the Business Environment: Time to Take Stock’, in M. Chatib Basri and Pierre van der Eng (eds), Business in Indonesia: New Challenges, Old Problems, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Marks, Stephen V. (2003), ‘Personal Income Taxation in Indonesia: Revenue Potential and Distribution of the Burden’, Partnership for Economic Growth, USAID and Republic of Indonesia, June, www.pegasus.or.id/public.html.

Marks, Stephen V. (2004), ‘Fiscal Sustainability and Solvency: Theory and Recent Experience in Indonesia’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies40 (2), in this issue. Ministry of Finance (2004), ‘Reforming the Indonesian Tax System’, Presentation to the

Investment Working Group of the Consultative Group on Indonesia, Jakarta, May. Schröeder-van Waes, Marie-Christine, and Kevin Omar Sidharta (2004), ‘Upholding

Indonesian Bankruptcy Legislation’, in M. Chatib