Waci Speakers in Togo and

Benin

A Sociolinguistic Survey

A Sociolinguistic Survey

Gabriele R. Faton

SIL International

®2018

Electronic Survey Report 2018-003, March 2018 © 2018 SIL International®

SIL personnel conducted a sociolinguistic survey in the Waci language community (Kwa language family) of the Republic of Togo and the Republic of Benin in 2002, and the report was written in October 2006. Waci is part of the Gbe language continuum and is related to both Ewe and Gen.

The researchers conducted informal interviews with various subjects and administered

questionnaires to village chiefs, elders, and others. By these means they collected data concerning the geographic location of the Waci language area, the comprehension of Ewe and Gen by the Waci

population, language use patterns, language vitality, language attitudes toward the use of Ewe and Gen, attitudes toward Waci language development, the religious situation, language use in the religious domain, and the state of nonformal education in the language area.

Results of the interviews indicate that the Waci in Togo have a high level of comprehension of both Ewe and Gen. They identify with the Ewe people and display overtly positive attitudes toward the use of Ewe. In contrast, attitudes toward the use of Gen are overtly negative.

In Benin the Waci have a high level of comprehension of Gen, whereas comprehension of Ewe appears to be low. Attitudes towards the use of Gen are overtly neutral, whereas attitudes towards the use of Ewe were not investigated.

This survey report written some time ago deserves to be made available even at this late date. Conditions were such that it was not published when originally written. The reader is cautioned that more recent research may be available. Historical data is quite valuable as it provides a basis for a longitudinal analysis and helps us

iii

5.1 Informal interviews with linguists and church workers 5.2 Questionnaires for traditional leaders and religious leaders 5.3 Questionnaires for literacy coordinators

6 Results

6.1 Waci language varieties

6.2 Comprehension of Ewe and Gen 6.3 Waci language vitality

6.4 Language attitudes

6.4.1 Attitudes towards the written development of Waci 6.4.2 Attitudes towards the use of Gen and Ewe

6.5 Literacy

6.5.1 Classes offered

6.5.2 Motivation for literacy

6.5.3 Difficulties in literacy programs 6.6 Language use in the religious domain

6.7 Ethnic identity, group cohesion, and social relationships

7 Summary and conclusions

7.1 Comprehension of Ewe and Gen 7.2 Language vitality

7.3 Language attitudes 7.4 Literacy

7.5 Ethnic identity, group cohesion and social relationships

8 Recommendations

Appendix A: Maps of the Waci language area Appendix B: Lexical similarity

1

A sociolinguistic survey was conducted among the Waci1 language community of the Republic of Togo

and the Republic of Benin in February and March 2002 by Gabriele Faton and Katharina Wolf,

researchers from the Togo-Benin branch of SIL International2 (SIL Togo-Benin). It was supervised by Dr.

Deborah H. Hatfield. The survey is part of a larger study of the Gbe communities of Togo and Benin and is designed to provide the administrators of SIL Togo-Benin with information about the Waci language area in order to determine the need for SIL involvement in Waci language development and the priority and strategy for such involvement.

We include in this report survey data derived from individual interviews and interviews with government officials3 in the sub-prefecture of Comè,4 the sub-prefecture of Grand-Popo, Benin, the

prefecture of Yoto, Togo and the sub-prefecture of Afanyan, Togo. The researchers also interviewed community leaders in the villages of Oumako (sub-prefecture of Comè, Benin), Ahépé (prefecture of Yoto, Togo) and Atitogon (sub-prefecture of Afanyan, Togo).

In the Introduction (section 1) we present pertinent background information gathered during preliminary research and during field interviews with members of the Waci language community. Subsequent sections contain information on previous linguistic research, the research questions, and a description of the assessment techniques used in this survey. Next, we discuss the results of the interviews, both formal and informal. The report ends with a summary, conclusions, and recommendations, followed by appendices and references.

We are grateful to the local authorities and citizens for the authorization and assistance that made this research possible.

1.1 Language and classification

Williamson and Blench (2000:18) have classified the Kwa language group as follows: Proto-Niger-Congo, Proto-Mande-Atlantic-Congo, Proto-Ijo-Congo, Proto-Dogon-Congo, Proto-Volta-Congo, East Volta-Congo, Proto-Benue-Kwa, Kwa. From pers. comm., they also cite Stewart’s (1989) revised and then current classification of the Gbe language group: Proto-Kwa (New Kwa), Gbe.5 According to his interpretation of

linguistic evidence, Stewart divides the Gbe language cluster into two branches: Fon-Phla-Phera on the one hand and the two subgroups—(a) Ewe and Gen and (b) Aja—on the other hand (Williamson and Blench 2000:29).

Dr. Hounkpati B. C. Capo, an expert on the Waci language family (1986:101), (see section 5.1) divides the Gbe languages into five groups: Vhe (Ewe), Gen, Aja, Fon, and Phla-Phera (Xwla-Xwela). He puts Waci in the Vhe (Ewe) group, together with Towun, Awlan, Gbín, Peci, Kpando, Vhlin, Ho, Avɛ́no, Vo, Kpelen, Vɛ́, Dayin, Agu, Fodome, Wancé, and Adángbe.

1 In general, language names are spelled using the English alphabet.

2 SIL is affiliated with the Direction de Recherche Scientifique in Togo and with the Centre National de Linguistique

Appliquée in Benin. It has been accorded nongovernmental organization status in both countries. 3 See Appendix C for questionnaires which correspond to the various interviews.

4 Place names are spelled according to maps of Togo and Benin (Institut Géographique National 1977; 1992), where

possible. At the time of the survey, Benin was divided into twelve governmental provinces called départements, each of which was composed of a varying number of sub-prefectures, which encompass various communes (rural

communities and urban districts). The départements were reorganized in 1999. With decentralization in 2002, sub-prefectures became communes and communes became arrondissements. Togo consists of five provinces (régions). Each province is divided into a varying number of prefectures and sub-prefectures.

Alternative spellings of the language name are Watyi, Wotsi, or Ouatchi (Capo 1986:13). Interviewees in villages in the language area unanimously referred to their language as Waci [watʃi].

1.2 Language area

Waci villages are located in southeastern Togo and in southwestern Benin. For maps of the area, see Appendix A. Because of the migration pattern of the Waci people (see section 1.6), most Waci live in southeastern Togo.

According to the language map of Benin (CENALA 1990) and the Atlas sociolinguistique du Bénin (CNL du Bénin 1983:67f.), Waci villages in Benin are located in the département of Mono. According to the Atlas, Waci is spoken in the following places, listed in order from north to south:

• the sub-prefecture of Athiémè: Ahoho and Dedokpo

• the sub-prefecture of Comè: Comè (the whole urban community and rural district) and in the rural community of Oumako

• the sub-prefecture of Grand-Popo: Dévikanmè, Vodomè and Sazué in the Djanglanmè rural

community and Kpovidji, Todjohounkouin, Sého-Condji, Gbéhoué-Ouatchi and Sohon in the Adjaha rural community.

This information was confirmed by Capo (pers. comm.) and others. Capo further indicated that these areas are also Waci-speaking: two villages within the rural community of Dedokpo6; the villages of

Atitoedomin, Tala7 and Agoutomè (southeast of Comè); and Dimado8 I and II and Kpablè (west of

Gbéhoué-Ouatchi).

According to certain sources, the borders of the Waci language area in Togo are roughly the line between Gboto Zévé and Tokpli to the north, the Mono River to the east, the line between Vogan and Aklakougan to the south and within the vicinity of Tsévié to the west. This information was confirmed during interviews with community leaders in the language area and refined as follows. The villages north of the line between Gboto Zévé and Tokpli up to the classified forest of Togodo are Aja villages. It is not quite clear whether Tokpli, a village that was founded by the Germans during their colonial rule, is a Waci village, as there is a significant presence of other ethnic groups such as Aja, Ana (Ifè) and Gen there. The line between Vogan and Aklakougan is only a rough approximation of a border of the language area to the south. Because people move around and mix, there is no clear-cut border between Waci and Gen areas. Vogan is a Waci village with a mixture of ethnic groups. In the area around Aklakougan, Waci speakers seem to be mixed mostly with speakers of Gen, but also with Fon and Kotafon speakers. Waci villages extend west as far as the Haho River. Sources disagreed as to whether the villages between the Haho River and Tsévié are Waci- or Ewe-speaking. The languages do not change abruptly, but blend into each other.9 This is reflected in the frequent use by people in the language area

in Togo of the terms “Waci” and “Ewe” interchangeably to designate their own language.10 Therefore, in

Togo it is impossible to determine clear-cut language borders between Waci, Ewe, and Gen.

6 The names of these villages are unknown to the author. 7 Atitoedomin and Tala are not indicated on the map. 8 Dimado is also considered part of Sohon.

9 As one person in Tabligbo reported, “In Comè they speak like we do, but they mix it with Fon. In Tsévié it is Waci,

but it tends towards Ewe. …Afanyan is already a bit mixed (with Gen).”

1.3 Presence of other ethnic groups

Waci villages are situated in an area bordered by Aja to the north, Saxwe to the northeast, Xwela to the east and southeast, Xwla to the south, Gen to the south and southwest, and Ewe to the southwest and west (CENALA 1990).

Not only are the borders of the Waci language area fuzzy, but also villages of different ethnic origins are mixed together inside the area. For instance, between the Mono and Sazué Rivers in Benin, there exist Kotafon and Aja villages along with the Waci villages of Dedokpo and Ahoho (Hatfield, Henson and McHenry 1998; Capo, pers. comm.). Within the Waci area in Togo, there are Aja-Talla villages along the Mono River, Aklobo villages11 along the Haho River and north of Tabligbo, and an Ana

(Ifè) village between the Waci and Aja language areas.

Waci villages are generally not isolated from contact with other ethnic groups, because these groups are present in major towns and Waci speakers and members of other ethnic groups intermarry. In addition, there is vibrant commercial traffic in the area.

The major towns in the language area—such as Comè, Benin and Tabligbo, Togo—are melting pots of various ethnic groups. In Comè the majority of the population is Waci, but Gen, Fon, and Aja speakers are also present, as are Hausa and Yoruba, who live in the part of town called Zongo12 (Capo, pers.

comm.). Tabligbo, the seat of the prefecture of Yoto, is not a traditional Waci town. It was founded for administrative and logistical purposes, and the population includes people of Ewe, Gen, and Aja origins. There is a “mosaic of languages” according to inhabitants of Tabligbo.

The Waci villages we surveyed claim to be monolingual, and indeed the majority of Waci men marry Waci women. However, marriages between Waci speakers and Ewe, Gen, Aja, and also some Kotafon and Kotokoli speakers were reported.

1.4 Regional language use

Waci is the main language spoken by the Waci people. The languages of wider communication are Ewe and Gen. Ewe (and its varieties) is widely used generally in the south of Togo and is also taught at school. Gen, also called Mina,13 is used throughout the southeast of Togo and the southwest of Benin. It

is considered to be the easiest language “for all Ewe peoples” according to the Gen linguist interviewed, and “the best understood in the region” according to the Waci linguist interviewed (see section 6.2). Both Ewe and Gen are used particularly in the bigger markets and for communication between the different ethnic groups present in the area. French is the language of the formal education systems in both Togo and Benin.

In the Waci language area in Benin, the government literacy organization Direction Nationale de

l’Alphabétisation et de l’Education des Adultes (DNAEA), nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and

churches organize literacy classes in Aja, Gen, Kotafon, Saxwe, and Xwela, as well as in a combination of Gen and Waci.14 In Togo nonformal education in local languages is primarily offered by churches and

NGOs in Ewe or French in the south and in Kabiye in the north.

Churches in the Waci language area use Waci, Ewe, Gen, and French in their worship services. Bible readings are usually done in either Ewe, Gen, or French. The official language in the Catholic Church in the Waci area is Ewe in Togo and Gen in Benin (département of Mono).

11 These are Ghanaian settlements.

12 Zongo is the name given to the settlements of Muslim traders in or on the outskirts of a town.

13 In everyday speech, Gen is often referred to as Mina. The term originated from Portuguese colonial times, but the

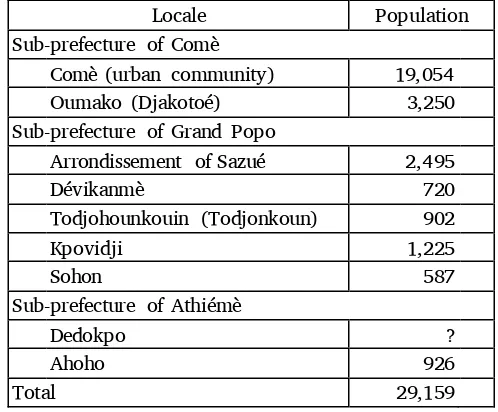

1.5 Population

The 1992 Benin census (Ministère du Plan 1994a:11), which cites population statistics both by ethnic group and political community, gives a Waci population of 30,005. The 2002 Benin census (Ministère

Chargé du Plan 2003a) gives a Waci population of 36,574, or 0.5 percent of the Beninese population. It

should be noted that during both censuses, individuals were asked to which ethnic group they belonged and not which language they spoke as their first language. Thus, interviewees identified themselves as belonging to their father’s ethnic group, even though they may neither have spoken his language nor lived in that language area. When we tally population figures from the census for villages identified by interviewees as Waci-speaking, we get the following figures for 1992 and 2002 (Ministère du Plan 1994b;

Ministère Chargé du Plan 2003b):

Table 1. Benin 1992 census: Population of Waci-speaking locales

Locale Population

Table 2. Benin 2002 census: Population of Waci-speaking locales

Locale Population

Some sources give Waci populations of up to 110,000 in Benin and 365,500 in Togo (Grimes 2000; Joshua Project 2000). These figures, compared to the estimates based on census data in tables 1 and 2, are too high, at least for Benin.

1.6 History of migration

The Ewe king Agokoli reigned in Notsé (Togo) at the end of the sixteenth century. When conflicts arose between him and his counselors as well as with the population, a large percentage of the population fled. Those who left split into three groups and dispersed to the south, the southwest and the northwest. Others from Notsé set out in search of land at a later stage with Agokoli’s consent. The Waci were basically a subgroup of the southern group, which was dominated by the Dogbo and related lineages. Some traditions maintain that they left Notsé after the main diaspora as a result of a famine (Gayibor 1996:86–91; Pazzi 1979:97–102).

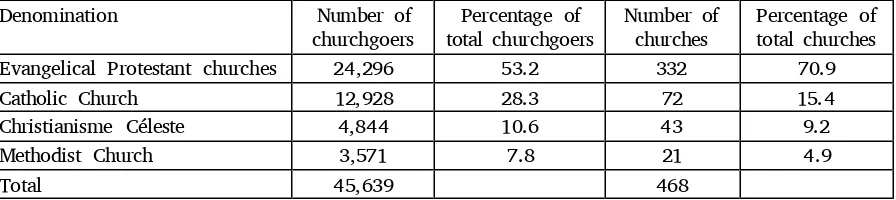

1.7 Religion

The next three sections present details on traditional religion, Christianity, and Islam.

1.7.1 Traditional religion

The traditional religion of the Waci is polytheistic. In the département of Mono, Benin, traditional religion is the main religious force—74.2 percent of the population practice traditional religion, compared to a national average of 35 percent (Ministère du Plan 1994a:12, 15). This was confirmed by church leaders in Oumako (sub-prefecture of Comè, Benin) who, when interviewed during this survey, stated that the majority of the inhabitants practice traditional religion.15 No statistical data were

available for Togo. Information gathered during the survey in Togo is ambiguous; according to one church leader, the majority of the population in Ahépé (prefecture of Yoto, Togo) practice traditional religion, whereas the village chief of Ahépé maintains that the majority is Catholic.16 In Atitogon

(sub-prefecture of Afagnan, Togo) the majority of the population is also reported to be Catholic. It is possible, though, that the influence of traditional religion in the language area in Togo is similar in strength to its influence in Benin.

1.7.2 Christian churches

The Waci villages in Benin are all situated in the département of Mono. Table 3 shows the proportions of evangelical Protestant churches and other denominations (ARCEB 2001a:93).

15 The village chief said the majority of the inhabitants were Christian, but the church leaders’ evaluation seems

more probable in light of the census data.

Table 3. Christian churches in the département of Mono (Benin)

Evangelical Protestant churches 24,296 53.2 332 70.9

Catholic Church 12,928 28.3 72 15.4

Christianisme Céleste 4,844 10.6 43 9.2

Methodist Church 3,571 7.8 21 4.9

Total 45,639 468

According to ARCEB, in forty-one churches the majority of the members are Waci, and in sixty-seven churches Waci are present as the largest, second largest, or third largest group (ARCEB 2001b).

In Oumako (sub-prefecture of Comè) the following churches were reported to be present:

Assemblies of God, Christianisme Céleste, Deeper Life, Mission Evangélique de la Foi, New Apostolic Church,

Parole du Christ au Monde, Pentecostal Church, Roman Catholic Church, and Union Renaissance d’Hommes

en Christ. All of the Christians in Oumako are reportedly Waci. The Catholic Church is the largest church,

followed by the Assemblies of God.

A comprehensive list of churches in the Waci language area of Togo was drawn up by IMB17

workers. They noted the presence of the following denominations: Union Baptiste, Assemblies of God, Baptistes du Plein Evangile, Bethesda, Christianisme Céleste, Church of Christ, Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Methodist Church, Gradinski’s Church, Mission Chrétien, the Pentecostal Church of Togo, the Presbyterian Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Seventh Day Adventist Church. IMB workers found that the largest denominations in the area are the Baptists (with seventeen parishes), the Adventists (fourteen) and the Catholic Church (eight).

In Ahépé these denominations are reportedly present: the Apostolic Church (two different

branches), ARS, the Assemblies of God, the Baptist Church, La Bonne Nouvelle, Christianisme Céleste, the Church of Christ, Deeper Life, the New Apostolic Church, the Pentecostal Church, the Methodist Church, and the Roman Catholic Church. The religious groups Baha’i and Eckankar were also mentioned. The majority of Christians in Ahépé are Waci. The Catholic Church is the largest church, followed by the Assemblies of God.

In Atitogon the following denominations are said to be present: Aladura, ARS, the Apostolic Church, Assemblies of God, Church of Christ, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jésus est Vivant, the Methodist Church, the New Apostolic Church, Le Nouveau Testament, the Pentecostal Church, La Porte du Ciel, the Presbyterian Church, the Roman Catholic Church, the Seventh Day Adventist Church, and Eglise en Mission pour le

Salut. According to the leaders of the four churches surveyed, the majority of members in the Eglise en

Mission pour le Salut and in the Presbyterian Church are Waci. No such data were recorded for the

Assemblies of God and Aladura, but as the majority of people in the village are Waci, it seems likely that the majority of church members are also Waci. The Catholic Church is the largest church in Atitogon.18

Christian mission groups working in the language area are the IMB (Baptist) and the Church of Christ.

1.7.3 Islam

Islam has a growing influence in the Waci area. Financial aid from abroad has enabled mosques to be built even in villages with no Muslim adherents. As for Muslim presence in the villages visited during the

17 International Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention.

field trip, there are reportedly no Muslims in Oumako. Neither is there a mosque. In Ahépé there is a mosque where the majority of those who pray are Waci. Atitogon has a mosque where about sixty believers, most of whom are Waci, pray.

1.8 Literacy and Waci language development

In Benin the overall literacy rate for both genders and all age groups was 28.6 percent in 1992. More men are literate than women, and the literacy rate is also higher in urban areas than in rural areas. In the département of Mono, these rates were lower than the national average—the overall literacy rate was 21.8 percent (Ministère du Plan 1994a:17–24).

Table 4. Literacy rates in Benin

Age <6 years 6–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 25–29 30+ All ages Male 5.5 39.3 57.5 55.8 55.0 43.0 20.1 34.0 Female 3.0 8.4 24.8 18.8 14.1 9.3 3.5 10.8 Total 4.3 29.5 43.1 37.5 30.0 21.7 10.6 21.8

In order to increase literacy rates, the government literacy body DNAEA organizes and coordinates literacy classes in the local languages throughout the country. In the département of Mono, classes are held in Aja, Gen(-Waci), Kotafon, Saxwe, and Xwela.

Because of the estimated intelligibility of 95 percent between Waci and Gen in Benin, the Gen primer is used for both language groups (Capo, pers. comm.). Its three volumes are entitled Programme d’Alphabétisation: Lecture et Ecriture en Guin ‘Literacy Program: Reading and Writing in Gen’ (Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, Direction de l’Alphabétisation, n.d.). The primer is written in a mixture of Gen and Waci (Capo, pers. comm.), and people in the language area usually refer to it as the Waci-Gen primer.

Efforts are underway to publish a Waci primer. One reason this is necessary is that there is a difference in pronunciation and vocabulary between Waci and Gen. Another reason is that, according to Capo and the Beninese government departmental literacy coordinator, the Waci want a primer in their own language, as most of the surrounding language groups have one. The coordinator noted that the manuscript of the new Waci primer was developed in a workshop financed by the NGO Cellule d’Appui aux Activités d’Alphabétisation (abbreviated C3A) and consists of a primer in three volumes and a math book. Another workshop is planned to check the books and prepare them for publication.

There is not an abundance of post-literacy materials in Waci or Gen. The following texts and publications were mentioned by Capo (pers. comm.):

• a collection of proverbs

• a collection of poems in Waci and Gen

• a course in three volumes (on meteorology and other subjects) translated into Waci but unpublished

• the newspaper Akokisɛ (“The Parrot”) in Gen, which sometimes contains articles in Waci, edited by J. Semadegbe, the literacy coordinator of the sub-prefecture of Comè

Broadcasts from Radio Ahémé in Possotomè cover issues for cattle raisers, obituaries, and cultural events in Waci. Listeners also contribute in Waci (Capo, pers. comm.).

In Togo we did not find any literacy statistics. The general impression is that the Waci are highly illiterate, especially in remote areas (east of the road between Aného and Tabligbo).19

In summary, a systematic approach to nonformal education is lacking. Stakeholders in the area are the churches and the NGO Børnefonden, which offers classes in Ewe or French. The Church of Christ church workers noted that the following Ewe primers, the authors of which are unknown, were found in the language area:20

• Gɔmedzegbale (published in Lomé, 1980)

• Agbalẽfiafia kple hehenana. Ametsitsiwo fe dɔwɔfe. Hadomegbenɔnɔ dɔdzikpɔfe gã. Gɔmedzegbalẽ. “Dɔwɔhabɔbɔmenɔlawo le nu srɔm.” Akpa gbãtɔ. (published in Lomé, 1989)

2 Previous linguistic research

The Gbe language continuum has been the subject of much research, especially since the 1970s. Capo began an extensive comparative study of the Gbe language continuum in 1971. His

phonological and morphophonological comparisons were the basis for his doctoral dissertation. Part of this work was later published in Renaissance du Gbe (Capo 1986).

On the basis of phonological and morphophonological characteristics, Capo posits five basic Gbe clusters: Aja, Ewe, Fon, Gen, and Phla-Pherá. He places Waci in the Ewe language cluster together with Towun, Awlan, Gbin, Peci, Kpando, Vhlin, Ho, Aveno, Vo, Kpelen, Ve, Dayin, Agu, Fodome, Wance, and Adangbe (Capo 1986:99ff.). Henceforth, we shall refer to his categorization as “Aja-Capo,” “Ewe-Capo,” etc.

As a result of Capo’s (1986) study, SIL Togo-Benin chose fifty language varieties from the Gbe continuum for the purpose of eliciting word and phrase lists. This work was carried out between 1988 and 1992 and constituted the first phase of a larger study of the Gbe language continuum. The wordlists were analyzed according to prescribed methodology (Wimbish 1989) in order to determine the degree of lexical similarity between varieties (see Kluge 1999).21

Table 5 displays the percentage matrix at the upper confidence limit22 for the Aja, Ewe, and Gen

clusters. It shows the number of lexically similar items as a percentage of the basic vocabulary. The matrix takes into account variance in wordlist comparisons, which is calculated by ignoring morphemes that appear to be affixed but always occur in the same position (Wimbish 1989:59). See Appendix B for the percentage matrix of lexical similarity and for the variance matrix, which shows the range of error for each count.

20 The development agency of the Seventh Day Adventists (ADRA) also uses these primers, among others, for its literacy work in the south of Togo (ADRA, pers. comm.).

21 No results from phrase list analysis will be included in our current study.

Table 5. Percentage matrix at the upper confidence limit Note: Varieties in italics are included by Capo in the Ewe cluster and those in bold in the Gen cluster

(Capo 1986:99ff.).

The results of the wordlist analysis show a degree of lexical similarity of 80 percent or more between Waci and the following languages: Be, Togo, Aveno, Agu, Wance, Wundi, Vo, Anexo, Gen, Agoi/Gliji, Kpesi, Kpelen, Vlin, Gbin, Ho, and Aja-Hwe (Tohoun). Waci and Vo have an outstandingly high degree of lexical similarity at 99 percent. As regards the Aja varieties, lexical similarity to Waci is generally not above 75 percent. However, lexical similarity between Aja-Hwe (Tohoun) and Waci amounts to 87 percent at the upper confidence limit. Lexical similarity between Adan, Awlan, and Waci is found to be relatively low at 75 percent.

Most of the varieties that display a degree of lexical similarity of 80 percent or more with Waci are in Capo’s Ewe cluster. These varieties are Be, Togo, Aveno, Agu, Wance, Vo, Kpesi, Kpelen, Vlin, Gbin, and Ho. However, although Adan and Awlan display a lexical similarity of just 75 percent with Waci, their phonological and morphophonological features prompted Capo to group them, too, in the Ewe cluster. In contrast, Anexo, Gen, and Agoi/Gliji (with a comparatively high degree of lexical similarity with Waci of 85 percent or 86 percent) were grouped in Gen-Capo instead of Ewe-Capo because of their linguistic characteristics. Therefore, even though the wordlist analysis seems to indicate that all

The SIL wordlist analysis did not include the languages Towun, Kpando, Ve, Dayin, and Fodome (members of Capo’s Ewe cluster).

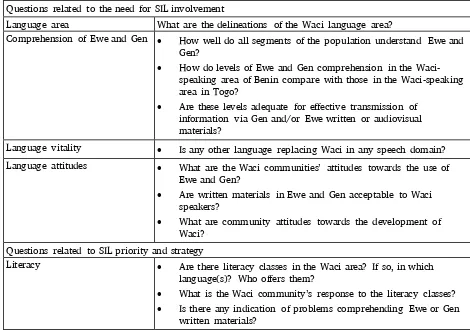

3 Research questions

The purpose of the Waci sociolinguistic survey was to provide the administrators of SIL Togo-Benin with information about the Waci language area in order to determine the need for SIL involvement in Waci language development and the priority and strategy for such involvement. The current SIL Togo-Benin strategy is to promote the use of existing language materials for as many people as possible. That is, written materials will be promoted among first language speakers of a given speech variety and among others who have an adequate comprehension of that variety.

SIL has developed guidance criteria for establishing the need for its involvement in language

development among the language communities in Benin and Togo, and for establishing the priorities and strategies for such involvement. These criteria are divided into two categories. The first includes factors that relate to the need for involvement: dialect comprehension, bilingualism, language vitality, and language attitudes. The second includes factors that influence decisions about language project priority and strategy: group cohesion/identity, existing internal structures or institutions, need/interest expressed by the community, group size, potential community support, religious situation, government programs and policies, relationship to other languages with existing materials, and available or potential resources.

With Ewe and Gen materials already developed and in use in the language area, the main research questions were posed with regard to Ewe and Gen. They are listed in table 6.

Table 6. Research questions

Questions related to the need for SIL involvement

Language area What are the delineations of the Waci language area?

Comprehension of Ewe and Gen • How well do all segments of the population understand Ewe and Gen?

• How do levels of Ewe and Gen comprehension in the Waci- speaking area of Benin compare with those in the Waci-speaking area in Togo?

• Are these levels adequate for effective transmission of information via Gen and/or Ewe written or audiovisual materials?

Language vitality • Is any other language replacing Waci in any speech domain? Language attitudes • What are the Waci communities’ attitudes towards the use of

Ewe and Gen?

• Are written materials in Ewe and Gen acceptable to Waci speakers?

• What are community attitudes towards the development of Waci?

Questions related to SIL priority and strategy

Literacy • Are there literacy classes in the Waci area? If so, in which language(s)? Who offers them?

• What is the Waci community’s response to the literacy classes?

Questions related to the need for SIL involvement

Language development • Which written materials, such as primers, community

development booklets, newspapers, and calendars, exist in Waci?

• Are there radio broadcasts or audiovisual materials, such as audio tapes of music, in Waci?

• Do the stakeholders and leaders of the Waci community consider their linguistic needs to be met by the existing written and audiovisual materials in Gen, Ewe, or Waci that are currently available in the Waci language area?

Language use in the religious

domain • Which languages are used in the religious domain?

Group cohesion and social

relationships •• What is the ethnic identity of Waci speakers? To what extent are the Waci integrated into the surrounding groups?

4 Methodology

We followed the Strategy Formulation Model described by Gary Simons (2000) and placed special emphasis on interviewing resource people from the Waci language area and people working in the area—people such as Gbe linguists and linguistic students, community and church leaders, and literacy coordinators.

4.1 Informal interviews

Informal interviews were conducted with the following people in order to investigate background information:

• linguists working in the Gbe language continuum

• church workers working in the language area

• prefects and sub-prefects23 in the language area

• several other individuals encountered during the survey trips

4.2 Questionnaires

Questionnaires, detailed in Appendix C, were used for interviews with village chiefs and elders, church leaders, and literacy coordinators. They cover the following topics:

• language name(s) and language area

• language use

• language vitality

• language attitudes

• comprehension of Ewe and Gen

• ethnic identity

• religious situation

• literacy situation

5 Implementation of the interviews

The next two sections give details about informal interviews with linguists and church workers, and questionnaires for traditional leaders and religious leaders.

5.1 Informal interviews with linguists and church workers

A Gen linguist shared some insights into the relationships between the Waci and Gen people groups and provided useful contact information.

Dr. Hounkpati B. C. Capo is Waci and a prominent Gbe language continuum scholar. He is a member of the Gen-Waci language subcommission of the Centre National de Linguistique Appliqué (CENALA) of Benin and is the founder of the Laboratoire International des Parlers Gbe (“Labo Gbe”) in Gadomè, Benin. The Labo Gbe houses a documentation center on Gbe languages and publishes papers on the subject.

We interviewed a Waci linguist who wrote his master’s thesis on the syntax of the Waci language and works in the domain of the acquisition of French by adults. He provided information on the extent of the language area, cultural centers, and Waci language development.

We interviewed IMB church workers who have a thorough knowledge of the Waci language area in Togo. In addition to clarifying the extent of the language area, they shared their experiences with the use of written and audiovisual materials in Ewe.

We interviewed two Church of Christ workers who speak Ewe fluently and have lived in Tabligbo, Togo since 1994. Along with their team, they informed us about language use in their work and in the language area in general, and about their perception of levels of comprehension and proficiency of Ewe and Gen among the Waci. Locations for the village interviews were chosen on the basis of the

information they provided.

5.2 Questionnaires for traditional leaders and religious leaders

We attempted to choose representative villages and also to get a geographically balanced sample for interviews with traditional and religious leaders. As the majority of Waci live in Togo, we decided to survey two villages in Togo and one village in Benin.

The Church of Christ workers informed us that on their migration south from Notsé, the Waci in Togo originally settled in the villages of Ahépé, Kouve, Atitogon, Vogan, and Afanyan—the villages from which all future Waci settlements spread out. Out of those five, we chose the following two:

• Ahépé (prefecture of Yoto) is situated eleven kilometers northwest of Tabligbo. In contrast to Tabligbo, with its mixture of ethnic groups, Ahépé is said to be a pure Waci village. However, as it is located on the main road between Tabligbo and Tsévié, it is easily accessible and its inhabitants are probably more exposed to outside influences and to other languages than those in the more remote villages.

• Atitogon (sub-prefecture of Afagnan) is situated eight kilometers south of Afanyan. Being reportedly a pure Waci village, it is sometimes called “the heart of the Waci language area” (Church of Christ workers, pers. comm.). Access is difficult, especially during the rainy season, so that contact with other ethnic groups and languages occurs less often than in villages along the main roads.

When the General Secretary of the prefecture of Yoto heard about these considerations, he approved of our choice.

In contrast, Oumako is reported to be a pure Waci village and was therefore chosen as a site for the interviews. It is situated approximately five kilometers north of Comè and is easily accessible.

During our initial interviews with village chiefs (or délégués), we explained the purpose of our research in their communities. We then asked each of them to set up an appointment for a more detailed interview with themselves and the village elders, and also to invite church leaders present in the village community to participate in the administration of the church questionnaires.

In Oumako, Benin the initial interview with the village chief developed into a full-blown interview guided by the questionnaire, in which the son of the village chief interpreted between French and Waci. An appointment with the church leaders was made for the next day. The church interviews were held in French.

In Ahépé, Togo there are six village chiefs, the main chief being the chef de canton. The interview was conducted with the chef de canton and about fifteen elders. It was not possible to get all the church leaders to one appointment, so we visited them one by one in their homes or churches. As we could not meet with the main priest of the Catholic Church of Ahépé, we interviewed the priest who was present.

Following the interview with the traditional leaders in Atitogon, Togo, the team interviewed the religious leaders of the religious communities present.

During the interviews, the order of the questionnaire items was generally followed, but sometimes the order was dictated by the topic of conversation. The responses were recorded either on the

questionnaires or in note form. A map of the language area (see Appendix A) was used in conjunction with the questionnaire in order to aid in determining language boundaries and to discover which other languages are spoken in the wider area.

A Waci speaker who is a resident of Tabligbo accompanied and assisted the team members in their field research in Togo. He served as a guide and interpreter during the French and Waci interviews.

5.3 Questionnaires for literacy coordinators

In Benin we interviewed two of the three literacy coordinators in the language area—those in Comè and Grand-Popo. As the Waci population in the sub-prefecture of Athiémè is confined to two villages and is rather small, the literacy coordinator in Athiémè was not included in the interviews. The interviews covered information on ongoing nonformal education programs, including languages used for nonformal education classes. In addition, the literacy coordinator of the Mono region gave us useful information on the literacy situation in the Mono region in general and on the effort to publish a Waci primer.

In the Waci language area in Togo, we found little activity in the realm of ongoing literacy programs. Since we were unable to locate anyone doing government-sponsored literacy work, the literacy questionnaire could only be administered to a representative of the NGO Børnefonden, a childcare and development program. In the Waci language area, Børnefonden centers are located in Atitogon (sub-prefecture of Afagnan) and Gboto (prefecture of Yoto).

6 Results

The following sections present the results obtained from informal interviews and from interviews with traditional leaders, church leaders, and literacy coordinators.

When no specific village is mentioned in the discussion of questionnaire results, the term “all interviewees” refers to all persons interviewed in the communities of Oumako, Ahépé and Atitogon. Data contained in the responses to questionnaires are understood to be reported, not tested, even when this is not explicitly stated.

6.1 Waci language varieties

varieties of Waci at 95 percent. Referring to the Afanyan variety in Togo, he states that the intonation is slightly different. Otherwise differences in vocabulary are minimal (Capo, pers. comm.). A Waci linguist observed, “The Waci language of Togo is a bit dialectal. We understand each other, but there are nuances with regard to tones and intonation. Between the Waci language of Comè and that of Togo, there is only a little difference.”

Both the Waci linguist and Capo note minor differences between the varieties of Comè, Gadomè and Oumako in Benin, which are not more than four to eight kilometers apart. “The Waci of Comè differs from the Waci of Gadomè and the two differ from the Waci of Oumako,” stated the Waci linguist. For example, the sound [ts] is used in Oumako where the sound [tʃ] occurs in Gadomè (Capo, pers. comm.).

There are said to be four or five geographical varieties of Waci in Togo, as the inhabitants of each of the five original villages developed a distinctive way of speaking (General Secretary of the prefecture of Yoto and Church of Christ workers, pers. comm.). According to the Church of Christ workers, the pronunciation in Vogan is comparatively glottal, whereas in Tabligbo it is more like Ewe. In Kouve the Waci is most articulated and most like Ewe. The variety from Ahépé is considered to be “grandfather’s language” and people from Vogan laugh at the way people from Ahépé speak. No comment about the Afanyan variety was recorded. The Church of Christ workers state that the differences are often found in idiomatic expressions and in pronunciation.

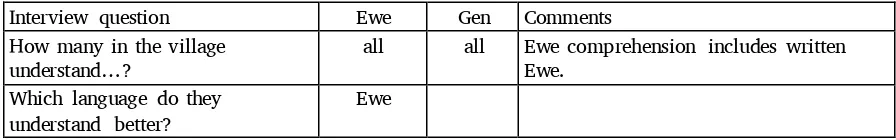

6.2 Comprehension of Ewe and Gen

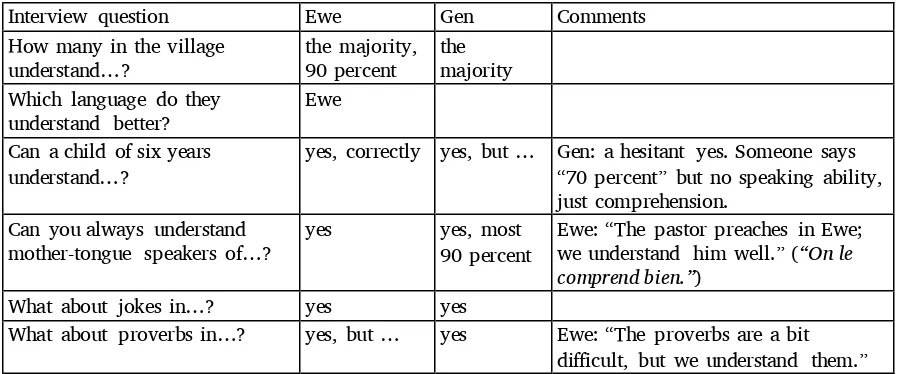

In the village interviews, chiefs and elders were asked about the comprehension of Ewe and Gen by inhabitants of their villages. Tables 7–9 summarize their answers.

Table 7. Comprehension of Ewe and Gen in Oumako, Benin

Interview question Ewe Gen Comments

How many in the village

Can a child of six years understand…? no a little Gen has developed from Waci. (“Le gen estsorti du waci.”)

At what age will it understand…? No answers recorded.

Can you always understand mother-tongue speakers of…?

no yes

What about jokes in…? yes

What about proverbs in…? yes

In Oumako general comprehension of Ewe is reported to be low. Only some people in the village— those who have spent time in Togo—understand Ewe. In contrast, all are said to understand Gen. The interviewee stated that he could always understand everything Gen mother-tongue speakers said, including their jokes and proverbs. However, a six-year-old child in the village is only able to understand a little Gen.

Table 8. Comprehension of Ewe and Gen in Ahépé, Togo

Interview question Ewe Gen Comments

How many in the village understand…?

all all Ewe comprehension includes written Ewe.

Which language do they understand better?

Can a child of six years understand…?

yes yes Ewe even at the age of two. However, children between six and eight years would not understand a text in standard Ewe read to them.

In Ahépé Ewe is understood by the whole population. Even a child of six can understand it, and some said that in fact, “even a child of two could.” The community leaders stated that they could always understand mother-tongue speakers of Ewe, even when they told jokes and proverbs (“Everything”). Similarly, they also understand Gen mother-tongue speakers. However they report understanding Ewe better than Gen. Furthermore, they even know how to write Ewe.24 Children, though, would not be able

to understand readings in standard Ewe, such as from the Ewe Bible. It was usually not quite clear what language variety was being referred to by the term “Ewe.” It might be a mixture of Waci, Ewe, and Gen.

As shown in table 9, in Atitogon the majority of the population understands Ewe, including children of six. The people reportedly understand all that Ewe mother-tongue speakers say, including jokes. Proverbs are said to be a bit difficult, but understandable. The majority also understand Gen, although not as well as Ewe. A child of six also understands some Gen but is not able to speak it. It is reported that people understand most of what a mother-tongue Gen speaker says, including jokes and proverbs. However, Ewe is said to be better understood than Gen.

Table 9. Comprehension of Ewe and Gen in Atitogon, Togo

Interview question Ewe Gen Comments

How many in the village “70 percent” but no speaking ability, just comprehension.

To summarize, in Oumako, reported comprehension of Ewe by the population is low, whereas in the two villages in Togo, Ewe comprehension is reported to be generally high. Only proverbs are rather difficult to understand. It should be kept in mind, though, that the term “Ewe” probably refers to a language variety other than written Ewe. In Togo, Gen comprehension is reported to be fairly high,

though lower than Ewe comprehension. In Benin, Gen comprehension is generally high. However, a child of six in Oumako can reportedly only understand a little Gen. Compared with the respective responses in Ahépé and Atitogon indicating a certain degree of Gen comprehension, this is surprising.

The Church of Christ team in Tabligbo reports that, with the exception of some terms or

expressions, Ewe is generally understood well by all Waci speakers. For example, when they showed the “Jesus” film in Ewe, audience reactions did not seem to indicate any comprehension problems. In another context, however, it was mentioned that older men and women might have some difficulty understanding standard Ewe. Sometimes technical and Biblical terms are the source of comprehension problems. High intercomprehension between speakers of different varieties of Ewe was observed during a training workshop offered by the Church of Christ in Tabligbo. Participants included people from Ewe-speaking areas in Togo, such as Kpalimé. The Church of Christ workers did not observe any hindrances to communication among the participants. On the contrary, the participants interacted with each other in a lively manner and laughed together, indicating that they even understood each other’s jokes.

In contrast, according to the Waci linguist we interviewed, the Waci of Benin do not completely understand “the Togo Ewe,” for they do not study it at school as the Togolese do.

Most Beninese interviewees agreed that Waci is very close to Gen. The Gen linguist said that all Waci understand Gen well. According to Capo (pers. comm.), intelligibility of Gen reaches 95 percent. “The Waci all understand Mina (Gen) 100 percent, even in the remotest villages. In contrast, the Gen do not understand all that the Waci say,” the Waci linguist stated. Here are some comments made:

• “The Waci have accepted literacy classes in Gen-Waci well, because they are closely related

languages (« langues soeurs »), even though the vocabulary is sometimes different. Regardless of age, gender or profession, all Waci understand Gen well.” (Literacy coordinator in Comè)

• “Gen and Waci, that’s the same thing. There are only little differences between them.” (Village chief in Oumako)

• “The Waci have accepted the classes in Gen well, because the Waci and the Mina (Gen) understand each other. Only some expressions, as well as the pronunciation, are different.” (Literacy

coordinator in Grand-Popo)

However, the literacy coordinator of Grand-Popo also reported that some Waci young men and women have comprehension difficulties because of different ways of expression.

As to speaking proficiency, most Waci do not learn Gen systematically. Therefore, the Waci linguist said that when a Waci speaks Gen, he will often be recognized by the typical Waci phonemes he

employs. Others change the phonemes but do not take vocabulary and idiomatic expressions into account (Capo, pers. comm.). Yet the Waci linguist said that it is possible for a Waci to speak Gen without an accent—“pure Mina.”

6.3 Waci language vitality

To evaluate Waci language vitality, we examined domains of language use, the transmission of the language from parents to children, and whether the younger generation is considered to speak Waci correctly.

Concerning domains of language use in Benin, all Waci in the village of Oumako speak Waci. Only those who have traveled might resort to other languages. Waci is used in all the domains of everyday life in the village, in particular for announcements; traditional ceremonies (rites de coutumes); mediation on the family and the village levels; and local and regional meetings of councils of elders (all of which are domains investigated on the community leaders’ questionnaire). In addition, community announcements are translated into Fon, Gen, and French. Regional meetings are held in Waci, Kotafon, Xwela, and French, but not in Gen.

In Ahépé, Togo all Waci in the village speak Waci. Waci is used in all the domains of everyday life, in particular for announcements; traditional ceremonies; mediation on the family and the village levels; and local and regional meetings of councils of elders. During the interview in Ahépé, the chief

Atitogon is a pure Waci village and there are no Waci there who do not speak the language. Waci is used in all the domains of everyday life, in particular for announcements; traditional ceremonies;

mediation on the family and the village levels; and local and regional meetings of councils of elders. When we went to see the chef de canton of Tabligbo, we witnessed a trial. We were told that these sessions are usually conducted in Waci. Tabligbo residents informed us that trials are held in Gen only if foreigners (non-Waci) are concerned.

Thus, it appears that Waci is widely spoken in the Waci villages throughout the Waci language area and also in all the domains of the Waci person’s everyday life. This impression is shared by the Church of Christ workers. In addition, they observed that the Waci always speak Waci with each other and

especially with old men. Even the Waci in Lomé (Togo’s capital city) adhere to Waci. But they develop a mixture of Waci and the Gbe variety spoken in Lomé. In professional settings Waci speak French. In the market they speak Waci where possible. Sometimes they switch to Gen if they speak it well. Otherwise, everyone adheres to the language with which he is most comfortable and is generally understood by the person to whom he is speaking.

Waci is transmitted from parents to children in Oumako, Benin as children learn Waci as their first language. In mixed marriages children learn the languages of both parents. It was not stated explicitly which language they learn first. In Ahépé, Togo, parents speak Waci with their children. In mixed marriages the children learn Waci first, but they understand the languages of both parents. In Atitogon children whose mother or father is Ewe learn Waci first. The children of the pastor of the Presbyterian Church of Atitogon were mentioned as an example. They are Ewe, but they reportedly speak Waci better than Ewe. No answer was recorded for the case of a Gen-Waci family.

Concerning language proficiency among the younger generation, Waci between the ages of ten and twenty in Oumako, Ahépé, and Atitogon were said to speak Waci correctly. Only in Ahépé was it reported that they sometimes make little changes.

To summarize, Waci is spoken in all the domains of everyday life, it is transmitted from parents to children including in mixed marriages, and the younger generation is considered to speak Waci correctly. Therefore, there is no indication that Waci is being replaced by any other language or endangered in any way.

6.4 Language attitudes

Language attitudes towards the written development of Waci and towards the use of Gen and Ewe are discussed in the next two sections.

6.4.1 Attitudes towards the written development of Waci

Interest in Waci literacy was expressed by the village chief of Oumako, Benin and also by the literacy coordinators who were interviewed. The village chief said people would sign up for a literacy program in Waci if it were offered. He also thinks that the best language in which to publish books would be Waci, but the reason he gave was “because if they are in Gen, the book will be in Togo [and not make it to my village].”

The literacy coordinators in the area confirmed the general interest in Waci literacy. They stated that the Waci have a desire for their own primer in Waci, even though the so-called Waci-Gen primer presents no major comprehension problems. The departmental literacy coordinator said, “The Waci want a primer in their own language, as most of the surrounding language groups have one.” According to the literacy coordinator of Comè, however, “Gen serves the Waci best because it is the commercial language and everyone understands it—the Saxwe, the Xwela and the people at church. But the Waci want to introduce literacy in their language, even though they are a minority.” The reason for this might lie in the sense of ethnic identity of the Waci people of Benin and their perception of the Gen: “The Waci prefer the Waci language because they feel dominated by the Gen,” stated the Waci linguist. For more information on ethnic identity, see section 6.7.

village chief of Oumako and confirmed by the fact that efforts to publish a Waci primer are underway. In contrast, church leaders reported that interest was not expressed either in Waci literacy or in religious material in Waci.

As to the village communities surveyed in Togo, interest in Ewe literacy generally dominates in both villages, and there is only some interest in Waci literacy in Atitogon. The group of elders and the village chief interviewed in Ahépé expressed rather strongly that they prefer Ewe to Waci literacy: “We would like to learn how to read and write in Ewe rather than in Waci. We banish Waci. We want Ewe.” If a literacy program were started, people would only sign up for Ewe, not for Waci or Gen.

People in Atitogon said the best language to publish books in would be Ewe. When asked whether they would sign up if a literacy class were started in Waci, Ewe, or Gen, they said “yes” to Ewe and “no” to Gen. No answer was recorded for Waci. However, when asked about Gen they commented, “It’s Waci we are interested in.” Therefore, it seems possible that they would sign up for literacy classes in Waci if they were offered.

In brief, no clear-cut statement concerning interest in Waci language development was made. In interviews with the representatives of the village communities, interest in Ewe literacy dominates, although there is a certain openness to Waci literacy in Atitogon. In the church context, attitudes towards Waci language development appear to be comparatively more positive.

6.4.2 Attitudes towards the use of Gen and Ewe

Waci people in Benin seem to display overtly positive attitudes towards Gen and the use of Gen. As previously mentioned, both the literacy coordinators of Comè and Grand-Popo stated that the Waci have accepted literacy classes in Gen-Waci well and use a Gen primer with Waci as the language of

instruction. The literacy coordinator of Grand-Popo stated, “We would like to have more Waci classes (based on the Waci-Gen primer) in the sub-prefecture, because Waci is the community’s original

language. The Waci want to learn their own language, and not French, Xwela or Xwla, for instance.” This statement reflects the perception that Waci and Gen are the same language. The village chief of Oumako confirmed this impression when he explicitly said, “Gen and Waci, that’s the same thing. There are only small differences between them.” Waci and Gen sometimes are used interchangeably. For example, when we first arrived in Oumako, a young man and an old man showed us the way to the village chief. When we asked them what language they speak in the village, they answered “Gen.” “And Waci?” we asked. “Yes, this is also Waci.” One reason for this might be that the Waci of Oumako do not distinguish rigorously between the terms Waci and Gen in referring to the language they speak. Furthermore, they see themselves as part of the Gen-speaking community. During the interview, the village chief expressed an overtly neutral attitude towards the use of Gen: “If the young people speak Gen at home, the older persons will let them talk and understand them.”

In contrast, attitudes towards Gen and the use of Gen are overtly negative among Waci in Togo. People in Ahépé said, “If the young people speak Gen at home, the older people are sometimes against it because it is Ewe gibberish. It also shows pride.” Similarly in Atitogon, if the young people speak Gen at home, they will be laughed at. Speaking Gen there is also seen as a sign of boasting and pride.

Sometimes people try to speak Gen with a Gen speaker, but according to General Secretary of the prefecture of Yoto, “That’s not good. They have colonized us. The real language is Waci.”

No answers or observations were recorded in Oumako, Benin regarding attitudes towards Ewe and the use of Ewe.

positive, as identification with Ewe appears to be strong. It was stated in Ahépé that “If the young people speak Ewe at home, that’s normal. No one has anything against it.” In Atitogon some said, “The parents will be pleased because the child remembers his origins.”

Thus, among Waci in Benin, attitudes towards the use of Gen appear to be overtly positive. In Togo attitudes towards the use of Gen are overtly negative, whereas attitudes towards the use of Ewe appear to be positive. This pattern is also reflected in the answers to the question of whether people would sign up for a literacy program if it were started in Waci, Ewe, or Gen (see section 6.5.2.).

6.5 Literacy

The next three sections discuss literacy classes offered, the motivation for literacy, and the difficulties encountered in the literacy programs.

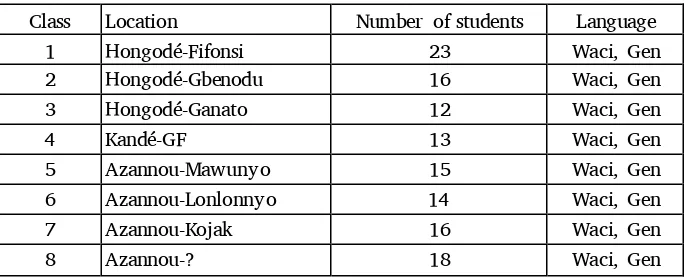

6.5.1 Classes offered

According to the literacy coordinator of the prefecture of Comè, Benin, literacy classes in his sub-prefecture are given by the DNAEA for the Waci in Waci-Gen, for the Saxwe in Saxwe, for the Gen in Gen, and for the Xwela in Saxwe or Gen. Some NGOs also offer literacy classes in Saxwe and Xwela.

All classes currently organized in the area by the DNAEA are in the town (commune urbaine) of Comè. No classes were reported for the rural areas (commune rurale) around Comè. All classes use the Waci-Gen primer, and Waci is the language of instruction.

Table 10. Literacy classes offered by DNAEA in Comè, Benin

Class Location Number of students Language

1 Hongodé-Fifonsi 23 Waci, Gen

According to the literacy coordinator in Comè, the Waci have readily accepted classes in Gen-Waci because the languages are closely related, though some of the vocabulary is different. There are also four post-literacy classes, in existence since 2002, which have a total of about fifty students. As there is nothing written in Waci, the post-literacy classes use Gen materials. These classes present further reading exercises and math.

In Oumako the government-run literacy classes were cancelled because the literacy workers left. (See section 6.5.3 for the reason.) However, there are literacy classes and development initiatives in churches:

• Deeper Life church has a literacy class in Ewe.

• The Catholic Church has a literacy class in Gen with approximately twenty students.

• The Assemblies of God church has literacy classes in French and uses primers in French for this purpose.

• Mission Evangélique de la Foi plans to offer literacy classes in French, but these are not in place yet.

In the sub-prefecture of Grand-Popo, most literacy classes are in Gen. There is one class in

well, because “the Waci and the Mina (Gen) understand each other.” They would like to have more Waci classes in the sub-prefecture. Because the Waci class started in 2002, there is not yet any post-literacy program in existence.

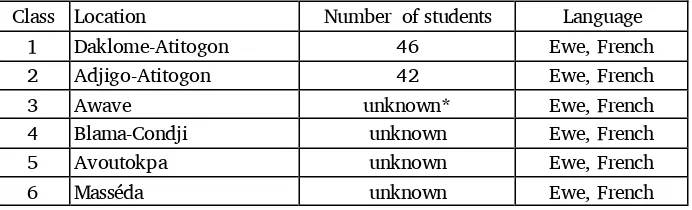

In the Waci language area in Togo, we found literacy programs initiated by NGOs and by churches. In Atitogon the NGO Børnefonden offers six classes for literacy in French. The language of

instruction is Ewe. Four classes were started in March 2002. There is no post-literacy program.

Table 11. Literacy classes offered by Børnefonden in Atitogon, Togo

Class Location Number of students Language

1 Daklome-Atitogon 46 Ewe, French

2 Adjigo-Atitogon 42 Ewe, French

3 Awave unknown* Ewe, French

4 Blama-Condji unknown Ewe, French

5 Avoutokpa unknown Ewe, French

6 Masséda unknown Ewe, French

*The class was started on March 8, 2002. At the time of the interview (one week later), the sign-up process had not been completed yet.

The church leaders in three out of the four churches surveyed in Atitogon see the need for literacy. In the Aladura church there are efforts to teach reading in Ewe, although apparently not on a regular basis. The representative of the Église en Mission pour le Salut (EMS) sees the need for literacy classes, but the church does not have the means to offer any. There was a literacy class in the Presbyterian Church, but when the literacy center in the village opened, the students went there instead.

In Ahépé there are reportedly no literacy classes.

The IMB church workers informed us that in Momé Wdjepe (between Momé Hounkpati and Momé Gbave) the NGO Colombe has a classroom or literacy center. They offer literacy classes exclusively for women. The Seventh Day Adventist church works in community development and literacy in the region. Their development agency, Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA) is based in Lomé. ADRA tried to establish a literacy program in the Préfecture des Lacs, which contains the Waci villages between Aného and Atitogon, but did not succeed. The reasons given were that the target population did not have time and that the ADRA literacy agent stayed only six months in the target village (ADRA, pers. comm.).

6.5.2 Motivation for literacy

Generally it can be said that the Waci community’s motivation for signing up for literacy classes and the success of literacy programs depend on the context and on the target language in which the classes are offered.

In Comè occupational distinctives provided the context for literacy classes that were held in the workshops of seamstresses, hairdressers, and those who process food, and that used primers dealing with professional issues. However, the classes based on this functional method did not catch on (Capo, pers. comm.).

In contrast, some of the literacy classes in churches did succeed (Capo, pers. comm.). This might indicate a higher motivation to learn to read in the church context. This impression was also expressed in Togo. The Church of Christ workers stated that the motivation to learn to read Ewe seems to be rather low unless people want to learn for church purposes. The fact that the churches offer literacy classes or try to do so (see section 6.5.1) also indicates motivation for literacy within the church context. A counterexample of this concerns a literacy class in the Apostolic Church of Ahépé that had to be discontinued because of a lack of motivation (« à cause de la paresse »).

Capo tried to launch a literacy program in Gen-Waci in the fourth level at the collège (high school) in Comè. It was voluntary, and when the students realized that the results did not count towards their overall grades, they quit. He points out, “The people don’t come to literacy classes just to deepen their knowledge. They lack motivation” (pers. comm.). In this particular case, it should be noted that the students are already literate in French. Becoming literate in Gen might not be as attractive to them as it would be to someone who is completely pre-literate.

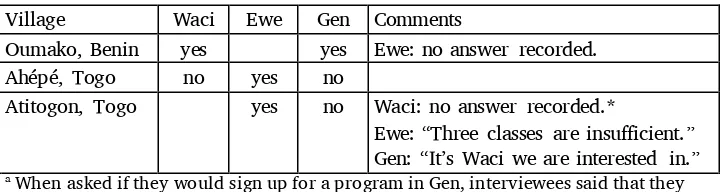

The language in which a literacy class is offered is an important factor in the acceptance and the success of a given literacy program. When interviewees in the villages surveyed were asked whether Waci people would sign up if literacy classes were offered in Waci, Ewe, or Gen, they gave the answers listed in table 12.

Table 12. Acceptable languages for literacy classes

Village Waci Ewe Gen Comments

Oumako, Benin yes yes Ewe: no answer recorded.

Ahépé, Togo no yes no

Atitogon, Togo yes no Waci: no answer recorded.*

Ewe: “Three classes are insufficient.” Gen: “It’s Waci we are interested in.” a When asked if they would sign up for a program in Gen, interviewees said that they prefer Waci to Gen.

Thus, interviewees in the village in Benin expressed motivation for literacy in Gen. In contrast, interviewees in Togo unanimously rejected literacy in Gen but said they would sign up for classes in Ewe. This pattern is in line with overtly expressed language attitudes described in section 6.4.2.

6.5.3 Difficulties in literacy programs

In literacy programs in Gen or Ewe for Waci speakers, comprehension does not seem to be an issue. However, problems arise from various factors: pronunciation differences, orthography, differing

vocabulary and idiomatic expressions, the lack of literacy workers, and the lack of written materials for post-literacy.

In Benin the literacy coordinators of both Comè and Grand-Popo agreed that the Waci have accepted the classes in Gen-Waci well, because the two languages are so closely related. There do not seem to be major problems.

However, sounds and phonemes that are different in Gen and Waci create some reading difficulties. The sound [ə] exists in Waci, but not in Gen. In Waci the word for “man” is ntʃu, whereas in Gen it is nɸu. Similarly, the sound [f] in one language is replaced by [ʋ] in the other. These differences must be taken into account when literacy teachers explain the orthography. Some words and expressions are completely different and must also be explained. Thus, “some young men and women have

comprehension difficulties,” according to the literacy coordinator of Grand-Popo.

In Togo we did not meet any literacy workers who had first-hand information on comprehension and other difficulties experienced by Waci members of Ewe literacy classes.

Another problem is the lack of literacy workers. Lack of financial resources means that literacy teachers usually have to work on a voluntary basis. As soon as they find paying jobs, they leave literacy teaching and new teachers must be found and trained (Capo; Church of Christ workers, pers. comm.). For example, in Oumako, literacy classes were cancelled because the literacy workers left after not having been paid.

6.6 Language use in the religious domain

The languages used for the mass and worship services in the churches in Benin are mainly Gen and French. Waci does not seem to play a major role in regular church services in Oumako. The sermon or homily is usually given in French and translated into Waci or Gen.

In Togo, Waci and Ewe are the major languages used in worship services, the mass and other meetings in the churches surveyed. There are some indications that a mixture of Waci and Ewe is also used (or that the language names “Waci” and “Ewe” are used interchangeably). Gen is only rarely used in one of the villages surveyed.

In all the churches surveyed, the Ewe Bible (1960 edition) is the Bible that is used most often. The Ewe New Testament (1990) was mentioned by three of the church leaders interviewed. In addition, the French Bible (Louis Segond version) is sometimes used.

In the mosques of Ahépé and Atitogon, where mostly Waci believers gather, readings from the Koran and prayers are in Arabic, and the teaching is in Waci.

In traditional religious contexts, Waci is the language that is commonly used by Waci speakers (see section 6.3).

6.7 Ethnic identity, group cohesion, and social relationships

Waci people in Benin and Togo differ markedly with regard to their sense of ethnic identity and their relationship with the Ewe.

In Benin, the Waci have a sense of ethnic identity and a sense of being different from the surrounding groups. They display ethnic pride. This is evidenced by their desire to have their own primer in Waci, even though their comprehension of Gen seems to be high enough to continue literacy classes using the Waci-Gen primer (see section 6.4.1.). As the departmental literacy coordinator points out, “The Waci want a primer in their own language, as most of the surrounding language groups have one.” However, Beninese Waci see themselves as part of the Gen-speaking community. No indications of a particular relationship with the Ewe were noted.

In contrast, Togolese Waci identify strongly with the Ewe. For instance, the representatives of Ahépé, when interviewed, seemed to think of themselves primarily as Ewe who have Waci customs. “We are Ewe-Waci. We will accept being called Waci, as we have Waci customs. But we are all from Notsé (which is Ewe).” This is confirmed by Capo’s statement (pers. comm.) that “the others (the Waci in Togo) say they are Ewe. As for us (in Benin), we are Waci first, and secondly we are Ewe.”

The relationship between the Waci and the Gen is strained on both sides of the language area. The Waci in Benin do not identify with the Gen even though they understand their language well (section 6.2). Capo asserts (pers. comm.) that “the customs of the Gen and the Waci are very different. The Waci names consist of a name that denotes the weekday of the child’s birth and a traditional name. Also the music is very different, although the instruments are almost identical.” The Waci linguist says there are no conflicts between the Gen and the Waci, and the Gen linguist says that they do not have a history of wars as some other ethnic groups do. However, he says the Waci feel dominated by the Gen.

In Togo the Waci people’s attitudes towards the use of Gen are overtly negative. Speaking Gen is seen as a sign of pride or boastfulness (section 6.4.2). The IMB church workers interviewed mentioned that the Waci are known to be very good farmers and look down on the Gen, who buy food from them and “can’t even grow corn.”

Whatever their attitudes, the Waci in Togo and Benin have some social relationships with both Ewe and Gen, as well as with Aja, Fon, Kotafon and Kotokoli, as can be seen by the fact that there are intermarriages with other groups. Intermarriages were reported between Waci and Aja, Fon, Gen, and Kotafon in Oumako, with Aja and Ewe in Ahépé, and with Ewe, Gen, and Kotokoli in Atitogon. In Atitogon the majority of the intermarriages are with Ewe people.