FOR THE

B

WAMU

L

ANGUAGE

W

RITTEN BY: J

OHN ANDC

AROLB

ERTHELETTEContents

0 Introduction and Goals of the Survey

1 General Information

1.1 Language Name and Classification 1.2 Language Location

1.3 Population

1.4 Accessibility and Transport

1.4.1 Roads: Quality and Availability 1.4.2 Public Transport Systems 1.4.3 Trails

1.5 Religious Adherence 1.5.1 Spiritual Life

1.5.2 Christian Work in the Area

1.5.3 Language Use Parameters within Church Services 1.6 Schools/Education.

1.6.1 Types, Sites, and Size of Schools 1.6.2 Literacy Activities

1.6.3 Attitude toward the Vernacular 1.7 Facilities and Economics

1.7.1 Supply Needs 1.7.2 Medical Needs

1.7.3 Governmental Facilities in the Area 1.8 Traditional Culture

1.8.1 History

1.8.2 Attitude toward Culture 1.8.3 Contact with Other Cultures 1.9 Linguistic Work in the Language Area

1.9.1 Work Accomplished in the Past 1.9.2 Present Work

1.9.3 Materials Published in the Language

2 Methodology

2.1 Sampling on the Macro Level 2.2 Lexicostatistic Survey

2.3 Dialect Intelligibility Survey 2.4 Questionnaires

2.5 Bilingualism Testing in Jula

3 Comprehension and Lexicostatistical Data (between villages) 3.1 Reported Dialect Groupings

4 Multilingual Issues

4.1 Language Use Description 4.1.1 Children’s Language Use 4.1.2 Adult Language Use

4.2 Results of the Jula Bilingualism Test 4.3 Language Attitudes

4.4 Summary

5 Recommendations

Appendix

1 Population Statistics

2 A Word List of Dialects in the Southern Bwamu Region (section 3.3)

Bibliographical Resources 1 References

2 Other Materials about Bwamu

Bwamu Survey Report

0 Introduction and Goals of the Survey

This paper concerns the results of a sociolinguistic survey conducted by John and Carol Berthelette, Béatrice Tiendrebeogo, Dieudonné Zawa, Assounan Ouattara, and Soungalo Coulibaly. The survey was conducted between March 20 and May 8, 1995.

The survey was necessary due to a lack of data concerning the degree of

intelligibility between Bwamu speakers in the southern language area and those of the northern area. Linguists such as L. Tauxier and G. Manessey have written of the presence of different dialects in the southern Bwamu region. Manessey for example writes that the Bwaba in these areas speak the dialects of Bondoukuy, Ouakara, and Houndé-Kari (Manessey 1961:126). Nevertheless, to the present time, various

sociolinguistic questions have remained unresolved. Since a project for the

development of Bwamu has already been started in the Ouarkoye region (see map in figure 1.2.1), and since its literacy program is quickly spreading into areas that have not before been studied, it is important to determine the degree of its comprehension throughout the language area. So, in short, the four goals of the survey were:

1. to gather basic demographic and dialectal information about the Bwaba in the southern Bwamu-speaking region (especially in the area to the south and east of Pâ, very little was known);

2. to determine attitudes of those in the southern region toward both Bwamu and Jula, and to determine their level of competence in Jula;

3. to test for both the lexical similarity and the degree of comprehension between speakers in the south and the north;

4. in the event of insufficient comprehension between speakers of the southern dialect and those of the northern; in the event of very positive attitudes toward the vernacular; and in the event of an insufficient ability to communicate in Jula, the goal was to determine a possible second site for a language development project.

1 General Information

1.1 Language Name and Classification

The Ethnologue, a classification of the world’s languages published by the Summer Institute of Linguistics, classifies the Bwamu language (code “BOX”) in the following manner: “Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, North, Gur, Central, Northern, Bwamu” (Grimes 1992:168). J. H. Greenberg, while also classifying Bwamu as a Gur language, places it under the Lobi-dogon subgroup (Greenberg 1963:8). The language most closely related is Bomu (or Boré) (Naden 1989:147), found

predominantly in Mali and northwestern Burkina Faso.

Other ethnic groups often refer to them as “Bobo-wule” (or “Bobo-oule”), a name coming from Jula. In the southern Bwamu region, they are often simply called “Bobo”.

Manessy, in his 1961 paper, identified 17 dialects of Bwamu. In Mali, he

recognized 5: Koniko, Togo, Wahu, San, and Mazã’wi. In Burkina Faso, he identified 12: in the northwest area, Bo’wi, Sanaba-Bourasso, and Solenso, while to the south (and east), Massala, Dédougou, Bondoukuy, Ouakara, Sara, Houndé-Kari, Yaho, Mamou, Bagassi. (Manessy 1961:122–126). Regarding the Bwamu area south of the Bagassi dialect region, he concludes that the Bwamu spoken here is closely related to that in other dialect regions (Manessey 1961:126). He concludes that there are 4 zones of intelligibility.

Concerning the southern Bwamu dialects covered by this survey, the dialects of Bagassi, Vi, and Boni are grouped under the name . Other Bwaba refer to them as (Yé 1981:5) or . Jula speakers refer to them as “Bobo Niéniégué”, or “Bobo of the facial scarifications”, in reference to their custom of complex facial scarring (Voltz 1979:12). In the area to the east of Founzan, a small group of villages make up the dialect known as or . Scattered to the south of Founzan, stretching from east of the Mouhoun river to 100 km east of Bob-Dioulasso, are villages which speak a dialect called or 1 The speakers of the latter two dialects are intermingled. In some areas, and villages are

interspersed. In other instances, and speakers live in different parts of the same village: each learns to understand the other’s dialect, always speaking his own.

1.2 Language Location

The Bwamu-speaking territory in Burkina Faso lies within the following provinces: Kossi, Banwa, Mouhoun, Houet, Balé, Tuy, Bougouriba, and Sissili (see map in figure 1.2.1). To state it more precisely, in Burkina Faso the Bwamu region extends from the general Nouna area2 of northwestern Burkina Faso (Kossi province) south to the

general Houndé region (Houet province) and east to the area of Fara (Sissili province). It is a vast territory, in Burkina Faso covering around 18,000 km2.

The target region of this survey was the area to the south of the Houndé and Bagassi regions, itself approximately 5,000 km2, with an east-west expanse of 130 km. The area has many geographic “obstructions”: chains of hills, small rivers, and

swamps. Considering the rugged terrain and the possibility of isolation that it causes, lack of linguistic diversity would be the biggest surprise.

1Not all villages refer to themselves in this manner. Intelligibility figures and responses to

our questionnaires permit this grouping.

2North and west of the Nouna area are the Boré, or Bomu. Boré is a language closely

The Bwaba have various neighbors, including the Puguli, Dagara, Nuna, Yari (or Dagaari-Jula), Mossi, Marka, and Bobo-Madaré. Neighboring language/ethnic groups can be seen on the map in figure 1.2.1.

Figure 1.2.1

Map of Bwamu Language Area3

1.3 Population

The estimated population, according to the 1985 national census, numbers the entire ethnic group at 170,000 (INSD 1985:I,7). Assuming that the population has increased since the census was taken, the Ethnologue puts the figure at between 200,000 and 250,000 (Grimes 1992:168). Basing estimates again on the 1985 national census, population figures for the dialects covered by this study are as follows:

Table 1.3.1

Estimated Population Figures for the Southern Bwamu Dialects4

Dialect Region Population Population (with

a growth rate of 2.68% per year)5

Laa laa Bagassi / Pâ / Boni 45,812 62,923

Cwi (coo) Koti / Kabourou 17,988 24,707

Dakwi (dakoo) Kongolikan / Koumbia (Tuy Province) / Lollio/Koumbia (Balé Province)

18,574 25,512

Unidentified 4,277 5,874

1.4 Accessibility and Transport 1.4.1 Roads: Quality and Availability

Several major, well-maintained routes pass through the southern

Bwamu-speaking area. East to west runs the paved N1, the major road linking Ouagadougou, Boromo, and Bobo, as well as unpaved D29, connecting Ouahabou with the Ouarkoye region. Running north to south are unpaved N12, connecting Pâ with Dano, and R17, a route passing through Poura and Fara.

These routes are a great economic help to the area, an important agricultural region. They also allow for a degree of contact between some Bwamu dialect groups. Another result of good roads is relative ease of contact with neighboring ethnic groups, due to increased commercial activity. While some Bwamu villages are rather isolated— perhaps even cut off from motor vehicle traffic during the rainy season—this area by and large offers easy access to most villages.

In spite of the modern presence of a good road system, the hilly terrain and the large geographic area have undoubtably hindered travel in the past, contributing to the creation of the linguistic mixture that is the southern Bwamu region. Furthermore, the absence of a major route running directly from the Pâ region to the

Ouarkoye/Dédougou area (because of the Grand Bâlé River) undoubtedly plays a part

in diminishing contact—and therefore keeping alive the linguistic variation—between the dialects concerned.

1.4.2 Public Transport Systems

Since many rural peoples in Burkina Faso have limited means of personal transportation (usually a bicycle or moped), the availability of public transport is an important consideration in assessing actual and potential contact within a larger

language community. Public or commercial transport, be it by bus, bush taxi, or private merchants, is possible throughout much of the southern Bwamu region.

Two disclaimers must be included. First, notable by its absence is regular public transportation between the Boromo/Pâ region and Ouarkoye. The most reliable

transportation to the Ouarkoye/Dédougou region passes by way of Bobo-Diolasso, a situation which diminishes contact between the various dialects. Second, the villages off the main routes, even if only by a few kilometers, can become inaccessible to 4-wheel vehicles during the rainy season.

1.4.3 Trails

Numerous trails exist between Bwamu villages. In the absence of well-maintained roads, these trails allow for contact by foot, bike, and moped between villages that are not separated by too great a distance.

1.5 Religious Adherence 1.5.1 Spiritual Life

Traditional religious practices and beliefs still dominate the spiritual life of the great majority of Bwaba. We have at our disposition only the 1991 estimates of religious adherence for the entire Bwamu ethnic group; they are 85% following their traditional religion, 13% Christian, and 2% Muslim (Shady 1991). We must assume that the figures for the southern region are not extremely different.

It is noteworthy that Islam’s influence is relatively small among the Bwaba. Of course, at least some Muslim believers are found in most villages.

1.5.2 Christian Work in the Area

The Roman Catholic Church has had a long history of work among the Bwaba, recently celebrating its 50th year (Tottle 1995:18). Besides parishes established in Bomborokuy, Dédougou, and Wakara, they began work in the Boni area in 1959. The work among the Bwa in the Boni parish is currently headed by Fr. Georges Riffault. See table 1.2 in the appendix for a listing of known Roman Catholic groups. Catholic work in the Fafo area is conducted through the Dano parish.

Currently, Jim and Betty Arnold, located in Houndé, carry out church planting from Koumbia/Houndé to Founzan regions.

Two other Protestant missions are also active in the southern Bwamu area. The Assemblies of God denomination began work in Bansié (near Boni) in 1973, and have a group that numbers 150. In all, they may have over 15 churches in the southern region (FEME 1997). Five villages also have Pentacostal Church congregations. See table 1.2 in the appendix for a listing of Protestant congregations in the southern Bwamu region.

1.5.3 Language Use Parameters within Church Services

In the southern Bwamu area, most Catholic and Protestant churches work through the Bwamu language. Church services of all groups are conducted almost exclusively in Bwamu; Jula or French is sometimes used. It is probably in the Alliance Chrétienne churches in the Houndé/Koumbia region where the influence of Jula is most pronounced.

Furthermore, both Catholic and Protestant services are usually conducted in the particular dialect of the region. As we consider later the scores for inherent intelligibility between various villages and dialects, this point will carry more importance. Notable exceptions are the Catholic work in the Koti region, where residents often hear Mass conducted in the Boni dialect, and its work in Fafo.

As a final note, the use of the vernacular has been valued to such an extent that the different missions have begun translating important materials. The Catholic parish based in Boni has emphasized both translation of Scripture and literacy in the

vernacular, specifically in the Boni/Bagassi dialect. They have done much translation work themselves. Likewise, the Alliance Chrétienne and Assemblées de Dieu groups have carried out some translation and/or production of materials in the dialects of their regions, for the Alliance Chrétienne in the Ouarkoye dialect and for the Assemblées de Dieu in that of Boni. (see section 3 of the bibliographical resources for a listing of materials published in the vernacular.)

1.6 Schools/Education

1.6.1 Types, Sites, and Size of Schools

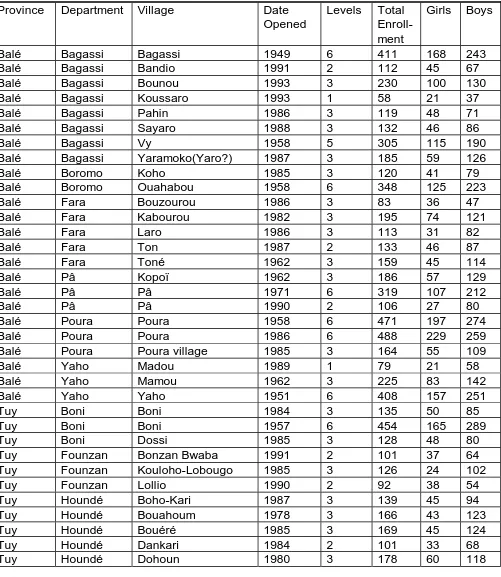

In the provinces in which the Bwaba live, primary school education has received much attention in the last two decades, as evidenced by the opening of a number of elementary schools. (See table 1.3 in the appendix for a list of primary schools in Bwamu-speaking villages in these provinces).

percentage of children who attend school is still only around 40% according to UNICEF statistics (MEBAM 1996).6 Note that the figures for the province of Houet are obviously higher than 40%. It is nevertheless safe to assume that these figures are quite high because of an undoubtedly higher scolarity rate for the city of Bobo-Dioulasso, where 39% of the population lives. The rural areas certainly have percentages that

correspond to those of the other provinces listed.

Table1.6.1

Scolarity Rate by Province

(for the 1994–1995 school year)

Province Girls’ Scolarity Rate Boys’ Scolarity Rate Total Scolarity Rate

Bougouriba 22.3% 42.2% 32.7%

Houet 47.6% 59.9% 53.9%

Mouhoun 32.9% 43.2% 38.2%

Sissili 19.7% 32.2% 26.3%

As is the case throughout the country, middle and high schools are much less common, forcing most students above primary level to travel outside of their home villages to attend (see table 1.4 in the appendix for a list of middle and high schools in the Bwamu region).

In general terms, the Bwaba seem to be highly motivated to attend school and to learn French. In fact, compared with other ethnic groups, a relatively high number seem to gain scholastic success. Nevertheless, certain factors counterbalance the desire to educate the young. The biggest single deterrent to educational access is not distance from schools, but parents’ lack of money to send their children. A second hindrance is the deeply-engrained fear among the adult Bwaba that education erodes adherence to traditional culture, again a factor which seemingly affects girls more than boys.

Another formal government educational activity is the program Centre de

Formation de Jeunes Agriculteurs. These CFJAs were developed to provide very basic education for those villages far removed from primary schools, and also are a way to educate children who don’t have the means to go to primary schools. In the province of Mouhoun, some CFJAs carry out literacy in the vernacular.7 See table 1.5 in the

appendix for listing of CFJA schools in the southern Bwamu region.

6The statistics of schooling vary between 11% for the province of Gnagna and 80% for

the province of Kadiogo.

7In the provinces of Bougouriba, Houet, and Sissili, however, literacy is carried out in

1.6.2 Literacy Activities

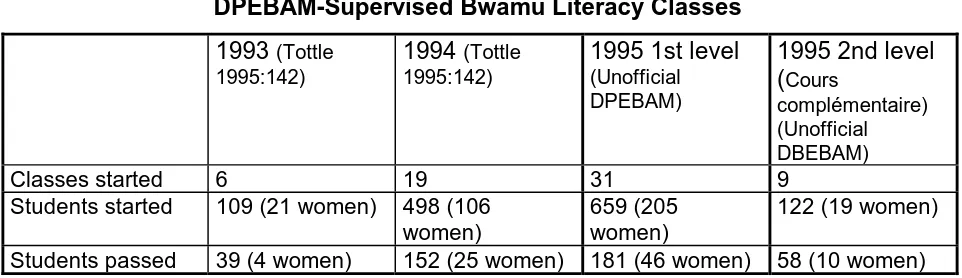

Several organizations have taken up the cause to increase literacy in Bwamu. Table 1.6.2 shows the figures for DPEBAM8-supervised Bwamu literacy.

Table 1.6.2

DPEBAM-Supervised Bwamu Literacy Classes

1993 (Tottle 1995:142)

1994 (Tottle 1995:142)

1995 1st level

(Unofficial DPEBAM)

1995 2nd level (Cours

complémentaire) (Unofficial DBEBAM)

Classes started 6 19 31 9

Students started 109 (21 women) 498 (106 women)

659 (205 women)

122 (19 women) Students passed 39 (4 women) 152 (25 women) 181 (46 women) 58 (10 women)

Certain Catholic parishes and Protestant churches are also carrying out literacy programs; a Christian primer has been produced in the Ouarkoye dialect, and is currently being revised for the Boni dialect.

1.6.3 Attitude toward the Vernacular

As was just noted, the DPEBAM has been very involved in the literacy efforts in Bwamu. As is the case with the other national languages, though, literacy, must be conducted outside of the primary and post-primary schools; French is the only

language allowed in these schools. Therefore, literacy takes place through DPEBAM and church literacy centers and CFJAs.

1.7 Facilities and Economics 1.7.1 Supply Needs

The economic situation in the general Bwamu area is similar to that of most rural Burkina Faso: almost all of the Bwaba are subsistence farmers. The southern Bwamu area is somewhat more favorable to agriculture than are, for example, areas further north. The soil is more fertile and annual rainfall is higher (Voltz 1979:13). These factors explain the higher population density than exists further north.

According to some who have worked in their region, the Bwaba have emphasized cotton planting (besides growing the staple grains), and have thus reaped some

economic benefits from this cash crop. Small markets, held every few days, are found in many villages. Often, Mossi and Jula traders sell at these markets. The Bwaba have

8Département proviciale pour l’education de base et l’alphabétisation de masse. This is

at their disposal, if not within their means, the basic goods that they need to carry on their lives.

One result of meeting people of other ethnic groups is bilingualism, and most often in Jula. It is important to note that this mixture of people groups is a strong characteristic of the market scene. Such gatherings provide the opportunity to gain at least a minimal proficiency in Jula.

1.7.2 Medical Needs

As is true for all of Burkina Faso, medical treatment is an area of great need. Throughout the Bwaba area, small dispensaries, where one can obtain very basic medical care, exist in a number of villages. However, two obstacles hinder those who need more urgent medical care: on the one hand, the distance to reach pharmacies, clinics, and hospitals, can be significant, and on the other hand, the means to pay for the treatment is often lacking. The clinics within reach of the Bwaba are in:

• Fara and Poura, for those east of the Mouhoun;

• Dano, Founzan, and Pâ, for those villages to the south of Founzan; • Bagassi, Koumbia, Houndé.

Needless to say, most Bwaba live relatively far (often at least a 2–3 hour journey) from clinics, the result being that by the time the sick arrive for treatment, it can be too late.

1.7.3 Governmental Facilities in the Area

The various departmental seats/prefectures often fall within the Bwamu-speaking area; nevertheless, this fact is less true in the area to the south of Pâ. In these offices, French and Jula are the languages used. Police checkpoints are not uncommon; French is the language of use here. Several police barracks are found within the Bwamu-speaking area—only in the area to the south of Pâ would one have to travel outside the area to find a policeman. Nevertheless, proficiency in either French or Jula is desirable.

1.8 Traditional Culture 1.8.1 History

According to Voltz, it was the Bwaba who were the first ethnic group to settle in their region; it is quite likely that they have inhabited it for more than 1,000 years. He writes so well that until the 18th century, the southern Bwaba apparently enjoyed little conflict. This period of calm resulted in the Bwaba being able to develop cultural and societal patterns that were distinct from their neighbors’. In the last two centuries, however, both conflict and the facets of modernization have caused great changes in their society (Voltz 1979:13).

1.8.2 Attitude toward Culture

group as a whole. To be sure, within the village communities there is a

firmly-established structure. For example, decisions are made by a village’s council of elders; in the Bwaba cultural system there are also other established religious and social positions (Voltz 1979:16). Nevertheless, on the macro level—between villages—the villages are very independent, and display a great desire to remain so (Voltz 1979:16). This independence also taints the Bwaba’s relationship toward the Burkina Faso governmental structures (Voltz 1979:13).

Related to the matter of individualism within the group, it must be stated that the Bwaba are also somewhat independent with regard to neighbors. While nowadays they show little or no open antagonism to those of other ethnic groups, they state clearly that their culture and way of living are better, and that they wish to keep their own cultural practices. And in general, the Bwaba are happy with village life. According to those responding to our questionnaires, most prefer the life of the village to life away and in the big cities. As is the case of many Burkina ethnic groups, many young, especially men, spend a bit of time “seeking fortune” in Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, and Ghana. While it is impossible to know how many actually return to their home village, it would seem that a fairly high percentage do return after their money-making stint. A result of these stays is usually greater proficiency in Jula.

A third characteristic is the overall good work ethic among the Bwaba, coupled with the afore-mentioned desire to learn.

A final comment concerns the groups’ power-brokers. As mentioned earlier, decisions are made by a council of elders. It should be stated explicitly that in Bwaba society, the oldest men in a particular village have the greatest influence (Voltz 1979: 20).

1.8.3 Contact with Other Cultures

In section 1.2, we noted factors that encouraged linguistic diversity in the past; conflicts with neighboring ethnic groups have contributed as well to the jumbled

dialectal situation. Relations with the Mossi in particular have not always been good; in the past, there have been confrontations. These struggles are yet another factor that has led to the mixing of dialects in the southern language area: in the past, Bwaba were either displaced or felt pressured to relocate.

Patterns of contact can be seen through a study of the masks used in the

traditional religion. In the past, it appears that the southeastern area, basically that of the Twi, were somewhat influenced culturally by the Nuna, their neighbors to the east. While, the Dakwi, who dominate the western regions, have some Nuna influence, it is less apparent. Instead, one sees more definite ties to the Bobo-Madaré, who border the Dakwi to the west (Voltz 1979:38).

Vigué; to the west, with Bobo-Madaré (Bobo-Fing) and Jula; and to the north, with Mossi, Marka, and Winyé. It is especially in the area to the west of the Mouhoun River that contact translates into greater proficiency in Jula.

1.9 Linguistic Work in the Language Area 1.9.1 Work Accomplished in the Past

As stated above, Manessy carried out an extensive survey some 30 years ago, helping to delineate the Bwamu dialect boundaries. He has also written other articles on the language. In the late 1970s, a team from the Société Internationale de

Linguistique began work in the Boni area, publishing a paper on the phonology of the Boni/Bagassi dialect.

Dr. Vinou Yé, a professor of linguistics at the University of Ouagadougou, has been a great resource and help in the studies of the Bwamu language. He has both published papers of his own and directed the research of others in the formal study of different Bwamu dialects. C. Botoni and J. K. Zongo are among those who have written on the language, focusing on the Karaba and Dédougou dialects respectively.

See section 2 of the appendix for a listing of linguistic, historical, and anthropological works about the Bwaba.

1.9.2 Present Work

Based on the data from a 1986 survey conducted by Bob and Anne Jackson, the SIL team of Sharyn Thomson and Ruth Allen began work in the Ouarkoye dialect in 1991, joined by Terttu Viinikkala in 1993. To this point, they have worked alongside the Bwamu Language Commission in developing an orthography and are currently

preparing a paper on this dialect’s phonology. Certain SIL researchers have worked with the team for short periods, including Stephanie Douglas, Mary Grant, and Gillian Hibbert, concentrating on grammatical analysis. Leanne Nutting joined the team in 1995.

1.9.3 Materials Published in the Language

The DPEBAM and SIL (mostly in the person of Terttu Viinikkala) are currently teaming up to carry out literacy campaigns in the vernacular in various Bwaba villages. This partnership has helped in the production of a primer (currently being revised), a songbook, 2 story books, 2 books on health, one on farming, helps for literacy

teachers, and calendars. The Association Nationale pour la Traduction de la Bible et de l’Alphabétisation (ANTBA.) produced a Christian-themed primer. See section 3 in the appendix for a list of materials published in Bwamu.

2 Methodology

2.1 Sampling on the Macro Level

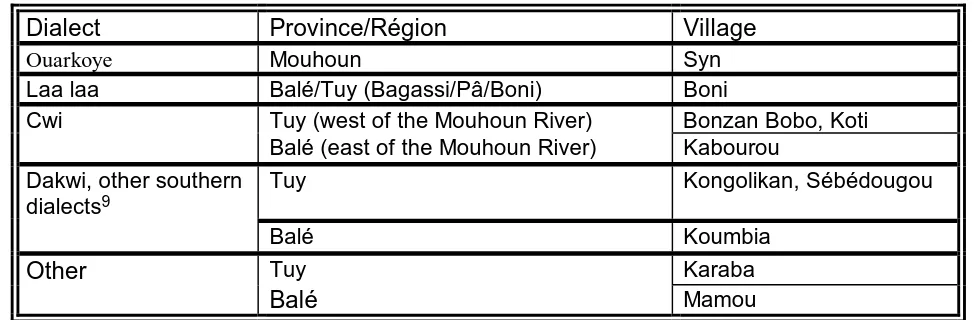

similarity and the degree of inherent intelligibility between the various dialect regions, we conducted research in the villages as shown in table 2.1.1.

Table 2.1.1

Village visited based on reported dialect boundaries

Dialect Province/Région Village

Ouarkoye Mouhoun Syn

Laa laa Balé/Tuy (Bagassi/Pâ/Boni) Boni

Cwi Tuy (west of the Mouhoun River) Bonzan Bobo, Koti

Balé (east of the Mouhoun River) Kabourou Dakwi, other southern

dialects9

Tuy Kongolikan, Sébédougou

Balé Koumbia

Other Tuy Karaba

Balé Mamou

2.2 Lexicostatistic Survey

To determine the degree of lexicostatistic similarity, we elicited a 230 item word list, with various parts of speech included in it. As part of our second pass through each village, we checked discrepancies with data from contiguous dialects in order to avoid mistaken data and therefore achieve purer results. (See section 2 in the appendix for a complete list of the glosses and data.)

2.3 Dialect Intelligibility Survey

In order to measure the degree of inherent intelligibility between speakers of the various dialects, we followed the methodology developed by E. Casad (1974),

commonly referred to as the Recorded Text Test (RTT). The various steps are as follows:

1. A text is elicited from a native speaker of Village A, a text as free as possible from objectionable subject matter and words borrowed from another language. 2. A group of 12–15 questions are developed based on the text. These questions

are recorded in the dialect of Village A and inserted into the text. From six to ten native speakers of the dialect of Village A listen to the text and respond to the questions, in order that any badly composed or misleading questions can be isolated and removed. The 10 best questions, to which almost all native speakers have responded correctly, are chosen for the final form of the test.

3. The refined text/test of Village A is played in Village B, having recorded Village A’s questions in the dialect of Village B and inserted them in the text. At least 10 speakers in Village B listen to the text, responding to the questions. Their cumulative scores on the recorded test are taken as the percentage of their intelligibility with the dialect of Village A.

A note about sampling: in the testing process in Village B, it is very important to be aware of and guard against the influence of factors that may skew the results, and in particular, factors which may allow respondents to achieve higher scores. For example, it is important to choose candidates with very little or no previous contact with speakers of Village A. Such exposure may allow them to score higher on this test, one designed to measure inherent (natural) intelligibility. In table 3.2.1, it is the standard deviation column which signals high contact, and therefore learned intelligibility. A high (above 1.6) standard deviation, a result of a wide range of test scores, suggests that some testees have “learned” to understand the speech tested. Learned intelligibility is generally not consistent within a population.

Conversely, it is just as important to find candidates who can master the

question/answer technique of the Casad methodology. It is sometimes not an easy feat among those who have not gone to school.

2.4 Questionnaires

We questioned two to four men from each village concerning both general demographic and general sociolinguistic matters. The subject matter covered by the questionnaires ranged from the ethnic composition and facilities in the area to

perceived dialect differences, bilingualism, and language use. The men were chosen by the village’s government representative, and sometimes included the representative himself. Due to the surveyors’ not knowing the trade language and a desire to better monitor the questioning process, the questionnaires were carried out in French. We also interviewed available school teachers and religious leaders using prepared questionnaires. Results of the sociolinguistic questionnaires form the basis of much of our discussion below on dialect attitudes (3.1) and multilingualism (4).

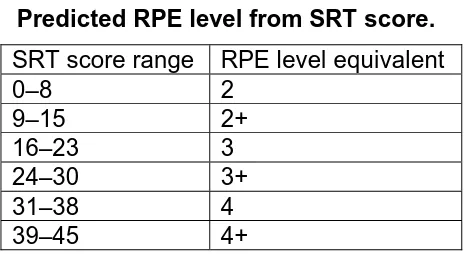

2.5 Bilingualism Testing in Jula10

The Sentence Repetition Test (SRT) for the Jula language was developed by following the procedures of Radloff (1991). An SRT is comprised of 15 sentences, arranged in increasing order of difficulty. For each sentence answered correctly, 3 points are earned, with 45 being a maximum score. For each mistake, a point is subtracted from 3. The SRT, used to assess proficiency in Jula, was calibrated to a Reported Proficiency Evaluation (RPE).11 The sample used to calibrate the SRT with the RPE consisted of 83 people who were both native and second language Jula

speakers. They were volunteers found in the city of Ouagadougou.

The regression equation for predicting RPE means from SRT means was:

RPE = 1.94 + 0.0665 SRT

This calibration allows for a prediction of RPE levels based on the SRT scores, according to table 2.5.1.

Table 2.5.1

Predicted RPE level from SRT score.

SRT score range RPE level equivalent

0–8 2

9–15 2+

16–23 3

24–30 3+

31–38 4

39–45 4+

A further comparison was done between the SRT scores and an oral proficiency exam using SIL’ s Second Language Oral Proficiency Evaluation (SLOPE) (SIL 1987). A subset of 25 of the most proficient speakers of the original sample was evaluated with this oral interview technique. It was found in this study that those scoring at or above 25 on the SRT could be reliably classed in SLOPE level 4; those scoring below 25 were below SLOPE level 4. This particular level represents the ability to “use the language fluently and accurately on all levels normally pertinent to needs” (SIL 1987:34). The discrepancy between RPE and SLOPE evaluations in relation to SRT scores, along with broader issues concerning the interpretation of the SRT, are discussed at length in Hatfield, ms.

In addition to the calibration effort, the completed SRT was given to a sample of reported native speakers of Jula in two villages of southwest Burkina, Péni and Sindou to provide a means of comparison between L1 and L2 speakers of Jula in Burkina. The collective mean SRT score from samples in both villages was 30.5, lower than

expected but still corresponding to a high level of Jula competence. This gives us a baseline of comparison between native and non-native speakers of Jula, and allows us to say that scores of 30 and above indicate a competence level similar to that of native speakers, as measured by this test. A full report on the development of the Jula SRT in Burkina Faso can be found in Berthelette et al. 1995.

To understand the interacting influences of sex, age, and geographical location of villages on Jula proficiency, a factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistical design was used on the SRT scores. This design was based on SRT data collected from both females and males whose ages were from 12 and up, and who lived in 10 villages. The specific factors examined were age with three levels: 12–25, 26–45, and 46+ years; villages with 10 levels; and sex with two levels. Interacting effects among these factors were examined. The specific ANOVA selected for the analysis was the General Linear Model (GLM) because the requirement of a balanced design was not a precondition for its use. A balanced ANOVA design requires equal numbers of subjects at all factor levels. Another unique feature of the GLM is that it considers the correlation

coefficients among age, sex, and villages. These relationships were examined by regression analysis which involves correlational analyses. The GLM makes

adjustments in the factor level means and standard deviations which are predicted from the correlated data.

Differences between factor level means which occurred by chance 5% or less were considered statistically significant. In probability terms, if mean differences in SRT scores occurred by chance five times or less out of 100 times between levels of a factor they would be considered statistically significant. In that case, the factor level with the largest mean would be considered more bilingual than the other level. If statistical significance was found among three or more levels, the Tukey test was used to determine which means were significantly different from each other.

In general, language groups having the SRT means below 16 (level 3 on RPE scale) were prioritized for minority language development while language groups with significantly higher SRT means had a lower priority. Of course, attitudinal factors were also considered when priorities were determined (Bergman 1989:9.5.2).12

3 Comprehension and Lexicostatistical Data (between villages)

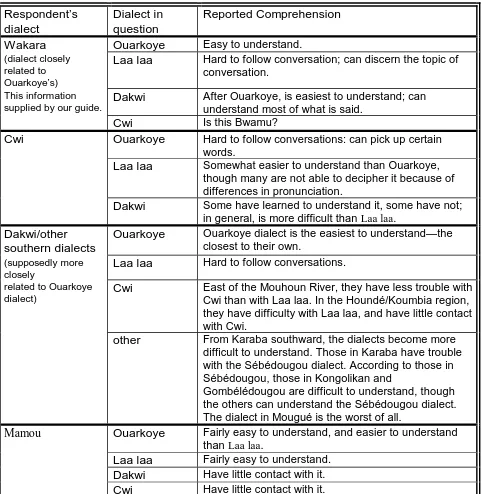

3.1 Reported Dialect Groupings

It is always interesting—and challenging—to try to pinpoint how villagers perceive their own ability to understand other languages or dialects. Just as challenging is the attempt in table 3.1.1 to summarize the Bwaba opinions.

12In 1989, the Summer Institute of Linguistics’ Area Directors and Vice Presidents

established the language assessment criteria for the organization. This work is a set of

Table 3.1.1

Reported self-evaluation of intelligibility between Bwamu dialects

Respondent’s dialect

Dialect in question

Reported Comprehension

Wakara Ouarkoye Easy to understand.

(dialect closely related to Ouarkoye’s)

Laa laa Hard to follow conversation; can discern the topic of conversation.

This information supplied by our guide.

Dakwi After Ouarkoye, is easiest to understand; can understand most of what is said.

Cwi Is this Bwamu?

Cwi Ouarkoye Hard to follow conversations: can pick up certain words.

Laa laa Somewhat easier to understand than Ouarkoye, though many are not able to decipher it because of differences in pronunciation.

Dakwi Some have learned to understand it, some have not; in general, is more difficult than Laa laa.

Dakwi/other southern dialects

Ouarkoye Ouarkoye dialect is the easiest to understand—the closest to their own.

(supposedly more closely

Laa laa Hard to follow conversations.

related to Ouarkoye dialect)

Cwi East of the Mouhoun River, they have less trouble with Cwi than with Laa laa. In the Houndé/Koumbia region, they have difficulty with Laa laa, and have little contact with Cwi.

other From Karaba southward, the dialects become more difficult to understand. Those in Karaba have trouble with the Sébédougou dialect. According to those in Sébédougou, those in Kongolikan and

Gombélédougou are difficult to understand, though the others can understand the Sébédougou dialect. The dialect in Mougué is the worst of all.

Mamou Ouarkoye Fairly easy to understand, and easier to understand than Laa laa.

Laa laa Fairly easy to understand. Dakwi Have little contact with it. Cwi Have little contact with it.

In summary, the Bwaba from the different dialect regions have definite opinions regarding differences in speech. As we shall see in sections 3.2 and 3.3, these opinions generally fall in line with results from the Recorded Text Test.

example lies in villages such as Lollio, Kovio, Bonzan Bobo, and Founzan. Dakwi and Cwi speakers live side by side; according to residents, however, speakers of the respective dialects are not adapting their dialects. They learn to understand the other, but respond in their own. According to those we talked to among the three dialects, Laa laaand Cwispeakers express the strongest attachments to their speech.Underlining a trend in the table 3.1.1, theCwi dialect is generally regarded by others as difficult and strange.

Concerning Cwi, those who answered our questions left the impression that they were as proud or prouder of their dialect affiliation than of their ties with the larger Bwamu community.

3.2 Results of the Recorded Text Tests

While it is true that some learning of other dialects takes place through contact, few Bwaba seem to have the opportunity to do this. Thus, we are faced with the need for verifiable data to see if the Ouarkoye materials should be adapted, doing so in order to provide the southern dialects with the best possible opportunity to learn to read and write in their own language. Linguists who have worked with the Recorded Text Test have debated the threshold of comprehension speakers of one dialect must attain if they are to be reasonably expected to profit from literacy materials and a translation of the Scriptures. An accepted minimum threshold for the Summer Institute of Linguistics is 75% (Bergman 1990:9.5.2).

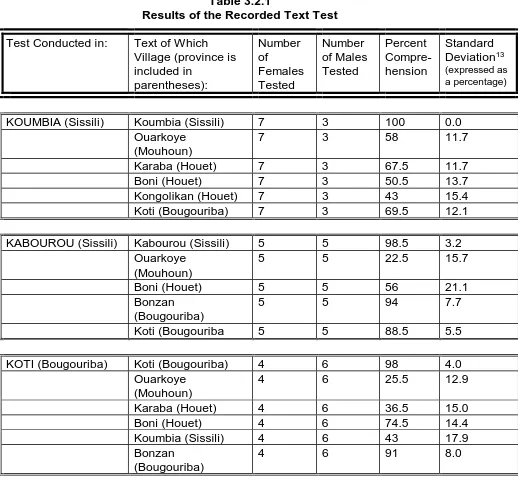

Table 3.2.1

Results of the Recorded Text Test

Test Conducted in: Text of Which Village (province is included in

KOUMBIA (Sissili) Koumbia (Sissili) 7 3 100 0.0

Ouarkoye (Mouhoun)

7 3 58 11.7

Karaba (Houet) 7 3 67.5 11.7

Boni (Houet) 7 3 50.5 13.7

Kongolikan (Houet) 7 3 43 15.4

Koti (Bougouriba) 7 3 69.5 12.1

KABOUROU (Sissili) Kabourou (Sissili) 5 5 98.5 3.2 Ouarkoye

Koti (Bougouriba 5 5 88.5 5.5

KOTI (Bougouriba) Koti (Bougouriba) 4 6 98 4.0

Ouarkoye (Mouhoun)

4 6 25.5 12.9

Karaba (Houet) 4 6 36.5 15.0

Boni (Houet) 4 6 74.5 14.4

Koumbia (Sissili) 4 6 43 17.9

Bonzan (Bougouriba)

4 6 91 8.0

13As stated above, it is the standard deviation column which signals high contact, and

Test Conducted in: Text of Which Village (province is included in

BONI (Houet) Boni (Houet) 3 7 96.5 5.5

Ouarkoye (Mouhoun)

3 7 28 15.5

Karaba (Houet) 3 7 53 17.5

Koumbia (Sissili) 3 7 44 10.2

Bonzan (Bougouriba)

3 7 46 12.8

Koti (Bougouriba) 3 7 15.5 11.9

KARABA (Houet) Karaba (Houet) 6 4 99 3.0

Ouarkoye

Koumbia (Sissili) 6 4 54.5 20.8

Koti (Bougouriba) 6 4 17 12.5

MAMOU (Mouhoun) Mamou (Mouhoun) 8 3 95.45 7.8

Ouarkoye (Mouhoun)

8 3 76.36 24.3

Boni (Houet) 8 3 79.55 8.4

Koumbia (Sissili) 8 3 43.64 18.7

Koti (Bougouriba) 8 3 17.73 14.4

SEBEDOUGOU (Houet)

Sébédougou (Houet) 9 1 98.5 2.3

Ouarkoye (Mouhoun)

9 1 82.5 11.9

Karaba (Houet) 9 1 59 10.4

Boni (Houet) 9 1 51 11.4

Koumbia (Sissili) 9 1 94 6.6

Test Conducted in: Text of Which Village (province is included in

Kongolikan (Houet) 6 5 97.27 6.2

Ouarkoye (Mouhoun)

6 5 60.45 9.9

Karaba (Houet) 6 5 50.91 13.1

Boni (Houet) 6 5 33.64 9.6

Koumbia (Sissili) 6 5 86.36 14.2

Koti (Bougouriba) 6 5 10 11.3

How do we interpret the above figures? I will underline again two of the main goals of the survey:

♦ to gather basic information about the Bwaba in the southern Bwamu-speaking region, about whom very little was known; and

♦ to test for both the lexical similarity and the degree of inherent intelligibility of Ouarkoye dialect by Bwamu speakers in the south.

Regarding the second goal of the survey, it is very clear looking at table 3.2.1, that subjects in various villages had difficulty with the Ouarkoye text. Of the villages tested, only in Sébédougou was the inherent intelligibility above 80%, and only in Mamou and Karaba was the intelligibility above 70%. The conclusion, therefore, is that Ouarkoye materials need to be adapted for the southern region: using these materials without dialect adaptation for literacy and language development may have the

negative consequence of discouragement in learning to read in Bwamu.

Let us consider at this point a third goal of the survey:

♦ in the event of insufficient comprehension between speakers of the south and those of the north, to determine a possible second site for language

development work.

How do the survey results speak to this goal? Considering again the data from, table 3.2.1, we note that:

the case of both the Cwiand Dakwidialects, the level of inherent intelligibility is not uniform throughout the dialect regions. On one hand, the percentages for villages of both dialects located east of the Mouhoun River—Kabourou (Cwi) and Koumbia (Dakwi)—lie between 50% and 60%. Likewise, percentages for Dakwi-related villages in the west—namely Kongolikan and Sébédougou—lie in that same 50%– 60% range.14 Therefore, the conclusion we draw is that the Laa laa,

Bagassi/Boni/Pâ dialect needs its own literacy materials, but is itself not suitable for either Cwi or Dakwi dialects.

2. Regarding the Dakwi (Koumbia) text, neither Laa laanor Cwispeakers sufficiently understood it—the percentages lie between 40% and 50%. We expect that Cwi speakers have learned the Dakwi dialect to varying degrees—some may even understand it fluently. Nevertheless, this kind of learned intelligibility results mostly from interdialectal contact and is not uniform among a village’s inhabitants.

3. Regarding the Cwi (Koti and Bonzan) texts, it is again the case that they are not sufficiently understood by either speakers of the Laa laaor Dakwi dialects. The inhabitants of Koumbia (Dakwi) have the highest intelligibility, at 69.5%; an offsetting factor is that Koumbia lies 2 km from Toné, a Cwivillage. Toné is the village which Koumbia residents must cross to reach the main road, the village in which Koumbia children attend school, and the village in which the closest large market is held. This is probably another case of learned intelligibility, albeit that the standard deviation is not excessively high.

4. The speakers of Mamou may find materials in the Laa laadialect to be more suitable.15

3.3 Percentage Chart of Apparent Cognates

Table 3.3.1 is the cognate percentage chart, an analysis of apparent cognates based on our word list data. While the percentages do not strongly reinforce the scores from the RTT, neither do they undermine those results. To put it simply, when

comparing one Bwamu dialect to another, the percentage of lexical similarity is not high. The word lists were verified in order to best assure that differences did not simply involve the use of synonyms.

14We group Sébédougou and Kongolikan in the Dakwi dialect on the basis of the results

of the Recorded Text Test. In both cases, the percentage of inherent intelligibility lies well above the 80% threshold, a surprising fact considering the geographical distance separating the two villages. It is also surprising to find that Koumbia residents had great difficulty with the Kongolikan text. We note, however, that inhabitants of neither Sébédougou nor Kongolikan profess to being a part of a Dakwi subgroup of Bwamu.

15It is on the basis of the Recorded Text Test results that we include the population

Table 3.3.1

Overall Lexical Similarity Percentages for the 1995 Bwamu Survey

Ouarkoye (Houet)

68 Karaba (Houet)

52 52 Mamou (Houet)

56 62 58 Boni (Houet)

57 58 47 53 Sébédougou (Houet)

56 56 43 54 69 Koumbia (Sissili)

53 51 43 48 66 67 Kongolikan (Houet)

41 42 40 45 47 53 44 Koti (Bougouriba)

40 39 38 43 45 52 43 94 Kabourou (Sissili)

Table 3.3.2 shows more clearly the groupings of the highest lexical similarity percentages. These figures coincide with both personal evaluations (section 3.1) and Recorded Text Test scores (section 3.2). Note, however, that these figures are lower than expected. It is our experience that word list percentages within a dialect group generally lie at 80% or higher.

Table 3.3.2

Lexical Similarity Percentages Grouped According to Dialects

Ouarkoye Dakwi Cwi

Ouarkoye (Houet) 68 Karaba (Houet)

Sébédougou (Houet) 69 Koumbia (Sissili) 66 67 Kongolikan (Houet)

Koti (Bougouriba) 94 Kabourou (Sissili)

For complete word lists for the villages in table 3.3.2, see section 2 in the appendix.

3.4 Areas for Further Study

Several questions remain after the survey. For example, we were not able to visit two villages: Mougué and Naouya. In response to questions, villagers from Kabourou state that the inhabitants of Naouya speak a dialect similar to that of Bagassi.

A second matter has to do with the lower than expected percentages of lexical similarity. What will more in-depth study in the dialects show?

Furthermore, it should be noted that in five to ten years, the sociolinguistic

situation should again be evaluated. Attitudes and dialect use can change, sometimes quite rapidly.

4 Multilingual Issues

4.1 Language Use Description 4.1.1 Children’s Language Use

The language of all Bwaba homes, according to the Bwaba who answered our questions, is Bwamu. Of course, most villages have at least one sector of inhabitants of another ethnic group. Therefore, many Bwaba children learn to speak a second

language, be it Nuni, Jula, or Mooré (in villages east of the Mouhoun River) or Jula (elsewhere), to a functional level, because of school, market, and normal village

contact. A key question included in our questionnaires is whether many village children learn to speak a second language before age 7. Only in Karaba did the respondent answer “yes”, thus signalling little need and motivation to learn a second language at an early age.

4.1.2 Adult Language Use

Between adult Bwaba, there is no doubt that the preferred language is Bwamu. As in the case of the children, many Bwaba learn Nuni, Jula, or Mooré (in villages east of the Mouhoun River) or simply Jula (elsewhere) in order to do business in the local markets. A certain percentage of the population travel to Côte d’Ivoire to earn money, where Jula is the trade language; we should assume that their Jula improves as a result. It must be stressed; however, that these languages are used mainly in the domain of the marketplace and in communicating with non-Bwaba.

4.2 Results of the Jula Bilingualism Test16

Table 4.2.1 presents the results of the Jula Sentence Repetition Test. The test was administered in 10 villages spanning the southern Bwamu region. In choosing the sites, we divided the southern area into four subregions, and as well we tried to

conduct tests in at least one village with much ethnic contact and one village with supposedly less ethnic contact for each of these different subregions. For example, in the area east of the Mouhoun River, Kabourou was the choice for a village with little interethnic contact, as it has few non-Bwaba, while Payalo, only 1/3 Bwamu, represents those villages with much interethnic contact. Table 4.2.1 summarizes the choice of villages.

Table 4.2.1

Choice of Test Sites for Jula Sentence Repetition Test

Region Villages East of the

Mouhoun River

Kabourou Payalo Payalo is 1/3 Bwamu, 2/3 Nuni, while Kabourou has few non-Bwaba.

Koti has much contact with Puguli. Pâ, of course, has become a travel stop on the main highway, and has an increasing number of non-Bwaba. Founzan is on a less-frequented road than Pâ, but has a mix of ethnic groups.

65% much 35% little

Bagassi area Badio Mamou Mamou is on the main road between Bagassi and Yaho and quite near some Marka villages; Badio is somewhat removed.

We assumed that

Sébédougou would represent villages with little interethnic contact; on testing, we discovered that there are many Mossis and Peuls in the area. Koumbia is on the main highway to Bobo-Dioulasso.

75% much 25% little

sense of the word; that is, we do not presume that every villager has the same opportunity to be tested.17

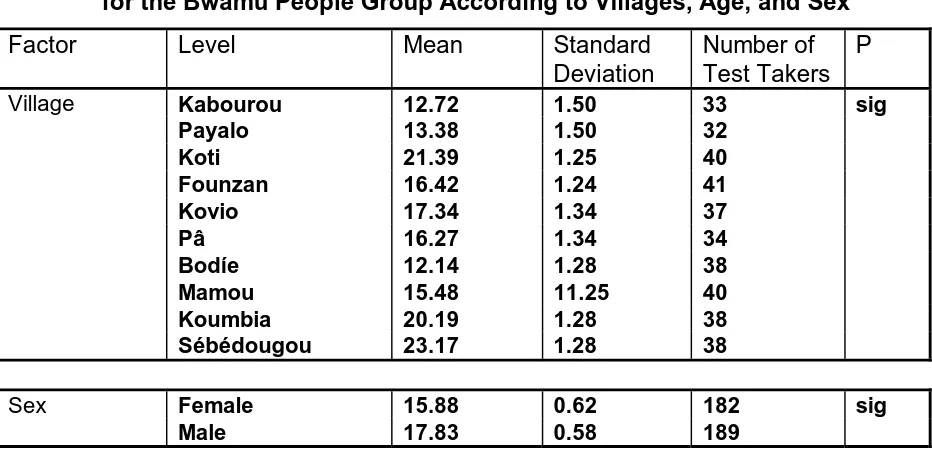

A comparison was made of the SRT means of the Cwi, Laa laa, and Dakwi dialects for the purpose of determining and comparing their proficiency in Jula. The villages representing the Cwi dialect (Kabourou, Payalo, Koti, Founzan, and Kovio) had a combined SRT mean of 13.03; the Laa laa dialect villages of Pâ, Bodíe, and Mamou had a combined SRT mean of 16.44; and the Dakwi dialect villages of Koumbia and Sébédougou had a combined mean of 21.70. The SRT means and standard deviations of the dialects and each of the villages representing the dialects are presented in table 4.2.2. The analysis of variance found a highly significant difference among the three dialect groups (p < 0.001 ), but no significant differences were found for main effects of sex or age, nor were any interactions significant.

The results of these comparisons provided a basis for language development priorities. The level of proficiency in Jula for the Dakwi dialect was relatively high at 21.70 which predicted an RPE mean level 3. When compared to the low proficiency levels of 13.03 and 16.44 for the other two dialects, priority in language development was assigned to speakers of the Cwi and Laa laa dialects.

Table 4.2.2

Means and Standard Deviations of SRT Scores

for the Bwamu People Group According to Villages, Age, and Sex

Factor Level Mean Standard

Deviation

Number of Test Takers

P

Village Kabourou 12.72 1.50 33 sig

Payalo 13.38 1.50 32

Koti 21.39 1.25 40

Founzan 16.42 1.24 41

Kovio 17.34 1.34 37

Pâ 16.27 1.34 34

Bodíe 12.14 1.28 38

Mamou 15.48 11.25 40

Koumbia 20.19 1.28 38

Sébédougou 23.17 1.28 38

Sex Female 15.88 0.62 182 sig

Male 17.83 0.58 189

17Two factors make scientifically random sampling extremely difficult to achieve. Firstly,

Factor Level Mean Standard Deviation

Number of Test Takers

P

Age 12–25 18.48 0.66 141 sig

26–45 18.01 0.66 139

46+ 14.06 0.85 91

Village x Sex Kab x F 9.57 2.27 15 sig

Kab x M 15.87 1.85 18

Pay x F 13.56 2.38 13

Pay x M 13.21 1.79 19

Koti x F 20.51 1.76 20

Koti x M 22.26 1.76 20

Foun x F 15.48 1.76 20

Foun x M 17.36 1.72 21

Kovio x F 15.81 1.96 17

Kovio x M 18.87 1.76 20

Pâ x F 14.64 1.84 18

Pâ x M 17.90 1.95 16

Bod x F 14.89 1.80 19

Bod x M 9.40 1.80 19

Mam x F 16.01 1.72 21

Mam x M 14.95 1.80 19

Koum x F 17.17 1.74 20

Koum x M 23.21 1.87 18

Sébé x F 21.12 1.80 19

Factor Level Mean Standard Deviation

Number of Test Takers

P

Village x Age Kab x 12–25 12.29 2.08 14 ns

Kab x 26–45 13.11 2.16 13

Kab x 46+ 12.77 3.36 6

Pay x 12–25 13.74 2.16 13

Pay x 26–45 14.24 2.26 12

Pay x 46+ 12.16 3.18 7

Koti x 12–25 24.89 2.01 15

Koti x 26–45 25.07 2.01 15

Koti x 46+ 14.20 2.46 10

Foun x 12–25 17.56 1.95 16

Foun x 26–45 19.39 2.01 15

Foun x 46+ 12.30 2.46 10

Kovio x 12–25 18.14 2.08 14 Kovio x 26–45 17.88 2.01 15

Kovio x 46+ 16.00 2.78 8

Pâ x 12–25 15.41 2,35 11

Pâ x 26–45 19.60 2.16 13

Pâ x 46+ 13.80 2.46 10

Bod x 12–25 16.07 2.08 14

Bod x 26–45 11.36 2.08 14

Bod x 46+ 9.00 2.46 10

Mam x 12–25 20.42 2.01 15

Mam x 26–45 17.51 2.01 15

Mam x 46+ 8.50 2.46 10

Koum x 12–25 20.71 2.08 14

Koum x 26–45 21.36 2.08 14

Koum x 46+ 18.50 2.48 10

Sébé x 12–25 25.53 2.01 15

Sébé x 26–45 20.59 2.16 13

Sébé x 46+ 23.00 2.46 10

Sex x Age F x 12–25 15.68 0.92 72 sig

F x 26–45 18.83 0.94 69

F x 46+ 13.13 1.31 41

M x 12–25 21.27 0.94 69

M x 26–45 17.21 0.93 70

4.3 Language Attitudes

According to the answers to our questionnaires, French is seen as a prestige language; in most cases, mastering it is one prerequisite to getting a good job. Nevertheless, fairly few do master it, and once out of school and settled in normal village life, most gradually lose some of their ability through disuse.

Jula, of course, is the language that most Bwaba use as their second language. In many villages, the Bwaba see learning Jula as important; it is the means to

communicate with those of other ethnic groups. Their attitudes, however, are based on the necessities of their situations; they are attracted to it for its usefulness. It is clear that the real language of the heart is Bwamu. The Bwaba attitudes are most clearly revealed when they answer questions concerning the language choice of their religious practices. When it comes to conducting the important cultural practices, the Bwaba state that using Jula is out of the question. It is only at Kongolikan, less than 100 km from Bobo, that Bwaba can see a day when their descendants will no longer speak their mother tongue.

4.4 Summary

Though the Bwaba subjects as a whole showed a moderate competence in Jula, it seems clear they reserve the use of Jula for communication with outsiders. By contrast, they hold strongly positive attitudes toward the different varieties of Bwamu. Speakers of the southern varieties are strongly attached to their mother tongue, which suggests that the best results of literacy and language development work will almost certainly come through the local variety. It would be a shame to not take advantage of their desire to read and write in it.

A final reminder, however: in certain areas of the southern Bwamu region, bilingualism in Jula is a topic that will require further attention in the future. In the Founzan and southwestern Bwamu areas, where there exists the greatest amounts of interethnic contact, one must continue to look for signs of shifting attitudes.

5 Recommendations

The Ouarkoye dialect of Bwamu does not appear to be sufficiently intelligible among Bwaba of the southern language area for use in literacy training. It is my

recommendation that two projects be carried out in the southern Bwamu language area and that both involve the use of CARLA (Computer Assisted Related Language

Adaptation—see Mann and Weber, 1990).

The first definite need is in the Bagassi/Pâ/Boni dialect region. The choice as to where to allocate is not clear; there are compelling reasons for any of a number of sites. It would be up to the allocated team to meet in consultation with influential dialect speakers—Dr. Vinou Yé, Catholic and Protestant church leaders, and traditional

The second definite need is in the Cwidialect area. From the study carried out to this point, there is sufficient reason for arguing that this dialect be developed: poor inherent intelligibility with any dialect to be developed, strong attitudes toward the dialect, and strong church desire to see the New Testament translated into the

dialect.This team should nevertheless have as a high priority, further study of both the Cwiand Dakwi dialect situations, evaluating in more depth the interrelationship

between the two dialects and the sociolinguistic situation as a whole.

In making this assignment, it should be made very clear to the team that this assignment is a definite need under provisional status: that is to say, after 2 years of study, the situation should be reevaluated by the Sociolinguistic Coordinator, the Director, the Language Programs Manager, and the Survey Team Leader. Possible outcomes include:

• the team providing clear evidence that the Cwiproject should continue, whereupon the provisional status is removed;

• the team demonstrating that the dialect situation is such that the Cwidialect does not need to be developed;

• the team providing further sociolinguistic evidence regarding the need (or lack thereof) for the Dakwi dialect.

In conversations with the Sharyn Thomson and Ruth Allen, they have stated that they are planning to carry on an adaptation of the Ouarkoye materials for a southern translation project. Any assignment in the southern area should be made in

consultation with them.

Appendix

1 Population Statistics

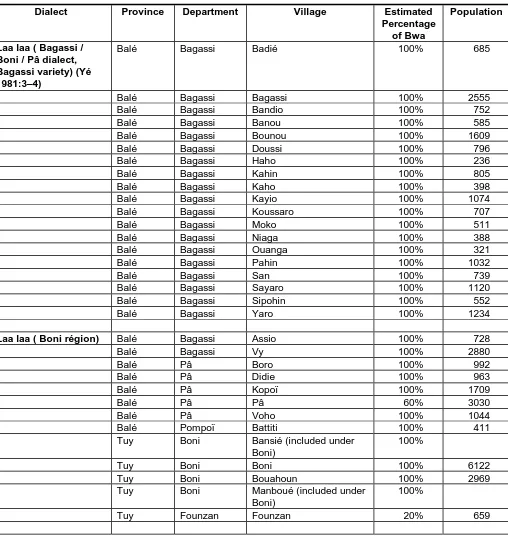

Table 1.1

Breakdown of Southern Bwamu Dialects

Dialect Province Department Village Estimated

Percentage of Bwa

Population

Laa laa ( Bagassi / Boni / Pâ dialect, Bagassi variety) (Yé 1981:3–4)

Balé Bagassi Badié 100% 685

Balé Bagassi Bagassi 100% 2555 Balé Bagassi Bandio 100% 752 Balé Bagassi Banou 100% 585 Balé Bagassi Bounou 100% 1609 Balé Bagassi Doussi 100% 796 Balé Bagassi Haho 100% 236 Balé Bagassi Kahin 100% 805 Balé Bagassi Kaho 100% 398 Balé Bagassi Kayio 100% 1074 Balé Bagassi Koussaro 100% 707 Balé Bagassi Moko 100% 511 Balé Bagassi Niaga 100% 388 Balé Bagassi Ouanga 100% 321 Balé Bagassi Pahin 100% 1032 Balé Bagassi San 100% 739 Balé Bagassi Sayaro 100% 1120 Balé Bagassi Sipohin 100% 552 Balé Bagassi Yaro 100% 1234

Laa laa ( Boni région) Balé Bagassi Assio 100% 728

Balé Bagassi Vy 100% 2880

Balé Pâ Boro 100% 992

Balé Pâ Didie 100% 963 Balé Pâ Kopoï 100% 1709

Balé Pâ Pâ 60% 3030

Balé Pâ Voho 100% 1044 Balé Pompoï Battiti 100% 411 Tuy Boni Bansié (included under

Boni)

100%

Tuy Boni Boni 100% 6122 Tuy Boni Bouahoun 100% 2969 Tuy Boni Manboué (included under

Boni)

100%

Dialect Province Department Village Estimated Percentage

of Bwa

Population

Villages that are not specifically part of the Bagassi dialect, but which may be able to use their materials

Balé Fara Naouya (seems to be related to the Bagassi dialect)

100% 502

Balé Yaho Bondo 100% 1034 Balé Yaho Madou 100% 1156 Balé Yaho Mamou 100% 1888 Balé Yaho Maoula 100% 363 Balé Yaho Mina 100% 457 Balé Yaho Mouni 100% 796 Tuy Houndé Karaba (part of Houndé?) 100% 2010

Total 45,812

&&Z Z

(coo) Balé Fara Kabourou 100% 2245

Balé Fara Laro 100% 1306 Balé Fara Pomain 50% 370 Balé Fara Toné 100% 1415 Sissili Niabouri Pourou 100% 198 Tuy Founzan Bonzan Bobo 50% 875 Tuy Founzan Founzan 20% 659 Tuy Founzan Kouloho 100% 2863 Tuy Founzan Kovio 40% 564 Tuy Founzan Lobougo 100% 1848 Tuy Founzan Lollio 40% 429 Tuy Koti Fafo 60% 1192 Tuy Koti Indeni 40% 566 Tuy Koti Koti 80% 3014

Tuy Koti Poa 60% 444

Total 17,988

Dakwi (dakoo) Bougouriba Bondigui Mougué 316

Dialect Province Department Village Estimated Percentage

of Bwa

Population

Tuy Koumbia Pe 100% 2512 Tuy Koumbia Sébédougou 50% 642

Total 18,574

Unidentified Balé Fara Bouzourou 33% 544

Balé Fara Sadon Bobo 100% 569 Balé Poura Poura-village 20% 1100 Sissili Niabouri Payalo 33% 403 Tuy Koti Kayao 100% 1661

Total 4,277

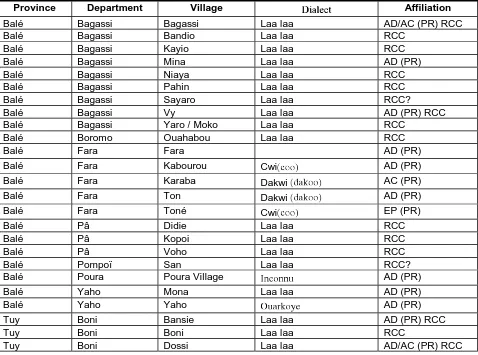

Table 1.2

Christian Congregations in the Southern Bwamu Region

List of Abbreviations AD : Assemblées de Dieu AC : Alliance Chrétienne

EP : Eglise Pentecôte RCC : Catholique

Province Department Village 'LDOHFW'LDOHFW Affiliation

Balé Bagassi Bagassi Laa laa AD/AC (PR) RCC Balé Bagassi Bandio Laa laa RCC

Balé Bagassi Kayio Laa laa RCC Balé Bagassi Mina Laa laa AD (PR) Balé Bagassi Niaya Laa laa RCC Balé Bagassi Pahin Laa laa RCC Balé Bagassi Sayaro Laa laa RCC?

Balé Bagassi Vy Laa laa AD (PR) RCC Balé Bagassi Yaro / Moko Laa laa RCC

Balé Boromo Ouahabou Laa laa RCC

Balé Fara Fara AD (PR)

Balé Fara Kabourou Cwi AD (PR) Balé Fara Karaba Dakwi AC (PR) Balé Fara Ton Dakwi AD (PR) Balé Fara Toné Cwi EP (PR) Balé Pâ Didie Laa laa RCC Balé Pâ Kopoi Laa laa RCC Balé Pâ Voho Laa laa RCC Balé Pompoï San Laa laa RCC? Balé Poura Poura Village AD (PR) Balé Yaho Mona Laa laa AD (PR)

Balé Yaho Yaho AD (PR)

Tuy Boni Bansie Laa laa AD (PR) RCC Tuy Boni Boni Laa laa RCC

Province Department Village 'LDOHFW'LDOHFW Affiliation

Tuy Boni Minou Laa laa AD (PR) RCC Tuy Founzan Bouzan Cwi Dakwi RCC

Tuy Founzan Founzan Dakwi AD (PR) RCC Tuy Founzan Koulotto Laa laa RCC

Tuy Founzan Kovio Cwi Dakwi AC (PR) RCC Tuy Founzan Lollio Cwi Dakwi AC (PR) RCC Tuy Houndé Baouhoun Laa laa AD (PR) Tuy Houndé Bouéré AD (PR) Tuy Houndé Dohouri AC (PR) Tuy Houndé Houndé AC (PR) RCC Tuy Houndé Karaba AC (PR)

Tuy Houndé Kari AC (PR)

Tuy Houndé Kieré AD (PR)

Tuy Houndé Koho AC (PR)

Tuy Houndé Sieni AC (PR)

Tuy Koti Fafo EP (PR) RCC

Tuy Koti Kayao EP (PR)

Tuy Koti Koti EP (PR) RCC

Tuy Koti Poa EP (PR) RCC

Tuy Koumbia Gombeledougou Dakwi AC (PR) Tuy Koumbia Kongolikan Dakwi AC (PR)

Table 1.3

Primary Schools in the Southern Bwamu Region18

Province Department Village Date Opened

Levels Total Enroll-ment

Girls Boys

Balé Bagassi Bagassi 1949 6 411 168 243

Balé Bagassi Bandio 1991 2 112 45 67

Balé Bagassi Bounou 1993 3 230 100 130

Balé Bagassi Koussaro 1993 1 58 21 37

Balé Bagassi Pahin 1986 3 119 48 71

Balé Bagassi Sayaro 1988 3 132 46 86

Balé Bagassi Vy 1958 5 305 115 190

Balé Bagassi Yaramoko(Yaro?) 1987 3 185 59 126

Balé Boromo Koho 1985 3 120 41 79

Balé Boromo Ouahabou 1958 6 348 125 223

Balé Fara Bouzourou 1986 3 83 36 47

Balé Fara Kabourou 1982 3 195 74 121

Balé Fara Laro 1986 3 113 31 82

Balé Fara Ton 1987 2 133 46 87

Balé Fara Toné 1962 3 159 45 114

Balé Pâ Kopoï 1962 3 186 57 129

Balé Pâ Pâ 1971 6 319 107 212

Balé Pâ Pâ 1990 2 106 27 80

Balé Poura Poura 1958 6 471 197 274

Balé Poura Poura 1986 6 488 229 259

Balé Poura Poura village 1985 3 164 55 109

Balé Yaho Madou 1989 1 79 21 58

Balé Yaho Mamou 1962 3 225 83 142

Balé Yaho Yaho 1951 6 408 157 251

Tuy Boni Boni 1984 3 135 50 85

Tuy Boni Boni 1957 6 454 165 289

Tuy Boni Dossi 1985 3 128 48 80

Tuy Founzan Bonzan Bwaba 1991 2 101 37 64

Tuy Founzan Kouloho-Lobougo 1985 3 126 24 102

Tuy Founzan Lollio 1990 2 92 38 54

Tuy Houndé Boho-Kari 1987 3 139 45 94

Tuy Houndé Bouahoum 1978 3 166 43 123

Tuy Houndé Bouéré 1985 3 169 45 124

Tuy Houndé Dankari 1984 2 101 33 68

Tuy Houndé Dohoun 1980 3 178 60 118

Province Department Village Date Opened

Levels Total Enroll-ment

Girls Boys

Tuy Houndé Karaba 1983 4 163 66 97

Tuy Houndé Kari 1975 3 200 62 138

Tuy Houndé Kiéré 1974 3 201 65 136

Tuy Koti Fafo 1978 3 123 30 93

Tuy Koti Indeni 1984 3 112 30 82

Tuy Koti Kayao 1989 3 153 49 104

Tuy Koti Koti 1979 5 245 72 173

Tuy Koti Poa 1991 2 113 34 79

Tuy Koumbia Dougoumato Son 1991 2 156 42 114

Tuy Koumbia Gombélédougou 1986 3 123 48 75

Tuy Koumbia Kongolikan / Dougoumato

1983 3 275 68 207

Tuy Koumbia Koumbia 1958 6 446 161 285

Tuy Koumbia Pê 1983 3 217 86 131

Tuy Koumbia Sébédougou 1982 3 196 81 115

Table 1.4

Middle and High Schools in the Southern Bwamu Region

Village Visited Closest Middle Schools Closest High Schools

Koumbia (Balé) Léo, Fara Léo

Kabourou (Balé) Fara Léo, Dano

Koti (Tuy) Dano Dano

Bonzan Bobo (Tuy) Dano Dano

Boni (Tuy) Houndé Boromo, Bobo-Dioulasso

Karaba (Tuy) Houndé Bobo-Dioulasso

Sébédougou (Tuy) Houndé Bobo-Dioulasso

Kongolikan (Tuy) Houndé Bobo-Dioulasso

Mamou (Balé) Bagassi Ouagadougou / Dédougou /

Table 1.5

CFJA locations in the southern Bwamu area: 1993–1994 (DFPP 1994)

Province Department Village Number of

Students

Balé Bagassi Pahin 20

Balé Fara Toné unknown

Bougouriba Bondigui Mougue 15

Tuy Boni Dossi 20

Tuy Founzan Kouloho 18

Tuy Houndé Kari 20

2 A Word List of Dialects in the Southern Bwamu Region (section 3.3)

Boni Kongolikan Koti Kabourou

Karaba Ouarkoye

003 homme

Koumbia Kongolikan Karaba Ouarkoye Koti Kabourou Mamou Sébédougou Boni Koti Kabourou Ouarkoye Koti Boni Mamou Kabourou Karaba

007 mère

Sébédougou

Koumbia Kongolikan Koti Kabourou Ouarkoye

! Kongolikan Karaba

009 garçon

Koti Kabourou

Karaba

011 grande soeur

Koumbia

%&% Kongolikan

% & Sébédougou

% Karaba

012 grand frère

' Koumbia

%& Kongolikan

013 petite soeur

+ Koumbia

%&$- Kongolikan

014 petit frère

+ Koumbia

%&$- Kongolikan

%%+ Karaba

015 chef

"# Kongolikan

017 guérisseur

Koti Kabourou

"-)- Kongolikan

"+ Karaba

"+ Boni

.+ Mamou

020 village

Koumbia Koti Boni Karaba Sébédougou

0 Koumbia Koti Kabourou

0 Boni

Koti Kabourou

$/ Boni

Karaba Ouarkoye

Sébédougou

Koti Kabourou

&" Ouarkoye

& Boni

Karaba Ouarkoye Koumbia

*, Kongolikan

Sébédougou

Koti Kabourou

Koti Kabourou

$"%& Koumbia Koti

$" Karaba

" Kongolikan

#" Mamou

$%+ Koumbia Koti Kabourou

Koti

Koti

036 calebasse

Koumbia Sébédougou Kongolikan

Ouarkoye

Koti Kabourou Boni

Koti Kabourou

" Kongolikan

Boni Koti Kabourou

Karaba Ouarkoye

046 gros mil

$ Koumbia

047 petit mil

Koumbia Koti Kongolikan Kabourou

Karaba Sébédougou Ouarkoye

Mamou

! Boni

048 gombo

Koumbia Koti Kabourou

Boni Mamou

Koumbia Koti Kabourou Karaba

050 sésame

Kongolikan Karaba Sébédougou

Mamou Koti Kabourou

$" Kongolikan

%&' Koti Kabourou

052 maïs

&$" Ouarkoye

($ Sébédougou

"" Ouarkoye