Bilateral ECT in Schizophrenia: A Preliminary Study

Worrawat Chanpattana, M.L. Somchai Chakrabhand, Wanchai Buppanharun,

and Harold A. Sackeim

Background: This preliminary study examined the effects

of electrical stimulus intensity on the speed of response

and efficacy of bilateral electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

in the treatment of schizophrenia.

Methods: Sixty-two patients with schizophrenia received

combination treatment with bilateral ECT and

flu-penthixol. Using a randomized, double-blind design, the

effects of three dosages of the ECT electrical stimulus

were examined. Patients were treated with a stimulus

intensity that was just above seizure threshold, two-times

threshold, or four-times threshold. Assessments of

out-come used the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, Global

Assessment of Functioning, and the Mini-Mental State

Exam.

Results: Thirty-three of sixty-two patients met remitter

criteria, including maintaining improvement over a

3-week stabilization period. The dosage groups were

equivalent in the number of patients who met remitter

criteria. The low-dose remitter group (n

5

11) received

more ECT treatments and required more days to meet

remitter status than both the twofold (n

5

11) and fourfold

remitter groups (n

5

11). There was no difference among

the groups in change in global cognitive status as assessed

by the Mini-Mental State Exam.

Conclusions: This preliminary study indicates that

treat-ment with high-dosage bilateral ECT speeds clinical

re-sponse in patients with schizophrenia. There may be a

therapeutic window of stimulus intensity in impacting on the

efficacy of bilateral ECT, which needs further study. A more

sensitive battery of cognitive tests should be used in future

research. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:222–228 © 2000

Soci-ety of Biological Psychiatry

Key Words: Electroconvulsive therapy, method, efficacy,

schizophrenia

Introduction

S

ince its inception, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has

been used to treat schizophrenia. Neuroleptic

medica-tions rapidly replaced ECT after their introduction in the

1950s. During the 1970s, when limitations in the efficacy

of neuroleptics and adverse effects from prolonged use

were recognized, interest in ECT as a treatment for

medication-resistant schizophrenia returned (Fink and

Sackeim 1996). A number of surveys in several countries

found that from 2.9% to 36% of patients receiving ECT

had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (Krueger and Sackeim

1995). This rate was reported to be 60% and 75% in Czech

(Baudis 1992) and Indian patients (Shukla 1981),

respectively.

Research on the use of ECT in schizophrenia has

been characterized by a variety of methodologic

limi-tations, including uncertain diagnostic criteria,

nonran-dom assignment to treatment groups, and lack of blind

and reliable clinical assessment (Krueger and Sackeim

1995). Nonetheless, the conclusions suggested in this

literature are that 1) ECT is effective in the treatment of

schizophrenia, especially among patients with acute

exacerbations, relatively short duration of illness, or

both; and that 2) combined ECT and neuroleptic

treat-ment is more effective than either ECT alone or

neuroleptic treatment alone (Chanpattana et al 1999a,

1999b; Fink and Sackeim 1996).

The interactive effects of stimulus intensity and

elec-trode placement on the efficacy of ECT in major

depres-sion is established (Sackeim et al 1987a, 1987b, 1993, in

press; Krystal et al 1998; McCall et al, in press). With

right unilateral ECT, the likelihood of clinical response in

major depression is highly dependent on the degree to

which stimulus dosage exceeds seizure threshold. With

both right unilateral and bilateral ECT, higher stimulus

intensity results in faster clinical improvement ( Nobler et

al 1997; Sackeim et al 1993, in press). The impact of

electrical dosage in moderating the efficacy of bilateral

ECT in schizophrenia is unknown. We hypothesized that

high-dosage bilateral ECT would enhance the speed of

clinical response in patients with schizophrenia.

From the Departments of Psychiatry (WC) and Preventive Medicine (WB), Srinakharinwirot University, Bangkok, and the Department of Mental Health, Nonthaburi (MLSC), Thailand, and the Department of Biological Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Departments of Psychiatry and Radiology, College of Physicians & Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, New York (HAS).

Address reprint requests to Worrawat Chanpattana, M.D., Department of Psychia-try, Srinakharinwirot University, 681Samsen, Dusit Bangkok 10300, Thailand. Received October 1, 1999; revised January 10, 2000; accepted January 19, 2000.

© 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry 0006-3223/00/$20.00

Methods and Materials

Subjects

Sixty-seven patients (30 men, 37 women) with acute psychotic exacerbations and who met the DSM-IV criteria for schizophre-nia (American Psychiatric Association 1994) were referred for ECT because of failure to respond to neuroleptic treatment. Psychiatric diagnosis was based on the consensus of three psychiatrists and also had to concur with the patients’ medical records. Diagnosis in the medical records had to be consistent throughout the episode of illness. Other inclusion criteria were a minimum pretreatment score of 37 on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, 18 items, rated 0 – 6; Overall and Gorham 1962), and subjects had to be between ages 16 and 50 years. Patients were excluded if they received treatment with depot neuroleptics or ECT during the previous 6 months, psychotic disorders due to a general medical condition, neurologic illness, alcohol or other substance abuse, or serious medical illness. All patients had normal results of complete blood count, serum electrolytes, and electrocardiography. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Srina-kharinwirot University and the National Review Board of Re-search Studies in Humans of Thailand. After complete descrip-tion of the study and the opportunity to ask quesdescrip-tions, voluntary written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their guardians.

Twenty-three patients (10 men, 13 women) were randomized to receive low-dosage bilateral ECT (dose just above the seizure threshold), 23 patients (11 men and 12 women) were assigned to the twofold seizure threshold group, and 21 patients (9 men and 12 women) were assigned to the fourfold seizure threshold group. Five patients dropped out from this double-blind compar-ative study—two from the low-dose group, two from the twofold seizure threshold group, and one from the fourfold seizure threshold group—leaving 62 patients in the study.

Procedures

Neuroleptic medications prescribed before the study were dis-continued without a washout period. Flupenthixol was started before the first ECT session and was continued throughout the study. The dosage schedule of flupenthixol was fixed at 12 mg/day ($600 mg chlorpromazine [CPZ] equivalents) during the first week, 18 mg/day ($900 mg CPZ equivalents) for the days 8 –10, and 24 mg/day ($1200 mg CPZ equivalents) thereafter, depending on tolerability. All patients were treated between 18 –24 mg/day of flupenthixol, which has a half-life of approx-imately 35 hours, leading to steady state at 7 days. Benzhexol (4 –15 mg/day) was used to manage extrapyramidal symptoms, with dosage titrated on a clinical basis. Diazepam (10 mg/day) was prescribed to control agitation on a PRN basis and was withheld at least 8 hours before each ECT treatment.

Electroconvulsive therapy was administered three times per week. The ECT devices were a Thymatron DGx and MECTA SR 1. Each patient was treated with only one ECT device (two different hospitals participated in the study, each using a different device). Thiopental (2– 4 mg/kg) was used at the lowest dosage to induce general anesthesia, minimizing effects on seizure

threshold. Succinylcholine (0.5–1 mg/kg) served as the muscle relaxant. Atropine (0.4 mg intravenously) was administered approximately 2 min before the anesthetic. Patients were oxy-genated from anesthetic administration until postictal resumption of spontaneous respiration. Bitemporal bilateral electrode place-ment was used throughout. The tourniquet method and two channels of prefrontal electroencephalogram (EEG) were used to assess seizure duration. An adequate seizure was defined as a tonic-clonic motor convulsion occurring bilaterally for at least 30 sec, plus EEG evidence of a cerebral seizure. Reliance on the duration of motor manifestations to define adequacy was con-servative because EEG ictal expression typically outlasts motor expression for several seconds (Sackeim et al 1991; Warmflash et al 1987). Grossly suprathreshold stimulation can result in reduced seizure duration, below conventional cutoffs for “ade-quacy” (American Psychiatric Association Task Force, in press; Sackeim et al 1991); however, it was felt that the stimulus intensities used here, all adjusted relative to initial seizure threshold, would be insufficient to result in a marked shortening of seizure duration. In each treatment one adequate seizure was elicited.

Using the empirical titration technique (Sackeim et al 1987c), seizure threshold was quantified at the first two treatment sessions and was defined as the minimal electrical stimulus (in millicoulombs) to produce a motor seizure duration of at least 30 sec. For the MECTA SR 1, the titration schedule followed that used by Coffey et al (1995). With the Thymatron DGx, the first stimulus at the first treatment session was 10% of total charge. If this failed to produce an adequate seizure, electrical dosage was increased in 10% steps. This approach roughly matched the charge delivered by the MECTA SR 1 and Thymatron DGx at each step in the titration schedule. There was a limit of four stimulations in a session, but the maximal number administered in this sample was three. A 40-sec interval elapsed between each step in the titration, and no patient required additional thiopental. At the second treatment session, patients were stimulated with an intensity 5% below the first treatment’s threshold value. If this failed to produce an adequate seizure, the first session’s value was adopted as the initial seizure threshold (ST). Patients were then stimulated with the assigned electrical stimulus charge (either 1, or 2, or 43ST). If the decreased intensity produced an adequate seizure, this new value was taken as the ST, and there was no further stimulation in that session. At subsequent sessions in the 1 ST group, if needed, electrical stimulus dosage was increased by one step to achieve an adequate seizure. In the 2 ST and 4 ST groups, the duration of motor seizures was ignored during the three subsequent sessions. Afterward, if the seizure was shorter than 30 sec, the delivered charge was increased by one step. At the 10th treatment session, all patients were reassessed for ST. The stimulus charge was then adjusted based on the assigned ST group or to the maximal charge settings of the device.

Clinical Evaluation

on to a 3-week stabilization period (Chanpattana 1998, 1999; Chanpattana et al 1999a, 1999b). The stabilization period com-prised the following treatment schedule: 3 ECT treatments in the first week, then once a week for the second and third weeks (during which BPRS scores of 25 or less had to be consistently maintained). If BPRS scores rose above 25 at any time during this period, and the total number of ECT treatments was less than 20, patients returned to the acute ECT treatment regimen and repeated the acute phase and stabilization schedules again. Patients with BPRS scores above 25, who had already received 20 ECT treatments, were considered ECT nonresponders. The same considerations applied to the patients who had not shown significant improvement (BPRS . 25) until their 20th ECT treatment. Thus, ECT responders were patients who completed the 3-week stabilization period during which the BPRS score assessed before each treatment was consistently 25 or less.

Measures used to assess study outcome were 1) BPRS as-sessed before each treatment, during the acute and stabilization periods, and end of the study (1 week after the last treatment); 2) Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) assessed before each acute treatment and at the end of the study; and 3) the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE, Thai version; Kongsakon and Vanichtanom 1994) assessed at the same time as the BPRS. Three psychiatric nurses served as raters, masked to the treatment conditions. Each patient was rated by the same nurse. These raters underwent training for 12–24 months. Interrater reliability was assessed. Each rater provided ratings simultaneously on 10 patients. Each patient was interviewed by a psychiatrist for 20 min. The correlations of BPRS scores between each rater and the psychiatrist indicated strong reliability (0.93, 0.96, and 0.97).

Statistical Analyses

The results are expressed as mean6SD. Seizure threshold data were analyzed after logarithmic transformation to improve the normality of the data distribution (Sackeim et al 1987b). For discontinuous data, chi-square tests were used to test for differ-ences among the groups. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare the three treatment groups in continuous demographic and clinical variables. Significant main effects of treatment group were followed by Scheffe´ post hoc comparisons to identify pair-wise differences. The groups were compared in speed of response by conducting ANOVAs on the number of ECT treatments and the number of days in ECT treatment for patients who met initial and final remitter criteria. In addition, across the total sample, Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted on these measures, treating ECT nonresponders as censored observations.

Results

Sixty-seven patients with schizophrenia received ECT.

Five patients dropped out, leaving 62 patients in the study.

All 5 patients who dropped out withdrew consent,

report-ing fear of ECT, despite receivreport-ing basic information about

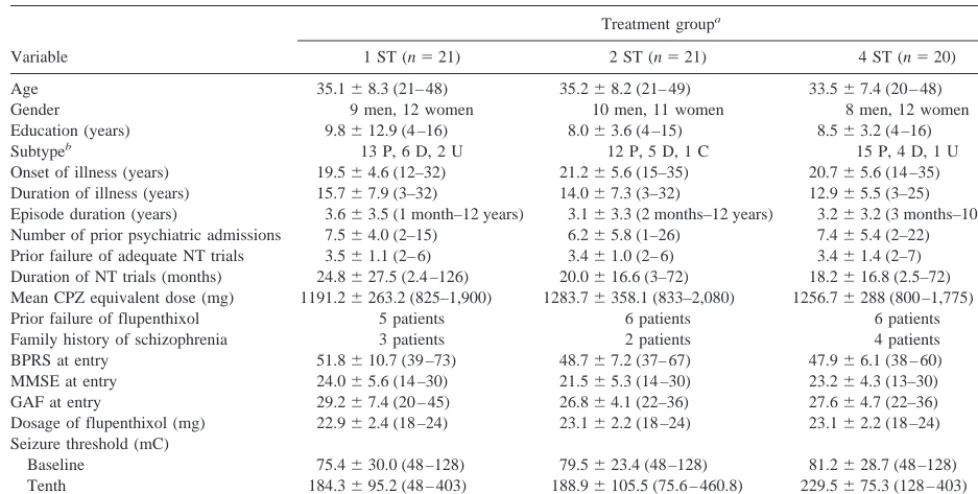

ECT and schizophrenia. Table 1 presents demographic and

clinical features of the 62 patients as a function of

treatment condition. There were no significant differences

among the three treatment groups in any variable.

Thirty-three patients maintained remitter status through

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Features of the Sample

Variable

Treatment groupa

1 ST (n521) 2 ST (n521) 4 ST (n520)

Age 35.168.3 (21– 48) 35.268.2 (21– 49) 33.567.4 (20 – 48)

Gender 9 men, 12 women 10 men, 11 women 8 men, 12 women

Education (years) 9.8612.9 (4 –16) 8.063.6 (4 –15) 8.563.2 (4 –16)

Subtypeb 13 P, 6 D, 2 U 12 P, 5 D, 1 C 15 P, 4 D, 1 U

Onset of illness (years) 19.564.6 (12–32) 21.265.6 (15–35) 20.765.6 (14 –35) Duration of illness (years) 15.767.9 (3–32) 14.067.3 (3–32) 12.965.5 (3–25)

Episode duration (years) 3.663.5 (1 month–12 years) 3.163.3 (2 months–12 years) 3.263.2 (3 months–10 years) Number of prior psychiatric admissions 7.564.0 (2–15) 6.265.8 (1–26) 7.465.4 (2–22)

Prior failure of adequate NT trials 3.561.1 (2– 6) 3.461.0 (2– 6) 3.461.4 (2–7) Duration of NT trials (months) 24.8627.5 (2.4 –126) 20.0616.6 (3–72) 18.2616.8 (2.5–72) Mean CPZ equivalent dose (mg) 1191.26263.2 (825–1,900) 1283.76358.1 (833–2,080) 1256.76288 (800 –1,775)

Prior failure of flupenthixol 5 patients 6 patients 6 patients

Family history of schizophrenia 3 patients 2 patients 4 patients BPRS at entry 51.8610.7 (39 –73) 48.767.2 (37– 67) 47.966.1 (38 – 60) MMSE at entry 24.065.6 (14 –30) 21.565.3 (14 –30) 23.264.3 (13–30) GAF at entry 29.267.4 (20 – 45) 26.864.1 (22–36) 27.664.7 (22–36) Dosage of flupenthixol (mg) 22.962.4 (18 –24) 23.162.2 (18 –24) 23.162.2 (18 –24) Seizure threshold (mC)

Baseline 75.4630.0 (48 –128) 79.5623.4 (48 –128) 81.2628.7 (48 –128) Tenth 184.3695.2 (48 – 403) 188.96105.5 (75.6 – 460.8) 229.5675.3 (128 – 403) Increment 107.5684.8 (0 –323) 108.86111.0 (0 – 412.8) 147.8686.0 (48 –355.2)

aTreatment groups: 1 ST, dose just above seizure threshold (ST); 2 ST, 23ST; 4 ST, 43ST. bSubtype: P, paranoid; D, disorganized; C, catatonia; U, undifferentiated.

the stabilization period and were classified as ECT

re-sponders. There was no difference in response rate among

the three treatment groups [52%, 52%, and 55% for 1 ST,

2 ST, and 4 ST, respectively;

x

2(2)

5

0.04, ns]. There

were 11 patients in each treatment group. The three

treatment groups did not differ in any of the demographic

or clinical variables listed in Table 1.

Table 2 presents the treatment features for the remitted

patients as a function of the ECT conditions. Compared

with remitters in the low-dosage group, remitters in both

the 2 ST and 4 ST groups received fewer ECT treatments

at the time of first significant clinical improvement,

defined as a BPRS score of 25 or less [F(2,30)

5

18.70,

p

,

.0001; 1 ST vs. 2 ST, p

5

.002; 1 ST vs. 4 ST, p

,

.0001] and had fewer days in ECT treatment [F(2,30)

5

16.35, p

,

.0001; 1 ST vs. 2 ST, p

5

.003; 1 ST vs. 4 ST,

p

,

.0001]. The 2 ST and 4 ST groups did not differ

significantly in these measures (Table 2), although the

pattern of means suggested more rapid onset of

improve-ment in the 4 ST relative to the 2 ST group (p

5

.19).

At the end of study, the same effects were manifest.

Remitters in both the 2 ST and 4 ST groups received fewer

treatments [F(2,30)

5

18.70, p

,

.0001; 1 ST vs. 2 ST,

p

,

.002; 1 ST vs. 4 ST, p

,

.0001] and had fewer days

in treatment than remitters in the low-dosage group

[F(2,30)

5

16.29, p

,

.0001; 1 ST vs. 2 ST, p

5

.003; 1

ST vs. 4 ST, p

,

.0001]. The 2 ST and 4 ST groups did not

differ in these measures (Table 2), although again the 4 ST

group averaged three fewer treatments than did the 2 ST

group (p

5

.13). Including the stabilization phase,

remit-ters in the 1 ST group on average received 18.64 (SD

5

4.95) treatments, whereas the 2 ST remitters averaged

12.46 (SD

5

3.75) treatments and the 4 ST remitters

averaged 9.18 (SD

5

1.47) treatments.

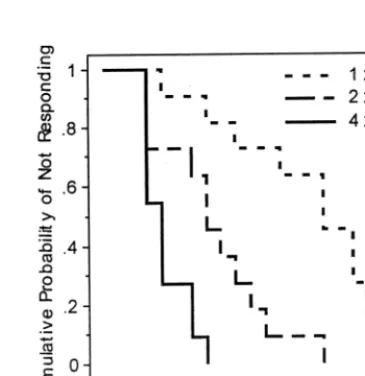

These effects were reexamined using survival analysis

on the total sample of 62 patients, with ECT

nonre-sponders treated as censored observations. The survival

analysis on number of ECT treatments administered

yielded a significant effect of treatment group [Figure 1;

log-rank

x

2(2)

5

25.00, p

,

.0001], as did the analysis of

the number of days in treatment [log-rank

x

2(2)

5

24.38,

p

,

.0001].

The extent of clinical improvement was comparable

among the three remitter groups. At the end of the study,

the 1 ST, 2 ST, and 4 ST remitter groups, respectively, had

62.6%, 60.8%, and 65.6% reductions in BPRS scores and

55.5%, 66.7%, and 55.8% increases in GAF scores. In the

total sample, ANOVAs were conducted on the percentage

change from baseline to study exit in BPRS, GAF, and

MMSE scores, with treatment group and remitter status as

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier survival plot for cumulative probability of nonresponse as a function of the number of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) treatments. Groups were treated just above seizure threshold (13ST), two times above threshold (23ST), or four times above threshold (43ST).

Table 2. Treatment Features of Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) Remitters

Variable

Treatment Groupa

1 ST (n511) 2 ST (n511) 4 ST (n511) Seizure threshold (mC)

First 68.4616.1 (48 – 80) 83.2623.3 (48 –128) 77.3629.1 (48 –128) Tenth 179.5697.3 (80 – 403) 222.5693.8 (126 – 403) 224655.4 (192–288) Average charge (mC per session)

Sessions 2–9 118.4647.1 (68 –196) 195.6632.9 (151–259) 372.2666.5 (245– 461) Sessions 11– end 254.66131 (128 –533) 413.16139 (230 –576) 576 all At first improvement

No. of ECT treatments 13.665.0 (4 –18) 7.563.8 (3–15) 4.261.5 (3–7) Days of treatment 35.4616.3 (7–58) 16.4611.9 (4 – 42) 7.063.6 (4 –14) At the end of study

No. of ECT treatments 18.665.0 (9 –23) 12.563.8 (8 –20) 9.261.5 (8 –12) Days of treatments 56.4616.3 (28 –79) 37.5612.0 (25– 63) 28.063.6 (25–35)

Valus are given in mean6SD (range). mC, millicoulombs.

between-subject factors. In the ANOVA on change in

BPRS scores there was only a main effect of remitter

status [F(1,56)

5

102.37, p

,

.0001]. Similarly, there was

only a main effect of remitter status in the ANOVA on

change in GAF scores [F(1,56)

5

18.23, p

,

.0001]. This

indicated that the treatment groups were equivalent in the

degree of change in symptoms and functional status. The

ANOVA on MMSE scores produced no significant

ef-fects, indicating that change in global cognitive status was

independent of treatment condition and remitter status.

In the total sample, the three treatment groups did not

differ in initial seizure threshold [F(2,59)

5

0.40, p

5

.67]

or in the percentage increase in threshold from the first to

tenth treatment [F(2,47)

5

0.79, p

5

.46; Table 1].

Patients who did or did not achieve remitter status did not

differ in initial seizure threshold [t(60)

5

0.45, p

5

.65] or

in the increase in threshold [t(48)

5

0.41, p

5

.68].

Although there is some evidence that response to ECT in

major depression is associated with a larger cumulative

seizure threshold increase (Sackeim 1999; Sackeim et al

1987b), this does not appear to be the case in

schizophrenia.

Discussion

This study found that speed of clinical response to bilateral

ECT in patients with schizophrenia is influenced by the

degree to which stimulus dosage exceeds seizure

thresh-old. Both of the high-dosage groups had more rapid

improvement than did the low-dosage group. The findings

parallel the results reported in patients with major

depres-sion ( Nobler et al 1997; Ottosson 1960; Robin and De

Tissera 1982; Sackeim et al 1993, in press). This is of

clinical importance because ECT is frequently used when

rapid improvement is needed. This was the first ECT study

examining the effect of stimulus intensity in patients with

schizophrenia.

Dosage factors, which are known to have greater impact

on the efficacy of right unilateral ECT, may also influence

the therapeutic properties of bilateral ECT. In major

depression, Ottosson (1960) examined the effects of

stim-ulus dose intensity on the efficacy of bilateral ECT.

Although there was no effect of dosage on response rate,

speed of symptom reduction was faster in patients who

received a stimulus intensity that was markedly

suprath-reshold. Cronholm and Ottosson (1963) reported that

low-intensity, ultra-brief pulse, bilateral ECT was less

effective than higher intensity, sinusoidal waveform,

bi-lateral ECT. Robin and De Tissera (1982) found that with

bilateral ECT, high-intensity brief-pulse or chopped sine

wave stimulation resulting in faster clinical improvement

than did low-intensity brief-pulse stimulation. Sackeim et

al (1993) randomly assigned patients to four treatment

conditions: low-dosage right unilateral ECT, high-dosage

right unilateral ECT, low-dosage bilateral ECT, and

high-dosage bilateral ECT. They found that regardless of

electrode placement, the high-dosage groups had more

rapid improvement than did the low-dosage groups. In

addition, low-dosage right unilateral ECT had poor

effi-cacy. In another four-group study, Sackeim et al (in press)

found that markedly suprathreshold (6

3

ST) right

unilat-eral ECT and moderate dosage (2.5

3

ST) bilateral ECT

were more effective and resulted in more rapid

improve-ment than lower intensity (1.5

3

ST and 2.5

3

ST) right

unilateral ECT. Thus, in studies of major depression, there

have been repeated findings that stimulus intensity

im-pacts on speed of clinical response. This study extends this

observation to patients with schizophrenia.

Analyses restricted to the remitter sample and survival

analyses of the total sample both supported the conclusion

that higher stimulus intensity resulted in more rapid

improvement in patients with schizophrenia. The analyses

in the remitter sample were particularly critical because

comparisons of speed of clinical improvement are most

relevant when restricted to patients who actually respond

(Laska and Siegel 1995; Nobler et al 1997). This approach

also avoids confounding likelihood of response (efficacy)

with speed of response (efficiency). There was no

evi-dence in this study that the stimulus-intensity conditions

differed in likelihood of response or degree of

symptom-atic improvement.

An unusual aspect of this study was the use of a 3-week

stabilization period as a screening method to identify

remitters (Chanpattana 1998, 1999; Chanpattana et al

1999a, 1999b). The stabilization period started

immedi-ately after the first sign of significant clinical improvement

(BPRS

#

25). Stability of clinical symptoms across these

3 weeks was required for classification as an ECT remitter.

Therefore, ECT remitters in this study maintained clinical

improvement for a substantial period of time.

This preliminary study had a number of limitations. A

washout period for previous antipsychotic medications

was not used because all study patients were in psychotic

exacerbations, and many patients were difficult to manage.

Lack of a washout may have had a substantial effect on the

patient’s initial seizure threshold because many patients

had prior treatment with low potency neuroleptics

(Sack-eim et al 1991). In contrast, all patients were treated with

flupenthixol, a typical neuroleptic with a potency about

1.5 times that of haloperidol. A fixed titration schedule of

flupenthixol dosage was used to minimize variability in

effects on seizure threshold.

the episode of illness. Theoretically, the inclusion in the

sample of patients with depressive or manic disorders

could account for the concordance of the results with

similar studies major depression. The relatively high

representation of female patients might suggest this

pos-sibility. That the patients presented with schizophrenia is

supported by the average episode duration of

approxi-mately 3.5 years (Table 1) and relatively low baseline

scores on the BPRS items of depressive mood,

grandios-ity, and excitement, coupled with high scores on

tradi-tional BPRS positive symptoms of psychosis (data not

shown).

It is well documented that ECT produces cognitive

impairment (American Psychiatric Association Task

Force, in press; Sackeim 1992). There were no differences

among the treatment groups or among ECT responders

and nonresponders in change in MMSE scores. Although

this suggests that the dosage conditions did not differ in

changes in global cognitive status, the MMSE is a measure

insensitive to the characteristic effects of ECT on

antero-grade and retroantero-grade memory (Sobin et al 1995). In major

depression, there is evidence that higher stimulus intensity

and longer courses of ECT treatment can result in more

severe transient cognitive side effects (Sackeim 1992;

Sackeim et al 1993). It will be important in future research

to use more sensitive neuropsychologic measures and

determine in patients with schizophrenia whether the

enhancement in speed of response due to higher stimulus

intensity offsets a detrimental effect of cognitive function.

In summary, this preliminary study indicates that in

patients with schizophrenia, electrical dosage impacts on

the speed of clinical response to bilateral ECT. Both the

groups treated at twice and four times seizure threshold

had more rapid improvement than did the low-dosage

group, who were treated just above seizure threshold.

Future research should examine the effects of high-dosage

bilateral ECT on cognitive functions, which should be

assessed

with

a

comprehensive

neuropsychological

battery.

Supported in part by Grant No. BRG 3980009 from the Thailand Research Fund (WC) and Grant No. R37 MH35636 from the National Institute of Mental Health (HAS). The authors thank Wiwat Yatapoot-anon, M.D., for technical support and the nursing staff of the Srithunya mental hospital.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994): Diagnostic and

Sta-tistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC:

American Psychiatric Press.

American Psychiatric Association Task Force (in press): The

Practice of ECT: Recommendations for Treatment, Training

and Privileging, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American

Psychi-atric Press.

Baudis P (1992): Elektrokonvulsini lecba v Ceske republice v letech 1981–1989. Cesk Psychiatr 88:41– 47.

Chanpattana W (1997): Continuation ECT in schizophrenia: A pilot study. J Med Assoc Thai 80:311–318.

Chanpattana W (1998): Maintenance ECT in schizophrenia: A pilot study. J Med Assoc Thai 81:17–24.

Chanpattana W (1999): The use of the stabilization period in electroconvulsive therapy research in schizophrenia: I. A pilot study. J Med Assoc Thai 82:1193–1199.

Chanpattana W, Chakrabhand S, Kongsakon R, Techakasem P, Buppanharun W (1999a): The short-term effect of combined ECT and neuroleptic therapy in treatment-resistant schizo-phrenia. J ECT 15:129 –139.

Chanpattana W, Chakrabhand S, Sackeim HA, Kitaroonchai W, Kongsakon R, Techakasem P, et al (1999b): Continuation ECT in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: A controlled study.

J ECT 15:178 –192.

Coffey CE, Lucke J, Weiner RD, Krystal AD, Aque M (1995): Seizure threshold in electroconvulsive therapy: I. Initial seizure threshold. Biol Psychiatry 37:713–720.

Cronholm B, Ottosson JO (1963): Ultrabrief stimulus technique in electroconvulsive therapy, II. Comparative studies of therapeutic effects and memory disturbance in treatment of endogenous depression with the Elther ES electroshock ap-paratus and Siemens Konvulsator. J Nerv Ment Dis 137:268 – 276.

Fink M, Sackeim HA (1996): Convulsive therapy in schizophre-nia? Schizophr Bull 22:27–39.

Kongsakon R, Vanichtanom R (1994): Assessment of the differ-ences in MMSE between neurological, psychiatric patients and normal population. J Rajwithi Hosp 5:99 –106.

Krueger RB, Sackeim HA (1995): Electroconvulsive therapy and schizophrenia. In: Hirsch S, Weinberger D, editors.

Schizophrenia. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press,

503–545.

Krystal AD, Coffey CE, Weiner RD, Holsinger T (1998): Changes in seizure threshold over the course of electrocon-vulsive therapy affect therapeutic response and are detected by ictal EEG ratings. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 10:178 –186.

Laska EM, Siegel C (1995): Characterizing onset in psychophar-macological trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 31:29 –35. McCall WV, Reboussin DM, Weiner RD, Sackeim HA (in

press): Titrated, moderately suprathreshold versus fixed, high dose RUL ECT: Acute antidepressant and cognitive effects.

Arch Gen Psychiatry.

Nobler MS, Sackeim HA, Moeller JR, Prudic J, Petkova E, Waternaux C (1997): Quantifying the speed of symptomatic improvement with electroconvulsive therapy: Comparison of alternative statistical methods. Convuls Ther 13:208 –221. Ottosson JO (1960): Experimental studies of the mode of action

of electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 145:1–141.

Overall JF, Gorham DR (1962): The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 10:799 – 812.

comparison of the therapeutic effects of low and high energy electroconvulsive therapies. Br J Psychiatry 141:357–366. Sackeim HA (1992): The cognitive effects of electroconvulsive

therapy. In: Moos WH, Gamzu ER, Thal LJ, editors.

Cogni-tive Disorders: Pathophysiology and Treatment. New York:

Marcel Dekker, 183–228.

Sackeim HA (1999): The anticonvulsant hypothesis of the mechanisms of action of ECT: Current status. J ECT 15:5–26. Sackeim HA, Decina P, Kanzler M, Kerr B, Malitz S (1987a): Effects of electrode placement on the efficacy of titrated, low-dose ECT. Am J Psychiatry 144:1449 –1455.

Sackeim HA, Decina P, Portnoy S, Neeley P, Malitz S (1987b): Studies on dosage, seizure threshold, and seizure duration in ECT. Biol Psychiatry 22:249 –268.

Sackeim HA, Decina P, Prohovnik I, Malitz S (1987c): Seizure threshold in electroconvulsive therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44:355–360.

Sackeim HA, Devanand DP, Prudic J (1991): Stimulus intensity, seizure threshold, and seizure duration: Impact on the efficacy

and safety of electroconvulsive therapy. Psychiatr Clin North

Am 14:803– 843.

Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Kiersky JE, Fitzsimons L, Moody BJ, et al (1993): Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. N Engl J Med 328: 839 – 846.

Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Nobler MS, Lisanby SH, Peyser S, et al (in press): A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bilateral and right unilateral ECT at different stimulus intensities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Shukla GD (1981): Electroconvulsive therapy in a rural teaching

general hospital in India. Br J Psychiatry 139:569 –571. Sobin C, Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Moody BJ,

McElhiney MC (1995): Predictors of retrograde amnesia following ECT. Am J Psychiatry 152:995–1001.