Bilateral Gluteal Fasciocutaneous Flap for Reconstruction of

Large Sacral SCC Defect

Elvida Christi*, I.B Suryawisesa**, I.B TjakraManuaba***

*Surgery Department, Faculty of Medicine Udayana University **Oncology Surgery Department - Sanglah Hospital, Denpasar

Abstract

Introduction : Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant tumour that arises from the keratinizing cells of the epidermis or its appendages. It is locally invasive and has the potential to metastase to other organ of the body. The incidence of SCC is about 10,000 per year in England and Wales. We reported a patient with a large SCC on the sacral region. The tumor was very large and the location was very risky to tension while the patient sitting or binding. Therefore, it needs to be selective in choosing the flap to close the defect. So, we decided to perform bilateral gluteal fasciocutaneuos flap.

Case report : Male patients 65 years of age, present with a lump on buttocks since 8 years ago. The lump initially small, but gradually enlarged and when the patient comes, the tumor measuring 12 x 9 cm accompanied by ulcers that smells and accompanied by pain in the area around the lump. Then we did a wide excision and bilateral gluteal fasciocutaneous flap to close the defect.

Conclusion : The case reported a difficulty in reconstruction to the tumor location. Skin graft/flap was not possible in this patient. Due to the anatomic site of the tumor, fasciocutaneous or myocutaneous flap (e.g :advanceflap, propeller flap or rotational flap). Was preferred Bilateral gluteal fasciocutaneous flap was performed in this patient. The patient showed adequate wound healing, well granulation and patient has been mobile.

Introduction

With a lifetime incidence of approximately 10% in the general population, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) is the second most common type of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Most CSCCs are benign and can be completely eradicated by surgery procedure.

Anatomy of gluteal flap

Gluteus Maximus :

1. Most superficial gluteal muscle 2. Origin

- Gluteal line of the posterior ileum and sacrum

- Sacrotuberous ligament 3. Insertion

- Greater tuberosity of the femur - Iliotibial band of fascia lata

Vascular supply :

1. Type III vascular supply : a.2 dominant pedicles

- Inferior gluteal arteries - From the internal iliac artery b. Both are deep to gluteus

c. Above and below inferior piriformis d. 2 minor pedicles at area of insertion :

- First perforator or profundafemoris - Two or three intermuscular branches of

the lateral femoral circumflex vessels

2. Major pedicles :

a. Superior gluteal arteries b. Inferior gluteal arteries c. From the internal iliac arteries

d. Pass superior and inferior to piriformis

Nerve supply : 1. Motor

a. Inferior gluteal nerve

b. Enters with inferior gluteal artery 2. Sensory

a. To skin S1-3 medially

b. L1-3 laterally

c. Posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh (S1-2)

- Supplies the inferior buttocks and posterior thigh

- This is can be included in the posterior thigh flap (neurosensory flap)

Muscle function :

1. Essential in ambulatory patients - Must preserve at least half 2. Extends hips

- Most powerful extensor of the hip

3. Rotates the thigh laterally

4. Important for running, jumping, climbing, stabilizes the pelvis and hip

There is so many procedure used to reconstruction the defect at sacral. Gluteal perforator flaps and fasciocutaneous rotation flaps are comparable for managing sacral pressure sores. Both can be considered a first-line option. Gluteal FR flap reconstructions can be performed without microsurgical dissection, and re-rotation is feasible in the event of sore recurrence. The authors suggest using gluteal fasciocutaneous rotation flaps in patients with a high risk of sore recurrence.

The gluteus muscle is an ideal flap for reconstructing the dead space of large perineal defects. Modification of this flap with a buttock rotation flap based on the skin perforators provides a versatile option for tension-free skin closure of the perineal wound.

The sensory lumbo-gluteal flap is useful for

the reconstruction of sacral decubitus ulcers if buttock sensation is intact, and may be best designed to avoid extension beyond the gluteal fold.

Case report

A male patients 65 years of age, present with a lump on buttocks for 8 years. The lump initially small, but gradually enlarged and when the patient comes, the resultant sacral defect measured 12 x 9 cm accompanied by ulcers that smells and accompanied by pain in the area around the lump. Incisional biopsy was performed and the histological findings confirmed the diagnosis of Well Differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Then we did a wide excision and reconstruction with bilateral gluteal fasciocutaneous flap to close the defect.

E

D

B

A

C

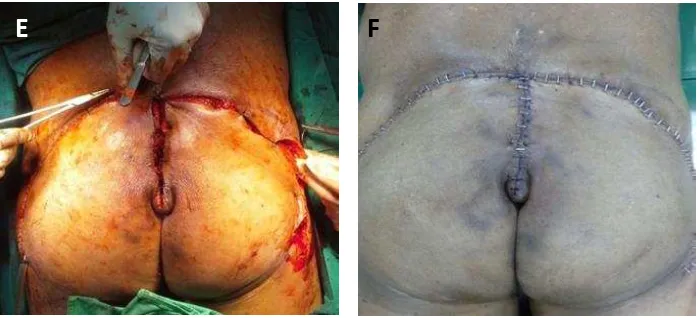

Figure A. Patient. SCC of the sacrum in a 65-year-old male patient. B. Resultant sacral defectmeasuring 9 by 12 cm. C,D,E. Bilateral Glutealcutaneous flap based on the inferior gluteal vessels. Arrow marks the perforator supplying the fascio-cutaneous flap. F. Tension free closure of the sacral defect resulted in a well healed scar.

Discussion

Squamous-cell carcinoma or squamous cell cancer (SCC or SqCC) is a cancer of a kind of epithelial cell, the squamous cell.1,2 These cells are the main part of the epidermis of the skin, and this cancer is one of the major forms of skin cancer. However, squamous cells also occur in the lining of the digestive tract, lungs, and other areas of the body, and SCC occurs as a form of cancer in diverse tissues, including the lips, mouth, esophagus, urinary bladder, prostate, lung, vagina, and cervix, among others.1-3 Despite sharing the name squamous cell carcinoma, the SCCs of different body sites can show tremendous differences in their presenting symptoms, natural history, prognosis, and response to treatment.5

SCC is a histologically distinct form of cancer. It arises from the uncontrolled multiplication of cells of epithelium, or cells showing particular cytological or tissue architectural characteristics of squamous cell differentiation, such as the presence of keratin, tonofilament bundles, or

desmosomes, structures involved in cell-to-cell adhesion.1,2

SCC is still sometimes referred to as "epidermoid carcinoma" and "squamous cell epithelioma", though the use of these terms has decreased. SCC typically initially occurs in the sixth decade of life (the 50s), but is most common in the eighth decade (the 70s).4,5 It is twice as prevalent in men as in women. People with darker skin are less at risk to develop SCC. Populations with fair skin, light hair, and blue/green/grey eyes are at highest risk of developing the disease. Frequent exposure to direct, strong sunlight without adequate topical protection also increases risk.1

Pressure sores, especially in the sacral area, pose challenges for reconstructive surgeons. Patients with pressure sores are usually paraplegic or bedridden, making the sores reluctant to heal, prone to recurrence, and difficult to reconstruct.1-3 The gluteus maximusmyocutaneous flap has been considered the workhorse flap for reconstructing sacral pressure sores.4-7

However, disadvantages of using this flap are limited flap mobility, sacrifice of muscle and increased blood loss. Yuhei et al.8,9 reported that the transferred muscle portion of the flap showed remarkable atrophic changes over the long term, and the recurrence rate was not significantly different from that with the fasciocutaneous flap.

With the advent of the perforator flap technique described by Koshima et al.,10 gluteal perforator (GP) flaps have recently gained popularity for reconstruction of sacral pressure sores. These flaps can use perforators that emerge from either the superior or inferior gluteal vessels. By dissecting perforators and completely islanding the flap, healthy tissue with a robust blood supply can be transferred freely without sacrificing the underlying muscle. Although a systematic review11 showed that there was no statistically significant difference with regard to recurrence or complication rates among musculocutaneous, fasciocutaneous and perforator flaps for pressure sore reconstruction, comparisons of GP flaps and fasciocutaneous rotation (FR) flaps specifically focussing on sacral pressure sore reconstruction have rarely been discussed.6-8

Musculocutaneous flaps have been the mainstay for treating sacral pressure sores because of their rich blood supply.4 However, the arc of rotation is limited and may cause much blood loss during flap elevation. This technique also causes donor-site morbidity, especially in ambulatory patients.Additionally, the transferred muscle undergoes significant atrophic degeneration with time, usually 1 year postoperatively. In experimental studies, pressure-induced hypoxia can cause muscle necrosis without skin necrosis in musculocutaneous flaps.12 Although Thiessenet

al.13 reported no differences in postoperative morbidity or recurrence between muscle and non-muscle flaps in univariate and multivariate analyses, Yamato et al.6 concluded that fasciocutaneous flaps have better long-term results than muscle or myocutaneous flaps when used for pressure sore reconstruction, and they suggested using fasciocutaneous flaps as a first choice for treating sacral pressure sores.7

Over the past few years, perforator flaps have gaine popularity. By completely islanding the skin paddle based on one or more perforators, the flap can be transferred with maximal freedom in a tension-free manner.9,10 For the first time in 1988, Kroll et al.14 published the use of perforator flaps for coverage of low midline defects, and Koshima et al.15 repaired sacral pressure sores using GP flaps and confirmed the reliability of the blood supply by Sacral pressure sore.

Large flaps can be transferred based on one or several perforators due to their rich vasculature. Furthermore, the versatility of the flap design allows it to adapt to the defect. The preservation of blood supply and muscle results in minimal donor-site morbidity. Most important of all, long pedicles of GPs enable tissue mobilization up to 12 cm in distance and achieve tension-free closure.16 Therefore, the use of perforator flaps can reduce the wound dehiscence rate. Although we observed a lower wound dehiscence rate in the GP group (6.45%) compared to the FR group (18.75%), the difference was not statistically significant. This outcome could be explained by the small number of cases in this study.

perforator venae comitantes, more tendinous intramuscular dissection and surgical expertiseare needed. Second, when a flap is designed in the propeller fashion based on a single perforator, although healthy and undamaged tissue can be transferred from a distant site, kinking of the perforator is possible and results in total flap failure, which rarely occurs with FR flaps.

In some study found good blood supply via the fascial plexus allows this flap to be raised easily without major complications, such as total flap loss. The circumference of the flap should be approximately 5-8 times the width of the defect to achieve tension-free distribution. According to many experience, the greatest benefit of fasciocutaneous flaps is that they are reusable.9 By creating an incision through the previous operative wound, the flap can be elevated and advanced in the event of partial necrosis or ulcer recurrence. Recently, Wong et al.10 and Lin et al.9 incorporated the concept of sparing the perforator in conventional FR flaps, which make them more reliable in vascularity and reusable for further reconstruction. However, reuse is generally not allowed for islandtype perforator flaps when flap necrosis or sore recurrence occurs, unless they are designed to be very large from the beginning. Fenget al.21 described the concept of free-style puzzle flaps to recycle a perforator flap. This innovative idea is valuable but has not yet been applied routinely to recurrent pressure sores. The recommended reconstructive options in this situation are perforator flaps or FR flaps from the contralateral buttock.

The use of either perforator flaps or FR flaps in sacral pressure sore reconstruction remains controversial. A recent systematic review discussing complications and recurrence

rates of musculocutaneous, fasciocutaneous and perforatorbased flaps for treatment of pressure sores revealed no significant differences among these flaps.11 In our study, variables such as operative time, defect size and blood loss were comparable in these two groups. There were also no significant differences between perforator and fasciocutaneous flaps with regard to re-operation, wound dehiscence, flap necrosis, infection, seroma, donor-site morbidity and overall complication rates. These results were similar to recent publications comparing perforator and fasciocutaneous flaps for pressure sore reconstruction.11,17 However, in our study, the overall complication rates for the perforator flap group (29%) and the fasciocutaneous flap group (37.5%) were higher than the complication rates (7e31%) reported in the literature. 12-14 This elevated incidence could be explained by the advanced age of our patients and multiple comorbidities, which made postoperative care difficult. There was no significant difference in rates of recurrence between perforator and FR flaps in our study, which wascomparable to other studies.12,15-17

Conclusion

References

1. Ramirez CC, Federman DG, Kirsner RS. Skin cancer as an occupational disease: the effect of ultraviolet and other forms of radiation. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:95---100.

2. de Vries E, de Poll-Franse LV, Louwman WJ, de Gruijl FR, Coebergh JW. Predictions of skin cancer incidence in the Netherlands up to 2015.Brit J Dermatol. 2005;152: 481---8. 3. Kwa RE, Campana K, Moy RL. Biology of mortality, liability. Prevention, treatment require planning, team work. J Ark Med Soc 2003;100:160-1.

6. Dharmarajan TS, Ahmed S. The growing problem of pressure ulcers.Evaluation and management for an aging population. Postgrad Med 2003;113:77-8. 81-84, 88-90. 7. Ger R. The surgical management of decubitus

ulcers by muscle transposition. Surgery 1971;69:106-10.

8. Minami RT, Mills R, Pardoe R. Gluteus maximusmyocutaneous flaps for repair of pressure sores. PlastReconstrSurg 1977;60: 242-9.

9. Yamamoto Y, Ohura T, Shintomi Y, et al. Superiority of the fasciocutaneous flap in reconstruction of sacral pressure sores. Ann PlastSurg 1993;30:116-21.

10. Yamamoto Y, Tsutsumida A, Murazumi M, et al. Longterm outcome of pressure sores treated with flap coverage. PlastReconstrSurg 1997;100:1212-7.

11. Yang CH, Kuo YR, Jeng SF, et al. An ideal method for pressure sore reconstruction: a freestyle perforator-based flap. Ann PlastSurg 2011;66:179-84.

12. Nola GT, Vistnes LM. Differential response of skin and muscle in the experimental production of pressure sores. PlastReconstrSurg 1980;66:728-33.

13. Koshima I, Moriguchi T, Soeda S, et al. The gluteal perforator based flap for repair of sacral pressure sores. PlastReconstrSurg 1993;91:678-83.

14. Sameem M, Au M, Wood T, et al. A systematic review of complication and recurrence rates of musculocutaneous, fasciocutaneous, and perforator-based flaps for treatment of pressure sores. PlastReconstrSurg 2012;130:67-77.

15. Baek SM, Williams GD, McElhinney AJ, et al. The gluteus maximusmyocutaneous flap in the management of pressure sores. Ann PlastSurg 1980;5:471-6.

16. Stevenson TR, Pollock RA, Rohrich RJ, et al. The gluteus maximusmusculocutaneous island flap: refinements in design and application. PlastReconstrSurg 1987;79:761e8.