Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 17 January 2016, At: 23:49

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Unlocking the transformative potential of

branchless banking in Indonesia

Tim Stapleton

To cite this article: Tim Stapleton (2013) Unlocking the transformative potential of branchless banking in Indonesia, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 49:3, 355-380, DOI:

10.1080/00074918.2013.850633

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2013.850633

Published online: 05 Dec 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 254

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/13/030355-26 © 2013 Indonesia Project ANU http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2013.850633

* Tim Stapleton is an Asian Century Graduate Fellow at the Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University. An earlier version of this article was submit-ted to the Institute of Public Affairs, London School of Economics and Political Science, in fulillment of the requirements of the master of public administration.

UNLOCKING THE TRANSFORMATIVE POTENTIAL OF

BRANCHLESS BANKING IN INDONESIA

Tim Stapleton*

Branchless banking has the potential to signiicantly enhance inancial inclusion among Indonesia’s large and geographically disparate unbanked population and to connect Indonesia’s micro, small and medium enterprises to the global economy. Why has the branchless-banking revolution not yet materialised? Constrained by regulation, deployments have failed to attract a critical mass of users. Indonesia’s fragmented telecommunications sector has made it dificult for providers to emu-late the success stories in other countries, in which dominant providers are com-peting for the market with a proprietary platform. In Indonesia, it is likely that a considerable degree of interoperability will be required for providers to unleash network effects and attract users. Indonesia’s providers are experimenting in this space. Recognising branchless banking’s potential to accelerate inancial inclusion, Bank Indonesia appears committed to improving the regulatory framework. This article identiies the components of an enabling regulatory environment. Success in Indonesia would provide a model for a more widespread uptake of transformative branchless banking.

Keywords: inancial inclusion, branchless banking, mobile money, network effects

INTRODUCTION

In Indonesia and other emerging economies, a large proportion of poor house-holds and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are excluded from

formal banking and lending services. Requiring small and infrequent inancial transactions, the poor are not proitable customers for the branch-led models of inancial service provision that predominate. By eliminating the need for costly

branch infrastructure, branchless banking can make serving poor, unbanked

households and MSMEs proitable. Branchless banking has the potential to revo

-lutionise payment systems in emerging markets, to extend formal inancial ser -vices to the unbanked and to provide a platform to connect MSMEs to the global economy.

Yet despite a proliferation of providers in recent years, branchless-banking deployments that are set to deliver this potential are the exception rather than the rule. Indonesia is a case in point. As a review of the branchless-banking landscape in the subsequent section highlights, Indonesia’s deployments have not achieved

critical mass. Yet branchless banking should ind a natural home in Indonesia,

whose citizens are enthusiastic adopters of new technologies and platforms: Indonesia boasts the fourth highest number of Facebook subscribers (Internet World Stats 2013), and in terms of the number of tweets Jakarta is the world’s most active city on Twitter, with Bandung also in the top 10 (Semiocast 2012).

Indonesia faces similar inancial-inclusion problems as countries where deploy

-ments have lourished, such as the Philippines and Kenya. Indonesia’s unbanked

are concentrated in rural areas across the archipelago, often beyond the reach of

banks’ limited branch networks or simply not a proitable proposition (or both). An estimated 100 million Indonesians do not have access to any inancial services

(CGAP 2013).

The Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) coined the term branchless banking to encompass the range of ‘new distribution channels that allow inan

-cial institutions and other commer-cial actors to offer inan-cial services outside traditional bank premises’ (Lyman, Gautam and Staschen 2006). Porteous (2006)

distinguished between transformative branchless-banking models, through

which providers seek to extend inancial services to unbanked and underbanked

individuals and MSMEs, and additive deployments, which merely provide an additional channel for banked customers or existing mobile-account holders to transact.

This article analyses existing barriers to – and the potential for – the rapid uptake of transformative branchless banking in Indonesia. Mas (2012: 292)

identi-ied four criteria for branchless banking to be transformative: in essence, these are

security, need, access and choice. The security criterion – that the funds of indi-viduals and businesses must be held securely – applies to deposit-taking entities worldwide, and branchless-banking providers and regulators in other markets have established mechanisms to meet this. Any attempt to meet the remaining criteria should consider the characteristics of the Indonesian market.

The need criterion – whether branchless-banking schemes can provide a range

of hitherto unavailable inancial services to meet the inancial needs of unbanked

individuals and MSMEs – can be thought of as the demand side of the equation. The third section of this article considers whether a lack of demand for branchless

banking in Indonesia has hindered its uptake, and identiies potential sources

of demand. The access and choice criteria relate to the supply side of branch-less banking. The access criterion requires that the infrastructure exists, or can be developed, to make affordable branchless-banking services available near where unbanked individuals live and MSMEs operate. Choice requires that there be a fair and contestable market that both maximises network effects for consumers and protects against abuses of potential dominant market positions. The fourth section considers whether supply-side barriers have discouraged – and will pre-clude – the widespread uptake of transformational branchless banking in Indo-nesia.

As a platform-mediated, two-sided market subject to strong network effects (Anderson 2010), in which banking, telecommunications or other entities (or a

combination thereof) provide a platform for the provision of inancial services

to the poor, transformative branchless banking straddles several sectors that are typically highly regulated. Branchless-banking deployments, be they transforma-tive or additransforma-tive, have tended to achieve critical mass in environments in which

regulation is either (a) effectively absent or (b) incremental and proportional, and underpinned by an active and ongoing dialogue between industry and regulators. In other regulatory environments, deployments have struggled to achieve scale. In the Indonesian context, Hidayati (2011) argued, regulations prohibiting banks and mobile operators from building cash-merchant networks have precluded deployments from achieving critical mass.

The regulator, Bank Indonesia (BI), is attuned to the potential of branchless

bank-ing to accelerate inancial inclusion. BI’s pilot of branchless bankbank-ing in selected

provinces in Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan and Sulawesi from May to November 2013 is a precursor to a branchless-banking regulation. It is therefore timely to examine the extent to which Indonesia’s regulatory settings have frustrated the widespread uptake of branchless banking, and to identify the components of an enabling regulatory environment – drawing on the regulatory approaches used in

more established markets. This is the focus of the ifth section.

Why has transformative branchless banking lourished in the Philippines yet loundered in Indonesia? This article inds that a range of restrictions in Indone -sia’s regulatory environment have, until recently, precluded branchless-banking

providers from serving the considerable unmet demand for inancial services

among Indonesia’s unbanked households and MSMEs. And while there is no

shortage of potential delivery partners and channels, the path to building a proit

-able branchless-banking deployment appears more dificult in Indonesia than in

established markets such as the Philippines and Kenya, where one or two large mobile-network operators (MNOs) have used their dominant positions in mobile telephony to attract a critical mass of users to their incompatible, proprietary branchless-banking platforms. In Indonesia, the commercial banking sector’s narrow focus on corporate lending, the relatively fragmented and competitive telecommunications market, the limited reach of alternative networks, and the

potential signiicance of inward international remittances, government cash trans -fers and m-commerce in early market-building mean that the platforms of

provid-ers will need to be interconnected to generate network beneits and attract usprovid-ers.

If Indonesia’s regulatory and policy settings were to become more conducive to the widespread uptake of transformative branchless banking – and if providers

could generate network beneits through interoperability, as the country’s three

largest MNOs are attempting to do – Indonesia could yet become an exemplar for emerging economies.

BRANCHLESS-BANKING MODELS AND THE INDONESIAN LANDSCAPE

Notwithstanding its promise to enhance inancial inclusion, transformative

branchless banking remains a nascent industry. As of February 2013, of the 150

live deployments around the globe (identiied by the GSM Association’s Mobile

Money for the Unbanked program) only six had more than 1 million active cus-tomers and only 14 had achieved rapid growth (Pénicaud 2013). Most, including those in Indonesia, remain in a subscale position.

Branchless-banking deployments are typically led by MNOs, banks or, increas-ingly, third-party providers – or a combination of these entities. Often referred to as ‘mobile money’ or ‘mobile banking’, MNO-led deployments rely on mobile-telephony infrastructure as the channel and mobile phones as the interface to

enable transfers of e-money, an electronic store of value. Measured by the num-ber of registered users, MNO-led deployments predominate in Indonesia. As of May 2013, Indonesia’s MNO-led mobile-money services had 12 million reg-istered users – approximately 4.3% of mobile subscriptions – and two million agents,1 with Telkomsel accounting for the most users.2 Yet only a small minority

of users are thought to be active, and the services are primarily used for airtime top-ups (Jakarta Post, 27/2/2012). At present, Indonesia’s MNO-led deployments are primarily additive, extending a convenience to existing users in a bid to retain customers.

In MNO-led deployments, users’ e-money wallets may or may not be linked to

individual bank accounts. Like Philippine provider Globe’s GCASH and Kenyan

operator Safaricom’s M-PESA service, the e-money deployments of Indonesia’s

three largest MNOs – Telkomsel’s T-Cash, Indosat’s Dompektu and XL’s Tunai

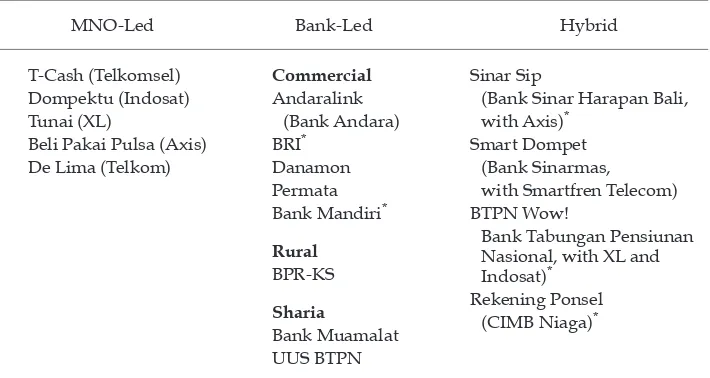

(table 1) – do not offer users individual bank accounts. In contrast, the pioneer-ing branchless-bankpioneer-ing deployment – Philippine provider Smart Communica-tions’ SMART Money – links customers’ e-money wallets to individual bank accounts. In Indonesia and in most other markets, branchless-banking providers are required by regulation to maintain a pooled bank account with a cash balance equivalent to the aggregate value of e-money on issue.

Regulators in several of Asia’s new high-growth branchless-banking markets, such as Pakistan and Bangladesh, require branchless-banking deployments to be bank-led or bank-centric. BI prefers – but does not mandate – bank-centric deployments, on the grounds that extending individual bank accounts to the

unbanked will be more inancially inclusive (enabling the poor to develop inan -cial histories), underpin stronger economic growth (by stimulating lending) and afford greater consumer protections (by virtue of a robust regulatory environ-ment for banks and deposit insurance)3. BI’s Real Time Gross Settlement system

for transactions affords bank-centric models greater utility than in countries in which interbank transactions are still processed manually. Several commercial and regional Indonesian banks have launched transformative branchless-banking deployments, relying on mobile bank staff equipped with electronic-data-capture

(EDC) machines (table 1). Yet such deployments are signiicantly smaller in scale

than those of Indonesia’s MNOs: in conjunction with MNO Axis, Bank Mandiri subsidiary Bank Sinar Harapan Bali extended accounts to 2,500 unbanked cus-tomers by the end of 2012 under its Sinar Sip trial of branchless banking in Bali, Sinar Sip (Bank Mandiri 2013).

Proponents of branchless banking see it enabling a cashless society. While e-money is increasingly being accepted as a payment method in Indonesia, for the foreseeable future branchless-banking deployments will require a supporting

1 Correspondence with BI oficials, May 2013. There were more than 278 million mobile subscriptions in Indonesia at the end of 2012 (GSMA 2013).

2 According to a Telkomsel spokesperson, T-Cash and the Tap-Izy payments facility had 8 million customers combined as of February 2012 and were targeting 10 million by the end of that year (Jakarta Post, 27/2/2012).

3 Discussions with BI oficials, May 2013.

network of cash merchants4 to exchange cash to and from e-money.

Regula-tions permitting, cash merchants can be individuals or entities with a presence in unbanked communities and may serve unregistered customers, obviating the

need for customers to have a mobile phone or a bank account. Leading deploy -ments in the Philippines (Globe GCASH and Smart Money), Cambodia (WING) and Pakistan (Easy Paisa) have recorded strong growth by offering, through their cash merchants, over-the-counter (OTC) transactions to unregistered customers for person-to-person transfers (P2P), bill payments (P2B) and government pay-ments (G2P) (Owens 2013). The term ‘branchless banking’ is something of a mis-nomer: cash merchants operate ‘beyond-bank branches’, which are still required to support the liquidity of the cash-in, cash-out network (Alexandre, Mas and Radcliffe 2011).

Branchless-banking providers tend to use per-transaction pricing, charging both sender and receiver for transfers and for cash in or out (often for the cost of a text message or for a portion of the amount transferred). Yet in platform-mediated, two-sided markets such as branchless banking, providers can generate income from either or both sides of the network, allowing for an array of pricing strategies, including subsidising one group of users to attract another. To promote branchless banking and to allow MNOs to scale beyond the domestic transfer mar-ket, CGAP advocates for providers to adopt a ’freemium’ model, which captures revenues from major customers and businesses who use premium services, such

4 Cash-in, cash-out agent is the more established term in the literature. Yet the relation is more akin to reselling than agency, since cash-in, cash-out transactions are typically funded from cash merchants’ own accounts, (Alexandre, Mas and Radcliffe 2011; Dermish et al. 2012).

TABLE 1 Branchless-Banking Services in Indonesia

MNO-Led Bank-Led Hybrid

(Bank Sinar Harapan Bali, with Axis)*

Smart Dompet (Bank Sinarmas, with Smartfren Telecom) BTPN Wow!

Bank Tabungan Pensiunan Nasional, with XL and Indosat)*

Rekening Ponsel (CIMB Niaga)*

Sources: Satria (2013); providers’ websites; Jakarta Post (4/9/2013, 5/10/2013)

Note: MNO = mobile-network operator.

* Bank participating in Bank Indonesia’s branchless-banking pilot.

as bulk payments, and allows individuals and MSMEs to transact for free below established limits (Kumar and Mino 2011). A ‘freemium’ provider in Somaliland, for example, has generated large transaction volumes: 8.3 million transactions from 250,000 customers in June 2012.5 ‘Freemium’ is an example of a new, proit

-able pricing strategy that would be attractive to poor households, which transact less frequently and with lower amounts.

IS BRANCHLESS BANKING INHIBITED BY A LACK OF DEMAND?

Branchless-banking deployments aim to generate high transaction volumes to

achieve proitability. Is it conceivable that a lack of demand for formal inancial

services among Indonesia’s unbanked and underbanked populations has pre-cluded branchless-banking deployments from achieving scale? With an estimated

100 million Indonesians lacking access to inancial services of any kind and only 19.6% of Indonesia’s 247 million citizens holding an account at a formal inan -cial institution (World Bank Finan-cial Index 2011), this seems unlikely. Having conducted focus-group discussions in various regions of the archipelago, the

IFC (2010) identiied strong demand for branchless P2B and P2P transactions. Branchless-banking deployments in other countries have generated proitable

transaction volumes by providing these services.

Branchless-banking deployments often initially bypass the poorest segments of the population. Network effects in branchless banking dictate that providers

compete iercely to win over pivotal ‘early adopters’ (Farrell 2008: 3), who – with greater inancial resources – will transact more regularly and, in led or

bank-centric deployments, maintain higher deposits than the poorest unbanked. They will also attract subsequent adopters, who are more likely to join the network with the most users.

Following interviews with new and potential providers of branchless-banking services in Indonesia, the IFC (2010) concluded that such providers would initially target Indonesia’s large middle layer of ‘relatively underbanked’ households – income-earning households that are not wealthy but have spendable income – as well as the borderline underbanked and banked segments above and below those

households. While still important, the inancial needs of early adopters are likely

to be less pressing than those from the poorest segments of the population.

Unlocking additional transaction volumes

Beyond P2B and P2P, this article identiies three potential sources of demand for

branchless banking in Indonesia: G2P, MSME transactions and inward interna-tional remittances. With the appropriate policy and regulatory framework in place, these sources could yet unlock substantial transaction volumes in branchless bank-ing and encourage providers to extend services to Indonesia’s poorest unbanked.

Government payments

In 2011–12, the Philippine government used Globe’s GCASH service to transfer more than $100 million in conditional cash transfers to recipients who did not own mobile phones (Owen 2013). In contrast, the Indonesian government relies

5 Discussions with Kabir Kumar, CGAP, 24 April 2013.

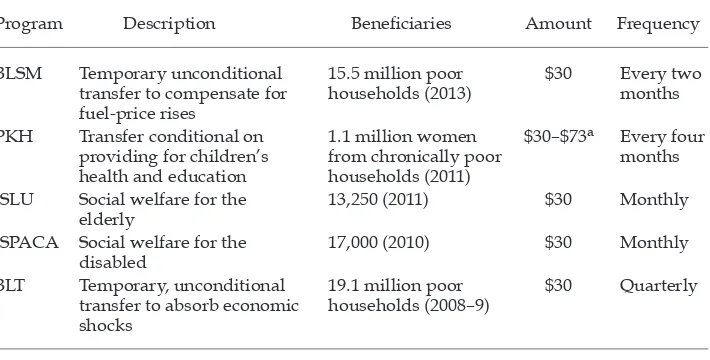

on PT Pos’s extensive agent network to distribute cash transfers to poor house-holds (table 2).

Administrative costs for two of the largest schemes – BLT and PKH – were

approximately 8% and 18% of the program budgets (Febriany and Suryahadi

2012). As a recent TNP2K (2012) report identiied, branchless-banking schemes

have the potential both to lower the cost and to increase the speed, security, fre-quency and convenience of these G2P transfers. Some of the resulting savings could be used for smaller, more frequent transfers to poor households, thereby aiding households’ budgeting. There may also be scope for a more wholesale government adoption of branchless banking as a distribution and revenue collec-tion channel for unbanked segments of the populacollec-tion. With providers likely to focus on securing transaction volumes (section 3), government ministries’ early adoption of branchless banking would accelerate deployments in areas where the unbanked are concentrated.

Branchless-banking deployments have been used to expedite the delivery of cash assistance in the aftermath of humanitarian crises, including in Haiti, Kenya and Nepal. This potential could be factored into emergency response planning in Indonesia. If vendors in areas affected by natural disasters do not widely accept e-money as a payment method, arrangements to deploy additional cash mer-chants and replenish the liquidity of cash mermer-chants on the ground would be required.

Platform for MSMEs

MSMEs are a vital component of Indonesia’s economy: in 2009, they contributed 56.5% of Indonesia’s GDP and accounted for 97% of employment – much higher

than in neighbouring countries (Shinozaki 2012: 2). Yet access to formal inance is TABLE 2 Temporary and Ongoing Indonesian Government Cash-Transfer Programs

Program Description Beneiciaries Amount Frequency

PKH Transfer conditional on providing for children’s

JSLU Social welfare for the elderly

13,250 (2011) $30 Monthly

JSPACA Social welfare for the disabled

Sources: Febriany et al. (2012: 3–4); Kharisma (2008: 6–7); World Bank (2012)

Note: BLSM = Bantuan Langsung Sementara Masyarakat. PKH = Program Keluarga Harapan.

JSLU = Jaminan Sosial Lanjut Usia. JSPACA = Jaminan Sosial Penyandang Cacat. BLT = Bantuan Langsung Tunai.

a Figures from 2007. The amount depends on household characteristics.

acutely limited: 2010 survey data suggest that just over half obtain inance from

banks, while more than a quarter rely on funding from relatives and friends (Shi-nozaki 2012: 12–14). The outstanding value of loans to SMEs accounted for just 0.7% of GDP in 2010, compared with 17.4% in Malaysia and 30.7% in Thailand (CGAP 2010a). Though total credit has been growing at an annual rate of nearly 20%, the loan portfolios of Indonesia’s largest banks have been dominated by loans to large corporates and the bulk of credit reported as micro, small and medium loans is for consumption, rather than for supporting the operations of MSMEs (Prasetyantoko and Rosengard 2011: 281–2). Branchless banking affords Indonesia’s banks an opportunity to meet the lending targets for

government-guaranteed micro loans to MSMEs, and thereby to reduce the large MSME inanc -ing gap.

Branchless banking could serve as a platform on which this large sector could transact and innovate. Nairobi, for example, has emerged as a technology hub, with entrepreneurial Kenyan start-ups developing mobile applications built on Safaricom’s dominant M-PESA platform, such as electronic versions of informal savings groups and M-Farm, which provides agricultural-market prices and allows farmers to group together to buy and sell products (Economist, 25/8/2012).

Delivering inancial and other services via large-scale branchless-banking

deployments can broaden uptake and increase transaction volumes, owing to their cost-effectiveness and their having a wider footprint than traditional deliv-ery models. In the absence of a dominant branchless-banking deployment,

cap-turing these indirect network beneits in Indonesia would require interoperability

between providers, which is a focus of section 4.

Inward international remittances

By driving down the costs of, and increasing the competition for, inward inter-national remittances of Indonesia’s estimated 6.8 million migrant workers (World Bank 2008: xiii, 2013), innovative branchless-banking deployments could

yield signiicant gains for development in Indonesia. Yang (2008) showed that

remittance-receiving migrant households in the Philippines invested increased remittance income in child education and new enterprises.

Indonesia’s GDP is less dependent than that of other emerging economies on remittances from documented migrant workers through formal channels. According to the latest World Bank calculations, remittances contribute approxi-mately 1% of Indonesia’s GDP, roughly comparable to their share in China but lower than that in India (3%), the Philippines (10%), Bangladesh (11%) and

sev-eral South Paciic nations (table 3). Remittances to Indonesia are concentrated in

a few rural provinces, where the families of the majority of Indonesia’s migrant workers reside. These provinces are among the poorest in Indonesia (World Bank

2008: 8–9). Formal remittance inlows far exceed regional government budgets

in several of these, including East Java, East Flores (Hugo 2007) and West Nusa Tenggara (World Bank 2008). In the East Javanese regencies of Malang, Tulun-gagung and Blitar, inward remittances accounted for 42%, 23% and 13% of local economic output in 2004 (Barnes 2007: 61), suggesting that within these provinces branchless-banking providers may be able to direct initial deployments to areas with the highest potential transaction volumes. The actual amount remitted is estimated to be three times greater than is formally recorded (World Bank 2008:

11), because large amounts are sent informally through returnees (Hugo 2007; IFC 2010:10) and an estimated 4.3 million Indonesian workers are undocumented (World Bank 2008: xiii).

The contribution of remittances to gross regional domestic product (GRDP) in the provinces in which the families of Indonesia’s migrant workers reside is

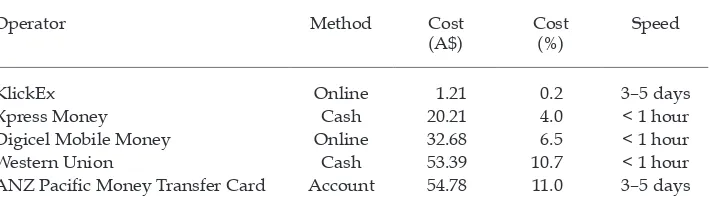

on a scale comparable to that of South Paciic nations (table 3). The innovative

branchless-banking deployments of Digicel Mobile Money and KlickEx (and

subsequently Vodafone M-PAISA) on the Australasia–Paciic Islands remittance

corridor6 have increased competition and reduced international remittance costs

(table 4; Dalberg 2012: 34, 47). These deployments take advantage of KlickEx’s innovative, low-cost P2P service, which minimises foreign-exchange costs by matching individual senders of funds. Other innovations – including the devel-opment of hubs that promote interoperability between partners on the sending and receiving sides (such as that of BICS Home Send) – offer the potential to lower the cost and time-to-market of branchless-banking deployments on international remittance corridors, relative to the traditional approaches of negotiating bilateral partnership agreements with individual MNOs (as Globe did for GCASH) or rely-ing on Western Union in the sendrely-ing countries (as Safaricom does for M-PESA).

Indonesia’s migrant workers are concentrated in relatively few markets else-where in Asia and in the Middle East: more than half are in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia (Asia News Network, 30/4/2013; Hugo 2007). Recognising the potential for

international remittances to unlock transaction volumes on signiicant remittance corridors (Davidson and Leishmann 2012: 22), Indonesian MNOs XL and Telkom

have enabled inward remittances from Malaysia and Hong Kong, respectively,

6 Digicel launched Digicel Mobile Money in Fiji, Samoa and Tonga to facilitate inward remittances from Australia and New Zealand. The funds can be used for onward transfers, purchases, bill payments and airtime top-ups. Digicel partnered with KlickEx to offer a much cheaper service than their competitors. Following Digicel’s entry, ANZ lowered its transfer fee from A$32 to A$8, and Western Union offered discounts on transfer fees. Voda-fone M-PAISA’s subsequent entry into the Fijian market has added to ierce competition (Dalberg 2012).

TABLE 3 International Remittances in Selected South Paciic Countries and

Indonesian Provinces

South Paciic Countries, 2012 Indonesian Provinces, 2010

Country % of GDP Province % of GRDP

Samoa 21 West Nusa Tenggara 13

Tonga 16 West Java 3

Fiji 4 East Nusa Tenggara 3

Sources: BNP2TKI (2011) for remittance data for Indonesian provinces; World Bank (2013) for South

Paciic countries.

Note: GRDP = gross regional domestic product.

through their mobile-money networks.7 The breakdown of foreign ownership

in Indonesia’s three largest MNOs should encourage further deployments in Indonesia’s major inward remittance corridors: Telkomsel is part-owned by

Singapore’s Singtel, XL is a member of Malaysia’s Axiata group, and IndoSat is

majority owned by Qatar’s Qtel, which operates across much of the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia.

Studies of the potential for international remittances through branchless banking have concluded that providers should focus on developing domestic ecosystems – such as widespread cash-merchant networks that support the use of mobile wallets for domestic bill payments and transfers – before deploying international remittance programs. Recipients value being able to undertake these downstream transactions (Dalberg 2012: 4; Bangladesh Bank 2012: 11), which

inluences a remitter’s choice of platform. However, the above factors suggest that

international remittances may be a considerable source of demand for branchless banking and an effective early market-building strategy in Indonesia.

SUPPLY-SIDE CONSTRAINTS?

In Kenya and the Philippines, which are at the vanguard of transformative branchless banking, MNOs have used their dominant positions and sizeable mar-ket shares in mobile telephony to deploy sizeable cash-merchant networks and thereby attract many new customers to their proprietary branchless-banking plat-forms. Vodafone’s Safaricom is the dominant MNO in Kenya, holding an 88% share of the mobile-telephony market in 2011. In branchless banking, users value compatibility: the more transacting parties on a network, the greater its value to existing and prospective users. These strong network effects draw users to the

platform that offers – or is expected to offer – the greatest network beneits. Safari -com’s large number of mobile-telephony customers gave it a particular advantage

7 XL Tunai subscribers can receive remittances from Malaysia through Celcom AirCash. In October 2011, Telkom Indonesia subsidiary Telekomunikasi Indonesia (Telin) Interna-tional (Hong Kong) Limited launched a prepaid SIM card designed for Indonesian migrant workers that enables remittances to family and friends on the Telkomsel, Flexi, Indosat and XL networks (Telin 2011). Telkomsel offers a two-in-one prepaid SIM card (with both a Hong Kong and an Indonesian number) that supports international remittances to Indone-sian mobile-money or bank accounts (Telkomsel 2013).

TABLE 4 Cost of Remitting A$500 from Australia to Tonga, Selected Operators

(10 September 2013)

Operator Method Cost

(A$)

Cost (%)

Speed

KlickEx Online 1.21 0.2 3–5 days

Xpress Money Cash 20.21 4.0 < 1 hour

Digicel Mobile Money Online 32.68 6.5 < 1 hour Western Union Cash 53.39 10.7 < 1 hour ANZ Paciic Money Transfer Card Account 54.78 11.0 3–5 days

Source: Sendmoneypaciic.org

in attracting a critical mass of users to its branchless banking platform.8 Relect

-ing on the Kenyan experience, Klein and Mayer (2011) argued that branchless-banking networks are, to some degree, natural monopolies.

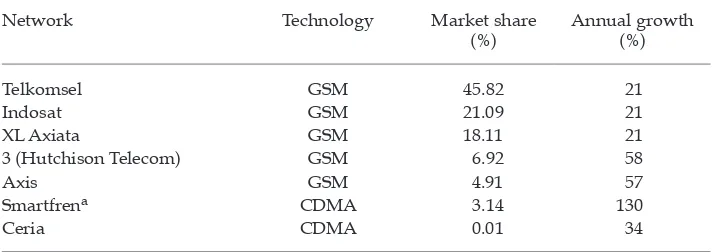

Indonesia’s telecommunications market is more fragmented than Kenya’s. While Telkomsel is the clear market leader (table 5), it has ceded considerable market share since its parent, Telkom Indonesia, lost its monopoly during deregulation in 1999. And though the three largest GSM-based networks account for 85% of mobile connections, there is stiff price competition to attract users, and the smaller MNOs are recording the strongest growth (table 5).

Nor can any inancial institution claim a dominant market position in Indo -nesia’s banking sector: no single bank has a market share greater than 15%, and only three banks have a market share greater than 10% (Prasetyantoko and Rosengard 2011: 286). Yet in contrast to deregulation and price competition in the telecommunications sector, the Arsitektur Perbankan Indonesia (Indonesia Bank-ing Architecture, API) program, which BI instituted to prevent a repeat of the 1997 Krismon banking meltdown, has helped to consolidate Indonesia’s banking

sector: the ive largest banks hold approximately half of the system’s total assets,

credit outstanding and third-party funds.

Has the competitive structure of the telecommunications and banking sectors precluded branchless banking from achieving critical mass in Indonesia? Is devel-oping the transaction infrastructure and distribution channels that are essential for the viability of branchless-banking deployments an insurmountable task?

8 Klein and Mayer (2011) questioned whether Safaricom would have entered the branchless-banking market and developed its M-PESA platform without the prospect of recouping substantial investments by securing market dominance with an incompatible, proprietary platform.

TABLE 5 Market Share and Growth of Indonesia’s GSM and CDMA Mobile Operators (by number of connections, Q1 2011)

Network Technology Market share (%)

Annual growth (%)

Telkomsel GSM 45.82 21

Indosat GSM 21.09 21

XL Axiata GSM 18.11 21

3 (Hutchison Telecom) GSM 6.92 58

Axis GSM 4.91 57

Smartfrena CDMA 3.14 130

Ceria CDMA 0.01 34

Source: Wireless Intelligence (2011).

Note: Excludes CDMA ixed-wireless and WiMAX operators. CDMA ixed-wireless players Telkom -Flexi and Bakrie Telecom had approximately 25 million connections between them as of Q1 2011 (Wireless Intelligence 2011).

a Merger of Smart Telecom and Mobile-8 (Wireless Intelligence 2011).

Competitive structure and network effects

BI’s approach to regulatory and monetary policy since Krismon appears to have fostered a banking sector that has largely ignored Indonesia’s unbanked popula-tion and MSMEs. The genesis of the API program was BI’s belief that a small, administratively determined number of large, full-service commercial banks would be safer than a broader and more diverse banking sector generated by mar-ket forces. API unintentionally created barriers to entry and exit in the sector: for one, it is virtually impossible to establish a new bank in Indonesia without buying an existing bank’s licence (Prasetyantoko and Rosengard 2011: 288–9). Foreign-ownership restrictions introduced in 2012 are likely to have further entrenched existing players. Johnston et al. (2007) argued that the treatment of Indonesia’s

microinance institutions as small commercial banks under API – including sub -jecting them to the same high minimum-capital requirements – has discouraged innovation and outreach at the micro-banking level. Partly in response to BI’s reli-ance on reserve requirements and the issureli-ance of short-term promissory notes to

control inlation, the commercial banking sector now generates most of its income

from interest on loans to large corporates and on investments in central bank and government securities (Prasetyantoko and Rosengard 2011: 281–2).

Prasetyantoko and Rosengard (2011) argued that these policies have fostered

a highly liquid, solvent and proitable yet ineficient and narrowly focused

rent-seeking oligopoly. Until recently, the sector has generated extremely high price-to-earnings ratios, average operating ratios and net interest margins (the margin between lending and deposit rates), yet MSMEs have been unable to obtain credit. Given these constraints, the willingness of several Indonesian banks to participate in BI’s branchless-banking pilot is encouraging. With Indonesia’s current economic wobbles expected to increase the number of non-performing loans and undermine returns in the sector (Economist, 14/9/2013), low-cost branchless-banking

deploy-ments give banks the opportunity to develop proitable new revenue streams.

The economics of network effects, in theory, at least, does not preclude branchless-banking deployments from achieving critical mass in more fragmented and competitive telecommunications and banking markets. In the absence of regulation mandating interoperability, branchless-banking providers are free to

maximise their long-term proits from network beneits (Bellis and Houpis 2007:

37) in one of two ways: (a) by competing for the market, with an incompatible,

proprietary platform, thereby monopolising the network beneits; or (b) by com -peting in the market, with compatible deployments, thereby sharing a larger pool

of network beneits (Economides 2006; Farrell and Klemperer 2007).

A provider will probably be conident that it can dominate a scheme of domes -tic branchless-banking transfers and payments scheme if it has, among other things, a large installed or expected user base; a dominant actual or expected posi-tion in a complementary market (whether in mobile telephony, banking or retail

distribution); superior product or reputation; irst-mover advantage; or a cost

advantage over its rivals (Bellis and Houpis 2007: 38; CGAP 2011). Such providers typically invest heavily in platform development, penetration pricing, marketing and a critical scale of cash-merchant networks (Klein and Mayer 2011), in order to secure ex-post dominance and monopoly rents (Farrell and Klemperer 2007). Each of the major branchless-banking deployments that have achieved critical mass to date has pursued a similar strategy: most deployments eschew interoperability,

permitting only on-network transfers; others permit limited forms of interconnec-tion through off-network transfers (table 6).

Though not yet prevalent in branchless banking, interoperability should enable

providers to overcome frictions and capture higher levels of network beneits if:

• complementary markets (such as mobile telephony) are more competitive and fragmented;

• their deployments are at a similar stage, with none expected to achieve dominance;

• indirect network effects arise in related markets (Klemperer 2008);

• it allows irms to overcome stagnant growth or enter new markets (CGAP 2011);

• it catalyses growth in markets that use branchless banking as a platform,

unlocking signiicant additional transaction volumes; or

• the providers are smaller players seeking to compete with a larger proprietary platform.

Dominance of the telecommunications and banking sectors by one or two provid-ers is therefore not a prerequisite for branchless-banking deployments to offer the

network beneits and thereby attract the critical mass of users necessary for proit -ability. Yet nor is there a clear path to a viable, interoperable branchless-banking market – for at least two reasons. First, despite there being various levels at which branchless-banking services could interoperate or interconnect (table 7), interop-erability success stories are rare. Providers in fragmented markets therefore lack

models to emulate. Second, banks and MNOs have found it dificult to develop mutually proitable models in Bangladesh and in other markets where regulators

prefer bank-led models (Bangladesh Bank 2012: 14). MNOs and banks pursue dif-ferent business models: telecommunications is transaction-based while banking is

loat-based (Donovan 2012: 65). Bangladesh Bank adopted an ‘honest broker’ role

to bridge differences between BRAC Bank and Dutch-Bangla and Bangladeshi MNOs, thereby enabling the rapid growth of Bangladesh’s two largest deploy-ments (Bangladesh Bank 2012). Overall, however, these two reasons are likely to have hindered branchless-banking deployments from achieving critical mass in Indonesia and elsewhere.

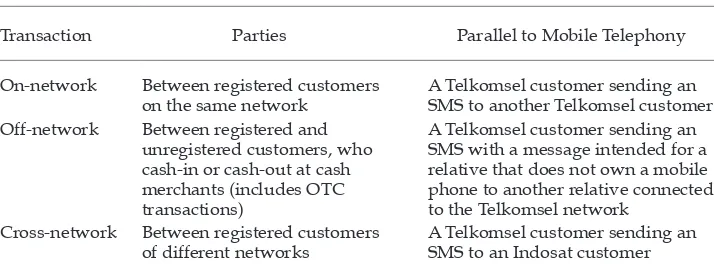

TABLE 6 Branchless-Banking Transactions

Transaction Parties Parallel to Mobile Telephony

On-network Between registered customers on the same network

A Telkomsel customer sending an SMS to another Telkomsel customer Off-network Between registered and

unregistered customers, who cash-in or cash-out at cash merchants (includes OTC transactions)

A Telkomsel customer sending an SMS with a message intended for a relative that does not own a mobile phone to another relative connected to the Telkomsel network

Cross-network Between registered customers of different networks

A Telkomsel customer sending an SMS to an Indosat customer

Note: SMS = Short Message Service. OTC = over the counter.

Indonesia is a potential bellwether of branchless-banking interoperability; on 15 May 2013, Indonesia’s three largest MNOs interconnected their mobile-money platforms for funds transfers. Interoperability should remove frictions in Indo-nesia’s telecommunications market, allowing MNOs to realise greater network

beneits. Indonesia’s payments system also provides interoperability between

bank-centric branchless-banking models.

By extending the availability and convenience of branchless-banking services in Indonesia, interoperability and interconnection have the potential to lower costs and increase transaction volumes for inward international remittances, for G2P payments to households in remote areas that are not served by more than one provider, for MSMEs transacting over branchless-banking networks,

and for inancial services and m-commerce applications. Full interoperability

between branchless-banking deployments could provide a common platform

for m-commerce to lourish in Indonesia, just as Safaricom’s dominant M-PESA

platform in Kenya and the Internet worldwide have kindled innovation without requiring complex negotiations or agreements with multiple platform sponsors (Economides 2006; Economist, 25/8/2012). An interoperable branchless-banking ecosystem would allow Indonesian developers and service providers to offer products that are better matched to customers’ needs.

Branchless infrastructure and channels in Indonesia

To succeed, branchless-banking deployments need transaction infrastructure (such as a mobile network); an interface (such as a mobile phone or an EDC machine) and distribution channels, including a network of cash-in, cash-out merchants (or mobile-bank staff); and supporting arrangements to replenish the liquidity of that network, through bank branches or similar. Indonesia’s bank-ing sector has limited reach. As of early 2013, commercial banks had just 14,820

TABLE 7 Possibilities for Interconnection in Branchless Banking

Platform interoperability Branchless-banking providers interconnect their platforms directly or indirectly through a third-party interface to enable cross-network transfers between their users at the domestic or international level.

Cash-merchant interoperability Cash merchants enable transfers between users of competing branchless-banking networks.

Customer-level interoperability Customers are not tied to a particular technology or network to access their e-money wallet

Interconnection to third-party platforms

Providers connect their platforms to those of inan-cial institutions or other payment networks to ena-ble transfers between customers’ e-money wallets and their bank (or other payment) accounts. Provision of a common

third-party interface

Proprietary branchless-banking services offer a single interface to third parties to simplify bulk and merchant payments.

Sources: Adapted from CGAP (2011); Davidson and Leishman (2012: 15–16); Kumar and Tarazi (2012a).

ofices concentrated in urban areas (Satria 2013), although this number has risen

steadily over time (Prasetyantoko and Rosengard 2011: 275). While the regional operations of Indonesia’s People’s Credit Banks (Bank Perkreditan Rakyat, BPRs)

should help them to enhance inancial inclusion among Indonesia’s rural poor,

in practice BPRs have limited access to Indonesia’s payments system and their operational remit is restricted to single provinces. With a limited branch footprint, banks will need to rely on the distribution channels of MNOs or third parties to achieve rapid uptake.

Mobile-network infrastructure reaches considerably further than banks into rural areas. Indonesia’s three largest MNOs have followed increased

mobile-telephony trafic to outlying rural areas, extending the capacity and reach of

their networks; and MNOs have been collaborating to expand their networks beyond Java, signing a series of infrastructure-sharing deals to recoup the costs of extending their coverage (IFC 2010: 8). Since the telecommunications sector was deregulated in 1999, Indonesia’s mobile-telephony market has grown to be the fourth largest in the world, by network connections. The number of mobile subscribers in Indonesia dwarfs the number of bank accounts: there were over 278 million mobile connections and 90.3 million unique mobile-phone subscribers as of the beginning of 2013 – a market penetration of 37% (Wireless Intelligence in GSMA/IFC 2013: 8–9). This suggests that approximately 40 million unbanked Indonesians own a mobile phone.

Yet branchless banking could bring inancial services to a much larger pro -portion of the unbanked population if, as in other markets, a network of cash merchants is permitted to conduct OTC transactions on behalf of unregistered users. Among the many candidates for cash-merchant networks, the state-owned

post ofice, PT Pos, is noteworthy. Its network of 4,000 ofices, 1,000 mobile point-of-service ‘stations’, 7,000 postal workers and 17,000 agencies (2010 igures)

reaches across the archipelago, and makes it a potentially attractive partner for branchless-banking deployments (IFC 2010:13). Bank Mandiri has signed a co-operation agreement with PT Pos to assist in the delivery of its

branchless-bank-ing program. The approximately 190,000 cooperatives and 600,000 microinance

institutions (Satria 2013) in Indonesia also have considerable potential.

Although it is dificult for any branchless-banking provider to develop the req -uisite platform, transaction and distribution infrastructure, the obstacles do not appear to be considerably greater in Indonesia than in other markets in which

branchless banking has lourished. The absence of a dominant player in Indone -sia’s telecommunications and banking sectors hampers – but does not preclude

– the ability of providers to capture network beneits with proprietary platforms.

This analysis suggests that interoperability in Indonesia may be a more viable proposition than in Kenya and the Philippines for providers seeking to make the

most of network beneits. Competition in the market may prevail over compe-tition for the market. Should transformative branchless-banking deployments interoperate and achieve scale, Indonesia could be a model for other emerging

economies in the Asia-Paciic region seeking to harness network beneits for inan -cial inclusion – even in the absence of a dominant player in telecommunications or banking.

THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT: ENABLING OR CONSTRAINING?

The preceding sections have identiied sources of demand for branchless banking

in Indonesia and established that the supply-side challenges are not insurmount-able. To what extent, then, have Indonesia’s regulatory settings frustrated the widespread adoption of branchless banking? In comparison to more established branchless-banking markets, what elements of an enabling regulatory environ-ment are missing in Indonesia?

Prominent among the objectives of central banks, which typically regulate

branchless-banking platforms, is safeguarding the stability of the inancial sys -tem. Disruptive technologies and new business models challenge regulators’ ability to understand the potential risks of branchless banking. This points to the need for caution. Yet branchless-banking platforms have tended to achieve critical mass in environments in which regulation is either absent or incremental and pro-portional, and underpinned by an active and ongoing dialogue between indus-try and regulators. Kimenyi and Ndung’u (2009) argued that regulators need to strike a balance between system stability and access to services. While regula-tory regimes have yet to be tested by the failure of a large branchless-banking scheme (Dermish et al. 2012: 91), several reviews have concluded that the risks are primarily operational and can be managed by applying prudent systems and controls to real-time transaction monitoring (Alexandre, Mas and Radcliffe 2011;

Lyman, Gautam and Staschen 2008).

BI has adopted a more cautious approach. It has long permitted banks and non-banks to issue e-money, and it granted formal regulatory approval in 2009,9 but it

had until recently been reluctant to remove a number of regulatory impediments to branchless banking. Its issuing an updated funds-transfer regulation in Decem-ber 201210 and new guidelines for a branchless-banking pilot (BI 2013: attachment

A) in April 2013 relected its desire to have branchless banking enhance inancial

inclusion. From May to November 2013, approved Indonesian banks and MNOs

piloted ‘limited payment and banking systems service activities through inancial service intermediary units’ (UPLKs) in the subdistricts of North Sumatra, South

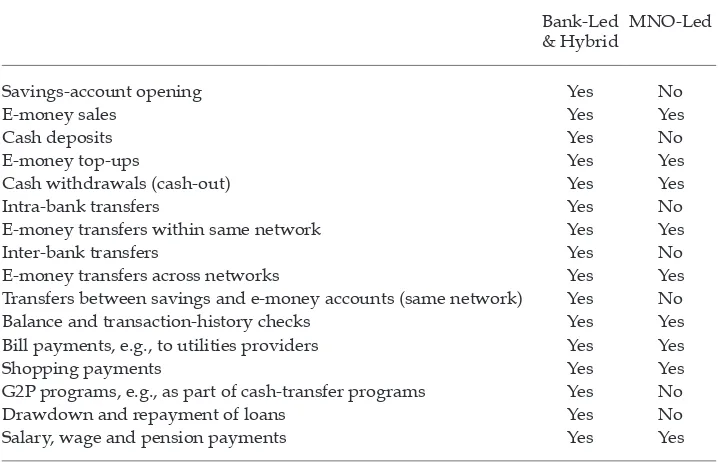

Sumatra, Central Java, West Java and East Java, Bali, East Kalimantan, and South Sulawesi. This pilot scheme will inform a forthcoming branchless-banking regu-lation. Bank-led and bank-centric deployments were permitted to offer a wider range of services during the pilot (table 8).

Cash-in and cash-out regulations

Cash merchants of licensed branchless-banking platforms (licensed e-money issu-ers) in Indonesia have long been permitted to upload value to e-money wallets without holding a BI money-remittance licence themselves. Yet only since Decem-ber 2012 have they have been permitted to perform cash-out transactions from

9 BI Regulation 11/12/2009 on Electronic Money and Circular Letter 11/11/DASP on Electronic Money. Previously, BI regulated e-money as a prepaid-card payment instru-ment, which required non-banks to operate for two years before being permitted to offer e-money (CGAP 2010: 9).

10 BI Regulation on Fund Transfers (14/23/PBI/2012)

users’ e-wallets.11 Prior to that, BI restricted cash-out services to licensed money

remitters.12 Accordingly, MNO-led mobile-money deployments were prevented

from providing cash-out services outside of branch ofices – which are concen -trated in urban areas – and were therefore unable to use their sizeable networks of airtime dealers. As of May 2011, only 1% of Telkomsel’s 500,000-strong merchant network was permitted to provide such services (Hidayati 2011: 118). With agents effectively restricted to selling airtime credit, MNOs have had little incentive to invest in developing their cash-merchant networks.

The removal of these restrictions brings Indonesia’s regulations into line with

other jurisdictions in which branchless banking is lourishing. This act is unlikely

to pose any prudential risks, since transactions are authorised in real time and cash merchants are in effect acting as resellers, exchanging e-money against their own cash balances (Mas 2012: 293–4). BI amended the pilot’s guidelines to remove restrictive transaction limits13 in bank-led and hybrid models, which should boost

the business activities of – and the scale of lending to – MSMEs.

BI’s pilot guidelines permit inancial intermediary service units (unit perantara layanan keuangan, UPLKs) of both bank-led and MNO-led deployments to offer

11 Article 4 of BI Regulation 14/23/PBI/2012. Cash merchants are referred to as cash pay-ment points (tempat penguangan tunai). E-money is one of the record-keeping systems speci-ied in the regulation’s deinitions.

12 BI Regulation 11/12/PBI/2009.

13 The guidelines set the following limits: initial deposit ≤ Rp 50,000, maximum balance at end of month ≤ Rp 1,000,000 and total transactions in one month ≤ Rp 5,000,000.

TABLE 8 Permitted Activities under Bank Indonesia’s Branchless-Banking Pilot

Bank-Led & Hybrid

MNO-Led

Savings-account opening Yes No

E-money sales Yes Yes

Cash deposits Yes No

E-money top-ups Yes Yes

Cash withdrawals (cash-out) Yes Yes

Intra-bank transfers Yes No

E-money transfers within same network Yes Yes

Inter-bank transfers Yes No

E-money transfers across networks Yes Yes Transfers between savings and e-money accounts (same network) Yes No Balance and transaction-history checks Yes Yes Bill payments, e.g., to utilities providers Yes Yes

Shopping payments Yes Yes

G2P programs, e.g., as part of cash-transfer programs Yes No

Drawdown and repayment of loans Yes No

Salary, wage and pension payments Yes Yes

Source: BI (2013: attachment A).

Note: MNO = mobile-network operator; G2P = government payments.

cash-out services for on- and cross-network transfers between registered custom-ers. In MNO-led schemes, however, cash-out services are restricted to P2P trans-fers.14 OTC transfers to unregistered participants are permitted only on non-bank

platforms and only for amounts below Rp 1 million, provided that the recipient can

comply with stringent know-your-customer (KYC) identiication requirements.15

This restriction undermines the effectiveness of mobile telephony as a channel to reach the poorest unbanked, who cannot afford mobile phones. Removing the restrictions on OTC transfers to unregistered users would enable branchless-banking deployments to reach the sizeable unbanked population among the 63% of Indonesians without mobile phones. Small, low-volume P2P transfers, P2B to

veriied vendors, and G2P payments are unlikely to support money laundering or terrorist inancing.

Merchant and agency models

The pilot enabled providers to appoint as UPLKs individuals or entities with a sound inancial history and a minimum of two years of business experience.

BI encouraged banks and MNOs to engage a range of microenterprises, such as convenience stores, motorbike garages and small coffee shops.16 By permitting

the appointment of individuals as UPLKs – despite a preference for legal entities

(Jakarta Post, 28/2/2013) – BI has recognised the dificulties in reaching the remote and rural unbanked.

A further step in improving the prospects of branchless-banking providers prof-itably serving the poorest in remote areas of the archipelago would be to explore sub-agency models. Providers could appoint mobile, street-based cash merchants to offer basic cash-in, cash-out services remotely. These merchants could rebal-ance liquidity at store-based agents, who would also serve customers with larger

transactions and potentially offer broader inancial services on behalf of banks.

Mobile, street-based cash merchants should be able to make small transactions for a lower commission, since they can operate at lower levels of liquidity, have lower overhead costs and in many instances will have a lower opportunity cost of time (Mas 2012: 294).

It is curious that BI’s pilot restricted participating UPLKs to cooperating with a

single branchless-banking provider. Regulators in other countries do not mandate cash-merchant exclusivity, though large providers in branchless-banking markets such as Kenya, the Philippines and Brazil commonly maintain exclusivity agree-ments with cash-merchant networks. Yet small and medium banks in established agent-banking markets such as Brazil share agents as a means of extending their footprint (Oxford Policy Management 2011: 7). Branchless-banking services may

not be proitable for cash merchants if they cannot act on behalf of multiple pro -viders, especially in remote areas.

14 The guidelines restrict MNO-led branchless-banking platforms from collecting cash deposits. This does not preclude cash merchants of these platforms from providing cash-in services for P2P transfers, scash-ince e-money sales are permitted (correspondence with BI oficials, May 2013).

15 Circular Letter 11/11/DASP distinguishes between registered and unregistered e-money. The former has an account limit of Rp 5 million; the latter Rp 1 million.

16 Discussions with BI oficials, May 2013.

Simpliied customer identiication

Accurate customer identiication is a central pillar of Indonesia’s commitment to the IMF’s Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) program. Yet meeting KYC requirements for new accounts can ham

-per the expansion of inancial services to the poor, who may be unable to meet formal identiication and other requirements (Dermish et al. 2012: 91). The poor’s

access to branchless banking will be improved if cash merchants are able to open accounts with providers on behalf of customers (Mas 2012: 294). In the interests of

promoting inancial inclusion, the intergovernmental Financial Action Task Force (FATF) recognises the need for lexible AML/CFT policies in low-risk scenarios

(FATF 2012).

BI regulations17 require prospective customers to furnish their driver’s licence,

passport or local-government-issued ID card to open an e-money wallet. This can be prohibitive for Indonesia’s domestic and international migrant workers: national migrants are typically reluctant to forfeit ID from their locality of origin and may need to resort to an expensive, fraudulent ID; and Indonesia’s estimated 4.3 million undocumented international migrant workers have no way of comply-ing (CGAP 2010b: 5–6).

These regulations also preclude banks18 – but not non-bank e-money

issu-ers19 – from delegating KYC account-opening procedures: a bank

representa-tive must meet the prospecrepresenta-tive customer in person. Beyond enrolling customers in branches, banks rolling out branchless-banking deployments would need to develop an internal mobile network of employees. Indonesia’s banks have there-fore been unable to build the low-cost cash-merchant networks that are a prereq-uisite to branchless banking achieving scale. The requirement for cash merchants opening e-money wallets on behalf of non-bank issuers to send a copy of the prospective customer’s ID to the issuer20 may be obstructive in areas where

facili-ties are limited.

By preventing banks from developing low-cost, cash-merchant networks, the strict KYC account-opening procedures and transfer protocols for non-banks are likely to have precluded providers from achieving scale in branchless-banking deployments and limited their reach, to the detriment of poor, remote areas of the archipelago. The pilot guidelines recognised these constraints by permitting

bank-led and hybrid deployments to delegate, to UPLKs, the opening of bank accounts

for the unbanked and underbanked segments of the population, and by requiring less stringent due diligence on these accounts, including accepting other forms of

identiication.21 Permitting less stringent KYC requirements for basic, low-value

transactional accounts is consistent with international best practice (Alexandre, Mas and Radcliffe 2011; Mas 2012: 294). It is likely to have enabled banks to reach

17 BI Regulation 3/10/PBI/2001, as amended by BI Regulations 3/23/PBI/2001 and 5/21/PBI/2003 for commercial banks; BI Regulation 5/23/PBI/2003 for rural banks. 18 See previous footnote.

19 Circular Letter 11/11/DASP. 20 Circular Letter 11/11/DASP.

21 If prospective customers lack photographic ID, a photograph must be taken at the time of application.

more unbanked customers during the pilot, and it would simplify the opening of accounts for G2P payments if it were adopted in subsequent regulations.

Status of e-money

E-money, as deined by BI, is not a bank deposit.22 Individual e-money wallets are

therefore not protected by the Indonesia Deposit Insurance Corporation. While there is no legal prohibition, BI’s stance is that e-money should not bear interest (CGAP 2010b: 9). This is not a problem for bank-led branchless-banking schemes under which e-money wallets function purely as a real-time channel for users to access deposit-insured and interest-bearing bank accounts,23 but it renders the

e-money wallets of MNO-led schemes less secure and less attractive than bank accounts.

Since e-money issuers in Indonesia are required to hold all e-money (‘the loat’)

in a dedicated, pooled bank account at a (prudentially regulated) commercial bank,24 e-money wallets need not be seen as more risky from a regulatory

per-spective than direct bank deposits (Mas 2012: 295–6). Extending deposit insurance

to individual e-money wallets (which are derivatives of the loat) and permit -ting non-bank issuers to offer interest on e-money wallets would enhance the utility of MNO-led branchless-banking schemes as a secure savings vehicle for the unbanked. This would not undermine BI’s preference for bank-led deploy-ments: banks would be able to offer higher interest to their depositors than MNOs

because they gain the full beneits of intermediation spreads, whereas e-money

issuers receive only the bank deposit rate on their cash assets (Mas 2012: 295). Should bank-led branchless-banking models fail to achieve critical mass and sub-stantial reach among the unbanked, enhancing the security and safety of e-money would assume particular importance.

Framework for interoperability and interconnection

In fragmented markets in which a number of major players compete, interoper-ability can remove frictions and unlock network effects. Despite these imperatives – and regardless of the competitive structure of banking and telecommunications markets – mandating interoperability at an early stage of the development of the branchless-banking market could be counterproductive. Setting common

techni-cal standards, resource-sharing agreements and interconnection pricing is difi -cult in sectors subject to rapid technological innovation (Economides 2006: 31). Mandating interoperability would also risk discouraging innovators from com-mercialising disruptive technologies, and providers from investing in platform development and in training and equipping cash-merchant networks (Klein and Mayer 2011). Providers can use commercial tactics to thwart mandated interoper-ability – such as subverting agent-sharing requirements by cancelling contracts with agents that are perceived to favour the competition, undermining customer-level interoperability with discriminatory pricing or marketing, or by making it

22 Article 1 of BI Regulation 11/12/2009. 23 Discussions with BI oficials, May 2013.

24 Under BI Regulation 11/12/2009 and Circular Letter 11/11/DASP, non-bank issuers are required to place 100% of the loat in a savings, current or time-deposit account at a commercial bank, while bank issuers must report the loat under immediate liabilities.

functionally dificult for customers to use competing services on their platform

(CGAP 2011). Conversely, the common practice of ‘multi-simming’ – owning multiple prepaid sim cards to take advantage of cheaper on-network calls – also enables users to overcome incompatibility among MNO-led branchless-banking

networks (Davidson and Leishmann 2012), at least for domestic P2P transfers.

Yet strong network effects in branchless banking heighten the risk of a market

tipping to an ineficient monopoly or oligopoly and becoming locked in25 –

especially if a provider enjoys a dominant market position in telecommunications or a related sector, has an early-mover advantage in branchless banking and builds its market share with a proprietary platform. In Kenya, Safaricom’s dominance in the mobile-telephony market (88% in 2011) and its rapid deployment of a size-able cash-merchant network may end up putting its M-PESA service in a winner-takes-all position (Mas 2012: 297). By increasing the utility of the underlying mobile-telephony platform for users, proprietary MNO-led branchless-banking platforms also strengthen network effects in the mobile voice-and-data market (Anderson 2010). Increasing MNO revenues per user and reducing customers’ incentives to switch operators (to ‘churn’) are among the main motivations

identi-ied by MNOs in the Philippines and Kenya for launching mobile-money services (Davidson and Leishmann 2012). The churn rate among subscribers to the Phil -ippines’s SMART Money services is only 0.5% per month, compared with 3.0% among customers who use SMART’s mobile voice or data services only (Wishart 2006: 15). This spillover effect can negate regulatory efforts to increase competi-tion in the mobile-telephony sector (Anderson 2010).

BI and Indonesia’s Business Competition Supervisory Commission (Komisi Pengawas Persaingan Usaha) should be alert to these dynamics. The risk of the market tipping is lower in Indonesia’s more fragmented sector than in Kenya and the Philippines, for example, and recent developments point to interconnec-tion. Yet Telkomsel is the market leader in mobile telephony and has an early-mover advantage in branchless banking, having launched in 2007. Its dominance could undermine the gains from increased competition since its parent, Telkom Indonesia, lost its monopoly during deregulation in 1999. Conversely, if the mar-ket does not tip and MNOs unwind their commitment to connecting their plat-forms, Indonesian consumers could face a segmented market with few network

beneits.

BI’s framework for interoperability under its e-money regulations appears to strike the right balance. It encourages providers to develop systems that allow

25 Farrell and Klemperer (2007) argued that with strong network effects a monopolistic or oligopolistic outcome of competition for the market can be eficient, provided that adopters

coordinate smoothly on the best deals, which in turn prompts vendors to compete iercely to capture the market by setting low penetration prices that dissipate ex-post monopoly rents. Economides and Flyer (1998) demonstrated that the equilibrium in markets with signiicant network externalities and total incompatibility between competing platforms is extreme market share and unequal proits, even in the absence of anti-competitive acts. However, competition for the market more frequently induces bargain-then-rip-off pricing, with dominant players extracting surplus proits once their rivals have been eliminated (Farrell and Klemperer 2007). Should a branchless-banking market tip to one network, consumers face reduced product variety and the possibility of being locked into an inferior technology or business model (Economides 2006: 29).

interconnection with other e-money systems,26 and holds out the possibility of

mandating interoperability when a consensus emerges in the industry.27 Yet BI’s

requirement for UPLK exclusivity during the pilot on branchless-banking require -ments was inconsistent with this approach. If Indonesia maintains its exclusivity requirement beyond the pilot, it risks sending a contradictory signal on interop-erability and may deter branchless-banking providers from cooperating in the delivery of services in remote areas.

Cross-border commerce and remittances

Inconsistent regulatory approaches across jurisdictions impede the uptake of branchless banking for cross-border commerce and international remittances in Indonesia and globally. Several steps could be taken within APEC or other

regional and international forums to unlock these lows on branchless-banking

platforms:

• Adopt a common international approach of permitting temporary exclusivity to stimulate innovation and investment while encouraging interconnectivity, consistent with Indonesia’s regulatory framework.

• Harmonise domestic requirements for, and remove regulatory impediments to, cross-border transfers – including by permitting provision by non-bank entities and streamlining documentation and KYC requirements (Dalberg

2012:25), in line with international best practice and AML/CFT obligations.

• Encourage an active international dialogue among regulators and central

bankers on ine-tuning regulatory best practices and the conduct of monetary

policy – particularly given regulators’ limited experience of supervising large-scale branchless-banking operations and central banks’ limited understanding

of the macro-inancial implications (Dermish et al. 2012; Klein and Mas 2012).28

A lack of awareness of the potential to send international remittances through branchless-banking platforms is preventing international remittance deploy-ments from achieving scale (Dalberg 2012). The adoption of measures to promote openness and price competition on remittance corridors, and to educate and reassure migrants working in source countries of the potential of using cross-border transfers on branchless-banking platforms, could increase competition in

international remittance markets. Sendmoneypaciic.org is a promising example in the Australasia–Paciic Islands remittance corridor.

CONCLUSIONS

Regulatory constraints have stiled the emergence of transformative branchless

banking in Indonesia, to the detriment of the country’s large unbanked

popula-tion and sizeable MSME sector, as well as to its objectives of inancial inclusion,

26 Article 27 of BI Regulation 11/12/2009. 27 Article X of Circular Letter 11/11/DASP.

28 Klein and Mas (2012) and Jack, Suri and Townsend (2010) consider the macro-inancial implications of branchless-banking schemes. Both advocate the provision of appropriate metrics on deployments, to help central banks to conduct monetary policy within existing models.