Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 20:15

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Mike Waslin

To cite this article: Mike Waslin (2003) SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 39:1, 5-26, DOI: 10.1080/00074910302004

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910302004

Published online: 17 Jun 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 52

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/03/010005-22 © 2003 Indonesia Project ANU SUMMARY

In the immediate aftermath of the 12 Oc-tober Bali bombings, the government acted to limit the repercussions by mov-ing to arrest those involved in the plan-ning and implementation of the attacks. It also took steps to stimulate the economy by increasing the 2003 budget deficit by 0.5% of GDP to 1.8%.

The start of 2003 saw the economic debate switch from the impact of the Bali bombings to the government’s decision to increase domestic electricity, fuel and telephone charges. The simultaneous price rises sparked public protests and op-position from both unions and business. The increases were initially defended, in-cluding by the president, but the govern-ment quickly backed down. This decision complicates the task of winding back the budget deficit over the next two years, and reduces budget flexibility in the run-up to the 2004 election.

Consumption continues to be the main driver of growth, although there are signs that it is waning. Third quar-ter GDP growth came in at 3.9% year on year, and GDP growth for 2002 as a whole is likely to be 3.5–3.6%. The No-vember trade data were disconcerting, with a 22.4% decline in non-oil exports, although there was some recovery in December. Inflation in December was 10%, down from a year earlier, and just above the Bank Indonesia (BI) target

range of 9–10% for the year. This and BI’s medium-term target of 6–7% seem too high, out of step with regional and world developments, and likely to under-mine Indonesia’s competitive position.

In 2003 many of the institutions and arrangements put in place following the 1997 financial crisis come to an end: the Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency (IBRA) will close; Indonesia will gradu-ate from the IMF program; and the gov-ernment will benefit from its final year of Paris Club rescheduling of official debt. The government must increasingly take ownership of its economic policies. There are signs that this is occurring, with the formation of a group to examine poli-cies for the post-IMF period. With politi-cal will and the right policy choices, budget and associated debt management can sustain macroeconomic stability in the post-IMF era, but both are likely to be susceptible to domestic political influ-ence in the lead-up to the election.

The overarching priority in alleviat-ing Indonesia’s debt burden is to accel-erate real GDP growth through effective implementation of the structural reform program, leading to improved business confidence and investment. The reality is that Indonesia will probably be stuck in a low growth scenario for a number of years unless it can speed up its struc-tural reform agenda.

SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Mike Waslin

Canberra

POLITICAL ECONOMY

The government has been able to con-tain the economic repercussions of the Bali bombings by moving swiftly to ar-rest those involved in planning and carrying out the terrorist attack that killed 202 people on 12 October 2002. While investigations are continuing, by early February the police had detained 30 people, including five main suspects (JP, 4/2/2002). The next test for the gov-ernment will be how the prosecutions are handled when the trials begin in late February.

At the same time BI sought to stabilise the rupiah by announcing that it would stand in the market against speculative activity. While there was some specula-tion, BI was able to hold the exchange rate reasonably steady, with very little reduction in international reserves. Net international reserves declined by $204 million between 7 October and 25 Octo-ber 2002, but were subsequently rebuilt by the end of the year.1 BI’s strategy of

announcing that it would stand in the market could have backfired, by provid-ing traders with a one-way bet, if BI had run down reserves substantially in de-fending the currency, increasing the like-lihood of depreciation.

The impact of the bombings on Bali’s economy was also mitigated through the relocation of government conferences to Bali, promotion of domestic tourism, and package deals from other Asian countries. The question now is how well tourism will hold up following the end of the Indonesian holiday period.

In early 2003 the economic debate switched from the impact of the Bali bombings to the decision to increase elec-tricity, fuel and telephone tariffs from 1 January 2003. Price rises for electricity (6%), fuel (3–23%) and telecommunica-tions (15%) took effect on 1 January (JP, 3/1/2003: 13), and brought public pro-tests and combined opposition from the

unions and business. Although receiving substantial press coverage, the public protests were nevertheless relatively small (up to 5,000 people), considering the convergence of support from the vari-ous interest groups.

The protests seem to have taken the authorities by surprise, as there had been little public comment on the in-creases when they were first announced in connection with the 2003 budget. Ini-tially it seemed the government would stand fast against this opposition and, in a rare comment on economic matters, President Megawati publicly defended the price rises. However, the govern-ment quickly backed down, first an-nouncing that it would take a week to review the policy and then, on 20 Janu-ary, on the eve of the meeting in Bali of the Consultative Group on Indonesia (CGI), stating that it would wind back the increases.

While retaining the subsidies on fuel and electricity, the government an-nounced that it would be able to main-tain the revised 2003 budget deficit at 1.8% of GDP through the use of contin-gency reserves and increased revenue from higher oil prices. Donors at the CGI meeting in January pledged up to $2.7 billion for financial year 2003, meeting the government’s target range of $2.4–2.8 billion for funding the 2003 budget. The immediate fiscal ramifications of the de-cision were therefore easily accommo-dated. However, the decision to back down on plans for subsidy cuts could make it more difficult to wind back the budget deficit over the next two years, and will reduce budget flexibility in the lead-up to the 2004 election.

If the current increase in world oil prices is only a temporary spike, the gov-ernment will be able to use subsequent falls in the world price to wind back the subsidy. Controlling utility prices is much more problematic. Electricity and

telephone infrastructure are badly in need of investment, and maintaining below-market tariffs will hold back such investment. This was highlighted by PT Telkom’s announcement that it had can-celled a planned investment worth $300 million following the government’s de-cision to delay the 15% tariff increase (Business News, 17/1/2003: 4).

In moves reminiscent of the on-again-off-again 2001 fuel price increases, the Director General for Posts and Telecom-munications announced on 28 January that the government still planned to imple-ment the telephone tariff increases within one to two months, but this was denied the next day by Minister Agum Gumelar.

REAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS

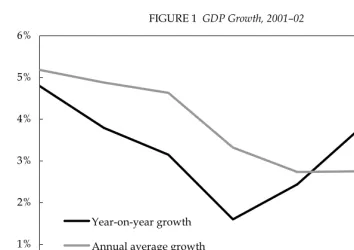

Indonesia’s recent economic perfor-mance can be portrayed in two slightly different ways, depending on whether yearly average or year-on-year compari-sons are made (figure 1). In year-on-year

terms, growth has steadily improved from a low of 1.6% in the fourth quarter of 2001 to 3.9% in the third quarter of 2002. In contrast, when measured in an-nual average terms, growth has re-mained relatively flat since the first quarter of 2002 at just under 3%. With a constant rate of growth, both of these measures should converge. A worrying sign is that growth appears to be settling around the 3.5–4% range. In part the slowdown is due to slower world eco-nomic growth, but there are questions about Indonesia’s ability to take advan-tage of any upswing in world economic activity when it occurs.

Among policy makers and local com-mentators, the general rule of thumb is that Indonesia needs approximately 6% growth to accommodate the expanding workforce, and to make headway in re-integrating displaced workers within the formal economy. According to BI, growth of 3.5% in 2002 was only sufficient to

0% 1% 2% 3% 4% 5% 6%

Q1 01 Q2 01 Q3 01 Q4 01 Q1 02 Q2 02 Q3 02

Year-on-year growth

Annual average growth

FIGURE 1 GDP Growth, 2001–02

Source: Statistics Indonesia (BPS).

absorb 1.2 million workers out of the 2.5 million expansion in the labour force.

Consumption

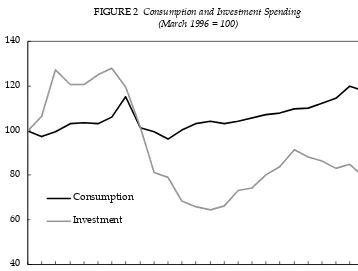

Consumption continues to be the main driver of economic growth. As shown in figure 2, it is now around 20% above the pre-crisis level; in contrast, invest-ment is approximately 20% below its pre-crisis level.2

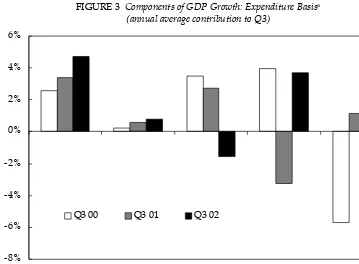

On an annual average basis, private consumption contributed 4.8% to GDP growth in the third quarter of 2002, up on the 3.4% and 2.6% contributions for the same period in 2001 and 2000 (fig-ure 3). Nevertheless there are signs that this component may be waning as the major source of GDP growth. In year-on-year terms, private consumption’s rate of growth declined from 9.2% in the fourth quarter of 2001 to 4.7% in the third quarter of 2002.

Consumption grew faster than GDP in 2001 and 2002, so the current slowdown

in its growth was inevitable. Neverthe-less, it will continue to be the major driver of growth in 2003. Even consumption growth of around 5% is sufficient to pro-vide GDP growth of 3–3.5%.

Partial indicators reveal that the con-sumption cycle is more advanced in Indonesia than in other countries in the region. For example, average monthly car sales have been close to their pre-crisis level of 30,000 units for the past three years. In comparison, car sales in Thailand and the Philippines remain below pre-crisis levels. Motorcycle sales are regarded as an indicator of the wellbeing of middle income earners. The fasting month of Ramadan (6 No-vember to 5 December) makes it diffi-cult to assess trends in motorcycle sales on a month-on-month basis. However, on a 3-month moving average basis, it is clear that the extraordinary growth that occurred during early 2000, when motorcycle sales rose by more than

40 60 80 100 120 140

Q1 96 Q1 97 Q1 98 Q1 99 Q1 00 Q1 01 Q1 02

Consumption

Investment

FIGURE 2 Consumption and Investment Spending (March 1996 = 100)

Source: BPS.

100%, has now passed, as pent-up de-mand has been satisfied. Sales slowed over the course of 2002, from 58.9% in March to 38.8% in October and 17% in November. Domestic cement consump-tion continues to expand, albeit at a slower pace; it rose by 6.8% in 2002, down from 13.7% in 2001 (CEIC Asia Database).

Considering the importance of con-sumption to Indonesian economic growth, there was a real risk that the Bali bombings would seriously undermine consumer confidence, resulting in in-creased precautionary savings and re-duced consumption. Surveys by the Danareksa Research Institute (DRI 2002) indicate that, despite a 4.8% fall in the November consumer confidence index to 94.1, buying intentions remained

re-silient, with the percentage of shoppers intending to buy durables over the next six months increasing from 21.6% to just under 24%.

Substantial minimum wage increases in 2001 and 2002 would have acted to support consumption growth, particu-larly since the lower income groups have a higher marginal propensity to con-sume. In 2003 the minimum wage in-creases are substantially lower, with nominal monthly minimum wages ris-ing by 6.8% in Jakarta, from Rp 591,000 to Rp 631,000. This will be the first time since 1998 that real minimum wages have not increased in Jakarta. In other provinces, minimum wage increases range from 4.6% in the district of Cilacap (Central Java) to 28.8% in the province of Nangroe Aceh.

FIGURE 3 Components of GDP Growth: Expenditure Basisa

(annual average contribution to Q3)

-8% -6% -4% -2% 0% 2% 4% 6%

Q3 00 Q3 01 Q3 02

Private consumption

Government consumption

Investment Net exports Stocks/statistical discrepancy

aThe contribution of each component to GDP growth is the absolute change in that

compo-nent as a percentage of the initial level of GDP.

Source: BPS.

Investment

While investment improved marginally in Q2 and Q3 2002, as measured in the national accounts, it continues to be a laggard in the Indonesian growth story, remaining about 20% below pre-crisis levels (figure 3). The obstacles to invest-ment in Indonesia have been canvassed widely in the past, and recently restated by the National Planning Agency (Bap-penas 2003). They include regional se-curity; law enforcement; labour market problems; the overlapping responsibili-ties of the central and provincial govern-ments; regulatory burdens; distortions in the tax system; and increased compe-tition from other developing countries. Investor perceptions, particularly among companies not already operat-ing within Indonesia, are affected by the political climate and the treatment given to foreign investors. The period under review saw a number of inci-dents that continued to undermine in-vestor confidence. Not least were the Bali bombings, which again raised se-curity concerns, and have imposed ad-ditional costs on doing business in Indonesia as companies increase secu-rity for their businesses and families. In addition, the use of criminal charges in a commercial dispute again emerged as a problem, when Indian executives of Polaris Software Laboratories (par-tially owned by Citibank) in dispute with Bank Artha Graha were arrested and gaoled for one week on fraud charges (AWSJ, 18/12/2002). The case is reminiscent of another in which se-nior executives of the Manulife com-pany were gaoled in 2001 in a dispute over ownership of the company.

The government’s policy ‘flip-flop’ on telephone and electricity charges has a direct effect on the profitability, and therefore the desirability, of investing in

these sectors. It may also impact on the willingness of companies to invest in state-owned enterprises more generally on the basis of expected price changes or, equally importantly, of assurances that possible adverse policy changes will not occur. In the case of the recent pri-vatisation of Indosat, the sale was con-ducted in anticipation of the announced telephone tariff increases, and the sale price presumably reflected the proposed rises.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) ap-provals declined by 35%, to $9.7 billion in 2002 from $15.1 billion in 2001, and 38% of the approvals were for the ex-pansion of existing plants. According to the Investment Coordinating Board, foreign investment approvals were con-centrated in the trading and other ser-vices, metal, machinery, electronics, transport, storage and communica-tions, and hotel and restaurant sectors (AWSJ, 8/1/2002). Domestic invest-ment approvals fell by 57%, to Rp 25.3 billion from Rp 58.6 billion.

The dramatic decline in the approv-als data does not accord with the na-tional accounts figures, which show more modest declines and even increas-ing investment in the second and third quarters of 2002. Approvals data are no-toriously inaccurate predictors of actual investment, but they do provide an in-dication that there are fewer investment projects in the pipeline, and that the prospects for a speedy recovery in investment are slim.

Indonesia is not alone in having de-clining FDI flows, or in having gross fixed capital formation remain below pre-crisis levels. FDI to the five crisis countries fell to $6 billion in 2001, from $12.6 billion in 2000 and $19.6 billion in 1996 (UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2002, cited in World Bank 2002a).

Figure 4, which indexes investment back to pre-crisis levels, shows that in-vestment remains below its 1997 level in Thailand, and has fallen further there relative to its pre-crisis level than is the case in Indonesia.

Even though its investment recovery has been faster than that of Thailand, Indonesia’s problems with the rule of law, corruption, security, and enforce-ment of property rights mean that it is likely to find it harder than other re-gional economies to attract FDI in an en-vironment where total flows to the region are diminishing. With increased competition for FDI from China and other emerging markets, it is improbable that investment flows will ever return to their pre-crisis levels for an extended period. Growth will need to be driven by improving productivity.

Production

Measured on a production basis, annual average GDP growth slowed in the ma-jority of sectors in 2000–02 (figure 5). Most notable was the fall in the contri-bution of the manufacturing sector. The declining competitiveness of that sector is highlighted by Sony’s decision to move its audio equipment production to Malaysia. In addition, there have been continual warnings of declining com-petitiveness in the textile and footwear subsectors (James, Ray and Minor 2003, in this issue; Alisjahbana and Manning 2002).

International Trade

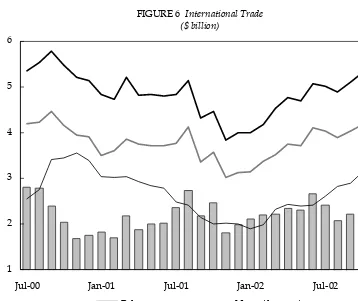

The November 2002 trade data caused alarm, with a 22.4% decline in non-oil exports over the previous month. Non-oil exports partially recovered in

FIGURE 4 Southeast Asia: Gross Fixed Capital Investment (Q4 1996 = 100)

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

Dec-96 Dec-97 Dec-98 Dec-99 Dec-00 Dec-01

Indonesia Thailand

Philippines Malaysia

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

FIGURE 5 Components of GDP Growth: Production Basis (annual average contribution to Q3)

Source: BPS.

-0.5% 0.0% 0.5% 1.0% 1.5% 2.0% 2.5%

Q3 00 Q3 01 Q3 02 Agriculture,

forestry & fisheries

Mining

Manufacturing

Services Finance

Transport Hotels &

restaurants

Construction Electricity,

gas & water

December, rising by 11.8%, and total ex-ports were 20.3% higher than in Decem-ber 2001 (figure 6). The NovemDecem-ber decline in exports was concentrated in electrical machinery (down 41.6%); machines and mechanical appliances (down 54.3%); animal and vegetable fats and oils (down 47.5%); and non-knitted garments (down 34.5%). One possible explanation for the disruption in trade is the decision by Lloyds to re-move Indonesia from the list of areas excluded from war risk, thereby in-creasing uncertainty and shipping costs to and from the country.3 The

down-ward movement in November was sub-stantial, and further data are required to determine whether there has been a structural decline in Indonesian trade. Before November, non-oil exports had been improving consistently over the course of 2002. Accordingly, even if Indonesia was able to hold its exports

constant on a month-on-month basis, it would have been able to post reasonably strong year-on-year export growth.

Indonesia recorded a balance of pay-ments surplus in 2002, allowing BI to increase foreign reserves to $31.6 billion from $28 billion in December 2001. The rise in foreign reserves was attributable to increased oil and gas export revenues, drawdowns on foreign government loans, and IBRA asset sales.

Bali: The Impact of the Bombings

Initial indications are that the direct ef-fects of the Bali bombings on the Indo-nesian economy will be relatively modest. In assessing its economic im-pact it is important to distinguish be-tween economic developments already in train and consequences flowing from the bomb blast. The official forecast was for growth of around 4% in 2002. How-ever, issues of declining competitiveness

1 2 3 4 5 6

Jul-00 Jan-01 Jul-01 Jan-02 Jul-02

Balance Non-oil exports

Total exports Imports

FIGURE 6 International Trade ($ billion)

Source: BPS.

and decelerating growth in consumer demand meant that growth prospects for 2002 had already been reduced to 3.6–3.8%. The additional reduction to growth in 2002 due to the decline in the tourist industry would be only mar-ginal. BI’s preliminary estimate of GDP growth for 2002 is 3.5% for the year. This implies that the impact of the Bali bombings on GDP was only around 0.1–0.2% in 2002.

The full year effect for 2003 will de-pend on whether Bali was an isolated terrorist incident or whether attacks are repeated across the nation. By moving swiftly to arrest those involved in the bombings the government may have managed to contain the economic damage.

Even before the bombings, the budget assumption of 5% growth in 2003 was considered overly ambitious by the mar-ket. The Consensus Economics growth forecast for Indonesia in September was only 4.2%.4 In revising the budget after

the Bali bombings, the government re-duced its growth rate assumption to 4%, while the November forecast by Consen-sus Economics was 3.6%.

Forecasts of the impact on the economy immediately after the bomb-ings concentrated on the direct con-sequences flowing from the reduction in tourism (World Bank 2002b). Fore-casts of a reduction in GDP of around 0.7% in 2003 were based on the direct effect on the tourism, transport and services sectors. Analysis was based

on the experience following the 1987 bombing of Luxor in Egypt. The flow-on effects flow-on cflow-onsumptiflow-on could not be predicted. The risk was that con-sumption could evaporate as consum-ers increased their precautionary savings in the face of heightened un-certainty.

The fact that consumer spending in-tentions have held up despite a decline in consumer confidence in the post-Bali period suggests that the government’s swift action to increase security and ac-tively pursue the terrorists limited the flow-on effects to the rest of the Indone-sian economy. Nevertheless, the direct impact on the Balinese economy has been substantial. Direct tourist arrivals to Bali fell by around 80% to 31,497 between September and November, recovering to 64,352 in December (World Bank 2003: 3).Bappenas (2003: 11–16) estimates that without speedy economic recovery the loss of employment in Bali could be in the range of 100,000–120,000 persons. To limit the impact on the Balinese economy the government has:

• increased promotion of Bali, includ-ing sponsorship of international sport-ing events;

• redirected government business by holding all conferences in Bali; and • accelerated local government infra-structure spending (including water, drainage, sewerage systems and pave-ment projects) in and around the tourist centres of Kuta and Legian.

FINANCE AND BANKING Financial Markets

The rupiah ended the year as one of the best performing currencies in the re-gion, appreciating by 10.1% on average over 2002, with lower volatility than during the previous year (Sabirin 2003). Despite the uncertainties after Bali, BI was able to hold the currency relatively

stable: it depreciated by about 2.5% in the immediate aftermath of the bomb-ings, from Rp 9,027/$ on 11 October to Rp 9,249/$ on 17 October 2002, but recovered to finish the year at Rp 8,975/$ (Pacific Exchange Rate Ser-vice, University of British Columbia, http://pacific.commerce.ubc.ca/xr).

Monetary Policy

Inflation in December 2002 was 10.03%, down from its level a year earlier, and just above BI’s target range of 9–10% for the year. BI is targeting an inflation rate of 9% for 2003; included in that target is an estimated impact of around 3% for the effect of administered price increases and provincial wage increases. The question is whether BI will revise its in-flation target downwards following the government’s decision to wind back the administered price increases.

The operation of monetary policy is in a transitionary phase. Officially, BI tar-gets base money in the implementation of monetary policy. The targets are an-nounced in the government’s Letter of Intent to the IMF. Yet at the same time BI is moving to inflation targeting, and has established a medium-term target of 6–7% inflation by 2006. As a result, mon-etary policy is being implemented with an eye on both base money and inflation.5

BI’s target for base money growth of 13% in 2003 is consistent with its inflation tar-get of 9% and the growth forecast of 4%. During 2002, BI reduced the interest rate on one-month Bank Indonesia Certifi-cates (SBIs) by 469 basis points, from 17.62% to 12.93% (Sabirin 2003).

Growth of cash in circulation de-clined during the first half of 2002, from rates in excess of 20% in 2001 to around 7% in mid 2002. BI attributed the slower rate of growth to a reduction in discre-tionary demand for cash following the election of Megawati as president and

the greater political stability. From about July, the increase in currency in circulation resumed its historical trend. The spike in currency in circulation during November–December 2002 (fig-ure 7) reflects the extended Idul Fitri and Christmas holiday period, and possibly increased holdings of discretionary bal-ances following the Bali bombings. The absence of disturbances over the holiday period has seen cash return to the bank-ing system.

While the government’s progress in reducing inflation during 2002 was good, it was not exceptional: the pace of decline slowed from mid 2002, when the inflation rate hovered around 10.5%. BI’s 2003 and medium-term inflation targets are too high in a world where low infla-tion has become the norm and there is concern over possible deflation. In this environment, Indonesia’s competitive

position is being eroded as the real ex-change rate appreciates.

The Banking Sector

The health of the banking sector im-proved in the past couple of years, with negative net interest margins being re-placed by an average return on assets of 1.86% for the top 22 banks in the first half of 2002. Nevertheless the banking system is far from being restored to full health.

According to the governor of BI, the system as a whole has net non-performing loans (NPLs) below the maximum level of 5% set by the cen-tral bank, although some banks have NPLs above that level. BI has an-nounced that because of ‘factors out-side the control of individual banks’, it will delay implementation of the 5% policy (Sabirin 2003). Those banks

40 60 80 100 120

Mar-98 Sep-98 Mar-99 Sep-99 Mar-00 Sep-00 Mar-01 Sep-01 Mar-02 Sep-02 Currency in circulation

Trendline

FIGURE 7 Currency in Circulation (Rp trillion)

Source: Bank Indonesia.

currently failing the test are required to report on how they are going to meet the target in 2003. On a gross basis, NPLs were 10.2% at the end of Octo-ber; private sector estimates give NPLs of over 40% for some banks. Clearly, the long-term stability of the banking sys-tem can only be assured when all banks are adequately capitalised and provi-sioned: it is essential that all banks at least adhere to the 5% NPL target or that appropriate action is taken.

New credit extended by banks in-creased by Rp 72 trillion between Janu-ary and November, 27% higher than in the same period a year earlier (Sabirin 2003). This growth in new lending over-states the real increase in credit, because it includes funds provided to borrow-ers to purchase loans from IBRA, reflect-ing a portfolio switch in the way those loans were recorded. In addition, the percentage increase in lending is over-stated because banks continue to hold only a small proportion of their assets as loans.

FISCAL POLICY

The actual 2002 budget deficit is esti-mated at 1.6% of GDP, or Rp 27 trillion below the budget estimate of 2.4%. Do-mestic revenues were Rp 5 trillion lower than budgeted, but this was more than offset by lower expenditures, in particu-lar underspending of Rp 7.2 trillion on development. Underspending on devel-opment has been a consistent feature of budget outcomes in recent years, and comes at a longer-term cost to future growth.

The budget for 2003 was revised in the wake of the Bali bombings, to pro-vide increased fiscal stimulus of Rp 8.1 trillion, or 0.5% of GDP. An extra Rp 10.6 trillion was allocated for devel-opment spending, but it remains to be seen whether all the funds will be dis-bursed.

The 2003 budget originally planned to cut subsidies from Rp 30.5 trillion to Rp 15.9 trillion, raising the price of petrol from its current level of 75% of the world price to 100%. The budget allocated Rp 4.1 trillion to fund power subsidies. The original proposal was for power price increases of 14.5% per quarter. However, parliament approved quar-terly rises of only 6%. Increased prices are necessary to improve the return on investment in the electricity sector in or-der to justify new investments. The state electricity company, PLN, is quoted as saying that it has made no new invest-ments since 1998 owing to a lack of funds (JP, 6/1/2003).6

Following public protests, the gov-ernment at first announced its intention to reduce taxation imposts on businesses by Rp 6 trillion to offset the cost of the planned administrative price rises. The proposed cuts involve exempting cer-tain goods from the luxury tax, includ-ing cellular phones, television sets, washing machines, refrigerators, VCRs, DVDs and audio recorders. Despite the decision to wind back the price in-creases, the tax cuts are to be retained as a means of improving business com-petitiveness. Notably, the goods benefit-ing from the taxation concession were the same goods that suffered the sharp decline in exports in November 2002.

STRUCTURAL POLICY The IMF Program

The government signed a further Letter of Intent (LOI) to the IMF on 20 Novem-ber, almost three months after the origi-nal date for completion of the review of the previous IMF program. Finalisation of the LOI had been delayed pending progress on a number of areas of reform. One performance criterion still await-ing finalisation is the Bank Indonesia Liquidity Support (BLBI) settlement, an agreement on how to apportion between

the government and BI the cost of liquid-ity support provided to the banking sys-tem during the financial crisis. It is a matter of semantics whether this debt is recorded on the government’s books or those of BI, since it remains a cost to the public sector (Alisjahbana and Manning 2002: 291), but this does have a presen-tational effect on the interest cost re-corded in the budget. Finalisation of the BLBI settlement would allow this long-running political issue to be settled. More importantly, it would remove one of the impediments to parliament’s com-pleting its deliberation of revisions to the central bank legislation to make BI more accountable.

Progress on bank sales has been much slower than envisaged under the pro-gram at the beginning of 2002. The sale of Bank Niaga, originally slated for June, was not completed until November. As a result, the sale of Bank Danamon and preparations for the sale of a stake in Bank Mandiri were also delayed.7

Privatisation receipts were also slow to materialise. There were initial port-folio offerings in Indosat and Telkom in the first half of the year. However, sub-stantial progress in meeting the budget privatisation target was not achieved until the sale of a majority stake in Indo-sat was finalised at the end of the year. The privatisations that have been suc-cessful to date have tended to be portfo-lio sales or strategic sales of corporations already listed on the stock exchange. This is because the initial hurdle of gain-ing public acceptance for some private ownership has, in theory, already been passed. What has yet to occur is strate-gic sales of enterprises wholly owned by the government, i.e. state-owned com-panies not already listed on the stock exchange.

The legal framework for Treasury bond auctions was finally established with the passage of the enabling

legis-lation in September. The first auction took place in December (see discussion of official debt below).

An area of recent controversy has been the bank shareholder settlement agreements. IBRA created a ‘stick and carrot’ approach for dealing with the debt of former bank owners. The pro-cess adopted involved an initial deter-mination as to which shareholders had been cooperative. Under the so-called ‘release and discharge’ policy, owners deemed cooperative in settling their debts to the government would be dis-charged from any further obligation. The remaining shareholders would have 90 days in which to make payment or face legal action. This policy has been criticised by NGO groups as being a se-rious blow to justice, in that individuals have not been required to account for their actions.

Under the IMF’s June 2002 require-ments for structural reform, the govern-ment had to finalise and publish by July its initial determination of the former bank owners’ compliance for each of the settlement agreements. This process was not completed until October. In Novem-ber 2002, IBRA announced that it would take legal action against five former bank shareholders who had failed to pay what they owed the government. The former owner of Bank Risad Salim International avoided legal action by paying Rp 27 bil-lion in cash in October, on top of assets previously surrendered to IBRA (JP, 12/11/2002).

An area that has slipped from recent LOIs has been the structural reform agenda and, in particular, legal reform, with the exception of the establishment of the Anti-Corruption Commission. This was targeted as a June 2002 structural requirement, but the enabling legislation to establish the commission was not passed until the end of November (Business News No. 6847, 2/12/2002: 3).

Finance Minister Boediono has identified structural reforms aimed at improving Indonesia’s competitiveness as the main theme of policy for 2003, so it is likely that this will be taken up in the current review of the IMF program, scheduled to be completed by mid February.

It is reported that the government has reached agreement with the IMF over the terms of the next LOI, but it is yet to be released. Its main objective will be to set the path of policy for 2003, the last year of the IMF program.

In 2002, the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) decided that Indone-sia should graduate from the IMF pro-gram at the end of 2003. The country is already in the final stages of the pro-gram, and is now repaying to the IMF more than it is receiving in new loans. During 2002, the government repaid approximately $2.3 billion (Sabirin 2003: 5), with the result that indebtedness to the IMF fell by $1.1 billion over the course of the year. The issue for Indone-sia is not the balance of payments sup-port that the Fund provides, but access to official credit.

Bank Restructuring

IBRA is scheduled to be wound up by February 2004, but its chair, Syafrudin Temenggung, has publicly stated his desire to wind up the organisation by September 2003. With IBRA having less than a year to run, it is worthwhile to reflect on its original objectives and what it has achieved.

IBRA was established in January 1998 (Johnson 1998: 47–9) with three primary objectives:

• to reorganise and support the bank-ing system (includbank-ing returnbank-ing to the private sector banks in which the govern-ment had acquired a substantial interest);

• to collect funds through the sale of assets of previous bank owners; and

• to restructure and dispose of problem loans moved to IBRA as part of the bank restructuring.

IBRA was granted quasi-judicial rights under Government Regulation 17 of 1999 (known as PP17). The regulation provides IBRA with the authority ‘to control and/or sell goods or assets which have been transferred to obtain compensation in respect of the … fault, negligence and/or improper transaction on the part of bank shareholders, direc-tors and commissioners’ (IMF 2002). In effect the regulation gives IBRA the au-thority to foreclose on debtors without recourse to the courts, but the difficul-ties of enforcement remain.

IBRA took some time to begin its work, with much of 1998–99 spent trying to as-sess the scope of the problem. It was not until 1999 that the recapitalisation of the banks got under way, and even then it did not proceed smoothly. There were many delays, owing to concern about the interest cost implications for the budget. Because of rising interest rates, the gov-ernment issued banks with an increasing proportion of fixed rate recapitalisation bonds as the process continued. The de-lay in recapitalising the banks and the is-suing of fixed rate bonds saw many banks continue to earn negative net in-terest margins. Only during 2002, when interest rates began to decline, did bank profitability improve.

Despite criticism of IBRA’s poor per-formance in pursuing debtors and former bank owners, it has broadly met its budgetary targets (table 1). However, in IBRA’s case, meeting budgetary tar-gets and pursuing defaulting debtors are not the same thing. Until 2001, around 60% of IBRA’s cash revenue came from loan assets, and mainly in the form of debt service (IMF 2002). (IBRA received performing as well as non-performing loans when it took over the failed banks.)

By the end of 2001, IBRA still held over 86% of the assets that had been transferred to it. Despite meeting its budgetary commitments, it has not achieved the rapid disposal of assets to repurchase recapitalisation bonds that was originally envisaged. The most vis-ible example is its slow pace in return-ing banks to the private sector. The September 2000 ‘Supplementary Memo-randum of Economic and Financial Poli-cies’ signed with the IMF envisaged the sale of Bank Central Asia (BCA) and Bank Niaga by the end of 2000, and completion of the bank divestiture pro-cess by the end of 2001. In the event, the sale of the two banks was not finalised until the end of 2002, two years later than originally planned, and the other banks were yet to be sold at the time of writing. As we have seen, the recovery of assets from former bank owners through the bank shareholder settle-ment agreesettle-ments has also been slow.

The year 2002 saw a marked accelera-tion in asset disposal. The most contro-versial aspect was the decision to sell loans on an obligor basis, rather than as a pool of loans from different borrow-ers. Under the obligor system, loans to companies within the same corporate group were packaged together. The

con-cern was that sales by obligor provided a simple mechanism by which debtors could buy back their own debt. In a sys-tem where there is effective enforcement of insolvency laws, debtors would not be in a position to buy back their own debt because those resources would al-ready be available to creditors. In weaker enforcement systems, the pub-lic choice issue is whether to maximise recovery, which might be achieved by the acquisition of the debt by the debtor, or to minimise the moral hazard inher-ent in borrowers believing they can de-fault on their debts and buy back the debt at a discount at a later date. In prac-tice, whether a loan is sold back to an obligor (debtor) or to an unrelated third party, there is likely to be little differ-ence in the final outcome: the third party will seek to maximise returns, and that is likely to occur through a settlement with the debtor for approximately what the debtor would have been prepared to pay for the loan.

For 2003, IBRA has a cash recovery target of Rp 18 trillion. Assuming that this is met, IBRA’s total recoveries over its life will equal approximately Rp 161 trillion, representing a recovery rate of less than 25% on the total amount of recapitalisa-tion bonds and bonds issued to BI. Note

TABLE 1 IBRA’s Budgetary Performance

1999/2000 2000 2001 2002

Actual Budget Actual Budget Actual Budget Actuala Budget

Cash 12.9 17.0 20.2 18.9 28.0 27 40.7 35.3

Bonds 4.2 29.5 10 7.5 7.5

aAs at 23 December 2002.

Source:IBRA, Monthly Report, various issues (www.bppn.go.id).

that this is an overstatement, as it ignores the time value of money and includes in-terest income on performing loans.

What Is Left to Be Achieved. There are five categories of assets that IBRA has yet to dispose of:

• loans left over from the sale by obli-gor: there were approximately Rp 50– 60 trillion in loans that failed to sell as part of the sale of recent loans by obli-gor; these are to be packaged in bundles of approximately Rp 10 trillion and sold;

• loans not offered for sale—i.e. loans greater than Rp 750 billion (the top five obligors, e.g. Texmaco), plus loans that are subject to legal action;

• equity in the BTO banks (‘banks taken over’ by IBRA)—Bank Danamon, Bank Lippo and Bank Bali (incorporating Bank Universal, Bank Patriot, Bank Artha Media and Bank Prima Express); • the property portfolio: branches of banks that have been closed, and secu-rity on loans that have been foreclosed, are being offered through a property asset sales program (PPAP). Consider-ation is also being given to developing an industry-based strategy to encourage a secondary mortgage market;

• recovery of money from former bank shareholders through the bank share-holder settlement agreements.

IBRA must now dispose of its least saleable assets. The easiest category of assets to sell should be equity in the banks that IBRA has acquired, although this has not proved easy in the past, with parliament taking an increasing interest in the process.

Privatisation

The privatisation process has been a dif-ficult one for the government. Over the past few years it was supposed to con-tribute to the financing of the budget deficit. In 2002 privatisation proceeds reached and even exceeded the budget

target for the first time, with a realisation of Rp 7.6 trillion. This was achieved mainly though the partial sale of Indo-sat. The process proceeded reasonably smoothly until the Indosat sale was finalised, when there were protests by employees seeking to have the sale over-turned.

The 2003 budget targets privatisation proceeds of Rp 8 trillion. Given likely rising nationalist sentiment in the lead-up to the 2004 election, it will be a hard task for the government to achieve this target. However, following the decision to wind back the removal of the fuel and electricity subsidies, there will be strong fiscal pressure to press ahead with the privatisation program.

The government has announced its intention to sell interests in the follow-ing companies durfollow-ing 2003: Bank Rak-yat Indonesia (BRI); construction company PT Adhi Karya; gas distribu-tion company PT Perusahaan Gas Negara (PGN); housing contractor PT Pembangunan Perumahan; airport op-erator Angkasa Pura II; securities firm PT Danareksa Securities; insurance firm Asuransi Kredit Indonesia (Askrindo); and real estate companies Kawasan Berikat Nusantara, Jakarta Industrial Estate Pulo Gadung and Surabaya In-dustrial Estate Rungkut. The sales are still subject to parliamentary approval. Added to this list are companies not sold during 2002, such as Bank Man-diri, PT Kimia Farma and PT Ankasa Pura I (JP, 19/11/2002).

Privatisation will need to assume an even larger role in financing the 2004 budget deficit, in view of the expected closure of IBRA by the end of the year. While privatisation is important to the funding of the budget deficit, it could be argued that the government is simply substituting one asset class for another: its net asset position remains unchanged if it uses the proceeds of privatisation to

repay debt. The major gains from priva-tisation are that it puts private sector rather than government capital at risk (an important consideration in the banking system) and that it has the potential for substantial efficiency gains.

OFFICIAL DEBT

Management of public debt remains a contentious issue, and there have been calls for foreign debt forgiveness on the basis that borrowings by the Soeharto government were misused. External debt increased from 25.6% of GDP in 1996 to 42.8% in 2001. This rise was driven largely by exchange rate depre-ciation: in dollar terms debt increased only from $50.9 billion in December 1997 to $61.6 billion in February 2002, reflect-ing increased borrowreflect-ings from donors and the international development banks.

The issuance of domestic bonds has been viewed by the public as meeting the cost of bailing out the conglomerates rather than the cost of protecting bank depositors.8 Domestically, the

govern-ment has issued Rp 647.2 trillion in bonds to recapitalise the banking system and compensate BI for liquidity support provided to banks. As a result, domes-tic debt increased from zero in 1996 to 48.6% of GDP in 2001.

Given the perception that both for-eign and domestic debt have been inappropriately incurred, it is under-standable that there has been a reluc-tance on the part of NGOs and other commentators even to accept the need to service the debt, let alone develop a strategy for managing it.

Indonesia has nevertheless made sig-nificant and, in some respects, unexpect-edly good progress in reducing its debt burden. The country’s public debt pro-file had improved from over 100% of GDP in 2000 to 72% by the end of 2002.9

This improvement has been driven by

strong growth in nominal GDP and ap-preciation of the rupiah. The failure of BI to control inflation has had the unin-tended consequence of partially inflat-ing away domestic debt. However, this is a reduction in the relative debt bur-den only: absolute levels of government debt have not been reduced, as IBRA has failed to recover assets of sufficient quantity to repay a substantial part of the debt.

In terms of the government’s overall balance sheet, the decline in the value of the debt is roughly matched by a de-cline in the value of assets, because bonds are largely held by state banks and banks in which the government has acquired a majority stake. Inflating away the real value of the government’s debt also inflates away the real value of the government’s equity holdings in the banking system.

The improvement in Indonesia’s ratio of public debt to GDP means that the country’s debt is no longer substantially out of line with that of other regional economies. Thailand’s public sector debt is expected to rise to a little over 60% of GDP in fiscal year 2002, and the Philip-pines’ public debt is also estimated at around 60% of GDP.

Work by the World Bank shows that the ratio of Indonesia’s debt to GDP could fall below 50% by 2008 and reach its pre-crisis level of 25% by 2016 (World Bank 2002b). The key to sustainability is accelerating real GDP growth; fiscal policy geared to achieving primary sur-pluses (i.e. excluding interest cost) of about 3% of GDP; and asset sales and privatisations aimed at financing defi-cits, so that additional debt is not added to the stock, and any additional proceeds are directed at reducing public debt.

The substantial rise in government debt has imposed a significant strain on the budget. The interest carrying cost peaked in 2001, when interest payments

totalled Rp 95.5 trillion, or 32% of rev-enue. This was also the year in which the cost of subsidies peaked, with the result that payments on interest and sub-sidies represented 55% of revenue. The brunt of the interest and subsidy carry-ing cost was borne by development spending, which fell to 13.1% of revenue in 2001 from 37.6% in 1996–97. A decline in domestic interest rates and a rise in revenue have resulted in the interest car-rying cost falling to a projected 24.4% of revenue in 2003, enabling the develop-ment budget to be expanded to 19.4% of revenue.

The notional external interest cost has remained relatively stable, with bud-geted interest decreasing from Rp 29.3 trillion in 2001 to Rp 26.8 trillion in 2003 (though in reality most of the foreign interest burden was rescheduled in 2002 and 2003). As a proportion of revenue, external interest expenses have declined from 9.8% in 2001 to 8% in 2003, com-pared with 11% in the pre-crisis period. Despite the relative improvement in the debt service position, substantial challenges remain. Indonesia is entering the next phase of debt management, with the need to roll over maturing re-capitalisation bonds. In addition, prepa-rations need to be made for 2004, when the government must resume servicing the interest and principal on official debt.

The Paris Club

The Paris Club is an informal grouping of creditor countries. Its role is to assist debtor nations experiencing payment difficulties, through the rescheduling of official debt.

One of the principles under which the Paris Club operates is that of condition-ality: assistance is provided to countries that implement reforms to resolve their payment difficulties. In practice condi-tionality is provided by an IMF program

that demonstrates a need for debt relief (www.clubparis.org). The consequence of the Indonesian government’s decision to graduate from the IMF program at the end of 2003 is that further rescheduling of official debt will no longer be avail-able from 2004.

Indonesia has benefited from Paris Club rescheduling of principal since 1998, and of principal and interest in 2002 and 2003. Given that its official debt has been rescheduled at concessional rates of interest, there has in effect been a write-off of external public debt in net present value terms.

Debt Management

The original recapitalisation bonds were given relatively short maturities, in the expectation that IBRA asset recoveries would allow the government to redeem the majority of them. Given that most of the recapitalisation cost went on taking banks from negative to zero capital, and only a small proportion on restoring capital adequacy ratios to 4% (BI’s mini-mum adequacy standard for banks to continue in business), it was unrealistic to assume that the proceeds from any bank privatisations would recoup the value of recapitalisation bonds placed into the banks. In reality the bond issue was the cost of providing a blanket guar-antee to protect depositors.

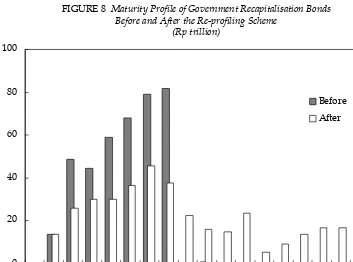

The maturity profile of the recapital-isation bonds is such that the govern-ment cannot repay them from the budget as they fall due. Under the origi-nal maturity structure, Rp 48.7 trillion of the bonds were scheduled to mature in 2004, and a further Rp 44.4 trillion in 2005. The only option open to the gov-ernment was to roll these bonds over (i.e. to issue replacement bonds) as they matured. However, the absence of a dy-namic domestic bond market10 made it

unlikely that the domestic market could be developed sufficiently to cope with

the value of maturing debt. As reported by Alisjahbana and Manning (2002: 289), the government opted to ‘re-profile’ some of the bonds held by the state banks, in order to smooth the maturity profile of the debt.

On 20 November, after receiving agreement from the parliament, the gov-ernment offered the state banks an exchange program in which bonds ma-turing in the period 2004–09 could be swapped for new bonds maturing be-tween 2010 and 2020. The new bonds consisted of fixed rate bonds for the pe-riod 2010–13 and variable rate bonds for the period 2014–20. In order to preserve the integrity of the bond market and not undermine the future profitability of the state banks, the new bonds were issued on a net present value (NPV) neutral basis.11 Because the fixed rate

recapital-isation bonds had a below-market inter-est rate, extending their maturity profile

at the same market interest rate would have resulted in a reduced NPV of the bonds. This reduction would have been recorded as a loss in the individual bank’s accounts. Where the bank held the bonds in its trading account, no im-mediate loss would be recorded. How-ever, the bank’s future profitability would be reduced in either case.

Under the program, Rp 171.8 trillion of the Rp 231.6 trillion of bonds held by state banks were re-profiled, at an additional cost to revenue of Rp 767.7 billion or 0.45% on the re-profiled bonds. Figure 8 shows the maturity profile of the bonds before and after re-profiling.

The profile shown in figure 8 excludes hedge bonds that are due to mature. However, under the terms of issue for hedge bonds, the government has the discretion either to pay out maturing bonds or to roll them over as variable

FIGURE 8 Maturity Profile of Government Recapitalisation Bonds Before and After the Re-profiling Scheme

(Rp trillion)

Source: Ministry of Finance. 0

20 40 60 80 100

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020

Before

After

bonds. It is considered likely to roll them over to 2010 and beyond.

Despite the re-profiling, the govern-ment is still left with a sizeable jump in the debt maturity profile from 2004, the year it must resume servicing its foreign obligations.

The task is not as insurmountable as it may at first seem, however. The long awaited domestic bond law was passed by the parliament in September 2002. Following its passage, the Ministry of Finance launched the first Treasury bond auction of Rp 2 trillion in December 2002. Under the sale system, bonds were sold through primary dealers rather than at a fully open auction, with an estimated yield to maturity in the range of 14.5–15%. The actual offer was 3.5 times oversubscribed, with bids of less than 14.7% accepted. The bonds were issued with a coupon interest rate of 14.5%.12

The Ministry of Finance plans a bond issuance program of around Rp 8 tril-lion for 2003; this should easily be achievable, given the success of the in-augural issue. In addition, the govern-ment intends to use the realisations from IBRA asset sales—in excess of what is needed to fund the budget—to repur-chase bonds from the market. Given that IBRA’s 2002 recoveries were well in ex-cess of the budget funding task, the bal-ance is available for repurchase of recapitalisation bonds through the mar-ket. This money, if directed to repur-chasing bonds maturing in 2004 and 2005, should ease the liquidity burden on the rollover of domestic bonds.

The issue that still has to be resolved is how the government will deal with the interest servicing cost and maturity of external borrowings. Although the interest servicing cost of external debt is now below pre-crisis levels when measured as a percentage of revenue, there will nevertheless be a $3 billion (Rp 27 trillion) jump in the interest and

principal servicing cost of external debt in 2004 (Rieffel 2002).

Options open to the government to fi-nance its external debt are limited, but it is not an impossible task. The budget should be approaching a balanced po-sition, provided the government is able to maintain progress on fiscal consoli-dation. The fiscal position should also be enhanced by declining nominal in-terest rates, as long as BI is able to re-duce the level of inflation. On the downside are increasing parliamentary antipathy to raising funds from asset sales and privatisation, and pre-election pressure for increased expenditure and taxation concessions.

When IBRA is wound up at the end of 2003, the remaining assets are likely to be transferred to the Ministry of Fi-nance; however, the ministry’s asset re-covery powers are less than those of IBRA (although IBRA powers were not fully utilised). It is not clear that the Ministry of Finance will be in a position actively to pursue recovery, and in any case the loans are likely to be of limited value by the time they are transferred.

The government has announced an ambitious program of privatisation for 2003. The privatisation road has been a rocky one to date, with the government achieving limited success amid increas-ing political opposition. The number of ‘easy’ sales (those of minority interests in companies already listed on the stock exchange) will diminish, and it is diffi-cult to see the government being able to push through sensitive sales as the elec-tion looms closer.

In the past, development spending has borne the brunt of government ex-penditure cutbacks made to meet fiscal targets, but the election year will make that more difficult; indeed, the pressure will be on the government to increase expenditures. The alternative is to in-crease revenues through more efficient

and equitable taxation collection. The recently established Large Taxpayer Of-fice is a promising start. The ofOf-fice aims to improve taxation administration and compliance through faster processing with increased transparency. However, this initiative needs to be spread to all levels of taxation assessment and collec-tion so as not to distort investment deci-sions.

Graduation from the IMF program on an amicable basis raises the possibility of the government raising capital in inter-national bond markets. Alternatively, it may wish to raise the funds domestically and purchase the foreign exchange in the market, although this may have adverse implications for the currency.

Bilateral raisings and increased bor-rowings from the development banks again represent a possibility, but

in-creased borrowing from the World Bank is dependent on Indonesia satis-fying the criteria for the Bank’s high lending scenario.13 Indonesia has not

been able to satisfy these criteria in the past two years.

The decision in January to wind back the administered price increases neces-sary to eliminate subsidies from the budget will reduce the government’s flexibility even further. It is clear, how-ever, that meeting Indonesia’s external obligations will necessarily involve contributions from all sources. Indeed, the need to deal with external liabilities, while at the same time meeting the po-litical imperative of graduation from the IMF program, will necessitate adherence to sound economic policies.

9 February 2003

NOTES

1 Not all of the decline in net reserves would have been the result of interven-tion: a part would have been due to offi-cial transactions.

2 Care needs to be taken when analysing GDP by expenditure. Because it is mea-sured on a residual basis, the estimate for stocks includes a statistical discrepancy that can exaggerate the importance of stocks as a component of GDP.

3 Malaysian Shipowners Association, www.malaysianshipowners.org. 4 Each month the international economic

survey organisation Consensus Econom-ics polls over 130 Asia Pacific economic forecasters for their estimates of a range of variables, including GDP. The results are then published as Asia Pacific Consen-sus Forecasts.

5 For a discussion of the objectives of mon-etary policy, see Grenville (2000). 6 See Alisjahbana and Manning (2002:

296–7) for a discussion of problems of in-vestment in the electricity sector. 7 Bank Niaga and Bank Danamon are

pri-vate sector banks acquired by the gov-ernment as part of the recapitalisation

process. Bank Mandiri is a state bank formed in 1999 from the merger of four state banks.

8 Conglomerates were not technically bailed out: the recapitalisation of the pri-vate banks saw owners’ shareholdings diminish, corporate debts were not ex-tinguished but transferred to IBRA, and bank owners were required to pledge additional assets where their banks exceeded the prudential limits on con-nected lending (i.e. through bank share-holder settlement agreements). The bail-out of conglomerates comes from IBRA’s failure to pursue vigorously the repayment of debts, and not from the re-capitalisation per se.

9 The World Bank (2000) estimated that the ratio of debt to GDP would not decline to 80% until 2006.

10 Prior to the financial crisis, the Indone-sian government had always financed the budget deficit externally through official development assistance (ODA). 11 ‘NPV neutral’ means the present value

of the bonds to be replaced equals the present value of the replacement bonds.

12 BI website: Investor Information and Enquiries, ‘Government of Indonesia issued Rupiah Currency Bond Serial FR 0021’ (http://www.bi.go.id/iie/), 24/12/2002.

13 The World Bank at recent CGI meetings has indicated two amounts that it is

pre-pared to lend to Indonesia: a base case lending scenario and a high case lending scenario which is dependent on the gov-ernment meeting certain structural benchmarks. Indonesia has not qualified for the high case lending scenario in re-cent years.

REFERENCES

Alisjahbana, Armida S., and Chris Manning (2002), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 38 (3): 277–305.

Bappenas (National Planning Agency) (2003), ‘Indonesian Economy in the Year 2003: Prospects and Policies’, Jakarta, January.

DRI (Danareksa Research Institute) (2002), Consumer Confidence, Jakarta, December (mimeo).

Grenville, Stephen (2000), ‘Monetary Policy and the Exchange Rate during the Crisis’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (2): 43–60.

IMF (2002), Indonesia: Selected Issues, Coun-try Report No. 02/154, published 29 July 2002 (but dated 12 April 2002) at: http:// www.imf.org/external/country/IDN/ index.htm.

James, William E., David J. Ray and Peter J. Minor (2003), ‘Indonesia’s Textiles and Apparel: The Challenge Ahead’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 39 (1), in this issue.

Johnson, Colin (1998), ‘Survey of Recent De-velopments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Eco-nomic Studies 34 (2): 3–60.

Rieffel, Lex (2002), ‘The Coming Crunch in 2004’, Usindo Brief, 7 November, http:// usindo.org/pu2002briefs.htm.

Sabirin, Syahril (2003), To Realize Hope, To Answer Challenges, Address by the Gov-ernor of BI to the Annual Bankers’ Meet-ing, Jakarta, http://www.bi.go.id. World Bank (2000), Managing Government

Debt and Its Risks, Washington DC, 22 May.

World Bank (2002a), East Asia Update, Making Progress in Uncertain Times, Washington DC, November, http:// lnweb18.worldbank.org/eap/eap.nsf/ Attachments/EAP+Regional+Update/ $File/EAP+Regional+Update.pdf. World Bank (2002b), Indonesia:

Maintain-ing Stability, DeepenMaintain-ing Reforms, World Bank Brief for the Consultative Group on Indonesia, Jakarta, http:// lnweb18.worldbank.org/eap/eap.nsf/ Attachments/011603_12CGIBrief/$File/ 011603_12CGIBrief.pdf

World Bank (2003), Confronting Crisis: Impacts and Response to the Bali Tragedy, Jakarta, January, http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/ eap/eap.nsf/Attachments/012103-12CGI-Bali/$File/CGI_BaliUpdate.pdf.

In the April 1999 issue the Indonesia Project announced the introduction of a special prize intended to encourage Indonesian scholars to publish their work in the Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies.

The H.W. Arndt Prize, named in honour of the founding Editor of BIES, is awarded for the best article by one or more Indonesian authors published by BIES in each calendar year.

The competition is open to all Indonesian citizens who are not members of the Editorial Board or International Advisory Board of BIES, and is adjudicated by a panel appointed by the Editor.

Winners are invited to visit the Indonesia Project for a period of four weeks, during which time they have the opportunity to further their research and to present at least one seminar in the Economics Division of the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies (RSPAS) at The Australian National University. The prize includes a round trip economy air fare between Jakarta and Canberra, plus a living allowance for the duration of the visit.

Articles with joint authorship by more than one Indonesian citizen are eligible for consideration, but the prize will be awarded to only one of the authors. In such cases, the authors will need to nominate one person as the potential recipient of the prize, prior to the adjudication process.

The regular Survey of Recent Developments, and articles with a non-Indonesian citizen as a joint author, are not eligible for award of the H.W. Arndt Prize. The Indonesia Project retains the right not to award the prize in any year if no entry is considered by the adjudication panel to be of sufficiently high quality.

SUPPLEMENTARY SCHOLARSHIPS

The Indonesia Project in the Economics Division, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies (RSPAS), at The Australian National University wishes to encourage research at PhD level on the Indonesian economy and, in the longer term, to expand the number of young Australians and New Zealanders with a close familiarity with Indonesia and its economy.

To this end, current or prospective PhD scholars at The Australian Na-tional University who are interested in undertaking doctoral research on any aspect of the Indonesian economy are invited to apply for special Supplemen-tary Scholarships, in the amount of $8,500 per annum for up to three and a half years. These Scholarships are to be known as the H.W. Arndt Supplementary Scholarships, in honour of the founder of the Indonesia Project, the late Pro-fessor H.W. Arndt. Applicants should hold, or have been offered, a PhD sti-pend scholarship such as an Australian Postgraduate Award, an ANU PhD Scholarship, or an ANU Graduate School Scholarship.

Successful applicants will be subject to the normal requirements for comple-tion of the ANU PhD in Economics, details of which may be found at http:// www.anu.edu.au/graduate/programs_courses/programs. In addition, they will be expected to spend three to nine months undertaking fieldwork in Indo-nesia for the purpose of collecting data and other information for their doc-toral project, and to have, or to acquire, basic fluency in the Indonesian language to assist in this work. They will be located in the Economics Division, RSPAS, where they will be able to draw on the resources of the Division and the Indo-nesia Project for supervisory and other needs.

Continued payment of the Supplementary Scholarship in each successive year will be subject to satisfactory performance. Applicants must be Austra-lian or New Zealand citizens or permanent residents.

Persons wishing to apply for the H.W. Arndt Supplementary Scholarships should notify the Head of the Indonesia Project at the time they apply for PhD scholarships tenable at the ANU, or as soon as practicable thereafter, enclos-ing a copy of the application, at the followenclos-ing address:

Head, Indonesia Project Division of Economics

Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University

Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia

Fax: +61 2 6125 3700

Email: Chris.Manning@anu.edu.au