CLINICAL AND

ORGANIZATIONAL APPLICATIONS

OF APPLIED

BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS

CLINICAL AND

ORGANIZATIONAL APPLICATIONS

OF APPLIED

BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS

Edited by

HENRY S. ROANE

Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York, USA

JOEL L. RINGDAHL

Rehabilitation Institute, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA

TERRY S. FALCOMATA

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA

AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO

Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier

525 B Street, Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101-4495, USA 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA

The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, UK First published 2015

Copyright©2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangement with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website:www.elsevier.com/permissions

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN: 978-0-12-420249-8

For information on all Academic Press publications visit our website atstore.elsevier.com

Printed and bound in the United States

Keith D. Allen

Department of Psychology, Munroe-Meyer Institute for Genetics and Rehabilitation, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

Scott P. Ardoin

Department of Educational Psychology and Instructional Technology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA

Jonathan C. Baker

Rehabilitation Institute, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA Yvonne Barnes-Holmes

Department of Psychology, National University of Ireland Maynooth, Co., Kildare, Ireland Breanne J. Byiers

Department of Educational Psychology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA

Jacob H. Daar

Rehabilitation Institute, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA Jesse Dallery

Department of Psychology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA Edward J. Daly III

Department of Educational Psychology, University of Nebraska Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

Erica Dashow

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Douglass Developmental Disabilities Center, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

Anthony Defulio

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Mark R. Dixon

Rehabilitation Institute, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA Kathleen M. Fairchild

Rehabilitation Institute, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA Terry S. Falcomata

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA Wayne W. Fisher

Center for Autism Spectrum Disorders, Munroe-Meyer Institute, The University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

xiii

Dana M. Gadaire

The Scott Center for Autism Treatment and Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Florida, USA

Cindy Gevarter

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA Heather K. Gonzales

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA Nicole L. Hausman

Department of Behavioral Psychology, The Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Jeffrey F. Hine

Department of Psychology, Munroe-Meyer Institute for Genetics and Rehabilitation, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

David C. Houghton

Department of Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA Robert W. Isenhower

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Douglass Developmental Disabilities Center, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

SungWoo Kahng

Department of Health Psychology, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA

Michael E. Kelley

The Scott Center for Autism Treatment and Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Florida, USA

Michelle Kuhn

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA Giulio E. Lancioni

Department of Education, University of Bari, Bari, Italy

Russell Lang

Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas, USA Robert H. LaRue

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Douglass Developmental Disabilities Center, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

Linda A. LeBlanc

Trumpet Behavioral Health, Lakewood, Colorado, USA

Dorothea C. Lerman

Department of Clinical, Health, and Applied Sciences, University of Houston—Clear Lake, Houston, Texas, USA

Clare J. Liddon

The Scott Center for Autism Treatment and Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Florida, USA

Timothy D. Ludwig

Department of Psychology, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina, USA James K. Luiselli

Clinical Solutions, Inc. and North East Educational and Developmental Support Center, Tewksbury, Massachusetts, USA

Brian K. Martens

Department of Psychology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA

Monica M. Matthieu

School of Social Work, St Louis University, St Louis, Missouri, USA

Ciara McEnteggart

Department of Psychology, National University of Ireland Maynooth, Co., Kildare, Ireland

Heather M. McGee

Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo Michigan, USA Steven E. Meredith

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Suzanne M. Milnes

University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Munroe-Meyer Institute, Omaha, Nebraska, USA Raymond G. Miltenberger

Department of Child and Family Studies, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, USA

Matthew P. Normand

Department of Psychology, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California, USA Triton Ong

Department of Psychology, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California, USA Mark F. O’Reilly

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA Kerri P. Peters

Psychology Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA Cathleen C. Piazza

University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Munroe-Meyer Institute, Omaha, Nebraska, USA Derek D. Reed

Department of Applied Behavioral Science, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA

Joe E. Reichle

Department of Educational Psychology, and Department of Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA

Aurelia Ribeiro

The Scott Center for Autism Treatment and Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Florida, USA

Laura Rojeski

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA Patrick W. Romani

Munroe-Meyer Institute, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA Nicolette Sammarco

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA

Sindy Sanchez

Department of Child and Family Studies, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, USA

Kelly M. Schieltz

College of Education, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA Dawn A. Seefeldt

Rehabilitation Institute, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA Rebecca A. Shalev

University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Munroe-Meyer Institute, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

Jeff Sigafoos

Department of Special Education, Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand Sigurdur O. Sigurdsson

School of Behavior Analysis, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Florida, USA Sarah K. Slocum

Psychology Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA Kimberly N. Sloman

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Douglass Developmental Disabilities Center, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

Diego A. Valbuena

Department of Child and Family Studies, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, USA

Amber L. Valentino

Trumpet Behavioral Health, Lakewood, Colorado, USA Timothy R. Vollmer

Psychology Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

David P. Wacker

Center for Disabilities and Development, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA Laci Watkins

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA David A. Wilder

School of Behavior Analysis, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Florida, USA Alyssa N. Wilson

School of Social Work, St Louis University, St Louis, Missouri, USA Douglas W. Woods

Department of Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA Amanda N. Zangrillo

Center for Autism Spectrum Disorders, Munroe-Meyer Institute, The University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

The origin of this text arose from countless conversations with other pro- fessionals who generally reported, “I know about applied behavior analysis.

I’ve seen it done before.” Undoubtedly, many of those professionals had seen a version of applied behavior analysis (or “ABA” as it is often referred to) conducted with their child, student, or patient; however, it became clear that others held a relatively restricted notion of ABA. Without doubt, one of the most notable utilizations of ABA has been within the context of the interventions relating to skill deficits and behaviors of excess displayed by individuals with developmental disabilities, specifically autism. Although numerous procedures and approaches have been presented as potential treat- ments for the behavioral symptoms of autism, those based on the principles of ABA have received the most empirical support. As a result, in recent years, the term “applied behavior analysis” appears to be used quite often as a synonym for a very specific range of interventions for autism.

Many readers would note that ABA is but a subfield of the broader area of behavior analysis that also includes: (a) behaviorism, which focuses on the world view, theory, or philosophy of behavior analysis, and (b) the experimental analysis of behavior (EAB), which focuses on identifying and analyzing the basic principles, mechanisms, and processes that explain behavior. ABA is distinct from EAB in that it is considered a clinical disci- pline in which the general principles of learning and behavior are applied for the purpose of addressing socially relevant problems and issues. Thus, behav- ior analysts who work in ABA conduct research that assists in developing and evaluating evidence-based practices directed toward the remedy of problems associated with socially significant behavior. Applied behavior analysts then use the results of the applied research to create and implement effective evidence-based procedures in more natural settings such as schools, homes, and the community. Such work often focuses on behavioral problems that occur in particular settings, are associated with particular populations (e.g., individuals with autism or other developmental disabilities), and those that are present within larger social contexts (e.g., organizational behavior management).

In light of the efficacy of ABA-based procedures in addressing behaviors associated with autism, it is important to note that the principles underlying this therapeutic approach have been shown to be similarly effective when

xix

applied to other populations, settings, and behaviors. The current text pro- vides a review of such clinical applications toward the purpose of expanding the reader’s knowledge related to the breadth of ABA-based applications.

Simply put, the goal is to illustrate the use of ABA beyond the realm of autism.

The content of this book was identified from an informal survey of ABA practitioners and researchers on their knowledge of current areas of clinical practice. In general, an attempt was made to limit the proposed content to clinical applications which have been divided into four broad areas: child applications, adult applications, broad-based health applications, and appli- cations in the area of organizational behavior management. Undoubtedly, as the field continues to expand its breadth, there are some areas in which ABA methods are applied to novel areas of study that may have been omitted from inclusion.

The editors have drawn upon a range of subject-matter experts who have clinical and research experience in the application of ABA across multiple applications to serve as contributors to this volume. A great deal of thought was expended in determining whom we should contact for material on a given chapter. In many cases, the decision was difficult as there are a number of subject-matter experts who would have been appropriate. In the majority of cases, our initial approach to a potential contributor was met with an enthusiastic acceptance. Consequently, the resulting text includes contribu- tions from individuals who have served as editors, associate editors, or edi- torial board members for prominent content-area journals such as theJournal of Applied Behavior Analysis, theJournal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, theJournal of Organizational Behavior Management, and theBehavior Analyst.

This book is best suited as a primary textbook for coursework in behavior analysis, psychology, or education. Also, while practitioners and students are the ultimate targets of this work, other professionals should find the content and language to be manageable. The hope is that this volume will be infor- mative in demonstrating the range of application of ABA to various prob- lems of social significance. We hope the reader finds this book as enjoyable as it was to edit.

Henry S. Roane Joel E. Ringdahl Terry S. Falcomata

Defining Features of Applied Behavior Analysis

Terry S. Falcomata

Department of Special Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA

INTRODUCTION

Individuals who work in applied behavior analysis (ABA) implement clinical interventions as well as conduct research to assist in the development of prac- tices for addressing problems that occur with socially significant behavior.

Applied behavior analysts often conduct applied research and use the results to create and implement effective, evidence-based procedures in more natural settings such as the home, schools, and the community. ABA-based research often focuses on behavioral issues that occur in specific settings, are associated with particular populations including children (e.g., obesity, autism or other developmental disabilities, traumatic brain injury, feeding disorders) and adults (e.g., caregiver training, sports performance, gambling), as well as those within other social contexts such as various workplace environments (e.g., perfor- mance management, workplace safety, systems analysis).

Although ABA has an extensive history of effectiveness in application and research across a diverse number of areas of focus, settings, and popula- tions, perceptions exist in the media, various disciplines, and the public in general that ABA is synonymous with procedures for addressing issues related to autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities (e.g., discrete-trial training and other procedures to promote skill acquisi- tion; functional behavioral assessment and treatment of challenging behav- ior). In fact, the use of ABA-based methods and procedures to address issues relating to autism is just one of the many examples of the effective applica- tion of the ABA approach to addressing socially significant behavior. Said another way, although ABA has been demonstrated to be an effective approach to addressing issues with autism (e.g.,Howard, Stanislaw, Green, Sparkman, & Cohen, 2014; MacDonald, Parry-Cruwys, Dupere, & Ahearn, 2014; Matson, Tureck, Turygin, Beighley, & Rieske, 2012), this aspect of ABA represents only one, relatively narrow application.

Clinical and Organizational Applications of Applied Behavior Analysis ©2015 Elsevier Inc. 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-420249-8.00001-0 All rights reserved.

This chapter provides an overview of the features of ABA within the framework provided byBaer, Wolf, and Risley (1968)and how those fea- tures characterize work conducted in various areas of focus, settings, and populations. Each of the dimensions is described and demonstrated using examples from various child, adult, and organizational ABA-based research.

DIMENSIONS OF ABA

Baer et al. (1968)provided what they contended were defining dimensions of ABA. As described by Baer et al., there are seven dimensions of ABA that must be present to ensure that effective practices are developed and implemented. According to Baer et al., ABA is (a) applied, (b) behavioral, (c) analytic, (d) technological, (e) conceptually systematic, (f) effective, and (g) generalizable. The remainder of this chapter will review the dimensions described by Baer et al. using applied studies across various populations and areas of focus as outlined in this text to illustrate how they characterize ABA.

Applied

The termappliedindicates that a particular target behavior of interest is of social significance. Further, it is the emphasis on social significance that dis- tinguishes ABA from laboratory analysis. Specifically, applied behavior ana- lysts select behaviors that are socially meaningful and are currently of importance to the individual(s) whose behavior is being addressed. At var- ious times, applied behavior analysts have opportunities to address numerous behaviors demonstrated by individuals, and it is considered vital that they prioritize those behaviors in terms of importance. Illustrations of theapplied dimension of ABA are wide-ranging and can be observed in studies across numerous populations, settings, and areas.

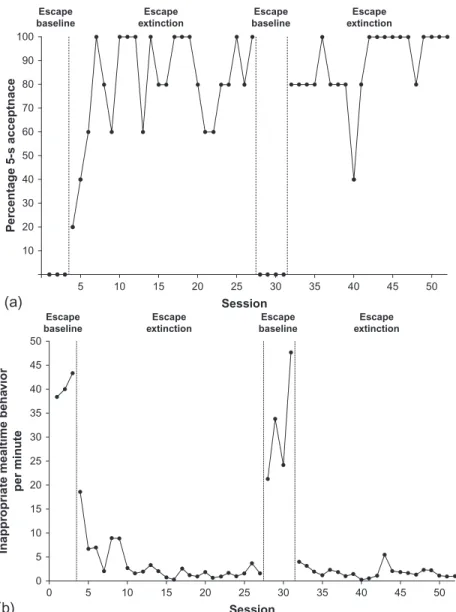

Myriad child-focused studies have been conducted within ABA that exemplify the focus on social significance. These include (but are not limited to) studies evaluating treatments for feeding disorders (e.g.,Kadey, Piazza, Rivas, & Zeleny, 2013; Kadey, Roane, Diaz, & Merrow, 2013; LaRue et al., 2011; Volkert, Vaz, Piazza, Frese, & Barnett, 2011), interventions for childhood obesity (e.g., Fogel, Miltenberger, Graves, & Koehler, 2010; Van Camp & Hayes, 2012), and issues relating to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; e.g.,Northup, Fusilier, Swanson, Roane,

& Borrero, 1997; Ridgway, Northup, Pellegrin, LaRue, & Hightsoe, 2003).

The ABA-based approach to the assessment and treatment of pediatric feeding disorders has included a wide variety of behaviors of significant social

importance including food refusal (Borrero, Woods, Borrero, Masler, &

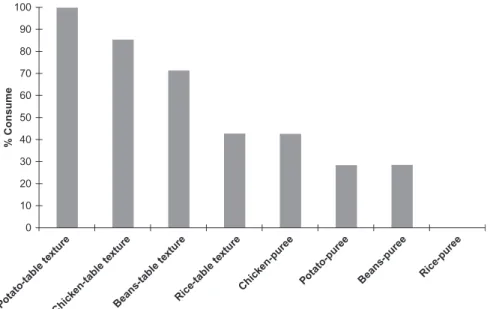

Lesser, 2010), self-feeding (Vaz, Volkert, & Piazza, 2011), and swallowing (e.g.,Kadey, Piazza, et al., 2013). For example,Kadey, Piazza, et al. (2013) addressed the food consumption of a 5-year-old girl who relied on a gastro- stomy tube for her caloric needs. The authors conducted a texture assess- ment in which they evaluated various textures, across foods, to determine the one which the girl could successfully swallow. Through their systematic process of identifying a texture with which she could be successful with indi- vidual foods, the authors were able to increase the girl’s consumption of those foods.

Child obesity is another socially significant area in which several ABA- based studies have been conducted.Fogel et al. (2010)evaluated the effects of video game-based exercise (i.e., exergaming) relative to traditional phys- ical education (PE) with four physically inactive and overweight fifth grade students. The authors’ purpose was to evaluate whether the physical activity of the children would increase through exposure to 10 exergames (e.g., Play Station; Nintendo Wii Boxing, Sports Baseball, Sports Tennis; iTech Fitness XrBoard). Through the use of the exergaming approach, the authors were able to substantially increase the physical activity of all four children above the levels observed during traditional PE.

A third socially significant, child-focused area of study deals with vari- ables relating to ADHD.Northup et al. (1997)evaluated the effects of stim- ulant medication on five children with ADHD diagnoses. Specifically, the authors evaluated the children’s preference for different reinforcers (quiet time, alone play, and social play) across the presence and absence of stimulant medications. Although the results of Northup et al. were idiosyncratic across children, the authors showed that stimulant medication can alter children’s motivation for types of reinforcement.

Studies conducted in the areas of pediatric feeding disorders such as Kadey, Piazza, et al. (2013), childhood obesity such asFogel et al. (2010), and ADHD such as LaRue et al. (2011) illustrate the emphasis of child- focused ABA on social significance. Each of the dependent variables, or tar- get behaviors, in the above studies was meaningful and of practical impor- tance to the children in the studies and to potential future consumers of the studies.

Similarly, a large number of adult-focused studies with high social signif- icance have been conducted within ABA. These include (but are not limited to) studies evaluating assessment, treatment, and training practices in path- ological gambling (e.g.,Guercio, Johnson, & Dixon, 2012; Nastally, Dixon,

& Jackson, 2010) as well as teacher and caregiver training (e.g., Lerman,

Tetreault, Hovanetz, Strobel, & Garro, 2008; Lerman, Vorndran, Addison,

& Kuhn, 2004).

For example, the dimension of social significance is demonstrated in adult-focused, ABA-based studies pertaining to the assessment, treatment, and determination of the variables that contribute to pathological gambling.

Guercio et al. (2012)studied a treatment intended to decrease urges to gam- ble and actual gambling behavior of three adults with acquired brain injury who were also indicated as pathological gamblers. The authors implemented a treatment program that consisted of one-on-one therapy that entailed pro- viding instruction to the adults about motivating operations (MOs), ante- cedents, and consequences relating to gambling. Through the application of the treatment program, the authors demonstrated a reduction in urges to gamble (based on data collected via self-reports) and gambling behavior in each of the adults.

Another adult-focused area of study that illustrates the dimension of social significance in ABA is care provider training. Lerman et al. (2008) evaluated a training program intended to teach skills to teachers of children with autism relating to the implementation of preference assessment and teaching procedures. The training program consisted of a variety of teaching methods including lectures, discussion, and role-play procedures. The results showed that the training program resulted in the acquisition of the target skills by each of the teachers, and follow-up assessment suggested that those skills maintained over time following training. Similar to the child- based studies described above, each of the dependent variables evaluated in adult-based studies was meaningful and of obvious practical importance.

Many studies have also been conducted in the area of organizational behavior management (OBM) pertaining to safety (e.g.,Ludwig & Geller, 1997) illustrating the applied nature of ABA. For example, Ludwig and Geller (1997)conducted a study in which they evaluated an intervention aimed at increasing safe driving behavior of pizza delivery drivers. Specifically, the authors implemented two interventions with two groups of drivers, respectively. One intervention consisted of goal setting in which the drivers participated in the setting of the goals. The second intervention consisted of goal setting but the drivers did not participate in the setting of goals. The results showed that both interventions were effective at increasing complete stops at intersections. Further, the results also showed that nontargeted safe driving behaviors (i.e., turn signal use, safety belt use) also increased during one of the interventions. The interventions, which were antecedent-based in nature, utilized byLudwig and Geller (1997)demonstrated the effective

use of an ABA-based approach to produce positive, socially significant changes with meaningful and practical target behaviors.

Behavioral

The term behavioral indicates that ABA concerns itself with the study of directly observable behavior. Specifically, applied behavior analysts empha- size the direct observation and manipulation of overt behavior. Indirect measures of behavior such as self-report, interviews, or checklists, although often used, are de-emphasized in ABA research in favor of direct methods of measurement and manipulation. In addition, applied behavior analysts do not attribute behavior as characteristics of, or based upon, nonbehavioral constructs or inner qualities (e.g., personality traits). Rather, ABA empha- sizes the manipulation of environmental variables and the observation of relations between behaviors of interest and those variables for the purpose of demonstrating functional relations (i.e., functions of behavior). The behavioral dimension of ABA is vital because of the importance of precise measurements of behaviors of interest that, in turn, allow for valid evalua- tions and demonstrations of functional relations between interventions of interest and target behaviors of importance (see Section “Analytic”). Fur- ther, it allows for a systematic analysis of the extent to which applied behav- ior analysts are addressing the intended target behaviors and not approximations or nontarget behaviors (i.e., reliability of measurement).

Thebehavioraldimension of ABA can be illustrated in numerous child- based studies including those focusing on challenging behavior (e.g.,Athens

& Vollmer, 2010; Lustig et al., 2014) and academic skills (e.g., Martens, Werder, Hier, & Koenig, 2013). For example, Athens and Vollmer (2010)conducted a study in which they evaluated a treatment of challenging behavior exhibited by children with autism and ADHD. The authors focused exclusively on the direct observation of the target behaviors (i.e., aggression, disruption, compliance, communicative behaviors). To do so, the authors established a specific, operational definition of aggression for the participant (Henry) that consisted of “forcefully hitting and kicking others resulting in bruising his victims” (p. 573). This definition allowed for the direct observation and measurement of the presence and absence of the behavior. This approach can be contrasted with a nonbehavioral approach that might consist of anecdotal reports, or impressions provided by care providers regarding the behavior of the child.

Martens et al. (2013)focused on accuracy and fluency exhibited by chil- dren during oral reading. The authors specifically defined each of these target

behaviors to allow for direct observation and measurement. Specifically, they established an operational definition of accuracy that consisted of the correct reading of a particular word, and they established an operational definition of fluency that consisted of the number of words correctly read per minute.

Establishing these specific, observable operational definitions allowed the authors to evaluate variables (i.e., an intervention consisting of word training) impacting their occurrence, or lack thereof, in a systematic way. Without an emphasis on a behavioral approach, establishment of reliability of measure- ment would not be possible which would have precluded the authors from drawing conclusions about relations between their independent and depen- dent variables (i.e., conclusions about the effectiveness of their interventions would not be appropriate in the absence of demonstration of reliability of measurement made possible by the behavioral approach).

Thebehavioral dimension of ABA is also illustrated in numerous adult- based studies including those focusing on problem behaviors in gerontolog- ical populations (e.g.,Baker, LeBlanc, Raetz, & Hilton, 2011) and acquired brain injury (e.g.,Lancioni et al., 2012). For example, Baker et al. (2011) intervened with an individual with Alzheimer’s-type severe dementia who was engaging in hoarding behaviors. The authors established a defini- tion of hoarding that allowed for the direct observation and measurement of the behavior (i.e., putting items in her shirt or pants). This was opposed to a nonbehavioral approach that might have relied on the feelings of the staff that worked with her. Thus, by relying on directly observable behaviors, the authors minimized potential bias and accuracy issues that would likely impact nonbehavioral approaches (e.g., staff impressions). Subsequently, the authors were able to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of two interventions and demonstrate their effectiveness. In another adult-focused study, Lancioni et al. focused on text messaging skills with individuals with acquired brain injuries. To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of their intervention, the authors established operational definitions that allowed for the direct observation and measurement of target skills related to text mes- saging including number of messages sent, length of messages, the time needed to send and receive messages, and number of messages received and whether the individual read/listened to the message. Whereas this approach allowed for a systematic, empirical evaluation of the effects of the intervention, a nonbehavioral approach would not have allowed for a precise and accurate reflection of positive (or lack thereof) effects.

Many studies that illustrate thebehavioralapproach of ABA have also been conducted in the area of OBM pertaining to performance management

(e.g., Fienup, Luiselli, Joy, Smyth, & Stein, 2013; Goomas, Smith, &

Ludwig, 2011). For example,Fienup et al. (2013)evaluated an intervention intended to improve the performance of staff at a human services organiza- tion. Specifically, the authors intervened with the purpose of decreasing staff tardiness for supervision meetings. The authors measured latency from the scheduled beginning time for meetings until the actual time in which meet- ings began. This behavioral and observable measurement system minimized potential inaccurate inferences about the positive effects of the intervention they employed. Goomas et al. (2011) focused on the performance of employees at a retail distribution center. The authors directly measured the amount of time it took employees to complete specific tasks. By estab- lishing direct measures of behavior, these authors were able to directly eval- uate potential relations between their intervention and its effects on those targeted behaviors.

Analytic

The termanalyticindicates that ABA emphasizes believable demonstrations of relations between behaviors of interest and environmental variables, interventions, and treatments under study. Systematic analysesof behavior are vital for the demonstration of experimental control with regard to the effects of independent variables (e.g., interventions and treatments) on dependent variables (e.g., socially relevant behaviors of interest). An empha- sis is placed on the analytic nature of ABA because it is vital that applied behavior analysts base their practical recommendations on “believable dem- onstrations” (Baer et al., 1968, p. 93) that their interventions were respon- sible for positive changes in behaviors of interest. Thus, it is important that the inferences about causal relations between recommended interventions and positive outcomes should be based on systematic, empirical methods and demonstrations of experimental control.

Experimental control is achieved when an applied behavior analyst dem- onstrates a functional, or causal, relation between environmental variables of interest and behaviors of interest. In ABA, various single-subject experimen- tal designs are utilized to demonstrate functional relations including (but not limited to) the reversal, multielement (and alternating treatments design), changing criterion, and multiple-baseline experimental designs. These basic designs share three common elements: (a) prediction—anticipated future levels of behavior, (b) verification—demonstration that the previously predicted levels of behavior would continue in the absence of a treatment, and (c) replication—repeating previous changes in behavior via the

reintroduction and subsequent removal of the treatment across time, set- tings, and/or individuals.

Theanalysisdimension of ABA is illustrated in the child-based literature as reflected by emphasis on, and use of, various single-subject experimental designs to demonstrate functional relations between the independent variables (e.g., environmental variables, interventions, treatments) and socially relevant behaviors of interest. For example, in the study described above,Kadey, Piazza, et al. (2013) employed a reversal design to systematically demonstrate the relation between swallowing behavior (i.e., mouth cleans) demonstrated by a 5-year-old girl with feeding problems and specific texture levels. Using the reversal design, the authors first implemented a smooth texture level produced by a specific type of food processer (i.e., a Magic Bullet®) and documented the percentage of bite trials in which the child swallowed as reflected by mouth cleans. The authors conducted repeated sessions in this initial condition, and the child demonstrated high and relatively stable levels of swallowing behavior.

The results of the first condition provided preliminary evidence of a relation between the child’s swallowing behavior and the texture level of the food.

However, without additional experimental manipulations, it would have been inappropriate to infer causality between food texture and swallowing. There- fore, the authors ended the condition and implemented a second condition in which pureed food was presented that was of a different texture than the food presented in the previous condition. The authors implemented repeated ses- sions in the second condition until they observed low and stable levels of swal- lowing. The results of the second condition provided additional evidence that the level of texture used in the first condition was responsible for the high levels of swallowing observed. However, the potential effects of extraneous variables on swallowing could not be ruled out (e.g., a variable outside of the evaluation may have coincided with the onset of the second condition and could have influenced the results). The authors reimplemented the initial condition and swallowing behavior increased back to levels observed during the initial con- dition. These results provided additional evidence that the high level swallow- ing resulted from the texture level rather than extraneous variables. The authors subsequently conducted an additional reversal (i.e., an additional puree condi- tion and additional Magic Bullet® condition) and produced similar results.

Thus, the co-occurrence of positive changes in the target behavior (i.e., swal- lowing) was demonstrated to occur only in the presence of the food texture produced by the Magic Bullet blender. Therefore, causality between positive effects observed with the swallowing behavior and the treatment could be rea- sonably inferred.

Normand (2008)provided an example of the use of a multiple-baseline (combined with an ABAB design), single-subject experimental design to demonstrate the functional relation between an intervention package and physical activity demonstrated by adults. Normand first introduced baseline conditions to each of four adult participants and measured the total number of steps taken by each participant. The treatment package (consisting of goal setting, self-monitoring, and feedback) was introduced with one of the par- ticipants after stable levels of steps taken were observed; while baseline con- tinued to be implemented with the other three participants. Positive effects (i.e., increased levels of steps taken) were observed with the first participant while concurrently, levels of steps taken continued at consistent levels with the additional four participants. This result provided preliminary evidence that the treatment package was effective at increasing steps taken; however, extraneous variables could not be ruled out without replication of those effects across participants. Therefore, Normand introduced the intervention with the second participant while baseline conditions continued with the other three participants. Similar patterns of behavior were observed with the second participant as those observed with the first participant with an increase in steps taken. These results represented a replication of the positive effects observed with the first participant. Coupled with the continued con- sistent levels of steps taken with the other two participants during baseline conditions, evidence accrued suggesting a functional relation between the treatment package and an increase in steps taken. Normand went on to rep- licate the positive effects with the additional two participants, demonstrating three replications of the initial positive effects. Through this process, the author was able to rule out, to a reasonable degree, the possible effects of extraneous variables on the observed positive effects. Said another way, through the demonstration of functional relations, Normand could be con- fident that it was the treatment package that produced the positive results and not some other extra experimental variable(s).

Empirical methods that emphasize the demonstration of functional relations are also emphasized in the area of OBM. For example,Pampino, MacDonald, Mullin, and Wilder (2004) used a multiple-baseline, single- subject design to evaluate the effects of an intervention package consisting of task clarification, goal setting, positive reinforcement, and feedback on completion of maintenance tasks by workers in a framing and art store.

The authors first collected baseline data prior to the implementation of the intervention package across two sets of duties. After stable levels of com- pletion of duties were observed across both sets of duties, the authors

implemented the intervention with one set of duties while continuing to collect baseline data with the second set of duties. Percentages of completion of the duties in the intervention condition immediately increased when the intervention was implemented, while levels of completion of the second set of duties (i.e., in baseline conditions) remained low. Next, the authors implemented the intervention with the second set of duties and an imme- diate increase in completion of those duties was observed; thus, the positive effects observed with the first set of duties were replicated with the second set of duties. The systematic methods used by the authors allowed them to infer causality between their intervention and the observed positive effects.

Technological

In addition to focusing on analysis and emphasizing functional relations through the use of appropriate experimental designs and the use ofbehavioral methods (e.g., precise measurements of target behaviors), ABA emphasizes thorough and accurate descriptions of procedures within the context of research and the application of behavioral interventions. Descriptions of procedures, operational definitions, and procedural integrity data are docu- mented to allow other applied behavior analysts to replicate studies and eval- uations in applied settings and research. A review of practically any study published in a peer-reviewed ABA journal (such as theJournal of Applied Behavior Analysis) will provide a demonstration of the technological aspect of ABA.

Conceptually Systematic

The practices utilized in ABA are applied in nature. However, there is a clear emphasis in ABA that these practices beconceptually systematic. Thus, basic behavioral principles empirically validated over many years by scientists and applied behavior analysts who conduct basic and applied research on the behavioral theories of experimental analysis of behavior underlie the practices of ABA. For example, intervention components that are based on conceptually systematic behavioral principles include (but are not limited to) reinforcement, extinction, punishment, stimulus control, discrimina- tion, MOs, and schedules of reinforcement.Baer et al. (1968)asserted that by emphasizing behavioral principles along with precise descriptions of pro- cedures, ABA would advance at a rate superior to an alternative approach that could be described as a “collection of tricks” (p. 96).

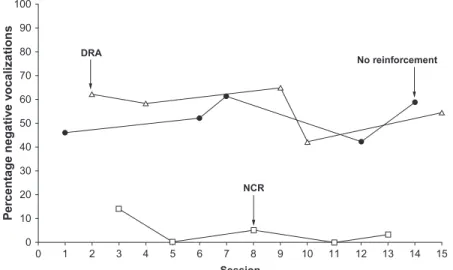

The emphasis on conceptual systems can be illustrated in the child-based behavioral literature pertaining to functional communication training (FCT;

Carr & Durand, 1985). FCT involves (a) evaluating and identifying the rein- forcer maintaining challenging behavior via a functional assessment (e.g., func- tional analysis; Carr & Durand, 1985; Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, &

Richman, 1982/1994); (b) training a new appropriate communicative behav- ior (e.g., card exchange, microswitch, sign language) and delivering the same reinforcer contingent on the response; (c) placing challenging behavior on extinction (i.e., reinforcement is withheld following occurrences of challeng- ing behavior; Fisher et al., 1993; Hagopian, Fisher, Sullivan, Acquisto, &

LeBlanc, 1998); and (d) in some cases, applying punishment contingent on challenging behavior (Hagopian et al., 1998; Wacker et al., 1990). Thus, the effectiveness of FCT is based on the behavioral mechanisms including rein- forcement (positive and/or negative) and, in many cases, extinction and pun- ishment, as well as training procedures such as the use of a time-delay prompt.

The approach of conceptualizing FCT using behavioral mechanisms and a conceptual system is distinct from a potential approach to the treatment that might focus on other aspects of the treatment. For example, a clinician focusing on FCT without considering the underlying conceptual system may favor conceptualizing the treatment as one that focuses on the utiliza- tion of technology (e.g., iPad technology, voice-output device) for commu- nication and mistakenly assume that the effectiveness of the treatment is based on the provision of technology-based communicative techniques.

Such an approach would be problematic for several reasons. First, without considering the antecedents and reinforcement contingencies associated with challenging behavior, while focusing solely on training communica- tion using technology-based modalities, it is likely the treatment will fail to effectively treat the challenging behavior because the contingencies con- trolling the behavior will not have been addressed. Thus, to address the con- tingencies controlling the behavior, the effective applied behavior analyst considers the behavioral mechanisms responsible for the challenging behav- ior as well as the target-appropriate communicative behaviors (technology- based or otherwise). In addition, asBaer et al. (1968)asserted, without using a conceptual system when implementing the treatment, it is unlikely the cli- nician will generalize and apply the treatment effectively in other situations.

Guercio et al. (2012)provided an example of the application of a treat- ment based on a behavioral conceptual system for adult pathological gam- blers in individuals with acquired brain injury. As described previously, the authors implemented a program that consisted of one-on-one treatment therapy sessions in which they focused on teaching the participants about the MOs, antecedents, and reinforcers associated with gambling behaviors.

Thus, the treatment was explicitly based on behavioral mechanisms concep- tualized as controlling gambling behavior. An alternative conceptualization of the treatment might minimize or omit the behavioral components of the approach and instead focus on the format for therapy (e.g., one-on-one ses- sions, client-centered discussions). Similar to FCT, however, the focus and reliance on behavioral mechanisms is vital to the effectiveness of the treat- ment as well as the effective generalization and application of the procedures by future clinicians.

The use of a behavioral conceptual system is also emphasized in the area of OBM. For example,Cunningham and Austin (2007)utilized an interven- tion package consisting of goal setting, task clarification (via modeling), and feedback (description of performance, praise) via weekly meetings to improve the performance of hospital operating room employees pertaining to hands-free operating techniques. The authors conceptualized the behav- ioral mechanism of the feedback component of the intervention package as positive reinforcement of the target behavior. An alternative conceptualiza- tion that would not incorporate an underlying behavioral mechanism might focus not on the mechanism of reinforcement, but rather the implementa- tion of weekly meetings to discuss the performance of staff. However, future attempted applications of the intervention that emphasize elements of the intervention that were not responsible for the observed positive behavior (rather than the behavioral mechanism responsible; i.e., positive reinforce- ment) would be much less likely to be effective. It should also be noted that although not explicitly stated in the study, the goal setting and modeling components could be conceptualized as antecedent-based and intended to increase discrimination and occasion the desired behaviors.

Effective

Effectivenessis a dimension that emphasizes the practical quality of ABA prac- tices. That is, theeffectivenessdimension of ABA focuses on whether the indi- vidual whose behavior was changed and the family and care providers of the individual view the behavior change to be practical and significant. Applied behavior analysts determine theeffectivenessof their procedures by evaluating their data, often through visual inspection using valid single-subject exper- imental designs (as opposed to the use of statistical procedures to determine if behavior change is significant). Additionally, ABA emphasizes judgments of socially acceptable levels of improvement of target behaviors.

An example from the child-based ABA literature pertains to the assess- ment and treatment of pica. Pica (i.e., the insertion of inedible objects into

the oral cavity or the ingestion of inedible objects; Piazza et al., 1998;

Roane, Kelly, & Fisher, 2003) can be a life-threatening behavior displayed by children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Falcomata, Roane, and Pabico (2007)conducted a study that involved the assessment and treatment of pica in a 12-year-old boy with autism. During the study, the authors evaluated several treatment approaches by comparing their effects to each other as well as baseline conditions. The treatments included enriched environment (i.e., continuous access to highly preferred stimuli) and enriched environment plus a timeout procedure (i.e., visual screen time- out). The results showed that both treatments were effective at decreasing pica in comparison to baseline conditions. However, although the enriched environment treatment decreased pica relative to baseline (in which a mean rate of 6.7 occurrences per minute were observed), pica still occurred at a mean of 1.8 occurrences per minute. Thus, although it could be argued that the treatment produced an improvement, the dangerous nature of the behavior dictated that this was not a practical, oreffective, level of improve- ment. An acceptable level of practical improvement (i.e., a demonstration of effectiveness) with a dangerous behavior such as pica is zero or near zero occurrences. The results of the study also showed, however, that the second treatment consisting of enriched environment plus timeout produced near zero levels of pica. Thus, this was considered a practical outcome, and the treatment could be deemed effective.

A study conducted byNormand and Osborne (2010)provides an exam- ple of the demonstration of effectiveness within an adult-focused application of ABA to healthier food choices demonstrated by college students. The authors first implemented a baseline condition in which they assessed college students’ food choices via receipts and food checklists and tracked their daily calorie intake. Next, the authors implemented an intervention that involved providing feedback to the students by showing them graphs depicting daily calorie and fat intake. Additionally, the authors provided information to the students on recommended daily consumption for food groups as well as recommended levels of sugar and fat intake. Decreases in calorie and fat intake were demonstrated with three of the four participants. With each of the participants for whom clear effects of the intervention were demon- strated, their intake levels during the intervention condition occurred at or below United States Dairy Association (USDA) recommended daily guide- lines. The clear demonstration of an experimental effect within the multiple- baseline, single-subject experimental design in Normand and Osborne did not, in and of itself, confirm theeffectivenessof the intervention. However,

the USDA recommended daily guidelines provided a benchmark with which to evaluate effectiveness; the favorable comparison to that benchmark provided clear evidence of the effectiveness of the intervention.

Lebbon, Sigurdsson, and Austin (2012)provided an example of the dem- onstration of effectiveness in OBM-based ABA research. The authors eval- uated an intervention package consisting of training, peer observations, peer-directed feedback, and graphic feedback. To evaluate the intervention package, the authors collected data on several dependent variables including Occupational Safety Health Administration recordable incidents, lost work- days, and peer observations. The results suggested that the intervention package decreased the total number of incidents and lost days when com- pared to preintervention conditions. The authors provided a cost- effectiveness analysis by comparing the average direct cost of individual work-related disabling injuries and other injuries to the total cost of the intervention given the reduction in injuries during the course of the study.

The results suggested that the intervention was clearly cost-effective, pro- viding evidence of theeffectivenessof the intervention.

Generality

The last dimension of ABA places an emphasis on the extent to which gains aregeneralizableto other settings, caregivers, or behaviors.Generalizationis important because it is not beneficial to improve a client’s behavior only in settings (e.g., clinics) outside of the natural environment, particularly if the client only spends a few hours of his/her week outside the natural envi- ronment. The behavioral intervention is only beneficial if it improves behavior across different settings and when it is implemented by different individuals (e.g., multiple caregivers).

Silber and Martens (2010) provided an example of the application of child-focused ABA in which the dimension of generality was evident.

The authors evaluated a multiple exemplar approach to a program for gen- eralized oral reading fluency demonstrated by children in the first and second grades. Specifically, the authors compared three conditions including a con- trol, a reading intervention that consisted of teaching key words and sen- tence structures, and a typical reading intervention consisting of preview and repeated readings. Following the implementation of each condition, the authors conducted probes with nontrained reading passages to evaluate the extent to which the children’s learned skills generalized. The results showed that both reading interventions were more effective at promoting generalization of reading skills as evidenced by significantly higher scores

during the generalization probes with untrained readings. By showing the spread of the positive effects of the interventions to untrained reading pas- sages, the authors demonstrated the generality of the interventions.

Stokes, Luiselli, Reed, and Fleming (2010)provided an example of the emphasis on generalization in the ABA-based sports management literature.

During the study, the authors evaluated the utility of descriptive feedback alone; descriptive feedback in combination with video-based feedback;

and a combination of descriptive feedback, video-based feedback, and an audio-based feedback procedure (i.e., teaching with acoustical guidance, TAG) to improve line pass-blocking skills in high school football players.

After demonstrating the effectiveness of the intervention package consisting of descriptive feedback, video-based feedback, and TAG with improve- ments in blocking, the authors assessed improvements during game situa- tions (with four of the five participants) in the absence of the intervention. The results showed that all four players demonstrated high levels of correct blocking techniques during game situations suggesting that generalization had occurred with the intervention.

Thegeneralitydimension of ABA is also illustrated in numerous OBM- based ABA studies. For example, as described earlier, Ludwig and Geller (1997) evaluated two approaches to improving intersection stopping by pizza delivery drivers as well as generalization to nontargeted safe driving behaviors (i.e., turn signal usage, safety belt usage). Both interventions were shown to improve intersection stopping. However, significant increases in nontargeted turn signal and safety belt usage were demonstrated with the drivers who participated in the goal-setting process. Thus, the results sug- gested a high level of generalityof the intervention.

SUMMARY

Features of ABA include seven dimensions described by Baer et al. (1968) including applied, behavioral, analytic, technological, conceptually systematic, effective, and generalizable. Applied behavior analysts, through both applied work and research, have conducted practice characterized by these dimensions and features across populations and specific areas of focus for more than a half- century. In addition, assessment and intervention practices based on the prin- ciples of ABA have been implemented successfully in educational, clinical, sports, and business settings to address a wide range of behavioral issues.

This chapter highlighted the wide breadth and diversity of application of procedures and methodologies based on the discipline of ABA. Despite the

impression that ABA is synonymous with specific assessment and treatment approaches to autism and developmental disabilities (e.g.,Bowman & Baker, 2014), the wide range of studies described in this chapter in terms of popula- tions, areas of focus, and settings illustrates the actual nature of the impact and discipline of ABA.

REFERENCES

Athens, E. S., & Vollmer, T. R. (2010). An investigation of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without extinction.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,43, 569–589.

Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,1, 91–97.

Baker, J. C., LeBlanc, L. A., Raetz, P. B., & Hilton, L. C. (2011). Assessment and treatment of hoarding in an individual with dementia.Behavior Therapy,42, 135–142.

Borrero, C. S., Woods, J. N., Borrero, J. C., Masler, E. A., & Lesser, A. D. (2010). Descrip- tive analyses of pediatric food refusal and acceptance.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43, 71–88.

Bowman, R. A., & Baker, J. P. (2014). Screams, slaps, and love: The strange birth of applied behavior analysis.Pediatrics,133(3), 364–366.

Carr, E. G., & Durand, V. M. (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional com- munication training.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,18, 111–126.

Cunningham, T. R., & Austin, J. (2007). Using goal setting, task clarification, and feedback to increase the use of the hands-free technique by hospital operation room staff.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,40, 673–677.

Falcomata, T. S., Roane, H. S., & Pabico, R. R. (2007). Unintentional stimulus control dur- ing the treatment of pica displayed by a young man with autism.Research in Autism Spec- trum Disorders,1, 350–359.

Fienup, D. M., Luiselli, J. K., Joy, M., Smyth, D., & Stein, R. (2013). Functional assessment and intervention for organizational behavior change: Improving the timeliness of staff meetings at a human services organization.Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 33, 252–264.

Fisher, W., Piazza, C., Cataldo, M., Harrell, R., Jefferson, G., & Conner, R. (1993). Func- tional communication training with and without extinction and punishment.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,26, 23–36.

Fogel, V. A., Miltenberger, R. G., Graves, R., & Koehler, S. (2010). The effects of exergam- ing on physical activity among inactive children in a physical education classroom.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,43, 591–600.

Goomas, D. T., Smith, S. M., & Ludwig, T. D. (2011). Business activity monitoring: Real- time group goals and feedback using an overhead scoreboard in a distribution center.

Journal of Organizational Behavior Management,31, 196–209.

Guercio, J. M., Johnson, T., & Dixon, M. R. (2012). Behavioral treatment for pathological gambling in persons with acquired brain injury.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,45, 485–495.

Hagopian, L. P., Fisher, W. W., Sullivan, M. T., Acquisto, J., & LeBlanc, L. A. (1998). Effec- tiveness of functional communication training with and without extinction and punish- ment: A summary of 21 inpatient cases.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,31, 211–235.

Howard, J. S., Stanislaw, H., Green, G., Sparkman, C. R., & Cohen, H. G. (2014). Com- parison of behavior analytic and eclectic early interventions for young children with autism after three years.Research in Developmental Disabilities,35, 3326–3344.

Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1994).

Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 197–209 [Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982].

Kadey, H., Piazza, C. C., Rivas, K. M., & Zeleny, J. (2013). An evaluation of texture manip- ulations to increase swallowing.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,46, 539–543.

Kadey, H. J., Roane, H. S., Diaz, J. C., & Merrow, J. M. (2013). An evaluation of chewing and swallowing for a child diagnosed with autism.Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities,25, 343–354.

Lancioni, G. E., O’Reilly, M. F., Singh, N. N., Green, V. A., Oliva, D., Buonocunto, F., et al. (2012). Special text messaging communication systems for persons with multiple disabilities.Developmental Neurorehabilitation,15, 31–38.

LaRue, R. H., Stewart, V., Piazza, C. C., Volkert, V. M., Patel, M. R., & Zeleny, J. (2011).

Escape as reinforcement and escape extinction in the treatment of feeding problems.Jour- nal of Applied Behavior Analysis,44, 719–735.

Lebbon, A., Sigurdsson, S. O., & Austin, J. (2012). Behavioral safety in the food services industry: Challenges and outcomes.Journal of Organizational Behavior Management,32, 44–57.

Lerman, D. C., Tetreault, A., Hovanetz, A., Strobel, M., & Garro, J. (2008). Further eval- uation of a brief, intensive teacher-training model.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,41, 243–248.

Lerman, D. C., Vorndran, C. M., Addison, L., & Kuhn, S. C. (2004). Preparing teachers in evidence-based practices for young children with autism.School Psychology Review,33, 510–525.

Ludwig, T. D., & Geller, E. S. (1997). Assigned versus participative goal setting and response generalization: Managing injury control among professional pizza deliverers.Journal of Applied Psychology,82, 253–261.

Lustig, N. H., Ringdahl, J. E., Breznican, G., Romani, P., Scheib, M., & Vinquist, K. (2014).

Evaluation and treatment of socially inappropriate stereotypy.Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities,26, 225–235.

MacDonald, R., Parry-Cruwys, D., Dupere, S., & Ahearn, W. (2014). Assessing progress and outcome of early intensive behavioral intervention for toddlers with autism.Research in Developmental Disabilities,35, 3632–3644.

Martens, B. K., Werder, C. S., Hier, B. O., & Koenig, E. A. (2013). Fluency training in phoneme blending: A preliminary study of generalized effects.Journal of Behavioral Edu- cation,22, 16–36.

Matson, J. L., Tureck, K., Turygin, N., Beighley, J., & Rieske, R. (2012). Trends and topics in early intensive behavioral interventions for toddlers with autism.Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders,6, 1412–1417.

Nastally, B. L., Dixon, M. R., & Jackson, J. W. (2010). Manipulating slot machine preference in problem gamblers through contextual control.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,43, 125–129.

Normand, M. P. (2008). Increasing physical activity through self-monitoring, goal setting, and feedback.Behavioral Interventions,23, 227–236.

Normand, M. P., & Osborne, M. R. (2010). Promoting healthier food choices in college students using individualized dietary feedback.Behavioral Interventions,25, 183–190.

Northup, J., Fusilier, I., Swanson, V., Roane, H., & Borrero, J. (1997). An evaluation of methylphenidate as a potential establishing operation for some common classroom rein- forcers.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,30, 615–625.

Pampino, R. N., Jr., MacDonald, J. E., Mullin, J. E., & Wilder, D. A. (2004). Weekly feed- back vs. daily feedback: An application in retail. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management,23, 21–43.

Piazza, C. C., Fisher, W. W., Hanley, G. P., LeBlanc, L. A., Worsdell, A. S., Lindauer, S. E., et al. (1998). Treatment of pica through multiple analyses of its reinforcing functions.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,31, 165–189.

Ridgway, A., Northup, J., Pellegrin, A., LaRue, R., & Hightsoe, A. (2003). Effects of recess on the classroom behavior of children with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.School Psychology Quarterly,18, 253.

Roane, H. S., Kelly, M. L., & Fisher, W. W. (2003). The effects of noncontingent access to food on the rate of object mouthing across three settings.Journal of Applied Behavior Anal- ysis,36, 579–582.

Silber, J. M., & Martens, B. K. (2010). Programming for the generalization of oral reading fluency: Repeated readings of entire text versus multiple exemplars.Journal of Behavioral Education,19, 30–46.

Stokes, J. V., Luiselli, J. K., Reed, D. D., & Fleming, R. K. (2010). Behavioral coaching to improve offensive line pass-blocking skills of high school football athletes. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,43, 463–472.

Van Camp, C. M., & Hayes, L. B. (2012). Assessing and increasing physical activity.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,45, 871–875.

Vaz, P., Volkert, V. M., & Piazza, C. C. (2011). Using negative reinforcement to increase self-feeding in a child with food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 915–920.

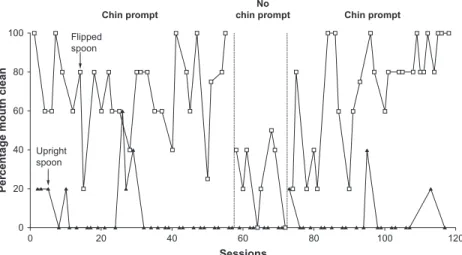

Volkert, V. M., Vaz, P., Piazza, C. C., Frese, J., & Barnett, L. (2011). Using a flipped spoon to decrease packing in children with feeding disorders.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 617–621.

Wacker, D. P., McMahon, C., Steege, M., Berg, W., Sasso, G., & Melloy, K. (1990). Appli- cations of a sequential alternating treatments design.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23, 333–339.http://dx.doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1990.23-333.

Applied Behavior Analytic Assessment and Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Wayne W. Fisher, Amanda N. Zangrillo

Center for Autism Spectrum Disorders, Munroe-Meyer Institute, The University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

Type the word “autism” into any Internet search engine and the abundance of returned results is overwhelming. The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has steadily increased, nearly tripling over the last decade (i.e., increasing from 1 in 150 children to approximately 1 in 50 children;Blumberg et al., 2013;

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2014). Given this increase, it is not surprising that caregivers, clinicians, and the general public are generating considerable discussion about ASD. Eugen Bleuler provided an initial descrip- tion of the symptoms of ASD in the early 1900s (Klinger, Dawson, & Renner, 2003). Over the past century, research has contributed significantly to the avail- ability of information regarding diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of ASD.

Unfortunately, not all research is created equal, and consumers are faced with the daunting task of differentiating empirical research and evidence-based prac- tice from that which is invalid or pseudoscientific (National Autism Center, 2009). In this chapter, we provide (a) a review of the diagnostic criteria and hall- marks of ASD and recent changes to the diagnostic criteria; (b) a discussion of the impact of the disorder in terms of prevalence rates, etiology, and prognosis; (c) an overview of behavior analytic, evidence-based approaches to assessment and treatment; and (d) future directions and considerations for practitioners.

A little learning is a dang’rous thing; Drink deep or taste not. . .

Alexander Pope

THE IMPACT OF ASD ON AFFECTED CHILDREN AND THEIR FAMILIES

The impact of autism on affected children and their families is difficult to overstate. In the absence of effective intervention, long-term outcomes for children diagnosed with ASD have generally been poor. For example,

Clinical and Organizational Applications of Applied Behavior Analysis ©2015 Elsevier Inc. 19 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-420249-8.00002-2 All rights reserved.