This dissertation presents a critical analysis of the participation of female academics in research in the humanities and social sciences in South Africa. This study arose from my participation in the audit of women academics by the former Center for Science Development (now part of the National Research Foundation).

Rank of Respondents by Institution Rank of Respondents (Black vs White) Rank of Respondents by Race and Region Years in Rank. Level of Institutional Support (KZN) Perceptions of sexism as an obstacle Perceptions of racism as an obstacle Research-related problems (National) Research-related problems (KZN) Mentors.

Chapter One

- Introduction

- Changing Times, Turning Tides?

- Comparing Notes with Jansen

- Conclusion

I acknowledge some of the studies done locally and abroad on the problems of women in academia. Chapter Two, Hunting Teddy Bears in the Parlor of the Academy? (a title adapted from Gulbrandsen, 1995) provides a critical synthesis of the literature addressing the problems of women in higher education.

Chapter Two

Introduction

She looks at the relevance and promotion of equity in science and mathematics education research, and reflects on various reports on higher education that highlight the racial and gender imbalance in the higher education sector. I also present a synopsis of some of the findings of a few studies on female academics in higher education.

Continuum of Outsiderness

Many of the trends reported by Aisenberg and Harrington (1988) were confirmed in the more recently published work of Nicolson (1996) who focused extensively, though not exclusively, on academic women. Dines concludes that 'One of the obstacles women face is the fact that they are not men' (1993,22).

Man-centred Universities - with some women in them!

The difference is in the rank of full professor, which is held by approximately 13 percent of women and 40 percent of men (Statistics Canada, 1991). The academic profession is aging and large numbers at the top of the 'teaching scale' (reached around the age of 40) are competing for promotion.

Networking, Mentors and Role models

Related to mentoring is the concept of "role models". Again, the terminology can refer to a range of functions and, as with mentoring, the meaning of an exemplary function is contested. For example, Brooks' (1997) questionnaire stated that: "role model - works when a person is used as a reference to imitate using a model to create a sense of self-identification." On this reading, role modeling was problematic for many of Brooks' respondents, as it is for me.

Teaching, Administrative and 'pastoral' commitments

Differences were also evident along disciplinary lines, with men and women in the humanities and social sciences more likely to report that teaching interferes with their research than those in the natural sciences.

Research Output

Networking and contact with colleagues can play an important role in research productivity.6 Female academics tend to have less effective access to networks than their male colleagues. Researchers who have been effectively mentored during their careers tend to be more productive than others; women academics have expressed a need in a number of studies.

The Question of Merit and Reward systems

Bagilhole suggests that, in the UK at least, women are "less successful" than men in getting research funding. The NBEET (1996) study shows that in Australia, even allowing for the lower proportion of female academics, women are under-represented in the range of applicants for ARC research grants.

Perceptions of Discrimination

Even more pertinent is the relationship drawn in the more analytical literature between masculinity, sites of power and influence, and the expression of an organizational culture that excludes and marginalizes women. While it is the case that in many cases academic women do express concern about patronage, prejudice, discrimination and discriminatory practices faced by women in academia, there appears to be a failure to operationalize this in any systematic way of sexism. of patriarchy in academia.

Domestic Responsibilities

Women may be reluctant to view their experiences as "discrimination" unless discrimination is overt; they may also interpret the problem as being related to their own performance or character (which of course they can do) rather than reflecting systemic factors.

Recurring Patterns

The small number of women in academia, the concentration of women in part-time, contract and fractional positions, together with the gender culture of universities lead to what has been aptly described as a "chilly climate" for women (see Payne and Shoemark, 1995). Although the experiences of women in academia are diverse, I have noticed that there are, however, recurring international patterns that suggest several areas in common.

The Silences

This pattern of disproportionate representation in undergraduate courses and at middle and lower levels of university employment ensures that it is male students and staff who set the research priorities and academic directions of the disciplines, and determine issues of policy, resourcing and general governance of the higher education system at national and institutional levels. levels.

What have men got to do with it?

Power Relations

To write about "female academics" is to affirm a contrast between men and women, but I am wary of speaking too strongly about "differences" between men and women. In recent years, much has been made of alleged differences in communication styles between men and women, both in the popular press and scholarly writing.I.

Conclusion

Such differences in communication style undoubtedly exist, but those who write about them may focus solely on gender, to the exclusion of other divisions in communication, such as culture, language, or even "disciplinary culture." Conversely, writers can focus on intercultural communication without considering gender.

Chapter Three

Introduction

Regardless of whether one moves from structures and hierarchies to the question of university culture, gendered patterns are always prevalent. I then focus on the role of the institution and the culture it embodies, concluding that the prevailing male-dominated culture must be seriously engaged, unpacked and reconstituted in a socially just form for women to begin to make inroads into knowledge production .

Centres of Meaning-making

- Male eyes, Male sensibilities!

- Taking things Personally

- The Race Question in Gender

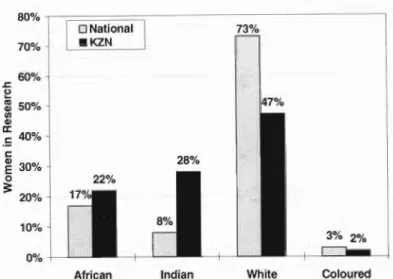

However, it is a focus on the power relations within the domains of patriarchal knowledge, phallocentric and sexist discourse that expands existing explanations of women's marginalization in academia. The statistical data is further enriched by the qualitative investigations of the problems of women in academia, through the eyes of black women academics in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Conclusion

The following chapters reveal the extent of the problem of women in research in South Africa by comparison with the province of KwaZulu-Natal. In continuation of this aim, I present data that opens a window into the seemingly harmless activities that take place in everyday life, and unpacks on these three aforementioned levels how female academics and researchers experience power relations, tensions and lived. the dialectic of the research world.

Chapter Four

Doing Research without Safety Nets!

Such research has traditionally taken place in contexts that encourage a general absence of critical reflection on how and why realities are studied as they are. Little of this explores the role of the researcher's life history in shaping research designs.

Background to the Study

- Establishing the Status of the status quo - the Women in Research Project

This has implications for vested interests and ownership of the research and reasons for participation. In the Faculty of Education, I used the women's research group to conduct focus group discussions as well as to develop those parts of the questionnaire that were our responsibility.

Conclusion

The development of such challenges requires that we begin to understand ourselves as part of the problem as well as part of the solution. The feminist gaze that framed the doctoral study forced the reconstitution of seemingly disparate threads such as the use of the survey method together with the conversations with women of color and the autobiography (Cortazzi, 1993).

Chapter Five

Introduction

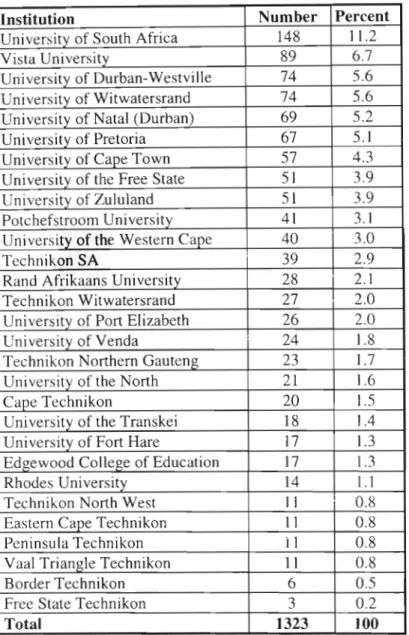

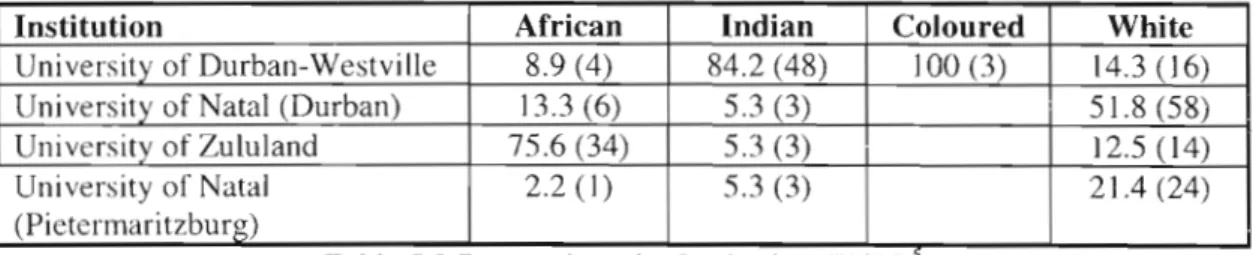

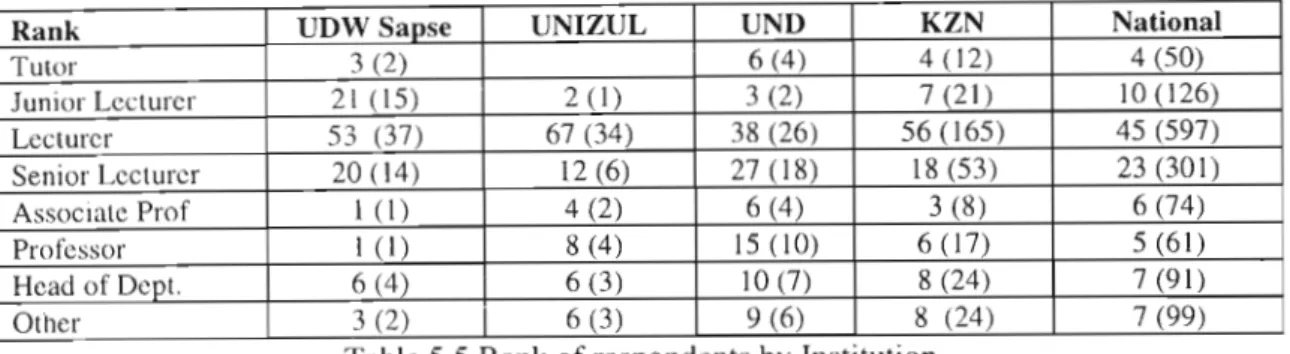

- Respondents by Institutions (KZN)

- Respondents by Discipline

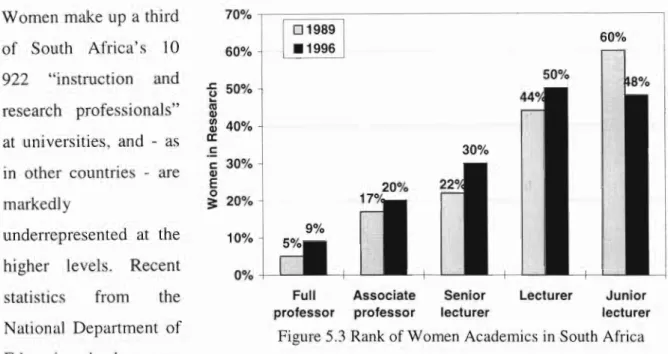

- Rank of Women Academics in South Africa

- Rank of Respondents (Black vs White)

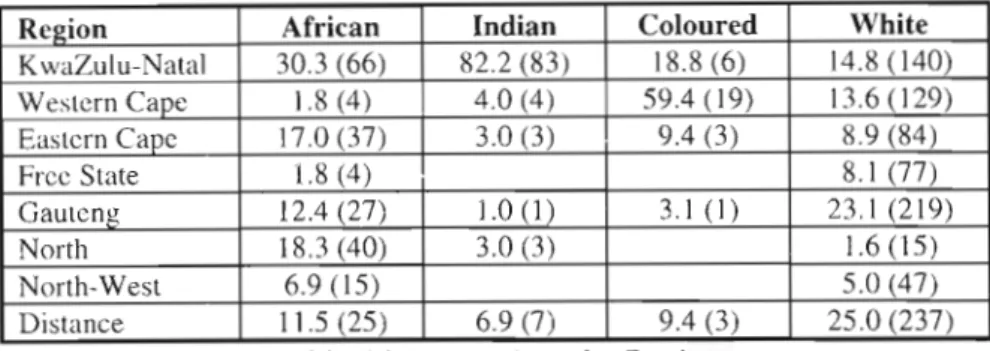

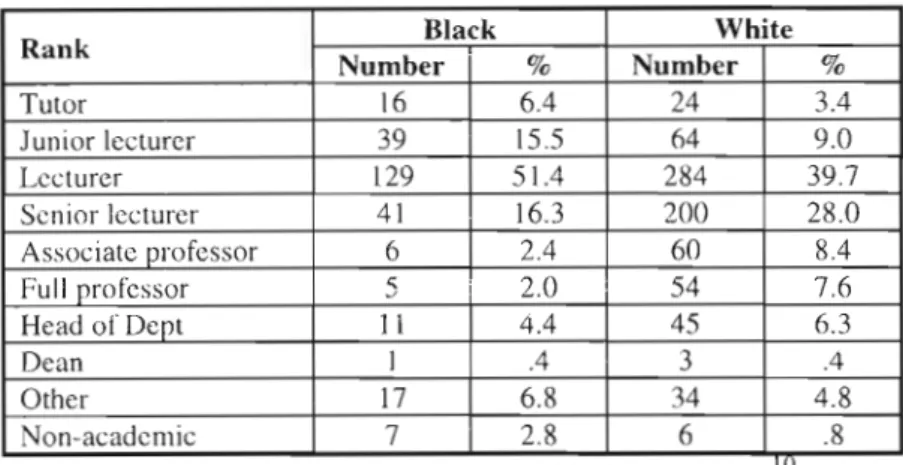

- Rank of Respondents by race and region

- When Qualification Obtained

- Marital Status

- Children (KZN)

- Number of Dependants

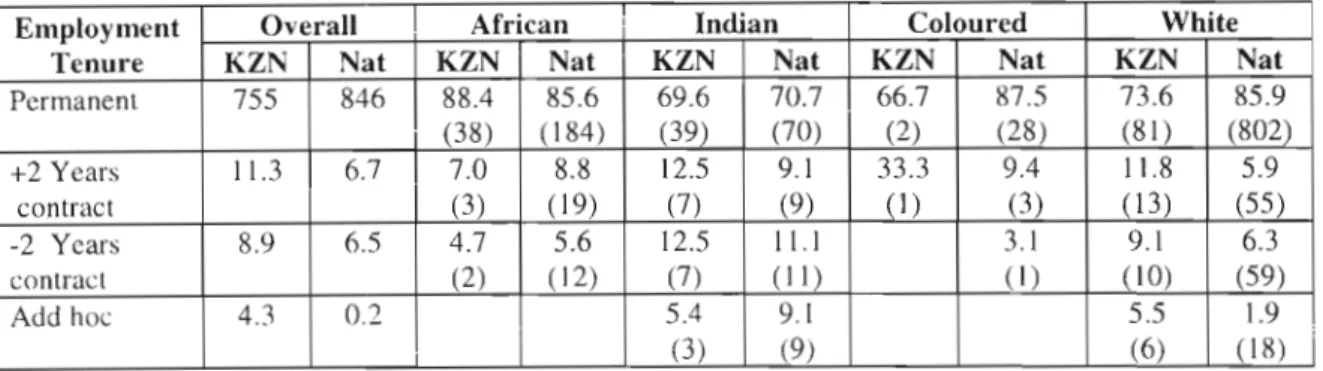

It is also important to note that only 0.3 percent of respondents were based in research units at their institutions. More than 55 percent of white respondents have held their current positions between 1 and 6 years.

Current Studies 1 Intent to Study

- Multiple Supervisors

- Perceptions of Discrimination

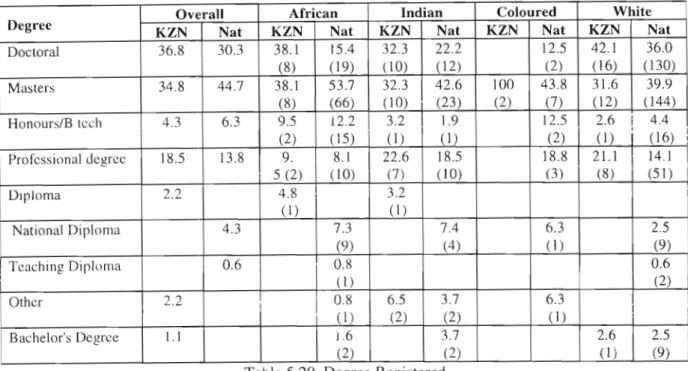

Overall, at least 90 percent of Women-in-Research respondents are studying part-time, as shown in Table 5.21. It is clear from Table 5.25 above that there is a higher percentage of respondents involved in NDP research within KZN than at national level.

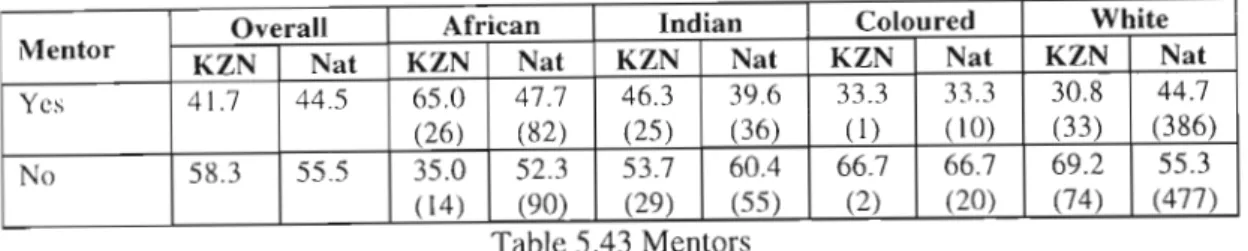

Mentors and Role Models

Furthermore, at least half of the Indian respondents both nationally and in KZN indicated that their mentor is also their supervisor. At least 50 percent of Indian respondents both nationally and in KZN have female role models.

Conclusion

This is why I take a qualitative turn in the next chapter to try to reach a deeper understanding of the problems women face as knowledge producers. I have previously argued that much of the research produced on women reflects the experiences of white women in the main.

Chapter Six

Introduction

This is followed by an analytical overview that theorizes some of the most important issues raised by the women's own reflections and analyses. I try to achieve this by first trying to construct the identities and partial realities of the women of this specific cultural group, individually, from their perspective.

I had to wait until I got smarter! Saras - an experienced academic (UDW)

We must continue the advocacy, achieve more and improve what we have. I must say that we need to combine the two research issues and the general problems of women academics.

I don't want to be an Oreo! Mandiswa - an experienced academic (UND)

It is very easy to identify the problems, but much more difficult to find solutions. Meanwhile, I feel it is more important to have women in the university.

Qualitative research actually liberates people! Phumzile - an experienced academic (UNIZUL)

In the US I had to take more research classes to be at the level they expect one to be for the PHD level. The way one worked, the way one analyzed the information and the books I read actually led me to believe that it is the research method, qualitative research that actually liberates people that you are researching.

Not white enough, not black enough! Shakti - a novice academic (UDW)

I also need to connect with others in my field in this region and they are mainly white women academics and researchers. No one seems to be protesting loudly enough to try to encourage and support black women researchers.

Feminism, a white man's trick to stir up trouble in the African society? Zinzi- a novice academic (UND)

In my culture, it is not acceptable to be an outspoken woman, a woman who has a mind of her own. But when I talk about how I think I want things to be, I am told that standards must be maintained, globalization, etc.

You won't get married if you do too much research! Thandeka -a novice academic (UNIZUL)

One of the conditions of the university is that you must start research at least most of the time. So if you can change people's perceptions, you don't have to go head-to-head.

Making research and academia a 'fairer' place

It is in the seemingly unintentional, patronizing attitude that white women brought with them to discussions and encounters that caused the deepest hurt and humiliation. White privilege was believed to have helped white women academics and researchers in finding employment and conducting research.

Conclusion

Chapter Seven

- Introduction

- Research as Me-Search

- The Dust Bowl Activists

- Hell is only a State of Mind!

- The Long Distance Mentor

- Subjective Scientist - an un(reason)able amalgamation?

My life as a student was never devoid of the political undertones that prevailed at the time. I believed wholeheartedly in the laws of science and its place at the top of the knowledge pyramid.