Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:57

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Viewpoint: Managing Change in Business Schools:

Focus on Faculty Responses

Michael G. Harvey , Milarod Novicevic , Kathryn J. Ready , Thomas Kuffel &

Alison Duke

To cite this article: Michael G. Harvey , Milarod Novicevic , Kathryn J. Ready , Thomas Kuffel & Alison Duke (2006) Viewpoint: Managing Change in Business Schools: Focus on Faculty Responses, Journal of Education for Business, 81:3, 160-164, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.3.160-164 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.3.160-164

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 26

View related articles

ABSTRACT.The authors’ purpose in

this article was to examine the

administra-tive challenges of change initiaadministra-tives in

busi-ness schools confronted by a changing and

more competitive environment. The authors

used traditional faculty role content as the

unit of analysis to address change

manage-ment issues from a school administrator’s

perspective. On the basis of the

administra-tor commitment to the mission-based status

quo versus the vision-based change, the

authors developed a framework to analyze

possible faculty responses to the

adminis-trative initiatives. The authors also outline

practical recommendations for the

advance-ment of administration in business schools.

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

Recent years have witnessed a variety of efforts to reengineer higher education into closer alignment with market prin-ciples and management approaches drawn from business…Such reengineer-ing efforts often entail an intermreengineer-inglreengineer-ing of three distinctively different organiza-tional paradigms within higher educa-tion: a professorial paradigm character-istic of traditional higher education organization, a bureaucratic machine paradigm representative of traditional business organization, and innovative or “adhocratic” paradigm defended by pro-ponents as a timely alternative to tradi-tional bureaucratic organization. This intermingling is often carried out in a fashion oblivious to the nuances of orga-nizational design and with little or no attention to the conflicts likely to result. (Green, 2003, pp. 196–197)

he increasing stakeholder pres-sure exerted on the institutions of higher education has elevated the rela-tive importance of teaching as a central school activity in the eyes of institu-tions’ constituents as well as the society as a whole (Atkinson, 2001; Burke & Modaressi, 2000; Moallem, 1997). Because they service the largest per-centage of university students, business schools are expected to develop compe-tence that yields learning outcomes that can be documented in terms of how and what they add to students’ cognitive, practical, and creative bases of knowl-edge during or after their educational experience (Ferris, 2002; Glaser, 1990; Novicevic & Buckley, 2001).

Many business schools have em-braced a number of innovative prac-tices, such as distance education, action learning (i.e., classes built around social problems where the stu-dents act as consultants), and team teaching, which are designed to enhance student learning experiences (McCowen, Ewell, & McConnell, 1995; Novicevic, Harvey, Buckley, & Keaton, 2003). This expansion of edu-cational innovations in modern busi-ness schools has in turn imposed new pressures on the traditional faculty role and has produced new challenges to business school administrators (Com-mission on the Academic Presidency, 1996).

Our purpose in this article was to examine the administrative challenges of change management in business schools, which are facing a changing and more competitive environment. We used the traditional faculty role content as the unit of analysis to address change management issues from a school administrator’s perspec-tive. On the basis of the administrator’s commitment to the mission-based tatus quo versus the vision-based change, we developed a framework to analyze possible faculty responses to the change management initiatives and offer practical recommendations for the advancement of administration in business schools.

Viewpoint

: Managing Change in Business

Schools: Focus on Faculty Responses

MICHAEL G. HARVEY KATHRYN J. READY THOMAS KUFFEL ALISON DUKE

MILAROD NOVICEVIC WINONA STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI WINONA, MINNESOTA WISCONSIN–LA CROSSE UNIVERSITY, MISSISSIPPI UNIVERSITY, MISSISSIPPI LA CROSSE, WISCONSIN

T

The Changing Role of Business Schools

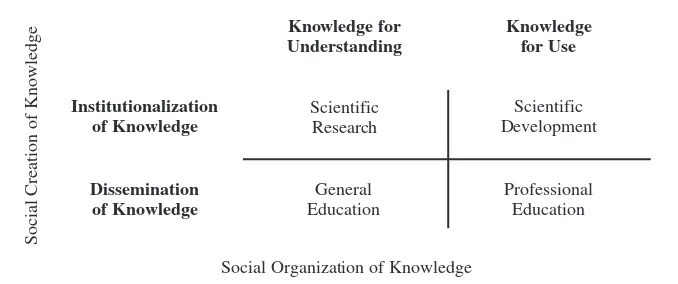

A business school is both the custodi-an custodi-and the communicator of knowledge about the business practices used in the society (Delbecco, 1999; Veysey, 1965). Beyond storing and communicating knowledge, the business school also fosters the research process that enhances general understanding and the cognitive capacity of society. The over-arching mission of the business school is to be responsible both for the contin-uous dissemination of new and evolving bodies of knowledge available to practi-tioners and for the institutionalized development of new faculty to continue the process discovering and developing knowledge (see Figure 1).

This multifaceted role of the business school as an institution engenders contra-dictory administrative demands for sta-bility and change. On the one hand, for smooth functioning of the business school as the repository and disseminator of knowledge, stability of the business school as an institution is encouraged— perhaps demanded—in the public domain. On the other hand, the business school is expected to be a creative and bold wellspring of new practices because the share of the population serviced by the business school has grown and the complexity of the required administra-tion has significantly increased (Masten, in press).

The juggling of stability and change in business schools is administratively chal-lenging in the public arena where new competitive pressures and budgetary con-straints are placed on the schools as insti-tutions. This juggling is further made more palpable as faculty positions con-tinue to go unfilled. For example, doc-toral faculty vacancy rates for positions authorized, funded, and unfilled were at 8.0% in 2001 (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business [AACSB], 2003), and the United States is expected to experience a shortage of 1,142 business faculty PhDs by 2007 and an estimated shortage of 2,419 in 2012 (AACSB, 2003). The resulting interplay among competitive, budgetary, and understaffing factors has only exacerbat-ed business schools’ neexacerbat-ed to use their fac-ulty resources more efficiently.

The Changing Role of Faculty in Business Schools

Institutions of higher education have historically provided their faculty with the privilege of a quiet life (Harvey, Buckley, Novicevic, & Elfessi, 2002). Vickers (1995) argued that “an impor-tant element of a faculty member’s quiet life is slack or X-inefficiency within an organization, inefficiency being cap-tured in low levels of effort by its facul-ty members to reduce costs, improve quality, and introduce innovative new ways of doing things, and correspond-ingly high levels of leisure” (p. 7). The labeling of faculty as the leisure class had been originally articulated in 1776 by Adam Smith (1981), a century before Verblen (1899) elaborated this concept. In particular, Adam Smith (1981) depicted the leisure of faculty in the 18th century at Oxford, where “the greater part of the public professors have, in these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching” (p. 761). In other words, like many tenured profes-sors today, faculty of those times had monopolistic discretion in how much of their leisure time would be allocated to their various academic priorities because their status was not affected by their choice (Ransom, 1993).

With the onset of the 21st century, the faculty role in business schools is chang-ing as the demand for knowledge devel-opment and use has rapidly increased and, moreover, as knowledge is created and disseminated by many sources other than business schools (i.e., corporate, pri-vate, and government research and

devel-opment centers). In addition, the tradi-tional modes of teaching are being chal-lenged by new methods enabled by tech-nological development and by changes in the student demographics (i.e., many of them employed, older, and with higher expectations), and the availability of resources (i.e., mostly money) for public business schools has been under serious taxpayer scrutiny and resistance to addi-tional funding (i.e., their refusals to com-mit to higher taxes makes future resource increases doubtful). In response, business schools have been pursuing change ini-tiatives to match the alignment with these external developments (Mintzberg & Gosling, 2002).

Over time, change initiatives may con-tribute to the institution’s operational effi-ciency, but only if accompanied by the support of insiders (i.e., faculty), whose “buy-in” may ensure that the changes are lasting (Bedeian, 2002; Twigg, 2000). Therefore, the crucial task of adminis-trators is how to manage the changing faculty role effectively in the new com-petitive and resource-constrained educa-tional environment to elicit faculty coop-eration in a goal-congruent manner (Novicevic et al., 2003).

Administrative Motives for the Redefinition of Faculty Roles

One of the main incentives for administrators to use faculty role redef-inition as a means to increase institu-tional effectiveness arises from the growing acceptance of educational per-formance comparisons based on the plethora of business school or college

FIGURE 1. The business school’s multiple roles in the 21st century: a matrix model.

Social Creation of Kno

wledge

Social Organization of Knowledge

rankings. The rank-driven competition motivates administrators of business schools to channel their change initia-tives toward the rating criteria that are valued by the school’s primary con-stituents (i.e., students, employers, and state officials). However, the rating-related measures of academic “quality” are seldom true indicators of the actual quality of education received by the average undergraduate student. In fact, because ratings of graduate education are crucial for the reputation and pres-tige of the institution, the students and their families do not know that the undergraduate learning environment is likely to be drained of limited resources to enhance the graduate rankings. In spite of their limited validity, rankings have the most powerful impact on the actual choices that business schools’ constituents make (e.g., in terms of funding, enrollment, and recruiting; Zimmerman, 2001).

As administrators face the increasing constituent pressures to improve the ranking of their individual institutions, cost-effectiveness of the faculty role is becoming one of the primary targets of their initiatives because colleges and business schools are human capital-intensive institutions where as much as 70% of the cost is related to personnel, and, if the faculty role is differentiated (i.e., if faculty functional tasks can be discretely represented), then faculty time and effort can be more efficiently managed. From an administrative per-spective, shifting the focus from an indi-vidual faculty role to the efficiency of the faculty as a whole is necessary to lower the costs of inevitable role-related dissatisfaction with increasing demands on the faculty. To implement such a shift, it is necessary for administrators to initiate the process of identifying or specifying the associated tasks or activ-ities within each functional component that are integral components of the fac-ulty role (Paulson, 2002).

A common rhetoric of administrators is that the specification of these tasks or activities is also required by accredita-tion agencies, whose imprimatur is eagerly sought in order to validate what the faculty is doing. Such validation in a professional program (e.g., business administration) is often seen (either

rightly or wrongly), as impressive to prospective employers and graduate schools. In the murky world of institu-tional politics and budgetary maneuver-ing, the validation provided by accredi-tation is also thought to yield a positive “edge” to the accredited program. Therefore, the transparency of a faculty role is a part of both the internal and external business school agendas (de Russy, 1996; Gallos, 2002; Leslie, 1996).

In general, a faculty role incorporates three main functional components: (a) teaching, (b) research, and (c) ser-vice. For efficient management of these components, educational administrators should consider the risks and benefits of either outsourcing or internally con-tracting any and each of these functions to clinical or part-time teachers, researchers, professional advisors, and administrators. The analysis of these two structural alternatives requires dis-crete representation (i.e., identification and specification) of function-specific tasks and activities. The tasks compris-ing the teachcompris-ing-related activities of the faculty members’ job are: (a) designing course and curriculum; (b) developing course, curriculum, methods, and mate-rials; (c) mediating the learning process; (d) delivering the subject matter; (e) assessing student learning though meth-ods, assignments, or grading; and (f) advising students academically. Man-agement of these tasks or activities should be primarily analyzed from an efficiency perspective (Levin, 1991).

The technology-enabled, resource-intensive, and competency-driven new rivals of traditional institutions are increasingly contracting discrete tasks of instructional activities. Design is contracted in to committees or out to national authorities; development is contracted out to providers of educa-tional solutions; mediation is contracted in and out to instructional or teaching professionals; delivery is contracted in and out to institutional or teaching pro-fessionals, Webmasters, and instruction-al technologists; and assessment is con-tracted in or out to competency testing or assessment centers. Also, the rivals are subcontracting research to special-ized institutions and advising to advis-ing specialists. It appears that virtually

no core activities, other than contract coordination, require the crucial agency of a full-time professor in these “mean-and-lean,” and often virtual, entrants to the educational arena (Paulson, 2002; Wang, 1981).

Administrators in traditional institu-tions face difficulties when trying to replicate efficient solutions of new rivals because business schools are gov-erned like governments (i.e., faculty exercise democratic control over a range of significant decisions), whereas they compete like firms (i.e., offering service for a price and competing against each other both in input and output markets; Masten, 2000). In other words, adminis-trative discretion in decision making is constrained by faculty participation in business school governance, which safeguards academic freedom while making the decision-making processes slow to change, cumbersome to imple-ment, and protective of entrenched interests. Because of this inert nature of governance, any change initiative planned by administrators should be assessed in terms of the desired extent of change (i.e., commitment to the vision versus commitment to the mis-sion of the institution). This assessment should be particularly focused on possi-ble responses by the faculty body as a whole (Bartem & Manning, 2001).

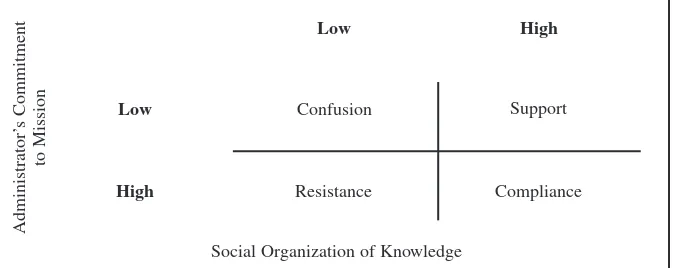

Faculty Responses to Change Initiatives

The challenge of business school administrators is how to craft, through consultations, a statement of purpose and direction of change that is inspiring to both the internal and external con-stituents of the institution. The crafting of the statement requires administrators to seek a balance between anchoring the change initiative either in the stable mission of the school or in the dynamic vision of its change. The dilemma of the appropriate trade-off in administrator’s commitment choice should be addres-sed in terms of possible responses to the change initiative by the faculty as a whole (see Figure 2).

The faculty response that is ideal for the administrator would be a support for the vision of change, which is uncon-strained by the inertia or strings of the

institution’s mission (see Figure 2). For support to occur, the administrator needs to exhibit transformational leadership in influencing change in faculty preferences for acceptance of the change initiative in terms of the proposed innovations, cost reductions, and the associated degree of faculty role unbundling.

When the strings of the mission are pulled along with the vision (as shown in the lower right corner of Figure 2), the administrator has to be charismatic in influencing faculty to sacrifice their self-interest while complying with the change initiative that is to align the mis-sion with the vimis-sion. The drawback of this response is that the faculty is less likely to exhibit organizational citizen-ship behavior.

When the administrator is neither firmly committed to the vision of change nor to the stable reliance on the institution’s mission, the administrator will commonly try to imitate the “best practice” initiative pursued by some flagship business school. The likely fac-ulty response, confusion (see Figure 2), as the anarchic implementation of change initiative, will evolve in a sus-pended animation because of the lack of anchoring in the institution’s direction and purpose.

When the administrator is primarily committed to the institution’s mission, a bias toward status quo will occur, as the change initiative will be likely pur-sued involuntarily under external pres-sure. The faculty will exhibit resis-tance (see Figure 2) because they will have no understanding of how the change initiative contributes to the institution’s goals.

CONCLUSION

The static, hierarchical, tradition-bound business schools have been reluctant to improve their operating pro-ductivity, to adapt to the needs of their students, or to predict what employers expect their students to know. Most of all, business schools have not found a formal way to motivate faculty mem-bers to accept initiatives for change (Massy & Zemsky, 1994). Because the focal point of any needs analysis or change initiative is faculty role redefini-tion, the administrators must seek an appropriate way to recognize faculty responses to change initiatives.

The need to overcome faculty resis-tance to change is becoming critical for administrators because the inertia of historic institutional governance and inefficiency facing the rapid globaliza-tion, deregulaglobaliza-tion, and technological advances in education are of growing concern to the business school’s criti-cal constituents (i.e., legislators, ad-ministrators, students and their fami-lies, and recruiters). The concern grows as a new set of technology-enabled institutions, coming from var-ious geographies, has entered the edu-cational market to challenge the seemingly monopolistic position of business schools. Unfortunately, a typ-ical response of many administrators in institutions of higher learning has been hesitation until the new practices become widespread. The basic premise of our article is that the strategy of hes-itation should be terminated by the use of the anticipatory frameworks we have proposed herein.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Kathryn J. Ready, PhD, Professor of Management, College of Business, Somsen 302, Winona State University, Winona, MN 55987. E-mail: kready@winona.edu

REFERENCES

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2003). Sustaining scholar-ship in business schools. AACSB eNewsline, 7(3): 1–2. Retrieved August 15, 2005, from www.aacsb.edu/publications/dfc/default.asp Atkinson, M. (2001). The scholarship of teaching

and learning: Reconceptualizing scholarship and transforming the academy. Social Forces, 79(4), 1217–1230.

Bartem, R., & Manning, S. (2001). Outsourcing in higher education. Change, 33(1), 43–47. Bedeian, A. (2002). The dean’s disease: How the

darker side of power manifests itself in the office of dean. Academy of Management Learn-ing & Education,1(2), 164–173.

Burke, J., & Modarresi, S. (2000). To keep or not to keep performance funding: Signals from stakeholders. Journal of Higher Education,

71(4), 454–473.

Commission on the Academic Presidency. (1996).

Renewing the academic presidency: Stronger leadership for tougher times. Washington, DC: Association of Governing Boards of Business Schools and Colleges.

Delbecco, A. (1999). Review of rethinking man-agement education. Administrative Science Quarterly,44,439–443.

de Russy, C. (1996, October 11). Public business schools need rigorous oversight by activist trustees. Chronicle of Higher Education, B3–B4. Ferris, W. (2002). Students as junior partners, pro-fessors as senior partners, the B-school as the firm: A new model for collegiate business edu-cation. Academy of Management Learning & Education,1(2), 185–193.

Gallos, J. (2002). The dean’s squeeze: The myths and realities of academic leadership in the mid-dle. Academy of Management Learning & Edu-cation,1(2), 174–184.

Glaser, R. (1990). The reemergence of learning theory within instructional research. American Psychologist, 45, 29–39.

Green, R. (2003, January). Market, management, and “reengineering” higher education. The Annals of American Association of Political and Social Sciences,585, 196–213.

Harvey, M., Buckley, M., Novicevic, M., & Elfes-si, A. (2002). Developing a timescape-based framework for an online education strategy.

International Journal of Educational Manage-ment,16(1), 46–54.

Leslie, D. (1996). Strategic governance: The wrong questions? The Review of Higher Educa-tion, 20(1), 101–112.

Levin, H. (1991). Raising productivity in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 62, 241–262.

Massy, W., & Zemsky. R. (1994). Faculty discre-tionary time: Departments and academic ratch-et.Journal of Higher Education, 65(1), 1–22. Masten, S. (in press). Authority and commitment:

Why universities, like legislatures, are not orga-nized as firms. Journal of Economic and Man-agement Strategy.

McCowen, M., Ewell, B., & McConnell, P. (1995). Creative conversations: An experiment in interdisciplinary team teaching. College

FIGURE 2. Faculty responses to change initiative.

Low

Social Organization of Knowledge

Teaching, 43, 127–131.

Mintzberg, H., & Gosling, J. (2002). Educating managers beyond borders. Academy of Man-agement Learning and Education,9(1), 64–76. Moallem, M. (1997). Review of instructional plan-ning: A guide for teachers. Educational Technol-ogy Research and Development, 45(4), 88–95. Novicevic, M., & Buckley, M. (2001). How to

prepare the next generation graduates for the contemporary knowledge-intensive workplace.

Performance Improvement Quarterly, 14(2), 125–144.

Novicevic, M., Harvey, M., Buckley, M., & Keaton, P. (2003). Latent impediments to qual-ity: Collaborative teaching and faculty goal

conflict. Quality Assurance in Education. 150–156.

Paulson, K. (2002). Reconfiguring faculty roles for virtual settings. The Journal of Higher Edu-cation, 73(1), 127–139.

Ransom, M. (1993). Seniority and monopsony in the academic labor market.American Econom-ic Review, 83(1) , 221–233.

Smith, A. (1981). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations.R. Campbell, A. Skinner, & W. Todd (Eds.). Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund. (Original work published 1776). Twigg, C. (2000). Who owns online courses and course materials? Intellectual property policies for a new learning environment. Retrieved May

17, 2004, from http://center.rpi.edu/PewSym/ Mono2.pdf

Verblen, T. (1899). The theory of the leisure class. New York: MacMillan.

Veysey, L. (1965). The emergence of the American business school.Chicago: The Business School of Chicago Press.

Vickers, J. (1995). Concepts of competition.

Oxford Economic Papers,47, 1–23.

Wang, W. (1981). The dismantling of higher edu-cation.Improving College and Business School Teaching,29(2), 55–60.

Zimmerman, J. (2001). Can American business schools survive?Unpublished manuscript, Uni-versity of Rochester, New York.