SPECIAL ISSUE

SOCIAL PROCESSES OF ENVIRONMENTAL VALUATION

The

VALSE

project — an introduction

Martin O’Connor

C3ED Uni6ersite´ de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Y6elines, 47boule6ard Vauban,78047Guyancourt,cedex,France

www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

1. The VALSE project

This Special Issue of Ecological Economics pre-sents results from The VALSE Project (VALua-tion for Sustainable Environments), a co-operative international programme of research undertaken during 1996 – 1998 with the financial support of the European Commission. The re-search team set out with the goal to demonstrate effective social processes for valuation of environ-mental amenities and natural capital for conserva-tion and sustainability policy purposes.

The project was financed under the European Commission’s Environment and Climate Re-search Programme (1994 – 1998): ReRe-search Area 4 Human Dimension of Environmental Change (Contract no. ENV4 – CT96 – 0226). The full de-scriptive title was: ‘Social Processes for Environ-mental Valuation: Procedures and Institutions for Social Valuations of Natural Capitals in Environ-mental Conservation and Sustainability Policy’. In the project, valuation and choice have been approached ‘from the point of view of complex-ity’. By this term, we mean that the question of

the value or significance of environmental assets, services and features is considered in a multi-di-mensional perspective, reflecting the variety of scales over which a problem may be considered and the range of individual and collective interests and preoccupations that may be involved.

Individuals have specific interests in the envi-ronment as habitat, recreational space, cher-ished heritage, and space of economic opportunities;

There are social and collective dimensions of choice reflecting both scientific and social prop-erties of the choice situations;

Scientific features of significance may include the indivisibility — that is, the collective char-acter — of many environmental goods, services and hazards, the irreversibilities of environmen-tal change, and the uncertainties of complex systems;

People can express views, individually and as participants in community, on dimensions of value relating to collective identity;

Issues of fairness, justice and responsibility in-clude considerations relating to the geographi-cal and inter-temporal distributions of costs, risks and benefits, and extend to conflicts and compromises over what is just, right, and proper.

E-mail address: [email protected] (M. O’Con-nor).

In our view, valuation is not primarily a technical matter of quantifying substitution ratios (which, depending on circumstance, might be supply-side opportunity costs or demand-side subjective trade-off preferences). Rather, we consider that value statements about the environment typically emerge out of social processes of controversy and conflict. All choices, individual and collective, can be seen as value statements (implicit and explicit), but there is not a simple aggregation of prefer-ences. Different social processes for environmen-tal valuation and management will tend to elicit different evaluative responses. Valuation practices have a greater chance of social legitimacy and policy usefulness when they are implemented with awareness of the deep social and institutional dimensions of value formation.

The VALSE project set out to demonstrate

these contentions through the design and imple-mentation of effective procedures for eliciting en-vironmental valuation statements and for addressing the conflicts that arise in four real situations of natural resource and environmental decision-making. The work programme had four main aspects:

Phase I was the translation of general princi-ples for effective environmental valuation pro-cedures that had been established from previous empirical and theoretical research and discus-sion, into a range of working hypotheses about key physical, institutional, and ethical factors in the social construction of environmental values.

Phase II made the passage from these method-ological considerations to detailed research de-sign and valuation practices appropriate for the specific features of four case studies — carried out in Spain, Italy, France and the United Kingdom.

Phase III saw the reverse movement, from the case studies back to wider methodological reflection, so as to formulate recommendations about valuation practices as components in en-vironmental policy design and public expendi-ture evaluation programmes.

Phase IV is the communication of the project results to policymakers, researchers, and the interested public. This is accomplished formally through workshops and symposia and a set of

supporting written documents — including this paper — and also informally through the ways that knowledge of the VALSE research is ab-sorbed into these communities.

2. The case studies

Each of the VALSE case studies addressed situations of natural resource and systems man-agement, notably water resources, forest and agri-cultural lands.

UK: economic and environmental values of proposed reconversion of agricultural land into wetland fen.

France: social, ecological and economic valua-tion of forest pockets within farmland;

Spain: institutional and ecological factors de-termining changes in water quality and quantity management in the Canary Islands;

Italy: multiple criteria decision support analysis for identifying water resource use options for regional development in Troina, Sicily.

The research process, in each case, aimed simulta-neously at (1) assessing (in monetary and non-monetary terms) the importance of the environmental ‘values’ in question — that is, the nature of their actual or potential commitments for maintaining these values; and (2) integrating these valuation statements within a real decision-making process. This is what we mean by estab-lishing social processes for environmental valuation.

UK wet fens: contingent valuation (willingness

to pay) survey, citizens’ jury;

Canary Islands water: diagnostic systems

anal-ysis, institutional analysis;

France rural woodland: diagnostic systems

analysis, discourse analysis, in-depth inter-views, willingness-to-accept survey;

Sicily water and development: institutional

analysis, multi-criteria analysis, in-depth inter-views, attitudes and perceptions survey. We now introduce the case study findings in a synthetic way.

2.1. The UK agriculture 6ersus Wet Fens 6aluation

The valuation problem being considered was the justification (or not) for the re-construction of a now-rare ecosystem, that of wet fens. If ap-proached in the perspective of a conventional environmental cost benefit analysis, the aim will be to identify ‘highest value’ (viz., Pareto-optimal) levels of agricultural production, wetlands and any other resource use. This would mean compar-ing the costs of obtaincompar-ing further wet fens, for example, the loss of agricultural production, with the benefits of the enhanced environmental amenity obtained. Monetary valuation is sought so that the loss in relation to one objective can be quantified against the gain in relation to another. The framing hypothesis of the UK study was that different value-articulating processes tend to elicit different values. These differences are not just quantitative (for example, higher or lower money estimates), but also qualitative. In order to probe the character of contingent valuation and citizen’s jury methods, respectively, as inputs to policy and decision-making, the research team implemented two parallel processes, a contingent valuation survey (CVM) and a citizen’s jury (CJ) in which the merits of a ‘live’ project — a really existing proposal to restore wet fen habitat in East Anglia — were evaluated.

The wet fens CVM study was designed so as to obtain quantitative information and also to high-light questions of motivations lying behind peo-ple’s responses to questions about willingness-to-pay (Spash et al., 1998). The

essen-tial idea is that a CVM survey investigates ‘stated behaviour’, but behind these statements there are a range of perceptions, social norms, beliefs and habits which will determine what is stated and what degree of acceptance a person will have of differing policy options.

For the survey, the format of a trust fund was chosen to reflect the likely type of institutional arrangement that would arise from the really ex-isting lobby group, Wet Fens for the Future. This group is looking to create projects to achieve wetland restoration in The Fens, and is concerned to attract government and EC funding as well as private donations. The project being considered is an environmental improvement, and a willingness to pay question format was employed because any move towards an increase in wetlands in The Fens would require the purchase of farmland. The cen-tral question was left open-ended:

How much would you be willing to pay as a one-off contribution to the trust fund to help create wetland?

The amount an individual is willing to pay to create an area of wetland will vary with socio-eco-nomic characteristics. The study hypothesised that environmental attitudes and beliefs may also help explain the environmental values being expressed via contingent valuation surveys. Of the 713 indi-viduals interviewed, 36 (about 5%) refused to answer the willingness to pay question and 182 (about 26%) were unable to answer, responding ‘‘don’t know’’. Spash (2000) gives a detailed ex-amination of the attitudes and personal motiva-tions that, on the basis of statistical analysis of the survey responses, may plausibly lie behind the protest votes, the ‘‘zeroes’’ and the propositions of ‘‘don’t know’’.

Univer-sity), and local residents. The organisations repre-sented on the Advisory Group, along with some others, all have an interest in proposals made in recent years to create more wetland areas in the Fens. Some of them have been involved in the umbrella ‘Wet Fens for the Future’ project; others would be affected by the proposals being made. The Jury was asked to discuss the following question:

What priority, if any, should be given to the creation of wetlands in the Fens?

Sixteen jurors representing a cross-section of the population in the Fens and adjacent areas were recruited by a market research company, using house-to-house visits. The jurors were lay people with no particular prior expertise. They sat for four days, hearing evidence from a variety of expert and other witnesses, and discussing the issues surrounding wetland creation in small groups and in plenary session. The discussion was structured around options setting out different ways of creating wetland for different purposes (see Aldred and Jacobs, 1997, 2000). These op-tions were:

Establish a nature reserve (as put forward by the Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and North-amptonshire Wildlife Trust)

Incremental development of wetlands (throughout the Fens through small-scale, farmer-led schemes)

Multi-use recreational Fen centre (as set out by Norfolk College of Arts and Technology and others)

No deliberate action

Interestingly, after consideration of these four op-tions, the Jury constructed for themselves a fifth option — to establish a Fens ‘Covent Garden’ — centred on a local wholesale centre to distribute fruit and vegetables produced in the Fens. Their justification was that, in this way more of the added value in sales and distribution of Fens production could be retained in the Fens area. Local produce should be branded and marketed as such (for example as ‘Fen Food’). The job creation and economic development potential of such a centre may be significant.

The Citizens’ Jury proved to be highly effective for investigating value issues that divided and united different interest groups in the Fens com-munities. The options ‘No deliberate action’ and ‘Multi-use Fen centre’ were rejected. For the other three options — all considered to be realis-tic and desirable (the Nature Reserve, Incremental Development and Fens Covent Garden) — de-tailed recommendations on co-ordination and financial incentives were made. Not only were the Jury participants themselves convinced of the value of their debates and recommendations, but also local politicians became convinced of the value of the exercise.

2.2. The Canary Islands institutional analysis

Access to water resources in the Canary Islands has been a matter of conflict for centuries. In the context of the VALSE project, an institutional analysis was carried out in order to account for recent changes in the notion of water (conflict between commodity and public good perspectives) and corresponding changes in the institutional framework (see Aguilera Klink et al., 1997, 1998, 2000a,b). Inspired broadly by Norgaard’s perspec-tive on coevolutionary change, several distinct dimensions of the social process were identified and studied: water as a commodity; water in terms of environmental functions; social values; stakeholders’ interests; technology and science (linking to uncertainty and ignorance); and the institutional framework of water distribution and use.

small water owners, and curtailed public debate. The new law was abolished and a new government was elected by promising a new law that ‘will respect the rights’ for the next 75 years.

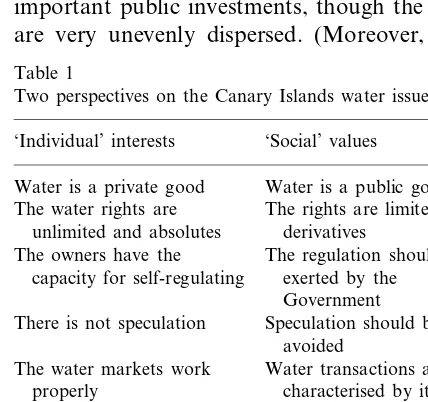

In the wake of this, the valuation problem can be presented as a contest between two perspectives on the water issues, as in Table 1 below. At present, the Individual Interests perspective prevails. While formally the water is defined as a public good, in reality it is largely exploited as a private commod-ity. The aquifer is on a path of irreversible deteri-oration due to overexploitation and resulting marine intrusion. In the short run the existing institutional arrangement respects the dominant water owners’ economic interests. But because of the worsening degradation, many water ‘owners’ are losing their not-very-well defined access rights. This aggravation of water scarcity results in pres-sure for new solutions. In the meapres-sures so far adopted, water management is posed as a technical question, such supply-side measures as construc-tion of new water distribuconstruc-tion networks (pipelines and pumps, small dams, etc.), residual water treat-ment and re-use in agriculture, impletreat-mentation of improved processes of brackish water and sea-wa-ter desalination. These supply measures involve important public investments, though the benefits are very unevenly dispersed. (Moreover, aquifer

deterioration is hastened by the brackish water desalination plants because they promote increased extraction).

Reform options can be appraised against three key norms — economic efficiency, sustainable use and democratic process. In brief:

2.2.1. Allocati6e efficiency of resource use

Pareto-efficiency in water resource use implies that water be allocated to its ‘highest value uses’ as defined by marginal costs and benefits. Because water resources allocation is determined by a com-plicated power-brokering system, some users have access at monetary costs per unit far lower than others. This is prima facie inefficient. It is also inequitable. A search for improved efficiency must confront obstacles related to property rights. First, vested interests having de facto ‘rights’ under the status quo will oppose changes reducing their opportunities. Second, efficient resource use is, in part, a function of the property rights that apply.

2.2.2. Sustainable water resource use

The Canaries aquifer water is a naturally renew-able resource vulnerrenew-able to degradation. The drop in water table and marine intrusion are irreversible in that it may take longer to obtain ‘recovery’ than it takes to degrade. Restrictions to water use so as to assure ‘sustainable use’ are proposed by some sectors of the Canaries society, and are also re-quired (legally) under norms set by the EC. Imple-mentation of such norms would confront the (re)distributional problems of, first, achieving re-duction to total water use relative to the status quo and, second, deciding which social and economic interests shall be provided for within constraints for sustainable use.

2.2.3. Democracy

The present situation is one where a democratic process has been usurped by powerful economic interests. Reclaiming democratic values thus en-tails a contesting of the status quo. Democracy as the social and daily process of practicing and defending values such as freedom, justice, equity and rights of coexistence not dictated by willing-ness-to-pay under status quo income distribution, involves a normative commitment. In this

per-Table 1

Two perspectives on the Canary Islands water issue ‘Social’ values ‘Individual’ interests

Water is a private good Water is a public good The water rights are The rights are limited and

derivatives unlimited and absolutes

The owners have the The regulation should be capacity for self-regulating exerted by the

Government There is not speculation Speculation should be

avoided

The water markets work Water transactions are characterised by its properly

opacity

Existence of fraud in the Existence of transparency in

water distribution the water distribution

The aquifer overexploitation Overexploitation is evident has not been demonstrated in some islands and

aquifers from a scientific point of

spective the water valuation problem in the Ca-nary Islands is largely a problem of political values and rights.

All three could be pursued simultaneously as a ‘first best’ policy in a multi-criteria management of water use. But the present situation is very far away from this possible first-best. The analysis highlights key scientific, economic and political process issues that must be faced for durable solutions to be found. A more democratic social valuation process would probably be accompa-nied by a stronger visibility of ‘sustainability’ and ‘social equity’ values in the debates.

2.3. Woodland in rural France: from transaction price to transmitted social6alue

The Bois de Bouchereau is a small forest islet of about 50 Ha situated in an agricultural region, an open field country called the ‘Gaˆtinais Nord-Occi-dental’, about 100 km to the south-west of Paris. This forest is composed of ‘parcels’ held as private property. The woodland has been, through differ-ent generations, progressively divided into (about) 284 woodlots, or parcels, actually owned by (about) 155 persons. It is an example of French ‘Ordinary Nature’, a natural space modified by human intervention over many centuries. No ma-jor conflict about the uses of the wood has ap-peared until now; the different uses as wood cutting, walking, hunting, daffodils gathering, and so on, coexist. The valuation question is one of understanding whether enough social significance is attached to the forest to ensure that it will sustained, and in what form.

In the first phase of the study, analyses were conducted that brought out the qualities of the forest socio-eco-system as an indivisible ‘unite´ de valeur’. Based on both institutional and ecosys-tems analysis, a dynamic simulation model was developed that represents the evolving forest sys-tem through the interaction of human and ecolog-ical forces (Heron 1997; O’Connor and Heron, 1999). The model expresses, as a sort of metaphor, the way that the forest is a sort of ‘social infrastructure’, described in terms of the variety of stakeholders (woodlot owners, adjacent farmers, hunters, visitors, and communal

adminis-trators) who contribute, and the variety of values attributed to the forest system.

The woodlots are transacted individually — mostly in the context of a hereditary transmission. The changes of ownership involve monetary transactions, administered through notary offices in the district. So there is a ‘price’ for a woodlot when it changes hands. But this is not really a ‘market for woodlots’. The variety of users and uses point to a high local significance of the woodland, associated mostly with the rural (vil-lage and agricultural) community life in the region (Noe¨l and Tsang King Sang, 1997). This high valuation is now ‘at risk’ due to demographic and lifestyle change tendencies. The locally resident population is growing older, and the process of rural depopulation means a growing proportion of distant owners.

A survey was devised for an enquiry into actual and hypothetical market-like transactions (defined by a quantity and a price), and also an enquiry into the motivations for the actions — that is, the social norms, customs, and individual beliefs — of the persons involved. The survey format com-bined specific data and quantitative information together with open-ended questions that would permit an ‘in-depth interview’. Deliberately, the questionnaire was simple, and focussed on the price and other conditions under which existing proprietors might be willing-to-accept sale of their parcel (see Noe¨l et al., 2000; and for the original survey in French see Boisvert et al., 1998).

2.4. The Troina (Sicily) water6aluation study

The water valuation problem for the Commune of Troina in Sicily began with the notion of a local water shortage in Troina, which could per-haps be remedied by more effective use of existing resources or by changing use priorities. It turned out that, although real water shortage is common in Sicily, Troina is an exception. The more signifi-cant factor was a complex and heterogeneous collection of interests in the Troina water issue, who up until now have had no effective dialogue. The primary research task was to achieve an effective structuring of the water problem so that negotiations among stakeholders could have some chance of a positive outcome. A set of options was identified having a short/medium temporal scale, relatively low costs and a good prospect of being absorbed by the Triona community. These were:

‘Mineral water’ — to use some spring water

sources located in the forest to produce bottled mineral water. At the moment, this water flows free in the forest, so bottling it creates no new water use conflict.

‘Mineral water plus recreation’ — to combine

mineral water with some recreational activities (restaurant, hotel, etc.) in the forest connected with restoration of existing country houses which are property of the ‘Comune’.

‘Information campaign’ — to develop an

exten-sive information campaign about local water resources (water cycle, water process, techno-logical uses of water, water management, water distribution, …).

‘Galli law’ — the Galli framework law

con-cerns the basin authority, to be implemented by the central government. In Sicily water is ‘a reserved topic’ of the regional government, which means difficulties in implementation.

‘Self-sufficiency’ — self-sufficiency of Troina drinking water needs is a major short-term goal of the town administration in its water policy.

‘Compensation’ — compensation to Troina

(for the fact that water is appropriated outside the community).

‘Changes to irrigation’ — investments in the

water irrigation structure in Catania (pipelines,

etc.) could improve the efficiency of the water use by Catania farmers, thus saving more water for Troina.

For the evaluation of these options, several ana-lytical methods were employed in a complemen-tary way (see Funtowicz et al., 1998, 2000; De Marchi et al., 2000).On the basis of an initial institutional analysis, it was chosen to construct a multi-criteria analysis framework centred on the identification of the key interest groups. By con-sidering appropriate criteria and alternatives, it was then possible to take into account the confl-icting preferences of these groups. An impact score system was devised, and an evaluation (or impact) matrix constructed. The scores were then analysed by applying discrete multi-criteria tech-niques (the NAIADE method) so that a partial ranking of policy options was obtained.

It was made clear from the outset of the study that the multi-criteria evaluation techniques were not expected to solve the conflicts or uncertainties about Troina water use options. Rather, they can help to provide insight into the nature of conflicts and into ways of exploring policy compromises (or policy solutions that could have a higher degree of equity on different income groups). Given the contrasting interests, this is a situation where the decision maker (the ‘Troina Com-mune’) has to decide whose interests have prior-ity; no escape from value judgements is possible. What is interesting is that the Troina community has quickly ‘internalised’ the notion of evaluation tools as vehicles for developing public discussion and policy debate. They have spontaneously gone beyond the idea of multi-criteria evaluation as a mechanical process of ranking, and have inte-grated the study perspectives and results within their own political process.

3. A methodological reflection

policy. Each of the subsequent papers, by mem-bers of the respective case study team, provides a discussion based around an individual case study. All the empirical work has been comprehensively reported elsewhere (the various papers provide a full documentation), so the paper authors build on the acquired base in order to offer insights into valuation research methodology.

It can be wondered what type of comparative or general conclusions can emerge from so varied a smorgasbord of empirical and analytical starting points. This brings us to try to define the specific-ity of the VALSE project. One important theme in policy analysis and in the academic valuation literature is the ‘transferability’ — or not — of valuation results and of experience with methods, from one situation to another. TheVALSE stand-point is that analytical tools are best to be consid-ered as ‘aids’ in a social process of defining problems and considering possible solutions, but that neither quantitative results nor implementa-tions of analytical methods should be regarded as easily transferable.

Relevant to any social process of environmental valuation, there are ‘internal’ scientific criteria of validation appropriate for each tool and concep-tual framework of enquiry, and there are alsothe

‘external’ social context considerations such as the political and cultural circumstances of the en-quiry. These internal and external dimensions cannot be held completely apart from each other because ethical, cultural and political convictions, along with economic interests, can actually bear on conceptions of science itself — and at any rate will have some bearing on perceptions of the adequacy of a particular scientific or social scien-tific method for addressing the various ecological, social and economic dimensions of a problem.

But — and this is what may differentiate us from some more traditional neo-classical col-leagues — the ‘external’ considerations should not be reduced to a mere coloration of the ‘inter-nal’ methodological considerations defined by an a priori axiomatic choice. (Put simply, no, we do not go along with the postulate, neither methodo-logically nor ontomethodo-logically, that ‘everything hap-pens as if’ all human beings are, were, or would have liked to have been, rational maximising fools).

In each of the four VALSE case studies, the research design and implementation has hinged on hypotheses about and discovery of the mean-ings attached to the enquiry by the various sectors of the society concerned. This reflects the

underly-ing VALSE research objectives and

methodologi-cal choices:

First, the desire was to understand the ways that the concerned populations (or stakehold-ers) themselves express the ‘values’ of environ-ment. So the research was conceived as a process of discovery, not to be limited by ax-iomatic constrictions of a particular method’s own terms of reference.

Second, the intention was to present results in a way that maximised their pertinence to the communities and policymakers involved. This means that concern for scientific rigour and clarity in communication was not enough, but also attention had to be paid to the significance of the results and arguments for the actors concerned, as seen in their terms.

TheVALSE case studies all offered opportunities

to evaluate the hopes that might be placed in particular methods or tools as a means of obtain-ing information on the values that concerned individuals and populations attach to features of their environments. In this way, the ambitions, limitations, justifications and weaknesses of differ-ing perspectives and practices of evaluation have themselves been reflexively presented and ap-praised. More particularly, the political as well as scientific significance of methodological choices has been brought into focus, showing how method choice, implementation and communica-tion of results can — and should — all be made elements of deliberation within wider social processes.

Acknowledgements

The VALSE project has been a successful

go-ing far beyond the VALSE project itself. The researchers of the project teams would like to express their appreciation and thanks to all per-sons, of whatever academic, bureaucratic, public-spirited, self-interested or other persuasions, for their contributions to the research process. We also express thanks to the referees of the various papers who, individually and collectively, have contributed significantly to the clarity of the anal-ysis and arguments presented here.

Appendix A. Documentation of the VALSE Project

A full presentation of The VALSE Project re-sults and documentation (published papers, un-published research reports, etc.) can be obtained in the following two forms:

The VALSE Project Website (edited by Serafin Corral Quintana) http://alba.jrc.it/valse.html. This web-site contains the complete Full Final Report of The VALSE Project, Social Processes for Environmental Valuation, as prepared for the DG-XII, European Commission, under contract ENV4-CT96-0226 (Report EUR 18677 EN, ed-ited by Martin O’Connor, published by the Eu-ropean Commission Joint Research Centre, Ispra, Italy, September 1998). The site also includes selected other project products and documenta-tion, together with links to related sites.

Walking in the Garden(s) of Babylon: an overview of the VALSE Project, C3ED Research Report composed by Martin O’Connor, published by the C3ED, Universite´ de Versailles-Saint Quentin en Yvelines, Guyancourt, France, Sep-tember 1998. This 40 A4-page three colour profes-sionally published document is designed as a research and teaching resource. For further infor-mation and prices for individual or bulk pur-chases, see the VALSE web-site or contact the C3ED (E-mail: [email protected]).

Appendix B. The VALSE Project partner institutions

Centre d’Economie et d’Ethique pour

l’Envi-ronnement et le De´veloppement (C3ED), Univer-site´ de Versailles-Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France. Team Leader (and Project Coordinator): Martin O’Connor. Other C3ED Team Members: Jean-Franc¸ois Noe¨l, Jessy Tsang King Sang. With contributions also from: Vale´rie Boisvert, Christophe Heron, Jean-Marc Douguet. Sub-con-tractors: Yann Laurans (AscA) and Olivier Go-dard (CIRED), France.

Departemento de Economia Aplicada, Univer-sidad de La Laguna (ULL), Tenerife, Canary Islands Spain. Team Leader: Federico Aguilera Klink. Other Team Members: Juan Sanchez Gar-cia, Eduardo Pe´rez Moriana.

Institute for Systems, Informatics and Safety (ISIS), EC Joint Research Centre, Ispra (JRC) Italy. Team Leader: Silvio Funtowicz. Other Team Members: Bruna de Marchi (Institute of International Sociology of Gorizia), Silvestro Lo Cascio (Comune di Troina), Giuseppe Munda (Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona). Plus con-tributions by: Rosa Rossi, Maura Del Zotto, Gio-vanni Delli Zotti, Gabriele Caputo, Antonella Casella, Salvatore Costantino, Giuseppe Pap-palardo, Irene Trovato Menza and Silvestro Vi-tale, Serafin Corral Quintana, A. ngela Guimaraes Pereira, Francesca Di Pietro, Jerry Ravetz, Giuseppe Rossi.

Lancaster University Centre for the Study of Environmental Change (CSEC). Team Leader: Allan Holland (Department of Philosophy, Lan-caster University). Other LanLan-caster Team Mem-bers: John O’Neill, Robin Grove-White, Jonathan Aldred, Michael Jacobs, with contributions from John Foster and Brian Wynne. Major subcontrac-tor: Clive SPASH, Cambridge Research for the Environment , University of Cambridge, Eng-land.

References

Aguilera Klink, F., Pe´rez Moriana, E., Sa´nchez Garcı´a, J., 1997. Procesos sociales para la valoracio´n ambiental. El caso del agua en Tenerife (Islas Canarias), Working Paper, University of La Laguna.

Doc-umento de trabajo 97/98-16, Departamento de Economı´a Aplicada, Universidad de La Laguna, Canary Islands. Aguilera Klink, F., Pe´rez Moriana, E., Sa´nchez Garcı´a, J.,

2000a. Social processes for environmental valuation. The case of water in Tenerife (Canary Islands), Ecological Economics, 34(2) 233 – 245.

Aguilera Klink, F., Pe´rez Moriana, E., Sa´nchez Garcı´a, J., forthcoming 2000b. Social processes, values and interests: environmental valuation of groundwater in Tenerife (Ca-nary Islands), International Journal of Environment and Pollution, 13(4).

Aldred, J., Jacobs M., 1997. Citizens and Wetlands: What priority, if any, should be given to the creation of wetlands in the fens?, Report of the Ely Citizen’s Jury, Centre for the Study of Environmental Change (CSEC), Lancaster University, Lancaster, September 1997, 40 pp.

Aldred, J., Jacobs, M., 2000. Citizens and wetlands: evaluating the Ely citizens’ jury, Ecological Economics, 34(2) 217 – 232.

Boisvert, V., Noe¨l, J-F., Tsang King Sang J., 1998. Le Bois de Bouchereau: re´sultats d’une enqueˆte aupre`s des propri-e´taires, Rapport de Recherche, C3ED, Universite´ de Ver-sailles-Saint Quentin en Yvelines, Guyancourt, Mai 1998, 40 pp.

De Marchi, B., Funtowicz, S.O., Lo Cascio, S., Munda, G., 2000. Combining participative and institutional approaches with multicriteria evaluation. An empirical study for water issues in Troina, Sicily, Ecological Economics, 34(2) 267 – 282.

Funtowicz, S.O., De Marchi, B., Lo Cascio, S., Munda G., 1998. The Troina water valuation case study, unpublished Research Report prepared by ISIS, European Commission Joint Research Centre, Ispra, Italy.

Funtowicz, S.O., Lo Cascio, S., Munda, G., 2000. The Troina perceived water issue: a multicriteria evaluation process. In: O’Connor, M. (Ed.), Environmental Evaluation, vol. 1 in the ILEE series (International Library of Ecological Economics). Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK/ Northampton, MA, USA.

Heron, C., 1997. La repre´sentation syste´mique de l’ilot boise´: vers une mise en evidence de la valeur sociale. Revue Internationale de Syste´mique 11 (2), 147 – 175.

Noe¨l, J.-F., Tsang King Sang, J., 1997. Le Bois de Bouchereau: des perceptions sociales a` la mise en perspective de la valeur, Cahiers du C3ED no 97-01, Universite´ de Versailles-Saint Quentin en Yvelines, Octo-ber 1997.

Noe¨l, J-F., O’Connor, M., Tsang King Sang J., 2000. The Bouchereau Woodland and the transmission of socio-eco-logical economic value, Ecosocio-eco-logical Economics, 34(2) 247-266.

O’Connor M., Heron C., 1999. Forest value and the distribu-tion of sustainability: valuadistribu-tion concepts and methodology in application to forest islands in agricultural zones in France, Proceedings of the International Symposium on ‘Non-Market Benefits of Forestry’ sponsored by the Forestry Commission of the UK, Edinburgh, Scotland, 24 – 28 June 1996.

Spash, C., 2000. Ecosystems, contingent valuation and ethics: the case of wetland recreation, Ecological Economics, 34(2) 195 – 215.

Spash, C., Holland, A., O’Neill, J., 1998. Environmental Val-ues and Wetland Ecosystems, CVM, Ethics and Attitudes, Research Report by Cambridge Research for the Environ-ment, Cambridge University.