Generational Changes. Oxford: Peter Lang.

“Lost” (and Found) in Transculturation. The Italian Networked Collectivism of US TV Series and Fansubbing Performances

Agnese Vellar

University of Torino – Italy agnesevellar@gmail.com

1 Television Audiences in Networked Publics

The internet has evolved since the late 1990s from text-based technology to the multimedia and visually communication technology of today. During the 1990s, television fans adopted social media such as Usenet newsgroups to communicate with like-minded people, thus participating in the construction of audience community of practice (Baym, 2000). In the 2000s the reach of the extended to a much broader public and social media such as web forums, blogs and social network sites became popular among young people. Adopting and adapting social media, young people are now participating in the construction of networked publics (Ito, 2008; boyd, 2008) that are both digital social spaces and imagined communities. These technological and social changes are affecting the way television fans consume media products, communicate with like-minded people and participate in the construction of collective identities. In fact, fan cultures are evolving from site-based communities to a networked collectivism (Baym, 2007).

2 Generations of Fandom: from Cultural Dupes to Networked

Amateur Experts

Fans are consumers with an intense engagement with a mass media product. For a long time they have been represented as cultural dopes both by mass media and by social researchers. This negative view of fans is a result of the moral dualism which exists between the high-taste and rationality of the intellectual élite and the perceived low-taste of fans (Jenkins, 1992). The academic view of fans as deviants changed during the 1990s when Jenkins proposed conceptualizing fans not as isolated people, but as productive consumers in-volved in creative and collaborative social practices that are part of a participa-tory culture. Then Baym (2000) and Hills (2002) conceptualized communi-cative and productive practices of fans as performance from which emerges communities and cultures. However, the way fans participate in the construction of digital social space and collective identities is evolving with the rapid changing of the technological and media environment. In the evolution of television participatory culture three different generations can be identified: (i) the subcultural fandom of the 1980s, (ii) the online fan groups of the 1990s, and (iii) the networked collectivism of the 2000s.

2.1 Conceptualizing Fan Practices: from Textual Poaching to

Performances of Fan Audiencehood

Textual Poachers by Henry Jenkins (1992) is considered to be the book that launched fan studies – an academic field that investigates fan practices from an ethnographic approach and that contributed to the re-conceptualization of media fans as productive consumers. In Textual Poachers Jenkins describes a television subculture that emerged around sci-fi TV series. Jenkins defined fans as textual poachers because they appropriate professionally produced television text and create derivative works such as fanfiction and fanvids that expand the narrative universe, often with alternative meanings. Jenkins thus focused on the fans’ relations with the media text and conceptualized the amateur production as a form of resistance to the media industry. Studying the online fandom that emerged in Usenet newsgroups in the early 1990s Jenkins re-conceptualized fans as textual hackers, leaving behind the oppositional interpretation and focusing more on the pleasure fans experience in decoding complex series such as Twin Peaks, which satisfies their need for cognitive control over the text.

Generational Changes. Oxford: Peter Lang.

dimension, Hills describes online fan practice as self-performance of audience-as-a-text. Online fans are textual performers that compete and collaborate to acquire (i) cultural capital (skills, knowledge and distinction), (ii) social capital (a network of friends, acquaintance, and professionals) and (iii) symbolic capital (fame, accumulated prestige and legitimation of other conjunctions of capitals). In performing their fan audiencehood they gain pleasure reliving the cathartic moments previously experienced during the fruition of the original text, and, at the same time, they create a second order of text that other fans can consume.

Fan studies of online groups describe how a techno-élite of educated people with a particular interest in mass media contents adopted mediated technologies as the Usenet newsgroups to discuss, pool perspectives, share knowledge and collaboratively analyze text. The online social interaction between fans can be interpreted as performance of fan audiencehood that a public of lurkers can con-sume and from which collective identities can emerge.

2.2 Productive Consumers in the Networked Publics: a Collectivism

of Amateur Experts

In the 2000s, the internet and television converged in a cross-media platform where corporations distribute transmedia storytelling intended to involve con-sumers in a narrative universe (Jenkins, 2006a). At the same time youth and young adults of the post industrial countries are adopting a new generation of social media such as Facebook, MySpace, Twitter and YouTube, known as Social Network Sites (SNSs) (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). Youth use social media to keep in contact with friends (hang out), experiment with new form of learning and self-expression (mess around) and connect with like-minded people in interest-driven networks (geek out) (Ito, et al., 2009). Young adults use Facebook1 to keep in contact with old friends and acquaintances and thus

crystallize ephemeral relationships and accumulate social capital (Ellison, et al., 2007). Television fans publish self-produced and derivative works in content sharing sites such as YouTube2 or deviantArt3, thus competing with

professionally produced media texts. The quality and the amount of amateur content raise a debate on the legitimacy of amateur work and, at the same time, on the possibility to capitalize on it. In fact corporations aim to create brand communities and stimulate amateur production that promotes the brand itself. At the same time mass media present audience productivity as a form of piracy because consumers appropriate copyrighted material to create derivative works.

Fan groups are adopting SNSs thus evolving from site-based communities to a networked collectivism (Baym, 2007) of amateur experts (Baym & Burnett, 2009). A networked collectivism emerges around one or multiple texts and is

distributed throughout a variety of offline environment and online sites, which may be amateur blogs, profiles in SNSs or professional web portals. Through creating amateur content and participating in a networked collectivism fans promote their media passion. However, they don’t ask for economic reward because they are satisfied by other kinds of reward which are social (relationships that can be of use for future career opportunities) and cultural (discovery of new content). The networked shape of fan groups raises many issues concerning the coordination, the coherence and the efficiency of the productive and communicative practice of fans. However, SNSs give fans many opportunities to share multimedia material and keep in contact with other fans in a global digital environment. In cross-media platforms transcultural flows of amateur and professionally produced content are emerging. Consumers thus have access to popular content produced in different countries and can develop new forms of cultural competences, which have been defined as pop cosmopolitanism (Jenkins, 2006b). Contemporary research on television audiences should thus investigate the risks and the opportunities raised by the changed relationship between media industries and productive consumers, by the adoption of SNSs by fans, and by the emergence of a global interactive environment where audiovisual content flows across nations.

3 Italian Audiences, US TV Series and Networked Publics

Generational Changes. Oxford: Peter Lang.

complex TV series such as Lost. In fact Lost was intentionally designed with a complex plot and narrative hooks, with the aim of involving internet users in an intellectual challenge and engaging television consumers in continuative and repeated viewings (Askwith, 2007). Italian fans can’t wait for national networks to broadcast dubbed episodes and so they download original episodes as soon as the US crew share it on p2p networks. Since many Italian fans don’t understand English well they use amateur subtitles (fansubs or subs) produced by fan groups such as Subsfactory4 and ItaSA5. These fan groups are hierarchically

organized volunteer communities that produce derivative works such as amateur subtitles (fansubs) and thus Italianize US fiction and work as mediators for the Italian audience (Barra, 2009). Fansubbers can be defined as amateur experts because they are involved in a time-consuming activity and because they are de-veloping professional expertise without earning anything from their work. Italian professionals started to capitalize on the skills of fansubbers to produce professional content without always acknowledging their contribution6. In the

Italian mediascape the relationship between professional and amateur culture is evolving and should thus be investigated. To better understand the role of the fansubbing community from the perspective of the fans themselves I conducted ethnographic research on the Italian participatory culture that emerges around US TV series. After an explorative research on the Italian networked publics I studied the ItaSA community with the aim of investigating (i) the role of amateur activity in the life of the most enterprising fans and (ii) the emergence of collective identities in Italian networked publics.

3.1 An Ethnographic Study of the Italian “Starring System”

My study focuses on how participatory culture in networked publics can be understood as a starring system – a network of individual and collective performances of fan audiencehood. In the starring system fans compete, collabo-rate and remix cultural material in order to gain visibility and acquire social and cultural capital. In performing fan audiencehood on networked publics fans produce a second order of audiovisual text that can be consumed by an invisible and potentially broad audience. Focusing on the social dimension of fan culture makes it possible to describe how Italian audiences participate in the

4http://www.subsfactory.it/ 5http://www.italiansubs.net/

6 For example MTV Italia co-opted subbers to produce subs for videos shared on the online

construction of a contemporary media environment and negotiate their role with the media industry.

To investigate Italian participatory cultures I conducted a 20month ethnographic study (March 2008 - November 2009) of networked publics focusing on the linguistic imagined community of Italian speakers and, in particular, on the community of ItaSA. I combined a multi-sited participant observation and a computer aided qualitative content analysis of multimedia texts. Since I conducted the participant observation on the social context where the members of ItaSA interact, the research field changed with the evolution of the community. In the first few months I interacted mainly in the forum and on the online chat platform. Some of the members then started to use also Facebook and Twitter7, so I extended my participation to include those SNSs too. My data

consists of digital content produced by fans or co-produced with media professionals – online text conversations, hypermedia online profiles, audiovisual fanart, magazine and online articles, radio and TV programs. Because the quantity of data was so great, I used computer-aided qualitative data analysis software –NVivo – to analyze the material where the members of ItaSA perform their fan audiencehood. I then conducted biographical interviews with 12 of the most participative members of the community (6 male and 6 female) to understand the role of their amateur activity in their personal lives.

3.2 Transnational Fansubbing as Performance of Pop

Cosmopolitanism

ItaSA is the biggest Italian fansubbing community – a demanding and time-consuming fan practice that involves a team of subbers in the production of Italian subtitles for US TV series. The team is of three to five subbers and an editor taking the role of coordinator create the final version of the sub, a textual file which is published on the web portal8. The ItaSA community was created in

December 2005 by Klonny, a 17-year-old boy who discovered Legendaz, a fansubbing community producing Portuguese subs for Brazilian audiences, whilst surfing the web in search of information about his favourite TV series. Klonny then contacted other fans that he had met on various Italian forums and set up a team of subbers to produce the subs for Lost, Smallville, Supernatural, Joey, Charmed, and C.S.I.. At that time their main aim was to release subs as soon as they could, partly as a challenge to the other Italian fansubbing community, Subsfactory, so since it is easier and therefore faster for Italian subbers to translate from Portuguese rather than from English, they worked from the Portuguese versions created by Legandaz.

Motivated by the challenge to produce subs quickly, they then developed their

7 http://twitter.com/

8 Subbers only publish textual files containing subtitles on the portal. The portal has no

Generational Changes. Oxford: Peter Lang.

language skills by learning both English and Portuguese and started to collaborate with fansubbing communities in such countries as France and China. Thanks to word of mouth, other fans asked to collaborate, partly with the aim of developing their language skills but also for the gratification from the productive practice itself. Subbers enjoy creating Italian dialogues because they feel as if they are closer to their favourite characters and, at the same time, they can express their creativity by personalizing the original dialogues. The small group of fans evolved into a hierarchy of 1999 who have produced the subtitles for 250

TV series, anime and independent movies (7 Admins, 19 Seniors, 16 Publishers, 80 Traduttori10, 68 Traduttrici, and 9 Synchers11). Most of the staff are young

adults, in particular university students from computer science and communication faculties. Subbers with the role of admins are more technologically oriented and developed a web portal with a graphical homepage and Web 2.0 functionality, in this case a recommendation system and a personalized interface which works like an amateur program schedule that Italian fans can use to choose content to watch. The portal integrates a wiki with a collaborative television encyclopaedia, a collective blog where fans publish news, spoilers and their own reviews. When the fan group evolved into a larger staff, subbers started to care more about the quality of the subs and to spend time not just on the translation of the original dialogues but also on the adaptation of the textual and cultural references that the US TV series contains. Since subbers are first and foremost fans, they know the characters and the storyline of the series better that many professional adaptors. However, an episode of a TV series may also contain numerous references to American culture, e.g. the youth culture of teen dramas such as Gossip Girl, the geek culture of The Big Bang Theory or the lesbian culture of The L Word). To adapt terms that come from the pop US cultures they make use of online collaborative resources, for example slang dictionaries such as Urban Dictionary12 or wiki encyclopaedia such as

Wikipedia13 or Lostpedia14.

Collaborating as amateurs, the staff members have accumulated linguistic capital (English and Portuguese comprehension skills), social capital (that of

9 Quantitative data related to the staff are updated to November 2008, three years after the

creation of ItaSA.

10 Traduttori is the Italian for male subber, while Traduttrici is the Italian for female

subber. It is interesting to note both that a gender difference is made clear and that the roles are defined in Italian. Staff members prefer to use the Italian Traduttori and Traduttrici rather than the English subbers.

11 A syncher creates different versions of the sub to adapt it to different versions of video

files that circulate on p2p network.

friendships with fans from different Italian local communities, online relationships with other fansubbing communities and acquaintances with national professionals) and cultural capital (i.e. textual knowledge about plots and characters of specific TV series, intertextual knowledge about specific genres and extratextual knowledge about the culture that is depicted in a series). Subbers’ accumulation of capitals has led to a growth in their popularity within Italian networked publics: the ItaSA community has grown to total of 155.39215

users. Subbers are now recognized as experts by fan cultures and by mass media16. They are thus motivated to spend time producing subtitles not only by

the symbolical capital they gain but also by the gratification of re-enacting the actors’ performances in their favourite series. The productive practice of fansubbing could thus be interpreted as a performance of pop cosmopolitanism that allows fans to relive the cathartic emotion of the viewing and to perform their cultural competences. Since some subbers have become micro-celebrities in networked publics they also function as role models thereby stimulating younger fans to get involved in productive activity. In 2009 at least 30 fans a week asked to become subbers. To maintain the quality of the subs the staff thus developed a formal process of selection and tutorship. Fans must first pass a subbing test, after which they become Traduttori junior, and then after a trial month of demonstrating their commitment they officially become Traduttori. Editors monitor the quality of the work of the members of their team, assessing their ability in English comprehension, Italian writing and the use of editing softwares such as VisualSubSync which have been adapted to produce subs.

In four years ItaSA evolved from a small group of fans to an online hierarchi-cal organization with a formal education system and an interdisciplinary staff. At the same time the forum evolved into a Web 2.0 web portal. When the community became popular the professionalized subbers struggled to reconcile the amateur ethos that motivated them to participate in a fan community in the first place with the highly structured organization that ItaSA became. Because of that some seniors attempted to involve the new subbers in an online social life so as not to lose human contact during an highly formalized online productive process. Some subbers, however, left the community because it had lost its original amateur ethos. In Klonni’s case, four years after he founded ItaSA, he decided to leave because he was beginning to acquire morals more common in a multinational, and then founded Stubborn Italian Jackass17, a new fansubbing

portal. This could be interpreted as a step in the evolution of the Italian

15 Quantitative data concerning the community are updated to 1st December 2009, four

years after the creation of ItaSA.

16 ItaSA has been described as an amateur community of experts in the mobile tv program

SpoilerTv (La3Tv), in webradio shows such as Versione Beta and Dispenser (Radio2), in national magazines such as Wired Italia and in national tv programs such as Sugo (Rai4).

Generational Changes. Oxford: Peter Lang.

fansubbing system from a duopoly to an oligopoly. However, we should remember that the forms of capital exchanged in this marketplace don’t produce monetary compensation – they lead instead to social relationships and transcultural flows from which collective identity emerges.

3.3 Constructing Identity in Networked Publics: ItaSA, Itasiani and

their Audiences

ItaSA is an online platform but at the same time it is a social space where two different collective identities have been constructed: the official and multi-sited identity of ItaSA and the emergent and networked identity of the Itasiani. The official identity of ItaSA has been constructed by the staff in the media, in the web portal and in the official SNSs profiles. In the media they present themselves as a generational audiencehood stimulating an identification process in the young Italian audiencehood18. To differentiate themselves both from

digital piracy and from the professional cultures they stress the fact that they don’t get paid for their work. At the same time they distinguish themselves from regular fans because of their high involvement in both analytical and productive activity. Furthermore, they visually present themselves as a professionalized community. In fact the portal was designed with a Web 2.0 aesthetic with the aim of looking like a professionally produced site. To reconcile their amateur ethos and their professional competences they present themselves with performance of humor (Baym, 1995). For example they define the time that they spend producing subs as wasted hours and when asked why they work free they regularly answer «we’ve got a screw loose»19. ItaSA uses also SNSs to publicize

their activity. They created a Facebook group20 and a Twitter account21 to keep

fans updated with the latest released subs and the latest published blog entries. The ItaSA Facebook group has 10.755 subscribers posting wall to wall expressing their gratitude for the amateur work of the subbers and also complaining when they are not fast enough to release the subs.

In the media, in the official SNSs profiles and on the portal the ItaSA staff perform their official identity in front of an audience of fans that consume their products. However, the staff also developed social spaces inside the portal with

18 In the pilot of SpoilerTv’s mobile Tv show, ItaSA introduce the show with these words:

«Who among us who grew up during the 80s can say they never watched their favourite tv series like MacGyver or Hazzard in the morning when skipping school?». The staff creates threads in the forum to share memories of their first television passions experienced during the 1990s.

19 These expressions are English translations of the Italian «ore perse» and «ci manca

qualche venerdì». I asked them to translate the sentences for this article since they use them to present themselves.

the aim of involving users in participatory activities. The portal integrates chat channels and a forum with 1.493.236 posts and 51.010 threads structured in 32 thematic boards. The forum is moderated by the most participative users, who take on the official role of Moderator and coordinated by a Senior (a subber with an organizational role). Informative and interpretive practices are performed in the forum using both Italian and English. In fact users share English information (sometimes translating it into Italian) and comment in Italian on TV series but integrating English words and slang expressions learned while watching TV series22. Chat channels have been created by subbers to collaborate in real time

for the production of subs. However, users also join them to hang out with other fans. Since 2008 Facebook has been adopted by a broad Italian population and a linguistic imagined community has emerged. ItaSA users adopted Facebook to communicate with fans that they met on the forum. In Facebook fans communicate in Italian while in Twitter they also use the English language since Twitter is still not perceived as a national community. The subbers use their Facebook personal profiles to notify the community when new subs are released, to share organizational information with other members of the team and also to comment on the TV series that they are watching. Subbers also create Skype collective video calls to watch episodes together. Finally subbers organize official offline meetings at least once a year, while people in particular geographical areas (such as Milan or Rome) meet each informally other more often.

From the ongoing interaction between staff members and the users in different online and offline sites there emerged (i) a sense of belonging that characterizes the broad collective identity of the Itasiani (as they call themselves), (ii) interpersonal relationships between the staff members that evolved into offline local tight-knit groups and in romantic relationships and (iii) online friendships between users that are maintained through different social media. The Itasiani are thus a collective identity that emerged in an online forum and that is now distributed in multiple SNSs and offline environments and that has a central role in the broader networked collectivism of US TV series.

4 The Pop-Élite and the Transcultural Networked Collectivism

In this paper I’ve described the emergence of a networked collectivism of TV fans who adapt a cross-media platform and produce flows of derivative contents that are consumed by a national generational audience. In the networked collectivism I’ve observed two main different forms of participation: (i) the adoption of p2p networks and social media by a generational audience to fulfil

22 For example Italian fans integrate the term “XOXO” (hugs and kisses) in their online

conversations because they have picked it up from watching the teen drama Gossip Girl. It was used by US young people in online and mobile messages and then incorporated into the

Generational Changes. Oxford: Peter Lang.

their entertainment needs and (ii) the collaboration between individual fans and fan groups who are adapting both digital technologies and professionally pro-duced fictional contents. Italian fans adopt Skype, Twitter, Facebook, chats and forums to communicate with peers and other fans. Interacting in those environ-ments they hybridize Italian with the English language and with cultural references to US TV series thereby constructing a symbolic system that works as a common ground for an Italian generation that doesn’t identify itself with the previous television generation that emerged around the Italian broadcasting system. The most enterprising fans spend time selecting, translating and adapting US TV contents. Collaborating online they construct new social structures such as translocal friendships, fan groups and hierarchical organizations such as ItaSA.

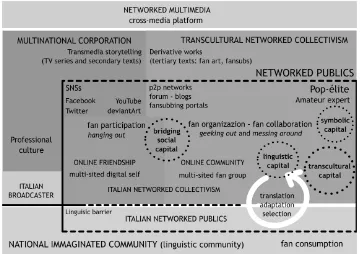

Figure 1: Italian collectivism in the networked multimedia (image created by the author)

Participating in the networked collectivism fans acquire (i) linguistic capital to translate foreign content for the Italian linguistic community, (ii) transcultural capital (knowledge and skills about foreign products and cultures; distinction from preceding Italian generations) which they use to create amateur products that appeal to a pop cosmopolitan generation, (iii) bridging social capital to de-velop relationships with other Italian and foreign fans and (iv) symbolic capital acquired from popularity on networked publics and, at the same time, legiti-mization by the mass media. They could thus be defined as a pop-élite of amateur experts who are adapting the networked multimedia to fulfil their personal needs as fans, thus producing an entertaining platform that an Italian generational audience is adopting (Figure 1). At the same time they work as role models for younger fans who are thus stimulated to get involved in collaborative activity.

Generational Changes. Oxford: Peter Lang.

for younger fans. We should thus investigate the educational opportunities that are emerging in fan groups, with the aim of understanding how the creation of derivative content could enhance youth media literacy and cultural competences and whether collaborative project around pop culture texts can be applied in traditional educational contexts.

5 Bibliography

Aroldi, P. & Colombo F. eds., 2003. Le Età della tv. Indagine su Quattro Generazioni di Spettatori Italiani. Milano: Vita e Pensiero.

Askwith, I.D., 2007. Television 2.0: Reconceptualizing TV as an Engagement Medium. Masters thesis. Boston: MIT.

Barra, L., 2009. The Mediation is the Message: Italian Regionalization of US TV Series as Co-creational Work. International Journal of Cultural Studies. 12(5), pp. 509-525.

Baym, N. K., 1995. The Performance of Humor in Computer-Mediated Communication. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, [Online] 1(2). Available at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol1/issue2/baym.html [Accessed 03 April 2008].

Baym, N. K., 2000. Tune in, Log on: Soap, Fandom, and Online Community. Tousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Baym, N. K., 2007. The new shape of online community: The example of Swedish independent music fandom. First Monday, [Online]. 12 (8). Available at:

http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1978/185 3 [Accessed 27 October 2009].

Baym, N. K. & Burnett, R., 2009. Amateur Experts: International Fan Labor in Swedish Independent Music. International Journal of Cultural Studies. 12(5), pp. 1-17.

boyd, d. & Ellison, N., 2007. Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, [Online]. 13(1), Art. 11. Available at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/boyd.ellison.html

[Accessed 15 October 2008].

boyd, d., 2008. Taken Out of Content. American Teen Sociality in Networked Publics. Ph. D. Berkeley: UC - Berkeley. Available at:

http://www.danah.org/papers/TakenOutOfContext.pdf [Accessed 21 December

2008].

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, [Online]. 12(4), Art.1. Available at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol12/issue4/ellison.html [Accessed 04 November 2008].

Grasso, A., 2007. Buona Maestra. Perché i Telefilms sono Diventati più Importanti dei Cinema e dei Libri. Milano: Mondadori.

Hills, M., 2002. Fan Cultures. London: Routledge.

Ito, M., 2008. Networked Publics: Introduction. In: K. Varnelis, ed. Networked

Publics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Available at:

http://www.itofisher.com/mito/ito.netpublics.pdf [Accessed 15 June 2009]

Ito, M. et al., 2009. Hanging Out, Messing Around, Geeking Out: Living and Learning with New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Jenkins, H., 1992. Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge.

Jenkins, H., 2006a. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Jenkins, H., 2006b. Fans, Blogger, and Gamers. Exploring Participatory Cultures. New York: New York University Press.

J. Lull, 1995. Media, Communication, Culture: A Global Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Scaglioni, M., 2006. Tv di Culto. La Serialità Televisiva Americana e il suo Fandom. Milano: Vita e Pensiero.