Maritime Economics and Logistics

Maritime Safety and the Protection of the Marine Environment

The pressures of the Maritime Industry on the Marine Environment: how effective implementation of international regulations on maritime safety and the prevention of

marine pollution can protect the environment and sustain the global economy

William Boris Douni Kouambo

15 June 2012

Introduction

For many centuries the world’s seas and oceans have been the main transport routes for international trade. Until the invention and the modernization of aircrafts, ships were the only available carriers of sufficiently large capacity for trading across oceans. Used to transport spices, natural resources and even human lives, countries have historically thrived through the shipping trade, and it is not remarkable that even today shipping still accounts for 90% of global trade and is a prime contributor to global economic growth (IMO, 2011).

Globalization and the continuous elimination of geographic, economic and political frontiers have transformed the world into a global marketplace, where goods and services are rapidly exchanged among nations, placing increasing high demands on the need for more efficient modes of transportation. Over the past decennia larger and faster ships have been developed to meet these needs and to facilitate transcontinental business. Along with the modernization of ocean carriers, and contributory factors such as increasing demand for raw materials, energy (oil and coal), consumer goods and essential foodstuffs; global sea traffic has risen substantially (Adolf & Wilsmeier, 2012).

Although maritime transport plays a key role in the economic and political development of many countries, it also has several negative side-effects. Set against land-based industries, shipping is comparatively a minor contributor to marine pollution, however it is still shown to adversely affect marine and land environments in a number of ways. Pollution by maritime activities can take place through the spillage of oil, sewage and refuse into the sea and also through emissions pollution to the air, which can come back in the seas by acid rain. Furthermore, ships can carry invasive plant and animal species, and proliferate the spread of human diseases – Columbus for example was accused of bringing ‘European’ diseases such as the flu, measles and small pox to the Americas. Nowadays, ballast water forms a significant threat to ecosystems, human health and economic growth by disposing invasive aquatic species across the oceans (IMO, 2011). Further dangers for the marine environment are posed by shipping accidents. Several times a year media reports depict news of tanker accidents that result in oil spills leading to the loss of sea life, destruction of fragile aquatic ecosystems, as well as the impacts on the livelihood of the people living in and from these ecosystems.

safety. Maritime safety entails the regulations, management and technology development of all forms of maritime transportation to protect life, property and the environment (IMO.org, 2012).

The central tenet of this paper argues that investing in improvements in maritime safety, through enforcement of international regulations and the implementation of conventions on maritime safety and the prevention of pollution from ships, results in greater protection of the marine environment, provided that the regulations are implemented accurately. This paper first describes the various pressures that the maritime sector poses on the marine environment. Subsequently, it discusses how the implementation of the SOLAS and MARPOL conventions can help in protecting the environment. This paper will pay special attention to the adequacy of the implementation of these international regulations, showing that if the regulations are not strictly implemented, both the marine environment and the local communities reliant on the marine ecosystems suffer adverse impacts.

I - Pressures of the shipping industry on the marine environment

The transport sector is very much dependent on the world’s oceans and seas to carry goods across continents. However, these activities cause significant pressures on the marine environment. 77% of the marine pollution can be linked to human activities. The maritime sector only contributes 12% to the overall global marine protection (Marisec.org, 2012). This might be a small number; but it still causes several important pressures on the marine environment which are identified and discussed in the following paragraphs:

a) Invasive Species

In the context of an increasingly globalized world, where markets are becoming less restricted by economic and geographical boundaries, overcoming competition relies heavily on reducing transportation times of global supply chains. This requires shortening or eliminating steps in the global chain that do not demonstrably add value to the product. Advances in shipping technology have contributed tremendously to speeding up the movement of goods and people across distant locations (MacPhee, 2006). New technologies have ensured that ships can move faster, while simultaneously carrying more ballast, creating logistical changes and challenges that pose risks to the marine environment.

they turn out to be predators for native species or when they take over their natural habitats. In the worst scenario the new species cause the extinction of the native species. Invasive or ‘alien’ species are considered to be the main contributing factor in the classification of 35 to 46 percent of species on the endangered species list (MacPhee: 2006).

Studies have also demonstrated the financial impact of invasive species on the global economy. According to Cangelosi (2002-2003: 69), it is estimated that the United States alone have recorded damages by alien species for an amount of $100 billion. One can therefore imagine the global financial burden faced by many countries in addressing the prevention, control and elimination of non-native species. In her article “Alien Flotillas: The Expansion of Invasive Species through Ship Ballast Water”, MacPhee (2006) demonstrates the impact of invasive species on communities whose survival heavily depends on resources from their direct habitat. The consequences are especially felt in poor countries; where the primarily source of income for communities living close to the sea is often through fishing. The impact of invasive species to the native

ecosystem(s) and food chains can cause a reduction, and even the eradication, of other species that might be essential to the survival of the neighboring ecosystems.

b) Plastic debris

Marine debris, defined as solid material that finds its way to the marine environment (Greenpeace, 2006), consists of waste materials derived directly from shipping activities but also from debris that comes from land-based activities. Plastic debris is one major part of marine debris. Plastic debris causes a detrimental effect on the health of numerous marine animals, birds and ecosystems. The disturbance is caused by the plastic itself which can kill animals that get entangled in it or eat it; or by toxic chemicals released by plastic in its decomposition phase. All types of boats are potential dischargers of plastic debris, originating accidentally by the loss of shipping parts, or intentionally through illegal dumping. Cans, bottles, plastics bags, pieces of polypropylene fishing net and sanitary and sewage-related debris such as diapers and condoms, are among the many types of harmful debris that end up in the oceans. According to IMO (imo.org, 2012) a plastic bottle that ends up in the sea can survive for up to 450 years. The problem with plastic debris is that it can remain unchanged for hundreds of years, while at the same time the production of plastic increases continuously. It therefore becomes extremely important to manage the production and deposition of the products (The GEF, 2011).

Annex V from MARPOL prohibits the dumping of plastics into the sea and restricts disposal of other garbage from ships into coastal waters. Signatory countries are obliged to ensure the provision of reception facilities at ports and terminals for the reception of garbage and are allowed to check the Garbage Record Book of the vessels (IMO.org, 2012). Although the global regulations on restricting the amount of plastic debris in oceans well are widely known and understood; in practice they tend to be poorly implemented by many national governments. There are various global legal instruments and voluntary agreements aimed at the prevention and management of plastic debris, both on land and sea, such as MARPOL annex V. However; preventing marine debris and addressing the impacts of marine debris is not as easy as it may seem on paper. The issue of marine debris is a global one, and extends beyond the jurisdictional authority or ability of any single institution or country to address. Furthermore, there is a lack of economic and financial incentives for companies and countries to address the debris. There are even perverse incentives for big upstream producers to pass costs on to individuals or nations that are excessively impacted by marine debris in comparison to any economic benefits they may obtain (The GEF, 2011). The impacts of this lack of regulatory adherence are often felt disproportionately by those least equipped to protect themselves, such as poor coastal communities and marine animals and birds.

c) Waste Dumping

Another pressure from which the marine environment suffers and which is directly linked to shipping activities across oceans is waste dumping. For the purpose of this paper, waste dumping is defined as the deliberate disposal of wastes from ships and it does not include land-based activities or accidental discharges (Greenpeace, 2006). Two types of waste dumping by ships are highlighted here: waste dumping by cruise ships and the dumping of hazardous goods in poor countries.

As mentioned earlier, sea traffic over the past few years has been significantly increasing. While the growing global economy and population ask for more goods, creating the demand for more see traffic, additionally developed countries populations are increasingly interested in enjoying cruise-ship holidays. This increase in cruise ship holidays, while a lucrative business, is one that can pose a significant threat to the marine environment from waste dumping.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), it is now common to see a vessel carrying 3,000 passengers and crew and it has been estimated that today’s worldwide cruise ship fleet includes more than 230 ships (EPA, 2012). Generally known as floating cities, the pace at which this industry has grown and the lack of regulations governing cruise ship companies, raise questions about the environmental impact of cruise ships on the marine ecosystem.

their waste in the Garbage Record Book, however simply keeping track of waste does not mean that they are often held accountable for the waste they dispose. A problem with marine debris is that it is hard to prove which vessel is responsible for the waste dumping. With an estimated 3,000 people on board of a vessel, one can imagine the amount of waste generated by passengers and crew as quite substantial and one can also imagine the consequences when this waste is not brought back ashore but dumped in the sea. Subsequently, many solid objects, ranging from food waste to toiletry waste, become floating refuse of oceanic waters.

Moreover, in its report “Cruise Ship Wastewater Discharges” (2006) the US environmental protection agency lists many other types of waste that are usually thrown from cruise ships. These include:

- Bilge waters: water that collects in the lowest part of the ship’s hull and may contain oil, grease, and other contaminants

- Sewage and gray water: waste water from showers, sinks, laundries and kitchens

- Ballast water: fresh or salt water, sometimes containing sediments, held in tanks and cargo holds of ships to increase stability and maneuverability during transit

Cruise ships also pose a threat to the environment when accidents happen. Ships often try to get as close as possible to interesting sights risking the safety of the ship. For example, in early 2012 a cruise ship capsized of the Italian coast, causing the death of several people. Besides the loss of life, the ship polluted the water in the area endangering dolphin populations and other sea creatures living in the ecosystem (The Asian Age, 2012).

From the above it can be viewed that cruise ships are a threat to the marine environment. The danger with cruise ships is that they are not adequately held responsible for the pollution they case. Although ships coming from countries that have signed international treaties against the pollution of the oceans such as the MARPOL are obliged to obey to its rules; cruise ships seem to be finding ways to pollute without getting into major trouble. A solution for this could be not permitting cruise ships to dump any pollution in the sea and to return with waste to the harbor of the country under which flag the ship cruises. The ships should be made responsible for their adverse effects on the environment and bear the costs. Another problem with cruise ships is that they are not always following maritime safety regulations; such as the ones spelled out in the SOLAS. Companies that cause accidents that adversely affect the life of the passengers as well as the marine environment should be held accountable.

some companies found it more economical (the most evident but not only reason) to dispose waste in countries where disposal regulations are less strict and were governments are eager to make money out of accepting to deal with the toxic waste (UNECA, 2009).

Evidence of this process can be seen through the example of dumping hazardous waste by the Dutch commodity trading company Trafigura’s ship Probo Koala in the Ivory Coast. The vessel was carrying out a procedure for caustic washing on several cargoes of one such product, coker naphtha, and had to release residual waste (‘slops’).The company Trafigura selected the Amsterdam Port Services BV (APS) to take care of the treatment of the slops, but the deal was never settled since the APS increased its price for handling the slops by 3000%, after which Transfigura departed to Estonia (Transfigura, 2012). Subsequently Transfigura appointed a contractor in Ivory Coast to handle the discharged slops. Although the company believed that it made no mistake by choosing the contractor in the Ivory Coast, since the Ivory Coast had signed the MARPOL regulations, the slops were mishandled resulting in the death of a dozen of people and injuring many more. In addition to the effect it had on the victims, it had a major detrimental effect on the local and marine environment by intoxicating the waters.

The global community considers toxic dumping as an important hazard and both IMO’s SOLAS and MARPOL conventions deal with the topic. SOLAS dedicates one chapter (VII) to the rules surrounding the carriage of dangerous goods, because of the special hazards they pose to ships, persons on board and the marine environment. The carriage of dangerous goods is also covered by MARPOL Annex 2 and 3. Despite the many signatories of both conventions; and the establishment of other conventions such as the Basel Convention (Basil.int, 2012) on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, accidents with vessels carrying dangerous goods and the dumping of waste still occur too often. Mainly because the costs of disposing waste in developing countries is continuously rising and because countries can define what is meant by hazardous waste individually (INECE, 2009).

With similar malpractices as the Probo Koala case continuing, the disposal of hazardous waste by ships in developing countries remains a real threat for the environment as well as for the local population. Improved enforcement of maritime safety regulations are required to prevent incidents like the Probo Koala from reoccurrence. The incident shows that signing interventions such as the MARPOL is not necessarily enough to prevent waste dump from happening. Responsible stakeholders should be appointed, while at the same time it seems clear that countries sometimes see the economic benefits of allowing companies to dispose waste in their nation to be bigger than the costs borne by the local communities and the environment.

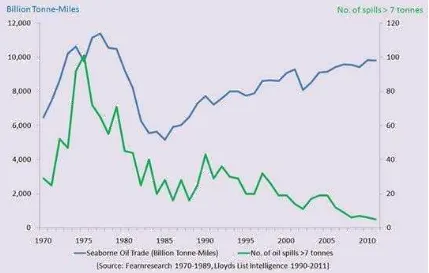

d) Oil Spills

study, Keisha (2005) mentioned that oil spills across the globe were on average 6 times higher in the 1970s. Despite the reduction in oil spills they should still be regarded as one of the most serious threats to the marine environment. Oil spills have such a detrimental effect on the marine environment since the consequences are both short term (e.g. loss of aquatic species and birdlife due to oil intoxication) and long term (such as decrease in fish and marine mammal species) (Marine Mammal Commission, 2011).

Maritime safety regulations such as the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea have been put in place to prevent oil leakages and to reduce accidents from happening. The first chapter of SOLAS deals with the construction, subdivision, stability and machinery and electrical installations. In 2010 "Goal-based standards" for oil tankers and bulk carriers were approved, obliging new ships to be designed and constructed for a specified design life and to “be safe and environmentally friendly, in intact and specified damage conditions, throughout their life” (SOLAS, 1974). These regulations have helped in improving maritime safety and accidents from happening; however due to the increasing size of vessels contemporary leakages and accidents have far more detrimental effects. When comparing the frequency of oils spills from tankers in the 1970s with those of our present decade, it is important to consider the continuous increase in capacity and size of ships and tankers. The increase of larger ships carrying much larger volumes of oil makes oil spills from these vessels potentially far more hazardous. In her study, Keisha (2005) demonstrates that over a 10 year period, out of 1,430,000 tons of oil spilt in oceans across the world, 990,000 tons (70%) were spilt in just 10 accidents (out of 395 recorded accidents). The PRESTIGE oil spill in 2002 also illustrates the proportional impact of bigger tankers on sea pollution. The PRESTIGE (63,000 tones) was responsible for exactly 94% of the total oil spills in that year across the world (Dailygreen, 2010)

Table 1: oil spills from 1970 to 2010 compared to seaborne oil trade

e) Climate Change

A final effect of shipping on the marine and global environment is the role of the maritime sector on global climate change. Climate change is widely acknowledged to be the consequence of massive industrial activities, characterized by an ever increasing release of emissions into the atmosphere and the vanishing of the world’s forest. It entails changes in weather patterns such as a rise in global temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, rising sea levels and melting of ice. Some of the changes in climate are naturally induced, but others are linked to human activity and are in many cases seen to be irreversible.

The maritime sector does not close its eyes for the effects of its greenhouse emissions and over the years various interventions have been designed to lower the emissions. An example of this is cold ironing, a technique where ships shut down their own power plants while at dock, and shift to shore side electricity. Other solutions for companies are increasing the number of operating vessels on routes to ensure that the vessels can go at lower speed producing lower emissions. Furthermore; ships can strive to reduce fuel consumption to cut emissions. All these solutions are environmentally friendly, but come at an economic cost for the vessel owners. As long as the solutions are not made economically friendlier (for example by subsidizing onshore electricity) the solutions might not be taken over by the majority of stakeholders (Bowman, 2008).

II – International legislation on Maritime Safety and the Prevention of Pollution from Ships: where is it lagging behind?

In the first section the pressures posed by the maritime sector on the marine environment were discussed. This section intends to investigate why these pressures are still so prevalent, when global governance structures have designed various conventions to protect the marine environment from the negative effects of shipping. This section will argue that the implementation of the discussed SOLAS and MARPOL regulations as established by the International Maritime Organization is not strictly enough executed causing risks for the environment, human health and the maritime transport sector.

Both the SOLAS and the MAPROL convention are crucial players in protecting the environment from the possible negative effects from shipping. The key purpose of the SOLAS convention is to specify standards for a ship’s structure, machinery and electrical installations for firefighting, live saving appliances, and radio communications. It also specifies standard for the carriage of cargo, carriage of dangerous goods, standard for nuclear ships, ISM, safety measures for high speed craft and other special measures to enhance maritime safety (SOLAS, 1974). Full implementation of these standards ensures improvements in the general safety of a ship, its passengers and its carriage. Simultaneously, when the safety of the ship is improved it is less likely to have an accident and pose a risk to the marine environment. IMO states that to prevent pollution safety is key and that governments and industries should focus more on reducing the number of accidents at sea that stem from human error. Estimates show that mistakes make op 80% of the total scope of marine pollution (IMO.org, 2012).

world’s tonnage (Marine Knowledge, 2011). Seeing that the majority of global tonnage is covered; it remains remarkable why the marine environment is still feeling so many pressures from the maritime sector.

When putting both conventions together; it seems that IMO developed a promising and global way to prevent and minimize marine pollution from happening. However; adopting conventions has shown not to be sufficient to protecting the environment, since most boils down to the actual implementation of them, which brings down the responsibility to the signatory states and stakeholders such as shipping companies, sea farers and individual boat owners.

It is often said that the responsibility for taking care of the environment is the responsibility for everyone; but this means at the same time that it is no one’s full responsibility. Preventing pollution from ships may vary from region to region, country to country, and even from port to port, and this makes it hard to control it from happening. Although countries may sign international conventions; enforcement often proofs to be ineffective. The situation is often worse in developing countries; where political corruption still takes place and where lacking financial resources disturb enforcement from happening. Also; many countries do not have the capacity to either prevent pollution from happening or to deal with existing pollution. A lack of global and national political will to truly defeat the majority of marine pollution is a serious threat. Furthermore, there is often inadequate data available on the scope and complexity of illegal pollution. Also, want maritime safety regulations are not well taken care off by ships from one country and an accident occurs in the waters of another country, the responsibility is not often strictly taken by the country whose ship caused the accident (INECE, 2009).

Conclusion

Although the maritime sector only contributes 12% to the total of marine pollution, it is still an important disturbance to the marine environment and the people whose livelihoods are dependent on the oceans. This essay discussed various pressures posed by the maritime sector on the marine environment; such as waste dumping, plastic debris, oil spillage and global climate change.

Global conventions have been put in place by international bodies such as the International Maritime Organization to mitigate the risks of shipping on the marine environment and to ensure that pollution is taken care of accordingly. IMO designed two major conventions; the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) and the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS). These global regulations have shown to be benchmarks in the protection of the marine environment, but it has also become clear that much is dependent on the individual implementation of the agreements by signatory states. Regulations mean nothing if they are not enforced. Since oceans are not strictly divided between countries in the same way as land is, it has proven to be difficult to inflict the international regulations.

Furthermore, financial benefits are often seen as more important than protecting the environment by companies and countries. For example, when it is too expensive to dispose waste in one country, then a company can almost certainly find another (developing) country that agrees to buy the waste for disposal for a fair amount. The costs of these activities on the marine environment as well as on the health and livelihoods of the local communities are often neglected. Furthermore, although wealthy countries have a far bigger share in the global maritime trading, it is more often the poor countries that suffer the most from marine pollution, because of insufficient knowledge, capacity funding and weak governments to protect the oceans. Therefore, global enforcement could help in holding governments accountable for the damage caused in other countries.

References

Adolf K.Y. Ng & Gordon Wilmsmeier, 2012, the Geography of Maritime Transportation: Space as a Perspective in Maritime Transport Research, Maritime Policy & Management, Volume 39, Issue 2.

Bijal, P.T., 2002. Invasive species “Stowaways” May Lose Ride on Ships. National Geographic Today, [Online]. Available at:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/01/0109_020109TVballastwater.html [Downloaded 5 May 2012].

Bowman, R.J. 2008, Ships and Ports Explore Many Ways to Go Green, Global Logistics & Supply Chain Strategies | September 10, 2008

Cangelosi, A. 2002-2003. "Blocking invasive aquatic species." Marine Pollution Bulletin 44: 32-38. 3. Issues in Science and Technology 19(2): 69-74. Available at: http://www.issues.org/19.2/cangelosi.htm [Downloaded 5 May 2012].

Carbone, N. 2012, Massive Fishing Dock Washes Ashore in Oregon, 15 Months After Japanese Tsunami, Time Magzazine , [online] Available at:

http://newsfeed.time.com/2012/06/07/massive-fishing-dock-washes-ashore-in-oregon-15- months-after-japanese-tsunami/#ixzz1xqIOURe. [Downloaded 5 May 2012].

Copeland, C. 2008. Cruise Ship Pollution: Background, Laws and Regulations, and Key Issues Congressional Research Service. [online] Available at:

http://cep.unep.org/publications-and-resources/databases/document-

database/other/cruise-ship-pollution-background-laws-and-regulations-and-key-issues.pdf.[Downloaded 12 May 2012]. [Downloaded 12 June 2012].

Derraik,J.G..B., 2002. The pollution of the marine environment by plastics debris: a review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 44, 842-852, [online]. Available at:

http://5gyres.org/media/Derraik_2002_Plastic_pollution.pdf [Downloaded 8 May 2012].

Greenpeace International, 2006, Plastic Debris in the World’s Oceans, Amsterdam, [online]. Available at

http://www.unep.org/regionalseas/marinelitter/publications/docs/plastic_ocean_report.pdf [Downloaded 8 June 2012].

International Chamber of Shipping & International Shipping Federation, 2012, [online] Available at: http://www.marisec.org/shippingfacts/environmental/small-contribution-to- overall-marine-pollution.php, [Downloaded 13 May 2012].

International Maritime Organization, (2011), IMO and the environment, London. [online] Available at

International Maritime Organization, (2012), www.imo.org.

International Network for Environmental Compliance and Enforcement Seaport Environmental Security Network, 2009, The International Hazardous Waste Trade Through Seaports, [online]. Available at:

http://www.inece.org/seaport/SeaportWorkingPaper_24November.pdf. [Downloaded 12 May 2012].

Keisha, H., 2005. Trends in Oil Spills from Tankers Ships 1995-2005. In: ITOPF (International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation), 28th arctic and marine oil spill program: Technical seminar. 7-9 June 2005. Calgary: Canada

MacPhee, B., 2006. Alien Flotillas: The Expansion of Invasive Species through ship ballast water. Earth Trends, [online]. Available at:

<http://whub27.webhostinghub.com/~noport5/mambo/images/stories/PDFfiles/alien%20f lotillas-invasives.pdf> [Downloaded 5 May 2012].

Marine Knowledge, 2011, Marpol,[online]. Available at: http://www.marine- knowledge.com/marine-law/marpol.html, [Downloaded 5 May 2012].

Marine Mammal Commission, 2011, Assessing the Long-term Effects of the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill on Marine Mammals in the Gulf of Mexico: A Statement of Research Needs, [online]. Available at:

http://mmc.gov/reports/workshop/pdf/longterm_effects_bp_oilspil.pdf [Downloaded 5 May 2012].

OCEANA, n.d. Protect our oceans: Stop cruise Ship Pollution. [online] Available at: http://oceana.org/sites/default/files/o/uploads/cruiseshipwaste_uslawsandregulations.pdf [Downloaded 8 May 2012].

Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2010, Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the House of Commons, Chapter 1 Oil Spills from Ships, Available at: http://www.environmental-

auditing.org/Portals/0/AuditFiles/Canada_f_eng_Spills-from-Oil-Ships.pdf, [Downloaded 5 May 2012].

SOLAS, 1974, International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) 1974, [online] Available at:

http://www.imo.org/about/conventions/listofconventions/pages/international-convention- for-the-safety-of-life-at-sea-%28solas%29,-1974.aspx, [Downloaded 1 June 2012].

The Daily Green, 2010, 10 of the World's Worst Energy Disasters: The Prestige Oil Spill: it was one of the worst oil spills in history, and it didn't have to happen. [online]

Available at: http://www.thedailygreen.com/environmental-news/latest/prestige-oil-spill [Downloaded 6 June 2012].

The Global Environment Facility (GEF), 2011, Marine Debris as a Global

Environmental Problem Introducing a solutions based framework focused on plastic. [online] Available at:

www.thegef.org/gef/.../STAP%20MarineDebris%20-%20website.pdf. [Downloaded 1 June 2012].

Transfigura, 2012, Probo Koala Updates, [online] Available at:

http://www.trafigura.com/our_news/probo_koala_updates.aspx [Downloaded 1 June 2012].

World shipping council, 2012. Invasive Species. [online] Available at:

http://www.worldshipping.org/industry-issues/environment/invasive-species [Accessed 9 May 2012].

United Nations Economic and Social Council, Economic Commission for Africa, 2009, Sixth Session of the Committee on Food Security and Sustainable Development (CFSSD-6)/Regional Implementation Meeting (RIM) for CSD-18.

United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2006. Cruise Ship Wasterwater Discharges. [Online] Available at

http://water.epa.gov/polwaste/vwd/upload/2006_10_9_oceans_cruise_ships_wastewaterf actsheet.pdf [Accessed 8 May 2012].

United States Environmental Protection Agency, (2012), Vessel Water Discharge, Available at http://water.epa.gov/polwaste/vwd/wastewaterfactsheet.cfm,[Accessed 8 May 2012].