Art. # 947, 9 pages, http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za

Mothers’ reflections on the role of the educational psychologist in supporting their

children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

K Mohangi

Department of Psychology of Education, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa mohank@unisa.ac.za

K Archer

Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, South Africa

The characteristically disruptive conduct exhibited both at school and home by children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) appears to be particularly emotionally difficult for the children’s mothers, who often turn to educational professionals for guidance. With a view to improving best practice in assistance to mothers and to promoting the tenets of inclusive education policy, the authors investigated the ways in which mothers experienced the support provided by educational psychologists. A qualitative interpretivist approach was adopted, with five purposefully selected mothers, whose children had previously been diagnosed with ADHD. Data was gathered from a focus group discussion and an individual interview. It emerged that mothers experienced parenting their children with ADHD as stressful, requiring continual re-assurance and emotional support from educational psychologists. Having need of counselling for their families and academic help for their children, these mothers expected that educational psychologists should collaborate with educators and other role players, so as to enhance overall support to their children as learners. The findings pointed to the need for an effective inclusive school environment that forefront the role of educational psychologists in sharing knowledge and working collaboratively across the education system in South Africa.

Keywords: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; collaboration; educational psychologist; inclusive education; support

Introduction

South Africa’s membership as part of the Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) economic coalition serves as a reliable indicator of its sound positioning as a leading emerging economy in Africa. Moreover, as noted by the Global Competitiveness Report (2012-2013) (Schwab, 2012), the country’s economy has remained stable in the face of global economic uncertainty. While such stability usually heralds improved resources for any country, the full benefits of dedicated resourcing have not been evident in South Africa’s public education sector, which should serve as a crucially important driving force for further socio-economic development. On the contrary, attempts at macro- and micro-levels to reconfigure the country’s educational landscape have continually been hamstrung by significant socio-economic disparities that have remained as residuals of past political inequalities (Dieltiens & Meny-Gibert, 2012). The diminution of resource gaps within urban schools may have given rise to an illusion of change for the better, but this is belied by the fracturing of education in large parts of the country through under-resourcing of teaching and learning environments (Sedibe, 2011). The critical role of adequate resources implies that any insufficiencies in this respect will inevitably exert an adverse effect on improving educational outcomes. Thus, the need for educational planning research into the role of supportive resourcing in educational reform within the South African education system appears mandatory.

Research into inclusive education specifically, may well be the focal point in the creation of a socially just society, in which all individuals feel that they have been able to fulfil their potential and attain a way of life that benefits both themselves and the wider society (Polat, 2011). In South Africa, the need for such research is underscored by social justice factors – particularly the development of quality education for all – and is found most of all in the requirement for informed decision-making by policy makers and the provision of solid foundations for best-practice approaches.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

ADHD, a chronic neurological condition, is one of the most ubiquitous disorders among children and adolescents worldwide, affecting approximately 5% of the school-aged population (Polanczyk, De Lima, Horta, Biederman & Rohde, 2007), with its prevalence being estimated at between 8 and 10% in South Africa (Louw, Oswald & Perold, 2009; Perold, Louw & Kleynhans, 2010).

The link between ADHD and learning difficulties is well substantiated (Barkley, Murphy & Fischer, 2008; Harrison & Sofronoff, 2002; Wicks-Nelson & Israel, 2009). As one of the key challenges that create barriers to learning, ADHD is characterised by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention and/or impulsivity-hyper-activity (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2013). Between 30 and 70% of diagnosed children and adolescents continue to experience difficulties into adulthood (Mahomedy, Van der Westhuizen, Van der Linde & Coetsee, 2007).

Behaviours associated with ADHD result in significant challenges in school settings, with learners exhibiting academic underachievement, disruptive conduct, and poor peer relationships (Barkley, 2006; DuPaul, 2007). Attendant condi-tions like anxiety and depression can exacerbate such behaviours (Barkley, 2012, 2013). A less direct consequence of ADHD includes difficulties in processing social cues (Seabi & Economou, 2012). Such problems, in association with the more commonly pronounced characteristic of impuls-ivity, namely the inability to inhibit inappropriate behaviour (Van der Westhuizen, 2010; Wicks-Nelson & Israel, 2009), can make social integration problematic. Often presenting as inhibited, with-drawn or distracted (considering that impulsivity is not to be equated with authentic extroversion), some children and adolescents with ADHD may be ignored by their peers (Wicks-Nelson & Israel, 2009), whereas others may experience humiliation and intense levels of stress, as the educational environment confronts them with various challeng-es. It is not uncommon for learners with ADHD to develop low academic self-concepts, owing to frequent experiences of emotional, scholastic, and social failures early on in their school careers (Seabi & Economou, 2012).

The nature of ADHD is such that it places increased demands on family functioning, and disrupts the processes of parenting and caregiving, while disempowering parents so that they feel incompetent, disillusioned, and distressed about their parenting skills (Finzi-Dottan, Triwitz & Gol-ubchik, 2011; Swensen, Birnbaum, Secnik, Maryn-chenko, Greenberg & Claxton, 2003; Theule, Wie-ner, Rogers & Marton, 2011; Wicks-Nelson & Israel, 2009). Affected families experience the start of difficulties in family functioning and relation-ships when the child is young. These difficulties

seem to intensify during the adolescent years (Cunningham, 2007; Johnston & Mash, 2001).

Although both parents are usually at risk for a breakdown in their relationship with their child with ADHD (Kazdin & Whitley, 2003), it seems that mother-child relations are more strained than are father-child interactions (McLaughlin & Harrison, 2006). This may affect the capability of the mother to use positive parenting practices to produce cooperative conduct in their child (Cunningham, 2007; Kazdin & Whitley, 2003). Recent family research recommends that nurturing roles should be shared, which has the advantage of relieving the pressure on the mother and emphasising the need for a more present fatherly role (in traditional family compositions) (Prithi-virajh & Edwards, 2011).

Difficulties with parenting a child with ADHD are often a reason for parents to seek professional help from an educational psychologist. Although some research (Prithivirajh & Edwards, 2011) describes the distress that parents experience in parenting children with ADHD, there seems to be a gap in understanding of the ways in which the educational psychologist in a South African context can support parents in particular. Despite limited South African research on this topic, it has been shown that social support is a valuable resource in reducing the stress experienced by families of children with ADHD (Finzi-Dottan et al., 2011). Psycho-education and parent training have been found to be acceptable means of supporting parents of children with ADHD (Deault, 2009; Finzi-Dottan et al., 2011; Van de Wiel, Mattys, Cohen-Kettenis & Van Engeland, 2002). Such support may require assisting parents with the daily tasks involved in managing their child, such as im-plementing routine, effective discipline practices, and homework intervention strategies. Support could also include establishing mothers’ sense of confidence in their parenting abilities and im-plementing coping strategies through, for example, support groups with other mothers experiencing similar difficulties.

Educational Psychology Support

Much of the research into ADHD management has focused on the child and improving the child’s overall functioning (Gerdes, Haack & Schneider, 2012), with recent indications being that a multi-modal treatment approach has the best outcomes (Montoya, Colom & Ferrin, 2011). This may involve medication, psychological and psycho-social therapies (Montoya et al., 2011), and stress-management training for parents (Prithivirajh & Edwards, 2011).

psycho-education implemented across home and school settings are equally effective (Gerdes et al., 2012). DuPaul, Eckert and Vilardo (2012) discovered that a variety of school-based interventions were associated with moderate to large improvements in academic and behavioural functioning of learners with ADHD, including psycho-education, development of skills, and client empowerment (Montoya et al., 2011). Indications are, furthermore, that parents with more knowledge about ADHD report greater confidence in their parenting abilities, and better control over their children’s behaviour (Cunningham, 2007). Treatment strategies consequently need to extend beyond symptom reduction, in order to exert a positive effect on critical areas of functioning such as academic performance (Evans, DuPaul, Mautone, Owens & Power, 2012). Interventions at the individual, home, and school levels also appear to be more successful if they are introduced early (Evans et al., 2012).

Educational psychologists in South Africa are mainly responsible for assessing and supporting children with special educational needs (Farrell, 2004), and the scope of their duties is formally defined in the Health Professions Act (No. 54 of 1974) as inter alia “assessing, diagnosing, and intervening in order to optimise human functioning in the learning and development”, and “applying psychological interventions to enhance, promote and facilitate optimal learning and development” (Department of Health, 2011:8). According to Geldenhuys and Wevers (2013), South African schools lack the capacity for the early identification of learners who experience barriers to learning, proper assessment of learner’s strengths and weak-nesses and limited collaboration and cooperation between microsystems. In this regard, Bojuwoye, Moletsane, Stofile, Moolla and Sylvester (2014) state that the provision of support for effective learning in schools ought to extend beyond the institution, and that the aim of providing support services is to serve as a capacity building strategy in addressing learning difficulties. South Africa is limited in empirical knowledge on the potentially supportive role of the educational psychology field within inclusive settings. This deficiency is es-pecially evident in areas regarding the effects of collaboration with schools, allied healthcare prac-titioners, and parents to maximise the success of the child with ADHD (Finzi-Dottan et al., 2011; Seabi & Economou, 2012). It is therefore par-ticularly essential in an emerging economy such as South Africa’s that the field of educational psychology expand its focus from a unitary medical perspective to a constructivist, resource-based, and research-driven approach to assessment and inter-vention.

Goal of the Study and Research Questions

The primary goal of the study was to explore the ways in which mothers of children with ADHD experienced educational psychology support in order to improve best practice in assistance to such mothers, and to promote the tenets of inclusive education policy by contributing to the corpus of research used by policy makers. The following research questions guided this enquiry: 1) How do mothers of children with ADHD experience support from an educational psychologist? 2) What are mothers’ understandings of the role of the educational psychologist in supporting their chil-dren with ADHD?

Framing the Study

Guided by a systems theory perspective and an inclusive education framework, the authors’ point of departure in this study was that collaboration across educational support systems influences learners’ educational outcomes positively. Bronfen-brenner refers to proximal processes in the context of mediating environments such as the school, peer group and the family, in which the learner actively engages (Swart & Pettipher, 2011). Since effective functioning within learners’ educational micro-systems (school level) affects their achievement, long-term educational outcomes, and psychological well-being (Reschly & Christenson, 2012), edu-cational psychologists have a pivotal function, to fulfil in a collaborative systems approach by con-stituting a central linkage in the web of significant players in the subsystems of the inclusive school community, the family, and the child with ADHD.

Furthermore, in South Africa the implement-ation of inclusive educimplement-ation policies is largely focused upon a socio-ecological and collaborative approach to learning support. Contextual influenc-ing factors are considered important in how support is offered and received. As inclusive education practices are supported by the bio-ecological model of Bronfenbrenner, there abound a multitude of influences, interactions, and interrelationships between the learner and other systems (Swart & Pettipher, 2011). Thus, utilising a systemic app-roach to learning support within inclusive education requires that all the influences, inter-actions, and interrelationships are explored by role players in the relevant systems working together in collaborative partnerships (Engelbrecht, 2007; Swart & Pettipher, 2011).

& Harvey, 2010). Where collaboration in the school community is the norm, parents and learners are likely to feel comfortable (Gimpel Peacock & Collett, 2009) and educational psychologists work-ing within an inclusive school environment have further opportunities to foster such collaborative relationships with the intention of optimising the learning and development of learners with ADHD (Engelbrecht & Green, 2001).

Research Methodology

A qualitative approach within an interpretivist paradigm allowed for a phenomenological per-spective (Nieuwenhuis, 2007a) in terms of which the authors relied on participants’ views, con-centrating on their meaning and interpretations (Creswell, 2007; Henning, Van Rensburg & Smit, 2004; Nieuwenhuis, 2007a). Within the multiple case study design, data was generated by means of a focus group discussion including all participants, and a one-on-one interview with a purposively selected participant (Nieuwenhuis, 2007b). Pur-posive and convenience sampling procedures were applied for selecting the five participants for the focus group and individual interviews (Creswell, 2007; Henning et al., 2004), since this type of sampling lends itself to information-rich cases, highlighting the questions under study (Patton, 2002). Participants were selected as mothers of children attending either an independent

main-stream school or an independent special-needs school in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Further basis for selection included having a child or children diagnosed with ADHD by an educational psychologist, and having had to consult with an educational psychologist previously. The authors were flexible in allowing one mother with adult children to participate in this study, as it was deemed that she possessed substantial experience and information that could contribute to the study.

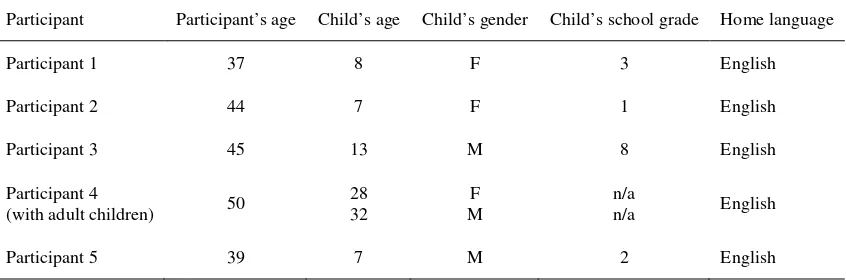

The limited scope of this study did not allow for the inclusion of fathers. Ethical considerations, such as participants’ right to anonymity, confident-iality and voluntary participation, were respected. Furthermore, participants were provided with an opportunity to enquire about the research processes prior to signing the letter of informed consent. The appropriate ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Pretoria, and all other required guidelines were adhered to. Open-ended questions allowed mothers to reflect on their experiences. Interviews were recorded and member-checking for quality assurance was conducted. In order to establish the trustworthiness of the study, the au-thors ensured that the results were dependable, credible, confirmable, transferable and authentic. A systematic approach to content analysis was em-ployed to identify and summarise message content (Creswell, 2007). The relevant details of partici-pants and their children are reflected in Table 1.

Table 1 Participants’ details

Participant Participant’s age Child’s age Child’s gender Child’s school grade Home language

Participant 1 37 8 F 3 English

Participant 2 44 7 F 1 English

Participant 3 45 13 M 8 English

Participant 4

(with adult children) 50

28 32

F M

n/a

n/a English

Participant 5 39 7 M 2 English

Findings

Thematic data analysis of mothers’ perceptions (referred to as “reflections”) on the role of educational psychologists in supporting their chil-dren with ADHD revealed their need for in-depth explanations, additional emotional support, and collaborative professional management of their children’s difficulties. The results are presented in terms of emergent themes, with supporting quo-tations from interview transcriptions.

Reflections on the Role of an Educational Psychologist as a Source of Support

The mothers generally appeared to experience parenting their children with ADHD as stressful,

reporting high levels of frustration and increased tension at home. All five participants agreed that substantial and different levels of support from an educational psychologist might alleviate their stress, but their insight into the overall tasks of the educational psychologist and expected forms of support, varied between being unsure, and being fairly well-informed.

It is quite a broad role, [including] testing, play therapy, diagnosis of different learning areas and learning problems and [the] ADHD aspect. A lot of parents maybe feel that an educational psychologist is only used for identifying problems, especially ADHD, and I think [this] is something [the] school need[s] to work on. […] they could offer so much more to the staff and parents; but I don’t think that role is fulfilled at the moment (Participant 5, interview).

Another participant, in commenting on the educational psychologist’s scope of practice, thought it unethical for the psychologist to simply make a diagnosis of ADHD without following up with the parents or making further recomm-endations to them:

As an educational psychologist, to just diagnose and then to leave you alone… I think they need to recommend and suggest, and talk and say ‘okay, let's have a session, and this is what I think, what the options are’ [sic]. Then you make a decision, you [can decide whether you] want that support. She should be saying, ‘this is what I can offer; this is the kind of thing that we do, that are within our scope’ (Participant 2, focus group).

This participant was of the opinion that it ought to be parents who decided whether they required ongoing assistance, thereby sharing the decision-making responsibilities with the educational psychologist. She also considered it necessary for educational psychologists to be clear about the respective roles and responsibilities of parents and children. Participant four expressed her need for in-depth explanations as she was: going in there [sic]

as a parent for the first time, you don't know this

(Participant 4, focus group).

It became clear that all the participants had some form of expectation of emotional support for the family, from the educational psychologist:

‘Maybe some follow-up phone calls or appoint-ments to find out how it is going with the family

[can be recommended], [ascertaining] where we

need help and what challenges we are facing, […] I

think I would really find that useful’ (Participant 5, interview). With varying degrees of understanding and expectation of the role of the educational psychologist being apparent among the mothers, it was also evident that they looked to the educational psychologist for clarification of the roles and res-ponsibilities of all concerned at the outset of the consultative process.

Reflections on Educational Psychology Processes All mothers in this study had consulted with an educational psychologist for an in-depth edu-cational psychology assessment for their children. Usually, an educational psychology assessment process consists of an initial intake interview with the parents, followed by a battery of cognitive, scholastic, and emotional assessments tailored to the child’s needs and the reasons for the assess-ment. The parents are then invited to a feedback

session, at which the educational psychologist re-ports on the findings of the assessment.

Regarding participants’ perceptions of the assessment and therapeutic processes, they found these processes to be a positive experience, and considered the support provided during the assess-ment process to be adequate. The assessassess-ment findings generally guide the recommendations made to the parents. A participant related that, ‘[her and her husband] found the support during the

whole assessment process very good and [agreed

with] all the information [in] the report […]’ (Participant 5, interview).

Another participant also expressed her positive experience with the assessment and feedback processes:

The assessment for me was incredibly useful. She [educational psychologist] was amazing. The assessment was good; she gave the report back at her office, lots of things to recommend (Participant 3, focus group).

In this study, it was found that only one of the participants had been given recommendations regarding recourse to additional therapeutic pro-cesses (e.g. neurological tests or occupational therapy) for her child after the diagnosis of ADHD had been made. The other mothers felt that edu-cational psychologists had had little to offer, aside from the initial diagnosis of ADHD, accompanied by a recommendation to start with a medication regimen.

Some participants indicated that their children were engaged in therapy with the educational psychologist after the diagnosis of ADHD had been made, and one mother even reported that her child loved therapy, especially since the educational psychologist seemed to be assisting in elevating the child’s self-esteem. Supportive collaboration among professionals in the school system may in-clude the educators, the institutional-level and district-based support teams, as well as various healthcare practitioners, such as occupational ther-apists, speech and language therther-apists, optome-trists, and neurologists. Some mothers felt that such a collaborative relationship and sharing of know-ledge among professionals could improve under-standing of their children’s difficulties, and cause the children to feel more supported during inter-ventions that would reflect a greater measure of inclusivity.

Reflections on Educational Psychology Support for the Child and for the Parent

therapeutic support - if provided - could have been of a better quality. For example, three participants noted that little else was offered beyond a bare diagnosis.

See [sic], she had no recommendations for L, other than: ‘okay [sic], well he's ADD’ and ‘get on with it’ [sic]. ‘Yeah and get your child medicated’ [sic] (Participant 2, focus group).

My experience has been a diagnostic one. She's diagnosed him and that was it [sic](Participant 4, focus group).

‘This is the diagnosis’. There wasn’t much follow-up at all (Participant 3, focus group).

Aside from insufficient and inadequate support for some children, participants also felt that the support that they themselves received was limited, with at least four of them feeling that they had been left to their own devices. The types of support that they felt they needed from educational psychologists could be described as follows: a) providing reassurance and emotional support in terms of allaying their fears, in other words, they wanted to hear that what they were feeling and experiencing was normal: sometimes I feel so alone and would like to chat to others about how they handle it all, it can all be so hard. I think that would also be

helpful to hear […] from the other parents as well

(Participant 5, interview); b) providing information and guidance about what to expect as parents of children with ADHD: I would appreciate maybe right from the beginning, when the diagnosis was made and the report was given back, maybe some assistance with regard to some websites to look at, information booklets or books we could read as a couple (Participant 5, interview); c) facilitating support groups for mothers of children with ADHD in order for them to benefit from sharing ex-perience, thus gaining new knowledge and ob-taining additional emotional support as is clear in the following extract: I think it would just make a huge difference, even just support in that form

[parent support group] would be good too. I just feel if they could have a support group for the parents that you use to say look this is what my child's doing, yes, mine’s doing the same. This is what I would you know, this is how you could possibly deal with it, don't worry about it

(Participant 4, focus group); d) providing personal follow-up and offering assistance where possible:

Even just say like in say three months’ time I just want to touch base again you know, what's

happening just to see where you are (Participant 2,

focus group); and e) fulfilling an intermediary or liaison function at school level in enlightening educators who were generally lacking in knowledge and understanding of ADHD.

Reflections on Knowledge Sharing and Interaction between Professionals

If intraschool-level liaison could be considered as being at micro level, four out of the five mothers

gave indication that they were aware of advantages to be derived from liaison at what could be called macro level. They felt that it would benefit the educational psychologist to work in collaboration with other professionals within all systems of the school community, for example the educators, the institutional-level and district-based support teams, as well as the various health care practitioners such as occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, and even neurologists to provide support for parents and learners in dealing with ADHD. During the focus group, participant three indicated that:

it was a pity that schools like our school, does not have the support, to be able to have somebody who can really interact with the teachers because I feel like as much as our teachers are supporting, they don't really get it.

Another participant noticed that,

there’s not enough interaction between them, I would have liked the educational psychologist maybe to come and meet the teacher (Participant 2, focus group).

Discussion

Given that ADHD places strain on family fun-ctioning (Cunningham, 2007), the participants in this study reported high levels of stress associated with parenting their children with ADHD. Hence, participants expressed the need for the educational psychologist to adopt a more supportive role for them as a family, since the resultant reduction of stress levels would in their view lead to a better ability to cope. This finding is consistent with the view of Finzi-Dottan et al. (2011) that support is a valuable resource in reducing stress experienced by families of children with ADHD.

In this study, participants also indicated their need for the educational psychologist to establish or facilitate support groups for individual work with families. Parents in particular needed to ac-quire knowledge about ADHD and, as part of the educational psychologist’s scope of responsibility, it is therefore vital that psycho-education on the disorder should be provided to them. Montoya et al. (2011) claim that knowledge about ADHD, its treatment, and consequential stressors need to be discussed with parents.

The participants in the current study indicated that the educational psychologist should be interacting with other professionals in order to support them and their children better. Addition-ally, participants voiced their frustration at educators’ lack of understanding and knowledge of ADHD. This finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted in the Western Cape Province of South Africa on primary school educators’ knowledge and misconceptions of ADHD (Perold et al., 2010). It was reported that educators had a substantial lack of knowledge, in particular, when it came to key areas of ADHD.

According to Swart and Pettipher (2000), as well as Bothma, Gravett and Swart (2000), South African educators have not been trained to cope with the increasing diversity of learners entering mainstream classrooms, and such learners con-sequently lack support. Thus, to fill the gap, educational psychologists could provide training for educators who may feel that they lack knowledge of ADHD and, in particular, could guide educators in communicating effectively with parents (Rogers, Weiner, Marton & Tannock, 2009). The literature suggests that the role of the educational psychologist should extend to all learners experiencing barriers to learning, their parents, the school-based support team, medical practitioners, and the wider community in order to create an inclusive school environment (Bradley, King-Sears & Tessier-Switlick, 1997). If the interconnectedness of the various components of the educational-cum-community system is viewed through an ecosystemic lens, it becomes apparent that the school could play a significant role in lessening the emotional impact of parenting children with ADHD.

The needs of the emergent South African economy dictate that research-driven policy decisions and best-practice approaches in the field of inclusive education ought to be paramount in order to sustain the momentum of reform. This paper established the need to listen to the voices of key participants in the inclusive process, as evidence for the need to reflect on, revise, and rethink the manner in which educational psychologists practice their profession.

Limitations of this Study

The primary limitation was the small sample size, where, because of the restricted scope of the study in which only five participants were interviewed. Therefore, the authors needed to be cautious in making generalisations and oversimplifying part-icipants’ experiences.

Conclusion

The authors reported on mothers’ perceptions of educational psychology support and the challenges facing mothers while parenting their children with

ADHD. Greater levels of support for these families can be achieved if educational psychologists pro-vide assistance through their individual involve-ment with families as well as with parent support groups. This could subsequently nurture parent interactions and constructive parent involvement in the child's learning. They could also advise parents on the benefits of increased involvement in their child’s education and school life. Moreover, the educational psychologist could play a pivotal role in breaking down the barriers between the school, the parents, and the other professionals involved in the child’s life (Rogers et al., 2009). The findings suggest the need for collaborative relationships to be forged between the different learning communities, such that they come to share knowledge and to focus on support. The role of the educational psychologist in forging these collaborative associations is clear. Furthermore, not only do educational psychologists as individuals have a pivotal role to play in facilitating the suc-cessful development of inclusive education prac-tices in South Africa, it is also essential that the entire South African field of educational psych-ology align itself with the international leaning towards family-centred and transdisciplinary inter-vention. The findings of this study reinforce the need for supportive resourcing in educational re-form within the South African education system.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge that the intellectual property of this study rests with the University of Pretoria.

References

American Psychiatric Association 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. Barkley RA 2006. Attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder: a handbook for diagnosis and treatment (3rd ed).New York: The Guildford Press.

Barkley RA 2012. Effectiveness of restricted elimination diets for management of ADHD: concerns about the 2011 INCA Study. The ADHD Report, 20(5):1-5, 11-12.

Barkley RA 2013. Distinguishing sluggish cognitive tempo from ADHD in children and adolescents: executive functioning, impairment and comorbidity. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(2):161-173.

Barkley RA, Murphy KR & Fischer M 2008. ADHD in adults: what the science says. New York: Guildford Press.

Bothma M, Gravett S & Swart E 2000. The attitudes of primary school teachers towards inclusive education. South African Journal of Education, 20(3):200-204.

Bradley DF, King-Sears ME & Tessier-Switlick DM 1997. Teaching students in inclusive settings: From theory to practice. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Creswell JW 2007. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed). New Jersey: Pearson, Merrill Prentice Hall.

Cunningham CE 2007. Family-centered approach to planning and measuring the outcome of interventions for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7(Supplement 1):60-72.

Deault LC 2010. A systematic review of parenting in relation to the development of comorbidities and functional impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41(2):168-192.

Decaires-Wagner A & Picton H (eds.) 2009. Teaching and ADHD in the Southern African classrooms. Northlands: Macmillan South Africa.

Department of Education, South Africa 2001. Education White Paper 6: Special needs education: building an inclusive education and training system. Pretoria: Department of Education. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileti cket=gVFccZLi/tI=. Accessed 7 December 2014. Department of Health, South Africa 2011. Health

Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974): Regulations defining the scope of the profession of psychology, No. R. 704. Government Gazette, 34581. Available at

http://www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/editor/UserFiles/d ownloads/psych/sept_promulgated_scope_of_pract ice.pdf. Accessed 7 December 2014.

Dieltiens V & Meny-Gibert S 2012. In class? Poverty, social exclusion and school access in South Africa. Journal of Education, 55:127-144.

DuPaul GJ 2007. School-based interventions for students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: current status and future directions. School Psychology Review, 36(2):183-194.

DuPaul GJ, Eckert TL & Vilardo B 2012. The effects of school-based interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis 1996-2010. School Psychology Review, 41(4):387-412. Engelbrecht P 2007.Creating collaborative partnerships

in inclusive schools. In P Engelbrecht and L Green (eds). Responding to the challenges of inclusive education in Southern Africa. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

Engelbrecht P & Green L (eds.) 2001. Promoting learner development: preventing and working with barriers to learning. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Epstein JL & Sanders MG 2006. Prospects for change: preparing educators for school, family, and community partnerships. Peabody Journal of Education, 81(2):81-120.

Evans SW, DuPaul GJ, Mautone JA, Owens JS & Power TJ 2012. An evidence-based model of care for youth with ADHD. Paper presented at the annual

conference for the National Association of School Psychologists, Philadelphia, PA.

Farrell P 2004. School psychologists making inclusion a reality for all. School Psychology International, 25(1):5-19.

Finzi-Dottan R, Triwitz RS & Golubchik P 2011. Predictors of stress-related growth in parents of children with ADHD. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(2):510-519.

Geldenhuys JL &Wevers NEJ 2013. Ecological aspects influencing the implementation of inclusive education in mainstream primary schools in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 33(3):Art. #688, 18 pages,

http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za

Gerdes AC, Haack LM & Schneider BW 2012. Parental functioning in families of children with ADHD: evidence for behavioral parent training and importance of clinically meaningful change. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16:147-156. Gimpel Peacock G & Collett BR 2009. Collaborative

home/school interventions evidence-based solutions for emotional, behavioral, and academic problems. New York: Guilford Press.

Harrison C & Sofronoff K 2002. ADHD and parental psychological distress: role of demographics, child behavioral characteristics, and parental cognitions. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41:703-711.

Henning E, Van RensburgW & Smit B 2004. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Johnston C & Mash EJ 2001. Families of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review and recommendations for future research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4(3):183-207.

Kazdin AE & Whitley MK 2003. Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3):504-515.

Loreman T, Deppeler J & Harvey D 2010. Inclusive education: supporting diversity in the classroom (2nd ed). London and New York: Routledge. Louw C, Oswald M & Perold M 2009. General

practitioners’ familiarity, attitudes and practices with regard to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults. South African Family Practice, 51(2):152-157.

Mahomedy Z, Van der Westhuizen D, Van der Linde MJ & Coetsee J 2007. Persistence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adulthood: a study conducted on parents of children diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 10(1):93-98. McLaughlin D & Harrison C 2006. Parenting practices of

mothers of children with ADHD: the role of maternal and child factors. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 11:82-88.

Montoya A, Colom F & Ferrin M 2011. Is psychoeducation for parents and teachers of children and adolescents with ADHD efficacious? A systematic literature review. European Psychiatry, 26:166-175.

necessity of providing support to all learners. In N Nel, M Nel & A Hugo (eds). Learner support in a diverse classroom: A guide for foundation. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Nieuwenhuis J 2007a. Analysing qualitative data. In K Maree (ed). First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Nieuwenhuis J 2007b. Qualitative research designs and data gathering techniques. In K Maree (ed). First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Patton MQ 2002. Qualitative research and evaluations methods (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Perold M, Louw C & Kleynhans S 2010. Primary school teachers’ knowledge and misperceptions of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). South African Journal of Education, 30:457-473. Polanczyk G, De Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J &

Rohde LA 2007. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6):942-948.

Polat F 2011. Inclusion in education: A step towards social justice. International Journal of Education Development, 31(1):50-58.

Prithivirajh Y & Edwards SD 2011. An evaluation of a stress management intervention for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Human and Social Science, 3(1):32-37.

Reschly AL & Christenson SL 2012. Moving from “context matters” to engaged partnerships with families. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 22(1-2):62-78.

Rogers MA, Weiner J, Marton I & Tannock R 2009. Parental involvement in children's learning: comparing parents of children with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of School Psychology, 47(3):167-185. Schwab K 2012. The Global Competitiveness Report

2012-2013. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum. Available at

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalComp etitivenessReport_2012-13.pdf. Accessed 12 November 2013.

Seabi J & Economou NA 2012. Understanding the

distracted and the disinhibited: experiences of adolescents diagnosed with ADHD within the South African context. In JM Norvilit (ed). Contemporary trends in ADHD research. Croatia & China: InTech. Available at

http://www.intechopen.com/books/contemporary- trends-in-adhd-research/understanding-the- distracted-and-the-disinhibited-experiences-of-adolescents-diagnosed-with-adhd-wit. Accessed 7 December 2014.

Sedibe M 2011. Inequality of access to resources in previously disadvantaged South African high schools. Journal of Social Sciences, 28(2):129-135. Swart E & Pettipher R 2000. Barriers teachers

experiences in implementing inclusive education. International Journal of Special Education, 15(2):75-80.

Swart E & Pettipher R 2011.A framework for

understanding inclusion. In E Landsberg, D Krüger & E Swart (eds). Addressing barriers to learning: a South African perspective (2nded). Pretoria: Van

Schaik.

Swensen AR, Birnbaum HG, Secnik K, Marynchenko M, Greenberg P & Claxton A 2003. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: increased costs for parents and their families. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(12):1415-1423.

Theule J, Wiener J, Rogers M & Marton I 2011. Predicting parenting stress in families of children with ADHD: parent and contextual factors. Journal of Child Family Studies, 20(5):640-647.

Van de Wiel N, Mattys W, Cohen-Kettenis PC & Van Engeland H 2002. Effective treatments of school-aged conduct disordered children:

recommendations for changing clinical and research practices. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 11(2):79-84.

Van der Westhuizen A 2010. Evidence-based pharmacy practice (EBPP): attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). SA Pharmaceutical Journal, 77(8):10-14, 16, 18-20.