Labor Market Effects of

September 11

thon Arab

and Muslim Residents

of the United States

Neeraj Kaushal

Robert Kaestner

Cordelia Reimers

a b s t r a c t

We investigated whether the September 11, 2001 terrorists’ attacks had any effect on employment, earnings, and residential mobility of first- and second-generation Arab and Muslim men in the United States. We find that September 11thdid not significantly affect employment and hours of work of Arab and Muslim men, but was associated with a 9-11 percent decline in their real wage and weekly earnings, with some evidence that this decline was temporary. The adverse earnings effects were strongly linked to hate crime incidence. Estimates also suggest that the terrorists’ attacks reduced intrastate migration of Arab and Muslim men.

I. Introduction

A large number of Arabs and Muslims living in the United States be-came victims of hate crime and were subjected to ethnic and religious profiling after the September 11th, 2001 terrorists’ attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon

(Human Rights Watch 2002). The 2001 FBI annual hate crime report, and state and local agency data showed a significant increase in violence against these groups and

Neeraj Kaushal is an assistant professor of social work, Columbia University; Robert Kaestner is a professor of economics, University of Illinois at Chicago, and Cordelia Reimers is a professor of economics, Hunter College of the City University of New York. The authors thank the Russell Sage Foundation for providing partial funding for the project. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s conference on Immigration in the United States, April 29, 2005. The authors thank the participants in that conference and also seminar participants at Columbia University School of Social Work, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, RAND, and the University of Illinois at Chicago for their helpful suggestions. The data used in this article can be obtained beginning October 2007 through September 2010 from Neeraj Kaushal, 1255 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, New York 10027 <nk464@columbia.edu> [Submitted March 2006; accepted July 2006]

ISSN 022-166X E-ISSN 1548-8004Ó2007 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

those perceived to be like them such as Sikhs.1Polls conducted by various advocacy groups found that 20 to 60 percent of American Muslims and Arabs said that they personally experienced discrimination after the September 11th attacks (Human Rights Watch 2002). In addition, Arabs and Muslims have reported an increased incidence of discrimination at work since the terrorists’ attacks. In the first eight months after the attacks, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) received 488 complaints of September 11th-related employment discrimina-tion, of which 301 involved persons who were fired from jobs (U.S. EEOC 2002).

While it seems clear that the events of September 11thgenerated increased hostil-ity toward Arab and Muslim persons, it remains unknown whether this greater pre-judice resulted in economic harm, as there is little research on this question.2Davila and Mora (2005) used data from the American Community Survey to examine whether the wages of young, Middle Eastern Arab, African Arab, and Afghan, Iranian, and Pakistani men who work full time declined between 2000 and 2002. They find a large (more than 20 percent) relative decline in the wages of Middle Eastern Arab men, but, surprisingly, little change in the relative wages of Afghan, Iranian, and Pakistani men even though this group is arguably more likely to have been adversely affected by discrimination than Middle Eastern Arab men are. Davila and Mora (2005) also find an unexpected improvement in relative wages of African Arab men. The mixed nature of these findings suggests more study of the issue is warranted. Accordingly, the objective of this study is to investigate whether Septem-ber 11th affected the employment, earnings, and residential mobility of first- and

second-generation immigrants from countries with predominantly Arab or Muslim populations. For convenience, we will refer to these persons as Arabs and Muslims. Our study is significant because besides documenting whether increased prejudice against Arabs and Muslims resulted in labor market discrimination, our analysis also will contribute in a more general way to the literature concerned with identifying whether and how ethnic or racial prejudice turns into labor market discrimination (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004; Darity and Mason 1998). To preview our results, we find that the relative wages and weekly earnings of Arab and Muslim men de-clined by approximately 9–11 percent subsequent to September 11th, but that this decline is significantly smaller in more recent periods. We do not find significant decreases in employment or hours, suggesting a relatively inelastic supply curve. We also find that the earnings decline was broad-based and of the same general mag-nitude for those with different education levels, nativity status, and residential loca-tion (that is, ethnic enclave). However, earnings decreases were larger in areas with more reported hate crime related to religious, ethnic, or country of origin bias.

1. According to the 2001 FBI hate crimes report, the number of anti-Muslim hate crimes in the country rose from 28 in 2000 to 481 in 2001. A Human Rights Watch report (2002) cites data from local and state agencies that indicate growing hate crime against Muslims. In Chicago, for instance, the police department reported 51 anti-Muslim hate crimes during September-November 2001, as compared with only four such cases during the entire year 2000. In Los Angeles County, there were only 12 hate crime cases against peo-ple of Middle Eastern descent in 2000, as compared with 188 in 2001 (Human Rights Watch 2002). 2. See Bramet al.(2002a, 2002b), Gaelaet al.(2002), Citizen’s Committee for Children (2002), Foner (2005), Chernick (2005), and Mollenkopf (2005) for the effects of the September 11th attacks on New York residents.

Finally, we find some evidence that September 11thwas associated with a decrease in intrastate migration of Arab and Muslim men.

II. Theoretical Considerations

The terrorists’ attacks on September 11thtriggered ill feelings toward Arabs and Muslims, and this new (or increased) prejudice may have adversely af-fected their labor market outcomes. Such prejudice could have been manifested in the labor market in a variety of ways. Employers and managers may have hired fewer, or fired (laid off) more, Arabs and Muslims than would otherwise have been the case (U.S. EEOC 2002). Employee discrimination also is possible. Non-Muslim employees may have reduced their cooperation with Arab and Muslim coworkers, which may have harmed employee productivity, particularly that of Arabs and Mus-lims. Finally, customer prejudice may have lowered the productivity of Arab and Muslim employees in occupations with direct customer contact (for example, retail, self-employment), if customers shied away from doing business where they had to interact with an Arab or Muslim person (Borjas and Bronars 1989; Nardinelli and Simon 1990). In sum, greater prejudice toward Arab and Muslim persons may have resulted in a decrease in the demand for Arab and Muslim labor, which would have lowered their wages and may have reduced their employment (or hours) depending on the elasticity of supply of labor.3Empirical evidence from other studies suggests that the elasticity of supply is relatively small, so employment effects may not be very large (Killingsworth 1983; Mroz 1987; Blundell and MaCurdy 1999).

Obviously, if prejudice toward Arab and Muslim persons resulted in discrimina-tion, we would expect larger discriminatory effects where this prejudice is greater. For example, there may be greater prejudice toward first generation Arab and Mus-lim persons than toward U.S.-born Arabs and MusMus-lims, as the latter are likely to be culturally and behaviorally more like other native-born persons (that is, assimilated). Similarly, highly educated Arab and Muslim persons may be less affected than the less educated, if education results in greater assimilation. And the degree of preju-dice and discrimination may differ across localities if prejupreju-dice depends on previous social contact, because the Arab and Muslim population is geographically concen-trated. Finally, there may be less prejudice toward women because women are not associated with terrorism.

Discrimination may cause other behavioral responses that would mediate any la-bor market effects. In particular, discrimination may affect location choices of Arabs and Muslims. Emigration from the United States (or reduced immigration), by de-creasing the supply of Arab and Muslim labor, would attenuate the wage effects of a decrease in the demand for their labor, and the attenuating effects would be larger if emigration were selective—if those most affected were more likely to

3. September 11thalso may have decreased the demand for Arab and Muslim employees because of sta-tistical discrimination. Employers may perceive that hiring or promoting Muslim and Arab workers is risky, either because of security concerns or uncertainty over the permanency of Arab and Muslim immigrants’ stay in the United States (Swarns and Drew 2003; Swarns 2003).

emigrate. Moreover, such a decrease in supply would not be detected by an analysis of individual labor supply since we cannot observe outcomes for those who emigrate. The upshot is that emigration will tend to bias estimates of the discriminatory effects of September 11thtoward finding no effect on wages and employment.4

Discrimination also may affect internal migration because of changes in the geo-graphic distribution of available jobs and wages. For example, Arabs and Muslims may move within the United States in search of a less hostile environment with better employment opportunities. On the other hand, greater prejudice that broadly reduces earning opportunities will reduce migration, particularly if costs of migration remain unchanged, or increase because of uncertainty. Thus, Arabs and Muslims may be re-luctant to leave an ethnic enclave (or current location) that provides security in un-certain times. Like emigration, internal migration of Arabs and Muslims may attenuate any discriminatory wage and employment effects of September 11th; but

in this case, we can observe the changes in migration and the labor market outcomes of the migrants. Therefore, the wage and employment changes we obtain would be a combination of migration effects and local labor market effects.

III. Research Design and Statistical Methods

A. Labor Market Outcomes

The first objective of our analysis is to obtain estimates of the effect of the September 11th attacks on the employment and wages of Arab and Muslim persons living in the United States. To isolate the effects of the September 11thattacks from seasonal and cyclical

var-iables, changes in the demographic and geographic composition of the sample, and un-observed time-varying factors, we use a multivariate regression analysis to control for observable factors and a comparison-group approach to control for unobservable factors. Data for this analysis come from the 1998 to 2004 Current Population Survey monthly outgoing rotation groups files (CPS-ORG). We describe these data in more detail below. We want to obtain ‘‘causal’’ estimates of the effect of the September 11th terror-ists’ attacks. Obviously, the recession that began in March 2001 is one potential confounding factor. To address this and other unmeasured factors, we adopt a comparison-group approach, which is also referred to as a difference-in-differences (DD) procedure. To implement this approach, we select a group that is similar to Arabs and Muslims in other respects, but is unlikely to be affected by the animosity engendered by the September 11th attacks. The identifying assumption of the DD procedure is that in the absence of the September 11thattacks, persons in the comparison group would have had labor market experiences similar to those of Arabs and Muslims. Therefore, we can use pre- to post-September 11thchanges in labor market outcomes of the comparison group to eliminate the effect of unmeasured factors from the pre- to post-September 11thchanges in labor market outcomes of Arabs and Muslims.

Estimates of the effect of September 11thbased on the comparison-group approach may be obtained using a pooled sample of Arabs and Muslims and persons in the

comparison group. The regression model using this pooled sample, estimated sepa-rately for men and women, is given by:

Yist¼a0+a1Septt +a2Trist +a3ðSepttTristÞ+XistG+ðXistTristÞG˜

+ZstL+ðZstTristÞL˜+dt+tm+ð˜tmTristÞ+gs+ðg˜sTristÞ+uist

ð1Þ

In Equation 1,Yistis a labor market outcome of personiin statesand timet

(mea-sured in months during the period September 1998- September 2004). The variable Septt is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the observation is taken from the

post-September 2001 period, and zero otherwise. Other variables in Equation 1 are as fol-lows:Trist is equal to 1 if the individual is an Arab or Muslim, and zero otherwise;

Xistis a vector of individual characteristics that include age, education, race, country

of birth, citizenship status, number of years lived in the United States, marital status, occupation, and industry type;5Zstconsists of two variables, the monthly state

unem-ployment rate and annual state per-capita income;6dtis a monthly time trend

spec-ified as a cubic function, which is intended to control for business-cycle trends in labor market outcomes during the period of the study;tmis a set of month-of-year

dummy variables to control for seasonality;gsare fixed effects for state of residence; anduist represents unmeasured, possibly time-varying, characteristics.

We study four standard labor market outcomes: whether employed last week, hours worked last week (including zeros for those not employed), and for those employed, log real hourly earnings and log real weekly earnings. We also investigate whether September 11th affected the likelihood that Arabs and Muslims are

self-employed or work in retail trade—occupations for which customer discrimination may be particularly important.

Equation 1 reflects the least restrictive specification, as all effects are allowed to differ by target-comparison group status, except for the effect of time factors (dt) that

are restricted to be the same for the target and comparison groups. The parametera3

measures the difference-in-differences effect of September 11thon the labor market outcomes of Arabs and Muslims. To assess the validity of the comparison-group ap-proach, we estimate Equation 2, which is similar to Equation 1 but allows the effect of the cubic trend to be different for the target and comparison groups.

Yist¼a0+a1Septt+a2Trist +a3ðSepttTristÞ+XistG+ðXistTristÞG˜+ZstL

+ðZstTristÞL˜+dt+ðd˜tTristÞ+tm+ð˜tmTristÞ+gs+ðg˜sTristÞ+uist

ð2Þ

If ˜dt¼0, that will indicate that time trends in log wages (and the other outcomes:

employment, hours, and log weekly earnings) for the target and comparison groups are equal, conditional on the other covariates. Such a finding is consistent with the underlying assumption of the difference-in-differences approach, which is that un-measured trends in log wages correlated with the September 11thdummy variable are equal for the treatment and comparison groups (conditional on the other co-variates). In the analysis for men, in all cases, we cannot reject ˜dt¼0 (joint test

5. Occupation and industry are introduced only in the analyses of real wages and weekly earnings because they are only available for persons who are in the labor force or who worked in the past year. 6. The state unemployment rate and per capita income are excluded from analyses of employment and hours worked per week because these variables may be endogenous with respect to these two outcomes.

of coefficients), although standard errors are relatively imprecise.7More importantly, restricting the cubic trend to be the same for the target and comparison groups has no substantive effect on the difference-in-differences estimates for men, which is consistent with statistical tests that failed to reject the equality of the trend.8

How-ever, in the analysis for women, we can reject ˜dt¼0 for weekly hours worked

and log weekly earnings, but not for the other outcomes, suggesting that we may not have a good research design for women.

Equation 1 restricts the effects of September 11thto be the same for all persons in the target group, but as noted above, any discriminatory effects of September 11th will differ by the degree of prejudice. Therefore, we investigate whether the effect of September 11thdiffered by characteristics that are arguably correlated with the de-gree of prejudice against Arabs and Muslims—specifically, whether an individual is foreign-born (first generation); whether he is highly educated; whether he lives in a state with high Arab and Muslim density; and whether he lives in a state with a high incidence of reported religious, ethnic, or country-of-origin hate crime. The specifi-cation of the model that allows for heterogeneous effects is:

Yist¼a0+a1Septt++ k

bkGrk++ k

bsðSepttGrkÞ+a2Trist+a3ðSepttTristÞ

++

k

bgðTristGrkÞ++ k

bktðSepttGrkTristÞ+XistG+ðXistTristÞG˜

+ZstL+ðZstTristÞL˜+dt+tm+ð˜tmTristÞ+gs+ðg˜sTristÞ+uist

ð3Þ

Equation 3 differs from Equation 1 in only one respect: it allows the effects of September 11thto differ across groups within the target population. As noted, groups are defined on the basis of nativity, education, geography, and incidence of hate crimes. The hate crime data comes from FBI reports of hate crimes motivated by eth-nic, national origin or religious factors.

B. Residential Mobility

September 11thalso may have affected location choices, if it resulted in

discrimina-tion that altered the geographic distribudiscrimina-tion of available jobs and wages.9To inves-tigate whether September 11thaffected the location choices of Arabs and Muslims, we examined the effect of September 11thon the following changes in residence:

• moved to a different state;

• moved within the same state;

• nonmovers.

7. In the analysis for men, thep-value of the hypothesis, ˜dt¼0 (joint test of coefficients), are 0.55 for em-ployment; 0.11 for weekly hours worked, 0.39 for log real wage, and 0.93 for log weekly earnings. In the analysis for women, the correspondingp-values are 0.64 for employment, 0.02 for weekly hours worked, 0.65 for log real wage, and 0.02 for log weekly earnings.

8. Separate estimates for the target and comparison groups that verify this finding can be obtained from the authors on request.

9. September 11thalso may have affected emigration, but lack of data prevents us from investigating this issue. Although the Department of Homeland Security keeps an account of all documented arrivals, there is no account of those who leave the country during a given period.

And to investigate whether September 11thcaused greater migration to avoid dis-crimination, we also examined the effect of September 11thon the following changes in residence of Arabs and Muslims:

• moved to a state with greater reported hate crime as compared with the state of origin;

• moved to a state with lower hate crime as compared with the state of origin;

• and ‘‘nonmovers,’’ which includes intrastate movers.

To obtain estimates of the effect of September 11thon migration, we used the same comparison-group approach that we use for labor market outcomes. The estimation equation in this case is:

ln pict pi0t

¼m0+m1Trist+m2Septt+m3ðTristSepttÞ+XijtG+uZst21+xs+uisjt

ð4Þ

wherePict is the probability that individualimakes residential choicec(one of the

three categories) withPi0t as the reference category, which consists of nonmovers.

The model includes (origin) state fixed effects (xs); unemployment rate and per capita income in the origin state last year (Zst21); and individual characteristics

(Xijt). We use a multinomial logit regression procedure to estimate this model, and

report the marginal effects with the corresponding standard errors.

C. Validity of Comparison Group

An ideal comparison group should satisfy two conditions: Its members should not be affected by September 11th-related prejudice, and unobserved factors that are contemporaneous with September 11th should have the same effect on it as on the target group. We describe the composition of the comparison group below. The first condition is relatively easy to meet. To assess whether our comparison group meets the second condition, we conduct two pseudointervention analyses using data prior to September 11, 2001. We choose two dates for these pseudoin-tervention events: September 1999 and April 2000, which is the date when the employment/population ratio peaked nationally in the United States. Difference-in-differences estimates obtained using pseudointervention dates should be zero if the comparison group is valid. We present these results in detail below, but here we note that in the analysis for men, difference-in-differences estimates pertaining to the pseudo interventions were all close to zero and statistically insignificant. Among women, however, difference-in-differences estimates were often statistically significant and large.

IV. Data

We use two different data sets in the analysis. To investigate the ef-fect of September 11thon the labor market outcomes of Muslims and Arabs, we use the Current Population Survey monthly outgoing rotation groups files (CPS-ORG) for September 1997 to September 2005. One advantage of the CPS-ORG is that it provides relatively large sample sizes, which are important given our interest in a

narrowly defined population—persons of Arab and Muslim descent. However, it does not provide information on the state of residence a year ago, so for the analysis of residential mobility (migration) we use the March CPS for 1999-2004.

The CPS provides information on respondents’ and their parents’ nativity, which is used to define the target and comparison groups. Ideally, we would like to include in our target group all persons of Arab and Muslim heritage, but this is not possible due to data limitations. Instead, we select first- and second-generation immigrants from all but three of the countries on the special registration list of the Department of Justice.10 These countries are Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.11 We have excluded North Korea because North Koreans are unlikely to be a victim of September 11th-related discrimination. Somalia and Eritrea are excluded because

these countries could not be identified in our data. The special registration list excludes Turkey and Malaysia, countries with predominantly Muslim populations. Arguably, Muslims from Turkey and Malaysia are as likely to be affected by Septem-ber 11th-related discrimination as other Muslims are. Therefore, we also include first-and second-generation immigrants from Malaysia first-and Turkey.12

Clearly, not all persons in our target group are Arab and Muslim. Nor are all Arab and Muslim persons in this group easily identified as such. These issues are relevant to the interpretation of the estimated effects of September 11th, since they are average effects for the group, and only a portion of the group are likely to be affected.

We experiment with two comparison groups, both of which are likely to be unaf-fected by September 11th. Comparison Group I consists of first- and second-generation immigrants, excluding those from countries in the target group, India, Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and what the CPS categorize as ‘‘other Africa.’’ We exclude Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean so that this comparison group is similar to the target group in terms of the key determinants of labor market outcomes such as ed-ucation.13We exclude India because, although Indians were excluded from the special

registration, 12 percent of the Indian population is Muslim and there also have been reports of Indians of Sikh religion becoming objects of hate crime since the September 11thattacks (Human Rights Watch 2002). We test the sensitivity of our results by using

10. In October 2002, the Department of Justice announced a special registration program within the Na-tional Security Entry-Exit Registration System that required nonimmigrant men (that is, noncitizen men without green cards) from Iran, Libya, Sudan, and Syria to register with the Department of Homeland Se-curity by December 2002. The list of ‘‘special registration’’ countries was expanded to 25 by December 2002, with the deadline for registration extended to April 2003.

11. The CPS identifies Turkey, Malaysia, and 12 of the 24 predominantly Arab or Muslim countries that were listed for special registration; 10 others are classified into two regions: the rest of North Africa and the rest of the Middle East. The CPS classifies persons born in Somalia and Eritrea as ‘‘other Africans.’’ Since many countries also classified by the CPS as ‘‘other Africa’’ are not predominantly Arab or Muslim, we exclude persons from ‘‘other Africa’’ from the target and comparison groups.

12. We do not include Indians in the target group because a relatively small fraction of the Indian popu-lation is Muslim—12 percent. We also exclude them from the comparison group.

13. We repeated the analysis restricting the comparison group to first-generation individuals. The results were similar to those reported below. We also repeated the analysis with a comparison group that included the first and second generations from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, in addition to Compar-ison Group I. Again, the estimated results did not differ much.

another comparison group—Comparison Group II—that consists of all U.S.-born per-sons other than those in the target group and 1stand 2ndgeneration Asian Indians.14

We restrict our samples to men and women aged 21 to 54. For the U.S.-born Com-parison Group II, we select a 25 percent random sample to reduce the computational burden associated with the large number of observations for this group. The target group is more concentrated geographically within the United States than the two comparison groups. This could invalidate the comparison-group approach if business cycle effects vary by state. To make the groups more geographically similar, we limit our sample to 20 states in which 85 percent of the target group lives.15

The two CPS data sets have all the demographic information required for the anal-ysis. The CPS-ORG data contain age, gender, marital status, race, education, birth-place, parents’ birthbirth-place, when arrived in the United States, citizenship status, occupation, industry, and state of residence, in addition to the four labor market out-comes.16The March CPS has the location of residence one year ago and occupation and industry of work last year. Monthly state unemployment rates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and state per-capita income from the Bureau of Economic Analysis are merged with the CPS individual-level data. Appendix1 contains a list of all var-iables used in the analysis with their definitions.

Data on hate crime come from the FBI hate crime reports for 1997–2004.17We combine incidents of hate crime motivated by religious, ethnicity, or national origin bias because these kinds of hate crimes are most relevant to September 11th-related discrimination. These data are merged with the CPS-ORG data files by state and year. Data from the 2000 Census (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2003) are used to es-timate the Arab population, which is used to compute hate crimes/discrimination per Arab in each state. State population from the 2000 Census is employed to compute per capita hate crimes/discrimination incidents.

V. Results

A. Descriptive Analysis: Labor Market Outcomes

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the samples used in the analysis for the period from September 1998 to September 2004.18Several points merit comment. First, the

14. The target group in our analysis were born in following countries: 15 percent in Iran, 12 percent in Pakistan, 7 percent each in Lebanon and Bangladesh, 5 percent each in Turkey and Iraq; 4 percent in Indo-nesia; 3 percent each in Syria and Afghanistan; 7 percent in rest of the Middle East, and 4 percent in rest of North Africa. About 14 percent were U.S.-born and the remaining from other countries. The comparison Group 1 comprises 6 percent from the Philippines, 4 percent each from China, Vietnam, South Korea, and Colombia; 3 percent each from Canada and Poland, and 2 percent each from Germany, Russia, England, Taiwan, and Italy; about 35 percent are U.S.-born and the remaining are from other countries. 15. Analyses using data for the entire country suggest, however, that this restriction has virtually no effect on the estimates.

16. CPS-ORG does not provide earnings data on self-employed persons.

17. FBI hate crime reports suffer from bias due to nonsubmission of reports by local law enforcement agen-cies and differences in the accuracy with which agenagen-cies classify and report bias crime (McDevittet al. 2005). There is also concern that Arabs and Muslims are less likely to report hate crime to a state agency. In our 20 state sample, all states reported nonzero incidents of hate crime motivated by religion, ethnicity, and national origin during 1997–2004, except for New Hampshire in 1997, when the state did not partic-ipate in the FBI Uniform Crime Report program.

18. Data for September 2001 is dropped from all analyses.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics: CPS-ORG, September 1998 to August 2001 and October 2001 to September 2004

Men Women

Target Group

Comparison Group 1

Comparison Group 2

Target Group

Comparison Group 1

Comparison Group 2

Education

<12 years 0.06 0.09*** 0.08*** 0.08 0.09 0.07***

¼12 years 0.18 0.25*** 0.32*** 0.22 0.25*** 0.30***

¼13–15 years 0.23 0.25*** 0.29*** 0.25 0.25 0.32***

>15 years 0.53 0.41*** 0.31*** 0.45 0.40*** 0.31***

Age 37 38*** 38*** 36 38†*** 38***

Labor market outcomes, pre-September 11, 2001

Currently employed 0.84 0.87*** 0.88*** 0.54 0.71*** 0.76***

Hours worked last week 36 37** 37*** 19 25*** 27***

Log real wage 2.76 2.81*** 2.81*** 2.57 2.60 2.58

Log real weekly earnings 6.49 6.56*** 6.57*** 6.16 6.20 6.16

284

The

Journal

of

Human

Labor market outcomes, post-September 11, 2001

Currently employed 0.83 0.86*** 0.85*** 0.58 0.70*** 0.75***

Hours worked last week 35 35 36 20 25*** 26***

Log real wage 2.79 2.84*** 2.83*** 2.61 2.64 2.62

Log real weekly earnings 6.50 6.58*** 6.58*** 6.14 6.23*** 6.14

Married 0.58 0.60* 0.57* 0.68 0.63*** 0.56***

Citizen (including 2ndgeneration) 0.56 0.65*** 1.00*** 0.57 0.65*** 1.00***

Proportion 1stgeneration 0.86 0.61*** – 0.81 0.63*** –

Proportion 2ndgeneration 0.14 0.39*** – 0.19 0.37*** –

Proportion 2 + generation – – 1.00 – – 1.00

Living in the United States

< 5 Years 0.17 0.12*** – 0.20 0.13*** –

¼5–10 Years 0.14 0.09*** – 0.13 0.09*** –

>10 years (including 2ndgeneration) 0.69 0.79*** – 0.67 0.78*** –

Number of observations 4,322 38,572 62,920 3,503 42,063 68,756

Number of observations in earnings analysis 2,715 27,550 46,148 1,685 26,245 46,566

Notes: The sample is restricted to individuals aged 21–54 who live in the 20 states where 85 percent of Arab and Muslim U.S. residents live. The Target Group consists of individuals who were born in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, and other countries under the broad heading of Middle East (excluding Israel), and North Africa. It also includes individuals with at least one parent born in the above-mentioned countries. Comparison Group I consists of first and second generation immigrants excluding those from Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, India, other Africa, and the target group; and Comparison Group II consists of the U.S.-born other than those in the target group or first and second generation Indians. * indicates that the mean value for the target group is statistically different from the mean value for the comparison group at the followingp-values: *0.05<p¼<0.1, ** 0.01<p¼<0.05, ***p¼<0.01.

Kaushal,

Kaestner

,

and

Reimers

average education of the target group (Arabs and Muslims) is higher than the average education level of the two comparison groups. For instance, 53 percent of the men in the target group have a college degree, compared with only 41 percent among the ison group of other first-and second-generation men and 31 percent among the compar-ison group of U.S.-born men. Second, on average, men and women in the target group are one to two years younger than men and women in the two comparison groups. Third, the pre-September 11themployment rate among men in the target group is two to three percentage points less than that of the comparison groups; and on average, men in the target group worked zero to one hour less per week, which implies that among those who work, men in the target group tend to work slightly more hours per week than men in the comparison groups. Among women, those in the target group worked sig-nificantly less, and fewer hours per week even among those who work. Fourth, despite their higher education levels, men in the target group earned less than men in the com-parison groups both before and after September 11th. Fifth, compared to Comparison Group I, a much larger proportion of the target group were foreign-born and a smaller proportion of the target were citizens (including the U.S.-born).

B. Multivariate Analysis: Labor Market Outcomes

Table 2 presents the results of the analysis of labor market outcomes in four panels, one for each of the four outcomes of interest. In each panel, two rows of difference-in-differences estimates, corresponding to the two comparison groups, are presented for men and women. Each column of each panel shows estimates from a different model specification, which is described at the bottom of the table. The key difference be-tween models is the controls for time effects. Three specifications are used: cubic trend, month dummy variables (a total of 72 dummy variables), and state-month dummy variables (a total of 1,440 dummy variables). In addition, in the wage and weekly earnings models, we show estimates from a model that excludes industry and occupation dummy variables to assess whether any changes in wages and earn-ings are correlated with changes in the industry and occupation distribution, which is a potentially important mechanism through which discrimination may operate. Ro-bust standard errors, clustered by state and target group (40 clusters), are in paren-theses (Huber 1967; White 1980).

Estimates in Panel 1 indicate that September 11thhad no effect on the employment of Arab and Muslim men; estimates are small—always less than one percentage point—and not statistically significant. Among women, however, estimates indicate that September 11thsignificantly increased the employment rate of Arabs and Mus-lims by three to four percentage points, which is surprising given that greater prej-udice would be expected to reduce employment. Notably, estimates in Panel 1 are not sensitive to the choice of comparison group or model specification. In fact, tests of the models indicate that we cannot reject the cubic trend specification. Consistent with the employment effects, estimates in Panel 2 indicate that September 11thhad no statistically or materially significant effect on the hours of work of Arab and Mus-lim men, but September 11this associated with approximately a one hour (5 percent) increase in hours of work of Arab and Muslim women. Again, estimates are not sen-sitive to choice of comparison group or model specification.

Table 2

Difference-in-differences Estimates of the Effect of September 11thon Employment & Earnings of Arabs and Muslims (CPS September 1998- August 2001; October 2001-September 2004)

Panel 1: Currently Employed Panel 3: Log (Real Hourly Earnings)

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Men

DD (Target-comparison group I)

20.002 20.002 0.003 20.112* 20.095* 20.096* 20.098*

(0.013) (0.013) (0.012) (0.057) (0.049) (0.049) (0.044)

DD (Target-comparison group II)

0.006 0.006 0.003 20.123** 20.092* 20.093* 20.086

(0.013) (0.013) (0.012) (0.057) (0.051) (0.052) (0.051)

Women

DD (Target-comparison group I)

0.043** 0.044** 0.044** 0.046 20.004 20.003 0.011

(0.020) (0.020) (0.019) (0.061) (0.058) (0.059) (0.048)

DD (Target-comparison group II)

0.038** 0.038* 0.037 0.013 20.018 20.018 20.035

(0.021) (0.021) (0.022) (0.064) (0.059) (0.059) (0.063)

Men Panel 2: Hours Worked Last Week Panel 4: Log (Real Weekly Earnings)

DD (Target-comparison group I)

0.194 0.179 0.282 20.129* 20.110* 20.111* 20.104*

(0.636) (0.644) (0.557) (0.069) (0.057) (0.058) (0.053)

DD (Target-comparison group II)

0.306 0.306 0.121 20.143** 20.114* 20.115* 20.111**

(0.623) (0.623) (0.538) (0.070) (0.059) (0.061) (0.055)

(continued)

Kaushal,

Kaestner

,

and

Reimers

Table 2 (continued)

Panel 2: Hours Worked Last Week Panel 4: Log (Real Weekly Earnings)

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Women

DD (Target-comparison group I)

1.106* 1.127* 1.032* 20.051 20.092 20.092 20.039

(0.631) (0.631) (0.590) (0.089) (0.078) (0.080) (0.072)

DD (Target-comparison group II)

1.112* 1.115* 1.092* 20.063 20.088 20.084 20.096

(0.635) (0.634) (0.641) (0.093) (0.081) (0.080) (0.084)

Model includes

Occupation & industry controls

No No No No Yes Yes Yes

Cubic trend Yes No No Yes Yes No No

Month effects

(72 dummy variables)

No Yes No No No Yes No

Month*state effects (1,440 dummy variables)

No No Yes No No No Yes

Note: Figures in each cell are from separate regressions. Robust standard errors clustered around state and target (or comparison) group are in parentheses. All regressions control for demographic factors, namely, age, education, race, marital status, number of years lived in the United States, citizenship status, and whether foreign-born; state fixed effects, and month of the year effect. Regressions with log real wage and log real weekly earnings also control for state unemployment rate and per capita income. All analysis using Comparison Group I also adjusts for the country of birth, as statistical tests do not permit dropping country fixed effects. Cubic trends, month effects and month*state effects are restricted to be the same for the target and comparison groups, all other controls are introduced separately for the two groups. See Table 1 for sample definition and sample sizes. *0.05<p¼<0.1, ** 0.01<p¼<0.05, ***p¼<0.01.

288

The

Journal

of

Human

and statistically significant wage effects for men; estimates indicate that September 11this associated with between a 9 to 12 percent decrease in wages, and a 10 to 14 percent decrease in weekly earnings, of Arab and Muslim men. Estimates are not sensitive to choice of comparison group or to model specification and again, we cannot reject the cubic trend specification. There is some evidence that pre- and post-September 11thwage changes are correlated with changes in the industry and occupation distributions of Arab and Muslim men. Estimates of the effect of Septem-ber 11thobtained from models that include controls for industry and occupation are 15 to 25 percent smaller than estimates obtained from models that exclude such con-trols. The sensitivity of the estimates of the effect of September 11thto inclusion of industry and occupation controls suggests a potential causal mechanism. The indus-try and occupational distribution of Arab and Muslim men changed pre- and post September 11thand as a result, earnings were adversely affected. Therefore, it is pos-sible that greater prejudice reduced employment opportunities for Arab and Muslim men and forced them to make less desirable choices, resulting in earnings declines. We investigate this possibility and other potential mechanisms below.

Estimates of the effect of September 11thon the wages and weekly earnings of women are mixed. Wage estimates are not statistically significant, and for the most part small in magnitude. The exception is estimates from Model 1 using Comparison Group I, which shows a positive wage effect of September 11thof 5 percent. How-ever, once industry and occupation controls are included, the positive wage effect is greatly reduced to less than 1 percent. In contrast, estimates of the effect of Septem-ber 11thon Arab and Muslim women’s weekly earnings are negative, and relatively large, although not statistically significant. These are anomalous findings that are in-consistent with the wage estimates and the increase in employment and hours that was associated with September 11th.

C. Verification of Research Design

The credibility of our analysis depends on the validity of the comparison groups and on whether emigration of Arabs and Muslims after September 11thwas widespread.

We address the first issue, namely whether trends in labor market outcomes of the target and comparison groups are same (apart from the effect of September 11th and conditional on other measured covariates), by conducting two analyses of pseudo interventions to test the underlying assumption of the difference-in-differences re-search design. First, using CPS-ORG data from September 1997 to August 2001, we obtain difference-in-differences estimates using two pseudo intervention dates: September 1999, exactly two years before the terrorists’ attacks, and April 2000, the date when the employment/population ratio peaked nationally in the United States. We obtain estimates of the effects of the pseudointerventions using a model that controls for the effect of time using a cubic trend, as tests could not reject this model specification vis-a`-vis month, or state-month, dummy variables. If the compar-ison group approach is valid, we expect estimates of the effect of these two pseudoin-terventions to be close to zero and not statistically significant. The results of the pseudointervention experiment are presented in Table 3.

For men, estimates in Table 3 provide validation for the differences-in-differences research design. All estimated coefficients are small in magnitude and statistically

Table 3

Validation Tests of the Difference-in-differences Methodology: CPS-ORG, September 1997-August 2001

Currently Employed

Hours Worked

Log (Real Hourly Earnings)

Log (Real Weekly Earnings)

Pseudointervention 1 Intervention in Sept 1999 Men

DD (Target-comparison group I) 20.002 20.571 0.008 20.015

(0.023) (0.896) (0.037) (0.039)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 0.004 20.201 20.003 20.020

(0.023) (0.874) (0.032) (0.033)

Women

DD (Target-comparison group I) 0.009 1.865** 20.036 0.174***

(0.019) (0.905) (0.057) (0.064)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 0.013 1.786* 20.025 0.152**

(0.020) (0.938) (0.057) (0.070)

290

The

Journal

of

Human

Pseudointervention 2 Intervention in April 2000 Men

DD (Target-comparison group I) 0.005 0.339 20.014 0.028

(0.022) (0.842) (0.052) (0.044)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 0.011 0.709 20.015 0.045

(0.021) (0.819) (0.053) (0.047)

Women

DD (Target-comparison group I) 0.013 1.573 0.099** 0.177**

(0.020) (0.986) (0.044) (0.081)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 0.018 1.582 0.108** 0.173**

(0.022) (1.011) (0.042) (0.078)

Notes: Robust standard errors clustered around state and target (or comparison) group are in parentheses. Each figure in Columns 1 and 2 is a difference-in-difference estimate based on Model 1 for employment and hours in Table 2 and each figure in Columns 3 and 4 is a difference-in-difference estimate based on model 2 for log (hourly earnings) and log (weekly earnings) in Table 2. *0.05<p¼<0.1, ** 0.01<p¼<0.05, ***p¼<0.01.

Kaushal,

Kaestner

,

and

Reimers

insignificant. However, for women, many estimates are statistically significant and relatively large. These results suggest that the comparison group approach is not valid for women. The inadequacy of the comparison groups in the case of women is consistent with the relatively large differences in sample means of observed char-acteristics between the target and comparison groups in Table 1. The relatively poor quality of the comparison groups also may explain the anomalous results found in Table 2 for women. Based on this evidence, we do not believe that estimates for women are credible and we restrict additional analyses to men.

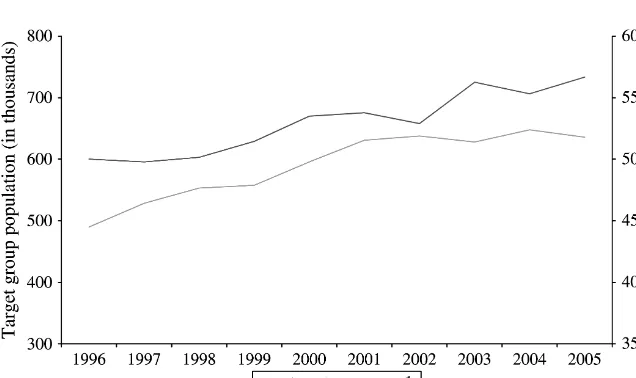

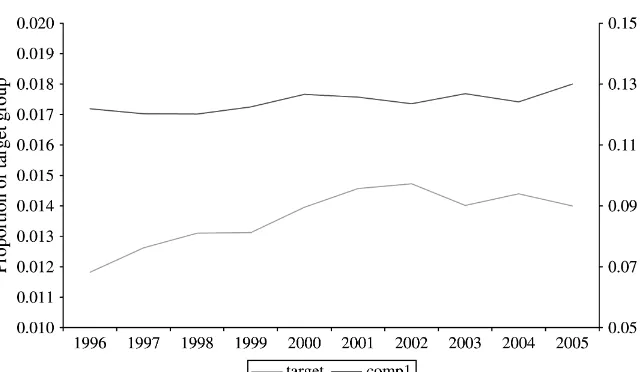

As mentioned earlier, events in the aftermath of the September 11thattacks may have triggered emigration by the target group. To assess whether large-scale emigra-tion occurred during the post-September 11thperiod of our study, we estimated the population of the target group and Comparison Group I in the 20 states that we use in the analysis, using annual averages of monthly CPS-ORG data. Figures 1 and 2 pre-sent time-series graphs of the level and proportion of the population in our target group and Comparison Group I. These graphs show that the number of Arab and Muslim men in the population leveled off from 2001 to 2005 after an upward trend, and their proportion has fallen slightly since 2002. In comparison, the share of Com-parison Group I has been more or less constant (or slightly rising) during 1996–2005. It is not possible to measure the actual level of emigration by the target group during this period since the Department of Homeland Security does not collect data on who leaves the country. Overall, these graphs, while less than definitive, do not suggest that emigration was a significant problem. Therefore, we believe it is reasonable

Figure 1

Trends in population of target and comparison groups (CPS 1996-2005; men aged 21 to 54; population restricted to the top 20 states where the target group lives)

to work under the assumption that any effects of September 11ththat we measure are not significantly affected by emigration.

D. Timing of the Effects of September 11th

Earlier we found that September 11thwas associated with a significant decline in Arab and Muslim men’s wages. Presumably, this was a result of discrimination, but discrimination may diminish over time, as the shock of the events of September 11thwears off and prejudice against Arabs and Muslims return to previous levels. However, during most of 2002 and 2003, the Department of Homeland Security (http://www.whitehouse.gov/homeland/archive.html) determined the overall threat to national security from a terrorists’ attack to be at an ‘‘elevated yellow’’ (significant risk of terrorist attack) or ‘‘high orange’’ (high risk of terrorist attacks) and newspa-per reports continue to suggest a significant amount of ill will toward Arabs and Muslims.19

To investigate this issue, we reestimate Model 2 of Table 2 for wages and weekly earnings, but allow the effect of September 11thto change over time. These results are presented in Table 4. Estimates suggest very little diminution of the effects of

Figure 2

Trends in proportion of target and comparison groups in US population (CPS 1996-2005; men aged 21 to 54; population restricted to the top 20 states where the target group lives)

19. Newspaper reports suggest that ill feelings toward Arabs and Muslims have remained high since the September 11thattacks. A news report in the Associated Press after the beheadings of two Americans in the Middle East in 2004 quotes an immigration lawyer, Sohail Mohammed, ‘‘Since 9/11, every time there is an incident overseas attributed to Muslims or Arabs, we go on orange alert ourselves. . . . There are indi-viduals here who are off the wall, who think that every woman who wears a hijab or every man named Mohammed is out to blow things up.’’ (Parry 2004).

Table 4

Difference-in-differences Estimates of the Effect of September 11thon Earnings of Arab and Muslim Men, by period since

September 11th: CPS September 1998- August 2001; October 2001-September 2004

Log (Real Hourly Earnings)

1-12 months after 9/11

(1)

13 to 24 months after 9/11

(2)

25 to 36 months after 9/11

(3)

DD (Target-comparison group I) 20.094* 20.104 20.100

(0.052) (0.079) (0.072)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 20.091* 20.092 20.085

(0.053) (0.078) (0.072)

Log (Real Weekly Earnings)

DD (Target-comparison group I) 20.109* 20.095 20.112

(0.060) (0.091) (0.087)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 20.114* 20.096 20.118

(0.063) (0.095) (0.093)

Note: Coefficients in each row are estimates based on Model 2 for these outcomes in Table 2, in which the effect of September 11this allowed to differ by years since the

event. See Table 1 for sample definition and sample sizes. Robust standard errors clustered around state and target (or comparison) group are in parentheses. *0.05<p¼<0.1, ** 0.01<p¼<0.05, ***p¼<0.01.

294

The

Journal

of

Human

September 11thover time. The decrease in wages and weekly earnings in the three years post-September 11thare all of the same approximate magnitude.

To further assess the timing of the effects of September 11thon wages and weekly earnings, we obtained estimates using different pre- and post-September 11thperiods.

To this point, we have used a three-year pre- and post-September 11thperiod span-ning September 1998 to August 2004. We now try four alternatives: a two-year pre- and post-September 11th period, a four-year pre- and a two-year post period, a four-year pre- and a three-year post period and a four-year pre- and post period. Estimates from these models are presented in Table 5 along with the original esti-mates that use a three-year window.

As can be seen, estimates obtained using a two-year window are very similar to those that use a three-year window, although they are slightly larger; September 11this associated with an 11 to 14 percent decline in wages and weekly earnings.

Estimates using a four-year pre- and two-year post period were similar to estimates obtained using a three-year window. Estimates obtained using a four-year pre- and three-year post-September 11thperiod are somewhat smaller—a 7-9 percent decline in wage and earnings. In contrast, estimates obtained using a four-year pre- and post-September 11thwindow indicate a much smaller and statistically insignificant, neg-ative effect. This result, as are all of the wage and earnings results, is being driven by the experiences of the target group. We compute the ‘‘first difference’’ estimates of the effect of September 11thfor each period by using just the target or just the com-parison group and find that pre- to post-September 11thchanges in wages for the

tar-get group are negative and statistically significant in the period from 1997 to 2003.20 However, expanding the period past 2003, particularly to 2005, the pre- to post-September 11th change in wages and weekly earnings are smaller (less negative). The change is driven primarily by the addition of 2005. Estimates of the pre- and post-September 11th changes in wages and earnings for the comparison group are small and positive for all periods of analysis.

It is important to note that the sensitivity of the estimates to the period of analysis is not evidence of an invalid research design. As we have already demonstrated, trends in wages and weekly earnings in the four-year pre-September 11th period (September 1997 to August 2001) are the same for the target and comparison group of men condi-tional on other measured covariates. Moreover, if we use the four-year pre-September 11thperiod and either a two- or three-year post-September 11thperiod, the negative wage and weekly earnings effects remain more or less the same. So the absence of an effect of September 11thobserved for the 1997 to 2005 period reflects a change in post-September 11thwages and weekly earnings of Arabs and Muslims that occurs in 2005 (October 2004 to September 2005). During this period, wages of Arabs and Muslims are significantly higher than they were in other post-September 11thperiods. Our reading of this evidence is that September 11thhad a significant adverse effect on Arab and Muslim wages and weekly earnings, but that there is some evidence that these negative effects were beginning to diminish as time since September 11th pro-gressed. Evidence for short-term adverse effects is strong, as results were robust to a variety of model specifications and are supported by validation tests of the underly-ing research design. However, an alternative explanation that we cannot rule out is

20. These estimates can be obtained from the authors on request.

Table 5

Difference-in-differences Estimates of the Effect of September 11thon Earnings of Arab and Muslim Men

Log (Real Hourly Earnings)

Period of analysis Sept 1999–

Sept 2003 (1)

Sept 1998– Sept 2004

(2)

Sept 1997– Sept 2003

(3)

Sept 1997– Sept 2004

(4)

Sept 1997– Sept 2005

(5)

DD (Target-comparison group I) 20.128*** 20.095* 20.090* 20.073 20.014

(0.043) (0.049) (0.042) (0.046) (0.042)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 20.113** 20.092* 20.079* 20.066 20.053

(0.048) (0.051) (0.042) (0.045) (0.049)

Log (Real Weekly Earnings)

DD (Target-comparison group I) 20.143* 20.110* 20.112** 20.087* 20.010

(0.071) (0.057) (0.049) (0.046) (0.049)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 20.124* 20.114* 20.109** 20.089* 20.078

(0.072) (0.059) (0.051) (0.048) (0.052)

Note: Figures in each cell are from separate regressions based on Model 2 for these outcomes in Table 2. See Table 1 for sample definition and sample sizes. Robust standard errors clustered around state and target (or comparison) group are in parentheses. *0.05<p¼<0.1, ** 0.01<p¼<0.05, ***p¼<0.01.

296

The

Journal

of

Human

the possibility that the attenuation of estimates in 2005 is due to changes in the com-position of the target group. We find some evidence of this. For example, the propor-tion of men from Pakistan, Egypt, and Turkey was 30 percent in the 12 months before September 11th and this proportion fell to 23 percent the period October

2004 to September 2005. We also find that the share of men from Iraq and Afghani-stan rose from 6 to 9 percent during this period. While we control for country of birth and other observable characteristics, changes in unobserved characteristics of the sample may be the cause of the diminished effects.

E. Do Effects Differ by Nativity, Education, or Residential Location?

To this point, the results of our analysis provide evidence that September 11th ad-versely affected the wages and weekly earnings of Arab and Muslim men. The ques-tion remains, did this affect some Arabs and Muslims more than others? To answer this question, we investigated whether the effect of September 11thdiffered by char-acteristics that are arguably correlated with stronger ethnic identity (that is, less as-similation) and thus potentially greater prejudice: whether person is foreign-born (first generation); whether the person is highly educated; and whether the person lives in a state with relatively high Arab and Muslim density.

To see whether the foreign-born among the target group were more adversely af-fected by September 11th, we reestimated Model 2 of Table 2 after restricting the sam-ple to the foreign-born in the target group and Comparison Group I. The results of this analysis (not presented) were virtually the same as those reported in Table 2, which is not surprising since 86 percent of our target group consists of first-generation men.21 Next, we examined the effects of September 11thon men with and without a BA degree and on men who lived in states with above- and below-median Arab and Muslim den-sity. The results of these analyses (not presented) also were very similar to those pre-sented in Table 2; September 11thdid not have a statistically different effect on men with a BA degree versus those without a BA. Finally, our analysis of whether the target group living in states with a relatively high density of Arabs and Muslims were affected differently by the events of September 11thfrom those living in low-density states also

found no statistically different effects between the two groups (results not presented). However, some of the point estimates were quite different across groups.

Public resentment toward Arabs and Muslims after September 11thmay not have been uniform across localities, as reported hate crime was greater in some places than others. If incidents of hate crime are an indicator of public sentiment toward Arabs and Muslims, we should find more evidence of labor-market discrimination (that is, larger negative effects) in states with more hate crime incidents. We inves-tigated this using an index of the degree of intolerance as measured by the incidence of FBI reported hate crimes motivated by religious, ethnicity, or national origin bias. We used two rates of incidence: number of hate crimes per Arab population in a state, and the number of hate crimes per (total) population in a state. We divided states into two groups—those with above or below median incidence rates.

Table 6 presents the results of the analysis. The results are striking. In states with lower rates of hate crime and presumably less prejudice, September 11this associated

21. All estimates not presented are available upon request form the authors.

Table 6

Difference-in-differences Estimates of the Effect of September 11thon Earnings of Arab and Muslim Men by Degree of Intolerance in State of Residence: CPS September 1998- August 2001; October 2001-September 2004

Log (Real Hourly Earnings)

Intolerance based on FBI hate crime incidents per Arab population

Intolerance based on FBI hate crime incidents per US population

High-intolerance* Sept 11*treat (1)

Low-intolerance* Sept11*treat (2)

High-intolerance* Sept 11*treat (3)

Low-intolerance* Sept11*treat (4)

DD (Target-comparison group I) 20.111** 20.071 20.115** 20.061

(0.051) (0.059) (0.046) (0.066)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 20.109** 20.069 20.114** 20.059

(0.052) (0.063) (0.047) (0.069)

Log (Real Weekly Earnings)

DD (Target-comparison group I) 20.131** 20.082 20.132** 20.072

(0.054) (0.079) (0.050) (0.076)

DD (Target-comparison group II) 20.137** 20.084 20.141*** 20.074

(0.057) (0.083) (0.052) (0.079)

Notes: Figures in each row of Columns 1–2 and 3–4 are from separate regressions based on Model 2 for these outcomes in Table 2. High-intolerance states are those with more than median FBI hate crime incidents motivated by religious, ethnic, or national-origin bias per Arab or U.S. population (as listed in column subheadings), and low-intolerance states are those with less than median hate crime. Robust standard errors clustered around state and target (or comparison) group are in parentheses. *0.05<p¼<0.1, ** 0.01<p¼<0.05, ***p¼<0.01.

298

The

Journal

of

Human

with smaller adverse effects on wages and earnings.22While we cannot reject the equality of effects across the two groups of states, the point estimates are markedly different. In relatively intolerant states, September 11this associated with an 11 per-cent decrease in the wages of Arab and Muslim men whereas in relatively tolerant states, September 11this associated with only a 6-9 percent decline.

F. Possible Channels of Discrimination

To investigate whether September 11thaffected occupational choice, for example by forcing more Arab and Muslim men to become self-employed or by decreasing the demand for Arab and Muslim men in retail jobs where there is greater customer contact, we examined whether September 11thaffected the probability of being self-employed or the probability of working in retail. Estimated effects were small in mag-nitude and not statistically significant, providing little evidence that the probability of being self-employed or of working in retail sector was affected by September 11th.23 In Table 2, we found evidence that changes in occupation and industry were chan-nels through which the September 11theffect operated. To examine this issue further, we calculated the average wage in each three-digit industry and three-digit occupa-tion using the CPS-ORG from 1997 to 2002.24Then, using the March CPS in 2001 (pre-September 11th) and 2002 (post-September 11th), we examined whether Arab and Muslim men were more likely to report a change to a lower (higher) wage in-dustry or occupation in the pre- versus post-September 11th period than men in the two comparison groups. A change in industry or occupation occurred if the per-son reported that their current industry or occupation was different from the industry or occupation on the longest job held last year. Estimates were obtained using a mul-tinomial logit regression model with three choices: whether the individual moved to a lower-wage industry, whether the individual moved to a higher wage industry and nonmovers or those who moved within the same wage industry. We combined the category of movers within the same wage industry (occupation) with nonmovers be-cause less than 0.1 percent of sample moved within same wage occupation or indus-try. We apply the difference-in-differences research design and results are presented in Table 7. Here, we find strong evidence that September 11th is associated with a significant increase in movement of Arab and Muslim men from higher-to-lower paying industries. Similar effects were not found for occupation. This pro-vides further evidence that the mechanism by which greater prejudice resulted in lower wages was changes in industry of employment.

G. Residential Mobility

We also investigated whether September 11th altered the internal migration of Arabs and Muslims. As discussed earlier in the paper, theoretical considerations

22. As a specification check, we repeat the hate crime analysis by merging January to June CPS-ORG in yeartwith average hate-crime data in yeart21 andtand July-December CPS-ORG in yeartwith average

hate-crime in yeartandt+ 1. The estimated effects were similar to the analysis in which hate crime data is merged by state and year. To conserve space we have opted not to present those results.

23. These estimates can be obtained from the authors on request.

24. The CPS changed industry and occupation codes after 2002. Since our objective here is to obtain wages for three-digit industries and occupations based on codes for 2001 and 2002, we do not use the post-2002 data to compute industry- and occupation-specific wages.

Table 7

DD (Target-comparison group I)

— — 0.073*** 0.006 — — 0.006 20.003

(0.028) (0.029) (0.004) (0.024)

DD (Target-comparison group II)

— — 0.087*** 0.010 — — 0.009 0.002

(0.013) (0.034) (0.014) (0.036)

Note: Figures in each cell of Columns 1–2 and 5–6 are unadjusted means. Figures in Columns 3–4 and Columns 7–8 are marginal effects from multinomial logit models with three categories, two of which are listed as column headings; the third, the reference category, consists of nonmovers or those who moved in the same wage occupation/industry. (The proportion that moved within the same wage occupation or industry is less than 0.1 percent.) Each row in Columns 3–4 and Columns 7–8 is from a separate regression that controls for age, education, race, marital status, whether respondent has children younger than age 18, state unemployment rate, per capita income, number of years lived in the United States, citizenship status, whether foreign-born, and state of residence. State fixed effects, unemployment rate and per capita income effects are allowed to differ for the target and comparison groups; all other effects are restricted to be the same for the two groups. Robust standard errors clustered around state and target (or comparison) group are in parentheses. See notes in Table 1 for the definitions of target and comparison groups. * 0.05<p¼<0.1, ** 0.01<p¼<0.05, ***p¼<0.01.

Kaushal,

Kaestner

,

and

Reimers

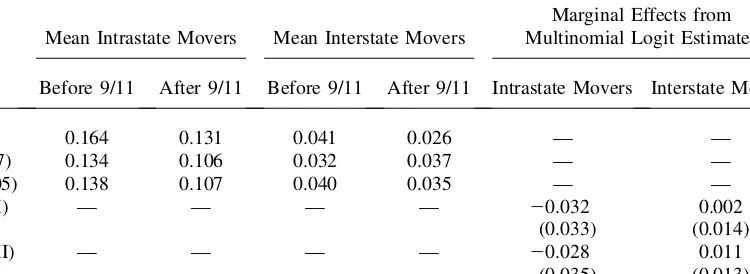

are inconclusive, suggesting that September 11thmay have either increased or de-creased migration. We conducted two analyses to investigate how September 11th af-fected the internal migration of Arabs and Muslims. Like our other analyses, these are restricted to persons in 20 states where 85 percent of the target group lives. First, we examine whether a person moved at all: to a new state; within state; or did not move. Table 8 has the results of this analysis. The first four columns of that table have the unadjusted means of intra and interstate moves of the target and comparison groups before and after September 11th. These numbers reveal three important aspects of their residential mobility. First, prior to September 11th, intrastate residential mobility was greater among the target group than among the comparison groups. Second, there was a distinct decline after September 11thin the proportion of the target group that made a residential move of either type. And third, there are similar changes after Sep-tember 11thin the proportion of the comparison groups making intrastate moves, but

interstate moves among Comparison Group I increased in the post-September 11th period, while interstate moves among Comparison Group II declined slightly.

Columns 5 and 6 of Table 8 contain the results of the multivariate analyses. Esti-mates in each row in these columns are from a separate regression that controls for age, education, race, marital status, gender, whether a respondent has children less than 18, number of years lived in the United States, citizenship status, whether foreign-born, state of residence last year, unemployment rate, and per capita income in the state of residence last year. The effects of the latter three variables are allowed to differ between the target and comparison groups in the difference-in-differences analysis.

As mentioned above, each dependent variable has three categories. Two of them (intrastate move and interstate move) are listed as column subheadings and the third (nonmove) is the reference category. Estimates are obtained using a multinomial logit model. Marginal effects of the probability of being in a given category are reported along with the corresponding standard errors (adjusted for heteroskedasti-city, clustered on state and target group).

The estimates suggest that September 11threduced intrastate moves by Arabs and

Muslims. Difference-in-differences estimates suggest that the intrastate moves of Arabs and Muslims declined by approximately three percentage points, or 20 percent rel-ative to the pre-September 11thmean, but these estimates are not statistically significant. We also used the index of hate crime described earlier to infer whether a person moved to avoid discrimination. In that analysis, we examined moves from high- to low-intolerance states, low- to high-intolerance states, and noninterstate moves (in-cluding intrastate moves). Estimates from this analysis (not presented) suggest that September 11th is not associated with any strategic interstate migration to avoid discrimination.

In sum, these results provide some evidence that the September 11th terrorists’ attacks reduced intrastate migration of Arabs and Muslims. This is consistent with the hypothesis that fears engendered by September 11th(or actual experience of dis-crimination) restricted the internal mobility of Arabs and Muslims living in the United States And the fact that intrastate moves were affected suggests that Septem-ber 11th affected relatively local moves that may reflect the security of ethnic enclaves. However, this result also is consistent with a proportional fall in wages for Arabs and Muslims across locations, which, given fixed costs of moving, would reduce migration.

Table 8

Geographic Relocation of Men: March CPS: 1999-2004

Mean Intrastate Movers Mean Interstate Movers

Marginal Effects from Multinomial Logit Estimates

Before 9/11 After 9/11 Before 9/11 After 9/11 Intrastate Movers Interstate Movers

Target (N¼1,782) 0.164 0.131 0.041 0.026 — —

Comparison group I (N¼16,717) 0.134 0.106 0.032 0.037 — —

Comparison group II (N¼26,705) 0.138 0.107 0.040 0.035 — —

DD (Target-comparison group I) — — — — 20.032 0.002

(0.033) (0.014)

DD (Target-comparison group II) — — — — 20.028 0.011

(0.035) (0.013)

Notes: Figures in each cell of Columns 1-4 are unadjusted means. Figures in Columns 5 and 6 are marginal effects from multinomial logit models with three categories, two of which are listed as column headings; the third, the reference category, consists of nonmovers. Each row in Columns 5 and 6 is from a separate regression. Each regression controls for age, education, race, marital status, whether respondent has children younger than 18, unemployment rate, and per capita income in the state of residence last year, number of years lived in the United States, citizenship status, whether foreign-born, and state of residence last year. Robust standard errors clustered around state and target (or comparison) group are in parentheses. In the regression analysis, the effects of unemployment rate, per capita income and state fixed effects are allowed to differ between the target and comparison groups; all the other effects are restricted to be the same for the two groups. See notes in Table 1 for the definitions of target and comparison groups. * 0.05<p¼<0.1, ** 0.01<p¼<0.05, ***p¼<0.01.

Kaushal,

Kaestner

,

and

Reimers