Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Benefits and Problems With Student Teams:

Suggestions for Improving Team Projects

Randall S. Hansen

To cite this article: Randall S. Hansen (2006) Benefits and Problems With Student Teams: Suggestions for Improving Team Projects, Journal of Education for Business, 82:1, 11-19, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.82.1.11-19

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.82.1.11-19

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1432

View related articles

ABSTRACT. Business school faculty

have been placing students into teams for

group projects for many years, with mixed

results. Obvious benefits accrue in using

teams, but so do numerous problems. One

of the main issues is that many business

faculty often place students in teams with

little or no guidance on how teams properly

function. In this article, the author

synthe-sizes a detailed review of the literature on

teams and teamwork, examining the

bene-fits and problems of using student teams

and then suggests processes business

facul-ty can put in place to maximize the benefits

of group projects, while minimizing the

problems. A preliminary study of student

perceptions of team projects is also

includ-ed in this review.

Key words: business education, group

projects, teams

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

Benefits and Problems With Student Teams:

Suggestions for Improving Team Projects

RANDALL S. HANSEN STETSON UNIVERSITY DELAND, FLORIDA

eams and teamwork have been long used by business and, over the years, much has been written on the subject specifically examining the development and use of teams in college to help prepare students to be produc-tive members of work teams. My pur-pose in this article is to present a com-prehensive review and synthesis of the literature involving teamwork and stu-dent teams from within all aspects of the business disciplines and beyond, bring-ing together a meta-analysis of the extant literature examining the benefits and problems with student team pro-jects, then suggesting improvements in the quality of student teamwork to fac-ulty considering using team projects in their classes.

Work Teams and Teamwork

Workers within organizations have traditionally worked in teams for some projects, but the increase of work teams and the importance of teamwork skills have increased dramatically over the last two decades (e.g., Applebaum & Blatt, 1994; Taninecz, 1997). Several studies indicate that more than 80% of organizations employ multiple types of workplace teams (Cohen & Bailey, 1997; Sundstrom, 1999).

According to Tarricone and Luca (2002), collaborating in teams requires much more than traditional business

skills. They noted that “skills such as problem solving, communication, col-laboration, interpersonal skills, social skills, and time management are actively being targeted by prospective employers as essential requirements for employa-bility. Employers consistently mention collaboration and teamwork as being a critical skill, essential in almost all working environments” (Tarricone & Luca, p. 54).

Hernandez (2002) stated that employ-ers seek employees who can analyze, evaluate, and find solutions to prob-lems—higher level thinking that comes from active and cooperative learning. He added, “employers also need employees who know how to work effectively with others. Self-managed teams are performing increased amounts of work in many organizations today” (p. 74).

The ability to manage a team is one of the skills that employers covet in potential managers (Ashraf, 2004; Chen, Donahue, & Klimoski, 2004) and seek in new business school graduates (McCorkle et al., 1999; Tarricone & Luca, 2002; Thacker & Yost, 2002). Anecdotal data, as presented in Appen-dix A, show the importance that recent graduates apply to teamwork. The com-ments presented here all stress the amount of teamwork found in the work-place, its value to college students and graduates, and the importance of

learn-T

ing these teamwork skills while in col-lege (Quintessential Careers, 2004).

Furthermore, evidence supports the theory that decision making is improved when teamwork is employed (Bamber, Watson, & Hill, 1996; Hackman, 1990). Teamwork skills (learning experiences in group dynamics) are even a learning standard that Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (2005) expects its member institutions to impart to their students as part of accreditation.

Student Teams and Group Projects

Because of the increased demand for teamwork in business, employers turned to business schools to incorporate team-building exercises and group projects into the curriculum, with the idea that students working in teams would learn teamwork, problem-solving, communi-cations, leadership, and other key skills (Alexander & Stone, 1997; Ashraf, 2004; Bolton, 1999; Kunkel & Shafer, 1997). Hernandez (2002) describes team learning as the creation of cooper-ative structures that promote active and higher-level learning or thinking.

The literature provides evidence of a dramatic increase in the use of teams throughout the business curriculum (Batra, Walvoord, & Krishman, 1997; Deeter-Schmelz & Ramsey, 1998; Her-nandez, 2002; Robbins, 1994), but as Barker and Franzak (1997) stated, “placing students into groups for class projects is not the same as developing teams, even when the term ‘team’ is applied” (p. 304).

Many faculty assume that student team projects of any kind provide a real-istic experience in terms of team dynam-ics, cooperation, leadership, group deci-sion making, and communications while also allowing students to accomplish larger projects than could be completed individually and enhancing each team member’s discipline-specific knowledge (McCorkle et al., 1999; McKinney & Graham-Buxton, 1993; Rau & Heyl, 1990).

However, research shows, that, in many classes, students are simply placed into team projects with no preparation,

resulting in students being ineffectively prepared for work teams (Bacon, Stew-art, & Silver, 1999; Bolton, 1999; Ettington & Camp, 2002; Rotfeld, 1998), as well as in unclear goals, mis-management, conflict, and unequal par-ticipation (Cox & Bobrowski, 2000; McCorkle et al., 1999; McKendall, 2000; Rau & Heyl, 1990). It is clear that although group work is an important ele-ment of business-school curricula, sim-ply placing students in a team or group and telling them to be a team does not, in itself, result in higher achievement (Johnson & Johnson, 1990).

Despite these problems, several researchers (McCorkle et al., 1999; McKinney & Graham-Buxton, 1993) have reported that students generally respond positively to group work and that team assignments can be useful in the acquisition of team skills. Further-more, student attitudes about teamwork have been shown to be positively related to teamwork effectiveness (Gregorich, Helmreich, & Wilhelm, 1990; Stout, Salas, & Fowlkes, 1997). In addition, many benefits accrue for students when they work in teams. Numerous research-ers have shown that the learning-by-doing approach of group projects results in active learning and far greater compre-hension and retention of information, higher levels of student motivation and achievement, development of critical reasoning skills, improved communica-tions skills, and stronger interpersonal and social skills than is found with tradi-tional lecture-style teaching methods (Ashraf, 2004; Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991). When student dissatisfac-tion and frustradissatisfac-tion arise, Feichtner and Davis (1984) reported that it was caused by students’ self-perceived inability to manage group process issues, such as logistics, workload, motivation, and group dynamics.

Specific problems that students face in group projects range from a lack of leadership, scheduling conflicts, lack of team development, free-riding or social loafing, and students who prefer to work alone.

Appendix B lists the key benefits and problems associated with using team pro-jects that have been covered in the extant literature along with the specific citations related to each benefit and problem.

The Team Development Issue

Rotfeld (1998) stated that “Group projects are many but few faculty assigning them give attention to improving student speaking, writing, or group interactions. The classes do not teach these things except by contagion and therein lies the real problem” (p. 6). Furthermore, Verderber and Serey (1996) stated that the faculty who assign group projects “need to assume addi-tional responsibilities if effective stu-dent learning is to occur” (p. 23). Final-ly, Chen, Donahue, and Klimoski (2004) added that, “although some uni-versity curricula focus on developing some level of teamwork knowledge, teamwork competencies and skills are rarely developed” (p. 28).

Therefore, it is fairly clear from the literature that business faculty have heeded the call from employers, altering their courses to emphasize group and team work. What is also clear, though, is that group assignments are often made with little or no preparation to help the students function in the groups or teams.

This fundamental disconnect between the use of teams and teamwork prepara-tion is a significant problem. It is clear that something needs to change, and Deeter-Schmelz, Kennedy, and Ramsey (2002) proposed that it is the responsi-bility of business schools to train stu-dents on teamwork.

Suggestions for Improving Team Projects

Several authors have published arti-cles on student team building (Clinebell & Stecher, 2003; McKendall, 2000; Page & Donelan, 2003), managing teamwork in the classroom (Siciliano, 1999; Verderber & Serey, 1996), and the importance and value of having teams that work well together (Deeter-Schmelz, Kennedy, & Ramsey, 2002; Duemer et al., 2004). Newstrom and Scannell (1998) stated: “High-perform-ing teams usually exhibit an overall team purpose, mutual accountability, collective work products, shared leader-ship roles, high cohesiveness, collabora-tion in deciding task assignments and procedures, and collective assessment of their own success” (p. xi).

On the basis of a review of the litera-ture, I developed 10 suggestions for fac-ulty who seek to improve the perfor-mance of student teams as well as the satisfaction of the students in those teams.

The 10 suggestions, described in more detail in the following section, include: (a) emphasizing the importance or relevance of teamwork, (b) teaching teamwork skills, (c) conducting team building exercises, (d) determining the best method of team formation, (e) assigning a reasonable workload and clear goals, (f) requiring groups to have specific or assigned roles, (g) providing some class time for team meetings, (h) requesting multiple feedback points for monitoring typical team problems, (i) requiring individuals to keep a personal contributions file, and (j) using detailed peer evaluations as part of grading.

Emphasizing the Importance and Relevance of Teams and Teamwork

Researchers have found that attitudes toward the value of teamwork and rele-vance to real-world situations are posi-tively related to attitudes toward team-work and team effectiveness (Gregorich, Helmreich, & Wilhelm, 1990; Pfaff & Huddleston, 2003; Stout et al., 1997). When introducing student team projects, faculty should emphasize the impor-tance and value of learning teamwork and leadership skills. Students should be informed that teams, and more impor-tant, the ability to work in teams and to lead teams, has become an important skill to master and one that employers seek of newly graduated business stu-dents. Instructors could have students read one of these or perhaps even invite an employer or alumnus to class to relate stories of the importance of teams in business.

Teaching Team Development and Teamwork Skills

Perhaps one of the unrealistic aspects of using groups and teams in the class-room is the process of team develop-ment, and the time it takes for teams to work through issues until they are at the point at which they can fully function. Certainly one of the seminal works on group development is Tuckman’s (1965) model that theorizes that a group moves

through a number of stages. In the form-ing stage, members of a group have a desire for acceptance and attempt to avoid controversy, while beginning ini-tial examination at the task at hand. In the storming stage, conflict emerges over team roles, expectations, and lead-ership. In the norming stage, a group structure and cohesion within the group begin to develop, roles become clearer, and trust emerges. In the performing stage, the group is functioning at peak performance, and members have strong trust and a high commitment to the group (Tuckman; Tuckman & Jensen, 1977). Several authors have focused on the importance of trust in effective team development (Huff, Cooper, & Jones, 2002; Johnson & Johnson, 1975; Yeatts & Hyten, 1998). Students should learn about the stages of team development and the importance of trust and commu-nication in teamwork.

Conducting Team-Building Exercises for Cohesive Groups

Chen, Lawson, and Gordon (1996) discussed the importance of team mem-bers’ feeling that they are deeply involved in a cohesive group and that cohesion plays a critical role in effective teamwork. One method of building cohe-sion is through team-building exercises (Deeter-Schmelz et al., 2002). Team-building is about integrating individuals into a unified effort (Newstrom & Scan-nell, 1998). Team-building exercises and games can focus on improving commu-nications, sharing expectations, clarify-ing goals, formulatclarify-ing operatclarify-ing guide-lines, and solving problems (Barker & Franzak, 1997), as well as on developing team identity, morale, trust, or adaptabil-ity and flexibiladaptabil-ity (Newstrom & Scan-nell). Team-building exercises include games that break down barriers among members (self-disclosure); create team identity through the development of team names, logos, mottos, songs, mission or vision statements; and facilitate group interaction through some task.

Determining Method of Team Formation

Two main team selection methods are commonly used: professor-selected and student-selected. Limited evidence

sug-gests that professor-selected groups are seldom used possibly because of the ception that student-selected groups per-form better than do professor-selected teams (Connerley & Mael, 2001). How-ever, Muller (1989) stated that student preferences are not necessarily the most important criterion for successful group work, whereas Koppenhaver and Shrad-er (2003) suggested that instructor-assigned teams lead to more stability in membership, and that stability enhances each team’s ability to perform effective-ly. Contrary to earlier researchers, Her-nandez (2002) stated that student teams should be formed by the instructor, and that students are more likely to have a positive learning experience when groups are selected by the professor. The worst method of team selection is ran-dom selection, where students often choose people from their social network of friends (Levine & Moreland, 1990). Professor-selected teams also more closely match the workplace, in which supervisors place workers in teams rather than allowing them to self-select.

Assigning a Reasonable Workload and Establishing Clear Goals

The team project should be meaning-ful and relevant (McKendall, 2000), and present a manageable workload for the teams (Feichtner & Davis, 1984; Pfaff & Huddleston 2003). Although one of the reasons for using teams is for when pro-jects are deemed too large for individual assignment (Allen, Morgan, Moore, & Snow, 1987; Freeman, 1996; Latting & Raffoul, 1991; Williams et al., 1991), students who perceive they have been assigned too much work may develop negative attitudes toward teamwork (Pfaff & Huddleston, 2003). One sugges-tion is to use teams for larger, semester-long, subject-relevant (e.g., the develop-ment of a marketing plan in a strategic marketing class) projects with clearly defined parameters. It is critical for the faculty member to be specific about the parameters and expected outcomes of the team project.

Requiring Team Members to Have Specific and Assigned Roles

Page and Donelan (2003) discussed the value of teaching students the

icance of different group roles, as well as motivating them to take responsibility for those team roles. They suggested one method of helping students understand these varying roles was by having them complete a role-assignment exercise, in which members of a team take turns as team leader, gatekeeper, recorder, time-keeper, and social or emotional leader. Having specific roles and expectations may also help reduce one of the major problems of team assignments which is free-riding or social loafing. Roles can be assigned by the professor (e.g., when the professor chooses team leaders), or, team roles can develop naturally through team-building exercises and the natural progression of team formation. It is also possible for teams to rotate roles and authority. For example, Erez, Lepine, and Elms (2002) found that teams that rotated leadership among members had higher levels of cooperation and perfor-mance. Regardless of the method used, the key is having teams clearly identify roles for each member, whether they rotate or not.

Providing Some Class Time for Team Meetings

Most big, semester-long projects take considerable amounts of time to manage and although students are expected to meet extensively outside of class for most group projects, McK-endall (2000) stressed the importance of giving teams time to meet during class. Besides alleviating some time pressures, having student teams meet in class gives the instructor a chance to observe team behaviors. Furthermore, both Feichtner and Davis (1984) and Pfaff and Huddleston (2003) found that providing more class time devoted to working on a team project yields more positive attitudes toward teamwork. Feichtner and Davis found that stu-dents who reported having the best team experiences had been allotted 36% of class time to work in groups. Pfaff and Huddleston stress, the impor-tance of providing class time at the beginning of projects, during team for-mation, but also commented on the reality of sacrificing class time for teamwork, even when students prefer more of it.

Requesting Interim Reports and Other Feedback Points

Several researchers (Brooks & Ammons, 2003; McKendall, 2000) have suggested the importance of having multiple points of feedback about group performance, more so for team mem-bers than for the faculty. By completing interim reports, all members of the team can see their contributions (or lack thereof) to date. Verderber and Serey (1996) suggested requiring teams to submit written progress reports to the professor at three points during the course of the project, each with a spe-cific list of goals and achievements. The first report deals more with team man-agement and planning, the second (usu-ally around midterm) examines progress toward goals and forces teams to make adjustments in order to complete the project successfully, and the third (about two weeks before the completion date) deals with managing the final stages of the process. Feichtner and Davis (1992) suggested that providing feedback to students on their perfor-mance within the team at multiple points allows lagging students the chance to improve their contributions. One solution to the lack of feedback problem is requiring team members to submit a midterm peer evaluation, which can then be used not only for assessing progress, but to help the team make corrections before final peer eval-uations are completed.

Requiring Individual Team Members to Keep Personal Contributions File

Fostering individual accountability is critical because it simplifies the man-agement of team processes and can clearly differentiate performers from nonperformers (Page & Donelan, 2003) as well as help mitigate the prob-lem of free riding (Joyce, 1999). Stu-dent contribution files can be useful when issues arise about individual con-tributions and help with providing more detail in peer evaluations. Stu-dents can be requested to record their contributions to the team as they hap-pen, on a weekly basis, or submitted with the team interim reports. From a practical standpoint, getting students into the habit of documenting their

work and accomplishments will be extremely beneficial for them in their careers, where documenting accom-plishments is critical to success in obtaining promotions and new jobs.

Using Detailed Peer Evaluations as a Part of Grading Team Effort

The use of peer evaluations also helps with the free-riding problem by serving as an accountability tool with the added benefit of providing the instructor with useful information for the evaluation process (Johnson & Smith, 1997). McK-endall (2000) suggests a 20-item instru-ment that team members complete about themselves and all members of the team. Then, each team meets and consolidates the individual rankings into one team rating for each member. Besides using peer evaluations to evaluate each mem-ber’s contribution to the team, Verderber and Serey (1996) also allow one or two members of each team to receive leader-ship bonus points based on their contri-butions to the team (as decided by peer consensus). Furthermore, Pfaff and Huddleston (2003) found the use of peer evaluations yields a more positive atti-tude toward teamwork because such feedback methods allow students to feel they are more in control of the result of their efforts. Students react more posi-tively and attain higher levels of perfor-mance not only when peer evaluations are used (Erez et al., 2002), but also when evaluations contribute to the course grade (Feichtner & Davis, 1984). Several researchers (Clinebell & Stech-er, 2003; Paswan & Gollakota, 2004; Siciliano, 1999) have published peer or team evaluation forms that faculty can incorporate.

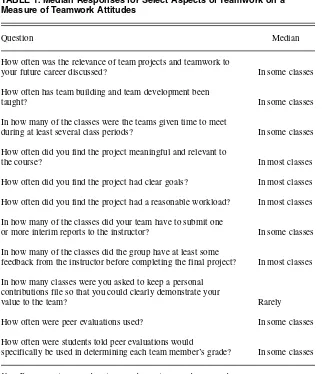

A Measure of Students’ Attitudes Toward Teamwork

This section provides some prelimi-nary research into whether business fac-ulty have heeded the call to use student teams, how faculty members approach teamwork, and student perceptions on teams. The sample consisted of students in a senior-level marketing class, com-posed mostly of marketing majors, but also finance, management, and general business majors. A total of 34 students completed the assessment.

As can be seen in Table 1, college seniors participated in an average of 5–6 teams with the two most common meth-ods for assigning students to teams being: professors randomly placing stu-dents in teams and stustu-dents self-selecting based on personal factors. Student selec-tion is not only the most common, but is also the most frequently used method. The results show, that overall, students are aware of the relevance of teamwork and at least somewhat satisfied with stu-dent team projects.

The results in some of the areas that were identified for improvement are mixed. The teaching of team building or the requirement to conduct team-build-ing exercises was used in only some classes. Even with this modest approach to team development, students found team projects meaningful and relevant for the most part, with a reasonable workload and clear goals. Although

peer evaluations were used in at least some classes, having each team member keep a personal contributions file was rarely used. Finally, while students had to submit one or more interim reports to the instructor in only some classes, the students received some sort of feedback from the instructor before completing the final project in more classes.

Finally, students were asked an open-ended question regarding key character-istics of their most satisfying group pro-jects. Their responses, shown in Appendix C, are easily organized around several of the key elements of successful teams identified earlier in this article, including: cooperation, leadership, relevancy, clear goals, team roles, and interim reports.

DISCUSSION

It is clear that faculty have gotten at least half the message about teams.

Fac-ulty have heeded the call from employ-ers to incorporate more team projects in their classes. For the foreseeable future, the use of student teams seems likely to continue, both as a pedagogical tool and in response to the demands of outside stakeholders regarding the need of busi-ness school graduates to have teamwork and leadership skills and experience. However, it appears that the majority of faculty who place students into teams do nothing more than that, either because of time constraints or not being overly familiar (or comfortable) with the team-work and team-building literature.

My purpose in this article was to review the large body of research on teams and teamwork, summarize the value of teams and team skills, illustrate the problem of using teams for the sake of having group projects, provide an overview of the benefits and problems with student teams, offer some sugges-tions for improving team projects, and provide some preliminary results from a pilot study on business students’ percep-tions of teamwork.

The detailed literature review in this article lays an important foundation for planning future research. The results described in this article concerning student responses to teamwork confirm that while teams are being used in many business classes, there is much improvement that can be done based on the 10 suggestions for improving team projects. That said, this study was extremely limited in size and scope. What is needed is a much larger sam-ple across several institutions. More specific research into the value of each of the 10 suggestions also could be developed and tested. The team-build-ing and teamwork area is a rich area for scholars and should continue to be investigated.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Randall S. Hansen, School of Business Administration, Stetson University, 421 N. Woodland Blvd., Unit 8398, DeLand, FL 32723.

E–mail: rhansen@stetson.edu

REFERENCES

Alexander, M. W., & Stone, S. F. (1997). Student perceptions of teamwork in the classroom: An analysis by gender. Business Education Forum, 51(3), 7–10.

TABLE 1. Median Responses for Select Aspects of Teamwork on a Measure of Teamwork Attitudes

Question Median

How often was the relevance of team projects and teamwork to

your future career discussed? In some classes

How often has team building and team development been

taught? In some classes

In how many of the classes were the teams given time to meet

during at least several class periods? In some classes

How often did you find the project meaningful and relevant to

the course? In most classes

How often did you find the project had clear goals? In most classes

How often did you find the project had a reasonable workload? In most classes

In how many of the classes did your team have to submit one

or more interim reports to the instructor? In some classes

In how many of the classes did the group have at least some

feedback from the instructor before completing the final project? In most classes

In how many classes were you asked to keep a personal contributions file so that you could clearly demonstrate your

value to the team? Rarely

How often were peer evaluations used? In some classes

How often were students told peer evaluations would

specifically be used in determining each team member’s grade? In some classes

Note. Responses:in every class, in most classes, in some classes, rarely, never.

Allen, N., Morgan, M., Moore, T., & Snow, C. (1987). What experienced collaborators say about collaborative writing. Journal of Business and Technical Communications, 1,70–90. Applebaum, E., & Blatt, R. (1994). The new

American workplace. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Uni-versity Press.

Ashraf, M. (2004). A critical look at the use of group projects as a pedagogical tool. Journal of Education for Business, 79,213–216. Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of

Business (2005). Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accredita-tion. Tampa, FL: Author

Bacon, D. R., Stewart, K. A., & Silver, W. S. (1999). Lessons from the best and worst student team experiences: How a teacher can make a difference. Journal of Management Education, 23,467–488.

Bamber, E. M., Watson, R. T., & Hill, M. C. (1996). The effects of group decision support systems technology on audit group decision making. Auditing: A Journal of Theory & Prac-tice, 15,122–134.

Barker, R. T., & Franzak, F. J. (1997). Team build-ing in the classroom: Preparbuild-ing students for their organizational future. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 27,303–315. Batra, M. M., Walvoord, B. E., & Krishman, K. S.

(1997). Effective pedagogy for student-team projects. Journal of Marketing Education, 19(2), 26–42.

Bolton, M. K. (1999). The role of coaching in stu-dent teams: A ‘Just-in-Time’ approach to learn-ing. Journal of Management Education, 23, 233–250.

Boyer, E. G., Weiner, J. L., & Diamond, M. P. (1985). Why groups? The Organizational Behavior Teaching Review, 9(4), 3–7. Brooks, C. M., & Ammons, J. L. (2003). Free

rid-ing in group projects and the effects of timrid-ing, frequency, and specificity of criteria in peer assessments. Journal of Education for Busi-ness, 78,268–272.

Chen, G., Donahue, L. M., & Klimoski, R. J. (2004). Teaching undergraduates to work in organizational teams. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3,27–40.

Chen, Z., Lawson, R. B., & Gordon, L. R. (1996). Groupthink: Deciding with the leader and the devil. The Psychological Record, 46, 581–590.

Clinebell, S., & Stecher, M. (2003). Teaching teams to be teams: An exercise using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and the Five-Fac-tor Personality Traits. Journal of Management Education, 27,362–383.

Cohen, S. G., & Bailey, D. E. (1997). What makes teams work: Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. Journal of Management, 23,239–290.

Connerley, M. L., & Mael, F. A. (2001). The importance of invasiveness of student team selection criteria. Journal of Management Edu-cation, 25,471–494.

Cox, P. L., & Bobrowski, P. E. (2000). The team chapter assignment: Improving the effective-ness of classroom teams. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 1,92–103. Decker, R. L. (1995). Management team

forma-tion for large scale simulaforma-tions. In J. D. Overby & A. L. Patz (Eds.),Developments in Business Simulation & Experimental Exercises (pp. 128–129). Statesboro, GA: Association for Business Simulation and Experiential Learning. Deeter-Schmelz, D. R., Kennedy, K. R., & Ram-sey, R. P. (2002). Enriching our understanding

of student team effectiveness. Journal of Mar-keting Education, 24,114–124.

Deeter-Schmelz, D. R., & Ramsey, R. (1998). Stu-dent team performance: A method for class-room assessment. Journal of Marketing Educa-tion, 20,85–93.

Denton, H. G. (1994). Simulating design in the world of industry and commerce: Observations from a series of case studies in the United King-dom. Journal of Technology Education, 6, 1045–1064.

Dommeyer, C. J. (1986). A comparison of the individual proposal and the team project in the marketing research course. Journal of Market-ing Education, 8(1), 30–38.

Duemer, L. S., Christopher, M., Hardin, F., Olibas, L., Rodgers, T., & Spiller, K. (2004). Case study of the characteristics of effective leadership in graduate student collaborative work. Education, 124,721–727.

Erez, A., Lepine J. A., & Elms, H. (2002). Effects of rotated leadership and peer evaluation on the functioning and effectiveness of self-managed teams: A quasi-experiment. Personnel Psychol-ogy, 55,929–948.

Ettington, D. R., & Camp, R. R. (2002). Facilitat-ing transfer of skills between group projects and work teams. Journal of Management Edu-cation, 26,356–379.

Feichtner, S. B., & Davis, E. A. (1984). Why some groups fail: A survey of students’ experiences with learning groups. Organizational Behavior Teaching Review, 9,75–88.

Feichtner, S. B., & Davis, E. A. (1992). Collabo-rative learning: A sourcebook for higher edu-cation. University Park, PA: National Center of Postsecondary Teaching, Learning, and Assess-ment.

Forman, J., & Katsky, P. (1986). The group report: A problem in small group or writing processes? Journal of Business Communication, 23,23–35. Freeman, K. A. (1996). Attitudes toward work in project groups as predictors of academic perfor-mance. Small Group Research, 27(2), 265–282. Goretsky, M. E. (1984). Class projects as a form of instruction. Journal of Marketing Education, 6(3), 33–37.

Gregorich, S. E., Helmreich, R. L., & Wilhelm, J. A. (1990). The structure of cockpit manage-ment attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75,682–690.

Hackman, J. R. (Ed.) (1990). Groups that work (and those that don’t).San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Henke, J. W., Jr. (1985). Bring reality to the intro-ductory marketing student. Journal of Market-ing Education, 7(3), 59–71.

Hernandez, S. (2002). Team learning in a market-ing principles course: Cooperative structures that facilitate active learning and higher level thinking. Journal of Marketing Education, 24, 73–85.

Huff, L. C., Cooper, J., & Jones, W. (2002). The development and consequences of trust in stu-dent project groups. Journal of Marketing Edu-cation, 24,24–35.

Johnson, C., & Smith, F. (1997). Assessment of complex peer evaluation instrument for team learning and group processes. Accounting Edu-cation: A Journal of Theory, Practice, and Research, 2,21–40.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1975). Learn-ing together and alone: Cooperation, competi-tion and individualizacompeti-tion. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1984–85). Structuring groups for cooperative learning.

The Organizational Behavior Teaching Review, 9,8–17.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1990). Cooper-ative learning and achievement. In S. Sharan (Ed.), Cooperative learning: Theory and research(pp. 23–37). New York: Praeger Press. Johnson D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1998). Cooperative learning returns to college: What evidence is there that it works? Change, 30, 27–35.

Joyce, W. B. (1999). On the free-rider problem in cooperative learning. Journal of Education for Business, 74,271–274.

Koppenhaver, G. D., & Shrader, C. B. (2003). Structuring the classroom for performance: Cooperative learning with instructor-assigned teams. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 1,1–21.

Kunkel, J. G., & Shafer, M. L. (1997). Effects of student team learning in undergraduate auditing courses. Journal of Education for Business, 72, 197–200.

Latane, B. K., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 822–832.

Latting, J. K., & Raffoul, P. R. (1991). Designing student work groups for increased learning: An empirical investigation. Journal of Social Work, 27,48–59.

Levine, J. M., & Moreland, R. L. (1990). Progress in small group research. Annual Review of Psy-chology, 41,585–634.

McCain, B. (1996). Multicultural team learning: An approach towards communication compe-tency. Management Decision, 34,65–73. McCorkle, D. E., Reardon, J., Alexander, J. F.,

Kling, N. D., Harris, R. C., & Iyer, R. V. (1999). Undergraduate marketing students, group pro-jects, and teamwork: The good, the bad, and the ugly? Journal of Marketing Education, 21, 106–117.

McKendall, M. (2000). Teaching groups to become teams. Journal of Education for Busi-ness, 75,277–282.

McKinney, K., & Graham-Buxton, M. (1993). The use of collaborative learning groups in the large class: Is it possible? Teaching Sociology, 21,403–408.

Mello, J. A. (1993). Improving individual member accountability in small work group settings. Journal of Management Education, 17,253–259. Meyer, J. (1994, November). Teaching teams

through teams in communication courses: Let-ting structuration happen. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Speech Communica-tion AssociaCommunica-tion, New Orleans, LA.

Muller, T. E. (1989). Assigning students to groups for class projects: An exploratory test of two methods. Decision Sciences, 20,623–634. Newstrom, J., & Scannell, E. (1998). The big book

of team building games: Trust-building activi-ties, team spirit exercises, and other fun things to do. New York: McGraw–Hill.

Nichols, J. D., & Hall, J. (1995). The effects of cooperative learning on student achievement and motivation in a high school geometry class. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Francisco, CA.

Page, D., & Donelan, J. P. (2003). Team-building tools for students. Journal of Education for Business, 78,125–128.

Paswan, A. K., & Gollakota, K. (2004). Dimen-sions of peer evaluation, overall satisfaction, and overall evaluation: An investigation in a

group task environment. Journal of Education for Business, 79,225–231.

Pfaff, E., & Huddleston, P. (2003). Does it matter if I hate teamwork? What impacts student atti-tudes toward teamwork. Journal of Marketing Education, 25,37–45.

Quintessential Careers. (2004). Real world advice: Teamwork skills are in demand. DeLand, FL:Author. Rau, W., & Heyl, B. S. (1990). Humanizing the

college classroom: Collaborative learning and social organization among students. Teaching Sociology, 18,141–155.

Robbins, T. (1994). Meaningfulness and commu-nity in the classroom: The role of teamwork in business education. Journal of Education for Business, 69,312–316.

Rotfeld, H. (1998). Hello, bird, I’m learning ornithology. Marketing Educator, 17,4–6. Sheppard, J. A. (1995). Remedying motivation and

productivity loss in collective settings. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4,131–134. Siciliano, J. (1999). A template for managing teamwork in courses across the curriculum. Journal of Education for Business, 74,261–264. Slavin, R. E. (1990). Research in cooperative

learning: Consensus and controversy. Educa-tional Leadership, 47,52–55.

Stout, R. J., Salas, E., & Fowlkes, J. E. (1997). Enhancing teamwork in complex environments through team training. Group Dynamics, 1, 169–182.

Strong, J. T., & Anderson, R. E. (1990). Free-rid-ing in group projects: Control mechanisms and preliminary data. Journal of Marketing Educa-tion, 12,61–67.

Sundstrom, E. (1999). The challenges of support-ing work team effectiveness. In E. Sundstrom & Associates (Eds.),Supporting work team effec-tiveness: Best management practices for foster-ing high performance(pp. 3–23). San Francis-co: Jossey-Bass.

Sutton, J. C. (1995). The team approach in the quality classroom. Business Communications Quarterly, 58,48–51.

Taninecz, G. (1997). Best practices and perfor-mances. Industry Week, 246,28–43.

Tarricone, P., & Luca, J. (2002). Employees, teamwork, and social independence—a formu-la for successful business? Team Performance Management, 8,54–59.

Thacker, R. A., & Yost, C. A. (2002). Training students to become effective workplace team leaders. Team Performance Management, 8, 89–95.

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Development sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384–399.

Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. (1977). Stages of small group development. Group and Organi-zational Studies, 2,419–427.

Verderber, K. S., & Serey, T. T. (1996). Manag-ing in-class projects: SettManag-ing them up to suc-ceed. Journal of Management Education, 20, 23–38.

Williams, D. L., Beard, J. D., & Rymer, J. (1991). Team projects: Achieving their full potential. Journal of Marketing Education, 13, 45–53. Yamane, D. (1996). Collaboration and its

discon-tents: Steps toward overcoming barriers to suc-cessful group projects. Teaching Sociology, 24, 178–181.

Yeatts, D. E., & Hyten, C. (1998). High-perform-ing, self-managed work teams: A comparison of theory to practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

APPENDIX A

Recent Graduates Comments About Teamwork

Recent college graduates were asked about their college experiences and how they related to their current work experience, specifically related to teamwork. Here are their responses:

• “College was the ultimate test of teamwork, and nine out of 10 jobs require you to work with other people. If you aren’t willing to compromise how you work to fit the needs of others, you’re probably not going to make it very far.”

• “Teamwork skills are expected and demanded in my job. Being in sales requires me to communicate/work with pretty much every department in my company.” • “Teamwork is very important in the workplace, especially with regard to how you

communicate with the people you work with. My college education was okay for preparing me to participate in a team; however, I would have liked to have more group projects with an emphasis on presentations.”

• “People that can’t work in teams don’t last long in my line of work.”

• “Definitely my job wouldn’t happen without teamwork. College was more individ-ual for my studies, and it took some adjusting for me to learn how to adjust well in a team environment, because I have a very dominant, individual personality.” • “A lot of work is project-based, where you have anywhere from four to ten different

people staffed on a project. It is critical that you can handle your amount of work as well as be able to interact with all members of your team, including your boss.” • “Teamwork is definitely required, and although my education partially prepared me

for it, previous jobs and work-related experiences had more of an impact.” • “Teamwork skills are a must at my job. The many group projects really gave me a

taste for how to deal with group dynamics.”

• “There are few positions that don’t require teamwork on some level. I work with developers, producers, client operations, sales, and executive leadership. Teamwork is expected. If you can’t work well with others you’re never going to make it very far.”

• “Teamwork is essential for my job. You work with so many different organizations and personalities that teamwork is the only way to get things done the right way.” • “Teamwork skills are definitely important in the workforce and were NOT taught at

college [for me].”

• “All of my previous positions required teamwork. It is as crucial as your professional skills.”

Note.From Realworld Advice: Teamwork Skills Are In demand, by Quintessential Careers, 2004. Copyright 2004 by Quintessential Careers.

APPENDIX B

Benefits and Problems Associated With Group Projects

Benefits

Collaborative Learning

(Boyer, Weiner, & Diamond, 1985; Hernandez, 2002; Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991)

Experience With Complex Work

(Goretsky, 1984; Henke, 1985)

Realism or Emulating Work Environment

(Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991)

Improved Communication Skills

(Meyer, 1994; Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991)

Improved Interpersonal or Social or Team Skills

(Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 1998; Joyce, 1999; Kunz, 1994;

McCorkle et al, 1999; Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991)

Active or Advanced Learning

(Freeman, 1996; Johnson & John-son, 1984–85; Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991)

Persistence When Facing Adversity

(Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 1998)

Increased Knowledge Base or Deep Thinking

(Boyer, Weiner, & Diamond, 1985; Nichols & Hall, 1995)

Higher Student Motivation

(Denton, 1994; Dommeyer, 1986; Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 1998)

Positive Interdependence

(Joyce, 1999)

Greater Achievement

(Freeman, 1996; Johnson & John-son, 1984–85; JohnJohn-son, JohnJohn-son, & Smith, 1998)

Sense of Meaningfulness

(Robbins, 1994)

Improved Multicultural Relations

(McCain, 1996; Slavin, 1990)

Problems

Free-Riding or Social Loafing

(Ashraf, 2004; Joyce, 1999; Latane, Williams, & Harkins, 1979; McCorkle et al., 1999; Mello, 1993; Strong & Anderson, 1990; Williams, Beard, & Rymer, 1991)

Inadequate Rewards or Poor Grading Schemes

(Sheppard, 1995)

Behavioral or Attitude Problems

(Pfaff & Huddleston, 2003; Sutton, 1995)

Inferior Skills

(Sutton, 1995)

Lack of Leadership

(Forman & Katsky, 1981)

Specialization of Skills

(Batra, Walvoord, & Krishman, 1997)

Transaction Cost Issues

(Yamane, 1996)

Stifling of Individual Innovation or Creativity

(Batra, Walvoord, & Krishman, 1997)

APPENDIX C

Elements of the Most Satisfying Group Experience

Cooperation

• All group members worked hard and together • Group members were cooperative

• Group members worked well together • Team really came together

• Everyone worked hard to complete the project • Everyone worked well together

• Everyone worked productively and motivated each other • All group members contributed and were enthusiastic

Leadership

• Strong team leader or someone leading at all times • Organized leader

• Team leader was very organized

Relevancy

• Working with real businesses makes it more worthwhile • Relates to the real business world

Clear Goals

• Having a well-defined problem and examples of how it had been solved before • Having a clear-cut goal

• Clear goals

• Clearly defined goals

Specific Team Roles

• All members knew what was expected of them • Had clearly defined roles

• All members had their role and did their jobs

Interim Reports or Checkpoints

• Had deadlines and midpoint checks • Project guidelines and specific milestones • Checkpoints for progress

• Set due dates throughout semester