Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Administrative Tasks and Skills Needed for Today's

Office: The Employees' Perspective

Diane B. Hartman , Jan Bentley , Kathleen Richards & Cynthia Krebs

To cite this article: Diane B. Hartman , Jan Bentley , Kathleen Richards & Cynthia Krebs (2005) Administrative Tasks and Skills Needed for Today's Office: The Employees' Perspective, Journal of Education for Business, 80:6, 347-357, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.6.347-357

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.6.347-357

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 38

View related articles

oday’s office environment seems to require a different set of skills than in the past. The job market has shifted dramatically over the last sever-al years. Job titles and descriptions have been modified to accommodate those shifts. Employers increasingly empha-size the importance of skills crucial to employees’ abilities to work effectively. These skills include (a) knowing how to learn, think, and solve problems; (b) applying basic computing skills to workplace tasks; and (c) working in teams or groups. Other skills include being able to adapt, be flexible, and use personal management skills (Alpern, 1997; Clagett, 1997).

The changing nature of work is demanding more from employees than have historical arrangements, or work-place arrangements in the past (Capelli et al., 1997), especially in computer exper-tise. In 1999, the U.S. Census reported that 57% of employees over the age of 18 in the United States used a computer at work (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1999). Later Census reports (2000 and 2001) addressed computer usage at home but did not provide statistics on work-place computer usage. Developments in office technology will continue, and these developments will bring about fur-ther changes in the workplace.

Research before 2000 focused on the entry-level work skills that employers

wanted. Since then, two very important factors have changed the profile of the new entry-level worker: the rapidly changing technology and a major shift in the economy after Septem-ber 11, 2001. These factors justify the need for more studies on what skills and tasks employees actually perform.

Current research (e.g., U.S. Depart-ment of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2003) suggests the economy’s accelerated need for more highly educated workers is not being met. If educators are going to provide students with the office skills they need to be competitive in the work-force, they need to be aware of what skills and tasks employers expect of their employees. Then they need to know if the skills and tasks they teach actually match

those that are required in the workplace. A mismatch of skills and tasks could intensify the shortage of prepared work-ers. After there is a match between skills and tasks, the educators can update the curriculum.

The lack of literature on skills that are performed in the workplace raises sev-eral questions:

1. What are the most important skills and tasks for entry-level employees?

2. How do these tasks and skills differ from experienced employees?

3. Do experienced employees have more computer-related work tasks than do entry-level employees?

4. How dependent are both employee groups on emerging technology?

Answers to these questions may help educators design and update the curricu-lum in programs in which office skills and tasks are taught. Employers can also benefit from the answers to these questions by having access to skilled workers who are trained to handle posi-tions within their companies.

The purpose of this study was to con-tribute to the current literature by pro-viding updated information about what skills and tasks administrative employ-ees are actually performing. Findings support conclusions, teaching implica-tions, and topics suggested for further research.

Administrative Tasks and Skills

Needed for Today’s Office:

The Employees’ Perspective

DIANE B. HARTMAN JAN BENTLEY KATHLEEN RICHARDS

CYNTHIA KREBS

Utah Valley State College, Orem, Utah

T

ABSTRACT. Educators need to know which skills and tasks administrative employers are using. The results of this study revealed that higher-level skills are used more by experienced than by entry-level employees. Experienced employees performed more computer tasks and embraced technology more readily. Neither group was required to have certificates or certifications in the positions they held. All employees in the study had experienced increased workplace security, job restructure, and increased responsibilities. On the basis of these findings, the authors discuss the conclusions and teaching implica-tions and suggest topics for further research.

Literature Review

The Changing Workforce

“Change is the only true constant” (Capelli et al., 1997, p. 2) is a fitting prin-ciple to apply to the workplace. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, pressures from inside and outside the cor-porate structure have molded and shaped the workplace as we know it today.

In a study entitled Workforce 2000

(Wilhelm, 1999), the U. S. Department of Labor documented the expected shortage of skilled American workers in the rapidly changing global economy. The predictions were based on five demographic facts: (a) the population and the workforce will grow more slow-ly than at any time since the 1930s; (b) the average age of the population and the workforce will rise, and the pool of young workers entering the labor mar-ket will shrink; (c) more women will enter the workforce; (d) minorities will comprise a larger share of new entrants into the labor force; and (e) immigrants will represent the largest share of the increases in the population and the workforce since World War I.

The forecasted shortage of young people to fill positions in the new ser-vice economy is compounded by per-ceived inadequacy of their knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Reisch, 1997). A primary responsibility of educators is to help fill positions in this new economy with skilled workers.

Traditional skills and tasks that have proven to be valuable over time include answering telephones, operating the pho-tocopier, sorting and distributing mail, and maintaining records. Other advanced responsibilities have included composing and editing correspondence, recom-mending or making purchasing deci-sions, and handling traveling arrange-ments (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2003). The results of recent studies sug-gest that the role of an administrative assistant is expanding to include tasks such as meeting planning, software train-ing, and Web site maintenance (Interna-tional Association of Administrative Pro-fessionals, 2003). OfficeTeam suggests that Microsoft Office Specialist (MOS) Certification is important for today’s office employee (Robert Half Interna-tional, 2004). Because skill requirements

are constantly changing and expanding, it is difficult to find a survey that is com-pletely up to date. If such an up-to-date survey were available, it would be easy to update it as changes occur over time.

A Changing Skill Set

A body of literature (e.g., Gomes, 1998; Grevelle, 1999) suggests the skills required for successful job performance do not match the demographic make-up of the workforce. The skills gap is sim-ply the difference between the quantity and quality of a worker’s skills and the demands of a particular job. There are two schools of thought concerning this skills gap. First, the pool of workers is less qualified than were those in previ-ous times. Second, the job requirements increase over time and with innovation; but the worker’s abilities do not increase with them. Both are likely to be true (Wilhelm, 1999). The problem of a skills gap continues to persist and companies spend billions of dollars annually trying to boost productivity, yet they are failing because of “a very old-fashioned labor shortage” of skilled workers (Wilhelm, 1999, p. 108).

Efforts from both educators and employers to remedy the skills gap vary depending on point of view. Those who adhere to the “jobs are changing faster” theory address training in the workplace, and those who espouse the “poor gradu-ate skills” theory address education in the schools (Wilhelm, 1999, p. 108).

A major project was undertaken by the Secretary of Labor’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills (SCANS; 1991). This commission— composed of representatives from busi-ness, industry, labor, education, and government—spent 12 months talking to business owners, public employers, managers, union officials, and on-the-line workers in stores, offices, factories, and government offices in the United States. The findings of the commission were published in a series of publica-tions that began with a report entitled,

What Work Requires of Schools: A SCANS Report for America 2000

(SCANS, 1991). The findings published in the SCANS report have been widely accepted by business and industry (Har-ris, 1996; Sanchez, 1996; Wilhelm,

1999). The report, which detailed 36 skills and competencies described as workplace know-how, focused on (a) 20 competencies listed under 5 categories: resource management, interpersonal abilities, information management, sys-tems understanding, and technological abilities; and (b) 17 foundation skills listed under 3 categories: basic reading, writing, computation, and communica-tion skills; thinking skills; and personal qualities (SCANS, 1991).

A more recent study was conducted by the U.S. Department of Labor Statis-tics (2003). According to the Occupa-tional Outlook Handbook, 2002–03 Edi-tion (U.S. Department of Labor Statistics), employers are looking for strong communication skills and honesty or integrity when they evaluate college graduates as potential new hires. Every year from 1998 to 2003, employers have placed communication skills at the top of their wish lists for employees. They also prize job candidates who show experi-ence in teamwork, interpersonal skills, motivation, and initiative. They want to hire graduates who have a strong work ethic. Employers assert that new gradu-ates are lacking in many of these skills. They also say that recent graduates are not adept at speaking or writing. Many lack maturity; some are ignorant of busi-ness etiquette. Many new graduates have unrealistic expectations of the profes-sional world.

The overall concept of identifying specific skills and standards for jobs is not new to the field of education. How-ever, two notations are important with regard to the necessary skill require-ments in today’s flexible workplace: (a) market standard changes are not within control of a single organization but, rather, within a global society enveloped by fierce international competition; and (b) uncertainty dominates how skill changes are affected. The effects of change on skill requirements depends on the skill needed for specific jobs, occu-pations, industries, or firms (Sanchez, 1996).

METHOD

We selected a population (N = 26,703) consisting of members and affiliates of the International

tion of Administrative Professionals (IAAP) in our efforts to determine what workplace skills and tasks were required for entry-level and experienced administrative employees. The member-ship of the IAAP included over 40,000 entry-level and experienced office workers worldwide, and was an ideal group to give realistic insights into today’s administrative office skills and task requirements.

The sample population of 26,703 IAAP members consisted of members with electronic mail (e-mail) addresses, approximately 71.15% of membership (better than the 60% reported by more than 1,000 associations cited by Hart-man & HartHart-man, 2004). A stratified sample with proportional allocation, totaling 3,500 members in the United States and Canada, was selected for the study. Other international members, stu-dents, and retired members were excluded. A smaller sample of approxi-mately 100 members was selected from the Idaho-Oregon-Utah Division for a second study to cross-tabulate online results with print data.

Low mailing costs and timely data were the main reasons we chose an online survey for the first study. IAAP leadership supported this study by pro-viding names for a pilot test and for the online survey by sending a prenotice e-mail, an e-mail invitation with Web sur-vey link, and a follow-up reminder. In return, we shared decision making about the study timetable and the survey content and design. We also agreed to publish an article of research findings in IAAP’s OfficePROmagazine.

We followed college, state, and federal guidelines to protect privacy rights in both studies. We developed the online survey and ran a pilot test of the survey with 20 IAAP members. Twelve (60%) gave feedback to improve survey naviga-tion, instructions, question wording, and survey design. The final survey consisted of questions about workplace tasks and skills, use of technology, and required certifications (see Appendix for survey content). Questions ranged from yes/no answers, to multiple choice, to open-ended formats. We used a 4-point Likert-type scale to rate each office skill on a scale from 1 (very important), to 4 (not important), and a 6-point Likert-type

planning and coordinating meetings. We excluded the following work skills: honesty/integrity, teamwork, interper-sonal, motivation/initiative, strong work ethic, and flexibility.

In the first study, the administration options included (a) a unique Internet link that discouraged uninvited access and repeat survey submissions, (b) an immediate view of updated survey results, and (c) graphics in the header. A hardcopy version of the online survey from Study 1 was prepared for Study 2. The survey for Study 1 was released in mid-November 2002 and remained active for 3 weeks. Respondents could view the results for 33 days after Study 1 was released. We sent out a follow-up e-mail 2 weeks after the initial invitation. At the same time, we prepared and mailed research packets to the presidents of the chapters that were participating in Study 2. The surveys for Study 2 were completed in January, 2003. We ana-lyzed the basic statistics (arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and frequency counts) for both studies. We used chi-square statistics and Cramer’s coeffi-cients to evaluate existing relationships within populations. In addition, we used data gathered from open-ended com-ments to supplement quantitative data.

vey. Viewing, but not completing, the survey is referred to in current literature as the click-through rate,and is defined by Porter and Whitcomb (2003, p. 580) as “the percentage of respondents view-ing the first page of the survey but not submitting any results (as determined by the log files from the server).” The click-through rate may also be termed the nonresponse rate. The confidence interval for the sample population was 95%, with the margin of error ranging between 2.5% and 4.3%.

Of the 535 who responded to the first item, 425 (79.44%) indicated they were qualified to answer questions about an entry-level administrative position. These respondents were then branched (directed) to questions about entry-level employees, then to questions about their current positions. The 110 (20.56%) who responded that they were not qual-ified to answer questions about an entry-level administrative position were branched to questions about their cur-rent positions only.

An average of 341 (80.24% of the 425 qualified respondents) completed questions 2 through 8 about entry-level employees. We believe that 81 respon-dents terminated the survey after the first question possibly because the scale of frequency of tasks performed

was rated 1 (daily), 2 (weekly), 3 ( month-ly), 4 (quarterly), 5 (yearly), or 6 (never). Respondents did not respond by number, but clicked on the appropriate box under the selected word choice.

Work tasks in the survey focused on traditional office tasks and those related to emerging technology. Work skills focused mainly on making decisions, using critical thinking, planning and coordinating projects, communicating, training and supervising employees, and

RESULTS

About 10% of e-mail invitations in Study 1 were returned for faulty addresses, and we received only 2 e-mail messages from respondents asking questions or making requests. Of the approximately 3,150 electronic invita-tions that may have successfully reached respondents, 648 chose to view the survey (20.57% of 3,150 sample) and 113 (17.44% of 648 views) chose not to participate after viewing the

sur-Of the 535 who responded to the first item, 425

(79.44%) indicated they were qualified to answer

questions about an entry-level administrative

position.

instructions explaining the branching feature based on first-question respons-es was inadequate or because the respondent failed to click the submit button to trigger the branching feature. For remaining survey Questions 9 through 22 about experienced employ-ees, an average of 440 responded (82.24% of 535 completes). Approxi-mately 95 respondents who answered Question 1 did not complete the ques-tions about their current posiques-tions.

One can determine the response rate by using one of two approaches. First is the traditional approach: dividing the number of respondents completing the survey by the total sample population (minus returned messages). In this case, the response rate for this study was 16.98%. Second is an approach that con-siders the unique online environment. The number of respondents completing the survey is divided by the number viewing the survey (view rate). In this case, the response rate would be 82.56% for this study (see Table 1). Possible problems with using the view rate would include not knowing the following: (a) whether intended respondents actually saw that they had an electronic survey invitation, (b) whether respondents are from the sample population, (c) whether respondents are representative of the population, or (d) whether more than the intended respondents use the same elec-tronic address. As Leora Lawton, a member of the AAPORNET list serve suggested, “What’s the disposition for ‘there was so much spam in my inbox that I accidentally deleted the invite?’” (Lawton, 2004). As new as this alterna-tive calculation is in the literature, more research will be needed to verify its value or acceptance among researchers.

Of the surveys completed in the first study, 43.93% were submitted within 24 hr. Two weeks later, a reminder electron-ic message was sent, and an additional 26.36% of surveys were completed and

submitted within 48 hr. The remaining 31% of surveys came in during the 2-week period before the reminder was sent out.

Paper surveys in Study 2 were returned in February 2003, and we tab-ulated and compared the paper data with online data. We performed two chi-square analyzes: the first analyzed online responses with paper responses, and the second analyzed responses of entry-level employees with experienced employees. We also used Cramer’s coefficient because it is not affected by sample size and therefore is useful in situations in which a statistically signif-icant chi-square is suspected to be the result of a large sample size instead of any substantive relationship between the variables. Cramer’s coefficient is interpreted as a measure of the relative strength of an association between two variables (Friedman, 2001).

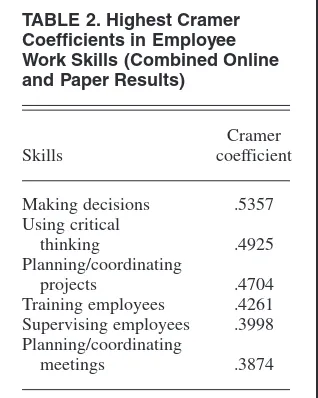

Coefficients comparing online and paper responses ranged from .1168 to .2273. Coefficients comparing entry-level and experienced employees ranged from .1168 to .5357. Cramer’s coeffi-cient must be between 0 and 1; and the higher the coefficient, the greater the difference in the distributions of the two samples. The largest coefficient differ-ences were between entry-level and experienced employees, especially in the work skills area (see Table 2).

Some tasks reflected a commonality between employee groups. These tasks were rated as the top daily tasks, and few differences existed between entry-level and experienced employees (see Table 3). Nevertheless, differences exist; respondents indicated that higher-level skills are used by people with more experience. Although responses reflected that computer tasks are used by both employee groups, in some areas, experienced employees seemed to have more computer tasks than did entry-level employees (see Table 4).

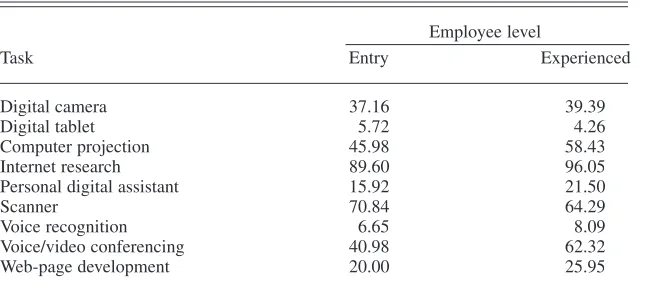

How closely associated are the two employee groups in using emerging tech-nology? (Emerging technology would include the personal digital assistant (PDA), digital tablet, voice-recognition software, Web-page development, voice/ video conferencing, computer projection system, scanner, digital camera, and Internet research. We found that both groups used the technology, but at differ-ent levels (see Table 5). Knowledge over experience was reflected in the use of the digital tablet and scanner between the two groups. The least-used technology was voice recognition, although experienced workers seemed to be ahead of new-entry employees in embracing the technology.

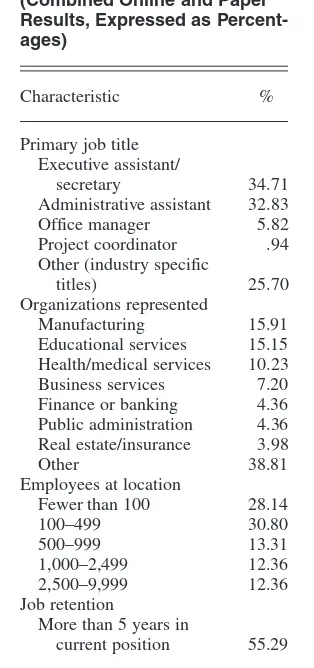

One notable feature of respondent demographics was that 72.17% of expe-rienced employees were not required to have certificates or certifications in their current positions. An even higher num-ber, 90.52%, of entry-level employees were not required to have certificates or certifications for their positions. Only .8 of 1% of respondents from both groups were required to have a Microsoft Office Specialist (MOS) certificate. The most frequently required certificates were the Certified Professional Secre-tary (CPS) and Certified Administrative Professional (CAP).

Since September 11, 2001, both employee groups have experienced increased workplace security (60.50% of respondents) and computer security (53.86%). Workplace and computer

TABLE 1. Comparison of Response Calculations (Online Survey)

Survey sample source No. Completions Response rate (%)

Electronic invitations mailed 3,150 535 16.98 Survey views 648 535 82.56

TABLE 2. Highest Cramer Coefficients in Employee Work Skills (Combined Online and Paper Results)

Cramer Skills coefficient

Making decisions .5357 Using critical

thinking .4925 Planning/coordinating

projects .4704 Training employees .4261 Supervising employees .3998 Planning/coordinating

meetings .3874

Note. Respondents answered as very im-portant.

security relates to workplace practices to discourage workplace violence, ter-rorist acts, and computer identity theft. Workplace and computer security also promotes responsible information-handling practices among employees. Thirty percent of respondents reported job restructuring with more responsi-bilities because of downsizing. Only 20.47% experienced no change in their jobs as a result of September 11, 2001. For other demographic features about survey respondents, see Table 6.

CONCLUSION

Emerging new technology has changed the nature of work and placed increased demands on employees. The changing workplace has had an impact on everything from job titles and descriptions to the technology used to accomplish business tasks. In the pre-sent study, we found that 79.53% of entry-level and experienced employees indicated that their responsibilities had changed for various reasons since

Sep-tember 11, 2001. As a result, employees at either level will face constant changes in their careers and will need to upgrade their skills. Employees with excellent skills are needed to work effectively in a fast-paced work environment.

This study sought to determine the most important skills and tasks that entry-level employees use and perform in today’s office and to find out if these skills differ from those of experienced employees. The results showed that some common skills are used frequently by both groups, for example, using the tele-phone, photocopying, processing mail, and maintaining records. Experienced employees performed some skills at a much higher rate than did entry-level employees. Those skills included making decisions, using critical thinking, plan-ning and coordinating projects, traiplan-ning employees, supervising employees, using accounting procedures, and planning and coordinating meetings.

The study also looked at how computer-related tasks varied between the two groups and how dependent employees are on emerging technology. A high per-centage of each group used electronic mail and word processing. However, experienced employees used other com-puter tasks such as spreadsheets, data-base, electronic presentations, Internet research, and software integration at a higher rate than entry-level employees. Emerging technology is used by both groups at varying levels, but knowledge of how to use the technology seemed to be more important than years of work experience.

Employees have indicated that the higher-level skills are used by people who have more experience. Work experience over newly acquired knowledge in school seems to be more important in today’s workplace. Educators need to require stu-dents to complete an internship or coop-erative work experience in an office as part of their administrative assistant degree program, Employers attending a March 2004 business advisory committee meeting reinforced that an internship or cooperative work experience while in school is one of the most important fac-tors that they consider when hiring new graduates (BCIS Advisory Board, 2004). Experienced employees indicated that potential hires need to have sound

TABLE 3. Most Frequent Employee Daily Tasks (Combined Online and Paper Results, Expressed as Percentages)

Employee level

Task Entry Experienced

Telephone 99.76 99.25 Photocopying 98.57 96.03

Mail 95.99 88.72

Electronic mail 95.73 98.30 Word processing 92.24 92.15 Filing/records management 73.82 71.80

TABLE 4. Differences in Frequent Employee Daily to Monthly Tasks (Combined Online and Paper Results, Expressed as Percentages)

Employee level

Task Entry Experienced

Accounting 55.11 75.56

Database 66.19 74.10

Electronic presentations 44.53 57.62 Internet research 77.54 89.47 Spreadsheets 85.85 90.21 Software integration 61.15 75.28

TABLE 5. Daily to Yearly Use of Emerging Technology (Combined Online and Paper Results, Expressed as Percentages)

Employee level

Task Entry Experienced

Digital camera 37.16 39.39 Digital tablet 5.72 4.26 Computer projection 45.98 58.43 Internet research 89.60 96.05 Personal digital assistant 15.92 21.50

Scanner 70.84 64.29

Voice recognition 6.65 8.09 Voice/video conferencing 40.98 62.32 Web-page development 20.00 25.95

technology skills. Educators need to teach emerging technologies such as voice recognition, tablet PCs, digital tablets, PDAs, and Web development in their programs.

Seminars and conferences offered by colleges and universities provide busi-ness employees with training for new skills and technologies. Colleges and universities, in return, gain from the

knowledge of current business require-ments. Educators must incorporate the new technologies in the curriculum as it becomes available to ensure that new graduates are prepared to move into the workforce. Educators must learn new technologies themselves; one of the best ways to do that is to attend their profes-sional association conferences where many of the emerging technology skills are taught.

Further research needs to be conducted on what skills and tasks employees are actually using in the modern office so that educators can maintain currency in their programs and send highly prepared employees into the workplace.

REFERENCES

Alpern, M. (1997). Critical workplace competen-cies: Essential? Generic? Core? Employability? Non-technical? What’s in a name? Canadian Vocation Journal,32(4), 6–16.

Barton, P. E. (1997). Toward inequality: Disturb-ing trends in higher education. Princeton, NJ: Policy Information Center, Educational Testing Service.

Business Computer Information Systems Advisory Board. (2004, March). Minutes of meeting at Utah Valley State College, Orem.

Cappelli, P., Bassi, L., Katz, H., Knoke, D., Oster-man, P., & Useem, M. (1997). Change at work. New York: Oxford University Press.

Clagett, C. (1997). Workforce skills needed by today’s employers (Market Analysis MA98–5). Largo, MD: Prince George’s Community Col-lege, Office of Institution Research and Analysis. Friedman. H. H. (2001, February). Sample crosstabulation problems. Retrieved October 28, 2003, from http://academic.brooklyn.cuny. edu/economic/friedman/crosstabulation.htm Gomes, J. (1998). High and dry: Shortage of

high-tech workers is hurting business productivity. The Wall Street Journal Classroom Edition, 6(7), 1–5.

Grevelle, J. (1999). The next generation of tech prep. High School Magazine, 6(6), 32–33.

Harris, G. (1996). Identification of the workplace basic skills necessary for effective job perfor-mance by entry-level workers in small busi-nesses in Oklahoma. Unpublished doctoral dis-sertation, Oklahoma State University. (Digital Dissertations, 2589464)

Hartman, L. D., & Hartman, D. (2004) Online sur-veys: The hidden challenges to successfully using them. Manuscript submitted for publica-tion.

International Association of Administrative Pro-fessionals. (2003). Document new skills devel-oped on (and off) the job. Retrieved October 13, 2003, from http://iaap-hq.org/ResearchTrends/ document_ new_skills.htm

Lawton, L. (2004, February 22). View rates to cal-culate response rates. Message posted to AAPORNET mailing list, archived at http://lists.asu.edu/archives/aapornet.html Occupational Outlook Handbook. (n.d.) Retrieved

June 30, 2003, from http://www.bls.gov/oco/ ocos127.htm

Porter, S. R., & Whitcomb, M. E. (2003). The impact of contact type on web survey response rates. Public Opinion Quarterly,6,579–587. Reisch, M. (1997). U.S. manufacturers say

work-ers lack basic skills. Chemical and Engineering News,75, 11–12.

Robert Half International, Inc. (2004). Skills in demand. In Officeteam salary guide(pp.4–5). Menlo Park, CA: Author.

Sanchez, D. (1996). Understanding the skills gap: A descriptive approach for capturing the inte-gration of firm, industry, and job-level varia-tions in skills requirements. Unpublished doc-toral dissertation, University of Wisconsin– Madison. (Digital Dissertations, 2589475) Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary

Skills (SCANS). (1991). What work requires of schools: A SCANS report for America 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. United States Department of Commerce. (1999).

United States Census Bureau. Total using com-puter at work. Washington, DC: Author. U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor

Statis-tics. (2003). Occupational outlook handbook, 2002–03 edition. Job outlook 2003. Retrieved January 2003 from http://www.jobweb.com/ joboutlook/default.cfm

Wilhem, W. J. (1999). A Delphi study of entry-level workplace skills, competencies, and proof-of-achievements products. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal,41, 105–22.

TABLE 6. Respondent Profile (Combined Online and Paper Results, Expressed as Percent-ages)

Characteristic %

Primary job title Executive assistant/

secretary 34.71 Administrative assistant 32.83 Office manager 5.82 Project coordinator .94 Other (industry specific

titles) 25.70 Organizations represented

Manufacturing 15.91 Educational services 15.15 Health/medical services 10.23 Business services 7.20 Finance or banking 4.36 Public administration 4.36 Real estate/insurance 3.98 Other 38.81 Employees at location

Fewer than 100 28.14 100–499 30.80 500–999 13.31 1,000–2,499 12.36 2,500–9,999 12.36 Job retention

More than 5 years in

current position 55.29

APPENDIX Office Skills Survey

1. Questions 2-7 relate to a person in an entry-level administrative positionin your organization.

Do you feel qualified to answer questions about an entry-level administrative position?

Yes No

2. Please specify how often in your organization a person in an entry-level administrative position would perform the following:

Daily Weekly Monthly Quarterly Yearly

Word Processing (create/edit/maintain) Spreadsheet (create/manipulate/maintain) Database (create/manipulate/maintain) Electronic presentations (create/edit) Software integration (use two or more software packages in a document/project) Internet research

Web page (design/develop/maintain) Electronic messages (send/receive/schedule) Telephone calls (make/receive/screen) Mail functions

Accounting/bookkeeping Filing/records management

3. What other tasks not mentioned in Question 2 would an entry-level administrative per-son perform in your organization?

4. Please indicate how frequently in your organization a person in an entry-level admin-istrative position would use the following technology:

Daily Weekly Monthly Quarterly Yearly

Photocopier Fax (standalone) Fax (computer)

Personal digital assistant (PDA) Digital tablet

Voice-recognition software Voice/video conference Computer projection system Scanner

Digital camera

5. What other technology not listed in Question 4 would an entry-level administrative person use in your organization?

(appendix continues)

6. Please rate the following categories of work skills. Do not rate them against each other, but consider each skill individually as to its importance in an entry-level administrative position in your organization.

Very Somewhat Not Important Important Important Important

Use critical thinking Make decisions

Use written interpersonal communication Use verbal interpersonal communication Greet or meet public/customers Work with vendors

Make travel arrangements

Use records/information management Deliver presentations

Plan/coordinate meetings Plan/coordinate projects

Troubleshoot software/equipment Initiate or deal with workplace security Supervise employees

Hire employees Train employees

7. Which of the following certificates/certifications does your organization require of entry-level administrative employees when hired?

CPS CAP CMP MOUS None

Other (please specify)

8. Questions 9-15 relate skills and tasks for your current positionin the organization.

9. Please specify how often you perform the following tasks:

Daily Weekly Monthly Quarterly Yearly

Word Processing (create/edit/maintain) Spreadsheet (create/manipulate/maintain) Database (create/manipulate/maintain) Electronic presentations (create/edit) Software integration (use two or more software packages in a document/project) Internet research

Web page (design/develop/maintain) Electronic messages (send/receive/schedule) Telephone calls (make/receive/screen) Mail functions

Accounting/bookkeeping Filing/records management

(appendix continues)

10. What other tasks not mentioned in Question 9 do you perform?

11. Please indicate how often you use the following technology:

Daily Weekly Monthly Quarterly Yearly

Photocopier Fax (standalone) Fax (computer)

Personal digital assistant (PDA) Digital tablet

Voice-recognition software Voice/video conference Computer projection system Scanner

Digital camera

12. What other technology not listed in Question 11 do you use?

13. Please rate the following categories of work skills. Do not rate them against each other, but consider each skill individually as to its importance in your current job.

Very Somewhat Not Important Important Important Important

Use critical thinking Make decisions

Use written interpersonal communication Use verbal interpersonal communication Greet or meet public/customers Work with vendors

Make travel arrangements

Use records/information management Deliver presentations

Plan/coordinate meetings Plan/coordinate projects

Troubleshoot software/equipment Initiate or deal with workplace security Supervise employees

Hire employees Train employees

14. Which of the following certificates/certifications are required for your current position?

CPS CAP CMP MOUS None

Other (please specify)

(appendix continues)

15. In what areas has your job changed since September 11, 2001? (Choose all that apply.)

Workplace security Increased computer security Recruiting/hiring procedures Training/retraining

Job restructure—less responsibilities due to upsizing Job restructure—more responsibilities due to downsizing Increased telecommuting

No change

Other (please explain)

16. Questions 17-22 help us better understand your current job position and your member-ship in IAAP.

17. What is your primary job title? (Please select one from the following list.)

Executive Assistant Administrative Assistant Office Manager

Data Entry and Information Processing Worker Receptionist/Front Desk Worker

Office Clerk, General

Customer Service Representative Information and Records Clerk Desktop Publisher

Project Coordinator

Web Design/Internet Specialist Other (please specify)

18. How long have you worked in your current position?

Less than 1 year 1 to 2 years 3 to 5 years 6 to 10 years 11 to 15 years 16 to 20 years Over 20 years

19. Which of the following types best describes your organization?

Business services Communications

Educational services/academic institution Finance/banking

Health/medical services Hospitality

Manufacturing Public administration Real estate/insurance Retail

Transportation Wholesale/distribution

Home-based business (self-employed) Other (please explain)

(appendix continued)

20. Approximately how many people are employed at your location?

Fewer than 100 100-499 500-999 1,000-2,499 2,500-9,999 10,000 or more

21. Of which IAAP districts are you a member?

Great Lakes Northeast Northwest Southeast Southwest Canada

22. Are you currently or have you been an IAAP officer at the chapter, division, or district level?

Yes No

Please contact hartmadi@uvsc.edu if you have any questions regarding this survey.