Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:05

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Evaluating a Short-Term, First-Year Study

Abroad Program for Business and Engineering

Undergraduates: Understanding the Student

Learning Experience

Josephine E. Olson & Kristine Lalley

To cite this article: Josephine E. Olson & Kristine Lalley (2012) Evaluating a Short-Term, First-Year Study Abroad Program for Business and Engineering Undergraduates: Understanding the Student Learning Experience, Journal of Education for Business, 87:6, 325-332, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.627889

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.627889

Published online: 30 Aug 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 267

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.627889

Evaluating a Short-Term, First-Year Study Abroad

Program for Business and Engineering

Undergraduates: Understanding the Student Learning

Experience

Josephine E. Olson and Kristine Lalley

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USAThe authors describe a short-term study abroad program for business and engineering students at the end of their freshman year, and then present the results of a later survey of the participants as upperclassmen that was conducted to determine whether the program met its objectives. The primary objectives of this first-year program were to influence participants to pursue additional study abroad opportunities later in their college career, inspire them to further study foreign language and culture, and encourage them to become involved in additional international activities. Improvement in teamwork and cross-cultural skills were also goals.

Keywords: assessment of learning outcomes, freshmen programs, international business edu-cation, joint business and engineering programs, study abroad

Incorporating an international experience into business and engineering undergraduate education is becoming an in-creasingly common practice. In the 10 years between 1998 and 2008 the number of U.S. business and manage-ment students studying abroad increased 31% from about 23,000 to 53,000. The number of U.S. engineering stu-dents studying abroad increased 23% from about 3,600 to 8,100 (Bhandari & Chow, 2009). Short-term programs (2–8 weeks) have also grown in importance, with 56% of all U.S. students going abroad participating in this type of program in 2008 (Institute of International Education, 2009; McMurtrie, 2009). Although the number of engineer-ing students who study abroad is much smaller than the num-ber of business students who study abroad, both disciplines recognize the benefits of having students include an interna-tional experience as part of their education. We describe a short-term study abroad program developed for University of Pittsburgh business and engineering students at the end of their first year of study, and then discuss the results of an evaluation survey of the participants two to three years later.

Correspondence should be addressed to Josephine E. Olson, University of Pittsburgh, Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

BACKGROUND

Study abroad programs for first-year undergraduate students in professional schools are fairly rare, as are joint study abroad programs for business and engineering students. Our program, nicknamed the Plus3 program because students earn an additional three credits, was designed by business and engineering faculty in cooperation with the Study Abroad Office. The idea of a program for first-year students was to give them a short, structured, faculty-led international pro-gram early in their college career that would help students overcome any initial anxiety about foreign travel and whet their appetite for more international activities, foreign lan-guage study, and more focused study abroad programs or international internships later in their college career. Anxiety about foreign travel was found to be the second most impor-tant issue after expenses for why students were relucimpor-tant to study abroad in a survey of Oregon State University students (King & Young, 1994). Other goals were to increase their cross-cultural sensitivity and ability to work in diverse teams. The rationale for bringing engineering and business students together was that these students would inevitably work to-gether in their careers, often in an international context, and thus should learn how to interact on business and engineer-ing teams at an early stage of their academic development.

326 J. E. OLSON AND K. LALLEY

Combining freshmen from the two schools also allowed us to offer more country destinations.

Study abroad programs for first-year students present challenges. Because these students typically have not yet developed content-specific knowledge in a particular field of study, programs must take into account that participants know little about U.S. business and engineering practices, let alone about business and engineering practices in other countries. In addition, many of the students have not traveled abroad before and, as freshmen, are still adjusting to living on their own for the first time and being independent from their parents. The program was developed with these con-straints in mind; details of the program are described in the next section.

Although short-term study abroad programs have become a more dominant model of study abroad in higher educa-tion in recent years and several studies have demonstrated the benefits of the short-term program model (Anderson, Lawton, Rexeisen, & Hubbard, 2006; Chieffo & Griffiths, 2004), there are few studies that report on learning outcomes several years after students have participated in such pro-grams (Martin, Bradford, & Rohrlich, 1995). This study as-sesses the perceptions and activities of students from the Plus3 program two to three years after they participated in the program, in terms of how they report what they learned and the subsequent activities and choices the students made to enhance their international awareness.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PLUS3 PROGRAM

As noted previously, the Plus3 short-term study abroad pro-gram is offered to business and engineering freshmen en-rolled at the University of Pittsburgh. The Plus3 program includes predeparture class meetings, a two-week interna-tional trip to a country immediately after spring classes end, and a team-based research paper presented the following September. There are no language requirements for the pro-gram. To participate, students complete an application and are accepted into the program based on the following criteria. Students must have completed two semesters at the Univer-sity of Pittsburgh with a 2.75 grade point average (GPA) for business students and a 2.50 GPA for engineering students. Students under university disciplinary sanctions are not ad-mitted. In their application students can order their choices for country destination, but there is no guarantee that they will all get their first choice. Finally, they are interviewed by the faculty leader and the study abroad assistant to deter-mine whether the student has the appropriate motivation and maturity for the program.

The Plus3 program began in 2002 with two destinations: Germany and the Czech Republic. For this study we surveyed participants from the 2005 and 2006 programs. In 2005, there were five destinations: Santos, Brazil; Valpara´ıso, Chile; Beijing, China; Rouen, France; and Augsburg, Germany.

In 2006, there were only four destinations, as France was dropped. In each of these two years, the tuition and fees for all destinations were the same, but students paid their own airfare, which varied by destination. The program typically has about 100 students participating (20–30 from business and 70–80 from engineering).

The program has three components, as recommended for short-term study abroad field trips (McLaughlin & Johnson, 2006). The pretrip classes totaling 12 hr are used to prepare students for their international experience. They learn a little about the country they will visit and its cultural aspects, par-ticularly business and engineering practices. Because com-pany visits are a major part of the trip, students are assigned to company teams and begin researching their companies; they make a presentation on their company before the trip. These pretrip classes are also used to convey expectations about proper behavior on the trip and particularly on com-pany visits. Students are presented with a code of conduct, which they must sign to indicate their agreement. They gen-erally have a survival language class; however, for several of the destinations, particularly Chile, some students already have adequate or even advanced foreign language skills.

During the two-week trip to their country, the participants stay at one location in either an inexpensive hotel or student dormitories and make day trips. Staying in one location re-duces the cost and the stress of frequent moves. There are four or five company visits. Company visits to manufacturing firms where students can see products being made work bet-ter for these younger students, even the business ones, than visits focused on strategy, marketing, finance, or research and development. In addition, there are lectures, sightseeing trips, and cultural activities. In most of the destination countries, the students also have the opportunity to interact with local students. Students must keep a professional journal and they are also graded for their participation in the trip activities.

Upon their return to the United States, the student teams write a research paper on their company and the global in-dustry in which it operates, and then make a PowerPoint presentation to faculty and students from the business and engineering schools at the beginning of the fall term of their sophomore year.

Survey of Learning Outcomes

All Plus3 participants have been required to fill out an eval-uation at the end of the international trip. However, the orga-nizers were interested in knowing whether the program was meeting the longer term objectives of the program. In the spring of 2008 one of the authors developed an online sur-vey to help determine how well the program was meeting its goals. As listed previously, the goals of the program are influ-encing participants to pursue additional study or internship abroad opportunities later in their college career, inspiring students to further study foreign languages, and encourag-ing students to become involved in additional international

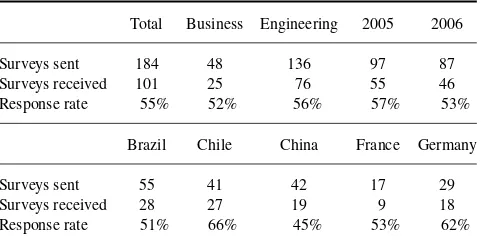

TABLE 1

Surveys Sent and Response Rates, by Category

Total Business Engineering 2005 2006

Surveys sent 184 48 136 97 87

Surveys received 101 25 76 55 46

Response rate 55% 52% 56% 57% 53%

Brazil Chile China France Germany

Surveys sent 55 41 42 17 29

Surveys received 28 27 19 9 18

Response rate 51% 66% 45% 53% 62%

activities, such as joining an international organization or at-tending internationally focused events. Additional goals are to increase the students’ ability to work in interdisciplinary teams and to develop greater cultural sensitivity.

The survey asked a number of questions related to these goals; it also asked for information on students’ international experience and language study before participating in the Plus3 program. The survey design included closed questions that would allow us to compare responses across our pop-ulation, as well as open-ended questions that would allow participants in the study to describe their experiences and perspectives in greater detail, and that would allow us to gain a more in-depth understanding of the perceptions of the par-ticipants about the program (Cresswell, 1998; Patton, 1990).

The Sample

Those surveyed were students who participated in the Plus3 program in 2005 and 2006. Surveys were sent out electron-ically to all those participants still at the university during the spring of 2008, and three follow-up emails were sent to those who had not responded. The survey had Institutional Research Board approval and all respondents were guaran-teed anonymity.

Table 1 lists the number of surveys sent and received and the response rates by categories. The overall response rate was 55%, and response rates by school and year varied from 52% to 57%; response rates by destination varied from 45% to 66%.

SURVEY RESULTS

The quantitative analysis of the data collected includes simple counts, chi-square tests, and analysis of variance using SPSS (ver. 15).

Table 2 indicates some pre-Plus3 program characteristics of the respondents. The table shows that three-fourths of the respondents were from the school of engineering. Prior to participating in the Plus3 program, only 36% of the respon-dents had traveled abroad; thus, the majority of sturespon-dents had

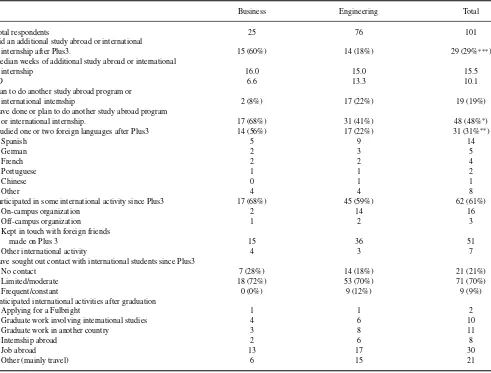

TABLE 2

Numbers and Characteristics of the Respondents

Business Engineering Total

Total respondents 25 76 101

International experience before Plus3 15 (60%) 21 (28%) 36 (36%∗∗) Foreign language studied before

Plus3

One foreign language 15 (60%) 61 (80%) 76 (75%) Two foreign languages 5 (20%) 7 (9%) 12 (12%) Languages studied before Plus3

no international experience. The business students had sig-nificantly more international experience than the engineering students,χ2(1,N=101)=8.59,p<.003, with 60% of the

25 business students having been abroad for at least two weeks and only 28% of the 76 engineering students having been abroad for at least two weeks.

Table 2 also indicates that 87% of the students had studied one or two foreign languages before participating in the Plus3 program, with the most common language being Spanish; there were no statistically significant differences between the schools. We expected those who participated in 2005 to be seniors and we asked how many were graduating in April 2008 and thus completing their degree in four years. Of the students, 58% expected to graduate in April 2008, 100% of the business students and 43% of the engineering students.

Before examining the learning outcomes, we comment on some of the information in Table 2 and in the text. The fact that there were more than twice as many engineering students as business students was partly a function of dif-ferences in the sizes of the freshman classes. In 2005 and 2006 the College of Business Administration (CBA) had a first-year class size of about 310 students, while the Swan-son School of Engineering (SSOE) had a first-year class size of about 450 students. Even so, the percentage of freshman participants from engineering was also greater (about 22%) than the percentage from business (15%). Other possible ex-planations for the difference in numbers include the fact that engineering students had required classes in the fall of the freshmen year where the program could be promoted whereas the business students only had a one-credit workshop taught by nonfaculty advisors. Although the Plus3 program was designed as a teaser for subsequent deeper study abroad programs, the rigidity of the engineering curriculum of-ten makes it more difficult for engineering students to do a semester or summer-length study abroad program (Fis-cher, 2010; King & Young, 1994). Our conversations with

328 J. E. OLSON AND K. LALLEY

engineering students suggest that some of the engineer-ing students chose the Plus3 program as their only inter-national experience because they were afraid they would be too busy with such obligations as cooperative educa-tion (in which the student works in industry for alternat-ing semesters throughout his or her college career) and other engineering activities later on in their studies. In con-trast, the authors talked to a number of business students who said they knew they wanted to do a longer study abroad program and therefore did not enroll in the Plus3 program.

It is not clear why more business students had traveled abroad than engineering students; explaining the difference would require more information on the socio-economic char-acteristics of the two student bodies and of the participants (Salisbury, Umbach, Paulsen, & Pascarella, 2009). The fact that all the 2005 business participants in the survey expected to graduate in the spring of 2008 but less than half the 2005 engineering participants were graduating then may reflect that many engineering students participate in cooperative education that delays their graduation. Next we examine questions with respect to desired outcomes of the Plus3 program.

Additional Study Abroad or Foreign Internships

One goal of the Plus3 program is to encourage students to participate in another, longer study abroad program or an international internship during their college studies. The re-sults shown in Table 3 indicate that 29% of the respondents did at least one more study abroad program and/or internship after Plus3, and 19% planned to do another program; thus, 48% either had done or expected to do another study abroad program. However, there were significant differences in the responses by school. On the one hand, business students were significantly more likely to have studied again or worked abroad than engineering students (60% [15] of business stu-dents versus 18% [14] of the engineering stustu-dents), χ2(1, N =101)=15.89,p<.001. On the other hand, 22% (17)

engineering students still planned to do another study abroad or international internship before graduation versus only 8% (2) of the business students (some cells were too small for a chi-square test). Combining these two responses, 68% (17) of business students who participated in Plus3 either studied abroad again or planned to go abroad a second time versus 41% (31) of the engineering students. The difference between the percentage of business students and the percentage of en-gineering students who had done or planned to do a study abroad program or an international internship is also statis-tically significant, χ2(1,N =101)=5.59,p <.018. This

finding supports the earlier suggestion that, for many of the engineering participants, the Plus3 program was the primary international experience for them. For those who did another study abroad or internship program the second experience

was a median of 15–16 weeks (roughly a semester) for both schools.

Additional Language Study

Another goal of the Plus3 program is to encourage students to continue to study foreign language(s) after completing the Plus3 program. The results indicated that 31% of the respon-dents continued to study one or two foreign languages after participating in the Plus3 program, with Spanish once more being the most common language studied. There were signif-icant differences between the schools, with 56% of business students continuing language study versus 22% of the engi-neering students,χ2(1,N=101)=10.00,p<.002.

Participation in International Activities and International Contacts

Still another goal of the Plus3 program is to get students interested in participating in international activities both dur-ing college and after graduation. As shown in Table 3, 61% of the respondents (68% of the business students and 59% of the engineering students) became involved with one or more international activities upon returning to the university after participating in the program. The differences between the two schools are not statistically significant. Table 3 also lists the type of activities by school. Participants were also asked: “To what degree have you sought out contact with international students?” Seventy percent of the respondents had limited or moderate contact and 9% had frequent or constant contact. The business students were somewhat less likely to have any contact. Many of the students also planned international activities after graduation, with 30% (23) of the engineers and 60% (15) of the business students planning to do an internship or pursue a full-time position abroad after graduation.

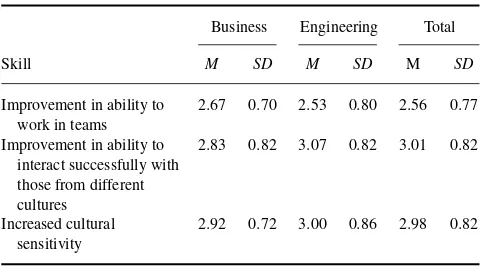

Teamwork and Cultural Sensitivity

It was hoped that the Plus3 experience would improve the ability of students to work in teams, be culturally sensi-tive, and interact effectively with those from outside of the United States. Respondents were asked, “To what extent has the Plus3 experience affected your ability to work well in teams?” and had to respond on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (none) to 4 (significant). The results are shown in Table 4. The mean of 2.56 fell between limited and mod-erate; differences between the schools were not statistically significant. Twelve percent of the respondents did not think Plus3 had an impact on their teamwork skills. Using the same 4-point scale, respondents were asked, “To what extent has the Plus3 experience improved your ability to interact successfully with those from different cultures?” The mean response was 3.01, the moderate score; differences between the schools were not statistically significant. Only 4% said it had no effect. Again using the same 4-point scale, the students

TABLE 3

Outcomes From Participation in Plus3

Business Engineering Total

Total respondents 25 76 101

Did an additional study abroad or international

internship after Plus3. 15 (60%) 14 (18%) 29 (29%∗∗∗)

Median weeks of additional study abroad or international

internship 16.0 15.0 15.5

SD 6.6 13.3 10.1

Plan to do another study abroad program or

international internship 2 (8%) 17 (22%) 19 (19%)

Have done or plan to do another study abroad program

or international internship. 17 (68%) 31 (41%) 48 (48%∗)

Studied one or two foreign languages after Plus3 14 (56%) 17 (22%) 31 (31%∗∗)

Spanish 5 9 14

German 2 3 5

French 2 2 4

Portuguese 1 1 2

Chinese 0 1 1

Other 4 4 8

Participated in some international activity since Plus3 17 (68%) 45 (59%) 62 (61%)

On-campus organization 2 14 16

Off-campus organization 1 2 3

Kept in touch with foreign friends

made on Plus 3 15 36 51

Other international activity 4 3 7

Have sought out contact with international students since Plus3

No contact 7 (28%) 14 (18%) 21 (21%)

Limited/moderate 18 (72%) 53 (70%) 71 (70%)

Frequent/constant 0 (0%) 9 (12%) 9 (9%)

Anticipated international activities after graduation

Applying for a Fulbright 1 1 2

Graduate work involving international studies 4 6 10

Graduate work in another country 3 8 11

Internship abroad 2 6 8

Job abroad 13 17 30

Other (mainly travel) 6 15 21

∗p=.05.∗∗p=.01.∗∗∗p=.001.

were asked, “To what extent has the Plus3 program increased your cultural sensitivity?” The mean overall response was 2.98, or approximately the moderate score; differences be-tween the schools were not significantly different. Seven per-cent said it had no effect.

After each of these three closed questions, students were given a chance to write open-ended comments. Themes from these responses are addressed in the next section. The themes were identified using thematic analysis, which is a process for encoding qualitative information (Boyatzis, 1998). A theme is a pattern found in the information that describes and orga-nizes possible observations (Boyatzis). Using this approach, we analyzed the open-ended comments to come up with the themes outlined subsequently.

Comments on teamwork. For the 12 students who did not believe the Plus3 program had helped their team skills, the explanations were generally that they had learned teamwork elsewhere, there was not much teamwork, or their Plus3 team

did not function well. Themes that emerged from the other 82 participants’ comments, who thought it had improved their teamwork skills and wrote comments, included the impor-tance of group dynamics and relying on others when in an overseas environment. The German Plus3 program had Uni-versity of Pittsburgh students work on company projects with students from the University of Augsburg and some of these Pitt students included comments on learning how to work with students from different cultures. Some of the students who thought they learned teamwork skills also commented about having lots of teamwork in other situations or not need-ing much teamwork for the project, but many commented on the value of teamwork in Plus3.

For example, a business student who went to Germany wrote, “Plus3 group work gave great experience on how to interact with students from different countries.” An engi-neering student who went to China said, “We had to work in teams on our projects, and while we were in China, we relied a lot on the other students because we were out of place.”

330 J. E. OLSON AND K. LALLEY

TABLE 4

Mean Extent of Improvement in Skills

Business Engineering Total

Skill M SD M SD M SD

Improvement in ability to work in teams

2.67 0.70 2.53 0.80 2.56 0.77

Improvement in ability to interact successfully with those from different cultures

2.83 0.82 3.07 0.82 3.01 0.82

Increased cultural sensitivity

2.92 0.72 3.00 0.86 2.98 0.82

Note.Improvement was rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (none) to 4 (significant).

Another engineering student on the China trip commented, “Teamwork and growing close to people in groups was es-sential on our trip to China, and it taught me to recognize my own shortfalls and strengths and to know when to count on others.” Although not directly commenting on teamwork, an engineer who went to France wrote, “I feel like Plus3 is an excellent introduction to new cultures and new environ-ments. . . It certainly lays the foundation for cross-cultural teamwork.” An engineering student who went to Brazil said, “Being put into groups with students I’m not familiar with has allowed me to practice basic skills in communication and getting along, even if it’s not project-oriented.” Some also commented that working virtually over the summer was a new challenge and others that they had learned how to handle difficult people and to work with people in different disciplines.

Comments on interacting with those from other cultures. For the 24 students who said Plus3 had no or limited effect on their ability to interact with people from other cultures, the most common explanations given were that they had already known how to interact or that there was little interaction with foreigners on the trip. From the 74 participants who said Plus3 had moderate or significant effect, the comments indicated that participants gained an awareness of how to effectively interact with people from other cultures. Participants also gained a better perspective of what it means to be a U.S. citizen and how that factor impacts the types of interactions the students have with those from other countries. Experiencing what it means to be a U.S. citizen in a foreign country led many of the participants to develop more awareness of how they come across to those from another culture and how they communicate to those who may not speak English as their first language. Some examples of their comments follow.

An engineering student who went to Chile wrote, “I would have had no idea how to act in a foreign environment, but now I have a good idea.” A business student who also went to

Chile said, “It helped me to understand that small differences in cultures can be very important.” An engineering student who went to France commented, “Basically I went from not knowing anything about the different culture, feeling awk-ward and unsure about interacting with foreign students, to a comfortable degree when I interact in an international en-vironment.” An engineering student who went to Germany observed, “Life outside of America! What a thought. Se-riously, though, I hadn’t really ever seen America from a different angle before so going abroad was worth it for that benefit alone.” Finally, an engineering student who went to Brazil wrote, “I understand that you must first observe how different cultures conduct business in order to be efficient and productive when working internationally.”

Comments on becoming more culturally sensitive.

The explanations given for answers to this question were quite similar to those to the previous question. The 19 who responded that Plus3 had limited or no effect on their cultural sensitivity generally argued that they already were sensitive to other cultures. Most of the other 77 participants who wrote comments thought that they had become more sensitive and some said that they were now more aware of their own U.S. culture. The following are a few of the comments.

An engineering student who went to Brazil observed: “I am aware that many Latin American countries are totally different and I think many Americans have a stereotype that everyone eats tacos and wear sombreros.” Another engineer who went to Brazil observed, “I learned a lot about the United States and my wastefulness by traveling abroad.” A business student who went to China said, “I am now more prepared when talking with or about other cultures to accept differ-ences in social norms and respond appropriately to ques-tions.” An engineering student who went to China wrote, “I’m much less na¨ıve now. I’m from a very small, very xeno-phobic town. . . Now I think I really empathize with all cultures and stick up for them when ignorant people from my hometown talk down on anyone for having a different culture.”

Additional Comments on the Plus3 Experience

Finally there was an open-ended question unrelated to a pre-vious closed question that allowed respondents to comment on what was the most significant effect of the Plus3 program on each of them. The question read, “What stands out to you as the most helpful or meaningful part(s) of the Plus3 experience that has or will impact you?” A total of 82 of the 101 participants chose to write comments. Fifty-two com-mented on the opportunity to make friends and interact in an-other culture, and 26 mentioned company visits and learning about business and engineering in another country. Seventeen respondents pointed out that they planned to pursue addi-tional internaaddi-tional experiences as a direct result of having participated in the Plus3 program. The following are some

examples of responses: A business student who went to Chile wrote, “[It made] me realize that I definitely wanted to study abroad in the future and possibly even work and live abroad one day.” Another business student who went to Chile said, “The trip has also inspired me to study abroad again and pursue an international business certificate.” An engineering student who went to China commented, “It broadens your view of the engineering industry beyond the United States. Seeing the profession in a different cultural setting gives a better appreciation for it.” An engineering student who vis-ited Brazil wrote, “I was convinced I wanted to obtain my engineering degree after spending time touring engineering facilities in my Plus3 country.” An engineering student who went to Germany observed,

It gave me the desire to go out and experience the world. . .to

not be such an isolationist. Since Plus3 I’ve been back to Germany twice already, once to visit and another time to do research for the University of Hamburg. It’s also inspired me to study abroad at Oxford University in the United Kingdom for a year, something I wouldn’t have dared to do without the confidence gained from this experience.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The results of this survey show that about half of the students who participated in this short-term study abroad program participated in or planned to participate in another study abroad program or an international internship, about a third continued with language study, and most participated in in-ternational activities and sought out inin-ternational students after the program. However, it should be noted that business students were much more likely than engineering students to achieve two of the major objectives of the Plus3 program—to do another international program and to continue language programs. If these two objectives are equally important for engineering students, then more research is needed to deter-mine how these can be better achieved within the constraints of the engineering curriculum.

Most of the respondents thought that their teamwork, cultural sensitivity, and ability to interact with others from another culture had improved as a result of the program. These results represent only the opinions of the respon-dents. More objective examinations of improvement in cul-tural sensitivity might be achieved by administering a stan-dard test of cultural sensitivity before and sometime after the program.

As the comments to the last open-ended question indicate, the Plus3 program apparently helped many of the student par-ticipants become more engaged with the world around them, and more aware of how they should interact with those who are from different cultures. Also, the comments suggest that the Plus3 program helped students become more focused and confident about themselves. These findings, in our opinion,

need more exploration. As a learning outcome, it is surpris-ing that students would report such transformative learnsurpris-ing as an outcome from participating in a short-term study abroad program, where the general view among practitioners is that short-term study abroad programs do not allow for sufficient time or opportunities to develop such important and lasting change in participants. However, at least two studies did not find any significant difference in global-mindedness of stu-dents in short- and long-term programs (Donnelley-Smith, 2009; Kehl & Morris, 2008).

Last, the results seem to indicate that many of the pro-gram objectives were met, particularly for business students. However, given the Plus3 program was voluntary and only a small number of students in both schools participated, it can-not be stated with certainty if the program primarily attracted already globally minded students or those who recently became proponents of globalism. Most had not traveled abroad before the program, but they might still have been internationally focused. We would like to conduct another study with a control group of students who did not engage in the Plus3 program to determine differences in those stu-dents’ attitudes and beliefs about international experience. We are also curious about those students who did not par-ticipate in the Plus3 program, but who did parpar-ticipate in an international education program later in their college career, to see if there are differences with that population in how they view their own awareness of international is-sues. A longer-term study of career outcomes is likewise desirable.

REFERENCES

Anderson, P. H., Lawton, L., Rexeisen, R., & Hubbard, A. (2006). Short-term study abroad and intercultural sensitivity: A pilot study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30, 457–469. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.1-.004

Bhandari, R., & Chow, P. (2009).Open doors 2009: Report on international education exchange. New York, NY: Institute of International Education. Boyatzis, R. (1998).Transforming qualitative information: Thematic

anal-ysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chieffo, L., & Griffiths, L. (2004). Large-scale assessment of student atti-tudes after a short-term study abroad program.Frontiers: The Interdisci-plinary Journal of Study Abroad,10, 165–177.

Creswell, J. W. (1998).Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Donnelley-Smith, L. (2009). Global learning through short-term study abroad.Peer Review,11(4), 12–15.

Fischer, K. (2010, April 2). U. of Minnesota integrates study abroad into the curriculum.The Chronicle of Higher Education,56(29), A26–A27. Institute of International Education. (2009). Briefing: Americans study

abroad in increasing numbers. Retrieved from http://www.iie.org/who- we-Are/News-and-Events/Press-Center/Press-Releases/2009/2009-11-16-Americans-Study-Abroad-Increasing

Kehl, K., & Morris, J. (2008). Differences in global-mindedness between short-term and semester long study abroad programs at selected private universities.Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad,

15, 67–80.

332 J. E. OLSON AND K. LALLEY

King, L. J., & Young, J. A. (1994). Education for the 21st century.Die Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German,27, 77–87.

Martin, J., Bradford, L., & Rohrlich, B. (1995). Comparing predeparture ex-pectations and post-sojourn reports: A longitudinal study of U.S. students abroad.International Journal of Intercultural Relations,19, 87–110. McLaughlin, J. S., & Johnson, D. K. (2006). Assessing the field course

experiential model; transforming collegiate short-term study abroad ex-perience in rich learning environments.Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad,12, 65–80.

McMurtrie, B. (2009, November 20). Study abroad programs diversify as their popularity grows.The Chronicle of Higher Education,56(23), A24. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/section/Home/5

Patton, M. (1990).Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Salisbury, M. H., Umbach, P. D., Paulsen, M. B., & Pascarella, E. T. (2009). Going global: Understanding the choice process of the in-tent to study abroad. Research in Higher Education, 50, 119–143. doi:10.1007/s11162–008–9111-x