Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Technology, Preprocessing, and Resistance—A

Comparative Case Study of Intensive Classroom

Teaching

Marco Adria & Teresa Rose

To cite this article: Marco Adria & Teresa Rose (2004) Technology, Preprocessing, and

Resistance—A Comparative Case Study of Intensive Classroom Teaching, Journal of Education for Business, 80:1, 53-60, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.1.53-60

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.1.53-60

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 29

View related articles

ntensive classroom delivery is the offering of a course within a real period of time that is significantly smaller than the conventional period of time. For example, an intensive class-room course may be offered over 5 or 6 full days of instruction instead of in the more conventional 3 hours of instruc-tion per week over 12 weeks. The num-ber of hours spent in instruction may be the same in the two delivery options, but the scheduling is different. The inten-sive classroom delivery of graduate-level university courses in business is a significant development because it is associated with the application of infor-mation and communications technolo-gies (ICTs). ICTs provide the organiza-tional capacities required to alter the conventional university schedule of studies. Intensive classroom delivery, therefore, leads to questions about how and why ICTs are used in higher educa-tion, along with the question of what role faculty members will have in plan-ning for and using these technologies.

In this article, we present two case studies of business-related courses that were taught by the authors in 2001 through intensive classroom delivery at two universities. Before the presenta-tion of the cases, we explore the context of institutional change in higher educa-tion, especially how that change is enabled and influenced by ICTs. This

context is characterized in part by the assumption that more intensive plan-ning—or, in the language of informa-tion systems, preprocessing—can be used to stimulate institutional innova-tion and change in higher educainnova-tion. ICT use in this sense is a consequence of political change. The institutional context is characterized also by the structuring influence of technology, through which technology is an antecedent, or even a cause, of change. The use of ICTs in this sense creates new opportunities in teaching and learning and leads to different ways of thinking about the instructor’s role.

We use the two cases as an heuristic to explore the meaning of alternative

course development and delivery in higher education. We report on the main characteristics of the respective courses that we taught and investigate how intensive classroom delivery both dif-fered from and resembled our previous teaching experiences. Our objective was to establish the basis for further inquiry into the significant question of how relationships among educational mar-kets, institutions of higher education, and professional autonomy are influ-enced mutually by the introduction of ICTs in the graduate-level university classroom. We also considered the potentials and pitfalls of intensive class-room delivery.

ICTs as Both Effect and Cause of Change in Higher Education

The use of ICTs to support teaching and learning in higher education has expanded in range and frequency over the past decade (Albert & Thomes, 2000; Annand, 1999; Jennings, 1995). ICTs are now commonly used in universities and colleges to support many activities asso-ciated with teaching and learning. These activities include planning and develop-ment of courses and curricula (Clouse & Nelson, 1999–2000), communication between instructors and administrators (Black, 2000), student-to-student and stu-dent-to-instructor interactions (Bullen,

Technology, Preprocessing,

and Resistance—

A Comparative Case Study of

Intensive Classroom Teaching

MARCO ADRIA TERESA ROSE

University of Alberta InnerWorks Consulting Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

I

ABSTRACT. In this article, the authors report on two international case studies that used comparable applica-tions of information and communica-tion technologies (ICTs) and were undertaken in comparable academic areas and levels of study. In the two cases, the authors explored faculty resistance to the use of ICTs for teach-ing and learnteach-ing in higher education. The two cases differed in institutional context and some student characteris-tics. The cases were significantly simi-lar in the codification of teaching and learning activities using ICTs. This codification is associated with an occa-sion for transforming the role of the instructor. The authors present poten-tials and pitfalls of this teaching mode.

VIEWPOINT

1998; Paj & Wallace, 2001), support ser-vices to students (Potter, 1997), and man-agement of the educational process (Adria & Woudstra, 2001; Ingram, 1999–2000). ICTs are of interest to uni-versities in part because of their ascribed capacity to stimulate sociotechnical change. We can consider the following ways in which ICTs function as a response to political change.

Information and communications technologies form part of a response by universities to political changes, but they are also a structuring influence on institutions of higher education. New network forms of organization emerge as outcomes of the use of ICTs. These new organizational forms, in turn, tend to accelerate the structuring influence of ICTs. Network organizations can be vir-tual extensions of the organization using technology to connect and work with external individuals and entities to per-form specific tasks. Examples of net-work organizations in higher education cited by Woudstra and Adria (2003) include consortia (Connecticut Distance Learning Consortium), arrangements between public universities and private companies (Global University Alliance), virtual networks (Universitas 21), and core-rings (Open University’s Profes-sional Development Europe).

Postgraduate programs of study have provided distinct examples of how teaching and learning systems in univer-sities may be redesigned comprehen-sively. In many cases, colleges and uni-versities are designing new programs for mature students who are already in the workplace and who are seeking a broader knowledge of their professional areas as well as updated management and communication skills. As Farring-ton (1999, p. 38) noted,

[s]ome of the most promising new appli-cations of information technology are in programs of postgraduate education designed to provide lifelong learning for mature students. Digital media have liber-ated traditional educational institutions from the constraints of their real estate.

The intensive classroom as a teaching and learning model for graduates in uni-versities combines the application of ICTs with a network form of organiza-tion. The intensive classroom is thus one of the outcomes of the expanding

introduction of ICTs into college and university classrooms.

Some observers have argued that there is a need for less emphasis on information transfer to passive students and more emphasis on teaching meth-ods that allow students to construct their own knowledge and skills. Mundell and Pennarola (1999), for example, urged the use of extensive group work that uses technology as a group facilitator for achieving higher-level learning. Lengwick-Hall and Sanders (1997) argued that the increasing diversity of students has been one of the major chal-lenges facing universities. They show that a wide range of individual learning styles, cultural orientations, experi-ences, and interests must be met with a similarly diverse range of learning options if a higher quality of learning and satisfaction is to be achieved. New technologies provide more opportuni-ties for matching diverse teaching meth-ods to diverse student needs.

Barriers to the Application of ICTs in Higher Education

Institutional Barriers

In spite of their increasing use, ICTs are not fully a part of university teaching and learning. Barriers to the application of ICTs in such models as the intensive classroom exist at the institutional and political levels and at the level of the individual faculty member. Institutions rely heavily on extrinsic rewards, which tend to be tied to research accomplish-ments (“Work of Faculty” 1994). Such an emphasis makes teaching activities, including those associated with alterna-tive delivery, somewhat less attracalterna-tive to faculty members. Research brings pres-tige, new students, and financial resources to the university. In her review of the literature on faculty participation in distance education in the United States, Wolcott (2003) cited the follow-ing “institutionally embedded disincen-tives” with regard to the use of ICTs in higher education: lack of rewards, lack of administrative or technical support, lack of training, lack of adequate com-pensation, and lack of clear commitment to or policy on distance education.

Piotrowski and Vodanovich (2000)

suggested that certain faculty members will have to lead in the use of technology. Because incentives are weak, in this view the decision to use Web-based teaching rests largely on the shoulders of individ-ual faculty members (Khan, 1997).

Faculty Barriers

Fearing agents of “soft control,” facul-ty members may resist the systematic and widespread use of ICTs. Because their professional identity is concerned in part with autonomy and the exercise of professional discretion, faculty members may see ICTs as a potential or actual threat. Wolcott (2003) discussed the fol-lowing faculty perceptions and attitudes that have contributed to resistance: fears associated with the use of technology, fear of being displaced, fear of losing autonomy or control over the teaching and learning process, and fears and uncertainty regarding the tenure and pro-motion process and job security.

Thomas (2000) suggested that although there are potentially signifi-cant benefits to using the Internet in teaching and learning, there are numer-ous obstacles to realizing those bene-fits. A further concern of faculty mem-bers is research that shows no significant differences between online and classroom courses in terms of stu-dent participation, stustu-dent interaction, and exam performance. For example, although interaction is easier in the classroom, there are advantages that support interaction through Internet courses, such as reflection time, reduced social presence, and idea refinement (Arbaugh, 2000). Arbaugh found a gender difference with regard to Internet participation: Women had a higher response rate in Internet courses. On the basis of this evidence, it is diffi-cult to argue that Internet courses are “worse” than traditional classrooms. On the other hand, some may question why they should give up the classroom when the online alternative seems to offer a marginal improvement, if any.

Faculty members will tend to scruti-nize innovation in the design and deliv-ery of their courses as long as the online mode is associated with issues that are a potential threat to the autonomy of the academic profession. New technologies

require faculty members to abandon many conventional practices and rela-tionships and perhaps find new ways to define themselves and what they do, and this is difficult. Of concern to faculty members is the fact that online courses raise the issue of who owns the intellec-tual property residing in course materi-als (Giroux, 2002; Oravec, 2003). Online courses are also commonly asso-ciated with temporary and part-time work (Noble, 2001).

The issue of faculty resistance is an important object of analysis in both the tool and proxy theories of educational technology. In the tool view, faculty resistance is a kind of unwelcome vari-able that potentially can be eliminated or mitigated by adjusting other vari-ables, such as training, technical sup-port, or instructional design learning (Kennepohl, 2001; Ng, 2000; Orlikows-ki & Iacono, 2001; Robson, 2000). Fur-thermore, the use of technology for teaching is, in this view, largely an enhancement. ICTs are a means, among others, of achieving the outcome of stu-dent and instructor satisfaction. As such, technology is not likely to contribute to substantive or enduring conflicts in val-ues. Faculty resistance is problematic from this perspective, but it is not con-sidered to be symptomatic of larger organizational or social conflicts. The proxy view, on the other hand, sees technology as part of a larger organiza-tional and social web of substantive conflicts (Boshier & Onn, 2000; Noble, 1995; Orlikowski & Iacono; Sumner, 2000). In this view, faculty resistance is not likely to subside quickly and is regarded as evidence of the essential threat that technology poses to the live world of human interaction and cooper-ation (Sumner).

Although the use of ICTs in teaching and learning is accepted widely within the limited environment of distance education and open learning, it is not as welcome in conventional university teaching. In spite of efforts to encourage integration of ICTs into the classroom, and as a means of leveraging efforts to initiate distance-education operations, ICTs continue to be seen by convention-al university faculty members as a kind of interloper, and no more than a possi-ble enhancement of the classroom.

The two cases in our study1provide a

means of examining the source and con-sequences of the institutional and faculty barriers to the effective use of intensive graduate classrooms. Each instructor (and author) reflected on the experience of teaching using the intensive classroom mode of delivery. The observations that were recorded were informed by aggre-gated data from evaluation question-naires completed by students after the completion of the course.

Case Study 1: “Human Communications,” Graduate Communications Program, Western Canadian University

Institutional and Political Context

This master’s program is offered through both the classroom and online modes of delivery. The program was developed to provide new opportunities for graduate-level study to more mature students, especially those who already are working full time in a professional area. The program was established as an innovation within the home university and in the regional political system. Government in the region supported both the curriculum and the alternative delivery methods. The curriculum of the program is communications and tech-nology, an interdisciplinary area that tends to attract the interest of working professionals such as public relations practitioners, information technology managers, and human-resource profes-sionals. Of the 10 courses in the pro-gram, four must be taken in the class-room through intensive delivery, three must be taken online, and three electives can be taken in a mode chosen by the student. Our first case involves a course providing an introductory survey of communications theory offered to 1st-year students. For this course, students were in class on 14 consecutive morn-ings or afternoons for 3 hours each day, for a total of 42 hours of instruction.

Use of ICTs

Each classroom course in the pro-gram includes a precourse activity along with readings made available online. Each course also allows for the

submis-sion of one of the major assignments 2 or 3 weeks after the conclusion of the classroom component. All the course syllabus information in the case was posted on the Web site in the relevant sections. Students were expected to familiarize themselves with the expecta-tions and rhythms of the course by read-ing the Web site thoroughly before they arrived so they would be able to partici-pate fully at the outset of classes. Stu-dents read as many of the assigned chap-ters in the text as possible beforehand.

After arriving for the intensive class-room sessions, students reported that they had read the material for Week 1, as directed. Also before arriving, they pre-pared their first assignment according to the directions provided on the Web site. This assignment was a 500-word narra-tive description of the communications theory for which they had the most affin-ity. Some students also began greeting one another before classes by posting messages on the Web-site conference area. This online dialogue was casual and unstructured, but it meant that most students had already made initial contact with one another by the time they arrived for their first class. During the 3 weeks of classes, a major theoretical approach was covered each day. A lec-ture was followed by a presentation on that day’s theory by a small group of stu-dents. Small-group and class discussion activities were also part of each day.

Student Characteristics

There were 22 students in the class. English was a first language, or a well-developed second language, for all stu-dents. A small number of students had distance-education experience, but most did not. None reported experience with intensive delivery. Most students (63%) were women. Most were 30 to 50 years old (72%), and only 9% were under 30 years of age. Most students had a degree in arts (34%), science (17%), or educa-tion (19%).

Observations

For the visiting professor from Cana-da to Australia (the second author), finalizing the objectives of the course for posting on the course Web site was a

major task and was comparable in time commitment and energy to teaching a conventional course. For example, reflecting on and revising the course objectives from a previous offering of the course to align it with intensive delivery led to changes in readings and other aspects of the course, all of which had to be completed before the first class. Although the classroom contact time of 42 hours was comparable to the 39-hour contact time provided in a con-ventional classroom at the university, the preparation required for the inten-sive classroom course was estimated to be about double that required for a con-ventional classroom.

With the extensive planning carried out, the reward for the instructor and the students was a organized and well-received course. All 20 students in the course completed an evaluation ques-tionnaire. Of the 20 respondents, 11 “strongly agreed” and 9 “agreed” that the “goals and objectives of the course were clear.” A total of 18 “strongly agreed,” and 2 “agreed” that they had increased their “knowledge of the sub-ject area.”

The classroom experience was dynamic and energetic. Students came prepared to discuss course-related issues and to present their ideas to their colleagues in discussion and through assignment presentations. For example, one pair of students made a presenta-tion on the second day of classes. The presentation required a significant amount of reading and discussion for preparation, but students were willing and able to present early on in the course because of the reading, study, and orientation activities that had taken place before the first day of classes.

For a graduate-level course, it was not enough to gain knowledge and receive information. A process of enhancing students’ critical and analyti-cal skills was expected. In spite of the fact that the course was taught over a relatively short period of time (3 weeks), 17 students “strongly agreed” and 3 “agreed” that the course had chal-lenged them “to think critically about the issues.”

Students got to know one another through the team-based presentations and during class time. They took the

opportunity of the relatively short period of time that they had together to make connections that would be extended to the online activities later in their pro-gram. The socializing aspect of the course—which was to set the stage for online activities in other courses in the coming months—was therefore integrat-ed into the classroom activities.

Case Study 2: “Globalization and Business Management,”

Graduate Business Program, Western Australian University

Institutional and Political Context

The visiting professor from Canada was in Australia for the purpose of teaching Globalization and Business Management as part of the International Master of Business Administration (MBA) program. The previous instructor for this course had resigned recently and suddenly from his position, and no one within the university was immediately available to assume the vacancy. At the same time, there were funds available within the university that could be applied for and, if granted, used for cre-ating innovative teaching models using ICTs. Through already evolving research relationships between profes-sors at both universities, discussions per-taining to a visiting position began, and the instructor made a 2-week visit to Australia beginning in the second week of the MBA students’ semester. Global-ization and Business Management was one of the core courses within the 2-year MBA program and was the only course offered in an intensive mode in which ICTs played a significant role.

The institutional demand for the pro-gram was based on the following strate-gies: (a) seeking market-driven degree programs to maintain and increase enrollment levels, (b) attempting to rationalize the financial resources devoted to teaching and research, and (c) seeking to demonstrate some level of innovation or exploration with regard to the institution’s core activities. The management faculty members were concerned particularly with pleasing students and meeting their demands. Perhaps as a consequence, prerequisites for the course were not established.

Well-established criteria for registering for the course were not followed. The department also encouraged instructors to allow students to register after the registration deadline and even after classes had begun.

Use of ICTs

The theoretical material was presented to students in 3- to 4-hour time frames every day for 2 consecutive weeks, resulting in just over 30 hours of inten-sive delivery of theoretical material. This was done primarily through lectures, fol-lowed by in-class, large- and small-group discussions. Before the beginning of the course, the instructor assigned the textbook supporting the lectures and posted more than 200 PowerPoint slides highlighting the key points of the lec-tures on the course Web site. The prepa-ration of slides for the entire course con-tent forced the instructor to keep a fast pace throughout the 2-week period, as subsequent material required the learn-ing of all previous slides. In other words, the instructor lost the usual ability to remove and add slides or to use her dis-cretion and move at a slower pace— options that are taken for granted in a tra-ditional course offering of 3 hours for 13 consecutive weeks. Furthermore, some students with greater technological capa-bility, a stronger foundation supporting the material, and with time and interest, had prepared the posted slides, making changes to the course content or compo-nents of it practically impossible.

After the intensive 2-week theoretical instruction, there was an extended intrasemester break (a result of the Syd-ney Olympics held that year), after which an instructor from the Australian University conducted several small-group tutorials twice a week, for 2 hours each time, for a period of 4 weeks. The tutorials consisted of student presenta-tions, discussions, and debates around cases that called for the application of the theoretical material learned in the first 2 weeks of classroom sessions. For tutorial preparation, a synchronous online chat system was established for each class. There were also asynchro-nous online discussions of the theoreti-cal and case materials that were moder-ated by both instructors.

Finally, the students and instructors met together via videoconference (between Canada and Australia) for a 2-hour session intended to allow for integration of the materials and a clo-sure to the course. This videoconfer-ence was led by the Canadian instructor and included a lecture followed by a question-and-answer session. Students were asked to submit questions before the videoconference, so the instructor could address these concerns in a time-ly manner within the teleconference presentation. There was a significant cost to the teleconference, so prepro-cessing of materials for the session was deemed necessary. Once again, the instructor had little discretion to take the real-time session in a number of learning directions. Instead, the well-devised plan was followed. The video-conference session was deemed a huge success by technicians, administrators, students, and instructors. The Aus-tralian University felt that it had con-nected to North America in a way that it had not before.

Student Characteristics

There were 68 students, and almost all were men. It was an ethnically diverse group, with a majority being from India (70%), many Asians (25%), and a few Europeans (3%). None were from North America or Australia. Most, but not all, of the students had under-graduate degrees in business. The focus of those business degrees, however, var-ied significantly. Although the course was recommended to students who were in their final year of the 2-year MBA, many were 1st-year students who were granted permission to enroll. Most of the students were young and had very little work experience, though the amount varied.

English was the second language for a majority of students, and there was great diversity among students in their spoken and written command of Eng-lish. This factor had implications for discussions in class, discussions in tutorials, and online communication. Students clearly clustered into cultural groupings when completing course work requiring interaction and collabo-ration. In summary, students’

prepara-Observations

For the Canadian instructor (the sec-ond author), the preparation time for this course exceeded preparation time for the same offering in the traditional delivery method. Although the actual in-class time (just over 30 hours) was less than the usual 39 hours of in-class time, the requirement of having the entire course content online before starting the course necessitated a higher level of organiza-tion and greater articulaorganiza-tion of the goals, objectives, content, and evaluative method than usual. Also, the fact that the course was offered in a different universi-ty setting required the instructor to understand and respond to the adminis-trative details of the institution and to become somewhat familiar with its tech-nology. Time also was required to meet and build a relationship and a plan for working with the Australian instructor who was teaching the tutorials. Addition-al time was required to learn the mechan-ics of videoconferencing successfully.

The preprocessing time and time put into the course paid off in what students generally described in evaluations as a well-organized and well-presented course. A Student Evaluation of Educa-tional Quality (SEEQ) was conducted

the students indicated that the pace of the course was too fast. There was con-siderable agreement among students that the course was more difficult and the workload heavier compared with their other subject areas. In qualitative responses provided by the SEEQ, most students emphatically stated that the pace of the course was too fast for the complexity of the topic. Many com-mented that the format did not allow the best integration of theory and practical application. However, 77% evaluated that they agreed or strongly agreed that the class was intellectually challenging and stimulating. Approximately 91% agreed that they had learned something that they considered valuable.

From an instructor perspective, the 2-week intensive classroom delivery followed by tutorials was a decision couched in administrative possibility rather than a decision that was learner focused. However, the alternative would have been to cancel the offering for a semester or more. Once the course became an administrative possibility, the university sought to have a large number attend. This created the situa-tion in which diverse professional and educational backgrounds of students came together with great variations in tion for the course differed from that

typically found in a North American MBA curriculum; their ways of partici-pating in class and their preferred ways of interacting with instructors differed from the North American model as well. Students seemingly held on to passive roles in the classroom, waiting for the instructor to ask questions, resisting challenging the instructor, and engaging with other students through the instructor.

and elicited a response rate of 47%. According to a summary of those evalu-ations, approximately 89% of respond-ing students agreed that explanations by the instructor were clear. Approximately 73% of the students agreed that the course materials were well prepared and carefully explained, and approximately 80% agreed that the proposed objectives of the course were consistent with those actually taught. This success was coun-tered somewhat by the fact that 77% of

Approximately 91% [of the students] agreed that

they had learned something that they considered

valuable.

experience and readiness for an inten-sive classroom experience.

It was difficult to adhere to sustained lecturing and theoretical emphasis for 3-to 4-hour time slots 3-to cover the material. On the other hand, it was also difficult to change plans once the classroom ses-sions began. Advanced preparation of the many slides was hard to move away from because some students had prepared extensively using the slides.

Students did not use the technology much for socializing or for preparation before the start of the class. There were no mandatory assignments required before or at the opening of classes to entice participation. It was observed that the same individuals made contri-butions online repeatedly and that many students chose not to contribute online. Online delivery facilitated discussion

for students with poor English-speaking skills, who tended to prefer communica-tion of their thoughts in writing rather than commenting in class. It was also very apparent that use of the technology enhanced the contributions of the female minority in the class. Rarely did the women speak out in class, yet they had a significant presence online.

Facilitating the discussion online was difficult because of the different proficiencies in English and the differ-ent terminologies used by studdiffer-ents. Furthermore, once she was back in Canada, the Canadian instructor felt “out of sorts” with the online discus-sion and worried about potential inter-ference of the student–instructor rela-tionships building in the tutorials.

Unfamiliarity with the software was stressful for the instructor. This factor

placed significant pressure on the other, Australian instructor to assist students in this area. The use of conferencing software was relatively new. Students were required to use it in many courses, but most had not received training.

Comparative Analysis of the Case Studies

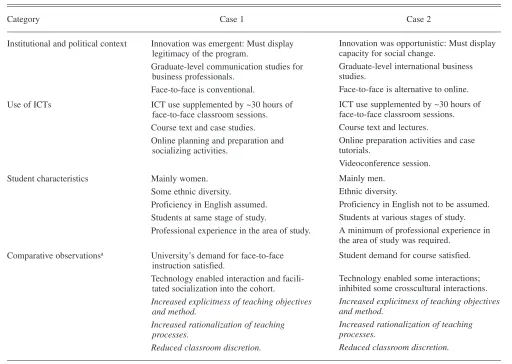

The cases that we describe in this article share the antecedent of the appli-cation of technology for the purpose of delivering courses in the intensive mode. They share the outcome of a per-ceived limitation of discretion by instructors. We argue that the applica-tion of technology in these cases is asso-ciated comparatively with this change in discretion. In Table 1, we summarize these comparative observations.

TABLE 1. Comparison of Cases by Institutional and Political Context, Use of Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs), Student Characteristics, and Comparative Observations

Category Case 1 Case 2

Institutional and political context Innovation was emergent: Must display legitimacy of the program.

Graduate-level communication studies for business professionals.

Face-to-face is conventional.

Use of ICTs ICT use supplemented by ~30 hours of face-to-face classroom sessions. Course text and case studies. Online planning and preparation and socializing activities.

Student characteristics Mainly women. Some ethnic diversity.

Proficiency in English assumed. Students at same stage of study.

Professional experience in the area of study.

Comparative observationsa University’s demand for face-to-face instruction satisfied.

Technology enabled interaction and facili-tated socialization into the cohort.

Increased explicitness of teaching objectives and method.

Increased rationalization of teaching processes.

Reduced classroom discretion.

aItalics are used to denote the common observation in the two cases.

Innovation was opportunistic: Must display capacity for social change.

Graduate-level international business studies.

Face-to-face is alternative to online.

ICT use supplemented by ~30 hours of face-to-face classroom sessions. Course text and lectures.

Online preparation activities and case tutorials.

Videoconference session.

Mainly men. Ethnic diversity.

Proficiency in English not to be assumed. Students at various stages of study. A minimum of professional experience in the area of study was required.

Student demand for course satisfied.

Technology enabled some interactions; inhibited some crosscultural interactions.

Increased explicitness of teaching objectives and method.

Increased rationalization of teaching processes.

Reduced classroom discretion.

A significant similarity between the two cases was the increased explicitness (codification) of teaching and learning activities following from the use of ICTs. The courses were substantively similar in terms of the transformational role of ICTs. Using an information systems approach to the communication occur-ring in teaching and learning, we observe that university faculty members may associate the use of technology with the reduction of information inputs brought about by the use of ICTs. The reduction of information inputs is variously referred to theoretically as preprocessing (information systems) or rationalization (sociology).

What is common to these terms is that they refer to the process of reducing opportunities for professional discretion by programming more explicitly what will be, and will not be, part of the flow of information within a particular course of study. The most salient com-mon outcome for the two cases was therefore that ICTs provided an occa-sion for recasting the profesocca-sional autonomy of the instructor.2 Using the

lens of information systems theory, we argue that ICTs required or invited the codification of the objectives and activ-ities of the course plan. As a conse-quence, information inputs were reduced, and the horizon of educational outcomes was abridged.

One factor seemed to exacerbate the negative consequences arising out of the reduced discretion in Case 2, as com-pared with Case 1. In Case 2, little opportunity was available to adapt the course on the basis of the students’ char-acteristics. There was ethnic diversity and language diversity, in that not all stu-dents had the command of the English language that the instructors expected. In addition, there were large differences among students in levels of command of prerequisite information for the course. These factors made the lack of discretion arising from preprocessing more serious in Case 2 than in Case 1. Had the course not been offered in intensive mode, which required so much preprocessing, the instructors would have prepared some early lectures to bring all the stu-dents to the same level. With preparation occurring on the weekly basis character-istic of the conventional mode, the

instructors may have been able to (a) reduce the number of slides and capital-ize on the opportunity to work with cul-tural differences in management training and understanding and (b) have students discuss implications for international business. The codification of the materi-al in advance meant that the instructors could not spend time on the opportuni-ties for learning inherent in the student characteristics and the unique context.

Furthermore, although the posting of course materials in Case 2 occurred in plenty of time for students to look at and engage in the material before the course, many students’ lack of familiarity with the technology prevented sufficient preparation. The diversity among stu-dents, in terms of the support that they needed for preparation, prevented the needed interaction around the material before the intensive course beginning. Consequently, the lack of discretion with regard to changing the content was more constraining and held more negative con-sequences in Case 2 than it did in Case 1. In terms of the common outcome, both courses displayed the transforma-tional role of technology. Technology changed the instructors’ roles decisively, because it created a need to make plan-ning and delivery decisions in advance and restricted the context for possible alterations of the plan once classes began. ICTs were therefore an occasion for codifying the objectives and activi-ties of the course plan and for trans-forming the instructor’s role. Informa-tion inputs were reduced, and the horizon of educational outcomes was abridged as part of the preprocessing task of the information flow.

The logic and method of agreement provides a useful heuristic for describ-ing the economy of information associ-ated with the alternative delivery method of intensive classroom delivery. This description establishes ICTs as a significant occasion on which the trans-formation of the instructor’s role may take place rather than as a variable to be adjusted in the teaching and learning process.

Potentials and Pitfalls

We conclude with a discussion of the potentials and pitfalls of intensive

class-room delivery and some further reflec-tion on the norm of professional auton-omy in relation to the university teacher’s role.

Potentials

1. We found that students were likely to experience the intensive classroom as a positive experience, partly owing to the maturity and determination of some of the students in this professional study program. However, we believe that a teaching mode characterized by rather close-grained planning and the selective use of instructional technology is bound to be a richer experience for students than a course without these elements. The experience will be affected by the preparation carried out by the instructor and students before the classroom ses-sions begin.

2. We found evidence of opportuni-ties to address emerging political and economic demands using intensive classroom delivery. This delivery method can be integrated with other ini-tiatives promoting innovation and the use of instructional technology in the university.

3. Some students (visible minorities, women, and other cultural or ethnic groups) may find it easier to communi-cate using computer-mediated commu-nication in the intensive classroom. This possibility should be considered in the process of course design.

4. A spirit of cohesion and common purpose can be built into a course that uses intensive classroom delivery. The key is effective use of preclassroom online and in-class activities.

Pitfalls

1. Once the course is underway, it can be difficult to make changes to the read-ings or other planned activities, because students already will have spent a great deal of effort preparing by following the Web-site plan. For example, there may be little time to ask students to add to their assigned readings or engage in further inquiry because the schedule and topics covered in the course largely will have been set before the first class begins.

2. Preparation by the instructor like-ly will be more taxing than it is in the

conventional classroom. This extra effort should be taken into account in workload planning.

3. Some student crosscultural inter-actions can be inhibited by the use of computer-mediated communication. The classroom sessions can be used as an opportunity to address and possibly remediate these inhibitions.

4. Faculty members can be expected to resist perceived reductions in profes-sional autonomy and discretion. Work-load adjustments or changes in the reward system may be appropriate.

When a faculty member does not have frequent occasions to exercise dis-cretion, there will be fewer negative consequences for intensive classroom delivery. For example, an instructor would want to have professional discre-tion to make adjustments in the follow-ing cases: when the students do not speak English well, when the students do not have a common disciplinary lan-guage for engaging with the course material (or when they do not have the necessary prerequisites), when the stu-dents do not have comparable techno-logical skills, when student maturity is lacking, when the intensive course using technology is not in the context of a pro-gram that supports or contends with intensives, when there is no social con-nection among students or there is a divisive culture, when there is a large class size (say, more than 30), and when late entries to the class are permitted.

Conclusion

The two cases described in this article have provided a window on changes now occurring in teaching and learning in higher education. Writing in a differ-ent era, Ritzer (1977, p. 61) described with some clarity the period of distur-bance now being experienced by some university faculty mambers:

Conflict within a profession may revolve around its missions, work activities, methodology and techniques, clients, col-leagues, interests and associations, recruits, and public recognition. Seg-ments form around these issues and new ones do battle with the old ones, which are seeking to maintain tradition.

The norm of autonomy that is charac-teristic of any profession is of particular

relevance in this study. By making course objectives and activities explicit through occasions for preprocessing offered by ICTs, alternative teaching methods such as intensive classroom delivery open up the “black box” of the classroom. Such occasions lead to the conversion of inputs to outputs at the point at which the inputs are made explicit. Intensive classroom delivery tends to remove information from the economy at an earlier stage than does the conventional classroom.

NOTES

1. The majority of the work for this article was completed during Dr. Rose’s time as an assistant professor with the Faculty of Extension, Universi-ty of Alberta.

2. See Barley (1986) for a discussion of the use of the term occasionin association with organiza-tional uses of technology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge Professor Aruna Deo and Dr. John Gray, the Australian colleagues who were instrumental in making this innovative delivery of the Globalization and Business Management course possible.

REFERENCES

Adria, M., & Woudstra, A. (2001). Who’s on the line? Managing student communications in dis-tance learning using a one-window approach.

Open Learning, 16(3), 249–261.

Albert, S., & Thomes, C. (2000). A new approach to computer-aided distance learning: The “automated tutor.”Open Learning, 15(2), 141–150.

Annand, D. (1999). The problem of computer-conferencing for distance-based universities.

Open Learning, 14(3), 47–52.

Arbaugh, J. (2000). Virtual classroom versus physical classroom: An exploratory study of class discussion patterns and student learning in an asynchronous Internet-based MBA course.

Journal of Management Education, 24(2),

213–233.

Barley, S. (1986). Technology as an occasion for structuring evidence from observations of CT scanners and the social order of radiology departments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31, 78–108.

Black, M. (2000). Are we all managers now?

Open Learning,15(1), 81–88.

Boshier, R., & Onn, C. (2000). Discursive con-structions of Web learning and education.

Jour-nal of Distance Education, 15(2), 1–16.

Bullen, M. (1998). Participation and critical think-ing in online university distance education.

Journal of Distance Education, 13(2), 1–32.

Clouse, R., & Nelson, H. (1999–2000). School reform, constructed learning, and educational technology. Journal of Educational Technology

Systems, 28(4), 289–303.

Giroux, H. (2002). Neoliberalism, corporate cul-ture and the promise of higher education.

Har-vard Educational Review, 425–463, 437.

Ingram, A. (1999–2000). Using Web server logs in evaluating instructional Web sites. Journal of

Educational Technology Systems, 28(2),

137–157.

Jennings, C. (1995). Organizational and manage-ment issues in telematics-based distance educa-tion. Open Learning, 10(2), 29–35.

Kennepohl, D. (2001). Using computer simula-tions to supplement teaching laboratories in chemistry for distance delivery. Journal of

Dis-tance Education, 16(2), 58–65.

Khan, B. (1997). Web-based instruction. Engle-wood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Pub-lications.

Lengwick-Hall, C., & Sanders, M. (1997). Designing effective learning systems for man-agement education: Student roles, requisite variety and practicing what we teach. Academy

of Management Journal, 40(6), 1334–1368.

Mundell, B., & Pennarola, F. (1999). Shifting par-adigms in management education: What hap-pens when we take groups seriously? Journal of

Management Education, 23(6), 663–683.

Ng, K. (2000). Costs and effectiveness of online courses and effectiveness. Open Learning,

15(3), 301–315.

Noble, D. (1995). Progress without people: New technology, unemployment, and the message of

resistance. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Noble, D. (2001). The future of the digital diplo-ma mill. Academe, 27(5), 29.

Oravec, J. (2003). Some influences of online dis-tance learning in U.S. higher education. Journal

of Further and Higher Education, 27(1),

88–103, 94.

Orlikowski, W., & Iacono, C. (2001). Research commentary: Desperately seeking the “IT” in IT research—A call to theorizing the IT arti-fact. Information Systems Research, 12(1), 121–134.

Paj, K., & Wallace, C. (2001). Barriers to the uptake of Web-based technology by university teachers. Journal of Distance Education,16(1), 70–84.

Piotrowski, C., & Vodanovich, S. (2000). Are the reported barriers to Internet-based instruction warranted? A synthesis of recent research. Edu-cation, 121(1), 48–53.

Potter, J. (1997). Support services for distance learners in three Canadian dual-mode

versi-ties: A student perspective.Unpublished

disser-tation, University of Toronto, Toronto. Ritzer, G. (1977). Working: Conflict and change.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Robson, J. (2000). Evaluating online teaching.

Open Learning, 15(2), 151–172.

Rumble, G. (1986). The planning and

manage-ment of distance education. London: Croom

Helm.

Sumner, J. (2000). Serving the system: A critical history of distance education. Open Learning, 15(3), 267–286.

Thomas, R. (2000). Evaluating the effectiveness of the Internet for the delivery of an MBA pro-gram. Innovation in Education and Training

International,97–102.

Wolcott, L. (2003). Dynamics of faculty participa-tion in distance educaparticipa-tion: Motivaparticipa-tions, incen-tives, and rewards. In Moore, M. (Ed.),

Hand-book of distance education (pp. 549–565).

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Work of faculty: Expectations, priorities, and rewards. (1994, January–February),Academe, 35–48.

Woudstra, A., & Adria, M. (2003). Organizing for the new network and virtual forms of distance education. In M. Moore (Ed.),Handbook of

dis-tance education(pp. 531–547). Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.