Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:18

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Student Reactions to Classroom Management

Technology: Learning Styles and Attitudes Toward

Moodle

Christina Chung & David Ackerman

To cite this article: Christina Chung & David Ackerman (2015) Student Reactions to Classroom Management Technology: Learning Styles and Attitudes Toward Moodle, Journal of Education for Business, 90:4, 217-223, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1019818

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1019818

Published online: 25 Mar 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 421

View related articles

Student Reactions to Classroom Management

Technology: Learning Styles and Attitudes

Toward Moodle

Christina Chung

Ramapo College of New Jersey, Mahwah, New Jersey, USA

David Ackerman

California State University, Northridge, Northridge, California, USA

The authors look at student perceptions regarding the adoption and usage of Moodle. Self-efficacy theory and the Technology Acceptance Model were applied to understand student reactions to instructor implementation of classroom management software Moodle. They also looked at how the learning styles of students impacted their reactions to Moodle. Results show that students most valued the control Moodle gave them over their educational progress. Communication was also found to be an important benefit students sought in Moodle. Individual student reaction to Moodle was influenced by visual learning and degree of laziness.

Keywords: classroom management software, learning styles, Moodle, self-efficacy, technology acceptance model

In higher education, using a course management system (CMS) has become an essential tool for many instructors. As a result researchers have started to focus on the benefits of CMS in teaching and learning. A few studies such as Chung and Ackerman (2010) and Payette and Gupta (2009) have examined managing a CMS in terms of instructors’ perceptions, but there is less investigation regarding student reaction to CMS.

In contrast to instructors, students do not have as much choice about the use of a CMS. If the course is a required course, they can choose a course section. If it is an elective, they can choose not to take the course, but for the most part selection is more likely based on time and content than on instructor use of CMS. For the most part students will expe-rience the degree of CMS that their instructors implement. Despite this lack of choice for students, CMS can influence the entire structure and flow of their coursework. More

importantly, their reaction to an instructor’s implementa-tion of CMS can greatly impact their learning experience.

The major CMS are Blackboard (Blackboard Inc., Washington, DC) WebCT (Washington, DC), and Moodle, though there are many other choices available. Despite familiarity with Blackboard or WebCT, as of August 2014, Moodle had a user-base of 53,958 registered and verified sites, serving 68,958,596 users in 7.6C million courses (Moodle, 2015). Moodle is an open-source learning man-agement system. This means Moodle is available free of charge to anybody under the terms of the General Public License—there is no licensing fee.

Moodle provides several functions. Moodle can facilitate student–instructor and student–student interactions. Mes-sage boards and customizable chat rooms allow both asyn-chronous and synchronous communication. Students themselves can communicate within groups and use discus-sion boards themselves. Study guides provided by instruc-tors and perhaps shared commonly among students are an important benefit (Lewis et al., 2005). This common ground for communication in cyberspace makes it an important tool for online classrooms. Moodle also allows for more rapid distribution of grades for exams and assignments. A

Correspondence should be addressed to David Ackerman, California State University, Northridge, College of Business and Economics, Depart-ment of Marketing, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA 91330-8377, USA. E-mail: david.s.ackerman@csun.edu

Color versions of one or more figures in this article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/vjeb.

CopyrightÓTaylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1019818

Moodle classroom home page is a very efficient tool that is a much less time consuming and error prone process than completion of the same tasks using paper or even email.

Business instructors have adopted use of the system for both online courses and face-to-face classrooms. Some have suggested that student motivation is a key factor in the success of Moodle in the classroom and that students found it easier to use (Beatty & Ulasewicz, 2006). Students do like Moodle better than faculty (Payette & Gupta, 2009), but this may be a function of greater faculty familiarity with other classroom management software.

The purpose of this study was to investigate student ceptions in adopting and using Moodle and how their per-ceptions impact the effective use of the CMS. First, this research looks at the influence of several constructs includ-ing academic self-efficacy, internet self-efficacy, usefulness, difficulty, communication effectiveness, and enjoyment on student perceptions of CMS. Second, the impact of learning styles and implicit theory on the functional benefits students derive from CMS is examined. The findings help explain student perspectives on Moodle and provide the basis for suggestions as to how faculty can effectively implement Moodle for their teaching.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION AND HYPOTHESES

Self-Efficacy and Technology Acceptance Model

From a student’s perspective, Moodle provides the means whereby they receive class materials and submit assign-ments to instructors. Studies have suggested that students do find online learning and components provided by most classroom software packages to be effective in overall learning (Clarke, Flaherty, & Mottner, 1999) and a CMS can be used in a variety of online active/passive learning experiences, including even a social dilemma game (Oertig, 2010). Overall, they are in fact very positive about most aspects of a CMS (Carvalho, Nelson, & Silva, 2011). This positive impact does not seem to vary by the learning style of the student (Young, Klemz, & Murphy, 2003).

Despite these potential benefits, the use of a CMS is not always met with optimism. Could a lack of clarity about how to use CMS, the inability to complete tasks and perhaps the stresses or other negative aspects of using it lead some students to view it with disfavor? This could also influence student evaluations of a course and their instructors.

The two theories, self-efficacy theory and Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), were utilized for a theoretical foundation in analyzing the relationships amongst these variables. Within social cognitive theory, self-efficacy the-ory was developed by Bandura (1977). Self-efficacy refers to beliefs about an individual’s capabilities to learn or per-form behaviors at designated levels (Bandura, 1986, 1997). This theory explains that an individual has a certain level of

confidence in his or her ability to perform tasks. Academic self-efficacy and Internet self-efficacy were examined as exogenous variables. Academic self-efficacy is expressing confidence in academic ability, awareness of effort toward study, and expectation for success in college attainment. Much research shows that self-efficacy influences academic motivation, learning, and achievement (Pajares, 1996; Schunk, 1995). Internet self-efficacy focuses on how well one believes s/he can accomplish needed tasks and goals on the Internet (M. L. Lai, 2008). This type of self-efficacy is a potentially important factor to examine student perceptions on Moodle.

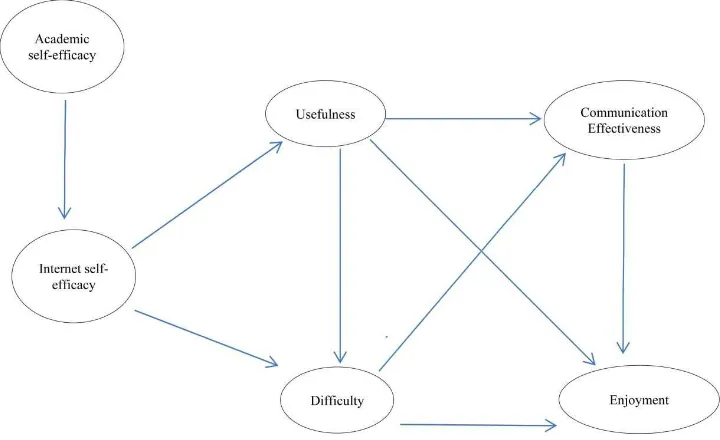

TAM was developed by Davis (1989) based on the theory of reasoned action to explain computer usage behavior. There are two constructs in the model, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), that measure the degree of an individual’s system usage and perceptions in examining behavioral intention and actual use. PU is the extent to which applications contribute to improving user performance. PEOU refers to the degree of required effort to take advan-tage of the application (Davis, 1989). Davis, Bagozzi, and Warshwa (1989) found that perceived usefulness is a major determinant of people’s intentions to use computers. Useful-ness beliefs were more salient for inexperienced users than experienced users (Taylor, 2004). Based on these theories and previous research, a research model was created (Fig-ure 1) and the following hypotheses developed to examine the relationships between the latent constructs:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Academic self-efficacy is positively related to internet self-efficacy.

H2:Internet self-efficacy is negatively related to perceived difficulty and positively related to perceived usefulness.

H3:Perceived usefulness is negatively related to perceived difficulty and positively related to communication effectiveness and enjoyment in using Moodle.

H4:Perceived difficulty is negatively related to communi-cation effectiveness and enjoyment in using Moodle.

H5: Communication effectiveness is positively related to enjoyment in using Moodle.

Learning Styles and CMS

Can learning styles impact on student reaction to classroom management systems? If so, what dimension of learning style is most closely linked to adoption of CMS such as Moodle? Students perceive that there is a relationship between general technology use and their learning style (C. Lai, Wang, & Lei, 2011). This certainly makes sense from what instructors see in the course of a semester regarding the way students communicate. Some students like to communicate online by email and some by class dis-cussion boards. Yet others prefer face-to-face communica-tion. These differences are also seen in the way work is 218 C. CHUNG AND D. ACKERMAN

turned into the instructor. If requirements about the way work are turned in is not specified, some students will pre-fer to email in assignments from a home computer, some like to post it on a classroom management site, yet others will send it in by a variety of methods from their tablet PC or cell phone as soon as they are finished. Can specific learning styles have an impact on the use of classroom man-agement technology?

Just as in face-to-face learning, students differ in how they prefer information to be presented online as well. For example, Saeed, Yang, and Sinnappan (2009) found that sensors, who are careful and more detail oriented, preferred email over other types of communication in learning where as others like intuitors and visual learners preferred blogs and videos respectively. Similarly, learning style can impact on how students utilize learning technology as well (Vigentini, 2009). Use of online material instructors supply to students is an increasingly frequently-used component of courses so it is important to determine the impact of learn-ing styles on student perceptions of the different compo-nents of a classroom management system.

In sum, not all students will react in the same way to instructor implementation of CMS. Some adapt quickly, some more slowly, and yet others really have specific needs that are fulfilled by the type of features their instructors pro-vide for them in CMS. Students who have different learning styles will take a different approach and perhaps require some flexibility on the part of the instructor. Thus, in this study, three specific questions regarding learning styles were developed.

Research Question 1 (RQ1): Do learning styles have an impact on student perceptions of classroom manage-ment technology?

RQ2: Which of the dimensions of learning styles have the greatest impact on student perceptions of classroom management technology?

RQ3:Which aspects of classroom management technology are most impacted by student learning styles?

METHOD

We administered a web survey designed to measure mar-keting student perceptions toward CMS. Data were collected using a convenience sampling method using a self-administered questionnaire among marketing major students. One hundred twenty-five respondents from six marketing classes at two universities, in the northeast and in the southwest, participated in the survey. The samples consisted of 58% women and 42% men. All respondents were between 18 and 28 years old. Eight-three percent of students were juniors and seniors. Respondents revealed that, besides Moodle, they had used Blackboard (30%), WebCT (29%), and other (16%) CMS. In addition, students indicate they have good Moodle literacy (average 5.7 of 7). For all questions, the response options consisted of a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Questionnaire items measuring Moodle usefulness (Cronbach’s a D .94), Moodle difficulty (Cronbach’s a D .86), and Internet self-efficacy (Cronbach’s aD .93) scales were adapted from Chen and Tseng’s (2012) study. Aca-demic self-efficacy scale (Cronbach’saD.85) was modified from the College Learning Effectiveness Inventory scale. Moodle communication effectiveness (Cronbach’s aD.90) and enjoyment scales (Cronbach’s a D .93) were adapted from Martınez-Torres et al.’s (2008) research. In addition, FIGURE 1 Research model: Student perceptions of Moodle.

there was a scale for implicit theory (Cronbach’s aD .83) modified from Beruchashvili, Moiso, and Heisley (2014).

Learning style scales was adapted from Fleming (n.d.). A factor analysis performed on the inventory of learning styles found four factors. These were related to being “social” (with factor loadings of .66–.81), “doesn’t like listening” (with factor loadings of .62–.83) “visual,” (with factor loadings of .72–.76), and “lazy” (with factor loadings of .57–.74).

RESULTS

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was run to assess the measurement properties of the scales. Some items with fac-tor loadings lower than .5 were deleted and a six-facfac-tor solution of 23 items was identified. The EFA solution accounted for 80% of the cumulative variance. Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure internal consistency. All meas-ures demonstrate good reliability with alpha values of .85 and greater (see Appendix).

Subsequent testing using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was examined for the overall validity of the mea-surement model. The CFA results indicate an acceptable fit withx2D358.69,dfD215,pD.000, comparative fit index (CFI) D .94, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) D .07, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) D .92. The CFI and TLI exceed the recommended cut-off value of .9 and the RMSEA is lower than the cutoff value of .08. Fur-ther, construct validity is evaluated based on the factor loading estimates, construct reliabilities, variance extracted percentages and inter-construct correlations. All loading estimates are significant (p <.000) with the lowest being .69 and the highest being .94. The variance-extracted esti-mates are .60, .82, .73, .62, 77, and .83 for academic self-efficacy, Internet self-self-efficacy, perceived usefulness, per-ceived difficulty, communication effectiveness, and enjoy-ment, respectively. In addition, the construct reliability estimates are all adequate, ranging from .85 to .98. Discriminant validity is measured by comparing the vari-ance-extracted percentage for any two constructs with the square of the correlation estimate between these two con-structs. The results indicate that the convergent validity of the model is supported and good reliability is also established.

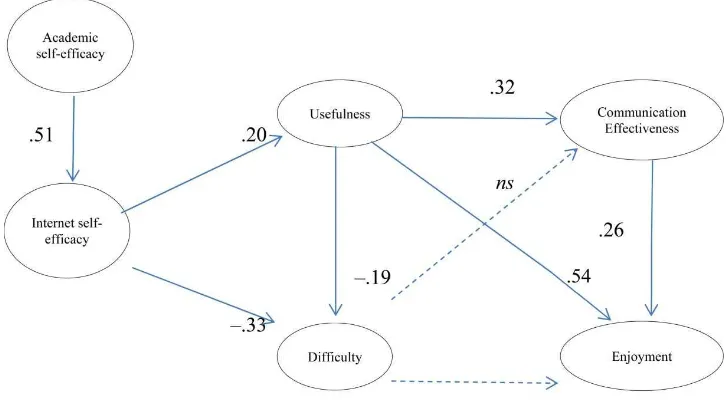

The next step was to examine the overall theoretical model specification and the hypotheses by using the struc-tural equation modeling (SEM). The SEM results indicate a satisfactory fit of data with x2 D 361.15, df D221, p D .000, CFI D .94, RMSEA D .07, TLI D .93. The SEM structural path results reveal that all hypotheses are sup-ported exceptH4(Figure 2).

To examineRQ1 throughRQ3, a regression analysis of the factors impacting on overall satisfaction with Moodle were also significant,F(7, 125)D31.31,pD.00,R2D.63.

Significant dependent variables included visual (Std.b D .12), tD2.01, dfD124, p <.05; being social (Std. b D –.14),t D –2.34, dfD 124, p < .05; difficulty (Std.b D .15),tD2.38,dfD124,p<.05; usefulness (Std.bD.25),

tD3.08,dfD124,p<.00; and control (Std.bD.48),tD 6.32,dfD124,p<.00.

In addition, a regression analysis was used to analyze student perception of the functional benefits of Moodle because classroom management software is by its nature and use functional. The results of a linear regression were significant,F(6, 125)D16.98,pD.00,R2D.44. Significant dependent variables included verbal (Std. b D .14), t D 1.97,pD.05; lazy (Std.bD–.14),tD–2.01,p<.05;

diffi-culty (Std.bD.26),tD3.82,p<.00; and communication (Std.bD.47),tD6.55,p<.00. Lastly, a correlation with the implicit theory measure found that entity theory person-ality in students was inversely related to satisfaction with Moodle (r2D–.19,pD.04).

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INSTRUCTORS

These results suggest first that the single most important factor in overall satisfaction with classroom management system is the control it gives students over their educational progress. Depending on how it is implemented by the instructor, CMS offers students flexibility in the timing and amount of work they upload at any particular time. They can also see their progress online. Such flexibility can empower students who otherwise may feel they are at the mercy of the instructor’s or department’s schedule. The implication for instructors is that they should set up CMS so that students are best able to monitor their own progress. The schedule, including assignments and readings, should be embedded as much as possible in the CMS so students know beforehand the pace of the work and how much they need to complete to move on in the course.

The result of a positive relationship between difficulty and satisfaction or functional benefits of classroom man-agement software was surprising. Perhaps, to an extent stu-dents felt that the more difficult software management was, the more effective it was. Difficulty up to a certain degree can be a challenge that is perceived as facilitating a goal. In this case, a certain degree of complexity may also have given students a sense of accomplishment that they were learning a software system. The implication of this for instructors is that it is ok to push students a little, to chal-lenge them with a CMS. Maybe instructors could set up a more elaborate and enriching curriculum on Moodle, with videos and exercises, to motivate. Learning an instructor’s system, with helpful features and functions, can be reward-ing in and of itself.

Visual learning is also an important factor in overall stu-dent satisfaction with classroom management software. 220 C. CHUNG AND D. ACKERMAN

Given the graphics and visuals in CMS such as Moodle, visual learners would be more satisfied with the system. As this trend continues with software moving over to Apple-type graphics systems, visual learners will be at an even greater advantage in coming years. The implication of this finding is that instructors need to expect to spend a little more time with students who are not visual learners when setting up a CMS. Perhaps setting up written protocols for functions in the CMS the instructor has implemented may help. Visual models for students who are not oriented toward visual learning to copy may aid in walking these students through the steps they need to complete.

On the one hand, it seems obvious that usefulness would be a factor in satisfaction with classroom management soft-ware. On the other hand, enjoyment or other positive fac-tors had no impact. This suggests that classroom management software such as Moodle are viewed strictly as tools for school work, not for fun or personal enrichment. It also means that instructors are not likely to find students available on the CMS on the weekends and breaks if they need to communicate with them and may need to use other means.

The findings for incremental versus entity theories of intelligence are in line with what would be expected given extant literature (Burnette, O’Boyle, VanEpps, Pollack, & Finkel, 2013; Shih, 2011). Those who had a more rigid entity view about their ability to deal with technology, it is fixed and cannot change, were less likely to be satisfied with Moodle. Those who had a more flexible view of ability to work with technology were more likely to be satisfied with Moodle.

Laziness impacted negatively on the functional benefits of Moodle but not overall satisfaction. This finding suggests that harder working students are more concerned

specifically with the functional benefits that can be derived from a classroom management system. They are not neces-sarily happier overall than lazier students with CMS such as Moodle. Instructors who wish to reward harder working students may emphasize the functional benefits of their implementation of the CMS. They could explain, for exam-ple, how downloading of a study guide or a group feedback discussion board can impact on a specific part of the course or the grade.

CONCLUSIONS

These results suggest that communication benefits, both communication and verbal learning style are significant, are an important perceived benefit of classroom manage-ment systems to students. Moodle does help facilitate com-munication both between student and instructor as well as between students themselves. Students may be reluctant to connect with classmates who are not friends on social media sites to do class work or group work. On the other hand, given our previous finding, classroom management software is strictly workspace. To the degree to which classroom management software can facilitate communica-tion regarding class work and events between students and instructors, it will be perceived as beneficial. Instructors can aid in this process by perhaps setting up times where out-of-class discussion can take place. Other instructors encourage and give points for student comments in chat rooms, which is an extrinsic reward that could encourage use of the CMS as a means of communication.

SEM results indicate that students who are confident in their overall academic abilities will tend to be more confi-dent in other areas such as Internet or technology usage. FIGURE 2 Tests of the hypotheses.

Overall academic self-efficacy led to Internet self-efficacy and the Internet self-efficacy is significantly related to per-ceived usefulness and perper-ceived difficulty. As shown in Figure 2, even though there is significant relationship between perceived usefulness and perceived difficulty, the only important factor that is positively related to communi-cation effectiveness and enjoyment in using Moodle is per-ceived usefulness. These results suggest that the perper-ceived usefulness of classroom management system is the key to students using it. If they feel it is useful in an overall way, they will use it to communicate with their instructors and their classmates. They will also enjoy using it, which will likely increase the time and scope of activities for the class-room management system is used. Results also suggest that the effectiveness of a CMS as a communication tool can impact on enjoyment with using, perhaps at least within the scope of the class, taking on the role of social media of choice for students.

LIMITATIONS AND FURTHER STUDY

This study used convenience samples consisting of all the students in the classes and the overall sample size was rela-tively small. Also, this study is limited in that it does not have direct measures of student use of classroom manage-ment systems. Students can say what they enjoy or what they find useful, but the relationship with behavior may be different. Future researchers should directly track class-room management system usage by students, tying behav-iors to measures of various perceptual and personality antecedents.

In addition, this study only samples traditional students who have in-class contact with the instructor and face-to-face interaction with classmates. Online students who use Moodle as their primary link to the learning experience might have different perceptions and reactions. Future researchers need to investigate student perceptions of class-room management software among online students and compare them to those of traditional students. Last, the questions regarding measuring the learning styles in the Fleming questionnaire were from a commercial website, but the items are similar to existing validated learning style inventories (Felder & Spurlin, 2005; Martinez, 2001).

REFERENCES

Ackerman, D., & Gross, B. (2007). I can start that JME manuscript next week, can’t I? The task characteristics behind why faculty procrastinate.

Journal of Marketing Education,29, 97–110.

Beatty, B., & Ulasewicz, C. (2006). Online teaching and learning in transi-tion: Faculty perspectives on moving from blackboard to the Moodle Learning Management System.TechTrends,50, 36–45.

Beruchashvili, M., Moiso, R., & Heisley, D. (2014). What are you dieting for? The role of lay theories in dieters’ goal setting.Journal of Con-sumer Behavior,13, 50–59.

Burnette, J. L, O’Boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation.Psychological Bulletin,139, 655–701.

Carvalho, A., Nelson, A., & Silva, J. (2011). Students’ perceptions of Blackboard and Moodle in a Portuguese university.British Journal of Educational Technology,42, 824–841.

Chen, H. R., & Tseng, H. F. (2012). Factors that influence acceptance of Web-based e-learning systems for the in-service education of junior high school teachers in Taiwan.Education and Program Planning,35, 398–406.

Chung, C., & Ackerman, D. (2010, April).Transitions in classroom tech-nology: Needs fulfilled by and reasons for procrastination in the imple-mentation of classroom management technology. Paper presented at the 2010 Marketing Educators’ Association, Seattle, WA.

Clarke, I. III, Flaherty, T. B., & Mottner, S. (1999). Student percep-tions of educational technology tools.Journal of Marketing Educa-tion,2, 69–77.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology.MIS Quarterly,18, 319–340. Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshwa, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of

computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manage-ment Science, 35, 982–1003.

Felder, M. F., & Spurlin, J. (2005). Applications, reliability and validity of the index of learning styles.International Journal of Engineering Edu-cation,21, 103–112.

Fleming, G. (n.d.).Learning styles: Know and use your personal learning style. Retrieved from http://homeworktips.about.com/od/homewor khelp/a/learningstyle.htm

Lai, C., Wang, Q., & Lei, J. (2012). What factors predict undergraduate students’ use of technology for learning? A case from Hong Kong. Com-puters and Education,59, 569–579.

Lai, M. L. (2008). Technology readiness, Internet self-efficacy and com-puting experience of professional accounting students.Campus-Wide Information Systems,25, 18–29.

Lewis, B. A., MacEntee, V. M., DeLaCruz, S., Englander, C., Jeffrey, T., Takach, E., & Woodall, J. (2005). Learning management systems com-parison.Proceedings of the 2005 Informing Science and IT Education Joint Conference, 17–29.

Lincoln, D. (2001). Marketing educator Internet adoption in 1998 versus 2000: Significant progress and remaining obstacles.Journal of Market-ing Education,23, 103–116.

Martinez, A. (2001). Mass customization: designing for successful learn-ing.International Journal of Educational Technology,2(2). Retrieved from http://www.ed.uiuc.edu/ijet/v2n2/martinez/index.html

Martınez-Torres, M. R., Toral Marın, S. L., Barrero Garcıa, F, Gallardo Vazquez, S., Arias, M., & Torres, T. (2008). A technological acceptance of e-learning tools used in practical and laboratory teaching, according to the European higher education area.Behaviour & Information Tech-nology,27, 495–505.

Moodle. (2015).Moodle statistics. Retrieved from https://moodle.net/stats/ Oertig, M. (2011). Debriefing in Moodle: Written feedback on trust and knowledge sharing in a social dilemma game.Simulation and Gaming,

41, 374–389.

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings.Review of Educational Research,66, 543–578.

Payette, D. L., & Gupta, R. (2009). Transitioning from Blackboard to Moo-dle course management software: Faculty and student opinions. Ameri-can Journal of Business Education,2(9), 67–73.

Saeed, N., Yang, Y., & Sinnappan, S. (2009). Emerging web technologies in higher education: A case of incorporating blogs, podcasts and social book-marks in a Web programming course based on students’ learning styles and technology preferences.Educational Technology & Society,12, 98–109.

222 C. CHUNG AND D. ACKERMAN

Schunk, D. H. (1995). Self-efficacy, motivation, and performance.Journal of Applied Sport Psychology,7, 112–137.

Shih, S. (2011). Perfectionism, implicit theories of intelligence, and Taiwa-nese eight-grade students’ academic engagement. Journal of Educa-tional Research,104, 131–142.

Taylor, W. A. (2004). Computer-mediated knowledge sharing and individ-ual user differences: An exploratory study.European Journal of Infor-mation Systems,13, 52–64.

Vigentini, L. (2009). Using learning technology in university courses: Do styles matter? Multicultural Education & Technology Journal,

3, 17–32.

Young, M. R., Klemz, B. R., & Murphy, J. W. (2003). Enhancing learning outcomes: The effects of instructional technology, learning styles, instructional methods and student behavior.Journal of Marketing Edu-cation,25, 130–142.

APPENDIX MEASURES

Implicit Theory

1. A person’s ability to work well with the internet and soft-ware is something very basic to them and can’t be changed much.

2. Whether a person can work well with the internet and soft-ware is deeply ingrained in their personality. It cannot be changed much.

3. There is not much that can be done to change whether or not a person can work well with the internet and software.

Internet Self-Efficacy

1. I am confident that I can connect to the web pages I want to browse.

2. I am confident that I can use the Internet to download the information I need.

3. I am confident that I can use the search for information.

Academic Self-Efficacy

1. I have high academic expectations of myself. 2. I believe it is possible for me to make good grades. 3. I am determined to do what it will take in order to succeed with my goals.

4. Gaining knowledge is important to me.

Difficulty

1. I often become confused when I use Moodle. 2. I make errors frequently when using Moodle. 3. Interacting with Moodle is often frustrating.

Usefulness

1. Using Moodle reduces time spent on unproductive activities in my learning.

2. Using Moodle enhances my effectiveness on my study. 3. Using Moodle improves the quality of the study I do. 4. Using Moodle makes it easier to do my study. 5. Using Moodle is an effective way for me to learn.

6. Moodle is an appropriate tool for me to use as a learning medium.

Moodle—Communication Effectiveness

1. Moodle makes discussion with classmates easier.

2. Moodle makes it easier to share new knowledge with classmates.

3. Moodle makes it easier to get access to classmates’ opinions.

Moodle—Functional Effectiveness

1. Moodle helps me organize my time so that I have plenty of time to study.

2. Moodle helps me make study goals and keep up with them. 3. Moodle helps me break big assignments into manageable pieces.

4. Moodle helps me the ways to organize course materials. 5. Moodle helps me in better understanding of the project/ assignment.

6. Moodle helps me to accomplish my task quickly. 7. Moodle helps me to improve my performance.

8. Moodle helps me to enhance effectiveness of my assign-ment/project.

Satisfaction

1. I am satisfied with Moodle. 2. I am pleased with Moodle.

3. I am satisfied by the contents of the information found on Moodle.

4. I am satisfied by the format in which information is found on Moodle.

5. I am satisfied by the timeliness in which information is found on Moodle.

Enjoyment

1. Using Moodle is a fun activity.

2. Using Moodle stimulates my imagination. 3. Using Moodle is interesting.

Learning Style

1. I like to read out loud. 2. I like oral reports. 3. I am good at explaining. 4. I enjoy acting / being on stage. 5. I am good in study groups. 6. I like science lab.

7. I study with loud music on. 8. I like adventure books and movies. 9. I usually take breaks when studying. 10. I am nervous during lectures. 11. I need quiet study time.

12. I have to think awhile before understanding lecture. 13. I am good at spelling

14. I understands/likes charts. 15. I am good with sign language.